A Woman's Place Is In The Home

A Woman's Place Is In The Home

The Sons of Korah declare:כָּל-כְּבוּדָּה בַת-מֶלֶךְ פְּנִימָה; מִמִּשְׁבְּצוֹת זָהָב לְבוּשָׁהּ.[1][And see here for various nineteenth and twentieth century references to our titular aphorism, and see this essay.] But is the verse indeed a normative injunction toward modesty, for women in general, or at least Jewish women in particular, as it is commonly understood? And if so, exactly what standard of behavior is being enjoined?

Cultural Norms – Twelfth Century Egypt, Twentieth Century Jerusalem and Twenty First Century Kabul

Rambam's rather extreme (by contemporary Western standards) formulation, directing a husband to "prevent his wife" from being a gadabout, and instructing him to "only allow her out around once or twice a month, as necessary", is well known: מקום שדרכן שלא תצא אשה לשוק בכפה שעל ראשה בלבד עד שיהיה עליה רדיד החופה את כל גופה כמו טלית נותן לה בכלל הכסות רדיד הפחות מכל הרדידין. ואם היה עשיר נותן לה לפי עשרו כדי שתצא בו לבית אביה או לבית האבל או לבית המשתה. לפי שכל אשה יש לה לצאת ולילך לבית אביה לבקרו ולבית האבל ולבית המשתה לגמול חסד לרעותיה או לקרובותיה כדי שיבואו הם לה. שאינה בבית הסוהר עד שלא תצא ולא תבוא. אבל גנאי הוא לאשה שתהיה יוצאה תמיד פעם בחוץ פעם ברחובות. ויש לבעל למנוע אשתו מזה ולא יניחנה לצאת אלא כמו פעם אחת בחודש או כמו פעמים בחודש לפי הצורך. שאין יופי לאשה אלא לישב בזוית ביתה שכך כתוב כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה:[2]Of course, this passage must be placed within the context of its author's milieu, a rigidly traditional Islamic society. Indeed, this attitude is still present in some modern day Muslim societies: KABUL — On a recent day when the sun was finally strong enough to dry the Afghan capital's muddy streets, Habiba Sarwe sought her husband's permission to visit a spot that her daughter and all the neighborhood wives were talking about: a park, with swings, benches, flowers and a gazebo. A park for women only. "Please, let me go," begged Sarwe, who is 44 but whose tired eyes make her look far older. "It's a good place." Her husband decided it would be okay. So that afternoon, Sarwe put on her favorite fitted gray wool suit under her shapeless, head-to-toe burqa and set out with three of her children for the dusty park on the edge of Kabul. "This is the one place that's ours," said an out-of-breath Fardia Azizmay, 19, Sarwe's older daughter, as she jumped off a swing and looked over a pile of a dozen blue burqas, tossed off by women as they entered. "For us, home is so boring. Our streets and shops are not for women. But this place is our own." The small park, protected by a half-dozen gun-toting guards, has become a favorite destination for Kabul women wanting a safe, quiet place to meet with friends, complain about their husbands, discuss their kids, line one another's eyes with black kohl or just shed their burqas and play, female activists here say. … Although women make up more than half of Afghanistan's population, fear of fundamentalist militant groups has caused them to nearly disappear from public life, especially in the rural south, where U.S.-led forces are trying to root out Taliban fighters. Some of those insurgents still pressure women to cover up and to avoid schools and workplaces, defying the Afghan constitution's guarantee of equal rights for both sexes. "I get threatening calls almost every day asking why I think I am important enough to work in an office," said Fouzia Ahmed, 25, a government secretary in Kabul. "The truth is, no women feel safe here. We are always threatened. That's why we need the eyes of the world." And the great Rav Ya'akov Yeshayah Blau gives us the not entirely dissimilar Yerushalmi perspective on women working outside the home. He takes a rather dim view of this modern trend, and maintains that the husband may not compel his wife to do so: [רוב] נשים העושות מלאכה הוא בפקידות או בהוראה, … דלא מסתבר שיוכל הבעל לכוף לאשתו לצאת לשוק בזמן שכל ההיתר לנשים לצאת לשוק אינו לפי רוח חכמים (עיין פרק ט הערה קכז מדברי הרמב"ם), ובפרט כשהרבה מלאכות כגון לעמוד בחנות או לעבוד בפקידות רחוק ממדת הצניעות, וידוע שבעוה"ר הרבה מכשולים יוצאים מזה, ובודאי שמצוה גדולה לאדם שלא יתן לאשתו להמצא בשוק כל כך, ודי לנו במה שהן מוכרחות (וזכורני שלפני עשרות שנים הרבה מנקיי הדעת בירושלים היו יוצאים בעצמם למכולת ולשאר דברים שהם צרכי הבית, וויתרו על כבודם וטרחתם משום צניעות), ועיין שו"ת רדב"ז ח"ג סימן תפ"א, ועל כן נלענ"ד שאין שום דין כפיה לאשה לצאת ולהרויח, ואדרבא, חייב למונעה מכך, ובעוה"ר נחשב הדבר כמעלה בשידוך שיש לאשה מקצוע, וכל שכן משרה שתוכל לצאת ולהרויח,[3]There are at least three Talmudic invocations of our verse as a basis for modesty, but their exact import, and even their very normativeness, are not entirely clear, as we shall see.

Talmudic Sources

Gittin

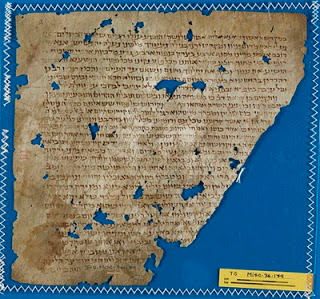

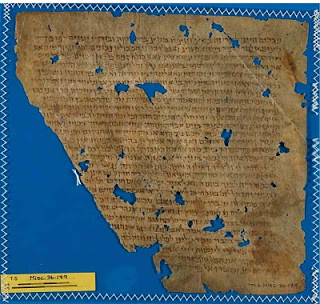

שאם ירצה שלא לזון כו': שמעת מינה יכול הרב לומר לעבד עשה עמי ואיני זנך הכא במאי עסקינן דא"ל צא מעשה ידיך למזונותיך דכוותה גבי אשה דאמר לה צאי מעשה ידיך במזונותיך אשה אמאי לא אשה בדלא ספקה עבד נמי בדלא ספיק עבדא דנהום כרסיה לא שויא למריה ולמרתיה למאי מיתבעיתא שמע עבד שגלה לערי מקלט אין רבו חייב לזונו ולא עוד אלא שמעשה ידיו לרבו ש"מ יכול הרב לומר לעבד עשה עמי ואיני זנך הכא במאי עסקינן דאמר לו צא מעשה ידיך למזונותיך אי הכי מעשה ידיו אמאי לרבו להעדפה העדפה פשיטא מהו דתימא כיון דכי לית ליה לא יהיב ליה כי אית ליה נמי לא לישקול מיניה קמ"ל ומ"ש לערי מקלט סד"א (דברים ד) וחי עביד ליה חיותא טפי קמ"ל והא מדקתני סיפא אבל אשה שגלתה לערי מקלט בעלה חייב במזונותיה מכלל דלא אמר לה דאי אמר לה בעלה אמאי חייב ומדסיפא דלא אמר לה רישא נמי דלא אמר ליה לעולם דאמר ליה ואשה בדלא ספקה והא מדקתני סיפא ואם אמר לה צאי מעשה ידיך במזונותיך רשאי מכלל דרישא דלא אמר לה ה"ק ואם מספקת ואמר לה צאי מעשה ידיך במזונותיך רשאי מספקת מאי למימרא מהו דתימא (תהילים מה) כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה קמ"ל[4]The Gemara states that we might have thought that the principle of כל כבודה prevents a husband from declaring צאי מעשי ידיך במזונותיך and thereby requiring his wife to work, but then concludes "קא משמע לן" that this is not the case. Why, indeed, is this not the case? There are various theories offered, as we shall see.

Yevamos

א"ל דואג האדומי עד שאתה משאיל עליו אם הגון הוא למלכות אם לאו שאל עליו אם ראוי לבא בקהל אם לאו מ"ט דקאתי מרות המואביה א"ל אבנר תנינא עמוני ולא עמונית מואבי ולא מואבית אלא מעתה ממזר ולא ממזרת ממזר כתיב מום זר מצרי ולא מצרית שאני הכא דמפרש טעמא דקרא (דברים כג) על אשר לא קדמו אתכם בלחם ובמים דרכו של איש לקדם ולא דרכה של אשה לקדם היה להם לקדם אנשים לקראת אנשים ונשים לקראת נשים אישתיק מיד ויאמר המלך שאל אתה בן מי זה העלם התם קרי ליה נער הכא קרי ליה עלם הכי קא אמר ליה הלכה נתעלמה ממך צא ושאל בבית המדרש שאל אמרו ליה עמוני ולא עמונית מואבי ולא מואבית אקשי להו דואג כל הני קושייתא אישתיקו בעי לאכרוזי עליה מיד (שמואל ב יז) ועמשא בן איש ושמו יתרא הישראלי אשר בא אל אביגיל בת נחש וכתיב (דברי הימים א ב) יתר הישמעאלי אמר רבא מלמד שחגר חרבו כישמעאל ואמר כל מי שאינו שומע הלכה זו ידקר בחרב כך מקובלני מבית דינו של שמואל הרמתי עמוני ולא עמונית מואבי ולא מואבית ומי מהימן והאמר רבי אבא אמר רב כל תלמיד חכם שמורה הלכה ובא אם קודם מעשה אמרה שומעין לו ואם לאו אין שומעין לו שאני הכא דהא שמואל ובית דינו קיים מכל מקום קשיא הכא תרגמו (תהילים מה) כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה במערבא אמרי ואיתימא ר' יצחק אמר קרא (בראשית יח) ויאמרו אליו איה שרה אשתך וגו'[5]

Shevuos

תניא אידך ועמדו שני האנשים בעדים הכתוב מדבר אתה אומר בעדים או אינו אלא בבעלי דינין אמרת וכי אנשים באין לדין נשים אין באות לדין ואם נפשך לומר נאמר כאן שני ונאמר להלן שני מה להלן בעדים אף כאן בעדים מאי אם נפשך לומר וכי תימא אשה לאו אורחה משום (תהילים מה) כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה נאמר כאן שני ונאמר להלן שני מה להלן בעדים אף כאן בעדים[6]

Blaming the Victim

Hasam Sofer has a remarkable responsum in which he classifies a wife who hypothetically lets herself get kidnapped as an עוברת על דת or a מורדת, since the abduction would not have occurred had she behaved properly and not wandered off alone into dangerous regions: שאלתו אודות איש א' אחר ב' שנים לנישואי אשתו ברחה מעמו ונעלמה מעין כל חי ולא מחמת קטטה כלל … רק בפתע פתאום נעלמה וזה חמש שנים לא נודע מה היה לה אחר כמה חקירות ודרישות בכל אופן האפשרי … על כן רוצה שנעיין בדינו למצוא היתר לישא אשה …תשובה. הנה אשה זו הנעלמה מעינינו יש להסתפק כמה ספיקות מה היה לה. א' אולי מתה כבר מדלא באה לביתה מקום חיותה ואם מתה הבעל מותר לישא אחרת בלי ספק:ב' אולי המירה דתה …ג' אולי נשטית מחמת שטות ברחה ולא חזרה …ד' אולי מחמת מרד ומעל ברחה ולא חזרה …ומעתה נבוא אל העיון הנה יש כאן כמה ספיקות וספק ספיקא להתיר ורק ספק א' לאסור דלמא אשתבאית … אלא שיש לומר נוקמא אחזקת חי ובחזקת צדקת שלא המירה ושלא תמרוד על בעלה בלי שום קטטה ובחזקת הגוף שלא נולד בה מום ובטלו כל הספיקות ונאמר אשתבאית בודאי ואף על גב דלכאורה שבויה על ידי אונס הוה מיעוטא דידיע הוא במדינתנו לא שכיחא שביה כלל ואפילו בשיש מלחמה בעולם ויש אלהים שופטים בארץ ואפילו באו קדרים מרחוק ונטלוה מכל מקום בעברה דרך עיירות ומקומות מדינתינו אם תזעק בחבליה יעשו לה דין ואם לא צוחה ושתקה היינו מומרת ברצון וכדאמרינן בגיטין כח: אין אנפרות בבבל ולא משכחת ליה אלא בדרך רחוקה ונפלאה וליכא אלא מיעוטא ומכל מקום נימא סמוך מיעוטא לחזקה ואיתרע ליה רובא והוה ליה פלגא ופלגא ומספיקא לא נתיר חרם רבינו גרשום:לזה נאמר שהאי ספיקא דשביה אפילו מיעוטא דמיעוטא לא הוה דודאי אם יצאה מדעת למקום יערות ושכיחא שיירות ושוללים שלא מדעת הבעל ויצאה מחזקת בנות ישראל הכשרים אשר כר' בני כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה דאף על גב דאמרינן בגיטין (יב:) [צ"ל יב.] מהו דתימא כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה קמ"ל משמע דלא אמרינן הכי ויש לומר לזה כתב רש"י כל ישראל בני מלכים הם ור"ל דהא תליא בשיטה דכל ישראל בני מלכים בשבת קכח. ולא קיימא לן כשיטה אבל כד מעיינת שפיר הא ליתא דסתמא דתלמודא דיבמות עז. קיימא לן הלכתא הך חזקה אפילו בנשי א"י הדיוטות שאינם בני מלכים כל שכן בנות ישראל הצנועות ודאמרינן בגיטין קמ"ל ר"ל דאפילו הכי מצי למימר צאי מעשי ידיך אבל האמת דכל כבודה בת מלך פנימה ודברי רש"י דתליא בשיטה צ"עולפי זה אם יצאה מדעת ונשתבאית אף על פי שעתה חזרה בה ורוצית לשוב לבעלה אלא שעומדת במאסרתה מכל מקום הוה ליה תחלתה בפשיעה ועדיין בתמרורתה עומדת ודינה כמורדת או כעוברת על דתולומר שבאו שבאים לביתה ושבוה היינו אונסא דלא שכיחא כלל שלא ידע אדם מזה דבר ולא צעקה בעיר ולא נודע מעולם שבאו שוללים לעיר ולוקחי נפשות במדינתנו ליכא ולומר שנשתטית ויצאה מדעתה והוציאה רוח רעה אל מקום לסטים ושבוה ועתה נתרפאית ועומדת בשביה אם כן היינו מיעוטא דמיעוטא דלא שכיחא כלל …[7]So Hasam Sofer, although initially suggesting that the Maskana in Gittin is that כל כבודה is not normative, ultimately concludes that it is, based on Yevamos, and explains the the former passage to mean merely that the כל כבודה imperative is not strong enough to deny the husband his right to say צאי מעשי ידיך במזונותיך. Rav Avraham Ya'akov Ha'Levi Horowitz rejects this position of Hasam Sofer, that a woman who leaves the safety of her house has necessarily acted improperly, and he argues that this is exactly the point of the Maskana in Gittin, that a woman who has a reason to leave her home, such as the need to support herself, is not violating כל כבודה:האמנם בשו"ת חת"ם סופר .. כתב דיצאה מחזקת כשרות במה שהרחיקה נדוד שאינה כבנות ישראל הכשרות דכל כבודה בת מלך פנימה לא כתב זה רק לסניף והערה בעלמא דאיך נוכל להוציאה מחזקת כשרות אולי יצאה לאיזה סבה ואפילו ביצאה לסבה לא טובה אולי אחר כך נולד לה אונס ודעתה לחזור.ובש"ס גיטין … הרי דמשום דצריכה לצאת למזונותיה לא שייך כל כבודה רק דסלקא דעתא דמשום דכל ישראל בני מלכים אפילו בכה"ג שייך כל כבודה כמו שכתב רש"י שם ולמסקנה קמ"ל דלא קיימא לן דכל ישראל בני מלכים דקיימא בשיטה בש"ס שבת (קכ"ח) ובש"ס יבמות (ע"ז) דאמרינן אפילו בעכו"ם כל כבודה כו' משום דשלא לצרכה אין דרכה לצאת ובחנם נתקשה בשו"ת חת"ם סופר שם בזה ולע"ד פשוט כמו שכתבתי: [ועיין שם עוד במה שהוכיח מעוד פוסקים שאין לדונה כמורדת בכה"ג.][8]

The Tosaphists as Pashtanim

Another application of כל כבודה appears in a number of commentaries of the Tosaphists, as well as that of the Tur, to Parshas Mishpatim, which explain the verse לא תצא כצאת העבדים, in the context of the אמה עבריה, to mean that it is inappropriate for her to work outside of her master's home, and that he may not demand that she do so: לא תצא. פירש רבי אברהם אבן עזרא ז"ל שאין האדון יכול לכופה לעשות מלאכה הצריכה לצאת חוץ, אלא בתוך הבית:[9]לא תצא כצאת העבדים. לפי פשוטו למדה תורה דרך ארץ שלא תהא יצאנית כמו העבד שרבו משגרו בשליחותו ביום ובלילה בעיר ובחוץ לעיר, וכל זה גנאי לאשה, רק שעבוד בית משום כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה, ועוד שהיא קטנה.[10]לא תצא [כצאת] העבדים. הפשט שאינו יכול להכריחה לעשות מלאכתו בחוץ כמו שהעבדים יוצאים בחוץ לשאוב מים או לטחון. או שאר מלאכות בחוץ כי אם בבית כי כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה.[11]לא תצא כצאת העבדים. … אי נמי כפשטיה, לא תצא כצאת העבדים שלא ישלחנה בחוץ לעשות לו מלאכתו אלא תשמשנו בביתו:[12]A correspondent of Rav David Menahem Manis Babad of Tarnipol was apparently bemused by this Tosaphist exegesis, presumably because the Talmud understands the verse differently, and does not mention such a restriction on the master of the אמה העבריה. Rav Babad points out that this sort of thing is common enough for "the early commentators", and adds that this rule does actually have some basis in the standard Halachah:ומה שפלא בעיניו דברי הרבי אברהם שהביא בדעת זקנים … והוא פלא בעיניו. פליאות כאלה ימצא הרבה במפרשי התורה הקדמונים. אך באמת זה אינו פלא כל כך. כיון דהוזהרנו שלא לעבוד בעבד עברי עבודת פרך ועבודת עבד. וכיון דאשה כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה. אינו יכול לעבוד בה מלאכת חוץ שלא לרצונה:[13][On the issue of medieval atalmudic exegesis, I have elsewhere noted Rav Menahem Kasher's claim that it is actually Ibn Ezra, "the chief of the Pashtanim", who frequently insists that we explain Halachic Scriptural passages only in a manner consistent with the Talmud, while "the pillars of the Halachah", i.e., the Tosaphists, are often quite flexible in their exegesis – as we see here.]Rav Yisrael of Bruna considers this Tosaphist idea to be normative Halachah, but he distinguishes between married and single women (similarly to Hizkuni above, who suggests that we may be particularly concerned about the אמה עבריה, since she is a minor):נשאלתי השוכר משרתת אשה או נערה בתולה וראובן שולח אותה על השוק ובבתי הגויים יחידית והמשרתת אומרת השכרתני לשרת כדרך המשרתות בבית ולא כדרך האנשים היוצאים בחוץ:והשבתי כן הנשים דוברות. אין ראובן יכול לכופן ליכנס יחידית בבתי הגויים ואף יש איסור בדבר משום יחוד, ואף במקום שרבים רגילים ליכנס שם נהי דאיסור ליכא מכל מקום אינו יכול לכופן, דיש נשים צנועות נוהגות בצניעות או יראות מרוב שנאה שלא יטילו עליה שם רע או כהאי גוונא.אמנם על השוק בגילוי, רגילות הנשים לילך אבל הבתולות אין דרכן לצאת לשוק ואינו יכול לכוף, ונראה לי דאף איסור יש בדבר שנאמר לא תצא כצאת העבדים. וכתב בפירוש התורה לר' יעקב בן אשר ז"ל שנקרא נזיר[14] … והתורה בבתולה קאי ובבתולה מיירי אבל נשים לא כדפרישית,אף על גב דכתיב כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה מכל מקום אשכחן בפרק קמא דגיטין דשכיח כדאמרינן מהו דתימא כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה קמ"ל, ובפרק המוצא תפלין (ערובין ק:) אמר גבי יו"ד קללות שנתקללה חוה וחבושה בבית האסורים ואידך הנך שבח הוא לה דכתיב כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה, והטעם כל ישראל בני מלכים הם. ולית הלכתא הכי. דאמרינן בפרק המקבל (בבא מציעא קיג.) אמר אביי כולהו סבירא להו כל ישראל בני מלכים הם, וכל היכא דאמר אביי הכי כולהו בחד שיטה לית הלכתא כחד מינייהו, כדפסק האשירי בכמה דוכתין, ואף על גב דבפרק ח' שרצים (שבת קכו:) פסק רב הלכתא כרשב"ג דאמר הכי מפרש התם הלכתא כוותיה ולא מטעמיה ע"ש, וכן פסק האשירי בהדיא בפרק מפנין, נאם ישראל מברונא:[15]So while the Ashkenazic Rishonim that we have seen might be construed as supporting Rav Blau's position that a husband may not compel his wife to work outside the home, Rav Yisrael of Bruna limits their rule to unmarried women.Note that many of these sources are taken from a discussion of our topic by the erudite Rav Ze'ev Wolf Leiter in his מתורתן של ראשונים.[16]Although apparently unknown to all the aforementioned Rishonim and Aharonim, there is actually Medrashic support this interpretation of the verse לא תצא כצאת העבדים – the מכילתא דרבי שמעון בן יוחאי attributes such an explanation to R. Elazar (or Eliezer):לא תצא כצאת העבדים שלא תהא נוטלת אחריו דלאים ובלוריות למרחץ דברי רבי אל<י>עזראמר לו רבי עקיבא מה אני צריך והלא כבר כבר נאסר לא תעבוד בו עבודת עבד מה תלמוד לומר לא תצא כצאת העבדים שלא שלא תהא יוצאת על השן ועל העין כעבדים …[17]Below we shall see another possible Medrashic basis for this interpretation.

Ibn Ezra

A perplexing point is the attribution of this idea to Ibn Ezra (in the first of the Tosaphist paragraphs above). As has already been noted by R. Ya'akov Gellis,[18] no such exegesis is found in our editions of Ibn Ezra. We do, however, have this not atypically cryptic passage:וכי ימכור איש. זה האיש הישראלי. ואין משפט יציאתה לחופש כזכרים. ואין צורך לפירוש הגאון לא תצא לא תשב.[19]The reference to the “explanation of the Gaon” is apparently to the first one in this passage of the commentary of רב סעדיה גאון:ואחר זה נאמר שדיבורו לא תצא כצאת העבדים סובל שני פירושים: האחד לא תדור בהיותה אצל אדוניה במצב של עבדים. כי המלה יציאה פעמים משמשת בהוראת מגורים, כמו שאמר דויד למלך מואב יצא נא אבי ואמי אתכם (שמואל-א כב:ג), וכמו שיש לפרש ויצא בן אשה ישראלית (ויקרא כד:י).הפירוש השני – שלא תצא כצאת העבדים העברים, שנאמר עליהם ובשביעית יצא (כא:ב). אבל היא דרה אצל אדוניה עד שתגדל, בין בזמן קרוב ובין בזמן רחוק.[20]This is still not very clear. R. Yehudah Leib Krinsky understands the Gaon thus:פירוש אם רעה היא בעיניו ואינו רוצה ליעדה אין ראוי שתשב בביתו להשתמשות לבד, כי אסור לו להניחה עוד ביד האדון מעת שיאמר לא חפצתי לקחתה:[21]R. Yehudah Leib Fleischer finds this explanation baseless, and offers an alternative:כתב בעל "מחוקקי יהודה" … ואין אני יודע מאין לקח את הפירוש הזה.והנה בתרגומו הערבי של רבנו סעדיה גאון ז"ל (הוצאת דירינבורג, פאריס תרנ"ג) מצאתי: “פלא תכרג כאלעביד". ותרגומו: “לא תצא כעבדים". אבל הח' המו"ל מביא שם גרסא אחרת, מדפוס קונסטיטינא (שנת ה' אלפים ש"ו ליצירה) ושם הנוסחא: “לא תקים מקאם אלעביד". ותרגומו: “לא תשב במקום העבדים". ולזה שבים דברי ראב"ע ז"ל. ומזה ראיה כי הנוסחא של דפוס קונסטיטינא הנכונה.[22]Still not very clear, but Rav Kasher understands this to mean that רב סעדיה is explaining the verse in the manner of the Tosaphists.[23] He also suggests another Medrash in support of this exegesis:[24]לא תצא כצאת העבדים, בת אחת היתה לי ומכרתיה להם [לאמה] שאין אתם מוציאין אותה אלא חבושה בארון [שנאמר] לא תצא כצאת העבדים, נהגו בה כבוד, ששביתם אותה מאצלי שנאמר עלית למרום שבית שבי וכו' (שמות רבה פ"ל ד.)מובא בילהמ"כ ישעיה דף סג. ותהלים דף קסח. ובשינויים בכד הקמח אות האמונה: וכן אמרו במדרש וכי ימכור איש את בתו לאמה לא תצא כצאת העבדים, וכי ימכור איש זה הקב"ה שנאמר ד' איש מלחמה, את בתו לאמה זו התורה שמכרה לישראל, מוציאין אותה חבושה בארון, לא תצא כצאת העבדים הזהרו בה שלא תנהגו בה מנהג בזיון והפקר, …ויש להעיר שבדברי חז"ל כאן: נהגו בה כבוד. וגירסת כד הקמח: שלא תנהגו בה מנהג בזיון והפקר, יש מקור למה שכתבו הרס"ג ושאר הראשונים בפשטא דקרא: לא תצא כצאת העבדים, כלומר שלא יכריחה לעשות מלאכתו בחוץ כמו עבדים ולא תשב במקום העבדים. ע"כ.[25]Rav Kasher also notes that Rav Avraham Menahem b. Ya'akov Rapa of Porto (who later changed his name to 'Rapaport') also offers a similar interpretation of our verse, apparently independently:לא תצא כצאת העבדים. לא תהא יצאנית לרוץ בשוק הנה והנה כדרך צאת העבדים והא צחות. וכל מקום שנאמר עבדים סתם בכנענים הכתוב מדבר שאין עבד עברי נקרא עבד סתם:[26]

Feminist and Feminine Perspectives

Rav Yehudah Herzl Henkin, always interesting on femininity and feminism, has a careful analysis of the contours of כל כבודה, of which we shall merely cite one brief excerpt, in which he argues that the loss of honor consequent to a woman's leaving her home is due to the fact that she may err and sin, and this is therefore only true in the general case, but a particular woman who can remain an אשת חיל and God-fearing is permitted to leave her home:מכאן למה שהספדתי בענין מקומה של אשה שסיימתי בו הגם שהכתוב תאר וחכמים הזהירו על סתם נשים שתשארנה בבתיהן, כל זה אמור לגבי רוב נשים, אבל יחידה שיכולה להיות גם אשת חיל ואשה יראת ד' יכולה לצאת.וכתבתי שהדבר נובע מן המציאות ומן הרגילות ומוסב על אזהרת חכמים שהאשה היוצאת מתקלקלת, וגם דברי הכתוב יש לפרש כן, שכיון שהמציאות כן ממילא כבודה של אשה היא פנימה כדי שלא תתבזה ביציאתה שהלא אם תכשל אין לה גנאי יותר מזה. …[27]We began this essay with Psalms; we give the last word to she who has been called "a psalmist for the 21st century", the incomparable אתי אנקרי, who used to insist, in the powerful, haunting, beautiful titular song of her breakout album, רואה לך בעינים, that confinement within walls and self-abnegation are just too high a price to pay, even for love: אני רואה לך בעיניים

אני רואה את הכל

היית עוטף אותי בבית וחוםרואה לך בעיניים,

רואה את הכל

היית סוגר אותי, אם היית יכול רואה לך בעיניים

שכלום לא חשוב

רק אתה, אני ואתה שוב ושוב רואה לך בעיניים

שיותר מהכל –

היית סוגר אותי, אם היית יכולהיית בונה לי קירות

היית מתקין לי מנורות

שיהיה לי אוררואה לך בעיניים,

זה כתוב בגדול

היית מרשה לי, מוחל על הכלאני רואה לך בעיניים,

רואה את הכל

היית אוהב אותי כמו שאיש לא יכולהייתי משוטטת בין הקירות

הייתי עושה בם צורות –

שיהיו לי שמייםאני רואה לך בעיניים

אני רואה את הכל

היית עוטף אותי בבית וחוםאני רואה לך בעיניים

אני רואה את הכל –

רק אותי לא רואה בתוך הכחולהלכתי לפני שעות

וטוב לי מחוץ לקירות

להתגעגע לבית[Explanation and (feminist) analysis.]I say “used to”, of course, since this is early Ankri, in her edgy, התרסה period. Current, tichel-wearing Ankri, who understands the great, paradoxical religious truth that real freedom requires discipline and subservience to a Higher law, has, indeed, explained that “it is sometimes difficult for me to to connect” to her great, early classics רואה לך בעינים and לך תתרגל איתה (although she insists that this is due to her personal maturation, rather than her religion). And musical genius that she is, she apparently occasionally manages to nevertheless perform רואה לך בעינים, while investing it with an entirely new atmosphere:"רואה לך בעיניים" כמו שלא נשמע מעולםואז אנקרי מפתיעה. היא אומרת: "לא תאמינו, אבל תאמינו", ומתחילה לנגן בגיטרה את "רואה לך בעיניים", שיר שטבוע עמוק עמוק בדי.אן.איי המוזיקלי הישראלי. גם הפעם הוא מרגש, אבל דרך הביצוע העכשווי שלו ניתן להבין את עוצמת השינוי שחל באנקרי. משיר שתמיד היה נשמע כעוס וכואב יוצאת פתאום אתי אנקרי אחרת – מפויסת, שלמה, שלווה, במשמעות הפוכה לביצוע המקורי.[Note: this essay has its roots in a discussion that occurred on the Areivim and Avodah mailing lists; see this אישים ושיטות post, and my comment thereto.][1] תהילים מה:יד – קשר[2] משנה תורה – יד החזקה אישות יג:יא – קשר[3] פתחי חושן ירושה ואישות פרק י' הערה ט' ד"ה ומהו שיעור המלאכות, ועיין לעיל שם הערה ג'[4] גיטין יב. – קשר[5] יבמות עו: – עז. – קשר[6] שבועות ל. – קשר[7] שו"ת חת"ם סופר אה"ע חלק ב' סימן צ"ט – קשר[8] שו"ת צור יעקב סימן ע"ה – קשר[9] דעת זקנים מבעלי התוספות שמות כא:ז, ועיין תוספות השלם (גליס) אותיות ט וי"ט[10] פירוש החזקוני שם[11] פירוש התוספות, נדפס בספר הדר זקנים (ליוורנו ת"ר), והובא בחומש אוצר הראשונים, שם – קשר[12] פירוש על התורה מרבינו יעקב בן כבוד מרנא ורבנא רבינו הרא"ש זלה"ה (הנובר תקצ"ט), שם – קשר [עמוד 19][13] שו"ת חבצלת השרון, תנינא סימן י' – קשר[14] איני יודע פירוש מילים אלו[15] שו"ת מהר"י ברונא, סימן רמ"ב – קשר[16] גיטין שם – קשר[17] מכילתא דרבי שמעון בן יוחאי (מהדורת אפשטיין), שם, עמוד 165 – קשר, הובא בתורה שלמה אות קס"ג[18] תוספות השלם, שם, עמוד קע"ג. I am indebted to Andy for bringing this to my attention.[19] אבן עזרא (מהדורת וייזר), פירוש הקצר שם, עמוד רצא[20] פירושי רב סעדיה גאון לספר שמות (מהדורת רצהבי), שם, עמוד ק"י[21] מחוקקי יהודה, שם, יהל אור אות רי"ח – קשר[22] משנה לעזרא, שם, עמוד 161 – קשר[23] תורה שלמה, שם, אות קס"ג[24] I do not understand why Rav Kasher adduces this Medrash, since he himself has earlier cited the מכילתא דרשב"י which would seem to be much more directly supportive of the Tosaphist position.[25] שם, אות קס"ו[26] מנחה בלולה (ווירונה תשנ"ד), שם – קשר[27] שו"ת בני בנים, חלק א' סימן מ' ד"ה מכאן למה שהספדתי – קשר