Some Assorted Comments and a Selection from my Memoir, part 1

By Marc B. Shapiro

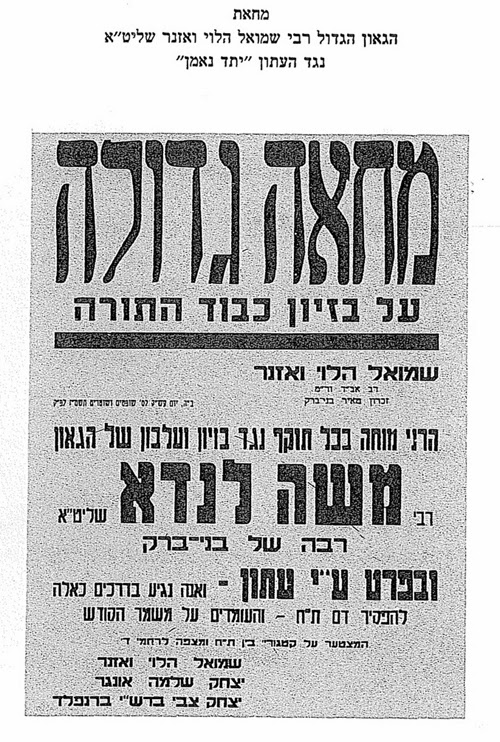

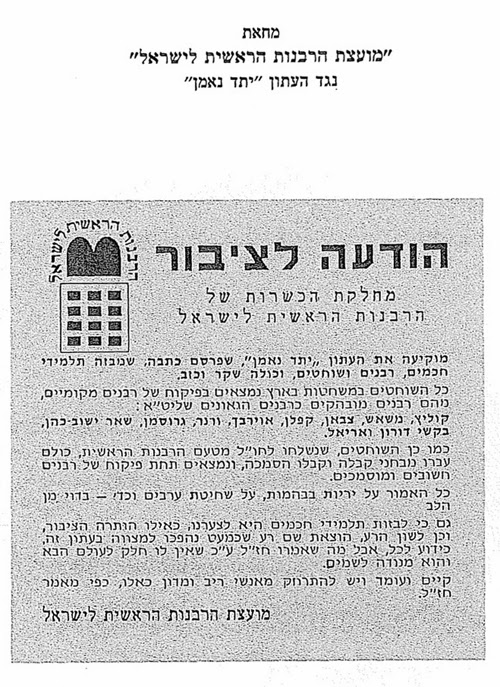

1. Fifty years ago R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg spoke about the fraudulence that was found in the Orthodox world. Unfortunately, matters have gotten much worse since his time. I am not referring to the phony pesakim in the names of great rabbis that appear plastered all over Jerusalem, and from there to the internet. Often the damage has been done before the news comes out that the supposed pesak was not actually approved by the rav, but was instead put up by an “askan” or by a member of the rabbi’s “court”. I am also not referring to the fraudulent stories that routinely appear in the hagiographies published by Artscroll and the like, and were also a feature in the late

Jewish Observer. These are pretty harmless, and it is hard to imagine anyone with sophistication being taken in. Finally, I am also not referring to the falsehoods that constantly appear in the

Yated Neeman. I think everyone knows that this newspaper is full of lies and in its despicable fashion thinks nothing of attempting to destroy people’s reputations, all because their outlooks are not in accord with whatever Daas Torah

Yated is pushing that week.

[1]I am referring to something much more pernicious, because the falsehoods are directed towards the intellectuals of the community, and are intended to mislead them. There was a time when in the haredi world a distinction was made between the masses, whom it was permitted to mislead with falsehoods, and the intellectuals who knew the truth and who were part of the “club” that didn’t have to bother with the censorship that is ubiquitous in haredi world.

Yet I have recently seen many examples that show that even in the world of the intellectuals, fraudulence has begun to surface. Let me note an example that was recently called to my attention by Rabbi Yitzchak Oratz, and it is most distressing precisely because it is a son who is responsible for the lie. In an issue of the popular journal

Or Yisrael, R. Yehudah Heller from London mentioned that the late R. Yerucham Gorelik, a well-known student of R. Velvel of Brisk, had taught Talmud at Yeshiva University.

[2] Heller used this example to show that one can teach Torah in an institution even if the students’ devotion to Torah study leaves something to be desired.

In the latest issue of

Or Yisrael (Tishrei, 5770), p. 255, Heller publishes a letter in which he corrects what he had earlier written. He was contacted by Gorelik’s son, R. Mordechai Leib Gorelik. The only thing I know about the younger Gorelik is that he appears to be quite extreme. He published an essay in

Or Yisrael attacking the Artscroll Talmud and his reason was simply incredible. He claimed that anything that tries to make the study of Talmud easier is to be condemned. He also argued that Talmud study is not for the masses, but only for the elite. Obviously, the latter don’t need translations. According to Gorelik, if the masses want to study Torah, they can study halakhah or Aggadah and Mussar. If they want to study Talmud, then they must do it the way it used to be studied, with sweat, but they have no place in the beit midrash with their Artscroll crutches.

[3]Apparently it bothers Gorelik that his colleagues might think that his father actually taught Talmud at YU. So he told Heller the following, and this is what appears in Or Yisrael: R. Yerucham Gorelik never taught Talmud at YU, and on the contrary, he thought that there was a severe prohibition (issur hamur) in both studying and teaching Talmud at this institution, even on a temporary basis, and even in order “to save” the young people in attendance there. The only subject he ever taught at YU was “hashkafah”.

The Sages tell us that “people are not presumed to tell a lie which is likely to be found out” (

Bekhorot 36b). I don’t think that they would have made this statement if they knew the era we currently live in.

[4] Here you have a case where literally thousands of people can testify as to how R. Gorelik served as a Rosh Yeshiva at YU for forty years, where you can go back to the old issues of the YU newspapers, the yearbooks, Torah journals etc. and see the truth. Yet because of how this will look in certain extremist circles, especially with regard to people who are far removed from New York and are thus gullible in this matter, R. Gorelik’s son decides to create a fiction.

I understand that in his circle the younger Gorelik is embarrassed that his father taught Talmud at YU. I also assume that he found a good heter to lie in this case. After all, it is kavod ha-Torah and the honor of his father’s memory, because God forbid that it be known that R. Gorelik was a Rosh Yeshiva at YU. However, I would only ask, what happened to hakarat ha-tov? YU gave R. Gorelik the opportunity to teach Torah at a high level. It also offered him a parnasah. Without this he, like so many of his colleagues, would have been forced into the hashgachah business, and when this wasn’t enough, to schnorr for money, all in order to put food on the table.

This denial of any connection to YU is part of a larger pattern. In my last post I mentioned how R. Poleyeff’s association with the school was erased. Another example is how R. Soloveitchik appears on the title page of one sefer as “Av Beit Din of Boston.” And now R. Gorelik’s biography is outrageously distorted.

[5] Yet in the end, it is distressing to realize that the rewriting of history might actually work. In fifty years, when there are no more eyewitnesses alive to testify to R. Gorelik’s shiurim, how many people will deny that he ever taught at YU? Any written record will be rejected as a YU-Haskalah forgery, or something that God miraculously created to test our faith, all in order to avoid the conclusion that an authentic Torah scholar taught at YU.

[6] I have no doubt that the editor of

Or Yisrael, coming from a world far removed from YU, is unaware of the facts and that is why he permitted this letter to appear. I am certain that he would not knowingly permit a blatant falsehood like this to sully his fine journal.

2. Since I spoke so much about R. Hayyim Soloveitchik in the last two posts, let me add the following: The anonymous

Halikhot ha-Grah (Jerusalem, [1996]), p. 4, mentions the famous story recorded by R. Zevin, that in a difficult case of Agunah R. Hayyim asked R. Yitzhak Elhanan’s opinion, but all he wanted was a yes or no answer. As R. Zevin explained, quoting those who were close to R. Hayyim, if R. Yitzhak Elhanan gave his reasoning then R. Hayyim would certainly have found things with which he disagreed, but he knew that in terms of practical halakhah he could rely on R. Yitzhak Elhanan.

[7] Halikhot ha-Grah rejects R. Zevin’s explanation. Yet the same story, and explanation, were repeated by R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik.

[8] In addition, a similar story, this time involving R. Hayyim and R. Simcha Zelig, is found in

Uvdot ve-Hangagot le-Veit Brisk, vol. 4, pp. 35-36. Thus, there is no reason to doubt what R. Zevin reports.

[9] Mention of

Halikhot ha-Grah would not be complete without noting that it takes a good deal of material, without acknowledgment and sometimes word for word, from R. Schachter’s

Nefesh ha-Raf. Of course, this too is done in the name of kavod ha-Torah.

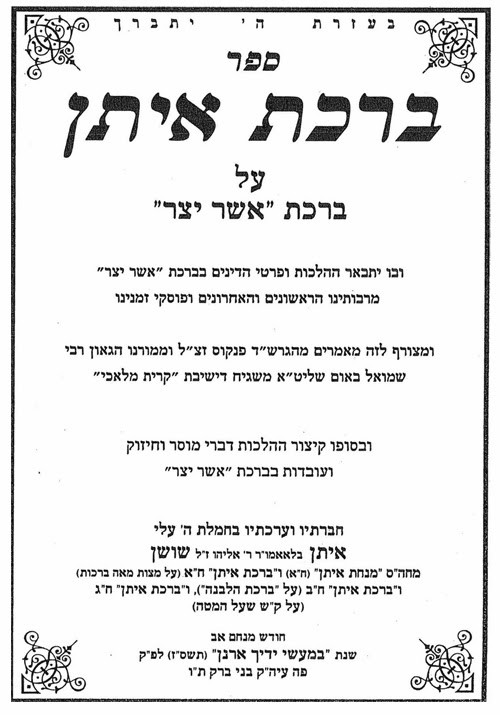

3. Many posts on this blog have discussed how we now have entire books on topics concerning which until recent years a few lines sufficed. Haym Soloveitchik also made this point in “Rupture and Reconstruction.” Here is another example, the book Birkat Eitan by R. Eitan Shoshan.

This is a 648 page (!) book devoted to the blessing Asher Yatzar, recited after going to the bathroom. Shoshan has an even larger book devoted to the Shema recited before going to sleep.

4. In a previous post

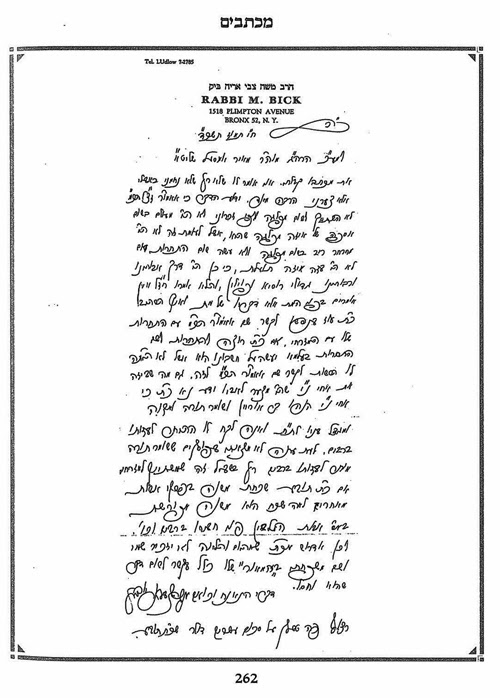

[10] I mentioned that R. Moshe Bick’s brother was the Judaic scholar and communist Abraham Bick (Shauli). Before writing this I confirmed the information, but as we all know, oftentimes such “confirmations” are themselves incorrect. I thank R. Ezra Bick for providing me with the correct information, and the original post has been corrected.

R. Moshe and Abraham were actually somewhat distant cousins.

[11] Abraham was the son of R. Shaul Bick (and hence the hebraicized last name, Shauli), who was the son of R. Yitzchak Bick, who was the chief rabbi of Providence, RI, in the early 1930’s. R. Yitzchak was the son of R. Simcha Bick, who was rav in Mohiliv, Podolia. R. Simcha Bick had a brother, R. Zvi Aryeh Bick, who was rav in Medzhibush. His son was R. Hayyim Yechiel Mikhel Bick, was also rav in Medzhibush (d. 1889). His son was also named Hayyim Yechiel Mikhel Bick (born a few months after his father’s premature death), and he was rav in Medzhibush from 1910 until 1925, when he came to America. His son was R. Moshe Bick.

R. Ezra Bick also reports that after the Second World War, when Abraham Bick was in the U.S. working as an organizer for communist front organizations, he was more or less cut off by his Orthodox cousins in Brooklyn.

R. Moshe Bick’s brother, Yeshayah (R. Ezra’s father), was a well-known Mizrachi figure. In his obituary for R. Hayyim Yechiel Mikhel Bick, R. Meir Amsel, the editor of

Ha-Maor, mentioned how Yeshayah caused his father much heartache with his Zionist activities.

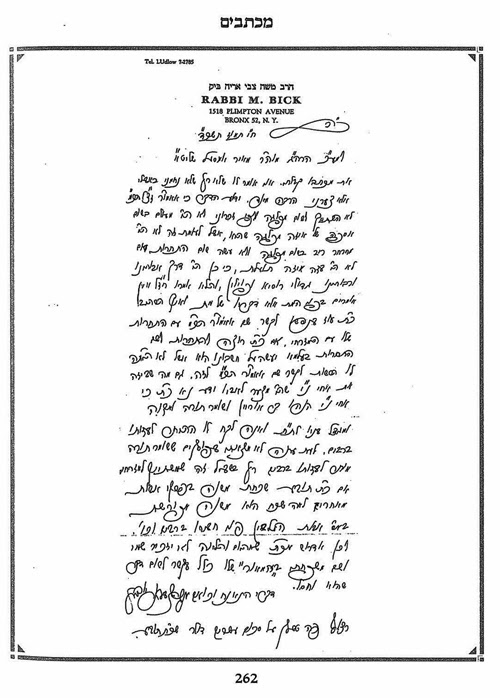

[12] This article greatly hurt R. Moshe Bick and he insisted that Amsel never again mention him or his family in

Ha-Maor. In fact, as R. Ezra Bick has pointed out to me, rather than causing his father heartache, R. Hayyim Yechiel actually encouraged Yeshayah in his Zionist activities.

R. Bick’s letter is actually quite fascinating and I give the Amsel family a lot of credit for including it in a recent volume dedicated to R. Meir Amsel. I have never seen this sort of letter included in a memorial volume, as all the material in such works is supposed to honor the subject of the volume. Yet here is a letter that blasts Amsel, and they still included it.

[13] They also included a letter from R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg in which he too criticizes Amsel for allowing personal attacks to be published in his journal. It takes a lot of strength for children to publish such letters and they have earned my admiration for doing so.

When I first mentioned R. Moshe Bick, I also noted that he was opposed to young people getting married too quickly. He therefore urged that boys and girls go out on a number of dates before deciding to get engaged. Needless to say, the haredi world was furious at this advice. R. Dovid Solomon reported to me the following anecdote: When the Klausenberger Rebbe told R. Bick how opposed he was to the latter’s advice, R. Bick responded: “That’s because you are mesader kidushin at all the marriages. But I am the one who is mesader all the gittin!”

5. In previous postings I gave three examples of errors in R. Charles B. Chavel’s notes to his edition of Nahmanides’ writings. For each of these examples my points were challenged and Chavel was defended. Here is one more example that I don’t think anyone will dispute. In Kitvei ha-Ramban, vol. 1, p. 148, Nahmanides writes:

ובזה אין אנו מודים לספר המדע שאמר שהבורא מנבא בני אדם.

In his note Chavel explains ספר המדע to mean:

לדבר הידוע, יעללינעק מגיה פה שצ”ל: לרב הידוע.

Yet the meaning is obvious that Nahmanides is referring to Maimonides’

Sefer ha-Mada, where he explains the nature of prophecy.

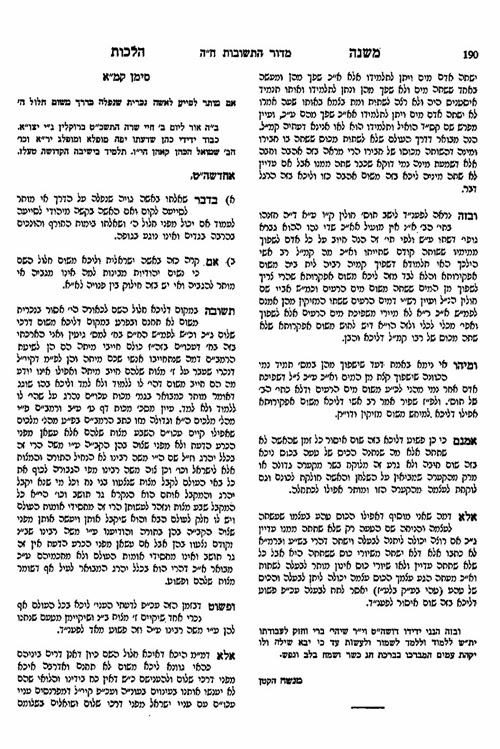

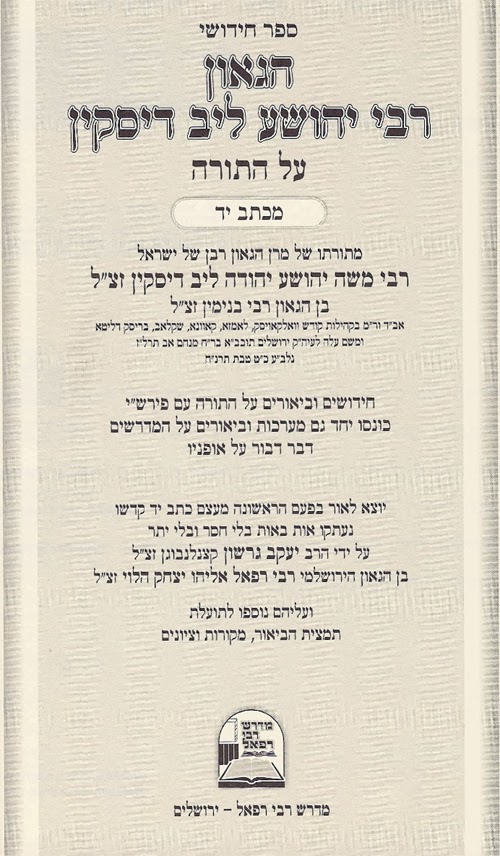

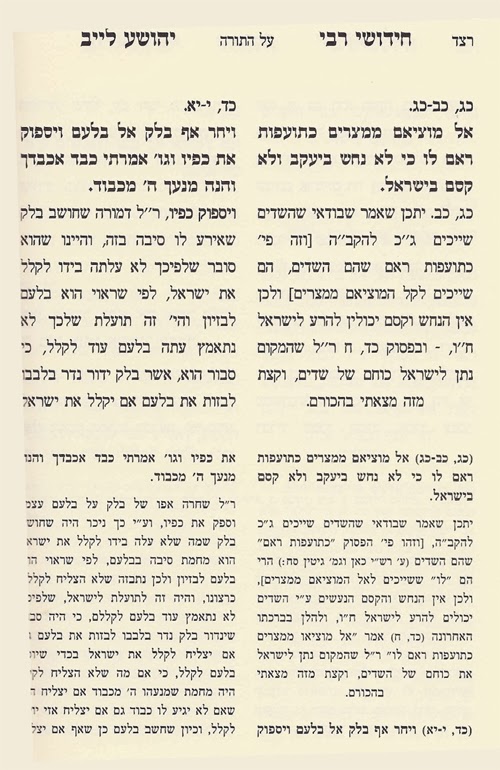

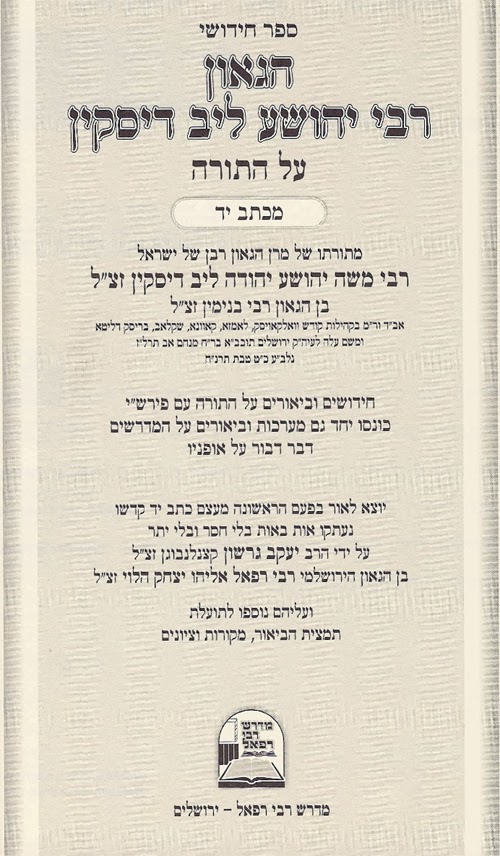

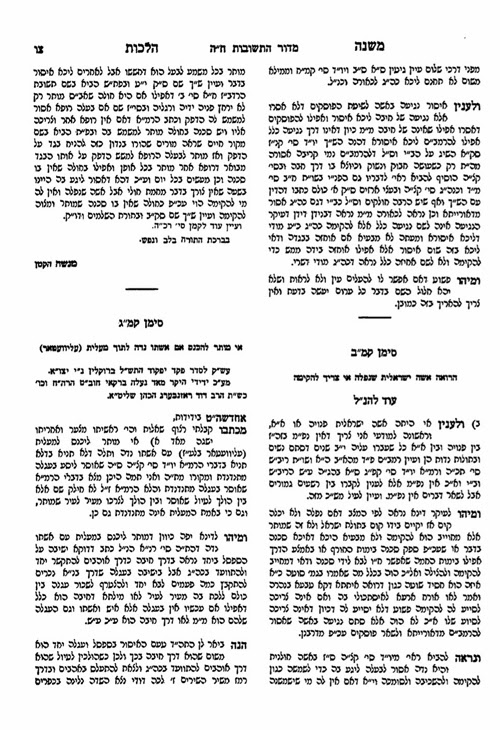

[14]5. In 2008 a Torah commentary from R. Joshua Leib Diskin was published. Here is the title page.

The book even comes with a super-commentary of sorts. This is completely unnecessary but shows how greatly the editor/publisher values the work. Diskin is a legendary figure and was identified with the more extreme elements of the Jerusalem Ashkenazic community. For this reason he often did not see eye to eye with R. Samuel Salant.

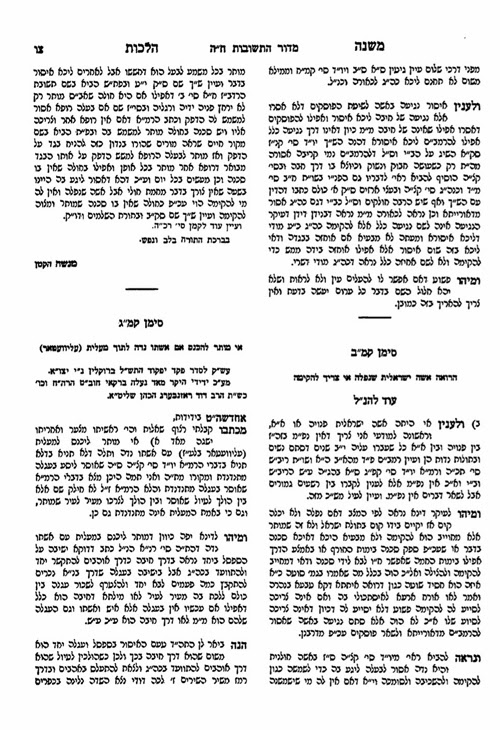

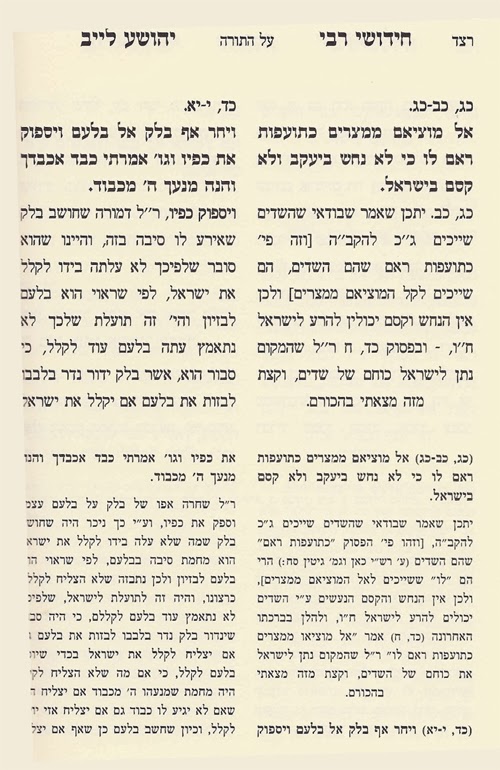

Here is a page from this new commentary.

In his comment to Num. 23:22-23, Diskin quotes a book called Ha-Korem. This is a commentary on the Torah and some other books of the Bible by Naphtali Herz Homberg, a leading Maskil who worked for the Austrian government as superintendent of Jewish schools and censor of Jewish books. This is what the Encyclopedia Judaica says about him:

Homberg threatened the rabbis that if they did not adapt themselves to his principles the government would force them to do so. . . . Homberg was ruthless in denouncing to the authorities religious Jews who refused to comply with his requirements, and in applying pressure against them. In his official memoranda he blamed both the rabbis and the Talmud for preventing Jews from fulfilling their civic duties toward the Christian state. . . . Homberg recommended to the authorities that they disband most traditional educational institutions, prohibit use of the Hebrew language, and force the communal bodies to employ only modern teachers. . . In his book Homberg denied the belief in Israel as the chosen people, the Messiah, and the return to Zion, and tried to show the existence of an essential identity between Judaism and Christianity. . . . Homberg incurred the nearly universal hatred of his Jewish contemporaries.

Incredibly, it is from his commentary that Diskin quoted. The editor didn’t know what Ha-Korem was, but almost immediately after publication someone let him in on the secret. All copies in Israeli seforim stores were then recalled in order that the offending page be “corrected”. I am told that the first printing is now impossible to find in Israel. When I was informed of this story by R. Moshe Tsuriel, I contacted Biegeleisen who fortunately had just received a shipment from Israel, sent out before the books were embargoed. Presumably, my copy will one day be a collector’s item.

The one positive thing to be said about Homberg is that he wrote a very good Haskalah Hebrew. I was therefore surprised when I saw the following in David Nimmer’s otherwise fantastic article in Hakirah 8 (2009): “We begin with Herz Homberg, a minor functionary who wrote in German since his Hebrew skills were poor” (p. 73). Since German was the last language Homberg learnt, I was curious as to how Nimmer was misled. He references Wilma Abeles Iggers, The Jews of Bohemia and Moravia (Detroit, 1992), p. 14. Yet Nimmer misunderstood this source. Iggers writes as follows, in speaking of the mid-eighteenth century: “Use of Hebrew steadily decreased, even in learned discussions. Naftali Herz Homberg, for example, asked his friend Moses Mendelssohn to correspond with him in German rather than in Hebrew.” All that this means is that Homberg wanted to practice his German, and become a “cultured” member of Mendelssohn’s circle, and that is why he wanted to correspond in this language. In this he is little different than so many others like him who arrived in Berlin knowing only Hebrew and Yiddish. Each one of them had a different story as to how they learnt German. According to the Encyclopedia Judaica, in 1767, when he was nineteen years old, Homberg “began to learn German secretly.”

6. In a previous post I noted the yeshiva joke that R. Menasheh Klein’s books should be called Meshaneh Halakhot, instead of Mishneh Halakhot. Strangely enough, if you google “meshaneh halakhot” you will find that the books are actually referred to this way by a few different people, including, in what are apparently Freudian slips, B. Barry Levy and Daniel Sperber. In fact, Klein’s books are not the first to be referred to in this sort of way. In his polemic against Maimonides, R. Meir Abulafia writes (Kitab al Rasail [Paris, 1871), p. 13):

הוא הספר הנקרא משנה תורה, ואיני יודע אם יש אם למסורת ואם יש אם למקרא.

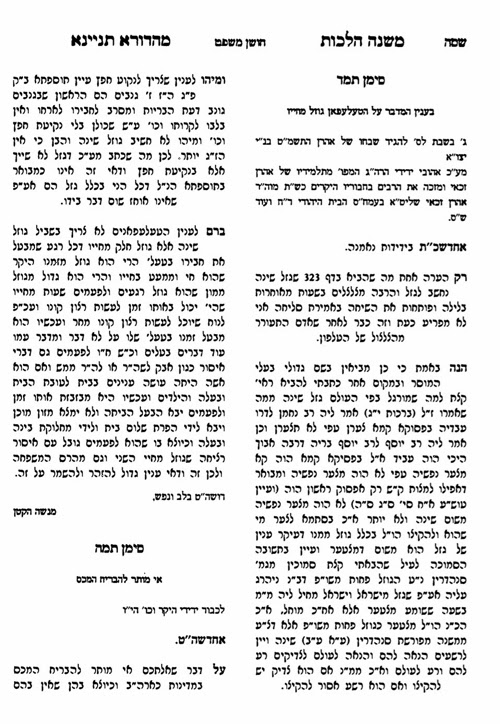

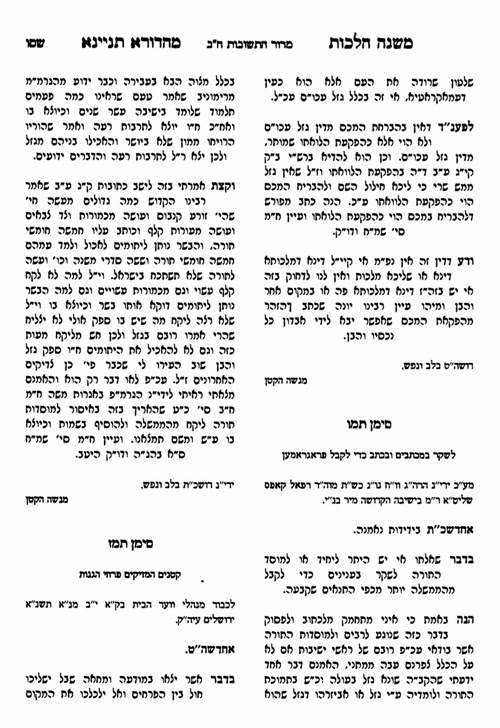

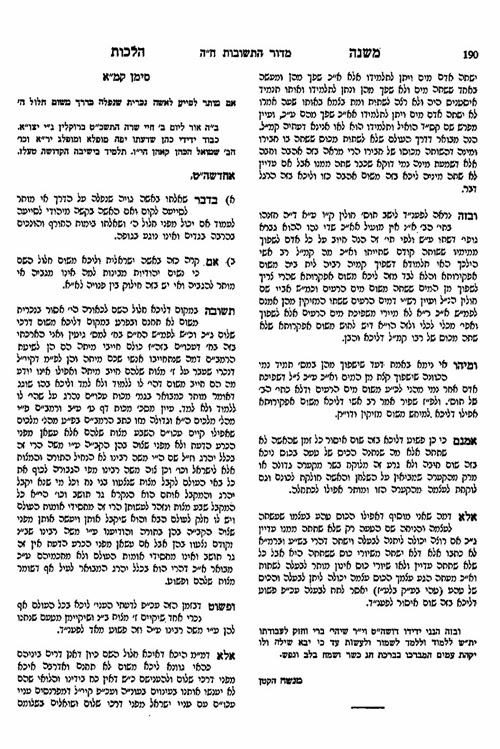

Abulafia is mocking Maimonides’ greatest work, and wondering if perhaps it should be called Meshaneh Torah! As for Klein, there is a good deal that can be said about his prolific writings, and they await a comprehensive analysis. When thinking about Meshaneh Halakhot, I often recall following responsum, which appears in Mishneh Halakhot, vol. 5, no. 141, and which I am too embarrassed to translate.

A well-known talmid hakham pointed out to me something very interesting. Normally we understand hillul ha-shem to mean that a non-Jew will see how Jews behave and draw the wrong conclusions of what Torah teachings are all about. However, in this responsum we see the exact opposite. The hillul ha-shem is that the non-Jew will draw the right conclusion! Yet the truth is that this understanding of hillul ha-shem is also very popular and is used by R. Moses Isserles, as we will soon see..

Here is another responsum that will blow you off your seats, from Mishneh Halakhot, New Series, vol. 12, Hoshen Mishpat no. 445.

If you want to understand why three hasidic kids are sitting in a Japanese jail, this responsum provides all you need to know. Can anyone deny that it is this mentality that explains so much of the illegal activity we have seen in recent year? Will Agudat Israel, which has publicly called for adherence to high ethical standards in such matters, condemn Klein? Will they declare a ban on R Yaakov Yeshayah Blau’s popular

Pithei Hoshen, which explains all the halakhically permissible ways one can cheat non-Jews? You can’t have it both ways. You can’t declare that members of your community strive for the ethical high ground while at the same time regard

Mishneh Halakhot,

Pithei Hoshen, and similar books as valid texts, since these works offer justifications for all sorts of unethical monetary behavior. The average Orthodox Jew has no idea what is found in these works and how dangerous they are. Do I need to start quoting chapter and verse of contemporary halakhic texts that state explicitly that there is no prohibition to cheat on one’s taxes?

[15] Pray tell, Agudah, are we supposed to regard these authors as legitimate halakhic authorities?

I have no doubt that there was a time that the approach found here was acceptable. In an era when Jews were being terribly persecuted and their money was being taken, the non-Jewish world was regarded as the enemy, and rightfully so. Yet the fact that pesakim reflecting this mindset are published today is simply incredible. Also incredible is that R. David Zvi Hoffmann’s

Der Schulchan-Aruch und die Rabbinen über das Verhältniss der Juden zu Andersgläubigen, a classic text designed to show that Jewish law does not discriminate monetarily against contemporary Gentiles, has not yet been translated. Hoffmann’s approach was shared by all other poskim in Germany, who believed that any discriminatory laws were simply no longer applicable.

[16] R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg stated that we must formally declare that this is what we believe. Can Agudah in good conscience make such a declaration, and mean it?

The truth is that there is an interesting sociological divide on these matters between the Modern Orthodox and the haredi world. Here is an example that will illustrate this. If a Modern Orthodox rabbi would advocate the following halakhah, quoted by R. Moses Isserles,

Hoshen Mishpat 348:2,

[17] he would be fired.

[18]טעות עכו”ם כגון להטעותו בחשבון או להפקיע הלואתו מותר ובלבד שלא יודע לו דליכא חילול השם.

If I am wrong about this, please let me know, but I don’t believe that any Modern Orthodox synagogue in the country would keep a rabbi who publicly advocated this position.

[19] Indeed, R. Moses Rivkes in his

Be’er ha-Golah on this halakhah wants people to know that they shouldn’t follow this ruling.

[20] See also Rivkes,

Be’er ha-Golah, Hoshen Mishpat 266:1, 383:1, and his strong words in

Hoshen Mishpat 388:12 where he states that the communal leaders would let the non-Jews know if any Jews were intent on cheating them. Today, people would call Rivkes a

moser.

I believe that if people in the Modern Orthodox world were convinced that Rama’s ruling is what Jewish ethics is about, very few of them would remain in Orthodoxy. In line with what Rivkes states, this halakhah has been rejected by Modern Orthodoxy and its sages, as have similar halakhot. As mentioned, Hoffmann’s Der Schulchan-Aruch is the most important work in this area. Yet today, most people will simply cite the Meiri who takes care of all of these issues, by distinguishing between the wicked Gentiles of old and the good Gentiles among whom we live. Thus, whoever feels that he is living in a tolerant environment can adopt the Meiri’s position and confidently assert that Rama is not referring to the contemporary world.

Yet what is the position of the American haredi world? If they accept Rama’s ruling, and don’t temper it with Meiri, then in what sense can the Agudah claim that they are educating their people to behave ethically in money matters? Would they claim that Rama’s halakhah satisfies what we mean by “ethical” in the year 2009? Will they say, as they do in so many other cases, that halakhah cannot be compared to the man-made laws of society and cannot be judged by humans? If that is their position, I can understand it, but then let Aish Hatorah and Ohr Sameach try explaining this to the potential baalei teshuvah and see how many people join the fold. If this is their position, then all the gatherings and talks about how one needs to follow dina de-malchuta are meaningless, for reasons I need not elaborate on. Furthermore, isn’t all the stress on following dina de-malchuta revealing? Why can’t people simply be told to do the right thing because it is the right thing? Why does it have to be anchored in halakhah, and especially in dina de-malchuta? Once this sort of thing becomes a requirement because of halakhah, instead of arising from basic ethics, then there are 101 loopholes that people can find, and all sorts of

heterim as we saw in Klein’s responsum. I would even argue that the fact that one needs to point to a halakhic text to show that it is wrong to steal is itself a sign of our society’s moral bankruptcy.

[21]7. In Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters I stated that Maimonides nowhere explicitly denies the existence of demons, yet this denial is clearly implied throughout his writings. It was because Maimonides never explicitly denied them that so many great sages refused to accept this, and assumed that Maimonides really did believe in demons. (In my book I cited many who held this position.) I first asserted that Maimonides never explicitly denied demons in my 2000 article on Maimonides and superstition, of which the second chapter in my new book is an expanded treatment. While working on the original article I was convinced that Maimonides indeed denied demons in his Commentary to Avodah Zarah 4:7. However, I had a problem in that so many who knew this text did not see it as an explicit rejection. In fact, I was unaware of anyone actually citing this text to prove that Maimonides denied the existence of demons. (Only a couple of months ago did R. Chaim Rapoport call my attention to R. Eliezer Simhah Rabinowitz, She’elot u-Teshuvot ve-Hiddushei Rabbi Eliezer Simhah [Jerusalem, 1998], no. 11, who does cite this text as an explicit rejection of the existence of demons. I also recently found that R. Avraham Noah Klein, et. el., Daf al ha-Daf [Jerusalem, 2006), Pesahim 110a, quotes the work Nofet Tzufim as saying the same thing. Unfortunately, as far as I can tell, Klein doesn’t have a list of sources, so I don’t know who the author of this work is.)

Seeing that R. Zvi Yehudah Kook was quite adamant that Maimonides believed in demons,

[22] I turned to R. Shlomo Aviner, who published R. Zvi Yehudah’s work, and asked him about Maimonides’ words in his Commentary to

Avodah Zarah. Aviner convinced me that Maimonides should be understood as only denying that occult communication with demons is impossible, not the existence of demons per se. He wrote to me as follows:

הרמב”ם לא כתב שם בפירוש שאין שדים, אלא ששאלה בשדים היא הבל, וכך אנו רואים מן ההקשר שהוא מגנה שיטת שונות להשיג דברים או ידיעות, כגון “כשוף וההשבעות והמזלות הרוחניות, ודבר הכובכים והשדים והגדת עתידות ומעונן ומנחש על רוב מיניהם ושאלת המתים.”

I was still not 100 percent sure, but the fact that so many great scholars who knew the Commentary to

Avodah Zarah assumed that Maimonides indeed believed in demons gave me confidence that Aviner was correct.

[23] Even R. Kafih, in speaking of Maimonides denial of demons, does not cite the Commentary,

[24] and this sealed the matter for me. I therefore assumed that all Maimonides was denying in his Commentary to

Avodah Zarah 4:7 was the possibility of conversation with demons, and not demons

per se. (R. Aviner doesn’t speak of simple conversation, but this was my assumption.)

Following publication of the article in 2000 no one contacted me to tell me that I was incorrect in my view of Maimonides and demons. So once again I was strengthened in my assumption, and repeated my assertion in Studies in Maimonides. Not too long ago I received an e-mail from Dr. Dror Fixler. Fixler is one of the people from Yeshivat Birkat Moshe in Maaleh Adumim who is working on new editions of Maimonides’ Commentary on the Mishnah. I will return to his work in a future post when I deal with the newly published translation of the Commentary. For now, suffice it to say that he knows Arabic very well, and he asserts that there is no doubt whatsoever that in the Commentary to Avodah Zarah 4:7 Maimonides is denying the existence of demons. So this brings me back to my original assumption many years ago, that Maimonides indeed is explicit in his denial. If there are any Arabists who choose to disagree, I would love to hear it.

8. I recently sent a copy of the reprint of Kitvei R. Yehiel Yaakov Weinberg (2 vols.) to a famous and outstanding Rosh Yeshiva. In my letter to him I mentioned that the books were a donation to the yeshiva library. He wrote back to me as follows:

מאשר בתודה קבלת כתבי הגאון רבי יחיאל יעקב וויינברג זצ”ל בשני כרכים. מלאים חכמה ודעת בקיאות וחריפות ישרה, ולפעמים “הליכה בין הטיפות” מתוך חכמת חיים רבה. אולם בכרך השני יש דברים שקשה לעכל אותם, כגון לימוד זכות על מתבוללים ממש (הרצל ואחה”ע [אחד העם] בגרון ועוד) למצוא בהם “ניצוצות קדושה”. ומי שיראה יחשוב כי מותר לומר לרשע צדיק אתה. לכן כרך ב’ נשאר אצלי וכרך א’ לעיון התלמידים הי”ו.

I don’t think that any Rosh Yeshiva in a Hesder yeshiva would say that we should shield the students from the words of a great Torah scholar, but maybe I am wrong. I would be curious to hear reactions. In response to his letter, I sent this Rosh Yeshiva R. Abraham Elijah Kaplan’s essay on Herzl, to show him that Weinberg’s views in this regard were not unique.

Interestingly, in his letter to me the Rosh Yeshiva also wrote:

מה מאד נפלא מ”ש בסוף עמוד ריט על שיטת הגר”ח מבריסק לעומת שיטת הגר”א. מבחינה זו אנו לומדים בישיבה בשיטת הגר”א.

He was referring to this amazing letter from Weinberg:

קראתי את מאמרו של הגרי”ד סולובייציק על דודו הגרי”ז זצ”ל. השפה היא נהדרה ונאדרה והסגנון הוא מקסים. אבל התוכן הוא מוגזם ומופרז מאד. כך כותבים אנשים בעלי כת, כמו אנשי חב”ד ובעלי המוסר. מתוך מאמרו מתקבל הרושם כאלו התורה לא נתנה ע”י מרע”ה חלילה כי אם ע”י ר’ חיים מבריסק זצ”ל. אמת הדברים כי ר’ חיים הזרים זרם חדש של פלפול ע”ד ההגיון לישיבות. בהגיון יש לכל אדם חלק, ולפיכך יכולים כל בני הישיבה לחדש חידושים בסגנון זה, משא”כ בדרך הש”ך ורעק”א צריך להיות בקי גדול בשביל להיות קצת חריף ולכן משכל אנשי הישיבות מתאוים להיות “מחדשים” הם מעדיפים את ר’ חיים על כל הגאונים שקדמו לו. שאלתי פעם אחת את הגרי”ד בהיותו בברלין: מי גדול ממי: הגר”א מווילנא או ר’ חיים מבריסק? והוא ענני: כי בנוגע להבנה ר’ חיים גדול אף מהגר”א. אבל לא כן הדבר. הגר”א מבקש את האמת הפשוטה לאמתתה, ולא כן ר’ חיים. הגיונו וסברותי’ אינם משתלבים לא בלשון הגמ’ ולא בלשון הרמב”ם. ר’ חיים הי’ לכשלעצמו רמב”ם חדש אבל לא מפרש הרמב”ם. כך אמרתי להגאון ר’ משה ז”ל אבי’ של הגר”יד שליט”א.

9. My last two posts focused on R. Hayyim Dov Ber Gulevsky. With that in mind, I want to call everyone’s attention to a lecture by R. Aharon Rakefet in which he tells a great story that he himself witnessed, of how students in the Lakewood yeshiva were so angry at Gulevsky that they actually planned to cut his beard off. It is found

here [25] beginning at 65 minutes. The clip has an added treat as we get to hear the Indefatigable One, who mentions travelling to Brooklyn together with a certain “Maylech” in order to visit Gulevsky.

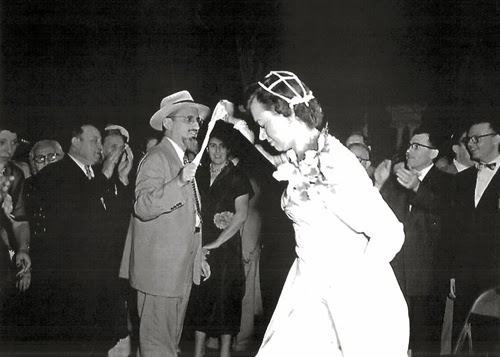

10. And finally, apropos of nothing, here is a picture that I think everyone will get a kick out of. The bride is Gladys Reiss. It shows the Rav in his hasidic side. (Thanks to David Eisen and R. Aharon Rakefet for providing the picture.)

The first is a vicious attack on the Shas MK R. Hayyim Amsellem for his authorship of a halakhic study arguing that those non-Jews who serve in the Israeli army should be converted using a less strict approach than is currently in practice. Amsellem, who is a student of R. Meir Mazuz and an outstanding talmid hakham, wrote this piece and sent it to some leading poskim to get their opinions. Amselem also discussed his approach in an interview.

כך סיפר בן אחיו של וולפסון, מר אביעזר וולפסון, תלמיד מונטרה לפנים, ואח”כ תלמיד ישיבת באר יעקב, שבה משמש המנהל רוחני מר וולבה, יליד ברלין, בנו של סופר חילוני וכופר גמור. למד בכתות הנמוכות של בית מדרשנו, ואח”כ הלך לישיבת מיר ונעשה לחניכו של ר’ ירוחם ז”ל, המשפיע המוסרי הגדול.

Here Yisrael Aryeh Leib, “the youngest brother of the Rebbe, Melech HaMoshiach, who lives forever,” is turned into a rabbi and devoted chasid. I actually contacted the person who runs the “institute” and asked him how he can so blatantly distort the historical record. Communicating with him was one of the most depressing experiences I have had in a long time. It is one thing for a person to believe foolish things, but here was a guy who had drunk an extra dose of the Kool Aid, and with whom normal modes of conversation were impossible. This is actually a good limud zekhut for him: unlike many other cases where the people distorting the historical record are intentionally creating falsehoods, in this case the distorter really believes what he is saying.

Why did R. Hayyim refuse to write responsa? Some think that his remoteness from the area of practical decisions stemmed from the fact that he belonged to the ranks of “those who fear to render decision,” being afraid of the responsibility that it entails. But this is not so. The real reason was a different one. R. Hayyim was aware that he was incapable of simply following convention and that he would be obliged, consequently, to render decisions contrary to the norm and the traditionally accepted whenever his clear intellect and fine mind would show him that the law was really otherwise than as formulated by the great codifiers. The pure conscience of a truthful man would not allow him to ignore his own opinions and submit, but he would have felt himself bound to override their decisions and this he could not bring himself to do.

אברהם ביק הכרתי בפעם הראשונה כהרה”ר של רוסי’ בא לבקר לארה”ב בשנת תשכ”ח ביזמת הרב טייץ מאליזאבעט נוא דזשערזי. וכבוד גדול עשו לו וכל גדולי ארצינו באו לבקר אותו ולחלוק לו כבוד — הוא למד בסלאבאדקא והי’ ממלא מקומו של הרב שלייפער, וניהל בחכמה ובתבונה את רבנתו ועמד על משמרתו הוא בא ביחד עם החזושל לענינגראד -השומר- בבארא-פארק עשו פאראד גדול וכל הישיבות והבית-יעקב יצאו לרחובה של עיר לחוק כבוד להעומד על משמרת היהדות ברוסי’ משם נסעו לישיבת תורה-ודעת שכל הגדולים דברו וחיזקו את הרב לעווין .משם נסעו לאליזאבעט מקום הרב טייץ — שחלקו רב בענייני יהדות רוסי’ — וגם שם הי’ פאראד גדול. והרב לעווין הי’ מאוד מרוגש .ודמעות נזלו מעיניו. נחזור לביק-הוא הי’ קאמאניסט. והי’ מכונה הרב של הקאמאניסטים. הוא כתב מאמרים בשבועון שלהם ותמיד המליץ טוב על הקאמאניסטים שהם לא רודפים את הדת. וכשהרב לעווין הי’ כאן הוא הי’ מראשי המחותנים שם. ואז דברתי איתו בפעם הראשונה. אח”כ הוא עלה לארה”ק ועבד במוסד הרב קוק ומצאתיו שם אך לא רציתי להכאיבו ולא דברנו על העבר. אז נתן לי שני ספרים א] זהרי-חמה הגהות על הזוה”ק מהיעב”ץ. ועוד ספר למוסרו לש”ב הרה”ג רמצ”א זצ”ל ביק — הוא פשוט רצה להתפייס איתו כי הם לא היו שוה בשוה-וכשהבאתי את הספרים להרב ביק דברתי איתו על אברהם ביק ואביו הרה”ג שהי’ חתן המשמרת שלום מקאדינאוו, והי’ בעל הוראה מובהק. בקיצור לאחר זמן חזר לארה”ב בגין אישתו וביתו שלא היו בקו הבריאות — הוא הי’ דמות טראגית — אביו שלחו מארה”ב ללמוד לארה”ק. אך הי’ תמיד שומר תורה ומצוות הי’ אידאליסט ולא הי’ בן יחיד במחשבתו שהקאמאניזום יציל את האנושות והיהדות .הוא לא עשה זאת מטעם כסף .הוא לא הי’ מאטראליסט. והשם הטוב יכפר בעדו.

כל שהוא מן האומות הגדורות בדרכי הדתות ושמודות בא-להות אין ספק שאף בשאין מכירו מותר וראוי.

מה שהשיג הגר”א בעניין השדים והכשפים, יש להשיב על כל דבריו: וכי מניין לו שלדברי רבנו אין מציאות לשדים ולמכשפים וכיו”ב.