Allow me to begin my review of Rabbi Prof. Daniel Sperber’s new volume

Darka shel Halakha, with a few words of introduction.[1] I have the greatest respect for Prof. Sperber both as a scholar par excellence and as a human being. Over the almost 35 years I have been at Bar-Ilan University, we have developed a warm friendship and mutual respect. He writes clearly and beautifully, with great knowledge, sensitivity and depth – and his book

Darka shel Halakha is no exception. Nevertheless, I am forced to disagree with his analysis and conclusions. I strongly believe that we have to be sensitive to women’s spiritual needs or as Hazal say: לעשות נחת רוח לנשים (Sifra, Parsheta 2; Hagiga 16b). But at the same time, we have to be honest about what the halakha clearly states – so that, at the same time, we will not be guilty of האהבה מקלקלת את השורה.

The question of women receiving aliyyot, which lies at the center of Darka shel Halakha, is briefly discussed in a baraita cited in the Talmud Megilla (23a) which reads (Source 1):

(1) תלמוד בבלי מסכת מגילה דף כג עמוד א

תנו רבנן: הכל עולין למנין שבעה, ואפילו קטן ואפילו אשה. אבל אמרו חכמים: אשה לא תקרא בתורה, מפני כבוד צבור.

Despite the above negative ruling of the Talmud and, in its wake, of all subsequent codifiers,[2] within the last decade, there have been two major attempts to reopen this issue. One was penned by R. Mendel Shapiro[3] who argues that kevod ha-tsibbur is a social concept – and a woman’s general standing in society was lower than men’s. Nowadays when this is no longer true, a community can be mohel on its kavod – voluntarily set aside its honor. He errs, however, since the vast majority of rishonim and aharonim disagree with his analysis. Kevod ha-tsibbur has nothing to do with social standing. The vast majority of posekim maintain that kevod ha-tsibbur stems from women’s lack of obligation in keri’at haTorah, and expresses itself either in terms of tsniut or zilzul ha-mitsvah. The Tsniut School argues that women should not be at the center of communal ritual unnecessarily – and this is particularly true by keri’at haTorah, from which they are freed. The second school maintains that there is an issue of zilzul ha-mitsva in that the men who are duty-bound should fulfill the mitsva that is incumbent upon them – and not delegate it to those who are not obligated.[4]

The second attempt is that of R. Prof. Daniel Sperber,[5] in Darka shel Halakha, and I would like to focus on two major issues.

Kevod haTsibbur: Instruction or Recommendation?

Firstly, R. Sperber has suggested that the phrase in Megilla 23a “However, the Rabbis declared: a woman should not read from the Torah – because of kevod ha-tsibbur” describes what Hazal believed to be the preferred or recommended mode of conduct, the ideal way of performing keri’at haTorah.

Indeed, ke-darko ba-kodesh, Prof. Sperber surveys all the places where it states אבל אמרו חכמים and shows that some cases are merely expressions of the ideal, while others refer to things that are actually assur. Yet, he concludes [Note 19, p. 21] that that in the case of women’s aliyyot: “לא נראה שמדובר … בתקנת חז”ל אלא שאינו ראוי”

This position is very problematic, particularly in this case of women’s aliyyot which is one of kevod ha-tsibbur.

(1) Firstly, Meiri, Kiryat Sefer, Ma’amar 5, sec. a, writes (Source 2):

(2) מאירי, קרית ספר, מאמר חמישי חלק א

נמצאת למד …שהכל עולין למנין ז’ אפילו אשה וקטן…, אלא שמיחו באשה מפני כבוד צבור…

The word “מיחו” appears many times in the Mishnaic and Tamudic literature and it refers to strongly verbalized objection and public reproof. See for example, Source 3.

(3) מסכת פסחים פרק ד משנה ח

משנה: ששה דברים עשו אנשי יריחו על שלשה מיחו בידם ועל שלשה לא מיחו בידם

רמב”ם: אלו הששה דברים כולם היו שלא ברצון חכמים, אלא שעל שלשה מהם – והם הראשונים – לא מיחו בידם חכמים, ושלשה המנויים באחרונה מיחו בידם.

Clearly, from the Meiri’s perspective, the statement אבל אמרו חכמים by women’s aliyyot is not a simple recommendation.

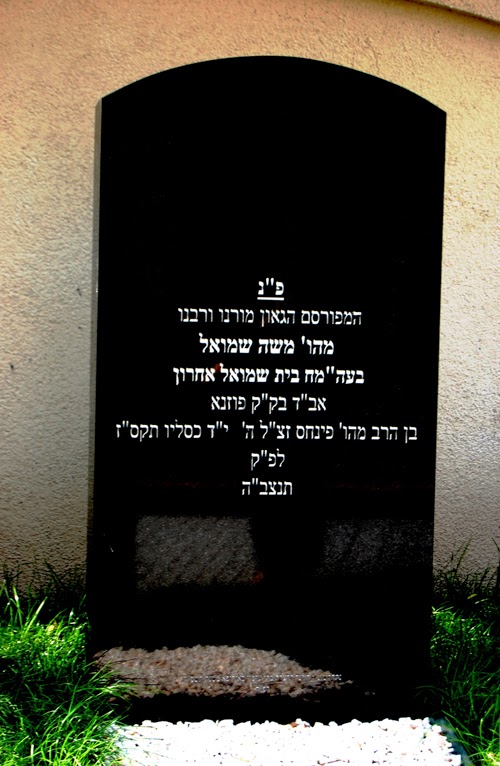

(2) Secondly, there is a group of rishonim and aharonim who maintain that in the specific case of women’s aliyyot, women cannot receive aliyyot, even in cases of she’at ha-dehak or be-diavad. This school includes the Rambam and Semag and many subsequent aharonim (R. Abraham Pinso; R. Matsli’ah Mazuz; R. Ben-Zion Lichtman, R. Zalman Nehemiah Goldberg and R. Isaac Zilberstein). For example, Rambam (Sources 4 and 5) writes without any qualification that women may not receive aliyyot:

(4) רמב”ם הלכות תפילה ונשיאת כפים פרק יב, הלכה יז

אשה לא תקרא בציבור מפני כבוד הציבור…

(5) הרב מסעוד חי רוקח, מעשה רוקח שם

ורבינו כתב קיצור הדין ד-“אשה לא תקרא מפני כבוד הציבור”, א”כ נאסר לגמרי…

Semag (Source 6) records that minors may receive aliyyot, but makes no mention of women whatsoever. On the contrary, he maintains (Sources 7 and 8) that women cannot motsi men in megilla, even be-di-avad, just as they can’t receive aliyyot.

(6) הרב משה בן יעקב מקוצי, ספר מצוות גדול (סמ”ג), עשין סימן יט

כמה [הם] הקוראים, בשבת בשחרית שבעה .. וקטן היודע לקרות ויודע למי מברכים עולה בשבעה למניין.

(7) ספר מצוות גדול – מצוות מדרבנן, הלכות מגילה

…דאף על גב דנשים חייבות במקרא מגילה אינן מוציאות את הזכרים. ואל תשיבני נר חנוכה דאמרינן בפרק במה מדליקין (שבת כג, א) דאשה מדלקת משמע אף להוציא האיש. דשאני מקרא מגילה שהוא כמו קריאת התורה לכך אינה מוציאה את האיש.

(8) מגן אברהם סימן תרפט ס”ק ה

“וי”א שהנשים אינם מוציאות את האנשים “

אינם מוציאות – ול”ד לנרות חנוכה דשאני מגילה דהוי כמו קריאת התורה (סמ”ג) פי’ ופסולה מפני כבוד הצבור ולכן אפי’ ליחיד אין מוציאה דלא פלוג (רא”ם)

Clearly, according to these authorities, the statement אבל אמרו חכמים is not a simple recommendation.

(3) There is another very large group of posekim (perhaps the majority) led by the R. Yoel Sirkis (Ba”h; Sources 9 and 10) who maintain that one cannot be mohel on kevod ha-tsibbur – particularly in the case of women’s aliyyot. However, bi-she’at ha-dehak – where there is no alternative or no one else eligible – a woman can read, lest keri’at haTorah be cancelled. It is to such cases that the Gemara in Megilla was referring.

(9) הרב יואל סירקיס, בית חדש (ב”ח) טור או”ח סימן נ”ג ד”ה “ואין ממנין”

…אלא הדבר פשוט, כיון שכך תקנו חכמים דחששו לכבוד ציבור, אין ביד הציבור למחול.

(10) בית חדש, טור אורח חיים סימן קמ”ד

… מה שתיקנו חכמים .. משום כבוד הציבור לא תקנו מתחילה אלא היכא שאפשר

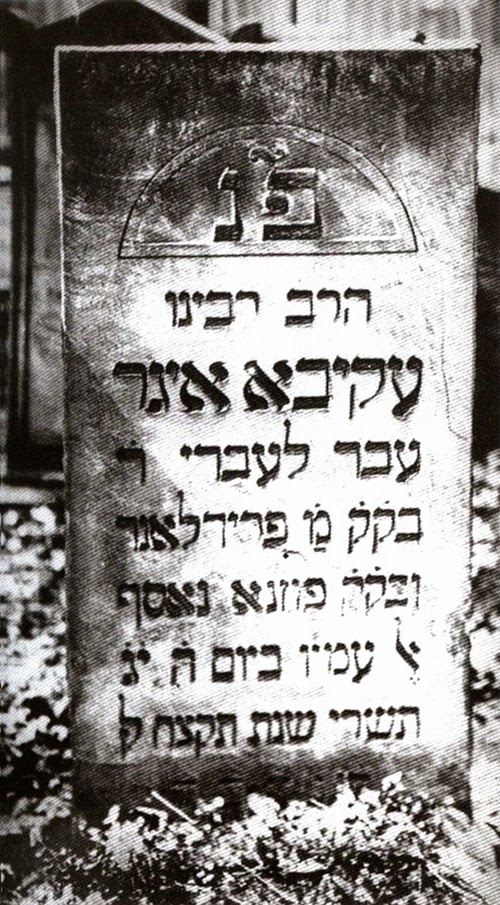

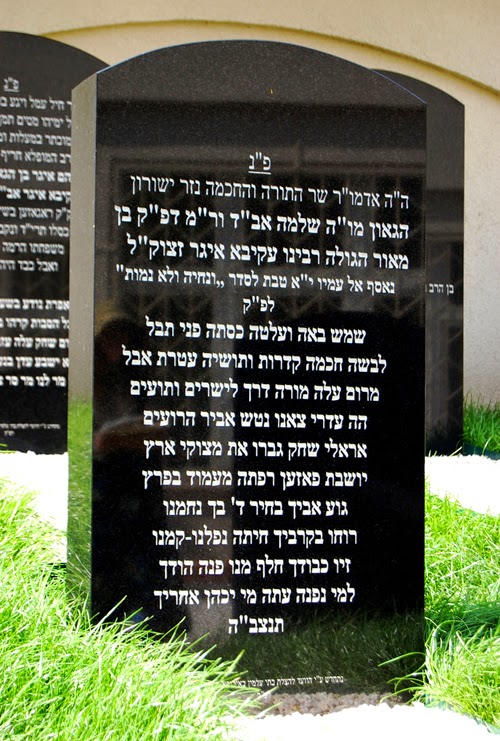

For example, in a case of a city with only kohanim cited by Rabbi Sperber himself, Maharam mi-Rothenburg (Source 11) permits women to receive the third through seventh aliya. Otherwise the Torah reading would not occur, for the lineage of the kohanim would be challenged were they to receive the remaining aliyyot. In the language of the Maharam:

(11) שו”ת מהר”ם מרוטנברג חלק ד (דפוס פראג) סימן קח

…ועיר שכולה כהנים ואין בה [אפי’] ישראל אחד נראה לי דכהן קורא פעמיים ושוב יקראו נשים דהכל משלימי’ למנין ז’ אפי’ עבד ושפחה וקטן (מגילה כ”ג ע”א). ונהי דמסיק עלה אבל אמרו חכמי’ לא תקרא אשה בתורה מפני כבוד הצבור, היכא דלא אפשר ידחה כבוד הצבור מפני פגם כהנים הקוראים שלא יאמרו בני גרושות.

Maharam mi-Rothenburg was only willing to permit bi-she’at ha-dehak. This certainly doesn’t sound like a recommendation המלצה. Rather it is permission given only bi-she’at ha-dehak.

It would seem to me that in Darka shel Halakha there is a blurring of the difference between le-khathila and be-di-avad. For example, Hazal say that one should not use a milchig spoon שאינו בן יומו (not used in last 24 hours) to stir hot chicken soup. Similarly, Hazal indicate that one shouldn’t eat out of utensils that haven’t been immersed in a mikva. In both cases, be-di-avad, the food remains perfectly kosher. Hazal’s ruling in both these cases is not a recommendation – but rather a clear directive how one is required to act; under normative conditions, it is assur to act otherwise. This is also true regarding women’s aliyyot – Hazal forbade it le-khathila, even though be-di-avad or bi-she’at ha-dehak the aliyya may be valid.

Now it should be appreciated that from Prof. Sperber’s perspective it is important that אבל אמרו חכמים be only a המלצה. Prof. Sperber wants to maintain that there really is no “down side” to women getting aliyyot. However, to my mind, he errs – kevod ha-tsibbur is a takana le-khathila, not a recommendation.

In this regard, I would also like to briefly mention one further crucial point, relevant to both the papers of R. Mendel Shapiro and R. Daniel Sperber – but which we will not be able to develop fully here at the Seforim blog.[6] When Hazal talked about women getting aliyyot, they were referring to a system in which the oleh made the berakhot and read aloud – for himself and the community. However, nowadays, the job of the oleh is bifurcated: the oleh makes the berakhot and ba’al korei reads aloud. This raises a fundamental question: how can one person make berakhot, while another does the ma’aseh ha-mitsva. For there not to be a berakha le-vatalah there must be a mechanism to transfer the reading from the ba’al korei to the oleh. That mechanism is either shom’eah ke-oneh or shelihut. But both mechanisms require that both the oleh and ba’al korei be obligated – otherwise there is no areivut. Since women are not obligated in keri’at haTorah, they can serve neither as the oleh nor as the ba’al korei – me-ikkar ha-din – because the birkhot haTorah of the oleh will be berakhot levatalah. Note that all this has nothing to do with kevod haTsibbur. The only case in which the issue of kevod haTsibbur begins is in the uncommon case where a woman makes the berakhot and reads for herself.[7] Hence, under a bifurcated system, there is a clear downside in allowing women to read or serve as olot – a proliferation of berakhot le-vatala!

Does Kevod haBeriyyot Defer Kevod haTsibbur –

The Rules of Kevod haBeriyyot

Lets now turn to the second issue – and this is Prof. Sperber’s major hiddush in this book. Briefly, Prof. Sperber notes that there is a concept in halakha called kevod ha-beriyyot which refers to shame or embarrassment (בושה או בזיון) which would result from the fulfillment of a religious obligation. The view of the halakha is that kevod ha-beriyyot can defer rabbinic obligations and prohibitions. Hence, Prof. Sperber maintains that if there is a community of women who are offended by their not receiving aliyyot – because of the rabbinic rule of kevod hatsibbur, then kevod ha-beriyyot should defer kevod ha-tsibbur.

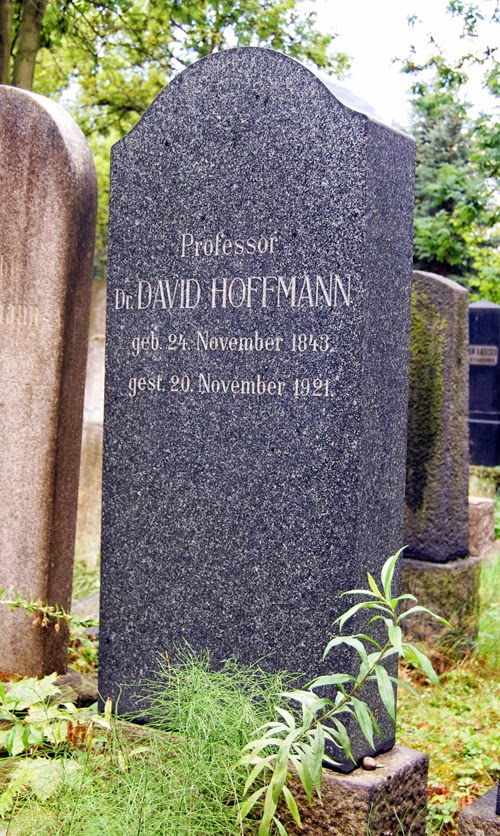

Professor Sperber’s book is devoted to describing the use of kevod ha-beriyyot in the halakhic literature. He is by no means the first to do this and the subject is extensively reviewed and analyzed by Rabbis Rakover,[8] Blidstein,[9] Lichtenstein,[10] Feldman,[11] and many others.[12]

Let’s begin with the Gemara in Berakhot 19b:

(12) תלמוד בבלי מסכת ברכות דף יט עמוד ב

(א) אמר רב יהודה אמר רב: המוצא כלאים בבגדו פושטן אפילו בשוק, מאי טעמא (משלי כ”א) “אין חכמה ואין תבונה ואין עצה לנגד ה'” – כל מקום שיש חלול השם אין חולקין כבוד לרב.

(ב) מתיבי: קברו את המת וחזרו, ולפניהם שתי דרכים, אחת טהורה ואחת טמאה, בא בטהורה – באין עמו בטהורה, בא בטמאה – באין עמו בטמאה, משום כבודו. [רוב הראשונים גורסים: באים בטמאה, בא עמהם משום כבודם] אמאי? לימא: אין חכמה ואין תבונה לנגד ה’. תרגמה רבי אבא בבית הפרס דרבנן

(ג)…תא שמע: גדול כבוד הבריות שדוחה [את] לא תעשה שבתורה. ואמאי? לימא: אין חכמה ואין תבונה ואין עצה לנגד ה’! – תרגמה רב בר שבא קמיה דרב כהנא בלאו (דברים י”ז, יא) דלא תסור [מן הדבר אשר יגידו לך ימין ושמאל[ …כל מילי דרבנן אסמכינהו על לאו דלא תסור, ומשום כבודו שרו רבנן.

(ד) רש”י: כל מילי דרבנן וכו’ – והכי קאמר להו: דבר שהוא מדברי סופרים נדחה מפני כבוד הבריות, וקרי ליה לא תעשה – משום דכתיב לא תסור, ודקא קשיא לכו דאורייתא הוא, רבנן אחלוה ליקרייהו לעבור על דבריהם היכא דאיכא כבוד הבריות.

The upshot of this Gemara is that if one is wearing sha’atnez – the wearer is obligated to remove it even in the marketplace, despite any possible embarrassment. The Gemara explains that G-d’s honor/dignity takes priority over that of Man. However, if the garment is only rabbinically forbidden, one can wait until they return home to change. The reason is that kevod ha-beriyyot, the honor of the individual, can defer rabbinic prohibitions.

Prof. Sperber adequately shows that kevod ha-beriyyot has always been an important consideration in pesak. However, an in-depth survey of the responsa literature over the past 1000 years makes it clear that it cannot be invoked indiscriminately. Indeed, as the gedolei ha-posekim make apparent, there are clearly defined parameters which Prof. Sperber seems to ignore. Hence, R. Sperber’s application of kevod ha-beriyyot to the issue of women’s aliyyot is seriously flawed. In this brief presentation, we will discuss nine of the aforementioned principles.

(1) Firstly, kevod ha-tsibbur is merely the kevod ha-beriyyot of the tsibbur.[13] Hence it makes no sense that the honor of the individual should have priority over the honor of a large collection of individuals. Indeed, this is explicitly stated by the 13th century Meiri. [Source 13; Meiri is referring to Source 12ב]

(13) מאירי, בית הבחירה, ברכות דף יט עמוד ב:

{יש גורסים בא בטומאה באין עמו. ואין הדברים נראין} שאין כבוד רבים נדחה מפני יחיד או יחידים, [וכן הוא] באבל רבתי…ואף בתלמוד המערב…

(2) Secondly, The Meiri (Source 14) also emphatically states:

(14) מאירי, בית הבחירה, ברכות דף יט עמוד ב:

…שלא אמרה תורה כבד אחרים בקלון עצמך…

Giving women aliyyot by overriding kevod ha-tsibbur with kevod ha-beriyyot would effectively be honoring women by dishonoring the community – and, hence, cannot be done.

(3) R. Sperber’s suggestion would ask us to uproot completely the rabbinic ban on women’s aliyyot. However, kevod ha-beriyyot can only temporarily set aside a rabbinic ordinance. As stated in the Jerusalem Talmud (Source 15):

(15) תלמוד ירושלמי כלאים פ”ט ה”א, לב ע”א

הרי שהיה מהלך בשוק ונמצא לבוש כלאים, תרין אמוראין (שני אמוראים חולקים בדבר): חד אמר אסור; וחרנה (ואחר) אמר מותר. מאן דאמר אסור – דבר תורה; מאן דאמר מותר – כההיא דאמר רבי זעירא: גדול כבוד הרבים שהוא דוחה את המצוה בלא תעשה שעה אחת.

Many of the commentaries on the Yerushlami and posekim hold that this proviso of sha’ah ahat applies to Rabbinic mitsvot as well – including: Tosafot, Ketubot 103b, end of s.v. “Oto”; Or Zarua, Hilkhot Erev Shabbat, sec. 6; Penei Moshe; Vilna Gaon; R. David Pardo; Arukh haShulhan (Source 16); and others.

(16) ערוך השולחן, יו”ד סימן ש”ג, סעיף ב:

שאני הכא [בכלאים] דהוא לשעה קלה, דכשיבא לביתו יגידו לו ויפשוט. ..ואפי’ באיסור דרבנן תמידי נ”ל דמחוייב להגיד לו, ואין למנוע מצד כבוד הבריות

(4) Next, many posekim including R. Yair Hayyim Bachrach, R. Meir Simha of Dvinsk (Source 17), R. Jeroham Perlow, R. Moses Feinstein, R. Chaim Zev Reines indicate that the “dishonor” that is engendered must result from an act of disgrace – not from refraining to give honor. As Rabbi Meir Simcha of Dvinsk writes:

(17) אור שמח (הרב מאיר שמחה הכהן מדווינסק) הלכות יו”ט פרק ו, הלכה י”ד

גדול כבוד הבריות…זה דווקא במידי דבזיונא הוא לבריות, אבל…ענין של כבוד…מי שרי?

Only in cases where kavod is obligatory (e.g., for a King or mourner) is the absence of kavod considered embarrassing, as indicated by R. Isaac Blazer (Source 18),

(18) שו”ת פרי יצחק, נד (הרב יצחק בלזר)

צריך לומר דסבירא להו לגמרא במקום שהכבוד מחוייב גם העדר כבוד הוא בכלל כבוד הבריות, דהעדר כבוד הוא כמו גנאי… ועיין בכתובות (דף סט) מניין שאבל יושב בראש….

Prof. Yaakov Blidstein discusses burial on Yom Tov sheini shel galuyot, which is permitted because Yom Tov sheni is de-rabbanan, while not burying is kevod ha-beriyyot.[14] However, a long list of posekim will not permit 20 individuals to violate Yom Tov sheni to attend to a burial, when only 10 are required to bury the deceased and the additional 10 would be coming along out of honor. Only the first 10 are permitted.

Similarly, in the case of aliyyot, no act of shame has been performed to all those not called to the Torah (both men and women); they are simply not honored. Kevod ha-beriyyot cannot be activated under such conditions.

R. Daniel Sperber in his book Darka shel Halakha (p. 77, note 104) attempts to challenge this principle – that kevod ha-beriyyot is inapplicable when no act of shame has been performed. He cites the fact that a bride is permitted to wash her face on Yom Kippur (Source 19).

(19) מסכת יומא פרק ח משנה א

משנה: יום הכפורים אסור באכילה ובשתיה וברחיצה ובסיכה ובנעילת הסנדל ובתשמיש המטה והמלך והכלה ירחצו את פניהם והחיה תנעול את הסנדל דברי רבי אליעזר וחכמים אוסרין:

רשי והכלה – צריכה נוי עד שתחבב על בעלה, וכל שלשים יום לחופתה היא קרויה כלה.

ר’ עובדיה מברטנורא: והכלה – צריכה נוי כדי לחבבה על בעלה. וכל שלשים יום קרויה כלה:

R. Sperber assumes that the prohibition against washing on Yom Kippur is rabbinic (when many authorities hold it is biblical) and that the permission to wash stems from kevod ha-beriyyot. Based on this, he wants to demonstrate that the shame here results from something that was not done.

This analysis is in error because the leniency for a bride has nothing to do with kevod ha-beriyyot. What was forbidden was rehitsa shel ta’anug, but not washing of necessity, e.g., for cleanliness. A bride is permitted to wash her face on Yom Kippur, so that her face would not be displeasing in her new grooms eyes – and this is considered laving of necessity. As Rashi and Rav write (Source 19 above), a bride requires beauty.

R. Sperber (p. 83) further cites a responsum of R. Isaiah of Trani, Resp. haRid, sec. 21 which permits the lighting of candles in the synagogue on Yom Tov because of “kevod ha-beriyyot.” R. Sperber attempts to use this example to demonstrate that kevod ha-beriyyot can set aside prohibitions even if it is only to honor those who are attending synagogue.

Unfortunately, he errs in his analysis here as well. Similar teshuvot are found from the Rid, Rosh and Maharam of Rothenburg.[15] And their goal is to show that lighting candles in the synagogue come under the rubric of tsorekh okhel nefesh because they honor people (Rid), the synagogue (Maharam) or the holiday (Rosh). Once it its tsorekh okhel nefesh, it is the tsorekh okhel nefesh which defers the prohibition.

(5) Nearly all authorities – including, inter alia, R. Naftali Amsterdam (Source 20), R. Elhanan Bunim Wasserman, R. Makiel Tsvi haLevi Tannenbaum, Rav Yitzchak Nissim (Source 21), R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik, R. Elijah Bakshi Doron (Source 22), R. Israel Shepansky – maintain that kevod ha-beriyyot requires an objective standard that affects or is appreciated by all.

(20) שו”ת פרי יצחק, נג

הרב נפתלי אמשטרדם: כי הנה כבוד הבריות לא נאמר רק על דבר שהוא גנאי לכל מין האנושי יהיה מאיזה מין שיהיה, כמו מת מצוה או לילך ערום שרוב בני האדם מתביישים מזה. אבל בדבר שהבזיון מתייחס רק לאדם הזה לפי תכונתו, כמו לישא שק או קופה, בזה לא שייך כלל לפטור מטעם כבוד הבריות.

(21) הרב יצחק ניסים, תשובה כתב יד, מרחשון תשכ”ד (יד הרב ניסים)

וכמובן שתלך [הבת מצווה] לפני כן לבית הכנסת להתפלל, אבל לא לעלות לתורה. הלכה מפורשת היא שאין אשה קוראת בתורה בציבור, ואין משנים את ההלכה לפי הרגשות של בני אדם.

(22) הרב אליהו בקשי דורון, שו”ת בנין אב, ח”ב, סימן נ”ה, אות ג’

…כבוד האבל דין הוא שיש לכבד כל האבלים, ובכגון זה כבוד הבריות שיכבדו האבל… אבל אדם פרטי שמחליט לכבד את עצמו…כבודו משיקולים פרטיים אינו יכול לפטור אותו, או לדחות איסור דרבנן.

This view explicitly rejects subjective standards – in which what is embarrassing results from the idiosyncrasies or hypersensitivities of an individual or small group. The vast majority of religiously committed women are not offended when they do not receive an aliyya. Indeed, they understand and accept the halakhic given, although some might clearly have preferred it to be otherwise.

More importantly, does it make halakhic sense that if a group of women – nay, any group, says: “this Rabbinic halakha offends me” – be it mehitsa, tsni’ut, kashrut, stam yeynam, many aspects of taharat ha-mishpahah, who counts for a minyan, and who can serve as a hazzan – then we should have a carte blanche to go about abrogating it. Such a position is untenable, if not unthinkable.[16]

(6) Many leading scholars[17] emphasize that, as in the cases of kevod ha-beriyyot discussed in Berakhot 19b and elsewhere, the shame must result from extraneous factors. Thus, removing the kilayyim garment per se’ is not what causes the shame. Rather, it is that one has no other garment underneath and, hence, remains naked. In such cases, kevod ha-beriyyot can be invoked to nullify the rabbinic commandment which leads to the dishonor. However, kevod ha-beroyyot cannot be invoked to nullify a rabbinic commandment, where the shame comes from the very fulfillment of the rabbinic injunction itself.

Take for example one who is invited to dine with his colleagues or clients, would we allow him to avoid embarrassment by eating fruit and vegetables from which terumot and ma’asrot (which nowadays is Rabbinic) have not been removed, or by consuming hamets she-avar alav haPesah, or by drinking stam yeynam (wine touched or poured by a non-Jew). Or alternatively, suppose someone is at a meeting and is ashamed to walk out in order to daven Minha. And what about prayers at the airport in between flights. Would we allow him to forgo his rabbinic prayer obligation because of this embarrassment?

The answer is that in those cases where acting according to halakha – be it to not eat terumot and ma’asrot, or to not drink stam yeynam, or to fulfill ones prayer obligation – creates the embarrassment, then kevod ha-beriyyot cannot set aside the Rabbinic prohibition. One should be proud to be fulfilling the halakha. Similarly, kevod ha-beriyyot cannot be invoked to uproot the rabbinic consideration of kevod ha-tsibbur which prevents women’s aliyyot. This is because the dishonor stems directly from the very fact that women are not given aliyyot in accordance with the rabbinic guidelines.

(7) That the rabbis of the Talmud were sensitive to women’s spiritual needs is evident from the rabbinic concept of nahat ru’ah (spiritual satisfaction), which was invoked in a variety of instances to permit certain special dispensations for women.[18] R. Sperber maintains that this concept is an expression of kevod ha-beriyyot.[19] Yet, despite this admitted sensitivity, Hazal themselves were not concerned about kevod ha-beriyyot when they ruled that, because of kevod ha-tsibbur, women should not le-khathila receive aliyyot. Hence, how can we?

This argument is all the more true according to the explanation of Rashi on the mechanism of kevod ha-beriyyot deferments. Rashi (Source 12ד cited above) explains that in instances of kevod ha-beriyyot the Rabbis “forgo their honor to allow their edict to be violated.”

(12) תלמוד בבלי מסכת ברכות דף יט עמוד ב

….. כל מילי דרבנן אסמכינהו על לאו דלא תסור, ומשום כבודו שרו רבנן.

(ד) רש”י כל מילי דרבנן וכו’ – והכי קאמר להו: דבר שהוא מדברי סופרים נדחה מפני כבוד הבריות, וקרי ליה לא תעשה – משום דכתיב לא תסור, ודקא קשיא לכו דאורייתא הוא, רבנן אחלוה ליקרייהו לעבור על דבריהם היכא דאיכא כבוד הבריות.

It is one thing if the clash is unexpected, unanticipated and accidental. But in the case of keri’at haTorah, it was Hazal themselves who knowingly set up the rule of kevod ha-tsibbur which precludes women from aliyyot. Why would we expect them to forgo their honor in such a case?

(8) The Rivash (Resp. Rivash, sec 226) forbade sewing baby clothes during hol ha-moed for a newborn’s circumcision despite the parents’ desire to dress him properly and festively for the event. One of Rivash’s rationales is that since all understand that new clothes cannot be sewn on hol ha-moed – because Hazal forbade it, kevod ha-beriyyot cannot be invoked to circumvent this rabbinic prohibition. Similarly, one cannot invoke kevod ha-beriyyot to allow women to receive aliyyot, because all understand that this has been synagogue procedure for two millennia and that the Rabbis of the Talmud themselves prohibited it.

(9) Rivash (ibid.) and Havot Yair (sec. 95) and others rule against extending the leniency of kevod ha-beriyyot beyond those instances explicitly discussed by Hazal – honor of the deceased (כבוד המת), personal hygiene dealing with excrement, undress, and the wholeness of the family unit. New cases may not be comparable in their nature or severity to the original examples. Indeed, as noted by Prof. Blidstein and R. Aharon Lichtenstein,[20] throughout the two millennia of post-Talmudic responsa literature, kevod ha-beriyyot is rarely if ever cited as the sole or even major grounds for overriding a bona fide rabbinic ordinance. It always appears as one of many additional reasons to be lenient (snif le-hakel). This is indeed the case in nearly all the instances cited at length by R. Daniel Sperber in his book Darka shel Halakha.

What’s more, in those instances where kevod ha-beriyyot is invoked essentially alone, it is because the matter being deferred is a mere, often unbased, stringency (humra be-alma). For example, the custom in some communities prohibiting menstruants to enter the synagogue – which Prof. Sperber has returned to repeatedly (Sperber, pp. 74) – is what the posekim call a humra ve-silsul be-alma. Hence, the fact that even in such stringent communities, menstruants visited the sanctuary on the High Holidays – would be a classic example of kevod ha-beriyyot overruling a humra be-alma.

Now Prof. Sperber will respond, that he too would only invoke kevod ha-beriyyot in the case of women’s aliyyot. After all, there is no real down side – at most we have only violated a recommendation. However, as we have argued above, “aval amru hakhamim” is not a recommendation by women’s aliyyot – but a prohibition le-khathilla. What’s more, a woman who gets an aliyya without reading for herself or who is only the ba’alat keria is responsible for generating berakhot levatala. We have also argued that Prof. Sperber has improperly invoked kevod ha-beriyyot for the case of women’s aliyyot because he has not taken into consideration the kelalim of the gedolei ha-posekim.

I would like to close with one last point. Despite the fact that we strongly disagree with Prof. Sperber’s conclusion, he after all did what a Torah scholar is bidden to do. He made a creative suggestion, documented his arguments, published his suggestion in the rabbinic literature for all to examine, and awaits criticism or approval. After thrashing out the issue, back and forth – one hopefully will be able to discern where the truth lies.[21]

However, we take issue with those who would enact women’s aliyyot in practice, hastily undoing more than two millennia of halakhic precedent – simply because an article or two has appeared on the subject. Considering the novelty of this innovation, religious integrity and sensitivity requires serious consultation with renowned halakhic authorities of recognized stature – prior to acting on such a significant departure from normative halakha. It often takes several years time before a final determination can be reached as to whether or not a suggested innovation meets these standards. But that cannot provide adequate justification for haste.

The halakhic process has always been about the honest search for truth – Divine truth.[22] To adopt one particular approach – simply because it yields the desired result, lacks intellectual honesty and religious integrity. It is equivalent to shooting the arrows and then drawing the bull’s-eye. To paraphrase Prof. Yeshayahu Leibowitz: we must always ask ourselves whether we are in reality serving the Divine will or our own.[23]

Notes:

[1] R. Daniel Sperber, Darka shel Halakha – Keri’at Nashim baTorah: Perakim biMediniyyut Pesikah (Jerusalem: Reuven Mass, 2007). The phrase “lo zu ha-derekh” used in the title of this book review appears in Bava Metsi’a 37b and Kalla Rabati 9:19. This critique is essentially the combined text of two lectures given at Bar-Ilan University (17 March 2008) and at Lander Institute, Jerusalem (4 May 2008), and is based on a forthcoming article by Aryeh A. Frimer and Dov I. Frimer, “Women, Kri’at haTorah and Aliyyot” (in review). A complete list of sources and references will be fully delineated therein. The author would like to acknowledge the kind and gracious support of this research afforded by The Bellows Family Foundation. The author also wishes to express heartfelt thanks to Prof. Dov I. Frimer for reviewing the manuscript and for his many valuable and insightful comments.

[2] See, for example, Maimonides, Yad, Hil. Tefilla, sec. 12, parag. 17; R. Joseph Karo, Shulhan Arukh, O.H., sec. 282, parag. 3.

[3] R. Mendel Shapiro, “Qeri’at ha-Torah by Women: A Halakhic Analysis,” The Edah Journal 1:2 (Sivan 5761): 1-55 – available online here; R. Mendel Shapiro and R. Yehuda Herzl Henkin, “Concluding Responses to Qeri’at ha-Torah for Women,” ibid., 1-4 – available online; R. Mendel Shapiro, “Communications,” Tradition 40:1 (Spring 2007): 107-116.

[4] See Aryeh A. Frimer and Dov I. Frimer, “Women, Kri’at haTorah and Aliyyot,” (forthcoming).

[5] (a) R. Daniel Sperber, “Congregational Dignity and Human Dignity: Women and Public Torah Reading,” The Edah Journal 3:2 (Elul 5763): 1-14 – available online; (b) R. Daniel Sperber, “kevod ha-tsibbur uKhevod haBeriyyot,” De’ot 16 (Sivan 5763, June 2003): 17-20 and 44 – available online; (c) R. Daniel Sperber, Darka shel Halakha – Keri’at Nashim baTorah: Perakim biMediniyyut Pesikah (Jerusalem: Reuven Mass, 2007). (d) See also a recording of a lecture given by R. Sperber in Modi’in, Israel, July 3, 2006 – available online.

[6] See note 4, supra.

[7] See, inter alia, R. Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, miBeit Midrasho shel ha-Rav, Hilkhot Keri’at haTorah, p. 31; Shiurei haRav haGaon Rabbi Yosef Dov haLevi Soloveitchik zatsa”l al Inyanei Tsitsit, Inyanei Tefillen veHilkhot Keri’at haTorah, p. 154.

[8] (a) R. Nahum Rakover, haHagana al Kevod haAdam (Jerusalem: Misrad haMishpatim, 5738); (b) R. Nahum Rakover, “Kevod haBeriyyot,” Shana beShana (5742): 221-233; (c) R. Nahum Rakover, Gadol Kevod haBeriyyot: Kevod ha-Adam ke-Erekh-Al (Jerusalem: Sifriyat ha-Mishpat ha-Ivri, 1998).

[9] (a) R. Ya’akov (Gerald J.) Blidstein, “Gadol Kevod haBeriyyot – Iyyunom beGilguleha shel Halakha,” Shenaton ha-Mishpat ha-Ivri 9-10 (5742-5743): 127-185; (b) R. Ya’akov (Gerald J.) Blidstein, “Kevod ha-Beriyyot uKevod haAdam,” in Joseph David, ed., She’eila shel Kavod – Kevod haAdam keErekh Mussari Elyyon baHevra haModernit (haMakhon haYisraeli leDemokratiya and Magnes Press: Jerusalem, 2006), 97-138 – available online.

[10] (a) R. Aharon Lichtenstein, “Kevod haBeriyyot,” Mahanayim 5 (Iyar 5753): 8-15; (b) R. Aharon Lichtenstein, “Kevod Ha-beriyyot: Human Dignity in Halakha” – this is an English translation of reference 10a – available online; (c) R. Aharon Lichtenstein, “Kevod haBeriyyot” – available online; (d) R. Aharon Lichtenstein, “‘Mah Enosh’: Reflections on the Relation between Judaism and Humanism,” Torah u-Madda Journal 14 (2006-2007): 1-61, p. 30ff – available online.

[11] (a) R. Daniel Z. Feldman, The Right and the Good: Halakha and Human Relations (Brooklyn, NY: Yashar Books, 2005 – Expanded edition), 197-214 (chapter 14); (b) R. Daniel Z. Feldman, “K’vod haBeriyyot – Human Dignity,” shiur (18 March 2005) available online; (c) R. Daniel Z. Feldman, “Kavod haBeriyos,” audio shiur (26 June 2007) available online.

[12] (a) “Kevod haBeriyyot,” Encyclopedia Talmudit 27, pp. 477-542; (b) R. Chaim Zev (Wolf) Reines, “Kevod haBeriyyot,” Sinai 27:7-12 (159-164; Nisan-Elul 5710): 157-168; (c) R. Israel Shepansky, “Gadol Kevod haBeriyyot,” Or haMizrah 33:3-4 (118-119; Nisan-Tammuz, 5745): 217-228; (d) Danny Eivers, “Kevod haBeriyyot,” Talelei Orot 7 (5757): 125-135 – available online; (e) R. Benayahu Broner, “Kevod haBeriyyot keBitui leHofesh haPerat,” Talelei Orot 8 (5758-5759) – available online. (f) R. Mark Dratch, “The Divine Honor Roll: Kevod ha-Beriyyot (Human Dignity) in Jewish Law and Thought,” (2001; revised 2006) – available online; (g) R. Hershel Schachter, “Kavod haBriyot,” audio shiur available online; (h) R. Mosheh Lichtenstein, “G-d’s Handiwork: Human Dignity as a Halakhic Factor (Part 2)” – available online; (i) Hershey H. Friedman, “Human Dignity in Jewish Law,” 2005 – available online; (j) R. Daniel Sperber, supra, note 5; (k) Eliezer ben-Shlomo, “kevod haAdam mul Shelom haTsibbur beHashpalat Asir,” Tehumin 17 (5754): 136-144.

[13] Rabbi Judah ben Isaac Ayash, Resp. Bet Yehuda, O.H. 58, s.v. “veKhi teima”; R. Israel Shepansky, supra, note 12c based on Rabbenu Nissim and R. Eliezer ben Nathan (Ra’avan).

[14] Rabbi Judah ben Isaac Ayash, Resp. Bet Yehuda, O.H. 58, s.v. “veKhi teima”; R. Israel Shepansky, supra, note 12c based on Rabbenu Nissim and R. Eliezer ben Nathan (Ra’avan)

[15] Resp. Rosh, Kelal 5, Din 8; Resp. Maharam ben Barukh, III, sec. 387.

[16] See the comments on point of R. Aharon Lichtenstein, supra note 10a and b.

[17] R. Meir Simha of Dvinsk, Or Same’ah, Bava Metsia 32b; Resp. Mishpitei Ouziel, I, Y.D., sec. 28, s.v. “Ulam ma she-katav” – reprinted in Piskei Ouziel biShe’eilot haZeman, sec. 32, s.v. “Ulam ma she-katav,” pp. 175-176; R. Joseph B. Soloveitchick, Divrei Hashkafa, pp. 234-235; R. Joseph B. Soloveitchick cited by R. Zvi (Hershel) Schachter, “miPeninei Rabbenu,” Beit Yitshak 36 (5764): 320ff; R. Jacob Israel Kanievsky, Karaina deIggarta, I, secs. 162 and 163; R. Avigdor Nebenzahl, “Without Fear of G-d there is nothing,” Parsha Values (Yeshiva Netiv Aryeh) – vaYera 5762, available online; R. Yehudah Herzl Henkin, “Amirat sheLo Asani Isha beLahash,” mi-Peirot ha-Kerem: An Anniversary Book for Yeshivat Kerem BeYavneh (5764): 75-81, sec. B.1, s.v. “laAharona”; R. Yehudah Herzl Henkin, Resp. Bnai Vanim, IV, sec. 1, no. 3, “laAharona”; R. Yehudah Herzl Henkin, personal communication to Aryeh A. Frimer (26 November 2007); R. Ari Friedman, Kavod haBerios, Parsha Encounters (Chicago Community Kollel), 8 Tammuz 5765 (15 July 2005) – available online.

[18] Sifra, Parsheta 2; Hagiga 16b.

[19] R. Daniel Sperber, Darka shel Halakha, supra, note 5, pp. 72-74 and note 98 therein.

[20] See: R. Ya’akov (Gerald J.) Blidstein, supra, note 9a, pp. 170-172; R. Aharon Lichtenstein, supra, note 10a, pp. 14-15 and note 10b.

[21] A series of critiques of the analyses of R. Shapiro and R. Sperber have recently been published; see: (a) R. Eliav Shochetman, “Aliyyat Nashim leTorah,” Sinai 135-136 (2005): 271-349; (b) R. Gidon G. Rothstein, ”Women’s Aliyyot in Contemporary Synagogues,” Tradition 39:2 (Summer 2005): 36-58, and R. Gidon Rothstein, “Communications,” Tradition 40:1 (Spring 2007): 118-121. (c) R. Ephraim Bezalel Halivni, Bein haIsh laIsha (Jerusalem: Shai Publishers, 5767): 58-71, 102-105, and in the English section, 12-21. In addition, two prominent religious Zionist rabbis have published responsa highly critical of the practices of Jerusalem’s Kehillat Shira Hadasha in which women are given aliyyot. See: R. Jacob Ariel, “Bet Kenesset Shira Hadasha” available online; R. Jacob Ariel, “Aliyyat Nashim laTorah: Hillul haKodesh,” Hatsofe (12 July 2007) – available online; R. Dov Lior, “Minyanim Mehudashim beHishtatfut Nashim” available online. See also the recent responsa of R. Ahiyya Shlomo Amitai (rabbi of Kibbutz Sedei Eliyahu), “Madu’a Nashim Lo Olot laTorah,” available online; R. Rami Rahamim Berakhyahu (rabbi of Yishuv Talmon), Resp. Tel Talmon, II, sec. 91, note 1, p. 113.

[22] See: R. Aryeh A. Frimer, “Feminist Innovations in Orthodoxy Today: Is Everything in Halakha – Halakhic?” JOFA Journal, 5:2 (Summer 2004/Tammuz 5764): 3-5 – available online.

[23] R. Prof. Yeshayahu Leibowitz, “On Faith and Science,” Rabbi Moshe Zev Kahn – Mr. Samuel G. Bellows Memorial Lecture, Rabbi Jacob Berman Community Center – Tiferet Moshe Synagogue, Rehovot Israel (April 1986).