The sukkah on Shemini Atzeret controversy

by William Gewirtz

Introduction: Arguments about eating in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret outside of Israel have a long and somewhat baffling history.[1] While not the only example of practice in opposition to the Shulchan Aruch, it appears to be among the most argued. The gemara, Rambam, the Tur and the Shulchan Aruch, written in many locales, all seem to be as unambiguous as possible in requiring one to eat in the sukkah. The Gaon, incensed by the spreading Chassidic custom to eat outside the sukkah, perhaps lemigdar miltah, went so far as to mandate sleeping in the sukkah on the night of shemini atzeret, in opposition to the Maharil, the Magen Avraham and normative custom. Despite consensus among all major decisors to require eating in the sukkah, an undercurrent of opposition has existed from at least the times of the early rishonim. Support for that opposition has been based on a number of apparently legitimate points. However, despite some early and consistent opposition, despite the logic and halakhic rationale of those who did not sit in the sukkah, and despite the problematic nature of the gemara (as explained below), I hope to explain the basis for the concluding and declarative statement in the gemara: “we sit but do not make a berakha.” In fact, the assumption, explicitly found[2] as far back as the times of the rishonim, that the declarative ruling was interpolated at a later point, is fundamental to explain both sides of the controversy. Some, as early as the times of the rishonim, argue that we can discount such geonic interpolations in deference to the original text which, as will be demonstrated, concludes not to sit in the sukkah. My goal is to explain why the interpolation is to be followed despite its ostensible opposition to the remainder of the text. The major thesis proposed is that one has to differentiate between a period of doubt as existed in both the yerushalmi and bavli when rosh chodesh was declared based on the observation of witnesses and a later period when rosh chodesh was determined using a fixed calendar. The geonic interpolation into the text of the gemara occurred at that later point; its rationale and inconsistency with the texts of the gemara needs to be addressed from that perspective. If I am correct, then in the period when rosh chodesh was declared based on the observation of witnesses, as in the times of Rav Yochanon and Rav,[3] sitting in the sukkah was not always required. However, when the fixed calendar was in use, the rabbis (eventually) decreed that sitting in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret was obligatory. It may well have been more akin to a gezairah required at their time versus a continuation of historic practice. The remainder of the paper focuses on:

- An analysis of the primary texts of the gemarot that demonstrates opposition to sitting in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret.

- A conjecture that the level of doubt in the times of the gemara was minor.

- Possible objections to sitting in the sukkah on Shimini Atzeret when not required and why they were perhaps considered overriding particularly given the level of doubt. Additionally, there are critical factors that differentiate Shemini Atzeret from other cases of yom tov sheni.

- The interpolation by the geonim, and their insistence on sitting in the sukkah despite earlier halakhic rulings.

- The objection to the gemara’s conclusion by some early authorities and their different practices.

- Reasons that would exempt you from sukkah in general, would certainly exempt you on Shemini Atzeret; mitztayer and kabbalat penai rabbo are analyzed as bases for not sitting in the sukkah.

- A summary and a modest proposal.

Section 1 – An analysis of the primary text of the gemarot demonstrates opposition to sitting in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret. The sugya in the bavli masechet sukkah beginning on 46b contains three parts:[4] A. The disagreement of Rav Yochanon and Rav. R. Judah the son of R. Samuel b. Shilath citing Rav ruled: The eighth day which may be the seventh is regarded as the seventh in respect of the sukkah and as the eighth in respect of the benediction. R. Yochanon, however, ruled: It is regarded as the eighth in respect of both. B. Two approaches to interpreting the disagreement. FIRST APPROACH: That one must dwell [in the sukkah on the eighth day] is agreed by all, they only differ on the question of the benediction. According to him who regards the day as the seventh in respect of the sukkah, we also recite the benediction [of the sukkah], while according to him who holds that it is regarded as the eighth in respect of both, we do not recite the benediction [of the sukkah]. R. Joseph observed: Hold fast to the ruling of R. Yochanan, since R. Huna b. Bizna and all the notables of his age once entered a sukkah on the eighth day which may have been the seventh, and while they sat therein, they did not recite the benediction. But is it not possible that they were of the same opinion as he who laid down that once a man has recited the benediction on the first day, he has no more need to recite it? — There was a tradition that they had just come from the fields. SECOND APPROACH: (the ikka de’amri) There are some who say that the ruling that one must not recite the benediction [of the sukkah] is agreed upon by both, and that they only differ on the question whether one must sit [inthe sukkah]. According to him who ruled that it is regarded as the seventh day in respect of the sukkah, we must indeed sit in it thereon, while according to him who ruled that it is regarded as the eighth day in respect of both, we may not even sit in it thereon. R. Joseph observed: Hold fast to the ruling of R.Yochanan. For who is the authority of the statement? R. Judah the son of R. Samuel b. Shilath [of course], and he himself sat on the eighth day which might be the seventh outside the sukkah. C. A declarative ruling that “we sit but do not make a berakha.” And the law is that we must indeed sit in the sukkah but may not recite the benediction. A. The disagreement of Rav Yochanon and Rav: Rav states that Shemini Atzeret is treated as the seventh for “this” and the eighth for “that.” Rav Yochanon states it is the considered as the eighth for “this” and “that.” The two approaches differ as to what “this” and “that” refer.[5] B. Two approaches to interpreting the disagreement: The first alternative assumes that all agree that sitting in the sukkah is obligatory; the argument concerns whether to make a berakha. In this approach Rav is asserting that one makes a berakha “leishev ba’sukkah.” The phrase “the seventh for this” refers to this obligation for a berakha on sitting in the sukkah. “The eighth for that” refers to the fact that the other prayers of Shemini Atzeret – kiddush and tefillah – mention only the eighth day and make no mention of Sukkot. Rav Yochanon asserts we make no reference to Sukkot, making no berakha when sitting in the sukkah on the eighth. It is the eight for “this” refers to sitting in the sukkah without a berakha; “the eighth for that” is interpreted identically to Rav. According to both opinions, “this” refers to whether or not a berakha is made when sitting in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret. According to both opinions, “that” refers to the mention of only Shemini Atzeret in the prayers of the eighth day. This reading is rather forced in that there does not appear to be any disagreement about what holiday ought to be referred to in the various prayers and blessings of the eighth day. While the word “this” is informative, the word “that” is not. Stating both Sukkot and Shemini Atzeret in one prayer/blessing would be contradictory; declaring a day to be both Sukkot and Shemini Atzeret was never even raised as a possibility and for good reason. The first approach then quotes practice that supports the view of Rav Yochanon, suggesting that we are to follow the opinion of Rav Yochanon. The second approach assumes not making a berakha on sitting in the sukkah is undisputed; the argument is about even sitting in the sukkah. Thus the second part of the phrase – the eighth for “that” states that common view of both Rav and Rav Yochanon omitting a berakha on sitting in the sukkah. “This” refers to the obligation to sit in the sukkah. Rav maintains for “this” it is considered the seventh and hence one is obligated to sit in the sukkah. Rav Yochanon maintains it is the eighth for “this” as well with no obligation to sit in the sukkah. Note that in this approach of the ikaa de’amri, both parts of the sentence are informative. The second approach then also quotes practice that supports the view of Rav Yochanon, suggesting that we follow the opinion of Rav Yochanon Were the sugya to end at this point, the conclusion would be clear for two reasons. Each reason itself is two-fold, resulting from both a general principle as well as a detail present in this specific case.

- First, generally, where there are two alternative approaches, the second, the ikaa de’amri, is assumed normative.[6] As well in this specific case, as indicated, the phrase of both Rav and Rav Yochanon is more informative in the formulation of the ikka de’amri.

- Second, when there is a dispute between Rav and Rav Yochanon, we generally follow Rav Yochanon.[7]As well, in this specific case the text in both alternatives immediately includes an example of practice that follows the opinion of Rav Yochanon.

Taken together, we would assume to follow the second alternative and the opinion of Rav Yochanon – and not sit in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret. According to many readings, this conclusion is made even more strongly by the yerushalmi.[8] While the bavli addresses the obligation to sit in the sukkah, the yerushalmi notes that one may not sit in the sukkah while making kiddush but one may enter the sukkah afterwards if he so desires. While some rishonim quote this yerushalmi as opposing the psak of the bavli,[9] others claim[10] that the yerushalmi is addressing a region of Israel where there was no doubt about what day the courts declared rosh chodesh. Rabbi Schacter, in support of the former opinion, observed that the yerushalmi uses the expression “leilai yom tov achron;” the plural, “leilai” is only relevant if there is a yom tov sheni on the ninth. Given this interpretation, the yerushalmi is making a rather strong point of equating the nights of the eighth and ninth, dismissing any possibility of an obligation to eat in the sukkah on the eighth.[11] C. A declarative ruling that “we sit but do not make a berakha:” Despite the reading of the gemara as outlined, the bavli concludes that “we sit but do not make a berakha.” This opinion is that of both Rav in the second alternative and Rav Yochanon in the first alternative. This ruling corresponds to two of four opinions quoted; the two alternative opinions – not sitting at all or sitting and making a berakha – are only supported by one amora and only according to one alternative. Despite that, this ruling is contradicted by the normal principles of psak where we would follow Rav Yochanon’s opinion in the second alternative, as well as the yerushalmi. The language of the gemara “shemini safek shevii,” and in particular the various amoraim cited, place the gemara not in the period of calculation based on a fixed calendar, but still during a period where rosh chodesh was declared based on observation. During that period, yom tov sheni was observed because of real doubt and also, at some point, as a precaution even during those years where doubt did not exist. Given the establishment of a fixed calendar in 359 CE by Hillel II, it is not entirely clear in exactly what era yom tov sheni was firmly established and, more importantly, when it was extended to include sitting in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret. It is entirely plausible, that this declarative ruling obligating sitting in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret followed the period debated in the gemara by multiple centuries. This resolves the apparent contradiction in the text. Why this was not stated explicitly in the gemara is only problematic if one does not assume it was obvious. Section 2 – A conjecture that the level of doubt in the times of the gemara was minor. Returning now to the period of real doubt over which day was declared rosh chodesh, the question of why was sitting in the sukkah not considered mandatory? We will deal with a number of reasons that would argue against sitting in the sukkah in the next section. However, there are two factors that would reduce the level of doubt in the times of declaration based on observation.

- First, atmospheric conditions in the Middle East around the beginning of Tishrai are normally excellent and the ability for a new moon crescent to be observed is very high.[12]

- Second, the beit din had flexibility to reduce any doubt around Rosh HaShana. When necessary, the beit din could delay declarations of rosh chodesh Elul to guarantee that a moon’s crescent would always be present to be observed on the evening following the 29th of Elul.[13]

These two factors lowered the level of doubt considerably. In addition,

- the late date in the month when Shemini Atzeret occurs and

- the effort to determine Yom Kippur

would likely reduce the level of doubt even further. After fasting only on the 10th day of Tishrai as Yom Kippur, it is entirely possible that in spite of observing yom tov sheni on the first days of sukkot, the level of doubt was minimal and insufficient to overcome the objections covered in the next section.[14] Section 3 – Possible objections to sitting in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret when not required and why they were overriding particularly given the level of doubt. Additionally, one can differentiate Shemini Atzeret from the more usual case of yom tov sheni on multiple grounds. There are two potential issues with sitting in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret, tarti de’sasreh, acting in a contradictory manner[15] and violating the prohibition to add to a mitzvah, by adding an additional day of sukkah observance, particularly on Shemini Atzeret where sitting in a sukkah is not part of the observance.[16] In the case of sitting in the sukkah, a potentially neutral act, neither is violated if some aspect of performance is compromised; however, the degree of compromise required may be in dispute. Regardless of which of the two reasons[17] is invoked, in a case of limited doubt, one or the other or both may have been sufficient to make sitting in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret either not obligatory or perhaps not even permitted without some restrictions. Both the yerushalmi and various opinions in the main text of the bavli, support this conclusion. At some point after a fixed calendar was established in the fourth century, a second day of yom tov was formalized (or maintained.)[18] As Rav Soloveitchik explained, an additional level of kedushat yom tov was applied to either an ordinary day (the day after a yom tov, isru chag) or the first day of chol hamoed because of sefaikah de’yoma. This additional level of kedusha, automatically invoked obligations for kiddush, tefillah, sippur yetziat mitzraim, etc. as well as prohibitions from work. Of course, such an approach could not be applied to Shemini Atzeret; it was already a holiday and one could not add to its kedusha, only change it. This was not done; note that we do not mention Sukkot nor do we observe the mitzvah of lulav. We simply sit in the sukkah without a berakha, something that is both different from a halakhic perspective from other observances of yom tov sheni that derive from the changed status of the day, and in Rav Soloveitchik’s opinion, less than satisfactory conceptually. He said, perhaps half-seriously, that despite his unwavering adherence to normative halakha, the position of the chassidim makes more sense. In any case, sitting in the sukkah is a unique observance with textual, historical and conceptual challenges. Section 4 – The interpolation by the geonim[19], and their insistence on sitting in the sukkah despite earlier halakhic rulings. I do not know the precise history of yom tov sheni. However, both reciting berakhot during yom tov sheni against normal halakhic practice,[20] as well as the assumed halakhic interpolation by the geonim requiring sitting in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret may both have similar origin – the need to reinforce the observance of yom tov sheni. As Dr. Haym Soloveitchik points out,[21] the case of sukkah on Shemini Atzeret proves the wisdom of insisting on a berakha; the one mitzvah of yom tov sheni for which we do not recite a berakha, resulted in widespread non-observance. It seems more than likely that this interpolation was recognized as “outside the norm” if the practice during the period of doubt did not include sitting in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret. Like berakhot, it may have been viewed as necessary particularly following a single day observance of Yom Kippur to strengthen the observance of yom tov sheni. One can only assume that the ruling’s discontinuity from the remainder of the text of the gemara was recognized and did not need elucidation; when first written, a then contemporary reader would recognize the change in practice. Section 5 – The objection to the gemara’s conclusion by some early authorities and their different practices. Given universal acceptance of the observance of yom tov sheni in the times of the rishonim, one would not have expected any deviation from the gemara’s definitive conclusion. Rabbi Schacter and Dr. Soloveitchik highlight a number of sources that illustrate the lack of universal acceptance of the gemara’s conclusion by Rashi’s rebbe and members of his family,[22] a distinguished member of the Maharil’s community,[23] and by a member of the Kolonymous family.[24] Citing the core sugya in the bavli and the yerushalmi, while certainly relevant does not in and of itself justify deviating from a clear conclusion even if it is of geonic origin. What is universally conjectured is that the cold climate of Northern Europe motivated a change. For the geonim omitting a berakha constituted enough of a heker to obviate either objection – either a tarti de’sasreh or violating a prohibition to add to a mitzvah by adding an additional day of sukkah observance. In a temperate climate, eating outside without a berakha renders sitting in the sukkah a more balanced act – clearly not a complete fulfillment of the obligation to sit in the sukkah, but, nonetheless, still honoring the institution of yom tov sheni shel galyot. However, in the cold climate of Northern Europe, even absent a berakha, either objection would, as it did in the times of real safek, make sitting in the sukkah (at least during kiddush) problematic. Note as well that the custom of returning to the sukkah during the day is consistent with this logic. During the day:

- the temperature is milder,

- there is no tarti de’sasreh from the recitation of kiddush, and

- having been absent from the sukkah at night, as Rav Soloveitchik pointed out, creates a discontinuity of performance that renders sitting in the sukkah the following day a non-violation of adding to the mitzvah.

What is perhaps most surprising is that even after the period of the Tur and Shulchan Aruch, Rav Yosef Yuzpa, the dayan in Frankfurt am Mein around the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century, when Rav Isaiah Horowitz, the Shelah HaKadosh, was Rav, in his sefer Yosef Ometz was still able to state that a family, descendant of Troyes, who does not sit in the sukkah, “has on what to rely.”[25] Section 6 – Reasons that would exempt you from sukkah in general, would certainly exempt you on shemini atzeret; mitztayer and kabbalat penai rabbo are analyzed as bases for not sitting in the sukkah. Mitztayer would exempt one from sitting in the sukkah not just on Shemini Atzeret but also on Sukkot proper. However, mitztayer is likely not binary. At one extreme, by living unnaturally in the sukkah one may not even fulfill one’s obligation, regardless of intent, as would be the case in extreme cold or very rainy weather. If, however, it is somewhat uncomfortable given the elements, sitting in the sukkah may no longer be obligatory, while it would still remain a fulfillment of one’s obligation. It seems logical as well to differentiate further the notion of mitztayer as it might apply to Sukkot versus Shemini Atzeret. Perhaps a yet lesser degree of mitztayer, not sufficient to allow eating outside the sukkah on Sukkot, might nonetheless, be more than sufficient to override and invalidate the level of heker made by not reciting a berakha. I have not seen any discussion of this notion by poskim, despite its apparent logic.[26] By analogy, one might not be legally drunk, but nonetheless it would be wise not to drive a car. Similarly, one might argue for eating outside the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret in conditions that do not meet the halakhic definition of mitztayer on Sukkot proper. Thus, cold temperatures that might not justify eating outside the sukkah on Sukkot could nonetheless justify, and indeed perhaps mandate, not eating in the sukkah on Shemini Atzeret. Rav Soloveitchik, in an attempt to justify Chassidic practice, noted the importance of the night of Shemini Atzeret, following the “guten kvitel” that Kabbalists associated with the day of Hoshana Rabbah. Like the exemption accorded to the celebration of sheva berachot even on Sukkot, when the sukkah does not comfortably provide adequate room, one can argue that the large celebrations by Chassidim where they are mekabeil penai rabbom, would similarly provide an exemption. I would add that here as well, a lesser degree of need might again be seen as voiding any heker provided by just omitting a berakha. Of course, while this explains why a tisch was held outside the sukkah, it does not in any way justify a general practice of avoiding the sukkah that has become widespread in many Chassidic circles.[27] Section 7 – A summary and a modest proposal. The discussion in the gemara covered a period of history where there was real doubt about the declaration of rosh chodesh, although in the case of Shemini Atzeret, that doubt was minimal. In the face of minimal doubt, the reasons not to sit in the sukkah prevailed. The geonim, perhaps in order to strengthen the notion of yom tov sheini, instituted the practice that “we sit but do not make a berakha.” It is not my intent to give halakhic advice; some might suggest that perhaps we ought to not even ask a local rabbi as much as follow family practice. In any case, for those who eat in the sukkah, I would consider situations of partial mitztayer that might arise, where eating in the sukkah may not be appropriate. On the other hand, given widespread laxity, one might argue that the stringencies of the geonim and the Gaon might again be particularly relevant. Of course, most fundamentally for those whose ancestors ate outside the sukkah in Warsaw, conditions are rather different in Miami,[28] or even in Baltimore or Boston.

[1] Shiurim by Rav Joseph B. Soloveitchik ztl on the Bergen Torah Beis Medrash website, as well as by Rabbi Dr. Jacob Schacter on 10/02/2007 and by Rabbi Yosef Adler on 9/29/2009, both on the YU Torah website, provide important background. I benefited greatly from their analysis; elements of their perspective are reflected. Many of the sources referenced were assembled by Rabbi Schacter (including important sources cited by Dr. Haym Soloveitchik, whose seminal review essay is quoted extensively by Rabbi Schacter) in his comprehensive

shiur on this subject. Most of the materials referenced below that are not available in standard editions of the

gemara can be downloaded in the extensive

maarei mekomot provided by Rabbi Schacter available on YU Torah in conjunction with his

shiur.

[2] One might argue this was also known during the

geonic period but assumed to be common knowledge.

[3] Certainly Rav Yochanon and Rav, the major disputants in the

bavli as well as the text of the

yerushalmi preceded the established use of a fixed calendar. We assume that the entire

sugyah, quoting only Rav Yochanon and Rav and their students, was framed in the period prior to the determination of a fixed the calendar; the conclusions of the

sugyah may have reflected practice that was followed for an even longer period.

[4] Translation below is from the Soncino Talmud.

[5] Analysis of the text of the g

emara below, benefitted extensively from “

Law and Custom in Hasidism” a translation by Shmuel Himelstein of Rabbi Dr. Aaron Wertheim’s original book, Ktav Publishing House, Hoboken, NJ. 1992, pages 279 – 286.

[6] See for example,

Hasogot haRaavad, Taanit 11. Both the Rosh and Ran on

Avodah Zarah 7a indicate that some

geonim and

rishonim always follow the second opinion. Others differentiate based on Torah, Rabbinic, monetary or religious law. For example,

tosofot, s.v.

Beshel Torah, in

Avodah Zarah 7a, quotes Rashi in a case of an

ikka de’amri as deciding according to the lenient view in cases of Rabbinic law. According to that view, given that sitting in the

sukkah on

Shemini Atzeret in times of Rav and Rav Yochanon may be a real

safek with respect to Torah law, one might follow the stricter view, the first opinion. In the times of fixed calendar, however, presumably sitting in the

sukkah on

Shemini Atzeret is only Rabbinic, and we might also follow the second, more lenient view.

[7] Rif Baba Metziah, Chapter 4, 29a, in the

dafei haRif.

[8] Sukkah Perek 4,

halakha 5, 17b.

[10] Minhagim of Rabbeinu Yitzkhak MiDura.

[11] An uncontested view of the

yerushalmi, versus contested views in the

bavli, adds additional credence to a preference for the opinion of Rav Yochanon according to the second alternative – not to sit in the

sukkah on

Shemini Atzeret.

[12] Note that the

gemara in Beitzah 4b-5a records a

singular event where witnesses were delayed in coming on the 30th of

Elul to declare that day as the 1st of

Tishrai. In early times they [the Sanhedrin] admitted the testimony about new moon throughout the [whole] day. Once, however, the witnesses were late in arriving and the Levites erred in the chant. Given how rare it is for the moon to be obscured by clouds throughout the night in the environs of Jerusalem, normally, one could expect witnesses to arrive earlier in the day. The Hebrew of the text of the

gemara – “

pa’am achat” appears to denote a rare event.

[13] Perhaps in our fixed calendar

Elul always has 29 days in commemoration of prior practice.

[14] Ritva, in complete opposition to this approach, assumed that prior to a fixed calendar, one would likely be dealing with standard case of doubt with respect to a biblical commandment and sitting in the

sukkah would clearly be mandatory.

[15] The Ran, in his commentary on the Rif, adds the element of

zilzul of

Shemini Atzeret by acting in a manner that would equate a holy day to a day of

chol hamoed.

Zilzul adds an additional dimension; the activity is not just conflicting, a

tarti de’sasre, but demeaning of

Shemini Atzeret as well. Perhaps, unlike other cases of a

tarti de’sasre, absent an element of

zilzul, a day might legitimately have a dual character. Furthermore, my nephew, Joshua Blumenkopf, noted that

tarti d’sasri is not an independent principle; it merely means that you cannot use two contradictory

kulot at the same time, something not present in this case.

[16] Were it not

Shemini Atzeret it would be no different than eating matzah on the eighth day of

Pesach because of

sefaikah de’yoma.

[17] A reason to justify sitting outside the

sukkah on

Shemini Atzeret, cited by Rabbi Werthheim, based on the

Midrash Tanchuma,

parshat Pinkhas, that one has to pray sincerely for rain, would appear to be more a rationalization than a

halakhic factor.

[18] The history and details of this complex and controversial topic are not addressed. One could assume that detailed

halakhot varied across the various possible periods of history including: the original period of uncertainty when

rosh chodesh was declared based on observation, a later period where rabbinic rulings mandated

yom tov sheni even prior to the period of the fixed calendar, the initial period of a fixed calendar and various later periods in the fixed calendar. Aligning various

sugyot to those periods could shed additional light on this topic. For example, consider the

gemara in

Beitzah 4b. Is the

gemara referring to a period when the fixed calendar was already established or is referring to an earlier period where knowledge of

sod haibur was used to reduce doubt? The latter seems to be more consistent with language that refers to knowledge of as opposed to use of the

sod haibur.

[19] The interpolation is often ascribed to Rav Yehudai Gaon.

[20] Not reciting

berakhot on a

minhag.

[21] Haym Soloveitchik, “

Olam Ke-Minhago Noheg: Review Essay,”

AJS Review 23:2 (1998): 223-234.

[23] Maharil – Minhagim,

Hilkhot lulav – 6.

[24] Yekhusai Tannaim ve Amoraim, (ed. Y. L. Maimon), pages 329-330, cited by Dr. Soloveitchik, makes (a less complete version of) the textual arguments outlined in Section 1.

[26] The Aruch HaShulchan attempts to justify various customs for only partially observance of sitting in the

sukkah as creating a yet greater

heker given cold temperatures.

[27] In addition to attribution of the trend to sit outside the

sukkah on

Shemini Atzeret to the Chassidic celebrations of the evening following

Hoshana Rabbah, see as well Rabbi Dr. Aaron Wertheim’s “

Law and Custom in Hasidism,” pages 279 – 286 for attribution to other kabbalistic sources.

[28] Miami is closer to the equator than cities in the Middle East.

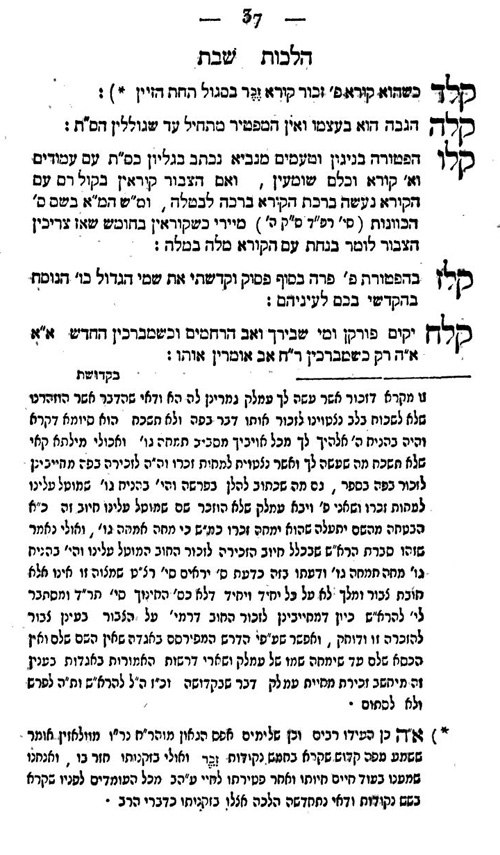

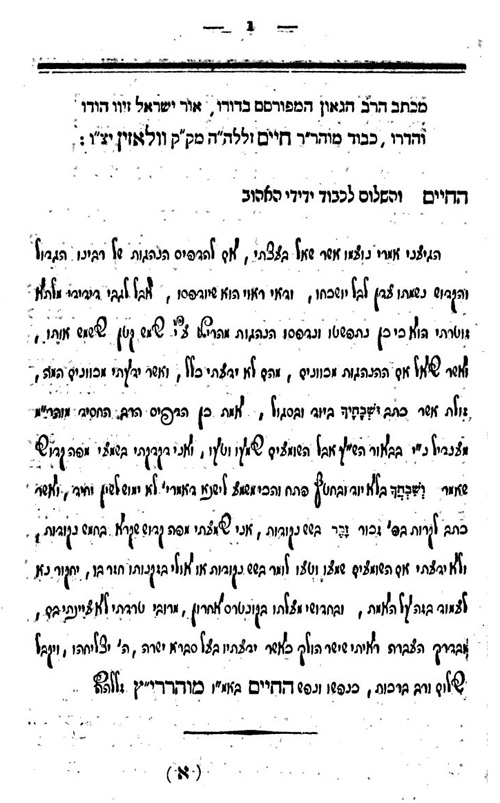

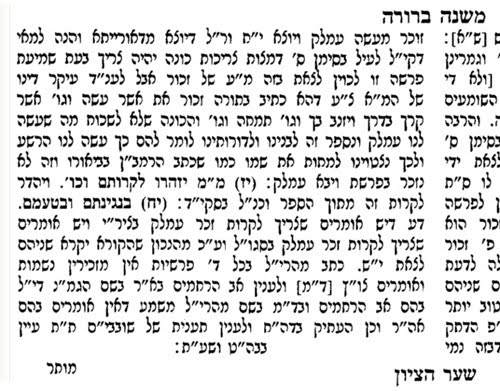

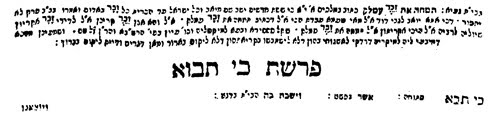

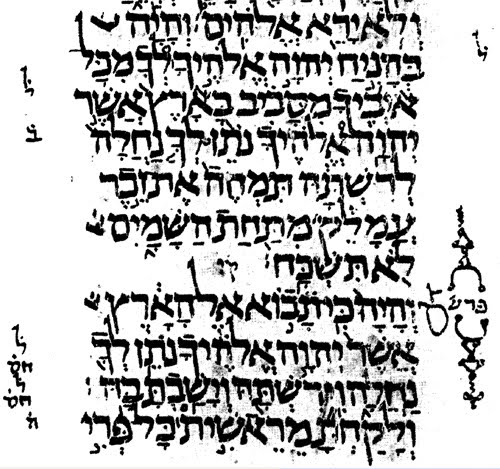

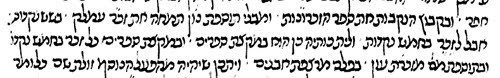

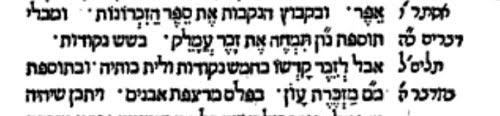

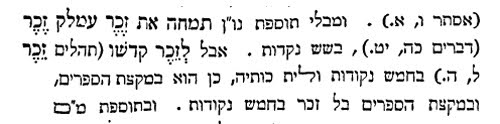

In 1832, about fifteen years after publication of Heidenheim’s edition, a book by R. Issachar Baer appeared, entitled Ma`aseh Rav, containing a description of the practices of the Vilna Gaon. The author mentions that the Gaon’s disciples disagreed over the way their teacher used to read the word zekher in Parshat Zakhor. The author attested as follows: “When he would read Parshat Zakhor, he would say zekher, with a segol under the letter zayin. R. Hayyim of Volozhin, however, whose endorsement is on the book, wrote there, `As for his writing that in Parshat Zakhor one should read [z-kh-r] with six dots, I heard from the saintly person [i.e., the Gaon of Vilna] that he read with five dots (=zeikher).’ I do not know whether those hearing him were mistaken, and thought they heard segol twice, or whether he changed his practice in his later years.”

In 1832, about fifteen years after publication of Heidenheim’s edition, a book by R. Issachar Baer appeared, entitled Ma`aseh Rav, containing a description of the practices of the Vilna Gaon. The author mentions that the Gaon’s disciples disagreed over the way their teacher used to read the word zekher in Parshat Zakhor. The author attested as follows: “When he would read Parshat Zakhor, he would say zekher, with a segol under the letter zayin. R. Hayyim of Volozhin, however, whose endorsement is on the book, wrote there, `As for his writing that in Parshat Zakhor one should read [z-kh-r] with six dots, I heard from the saintly person [i.e., the Gaon of Vilna] that he read with five dots (=zeikher).’ I do not know whether those hearing him were mistaken, and thought they heard segol twice, or whether he changed his practice in his later years.”