Hadaran: Who is going down to the pit of destruction?

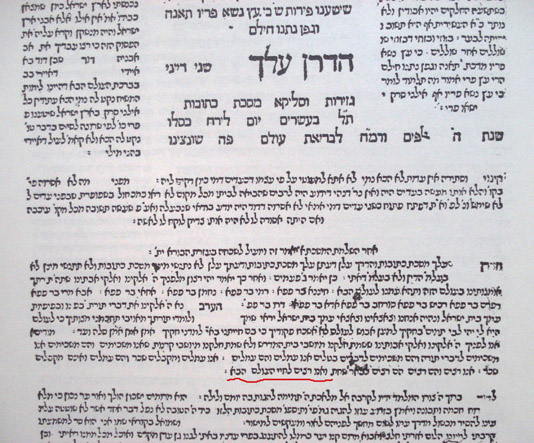

In his Sefer Divrei Torah (Mahadura 5)the Munkasczer rebbe, an avid bibliophile, indicates that the verse should be omitted.

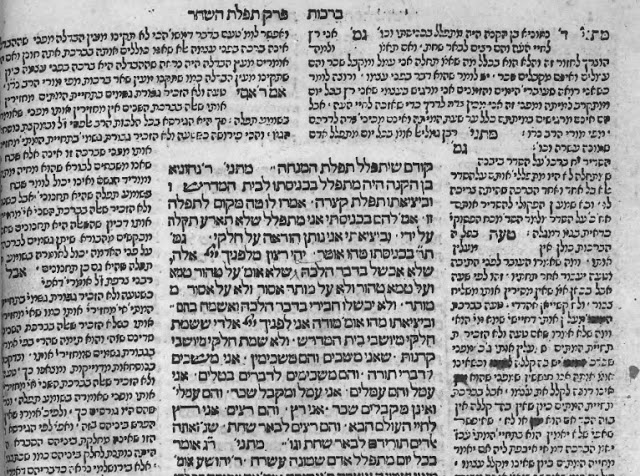

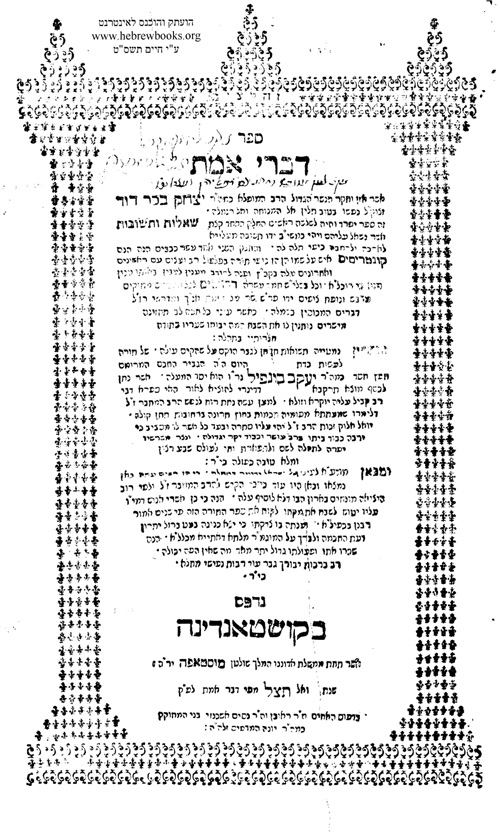

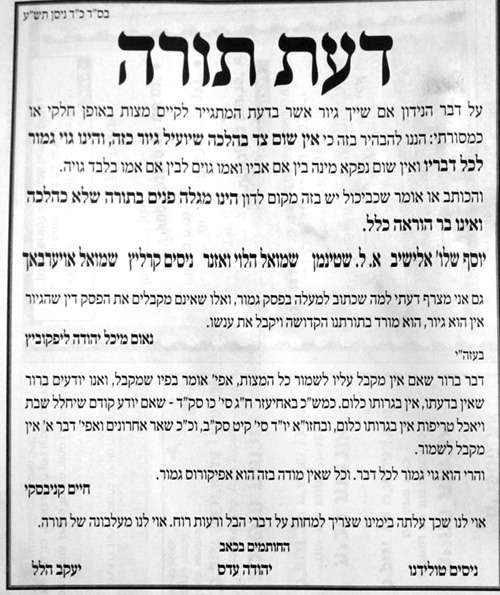

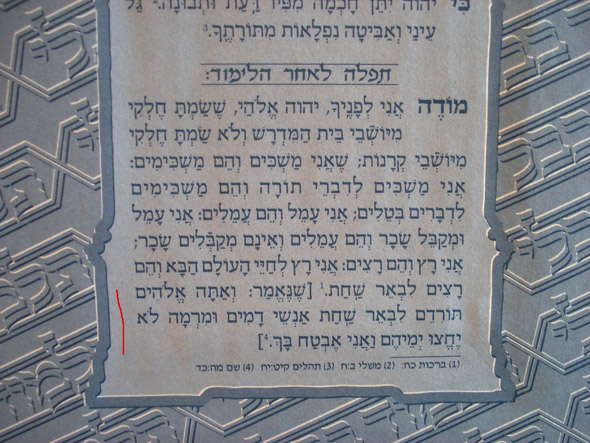

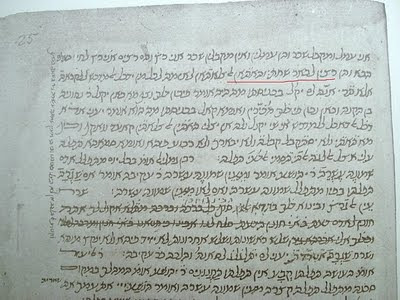

The verse only appears in one known halachic source: Halachot of Rif (Rabbi Yitzhak Alfasi). See below (1st edition, Constantinople 1509):

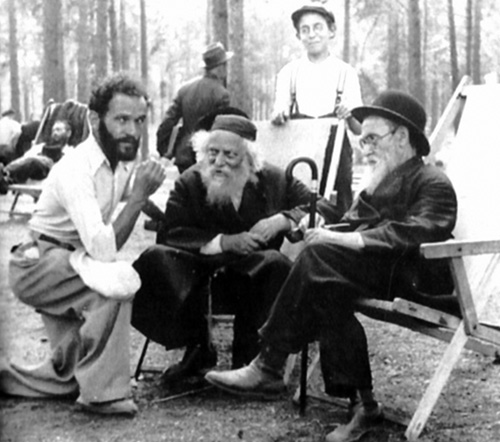

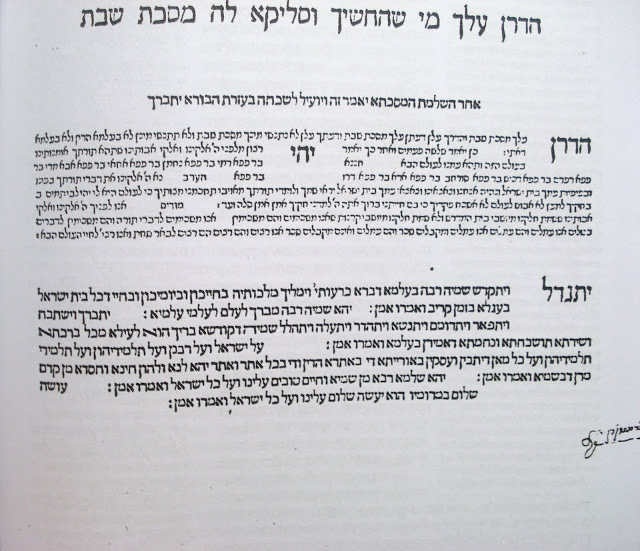

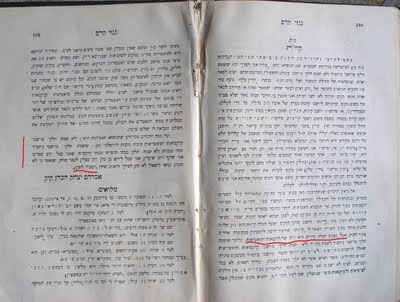

We are not the first ones to find the prayer in the hadaran to be overly contentious. No less an illuminary than Rav Avraham Yitzchak Kook, OBM, the first chief Rabbi of Israel, was deeply disturbed by this prayer’s tone. Yoshvei Kranos are today’s ba’alei batim. They keep mitzvos and give tsdakah. The takanah to read the torah on Monday and Thursday is for them, so they should not go too long without hearing words of torah. It goes completely against the grain of Hazal to curse them! In fact, even without the verse, why should they be punished at all?

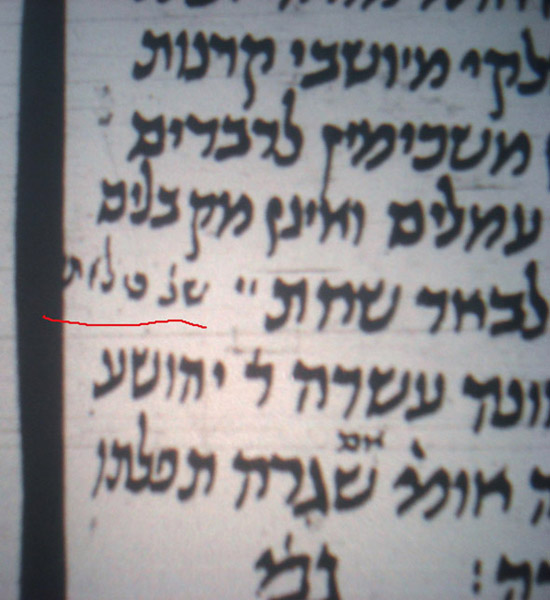

Here are Rav Kook’s words (you may click this image to read a larger copy):

Many thanks to Moshe Bloi, Ezra Chwat and Shamma Friedman. All errors are, of course, mine.

Note: This article is based on one which originally ran in Kolmos of Mishpacha magazine and they take no responsibility for the content here. You can read the original article here.

UPDATE 8/18/2011: A song has recently been composed as a result of this article and discussions surrounding it’s Hebrew and English versions. The song lyrics consist of only the two verses and highlights the contrast between them musically.

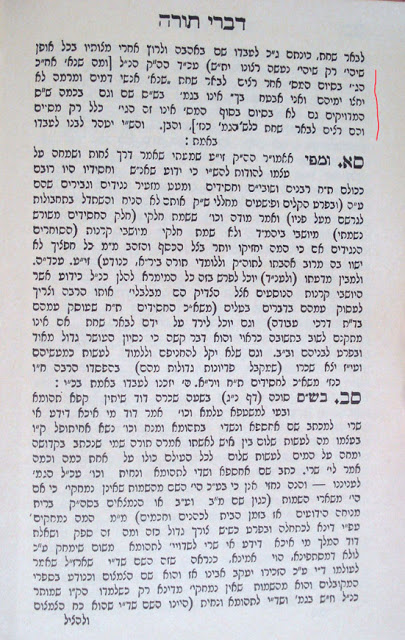

Here the composer explains the composition in Hebrew and provides a link to the previous Hebrew discussion which inspired it:

[3] Note that the order in the prayer is switched around, probably in order to end on an upbeat, good note.

Shaul Magid – ‘Uman, Uman Rosh ha-Shana’: R. Nahman’s Grave as Erez Yisrael

There is a Talmudic adage that teaches: “evil-doers are dead even when they are alive; righteous individuals are alive even when they are dead.” Setting aside the obvious metaphoric intent of this comment, in the case of Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav who left this world on the intermediate days of Sukkot 200 years ago, this teaching has a more literal flavor. Nahman was one the few zaddikim who meticulously planned his death – suffering for years with tuberculosis – advising his disciples how to behave after his passing and urging them that if they visit his grave he will “pull them up from the netherworld by their sidelocks.” Almost immediately after his untimely death at the age of 39 and burial in Uman in the Ukraine, his gravesite became a place of pilgrimage for Bratslaver Hasidim, often under harsh weather conditions, vehement and often violent harassment by other Hasidic sects, and later harsher political realities. There were times when there was barely a minyan at his gravesite on Rosh ha-Shana, the most auspicious days of pilgrimage. Today there are close to 20,000 souls, religious, secular, men, women and children who flock to Uman on Rosh ha-Shana to pray at the grave of this enigmatic Hasidic master. The Ukrainian government recently refurbished an old military airstrip in Uman to accommodate the jumbo jets that arrive from Israel, Europe, and the US, and the city magistrate built hotels to accommodate pilgrims just for this two-day festival. Tonight I want to explore this seemingly odd phenomenon of Nahman’s grave, paying close attention to the strange but not unprecedented notion that this gravesite is considered, for Bratslaver Hasidim, not only a holy place but “Erez Yisrael.” Grave veneration and its significance in the larger schema of devotional life is shared by many religious traditions including Judaism. The Torah, beginning with the descriptions and the importance of the gravesites of the biblical characters in Genesis, culminating with the ambivalence about knowing the site of Moses’ grave at the end of Deuteronomy, emphasizes the sanctity of the grave as sacred space. The importance of the gravesite was not adopted by post-biblical Judaism as merely a theoretical notion but had practical implications as well. Rabbinic tradition understood the graveyard as a place of meeting between the living and the dead, thus serving as a place imbued with a highly charged spiritual energy where penitential prayers could more easily be efficacious. The rabbis believed both in the sacredness of the place (i.e., the graveyard) coupled with the more general notion (not limited to the space of the graveyard) that the righteous in heaven could serve as intermediaries and petition the celestial court for mercy. Maimonides codifies as law that if one wishes to ask forgiveness before Yom Kippur from someone who has died he or she should visit their grave and ask forgiveness there. The medieval kabbalistic tradition, from the Zohar through Lurianic Kabbalah in the sixteenth century, developed this rabbinic notion of the graveyard as a highly charged spiritual place to a holy site for pilgrimage, whereby the journey to the grave of the righteous was viewed as a holy ascent (e.g. Zohar). The graves of the righteous became the place where one could actually absorb the spiritual energy of the departed Zaddik by means of prostrating oneself on the grave. The Lurianic contribution to the development of this idea suggests that the grave of the righteous is a place of transparency between this world and the next whereby the living are transformed and purified by embodying the souls of the dead through bodily prostration on the grave. The earlier rabbinic and zoharic notion that the grave is the place where the dead interact with the living and prayers are more readily heard via the mediation of the parted one becomes, for Luria, something far more profound. The grave becomes the place where the worshipper is purified through contact with the dead/living Zaddik and transformed by embodying the soul of the Zaddik which hovers above the grave itself, freed from its corporeality of the physical body. This phenomenon of “soul hovering” is limited to the righteous ones who, having achieved otherworldliness in this life, are able to maintain a connection to this world after death. (This may be his reading of the talmudic passage cited above that the righteous are alive even after death.) The transparency model of the grave initially suggested by the rabbis becomes, for Luria, the place where the dead, as it were, embody the living and thus purify the living soul from sin and impurity. The pilgrimage model of the Zohar coupled with the transformative model in Luria serve as the foundation for R. Nahman of Bratslav’s theory of his grave as the transparent creative center, the place which holds the power of creation and the place from which redemption will ensue. Although grave veneration had already taken on a devotional component in the Zohar and more prominently in Luria’s re-construction of Judaism, the Bratslav tradition is unique in that its entire Hasidic ideology is centered around the grave of their venerated master Nahman of Bratslav. Although this idea only bears fruit in post-Nahman Bratslav literature, beginning with the first Rosh Ha-Shana after his death, it’s importance begins years before, soon after Nahman’s return from his journey to Erez Yisrael in 1798-99. It was only then that he began to speak simultaneously about his impending death and the importance of visiting his grave, all within the larger schema of the transformative experience of his journey to the Holy Land. His death, place of burial and the unique character of his grave become increasingly prominent in his teachings as his tuberculosis worsened and his death drew near. One familiar with zoharic literature will immediately notice that Nahman’s pre-occupation with the importance of his own death reflects the discourse of the Idrot, the opaque yet highly influential sections of the Zohar which focus on R. Shimon bar Yohai’s death at the hands of the Romans. It is somewhat surprising that post-Nahman Bratslav literature never makes mention of this highly charged and seemingly obvious connection. Perhaps it is due in part to the Bratslav position, inspired by Nahman himself, that he is an unprecedented figure in Jewish history, one who owes allegiance to no one. This is exhibited by the almost complete absence of any reference in his collected teachings, Likkutei MoHaRan, to any other Hasidic master, including his great-grandfather, the Baal Shem Tov. In any event, the connection between Nahman’s pre-occupation with his death and the discourse of the death of R. Shimon bar Yohai in the Zohar should not be underestimated precisely because the messianic impulse of the Zohar (Idrot), a phenomenon already documented by Yehudah Liebes, is alive in Nahman’s discussion as well. It is therefore curious that Liebes who does draw our attention to the messianic underpinnings of Nahman’s Tikkun Ha-Kelali (the Ten Psalms Nahman directed his students to recite daily as a tikun for sin) and its connection to Sabbateanism, never develops the extent to which the recitation of the prescribed Psalms which comprise Tikkun Ha-Kelali are meant to be recited at Nahman’s grave as part of the ritual of purification in conjunction with visiting his burial place (known as his “zion”). In my view this is of utmost importance in the Bratslav tradition precisely because Nahman’s grave represents a manifestation of the Holy Land, a place even more transparent than the land itself, which is quite peculiar and serves as a the basis of his messianic vision. My claim here is that Nahman’s grave as the centerpiece of the Bratslaver’s devotion life and Erez Yisrael as the center of Nahman’s spiritual life are inextricably intertwined. Although the correlation between his trip to Erez Yisrael in his development as a Zaddik has received close scholarly attention – a more nuanced understanding of Nahman’s relationship to Erez Yisrael, his vocation as an unprecedented Zaddik coupled with his messianic strivings, cannot be achieved without understanding the significance of his grave in his own mind as well as in the larger trajectory of Bratslav Hasidism. In fact, it is my belief that the significance of his grave as Erez Yisrael serves as the cornerstone of his entire ideational edifice and contribution to Jewish thought. As I mentioned above, earlier kabbalistic sources (rooted in more opaque rabbinic comments on the matter) present the grave as the transparent space between this world and the next, the place where one can embody the soul of the dead precisely because the soul is no longer confined by the physicality of the body. Nahman universalizes this idea by suggesting that the grave of the Zaddik as a transparent place also holds the potential to draw unmitigated mercy into the world, thus bridging the distance between exile and redemption. This is based on his utilization of the kabbalistic mapping of the emanation of divine effluence into the world as it relates to the death of a righteousness individual. His assumption is that death is the liberation from the confines of the Intellect or worldliness, and entry into the realm of Pure Spirit. Yet the deaths of all individuals are not identical. It is only the Zaddik who can draw this realm of Pure Spirit into the world, because the Zaddik, by means of what he has achieved in this world, easily traverses between this world and the next, even during his life. The transparency of the gravesite of the Zaddik is already forged by the devotion of the Zaddik during his life. Although others may benefit from the glory of the next world, their knowledge of and communication with this world ceases once they pass through the opaque and final barrier of death. But Nahman maintained that life and death for the Zaddik are not mutually exclusive categories. This attitude is exhibited in Nahman’s sarcastic remarks about the simpletons who he witnessed visiting the graves of their ancestors in Uman, crying and begging for mercy as if their ancestors could hear them. Only the Zaddik can hear prayer from the world beyond, Nahman comments, because the Zaddik has achieved the next world while still alive in this world. Hence, he describes his journey from life to death as “going from one room to the next.” This transparent space which is embodied in the grave of the Zaddik is also the creation point, the place where the finite and the infinite meet. (Likkutei MoHaRan 48). He develops this midrashic idea by taking the infinite-finite modality of creation and presenting it within the framework of creation and redemption. The sacredness of space, which is determined by its transparency, is simultaneously the place of creation and redemption because it is the place where Wisdom (Hokhma) is overcome by the higher dimension of Spirit (Keter), a movement whereby the finite is overcome by the infinite. This movement is only achieved and maintained by the true Zaddik (only Nahman!) who embodies this pure spirit during his lifetime. Nahman claimed to have achieved this state of purity as the result of his trip to Erez Yisrael in 1798. Thus, upon his return from Erez Yisrael he describes his experience as one of achieving “expanded consciousness’ (mohin d’gadlut), which is defined sometimes as “utter simplicity” (p’shitut) and complete loss (read: overcoming) of knowledge. This dimension of “not-knowing” always holds a higher and more refined status than “knowing” in Nahman’s highly anti-rationalist orientation. This new level of consciousness achieved during his brief but cathartic encounter with the Holy Land resulted in his utter abandonment of anything he had taught prior to his trip, which he determined was the product of Hokhma, or knowledge, as opposed to Keter, or Pure Spirit. Most of his teachings collected in Likkutei MoHaRan were delivered in the decade after his return from Erez Yisrael in 1799 until his death in 1810 (he remarked to his disciple R. Nathan that all his teaching from before his journey to the Holy land are null and void). The elevation of the Intellect to Spirit, which is nothing less than the overcoming of humanness and exile, was thus achieved by Nahman, in his own estimation, during the last decade of his life. This transformative experience is not attained merely by his presence in the Land, although the physical Land does play a central role. (e.g. Shivhei Ha-Ran where he stresses the literalness what he means by the Holy Land, “the houses” etc.). Such an achievement is the result, rather, of absorbing the Land (not merely encountering it), of becoming a human embodiment of Erez Yisrael thus enabling him to transport its sanctity beyond its physical boarders. This transference of sanctity from the Land to an individual is only true of the Zaddik who, as a pure vessel, can receive, be transformed and integrate that sanctity into his life. Much has been made of Nahman’s distinction between the physical Land of Israel and the “aspect” (behina) of Erez Yisrael, a spiritualized idea which may be related to but not identical with the Land itself. Discussions by Martin Buber and Eliezer Schweid about Nahman as a proto-Zionist rest on these slippery distinctions in his writings. I would suggest that these two formulations in Nahman’s writings are hinged together by means of the Zaddik in general and the Zaddik’s grave in particular. That is, the aspect of Erez Yisrael (behinat Erez Yisrael) arises when the Zaddik visits the physical Land, absorbs it, and transports its spiritual essence outside its borders. His teaching becomes the transmission of Keter (Spirit) rather than Hokhma (Knowledge), the result of his embodiment of Pure Spirit drawn from the Holy Land thus overcoming the more human and exilic dimension of Hokhma. However, this “new” Torah (his teachings after he returns from Erez Yisrael), which for Nahman is the true Torat Erez Yisrael – an idea originating in rabbinic literature but completely transformed in Nahman’s imagination, uprooted from any territorial limitations – is a necessary but not sufficient condition to complete the (redemptive) process from Erez Yisrael to behinat Erez Yisrael. His torah only prepares his listeners for what is to come. The completion of this transformative messianic process occurs via the death and burial of the unique Zaddik in the earth of Huz l’Aretz and the encounter of his disciples with the grave whereby they too absorb elements of this sanctity. His death and burial sanctifies the land outside of Erez Yisrael, widening the boarders of sanctity from the sacred place of Erez Yisrael to the new transparent place, which is the grave of the Zaddik. The spiritualization of the land (behinat Erez Yisrael) carries messianic implications which lie at the heart of Nahman’s discussion about his grave, accompanied by the liturgical formula of the Ten Psalms (Tikkun Ha-Kelali) which were initially given to be recited at his gravesite. (Liebes) There is an important distinction implicit in Nahman’s teaching between the Land itself and the aspect of the Land (behinat Erez Yisrael) which arises via the Zaddik’s interaction with it. When the true Zaddik visits Erez Yisrael, absorbs it and gives rise to the spiritualized aspect of Erez Yisrael (behinat Erez Yisrael) activating a spatial transparency, which the Land itself cannot produce without the aid of the Zaddik’s visit. In some sense, his visit to Erez Yisrael and his subsequent return to Huz l’Aretz (a component of great significance which we will see below) transforms not only the Diaspora, via his grave, but transforms the Land itself by released the spiritualized energy contained within it. The Land itself is thus brought to life, as it were, by the Zaddik’s visit, and it is the Zaddik who takes the sanctity of the Land beyond its borders. The notion that in the messianic era the entire world will become Erez Yisrael has precedent in medieval kabbalistic literature (e.g. Avraham bar Hiyya’s Megilat ha-Megaleh). Another important component in his journey to Erez Yisrael and subsequent return to the Ukraine is his acquisition of “Torat Erez Yisrael” which serves as the arc between his visit to the Land and his subsequent death and burial. In various places Nahman is said to have made the provocative statement that he had achieved Torat Avot, (lit. the Torah of the Patriarchs) a curious term which he never explains. Various accounts reflecting his new achievement resulting from his trip, one of which takes place on a Turkish warship just before Passover on which he and a disciple were traveling from Acre to Turkey. Being erev Pesah, Nahman was unsure whether they would reach port in time for the holiday and thus unsure whether they would be able to fulfill the mitzvah of eating matza. Nahman asserted that he was now (in the wake of his trip to Erez Yisrael), if necessary, able to fulfill mitzvot in a purely spiritual manner, that is, without physically performing the mitzvah itself. Although we are told they did arrive in time for the festival, this assertion may illuminate his opaque statements about achieving Torat Avot. Commenting on the talmudic claim that the Patriarch’s fulfilled the entire Torah, even erev tavshilin, a rabbinic decree utilizing a legalistic loophole permitting one to cook on Yom Tov for the upcoming Shabbat, many Hasidic texts speak of the a spiritualized Torah before Sinai whereby the biblical characters in Genesis (specifically Abraham) were able to fulfill the entire Torah because they were evolved enough to intuit divine will without the commandments. It is my feeling that this was the ideational foundation of Nahman’s statement on the Turkish warship mentioned above. His assertion about Torat Avot is a formulation of his more developed notion of Torat Erez Yisrael. He held that his becoming Erez Yisrael via his journey resulted in the acquisition of Torat Erez Yisrael which is the pre-Sinaitic Pure Spirit of Torat Avot, an embodiment of the sephirah Keter. The fact that (1) the Patriarchs largely dwelled in Erez Yisrael, (2) revelation was in Huz l’Arez, resulting in the suggestive dichotomy between Sinai and Zion, and (3) Moshe, the arbiter of Torah, never entered the Land of Israel, all play an important role in Nahman’s imaginative thinking. Torat Moshe or revelation as the Torah of Hokhma verses Torat Elohim, or Torat Erez Yisrael, which is the Torah of Spirit, is an idea implicit in R. Nahman’s discourse developed in a different manner by his great grandfather the Baal Shem Tov and later in Polish Hasidism, which was significantly influenced by Nahman’s Likkutei MoHaRan. His suggestion that his encounter with Erez Yisrael unlocked the spiritualized Torat Avot, which itself may be yet another layer of his more ambiguous behinat Erez Yisrael, is an idea which had far reaching influence. We find similar ideas in Zionist thinkers such as Abraham Isaac Ha-Kohen Kook and Aaron David Gordon, both of whom were influenced by the teachings of Nahman. Yet I maintain that these readers of Nahman mis-read his idea of Erez Yisrael precisely because they are not cognizant of the fact that this “new” component of sanctity whereby the Zaddik becomes the Land, necessitates returning to Huz l’Aretz to complete the messianic process. Hence his journey home, his subsequent teaching and his death and burial all congeal to push the impending messianic era toward fruition. Nahman’s view of himself as the true Zaddik, one who has no authoritative spiritual lineage precisely because he is sui generis, lies at the foundation of his thought. This claim was not only true of how he viewed himself vis-à-vis his contemporaries but more importantly his position as a figure in widest span of Jewish history. His uniqueness becomes manifest through his unprecedented journey to the Holy Land, a trip which he held introduced a new dimension into the exilic world. What I am about to suggest has no source in Bratslav literature and thus may be construed as speculative or, at best, midrashic in nature. However, it illuminates the extent to which his grave became the centerpiece of his entire life, the culmination of his journey, and the prism through which his messianic vocation must be seen. Nahman makes various comments throughout his writings about what he determined as his spiritual lineage, beginning with Moses, R. Shimon bar Yohai, R. Isaac Luria ending with his grandfather, the Baal Shem Tov. Yet Nahman maintains in subtle and not-so-subtle ways that he transcends them all, including Moses. Moses’ grave is unknown and will remain so. R. Shimon bar Yohai and Luria’s graves are both in Erez Yisrael. The grave of the Baal Shem Tov is in Hutz l’Aretz and, as opposed to Moses’ grave, became a shrine which Nahman visited many times in his youth. Although the graves of these masters were held in high esteem by Jewish pilgrims, according to the Bratslav tradition, none contained the sanctity and redemptive quality of Nahman’s grave in Uman. The reason for this, I believe, lies in Nahman’s journey to Erez Yisrael, the completion of which was his return and subsequent death in Huz l’Aretz. Moshe is born and dies in Huz l’Aretz, never entering the Land. R. Shimon bar Yohai resides in Erez Yisrael his entire life and is buried there. Luria is born in Erez Yisrael, spends most of his life in Egypt and returns to Erez Yisrael where he dies and is buried in 1570. The Baal Shem Tov is born in Hutz l’Aretz and attempts unsuccessfully to reach Erez Yisrael, dying in Mezybuzh. Of the four, only R. Nahman is raised in Hutz l’Aretz, reaches Erez Yisrael and successfully returns to Hutz l’Atretz to spread Torat Erez Yisrael and is subsequently buried in Uman. This cycle of immigration and emigration (aliya and yerida) is the focal point of Nahman’s life and, in my mind, is the foundation of his messianism. His journey is reminiscent of Rabbi Akiba’s to Pardes, to experience the sanctity of God’s glory and emerge unscathed. In Nahman’s mind, however, his return carries far greater weight. Whereas we are not told of any significant change in R. Akiba’s torah after his ascent into Pardes, Nahman’s journey resulted in the acquisition of Torat Erez Yisrael, an apprehension of the pre-Sinaitic Torat Avot, the rise of the spiritualized nature of Erez Yisrael s behinat Erez Yisrael and began the widening of the boarders of Erez Yisrael in the sanctification of his burial place in Uman. In the Bratslav tradition, conventional notions of grave veneration have been transformed, making the grave the transparent place where new light brightens the world, new Torah descends from behind the curtain of Sinai and the Zaddik as axis mundi absorbs and transforms the sanctity of the Land. In sum, I would suggest that the Bratslav pilgrimage tradition has at least three components that are unique to the phenomena of religious pilgrimage in general. First, the devotee’s pilgrimage to Nahman’s grave is predicated on Nahman’s own pilgrimage to Erez Yisrael. That is, one could ask, given Nahman’s insinuation that his trip gave rise to the importance of visiting his grave, why isn’t a trip to Erez Yisrael proper preferred to a pilgrimage to his grave. A preliminary answer may be that Nahman held that one who is not a Zaddik cannot achieve in Erez Yisrael what he achieved. A true journey to Erez Yisrael, one which could in some sense replicate Nahman’s journey, can only be accomplished by visiting the Erez Yisrael of his grave, the source of behinat Erez Yisrael. In fact, Nahman was adamant about not being buried in Erez Yisrael, fearing that his disciples wouldn’t visit his grave and thus the efficacy of his journey and return would be for naught. For him, the pilgrimage to his grave in Hutz L’Aretz is more important than the pilgrimage to the Land itself. His journey to the Land, resulting in his absorption and embodiment of Erez Yisrael, had at least two consequences that make his grave more prominent than the Land itself. First, it widened the boundaries of the Holy Land, a redemptive sign born out of previous kabbalistic literature that the messianic age will result in widening the boundaries of Erez Yisrael. Second, it activated the source of the sanctity of Erez Yisrael, behinat Erez Yisrael, a spiritualization of the Land which enabled the Land itself to fulfill its holy destiny. Finally, his grave became a representation of his messianic vocation. As both Art Green and Yehudah Liebes have noted, Nahman’s messianic vision was not centered on being the Messiah but, closer to the model of R. Shimon bar Yohai in the Zohar (Idrot), as forging the path toward revealing the Messiah. Just as the Zohar was viewed as the doctrine that unlocked the esoteric nature of Torah, Nahman’s grave was envisioned by him and then his disciples as unlocking the esoteric power of Erez Yisrael. Finally, his journey and subsequent teaching enabled the Land to speak, as it were, as his teachings reflected the true Torat Erez Yisrael, the Torah rooted in the Pure Spirit of Keter which is revives the pre-Sinai Torah of the Patriarchs. It may seem odd today that thousands of Bratslaver Hasidim leave their families behind and travel from Israel to the small city of Uman in the Ukraine to celebrate Rosh Ha-Shana. One would think Israel and not the Diaspora should be the spiritual destination of Jews during this time of year. But when asked about his impending trip from Israel to Uman for Rosh ha-Shana, the Jerusalemite Bratslav manhig Schmuel Shapiro obliquely responded, “From Erez Yisrael to Erez Yisrael.” I have tried here to shed some light on those five words.

מנהג אכילת ה’סימנים’ בליל ראש השנה וטעמיו

New Sefer Announcement

I should mention that in the latest issue of Kovetz Eitz Chaim there appears an article under my name about Ledovid in Elul. [The version in this new sefer of mine has more than double the material than the article]. I was asked by an editor of this journal for this article. I was happy to give it to them although they have their methods of what to include and what not to include as has been demonstrated in the past on this Blog. However I was very disappointed to see that the besides omitting some of the sources and names they have changed my article with a completely different outcome than that I had written.

The second chapter deals with Efer Parah (ashes of the Red Heifer) and when exactly did we lose it. A version of this chapter appeared in my sefer Bein Kesseh Le-assur (of which copies are still available for purchase) and on the blog. In this new sefer many additions were added. Among topics discussed in this chapter are lengthy discussion of the famous Berita De-mesctas Niddah and if R. Eliezer Kaliar was a Tanna.

The third chapter revolves around the Sefer Hapeulot of R. Chaim Vital. This chapter has twenty sub-chapters based in part on my post on the blog but full of new material. Amongst the topics dealt with are Alchemy, Shelios Chalom, Goralos, automatic writing, ghosts and much much more.

The fourth chapter is about the Maggid of the Beis Yosef. This chapter consists of seven sub chapters focusing on the Poskim and how they viewed this work. I begin with as an example the words of the Maggid to the Beis Yosef (“BY”) not to eat meat on Rosh Hashana (“RH”). I deal with how the Maggid could have forgotten a Mishna which says one is supposed to eat meat on RH and a gereal discussion how a Maggid works in this regard. I have a section dealing with the various sources about eating meat on RH. Another section deals with who was the Maggid talking to just the BY or to everyone. The BY never quotes the Maggid but other poskim do bring him. I deal with the topic of Torah lav ba-shmayim in regard to this. Another section deals with the Rambam forgetting sources. The last section deals with the famous words which the Maggid told the BY many times that he would die Al Kidush Hashem via burning and we know he did not.

This sefer is available for purchase in the US by Biegliesin in NY, in Lakewood at Judaica Plaza and in Mosey at Tuvias’s. In Jerusalem it is available at Girsa, Otzar Haseforim and next to the Mir. It is also available for purchase from the author and can be shipped worldwide. A PDF of the table of contents and index are available, for more information contact me at eliezerbrodt@gmail.com.

Some More Assorted Comments, part 1

ASK [Atlanta Scholars Kollel], however, has demonstrated a willingness to meet its constituency on its own terms by running a biweekly introductory prayer service in one of Atlanta’s largest Reform houses of worship, Temple Sinai of Sandy Springs. To be sure, the meetings take place in a social hall rather than in the synagogue sanctuary, but this is a clear departure from the guidelines set down by Feinstein. Similarly, members of the Phoenix Community Kollel have taught classes at the community sponsored Hebrew High that is housed at the Reform Temple Chai. . . . [T]he head of Pittsburgh’s Kollel Jewish Learning Center, Rabbi Aaron Kagan, meets on a regular basis with his local rabbinic colleagues from Reform and Conservative synagogues to study Torah together. . . . Based in Palo Alto, California, the Jewish Study Network—one of the most dynamic and rapidly expanding of these kiruv kollels—does not limit its interdenominational contacts to private study. Its fellows work together with Conservative and Reform representatives to create new Jewish learning initiatives throughout the Bay Area and to offer their own programming in non-Orthodox synagogues. Rabbi Joey Felsen, head of the Jewish Study Network and a veteran of five years of full-time Torah study at Jerusalem’s venerable Mir yeshivah, made clear that he was not opposed to presenting Torah lectures in a non-Orthodox synagogue sanctuary, although he preferred to teach in the social hall. Indeed, according to Rabbi Yerachmiel Fried, leader of the highly successful Dallas Area Torah Association (DATA) Kollel and a well-respected halakhist, insofar as Jewish religious institutions were concerned the only boundary that remained hermetically sealed was his unwillingness to teach in a gay synagogue. . . .

Needless to say, the woman was shocked, and all who are interested can consult the book to see how the Maggid convinced her that despite the man’s unusual demand, she should nevertheless agree to the match.

Among other sources R. M. Shapiro finds a basis for permitting women’s aliyyot outside the synagogue in an anonymous opinion quoted in Sefer ha-Batim. . . . Indeed, here we find a clear statement that one opinion considers women’s aliyyot problematic only in the context of public reading in a synagogue, whereas when a group prays at home, women may receive aliyyot.

The proper role of women in the synagogue is an issue that Modern Orthodoxy has been struggling with for over forty years. While everyone agrees that halakhah has to guide all changes in synagogue practice, women’s changing self-perception and religious sentiment must be central to any discussion of synagogue life. In recent decades many avenues for Modern Orthodox women have been opened, and have achieved widespread communal support. Yet when it comes to a fuller participation in public prayer and reading of the Torah great conflict has ensued. In this provocative book, Rabbi Prof. Daniel Sperber, using his characteristic erudition, makes the case that in the twenty-first century it is time for women to be given their halakhic right, and be permitted to read from the Torah. Together with the responses of Rabbi Shlomo Riskin and Prof. Eliav Schochetman, this book is Torah study on the highest level, by scholars who thankfully choose to be engaged in an important issue affecting the Modern Orthodox world.[20]

It is with great sadness that we report the petirah of Rav Tzvi Abba Gorelick zt”l, rosh yeshiva of Yeshiva Gedolah Zichron Moshe of South Fallsburg, NY. Rav Gorelick’s most noted accomplishment was his leadership of Yeshiva Gedolah Zichron Moshe of South Fallsburg, where thousands of bochurim and yungeleit have grown in Torah and yiras Shomayim. The yeshiva was founded in 1969 in the Bronx and later relocated to South Fallsburg. Rav Gorelick was a son of Rav Yeruchom Gorelick zt”l, a talmid of the Brisker Rov zt”l who founded an elementary boys school and later a girls school, Bais Miriam, in the Bronx, and combined had an enrollment of over 800 students. The boys’ school was named Zichron Moshe after Moshe Alexander Gross z”l, a young man who was drafted into the Navy during World War II and whose ship sank during the D-Day invasion in 1944. As the neighborhood began to decline, Rav Gorelick looked for other places to move. The Laurel Park Hotel in South Fallsburg, NY, was available and Rav Gorelick decided to buy the property with money that he had from the yeshiva. In 1970, Rav Elya Ber Wachtfogel, a friend of Rav Gorelick, joined the hanhalla as rosh yeshiva. The rest is history, as the yeshiva grew and grew, becoming one of the most respected yeshivos in the world. To this day, bochurim from across the globe come to learn at Yeshiva Zichron Moshe. The yeshiva’s mosdos, under the direction of Rav Gorelick, burgeoned and currently consist of the yeshiva gedolah and mesivta, a premier kollel, as well as a cheder and Bais Yaakov elementary school. The passing of Rav Gorelick is a blow to the entire South Fallsburg Torah community and the greater Olam Hatorah. The levaya will be held tomorrow at 11 a.m. at Yeshiva Gedolah Zichron Moshe, located at 84 Laurel Park Road in South Fallsburg, NY. The aron will leave South Fallsburg at approximately 1:30 p.m. to JFK Airport, where the levaya will continue (exact time to be determined). Kevurah will take place in Eretz Yisroel.

The history of Orthodox Judaism in the United States in the years before World War II still awaits careful study. Many, in fact, are under the misconception that until the 1930’s the United States lacked great Torah scholars. The truth is that already at the turn of the twentieth century, there were many outstanding Torah scholars who had settled here. Had they remained in Europe it is likely that some of them would now be well known in the Torah world.

For a variety of reasons these rabbis were forced to leave Russia and Europe and travel to a new land. They ended up in communities throughout the country. Although it is hard to imagine it today, there were world-renowned scholars in such places as Omaha, Nebraska, Burlington, Vermont, and Hoboken, New Jersey. These were men who lived in the wrong place at the wrong time, and their communities did not appreciate the greatness that dwelled within them. The challenges of the new land were indeed difficult and unfortunately, many of these rabbis’ children did not follow the path of their fathers.

The works of these rabbis, in addition to being major contributions to Torah literature, are also priceless historical documents. They reflect a time, unlike today, when Orthodoxy was on the defensive, appearing to many to be on its way out. After their deaths, these rabbis were forgotten as were their books. Thanks to the miracles of modern technology, and the indefatigable efforts of Chaim Rosenberg, this situation is being rectified. The Torah writings of these forgotten American rabbis are now being made available. Those who peruse these works will see the learning and dedication of our American sages. They will see how these rabbis grappled with challenging halakhic problems, and how they attempted to offer religious inspiration to their congregants. It is they, the “Gedolei America,” who laid the groundwork for Orthodoxy in the United States, and for this we are all grateful.