The Netziv, Reading Newspapers on Shabbos & Censorship (Part Two)*.

By Eliezer Brodt

Updates and clarifications

This post is devoted to discuss some of the various comments I have received from many different people regarding part one (

here). I will also add in some of the material which I had forgotten to quote for part one [some of which I was reminded of by readers] along with additional material that I have recently uncovered. I apologize for the delay in posting this. From the outset, I would like to thank all those people who sent in comments regarding the post. I hope to publish the next two parts to this article in the near future.

My email address is eliezerbrodt@gmail.com; feel free to send comments.

Firstly, on the general topic of censorship and especially related to this post, I forgot to mention Professor S. Stampfer’s remarks to me when I discussed with him the general idea of this post: “Those who impose censorship presumably assume that they are wiser than the author whose text they wish to suppress“. [See also his work Lithuanian Yeshivas of the Nineteenth Century, p. 11].[1]

In the beginning of the first part of this post [and in note two], I wrote that that this is a work in progress. In the future, I hope to write an in-depth article exploring other

Heterim for reading newspapers on Shabbos. I forgot to mention Rabbi Eitam Henkin’s article on the subject available

here. Rabbi Henkin deals with the Netziv

Heter in note 24. [Thanks to J. for reminding me about this source].

Rabbi Henkin shows the similarity of between the Pesak by R’ Moshe Feinstein to that of the Netziv’s.

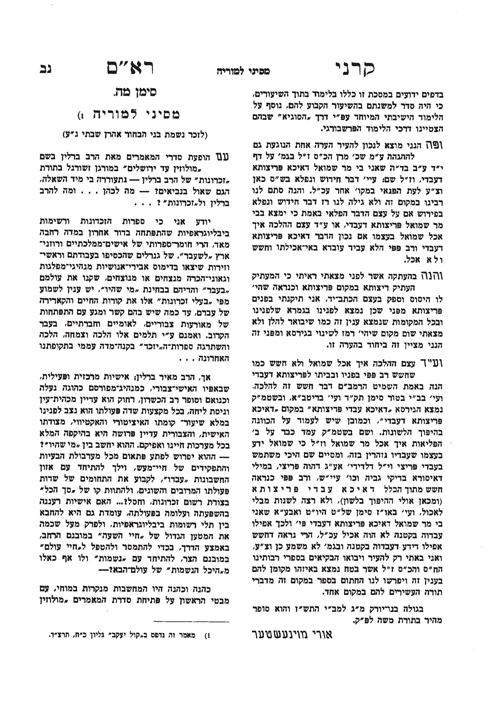

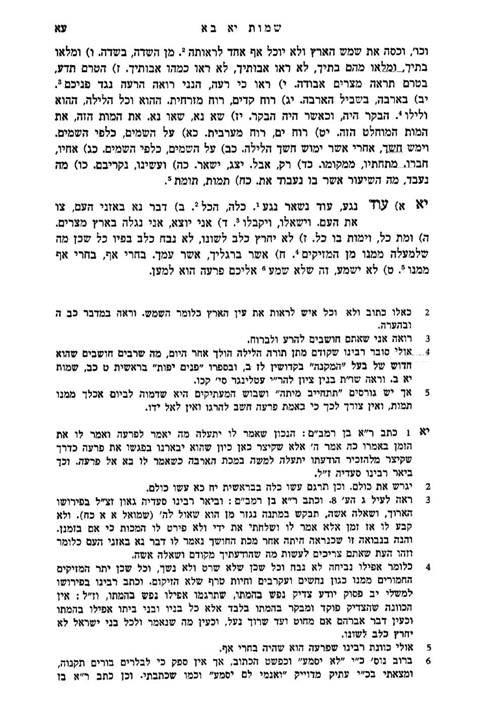

ושוב שאלתיו איך לנהוג בטילטול איגרת שלום.

תשובה: כיוון דמותר לקראות איגרת שלום בשבת, מותר לטלטלו. דהטעם שאסרו איגרת שלום בטילטול, הוא משום שמא ימחוק (רמב”ם שבת פכ”ג הי”ט, ועי’ או”ח סי’ ש”ז ט”ז ס”ק י”א), וכיוון דאנו נחשבים לגבי האי דינא כחשובים, אין לחשוש שמא ימחוק, כמו דלא חיישינן בחשובים לשמא יטה (סימן ער”ה סעיף ד’). דבאיסור קריאת איגרת נאמרו שני טעמים, אחד משום שמא ימחוק, והשני משום ודבר דבר. ואיסור ודבר דבר הוא רק באופן שקורא בפה, אבל עיון וקריאה שלא בפה מותר. ואיסור קריאה בדרך עיון בעלמא הוא רק משום שמא ימחוק, ועל טעם זה יש בו היתר דאנו נחשבים כחשובים [שו”ת אגרות משה, או”ח, ה, סי’ כב אות ד].

This Teshuvah was purportedly written to Rabbi Y.P. Bodner. However, a check in Rabbi Bodner’s work, The Halachos of Muktza, pp. 7-8, where he publishes the Teshuvot that he received from R’ Moshe Feinstein, nothing of the sort appears regarding this issue. On the other hand, it bears note that in the introduction to this Teshuvah in Igrot Moshe (#21), the editors write that R’ Moshe Feinstein had later added to them comments and corrections. [Thanks to Moshe Kaufman for this source].

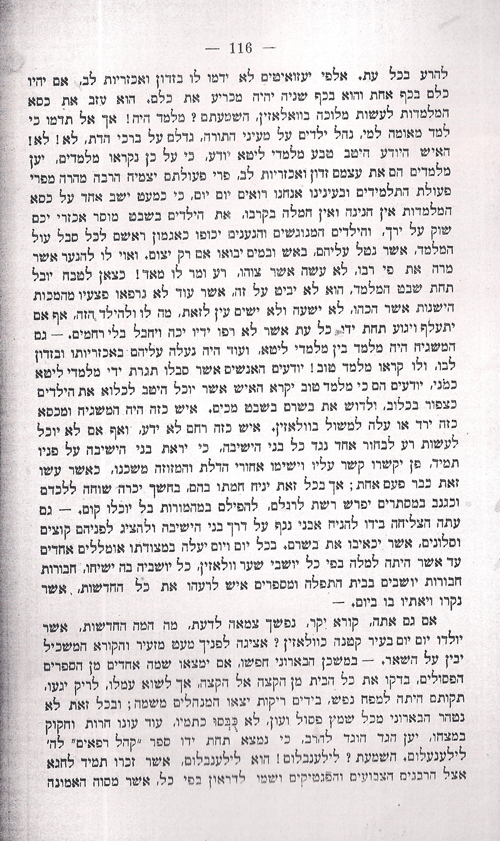

In note five I deal with relying on R’ Baruch Halevei Epstein’s Mekor Baruch. I predicted (to myself) that CFP would comment about this [as he has in the past]. Others, as well, have complained to me about relying on this work. I am not going to get into the whole subject at this time; it has been dealt with in the past by many and will probably be dealt with in the future by many more. I plan to write my own thoughts on the topic in the future, B”N. For now, I will quote something related to this [and to some of the other sources I used in this post] from Professor Stampfer’s introduction to his work Lithuanian Yeshivas of the Nineteenth Century, (p. 11) related to all this:

The sources I have used in this book… and memoirs are worthy of note. The last category is the most important, and like every other source it has both advantages and disadvantages. Memoirs sometimes provide a more detailed picture than official documents, but most were written many years after the events described and more than likely in consequence to suffer from only partial recall; they also reflect their authors attitudes at the time of writing rather than at the time of the events they describe. In most cases I have assumed that, although what was written may only be part of the truth, the authors would not have deliberately lied. Moreover, almost all my conclusions are based on several sources, so that if one source proves unreliable it does not usually affect my general conclusions.

In the case of the Netziv reading newspapers, I have provided enough ancillary evidence. As for his having permitted reading them on Shabbas and himself having done so, I believe I have provided enough sources for that as well.

CFP commented:

“I don’t know why you assume that the MB’s fabrications – to the extent that they were such – were “common knowledge”. How would the Netziv’s activities, in the privacy of his house on Shabbos, be “common knowledge”? As an insider, RBE had free reign to claim whatever he wanted. The same applies also to R’ Kook. He may not have known what his rebbe did Shabbos morning in his house. But even if he did, there’s no reason to assume that R’ Kook read the entire MB before giving a haskama on it. When assessing the validity of historical evidence, it can be useful to imagine that we’re assessing this same evidence today. Do insiders make claims about great rabbis’ practices that are of dubious veracity? Do people give haskamos on things that they’ve not read in full? It was probably no different then.”

The reason why I assume it was common knowledge is this: Volozhin itself was a small town. Almost whatever the Netziv did was noted by the hundreds of Bochurim who learnt there; other than learning there was almost nothing else to talk about. In present-day Yeshivas, one of the hot topics which Yeshivah Bochurim enjoy discussing is what their Rebbe said or did; I believe this was no different in those days. The simplest way for everyone knew that the Netziv received newspapers was that they noticed his incoming mail. As for their knowledge of what went on in his house, many bochurim ate in his house on Shabbas and Yom Tov, as is clear from the various memoir literature. Thus, I do not think that R’ Epstein had free reign to claim whatever he wanted about the goings on inside the Netziv’s home.

I agree that I cannot prove that R Kook read the whole work in its entirety; I assume it is reasonable that he read all the parts about his Rebbe. Anyone familiar with how much the Netziv meant to him should be able to understand why I believe this. Conversely, I fully agree that people give haskomos to works they do not read, however that specific point has no direct bearing on my conclusions.

One of the memoir sources I quoted a few times in part one was from the various articles written by Micha Yosef Berdyczewski. Micha came from a chassidic home, learned in Volozhin for a short time, and ended up becoming a famous non-religious writer and thinker.[2] Thus, it begs the question how one could rely on such a source.

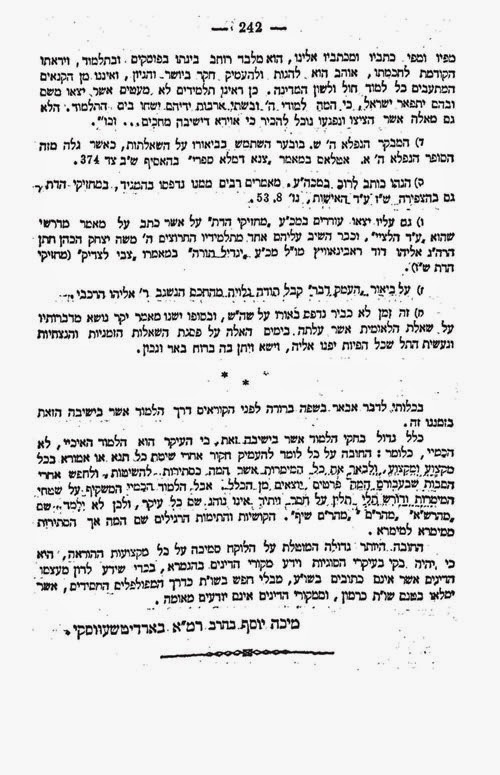

Berdyczewski wrote a lengthy article about Volozhin in Volume three of HaAssif (1886), pp. 231-242. This article was recently reprinted in his collected writings volume one (pp. 65-75) However, they did not reprint the five page appendix to the article. See the end of this post for the complete article.

The article is well written and appears to be a very accurate portrayal of Volozhin.[3] Many who wrote on Volozhin used it.

Reading the appendix we find that the Netziv helped Berdyczewski, providing him with some information for this article. Berdyczewski quotes two pieces from the Netziv (p. 239, 240).

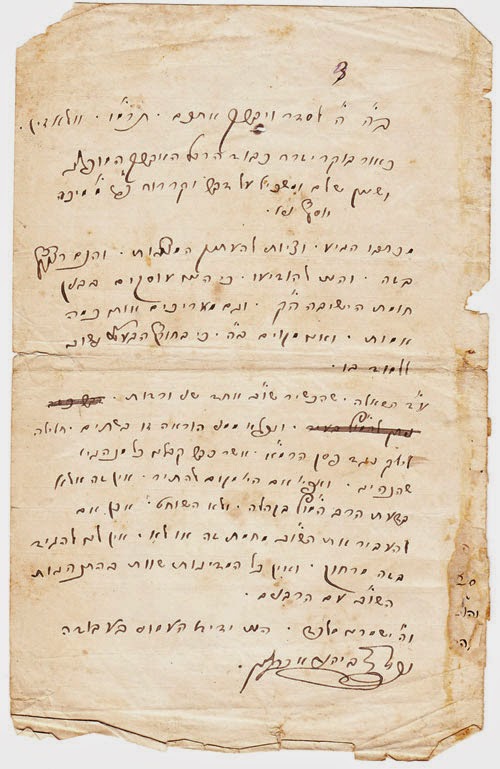

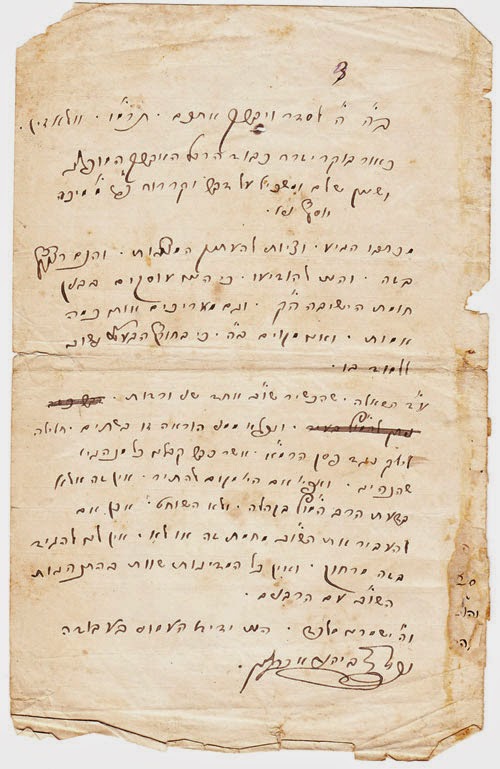

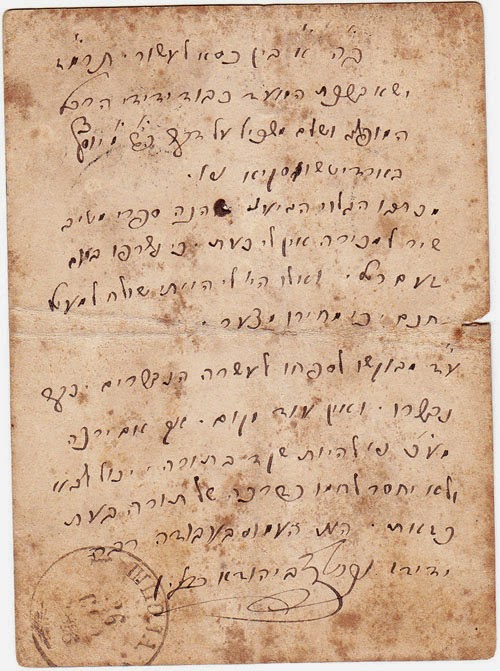

I contacted the world-renowned expert on Berdyczewski, Professor Holtzman, to inquire if this letter is still around. He was kind enough to send me a scan of the letter and another letter of the Netziv to Berdyczewski. To the best of my knowledge, these letters have never been printed.[4] Follows are the aforementioned letters, with Professor Holtzman’s kind permission, followed by my transcription.

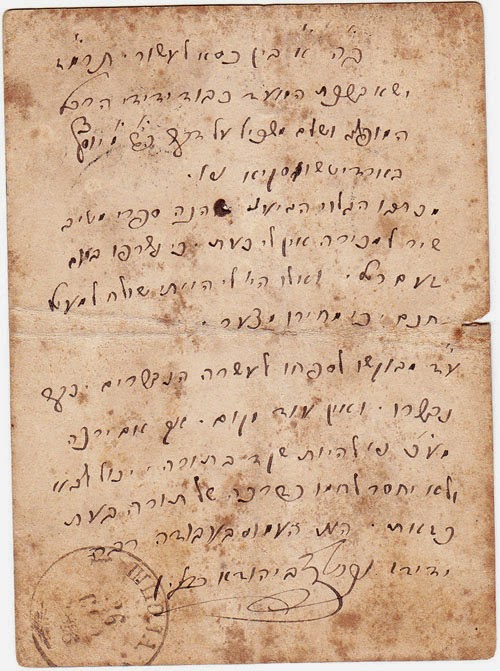

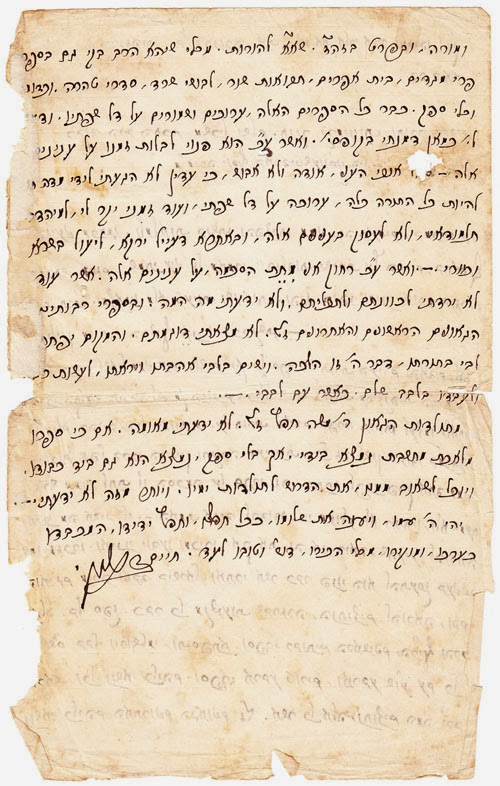

Letter 1

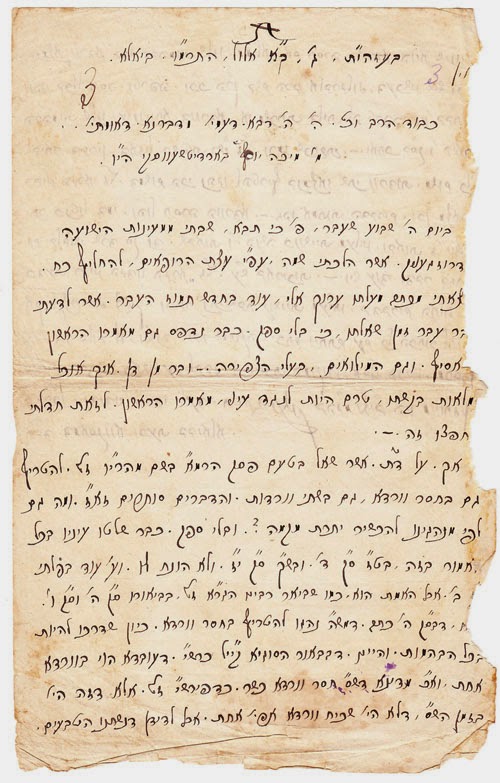

Letter 2

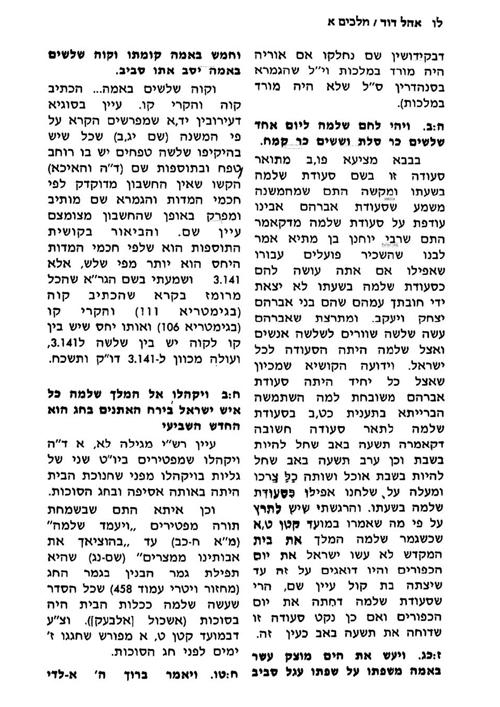

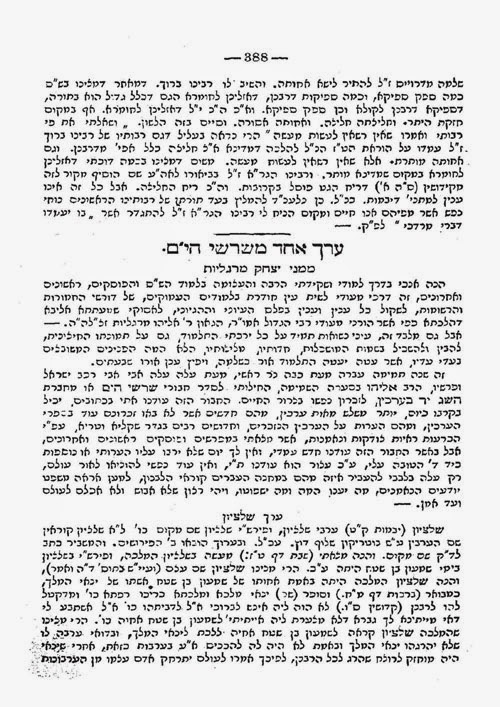

מכתב א

ב”ה ה’ לסדר ויברך אתכם. תרמ”ו. וולאזין.

כאור בוקר יזרח כבוד הר”ר האברך המופלג ושנון שלם ומשכיל על דבר יקר רוח כ”ש מ’ מיכה יוסף ני”ו.

מכתבו הגיע וציו[י]תי להעתיק המצבות. והנם רצוף בזה. והנני להודיעו. כי היינו עוסקים בבנין חומת הישיבה ה”ק. וגם מאריכים אותו כמה אמות. ואנו מקוים ב”ה, כי בחורף הבעל”ט נשוב ללמוד בו.

ע”ד השאלה שהכשיר שו”ב אחד שני ורדות.[5] ונפלא ממני הוראה זו בשתים. חלילה לילך נגד פסק הרמ”א, אשר כבר קבלנו כל מנהגיו שהנהיג. ואפי’ אם הי’ מקום להתיר, אין זה אלא בדעת הרב המו”ץ בקהלה, ולא השוחט. אכן אם להעביר את השו”ב מחמת זה או לא, אין לנו להגיד בזה מרחוק. ואין כל המדינות שוות בהתנהגות השו”ב עם הרבנים.

וה’ ישמרנו מלכד. הנני ידידו העמוס בעבודה

מכתב ב

ב”ה א’ בין כסא לעשור תרמ”ז

ישא ברכת המועד כבוד ידידי החכם המופלג ושלם משכיל על דבר כ”ש מ’ יוסף בארדיטשווסקיא ני”ו

מכתבו הגלוי הגיעני [ו]הנה ספרי מטיב שיר[6] למכירה אין לי כעת כי נשרפו ביום זעם ר”ל. ואלו הי’ לי הייתי שולחו למעל[ת]ו חנם כי מחירו מצער.

ע”ד מבוקשו לספחו לעשרה הנבררים[7] כבר נבררו. ואין עוד מקום. אך אם ירצה מע”כ נ”י להיות שקד בתורה, יכול לבא ולא יחסר לחמו כדרכה של תורה בעת הזאת.

הנני העמוס בעבודה רבה

ידידו נפתלי צביהודא ברלין

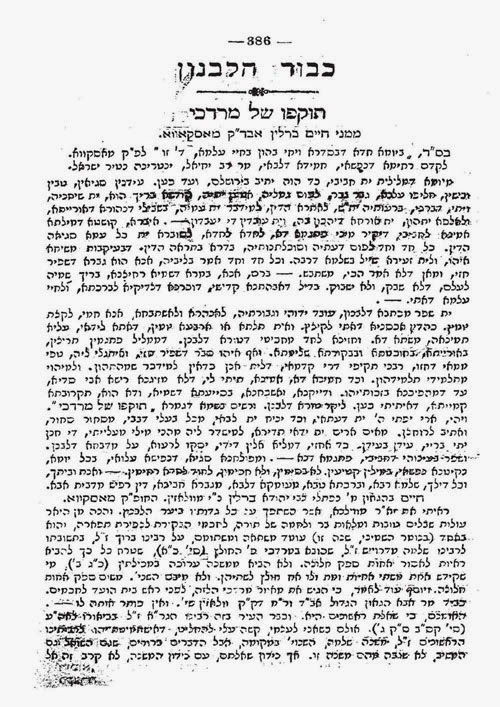

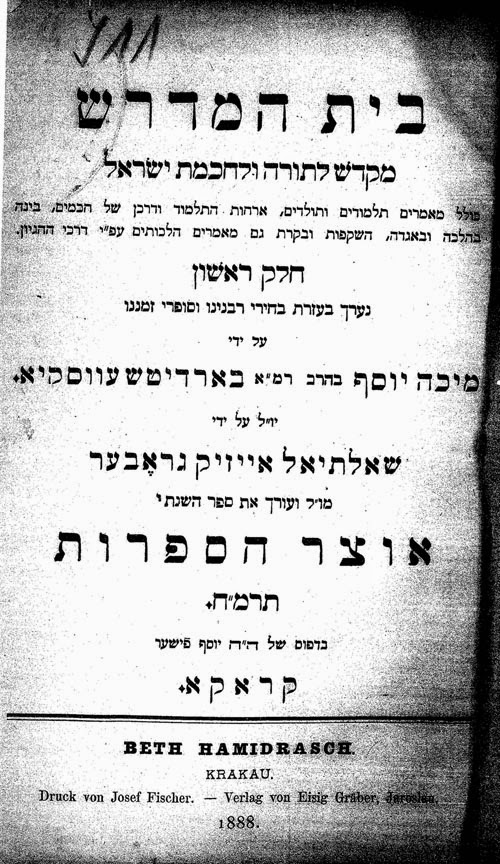

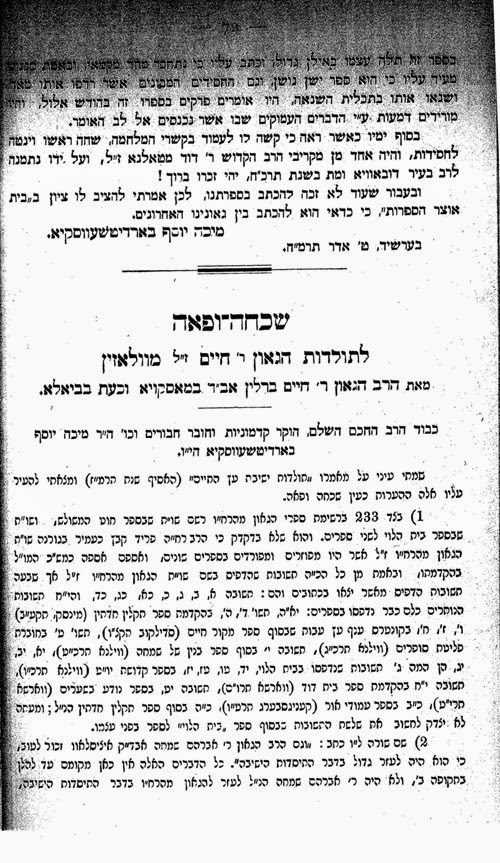

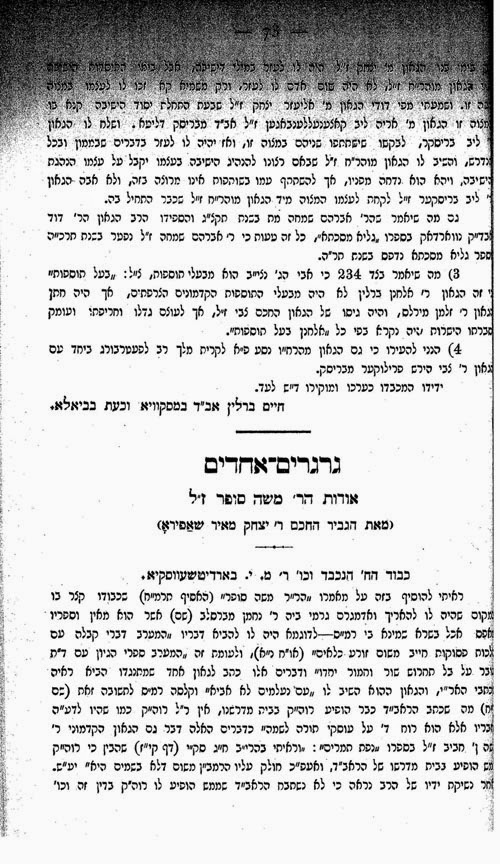

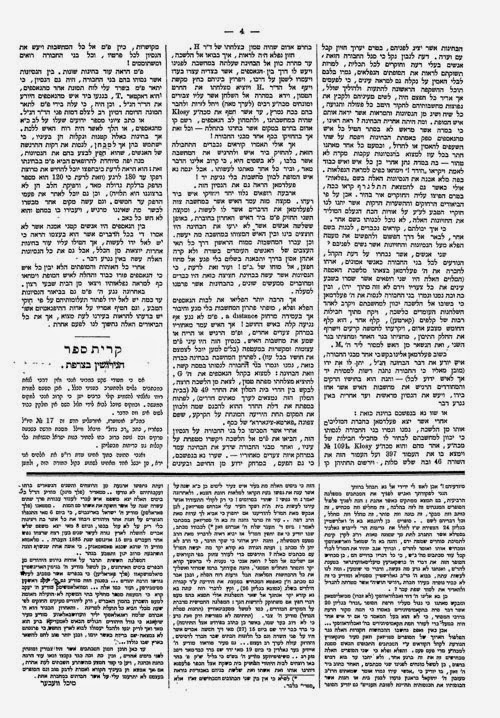

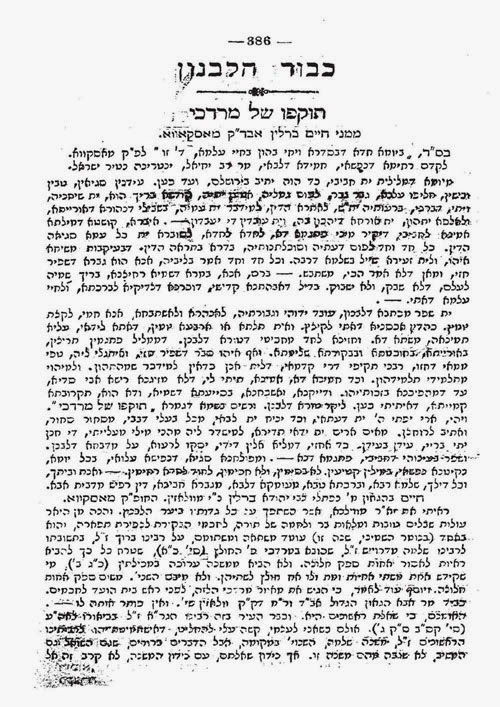

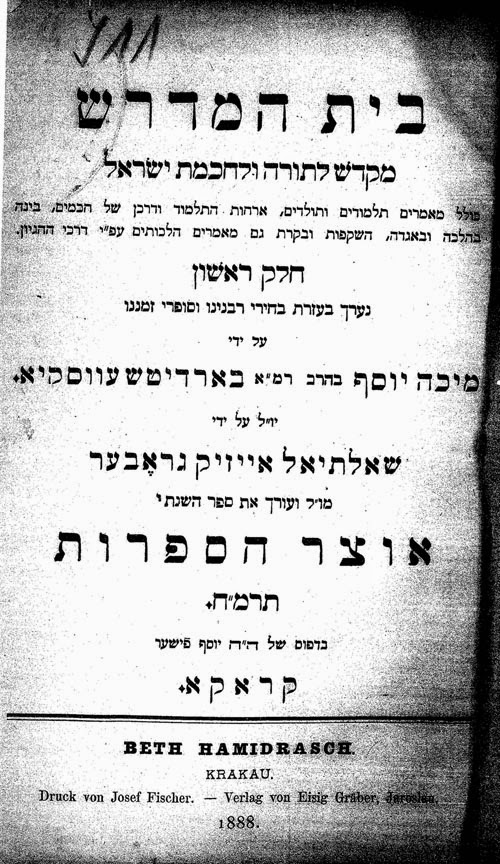

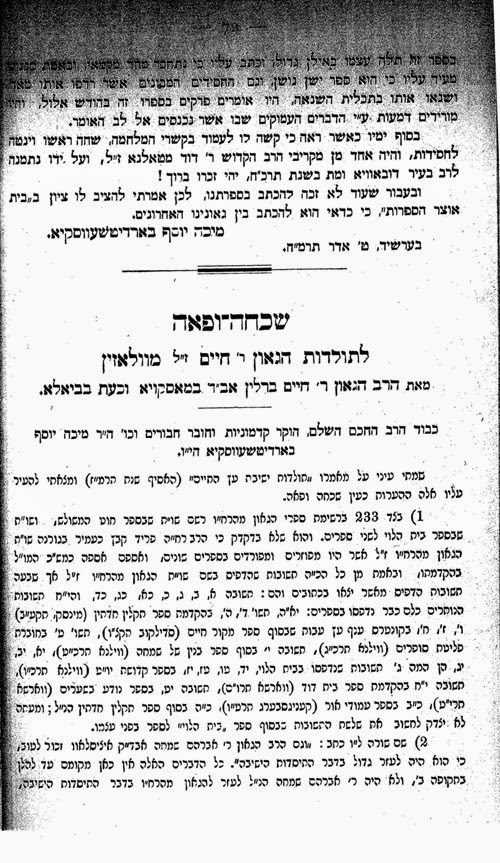

In 1888 Berdyczewski printed a journal called Beis Hamedrash which included an article from Rabbi Chaim Berlin [!] where Reb Chaim corrects and adds some important information to Berdyczewski famous article about the History of Yeshivat Volozhin. In this article, which it is obvious Reb Chaim Berlin read, Berdyczewski mentions the Netziv’s reading newspapers and a listing of the many newspapers the Bochurim of Volozhin read in his time.

Rabbi Chaim Berlin’s article was recently reprinted in the

Nishmat Hayyim, Mamorim u’Mechtavim, (pp. 329-331) but the name of the person this letter was addressed to, Micha Yosef Berdyczewski, was edited out. [It appears that the commenters on this

forum were not aware of this]. See the end of the post for the original article of Rabbi Chaim Berlin.

Professor Holtzman sent me the original letter of Rabbi Chaim Berlin to Berdyczewski and an additional letter of Rabbi Chaim Berlin to him. These letters were not printed before to the best of my knowledge.

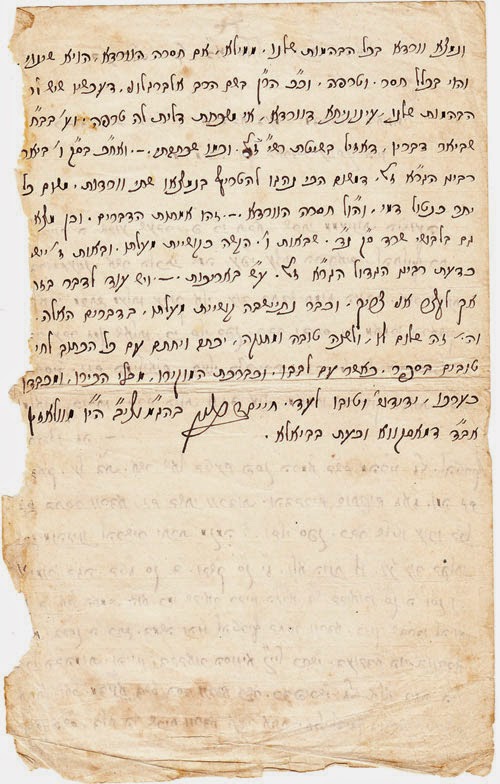

Letter 1

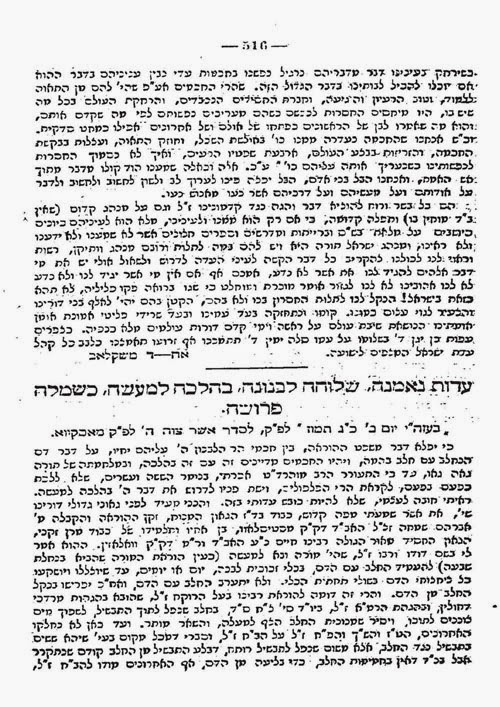

מכתב א

בעזהי”ת. ג’, ך”א אלול, התרמ”ו. ביאלא.

כבוד הרב וכו’ ה’ ה’ רבא דעמי’ מדברנא דאומתי’

מ’ מיכה יוסף בארדיטשעווסקי הי”ו

ביום ה’ שבוע שעבר, פ’ כי תבא, שבתי ממעינות הישועה דרוזגעניק. אשר הלכתי שמה, עפ”י עצת הרופאים, להחליף כח [מ]צאתי מכתב מעלתו ערוך אלי, עוד בחדש תמוז העבר. אשר לדעתי [כ]בר עבר זמן שאלתו, כי בלי ספק כבר נדפס גם מאמרו הראשון [בה]אסיף. וגם המילואים, בעלי הצפירה. – ובר מן דן, אין אוכל [ל]מלאות בקשתו, טרם היות לנגד עיני, מאמרו הראשון. לזאת חדלתי [מ]חפצו זה.

אך. על ד”ת. אשר שאל בטעם פסק הרמ”א בשם מהרי”ו ז”ל. להטריף גם בחסר וורדא, גם בשתי וורדות. והדברים סותרים זא”ז. ומה גם לפי מנהגינו להכשיר יתרת מקמה?. ובלי ספק. כבר שלטו עיניו בכל [ה]אמור בזה, בט”ז ס”ק ד’. ובש”ך ס”ק י”ז. ולא הונח לו. וע’ עוד בפלתי [ס”ק] ב’. אבל האמת הוא, כמו שביאר רבינו הגר”א ז”ל, בביאורו ס”ק ה’ וס”ק ו’. [?] דבס”ק ה’ כתב. דמש”ה נהגו להטריף בחסר וורדא. כיון שדרכו להיות בכל הבהמות. והיינו. דבבאור הסוגיא קיי”ל כרש”י. דעובדא הוי בוורדא אחת. וא”כ מדינא דש”ס חסר וורדא כשר. כדפירש”י ז”ל. אלא דזה הי’ בזמן הש”ס, דלא הי’ שכיח וורדא אפי’ אחת. אבל לדידן דנשתנו הטבעים. ונמצא וורדא בכל הבהמות שלנו, ממילא, אם חסרה הוורדא, הויא שינוי והוי בכלל חסר. וטרפה. וכ”כ הר”ן בשם הרב אלברגלוני, דעכשיו שיש [לכל] הבהמות שלנו, עינוניתא דוורדא, אי משכחת דלית לה טרפה. וע’ בב”ח שביאר דבריו, דאזיל בשיטת רש”י ז”ל. וכמו שכתבתי.-. ואח”כ בס”ק ו’ ביאר רבינו הגר”א ז”ל, דמשום הכי נהגו להטריף בנמצאו שתי וורדות. משום כל יתר כנטול דמי, והו”ל חסרה הוורדא.-. זהו אמתות הדברים. וכן מצא[תי] גם בלבושי שרד ס”ק נ”ד. שבאות ו’. הקשה כקושיית מעלתו. ובאות ז’ יישב כדעת רבינו הגדול הגר”א ז”ל. ע”ש באריכות.-. ויש עוד לדבר בזה אך לעצר אני צריך. וכבר נתיישבה קושיית מעלתו, בדברים האלה. והי’ זה שלום לו, ולשנה טובה ומתוקה, יכתב ויחתם עם כל הכתוב לחי[ים] טובים בספר. כאשר עם לבבו. וכברכת המוקירו, מבלי הכירו, ומכבדו כערכו, ידידו”ש וטובו לעד. חיים ברלין בהג”מ נצי”ב הי”ו מוולאזין אב”ד דמאסקווא וכעת בביאלא.

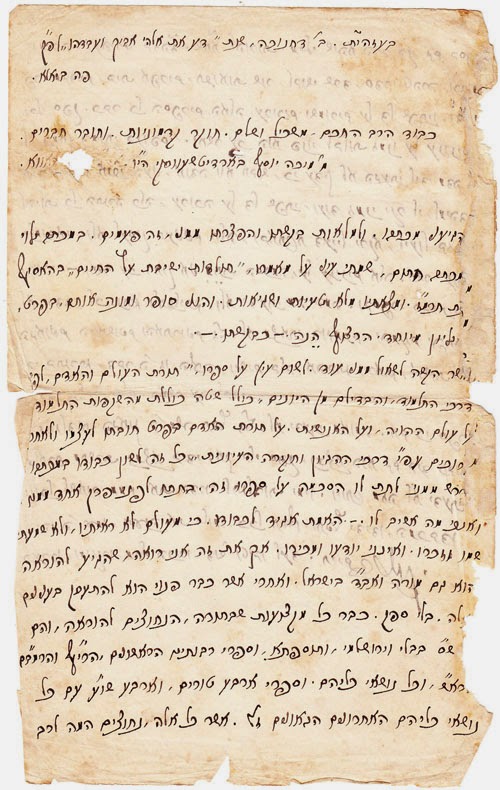

מכתב ב

בעזהי”ת. ב’ דחנוכה, שנת “דע את אלהי אביך ועבדהו” לפ”ק

פה ביאלא.

כבוד הרב החכם, משכיל ושלם. חוקר קדמוניות. וחובר חברים.

מ’ מיכה יוסף באדיטשעווסקי הי”ו [??]

הגיעני מכתבו. ולמלאות בקשתו והפצרתו ממני, זה פעמים. במכתב גלוי [וב]מכתב חתום, שמתי עיני על מאמרו, “תולדות ישיבת עץ החיים” בהאסיף [שנ]ת תרמ”ז. ומצאתיו מלא טעויות ושגיאות. והנני סופר ומונה אותם, בפרט, [ב]גליון מיוחד, הרצוף הֵנה – כבקשתו.-.

ואשר הקשה לשאול ממני עוד. לשום עין על ספרו, “תורת העולם והאדם, לפי דרכי התלמוד, והבדילם מן היונים, כולל שטה כוללת מהשקפות התלמוד על עולם ההויה, ועל האנושות. על תורת האדם בפרט חובתו לעצמו ולאחר [ע]רוכים עפ”י דרכי ההגיון וחקירה העיונית”, כל זה לשון כבודו במכתבו [ש]דרש ממני לתת לו הסכמה על ספרו זה. בתתו לפני מפרק אחד ממנו. ואנכי מה אשיב לו. – האמת אגיד לכבודו. כי מעולם לא ראיתיו, ולא שמתי שמו וזכרו. ואינני יודעו ומכירו. אך את זה אני רואה שהגיע להוראה [ו]הוא גם מורה ואב”ד בישראל. ואחרי אשר כבר פנוי הוא להתעסק בענינים [א]לה. בלי ספק. כבר כל מקצועות שבתורה, הנחוצים להוראה, והם ש”ס בבלי וירושלמי, ותוספתא, וספרי רבותינו הראשונים, הרי”ף והרמב”ם [וה]רא”ש, וכל נושאי כליהם. וספרי ארבע טורים, וארבע שו”ע עם כל נושאי כליהם האחרונים הגאונים ז”ל. אשר כל אלה, נחוצים המה לרב ומורה, ובפרט בזה”ז. שא”א להורות. מבלי שיהא הרב בקי גם בספר פרי מגדים, בית אפרים, תבואות שור, לבושי שרד, סדרי טהרה, וכדו[מה.] ובלי ספק. כבר כל הספרים האלה, ערוכים ושמורים על דל שפתיו וד[מי] לי’ כמאן דמנחי בקופסי’. ואשר ע”כ הוא פנוי לבלות זמנו על ענינים אלה – [אבל] אנכי העני, אודה ולא אבוש, כי עדין לא הגעתי לידי מדה זו להיות כל התורה כלה, ערוכה על דל שפתי, ועוד זמני יקר לי, למיהדר תלמודא, ולא לעסוק בענינים אלה, ובאתרא דעייל ירקא, ליעול בשרא וכוורי.-. ואשר ע”כ רחוק אני מִתֵת הסכמה, על ענינים אלה. אשר עוד לא ירדתי לכוונתם ולתכליתם. ולא ידעתי מה המה. ובספרי רבותינו הגאונים הראשונים והאחרונים ז”ל. לא מצאתי דוגמתם. והמקום יפתח לבי בתורתו, דבר ה’ זו הלכה. וישים בלבי אהבתו ויראתו, לעשות [רצונו] ולעבדו בלבב שלם. כאשר עם לבבי.-.

מתולדות הגאון ר’ משה חפץ ז”ל. לא ידעתי מאומה. אם כי ספרו מלאכת מחשבת נמצא בידי. אך בלי ספק. נמצא הוא גם ביד כבודו. ויוכל לשאוב ממנו, את הדרוש לתולדות ימיו. ויותר מזה לא ידעתי.-.

יהי ה’ עמו, ויענה את שלומו, ככל חפצו, וחפץ ידידו, המכבדו כערכו, ומוקירו, מבלי הכירו, דו”ש וטובו לעד. חיים ברלין

A short time later Berdyczewski published several more articles related to Volozhin, one of which was a five chapter piece about the Yeshivah, titled Olam Ha-Atzeilus, printed in Hakerem in 1888. While this article does contain valuable information, it’s written in a different style than his earlier article. It was reprinted in the excellent collection Yeshivot Lita (pp. 132-151) and in the small Booklet Pirkei Volozhin (1984).

Another series of articles about Volozhin, written at the same time, was called Tzror Mechtavim Me-Eis Bar Be Rav and caused a great commotion. The series was printed in Ha-Melitz, starting from January 1888 and onwards. The series was written under a pen name, and only in the last issue did Berdyczewski sign his name.

In a memoir from someone who learnt in Volozhin at the time Berdyczewski’s articles were printed we find:

בעת ההיא הופיע בהמליץ פיליטון שנתן לדפוס ע”י בערדיצעוסקי… במאמר ההוא ציר הסופר בציורים נאמנים את חייהם של בני הישיבה את ענים ומרודם ואת לחציהם ובשבט עברתו הכה על ימין ועל שמאל את מנהלי הישיבה את חקיהם ומשפטיהם וכמעביר צאנו תחת שבטו כן העביר תחת שבט הבקורת את כל המנהגים מן ראש הישיבה עד השמש. המאמר ההוא עשה רושם גדול על מנהלי הישיבה וביחוד על ראשי הישיבה. בני הישיבה התיחסו אל המאמר ההוא בכובד ראש והעריצו את הסופר… [יהושע ליב ראדוס, זכרונות, עמ’ 68].

Radus continues in his autobiography that they had suspected someone specific in the Yeshiva for having authored these articles and that although Berdyczewski was involved in their writing, he was not the author. Radus writes that while this person was thrown out of Volozhin, he eventually became a renowned Rav. Unfortunately he does not name the person.

Regarding the Mekor Baruch, I wrote: “His work received a glowing haskamah from Rav Kook”.

In volume four of Mekor Baruch, at the end of the volume (pp. 14-15) R’ Epstein prints a letter from Rav Kook about the sefer but he does not print the whole letter. Rav Kook writes:

אבל יחד עם סדרי הזכרונות… וחותם האמת הטבוע עליהן…

For recent discussion about this letter see Eitam Henkin and Shmaria Gershuni, Alonei Mamreih 122 (2009) (p.186).

Another comment regarding Mekor Baruch’s report was sent to me from Moshe Maimon:

R. Mazuz in his Mekor Ne’eman references the Mekor Baruch’s report twice. On p. 95 he relies on it to be Matir reading newspapers on shabbos and on p. 254 in a letter to Moshe Chavusha he quotes it to defend himself for citing R. Ovadia’s practice of listening to the radio every day.

More on the Netziv and reading newspapers:

In 1881, Rabbi Baruch Epstein wrote an article in Hamelitz about Volozhin defending it from various attacks in the newspapers. He describes Volozhin and the Netziv in depth:

מה אומר ומה אדבר על תכונת נפש נעלה של האיש הדגול מרבבה הגאון הנאור ר’ נצי”ב הי”ו… רוב מכ”ע לב”י ואחד בשפת רוססיא נמצאים בביתו, והוא אחד מן הזריזים הקודמים לקנות ספר חדש היוצא בעברית, יהיה מאיזה רוח ושיטה שהוא…”. [המליץ, יז, יום ב אדר תרמ”א (1881), גליון 3, עמ’ 54].

I am doubtful he would write something like this in a public forum, during the Netziv’s lifetime, if it was not true.

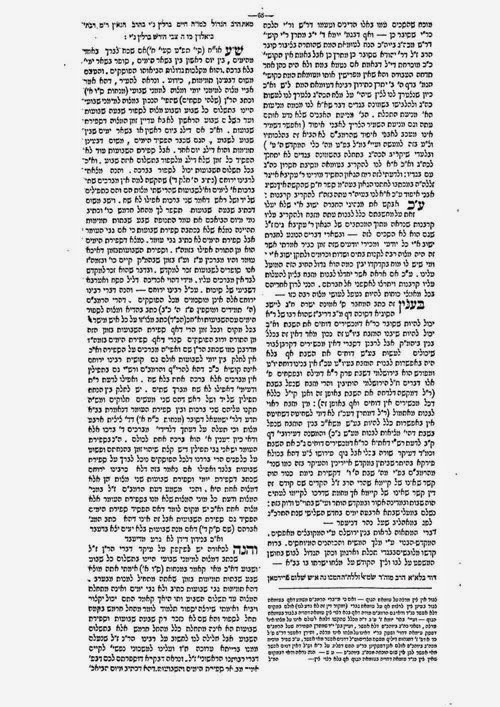

More on the Netziv and reading newspapers

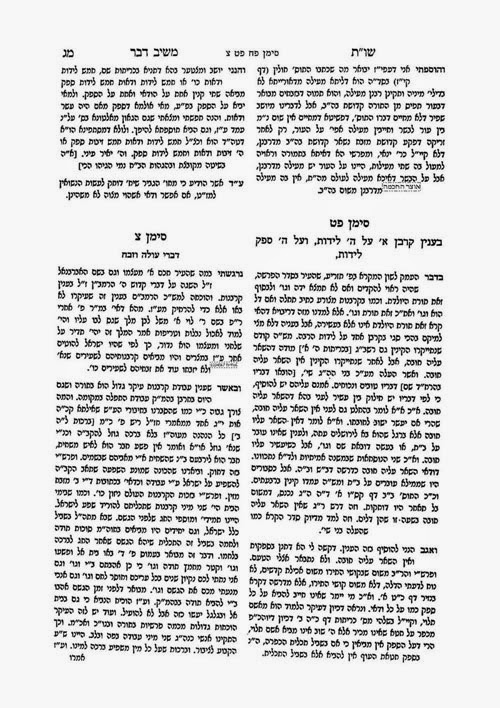

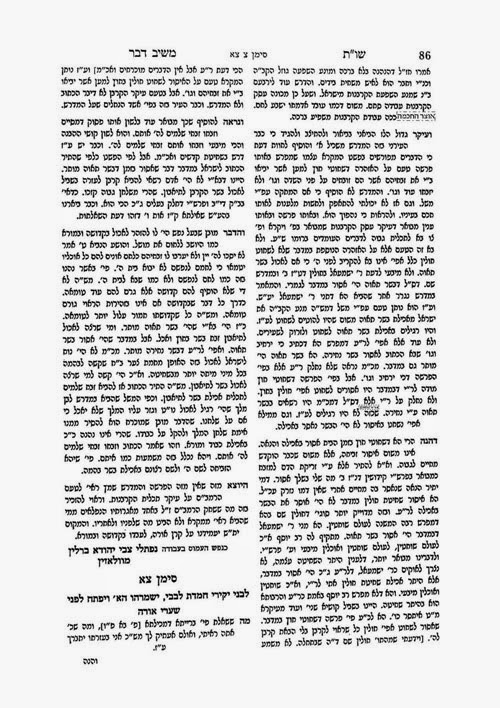

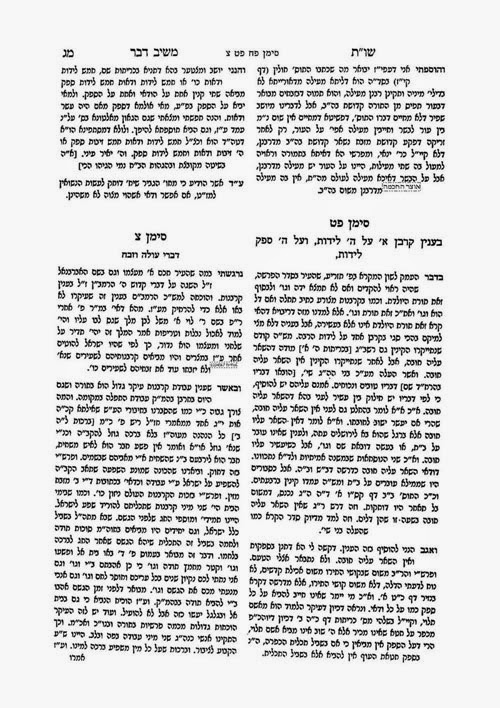

In Shut Meishiv Davar we find a few more times that the Netziv refers to articles he read in newspapers.

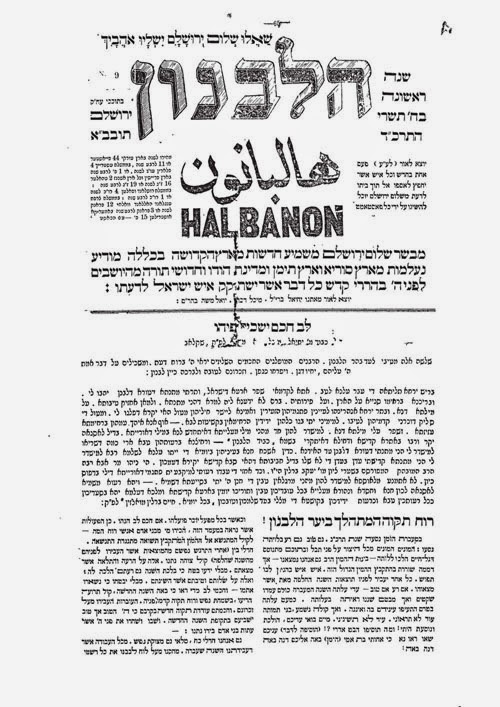

ראיתי בכבוד הלבנון (משיב דבר, ב, סי’ קח)

ע”ד מאמר הגירושין בצרפת, הגיע לפה עלה הצפירה נו’ 44 וראיתי מאמר ותרגז בטני… (משיב דבר,ג, סי’ מט).

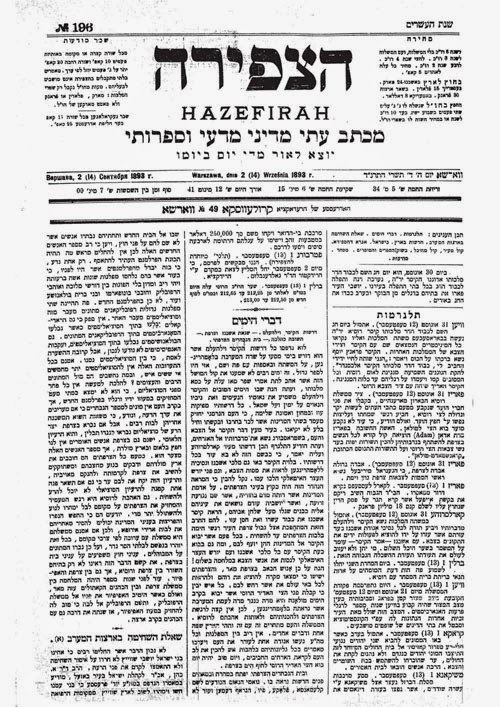

This last Teshuvah was actually printed in the

Ha-Tzefirah before it was printed in the

Meishiv Davar. Here is the original article:

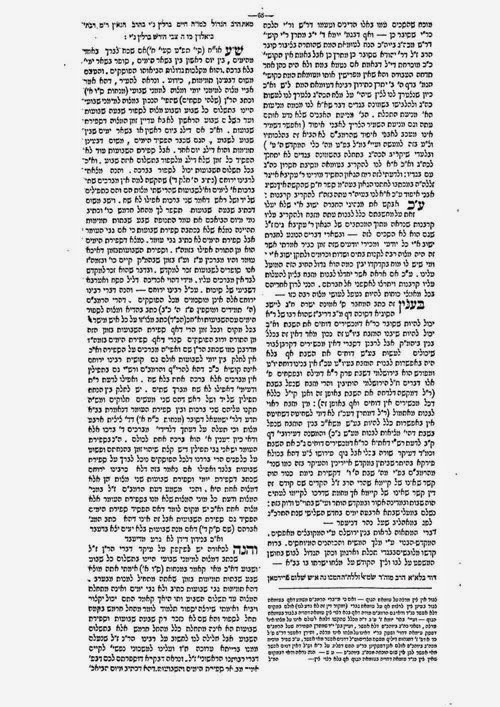

But elsewhere in Meishiv Davar we find the Netziv writes:

ראיתי שהמופלג ומדקדק הר’ אברהם לאנדמאן שי’ דקדק אחרי מש”כ בהעמק דבר… [משיב דבר, ב, סי’ קט].

In Igrot HaNetziv Me-Volozhin (p. 60) this teshuvah was printed with a few more words:

ראיתי בהמליץ נו’ 120 אשר המפולג ומדקדק הר’ אברהם לאנדמאן שי’ דקדק אחרי מש”כ בהעמק דבר…

Even more interesting is this letter was originally printed in the Hameilits. Here is the original:

Rabbi Chanoch Taubes writes about R’ Epstein’s claims of the Netziv Reading newspapers:

‘המגיד’ בטאונם של חוגי ההשכלה. בהעדר חלופה מתאימה היה נכנס גם לבתים כשרים. אם נכונה היא עדותו של ר’ ברוך עפשטיין בזכרונותיו עמ’ 1974 הרי שהמגיד היה דרכו להתקבל בביתו של הנצי”ב מוולוז’ין זצ”ל בכל ערב שבת לפנות ערב, ובלילה לא קרא אותו [הנצי”ב], מפני שליל שבת היה קדוש לו לחזור בעל פה על המשניות ממסכתות שבת… כותב הטורים כשלעצמו, חושד שמפאת נטיותיו המשכיליות של ר’ ברוך עפשטיין ביקש להכשיר את השרץ בעובדות שאינן מדויקות… חיזק להשערה זו תמצא בעמוד שאחריו ביחסו הלעגניי והעוקצני לשבועון המתחרה הלבנון. גם את חיצי הלעג ירה על בסיס עובדות לא מדויקות, בלשון המעטה. הלבנון עיתון כשר היה אשר ביוזמתו של רבי ישראל סלנטר, מחולל תנועת המוסר, קיבל על עצמו רבי מאיר להמן זצ”ל אב”ד מיינץ את מלאכת עריכתו… [סופה וסערה, א, בני ברק תשע”ה, עמ’ 77-78 [=סופה וסערה, א, בני ברק תשס”ח, עמ’ 63-64].

However, it is apparent that based upon further evidence, Rabbi Taubies claim has no basis.

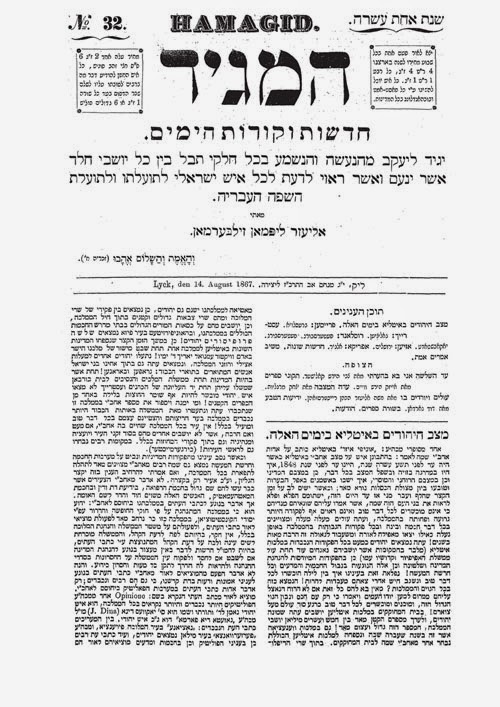

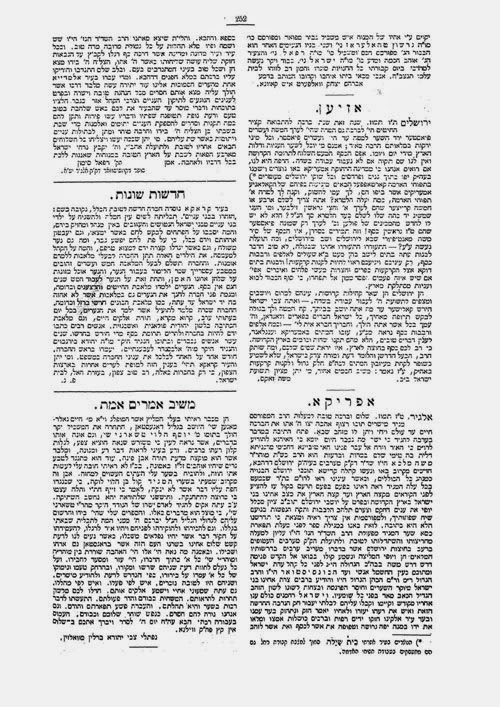

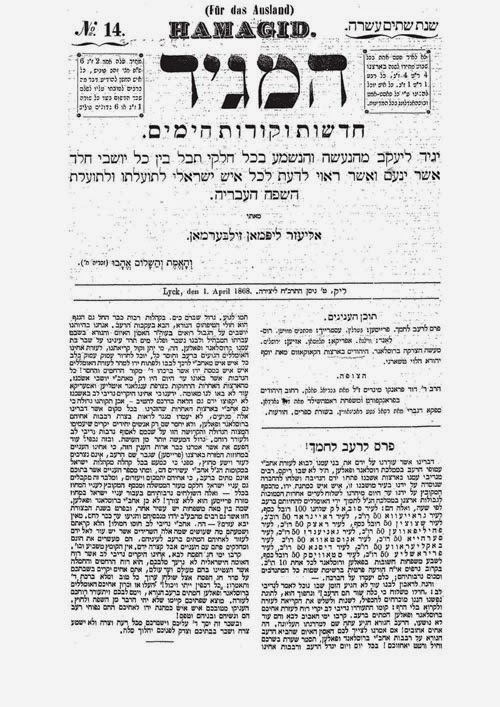

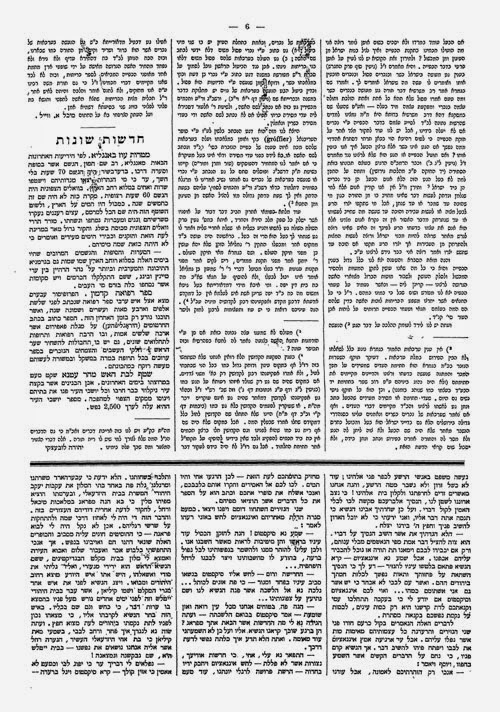

In part one of this article I cited a remarkable story from R’ Eliyahu Milikovsky about a Response that the Netziv wrote to an article in the HaMaggid. One might say that R’ Milikovsky’s memory failed him and he recalled the wrong newspaper. However here is the newspaper article written by the Netziv in the HaMaggid, referred to in this story. [Quoted in Igrot HaNetziv Me-Volozhin, pp. 54-56]

The Netziv was responding to this article.

That aside, as we have shown in part one of this article, the Netziv quotes HaMaggid in his seforim. These quotes and their subsequent censorings were discussed there as well.

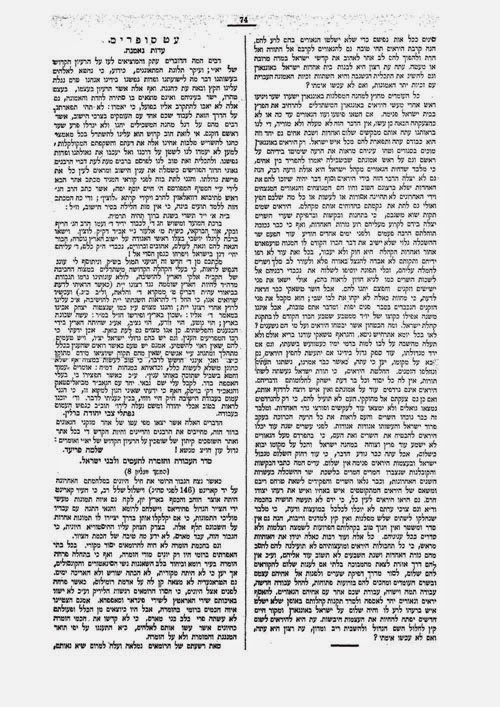

Here are some additional articles by the Netziv published in HaMaggid

This is reprinted in Igrot HaNetziv Me-Volozhin, (pp.198-199)

There are more pieces of the Netziv in HaMaggid which will be discussed in a later post.

It bears mention that many other Gedolim also read and wrote in HaMaggid; see for example this piece of the

Dikdukei Sofrim (one of many).

R’ Chaim Berlin (more on this shortly) also read the HaMaggid.

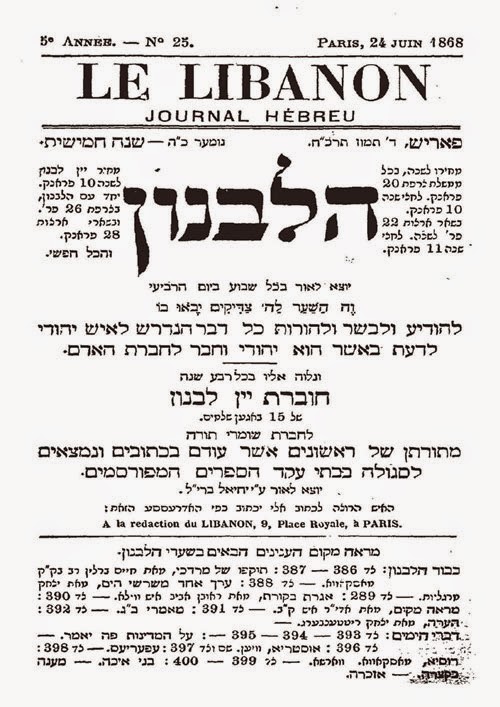

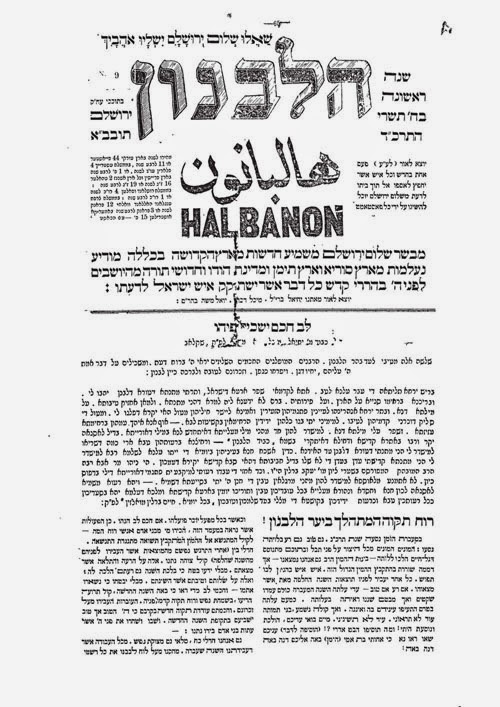

New evidence about the Netziv reading newspapers on Shabbas (and Censorship):

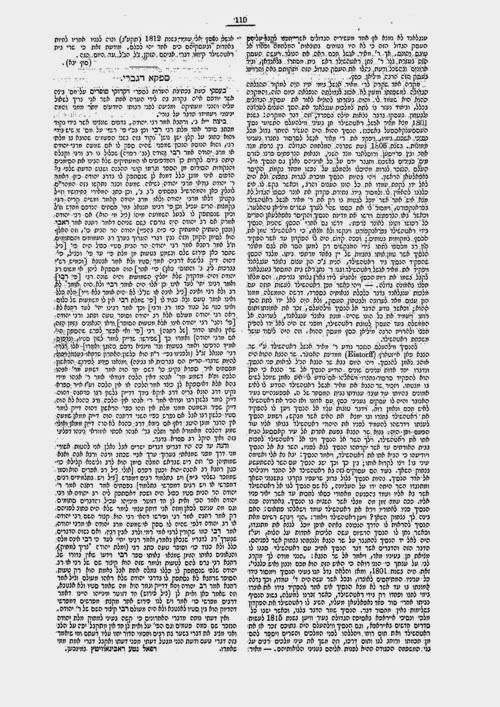

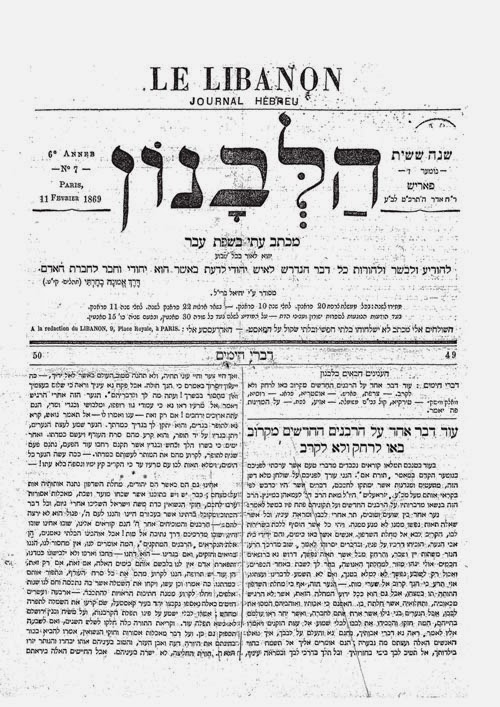

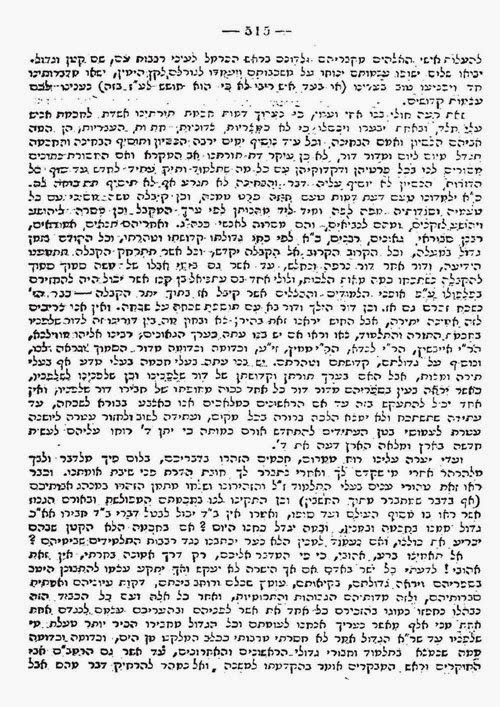

At the end of the January 7, 1869 issue of the Ha-Levonon newspaper there appeared an announcement regarding a new sefer that was to be printed soon for the first time from manuscript, namely The Ritva’s work on Nidah and his Sefer Ha-Zechron. Sefer Ha-Zechron is a defense of the Rambam from the Ramban’s various critiques in his Pirish Al Hatorah. After the announcement, Zalman Stern wrote a comment dealing with the subject of the Rambam’s reasoning for Korbonos.[8]

Less than a month later, in the February 11th issue of the Ha-Levonon newspaper, the Netziv wrote a lengthy response to Stern’s comment. The article is a beautiful essay by the Netziv, related to the reasoning for Korbonos.[9]

The Netziv begins his article with the following sentences:

הגיעני מווילנא על ש”ק שני עלי לבנון משנת ששית. וקראתי לשבת עונג מפרשת העלים ומדברי מע”כ שי’ המפקידים חן ודעת שכל טוב. ובהגיעי לנו 2 בבשורת סי’ הזכרון להריטב”א ז”ל נרגשתי במה שהעיר חכם א’ מעצמו וגם בשם האברבנאל ז”ל השגה…

In 1993, this article was reprinted in the previously mentioned new edition of the

Meishiv Davar (5:90). While they do cite that the source of this article is from the

Ha-Levonon (but not an exact location) the first three lines I just quoted are missing and the piece begins with the words נרגשתי במה שהעיר חכם א’

Rabbi Chaim Berlin and Reading Newspapers in general:

In a letter[11] to Avraham Eliyhau Harkavy he writes:

האמנם כי מתענג אנכי לעתים, למצוא את דברי חכמת, המאירים כספירים, על דלתי מכה”ע השונים, וגם בספרים מיוחדים, יקרים מפנינים, אבל משנה שמחה הי’ לי הפעם, בשלח ידידי את הספר, לי לשמי, וארא, כי כמוני כמוהו, עודנו זוכרים איש את רעהו, וכי נאמנו דברי המלך החכם, כי כמים הפנים, כן הלבב, ואהבה טהרה ונאמנה לעולם עומדת [שנות דור ודור, א, עמ’ קצט (=נשמת חיים, מאמרים ומכתבים, עמ’ שלט)].

Elsewhere he writes:

הן ראיתי את הרב מי’ שאול הכהן קאצענעלינזאהן, עומד על המצפה, בצופה נומר 30… [אוצר רבי חיים ברלין, נשמת חיים, א, סי’ רח].

הנני להודיע לכבודו את הרשום אצלי… אשר זה מקרוב גמגמו מהבנת לשונו גדולים חקרי לב העומדים על המצפה בצופה להמגיד שנה זו… [נשמת חיים, סי’ קצט].

Although Rabbi Chaim Berlin read newspapers he writes:

את העלה ממכתב העתי ההולאנדי הגיעני, ואם כי עלי להודות לו כי חובב הוא את דברי לפרסמם ברבים בשמי, בכל זה האמת אגיד לו, כי אין דעתי נוחה כל כך מהדפסת דברי תורה במכתב עתי, מטעם המבואר בפ”ק דרה”ש יח ב’ שבטלו חכמים להזכיר שם שמים בשטרות שלמחר נמצא שטר מוטל באשפה. ומי לא ידע, שמכתבי העתים מסוגלים לזה, שלוקחים אותם בחניות לכרוך בהם כל מיני סחורות וכדומה ולמחר מוטלים באשפה ח”ו על כן לא ירד בני בזה [אור המזרח, לה:א (תשמ”ו), עמ’ 44-45 (=ר’ אליעזר ליפמן פרינץ, פרנס לדורו, ירושלים תשנ”ב, עמ’ 326-327 ; נשמת חיים, מאמרים ומכתבים, עמ’ קסט)][12].

The Netziv writes about printing newspaper articles in Torah:

טרם אענה אני אומר, שאין הדבר נוח לי לפלפל בד”ת בעלי עתים, וכבר אמרו חז”ל חמוקי ירכיך נמשלו ד”ת לירך מה ירך בסתר אף ד”ת בסתר, ורק בראותי דבר מפליא שהיה אפשר להרבות ממזרים בישראל ח”ו, ראיתי חובה להודעי במקום רבים כי אין זה הוראה אלא טעות… (אגרות הנצי”ב ממלאזין, עמ’ נז).

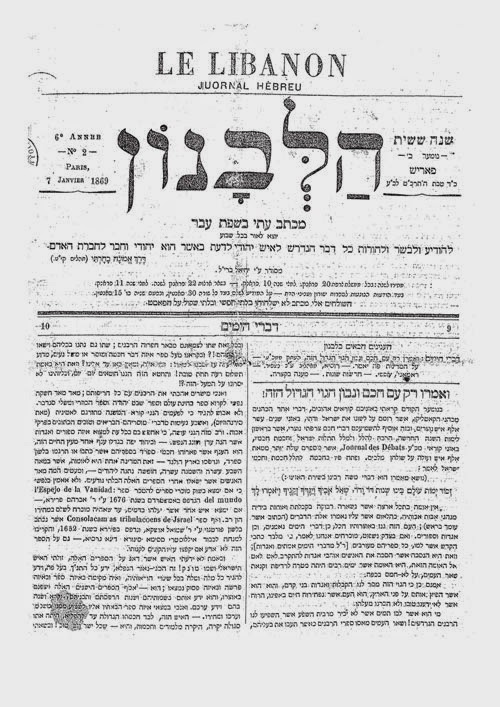

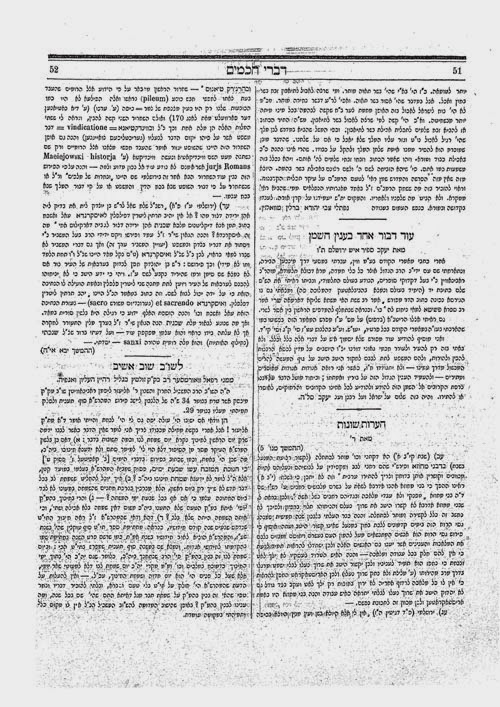

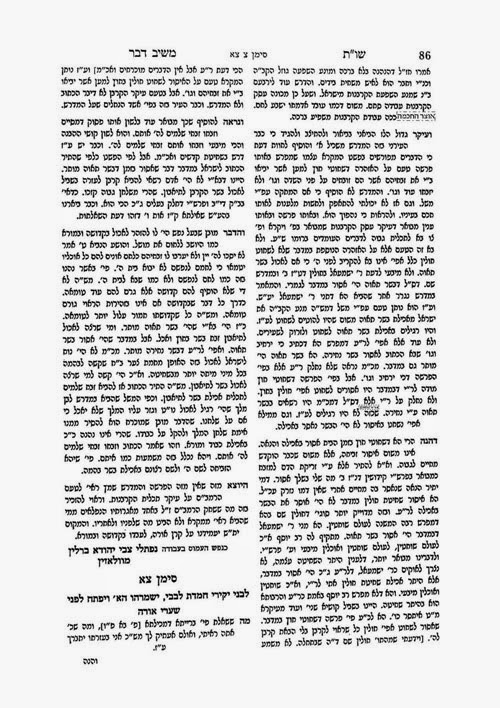

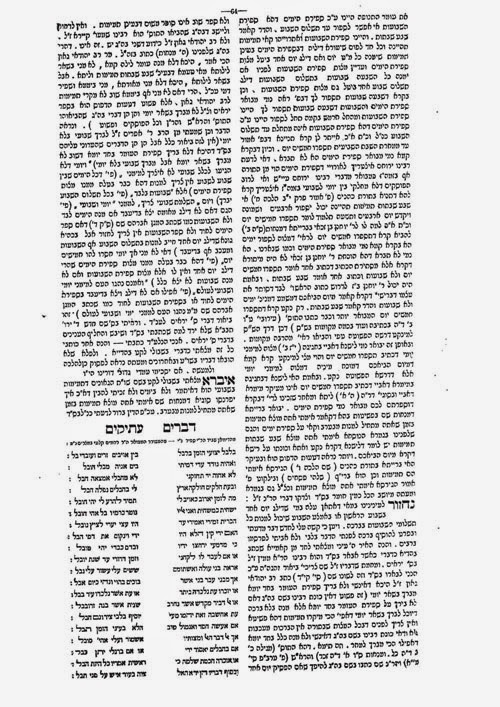

Newspaper articles by Rabbi Chaim Berlin:

Although it appears from the above quoted letter that Rabbi Cham Berlin was against writing newspaper articles, we do find that he did write some. For example:

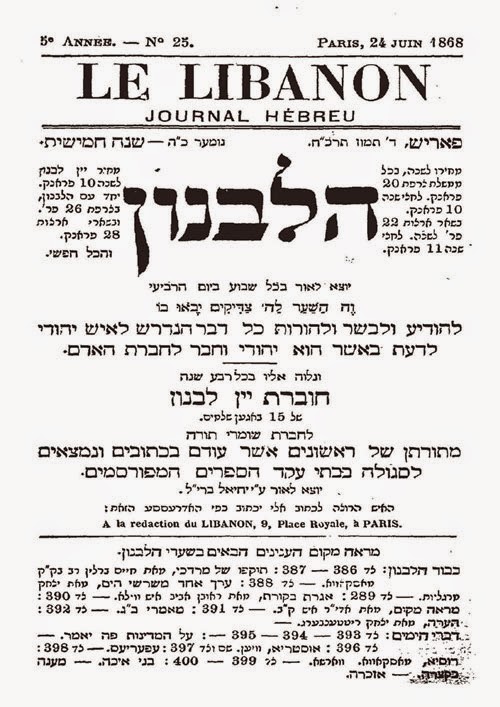

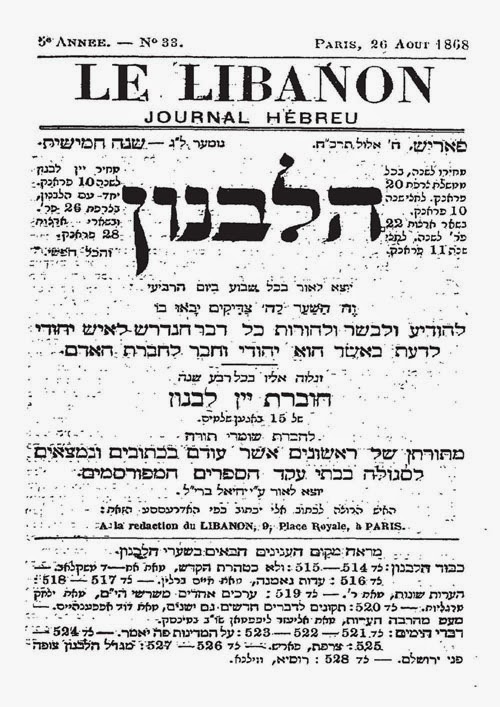

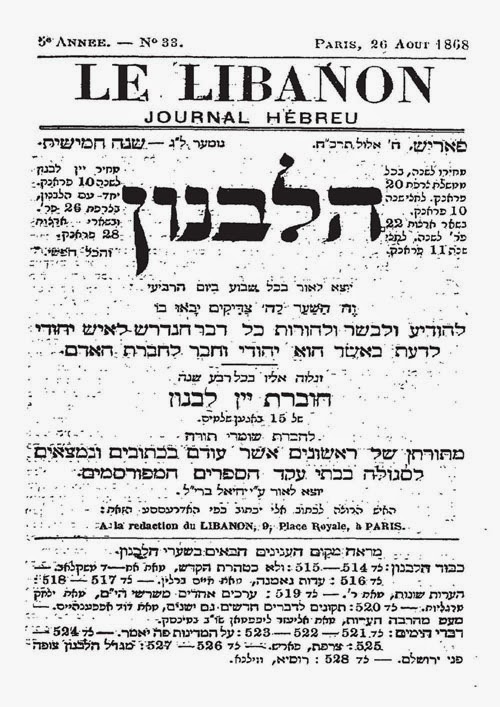

In the June 24, 1868 issue of

Ha-Levonon we find an article of Rabbi Chaim Berlin.[13]

A few months later in the August 26, 1868 issue

Ha-Levonon we find another article of Rabbi Chaim Berlin.[14]

It could be that he wrote those two articles as they were important issues but in general he did not write articles of Random Torah.

However, in 1863, the Newspaper

Ha-Levonon‘s first year, in the ninth issue we find a nice long article from Rabbi Chaim Berlin related to

Sefirat Ha’omer. Rabbi Berlin comes to the conclusion if one forgot to count

Sefirah one night so although the next night he cannot count the days with a

Beracha he may count number of the weeks with a

Beracha!

In the 1993 edition of the Shut Meishiv Davar, after reprinting this piece by Rabbi Chaim Berlin, they print a letter that the Netziv wrote to him on the subject.

בבואי ראיתי ביד חתן גיסי… שי’ עלה לבנון… מכתבך בראש הלבנון עולה על שלחן מלכי רבנן… הוספתי גיל לראות כי מצא בני מחמדי שליט”א להפיץ תורה בישראל, אף כי להגיד בראש הלבנון הוראה למעשה, יוסיף ה’ לאמץ חילך ולבבך בני להגדיל תורה בלי לב ולב עקוב את המאושרה, ואז תעש חיל וגבורה.

אמנם בני שמתי עין העיון בדבריך האוהבים… אחר כל זה תשכיל כי שגגתם בהוראה… ולא יפול לבבך על זה בני יקירי. וכבר אמרו ז”ל והמכשלה הזאת תחת ידך כו’ כידוע… והנני מוסיף בזה דבר… אם אתה נכשל בהוראה אזי הוא תחת ידיך להתבגר על התשוקה לקיימה ולהחזיקה ולעשות סניגורין, אלא אתה מודה על האמת דברים שאמרתי טעות הן בידי או אז ודאי ראוי להוראה בישראל. [משיב דבר, ה, סי’ טז].

Rabbi Rafael Shapiro, brother in law of R’ Chaim,[15] also argues on this Pesak and begins his Teshuvah as follows:

הן הגיעני זה כשתי שבועות עלי הלבנון נו’ ט’ שם ראיתי את חידושיו… ולדעתי לא כן ידמה…

R’ Chaim’s great-uncle, Rabbi Meir Berlin, also has a Teshuvah on the subject. He takes issue with R’ Chaim’s Pesak, begining his teshuva stating:

הובא לפני עלה א’ מלבנון… [אוצר רבי חיים ברלין, שו”ת נשמת חיים, א, עמ’ שיב-שיד].

In his memoirs about Volozhin, a student writes:

בנו הרב הגא’ ר’ חיים ברלין שנתמנה אחר זמן לרב במסקבה היה כותב במ”ע מאמרים על דרך השכלה והיה סופר מצוין בכתב ולשון ארמית שכתב בה מאמרים על טהרת לשונה… [משה יאפעט, רשומות וזכרונת, קובנה תרפ”ד, עמ’ 10]

Rabbi Chaim Berlin and Reading Newspapers on Shabbas:

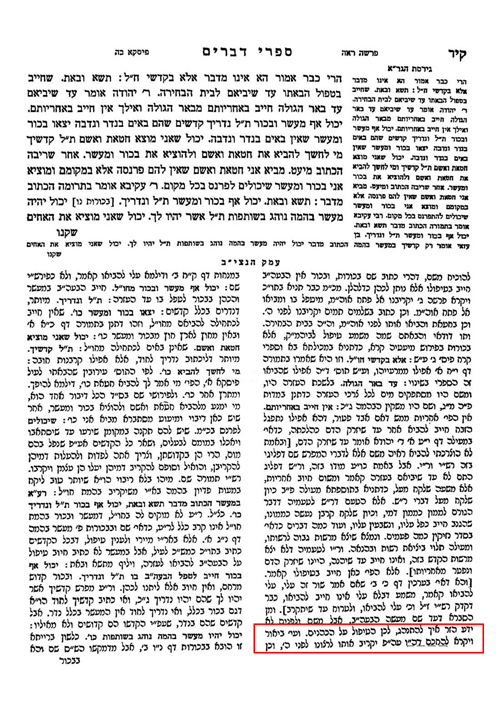

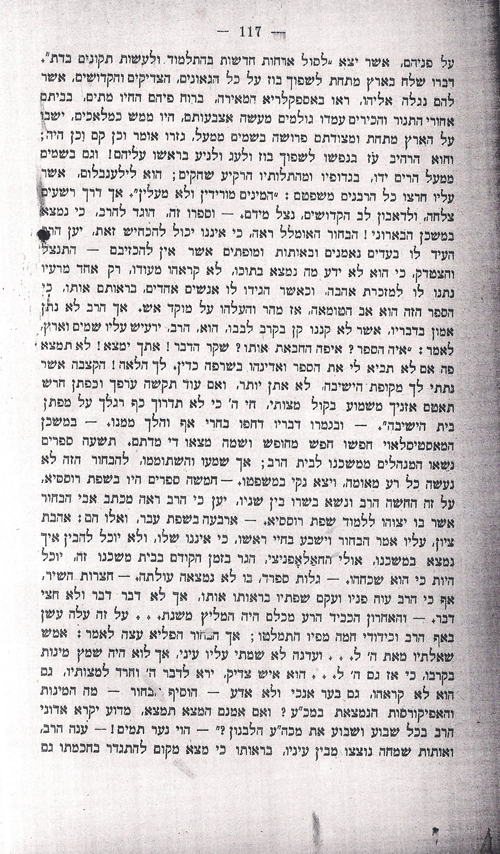

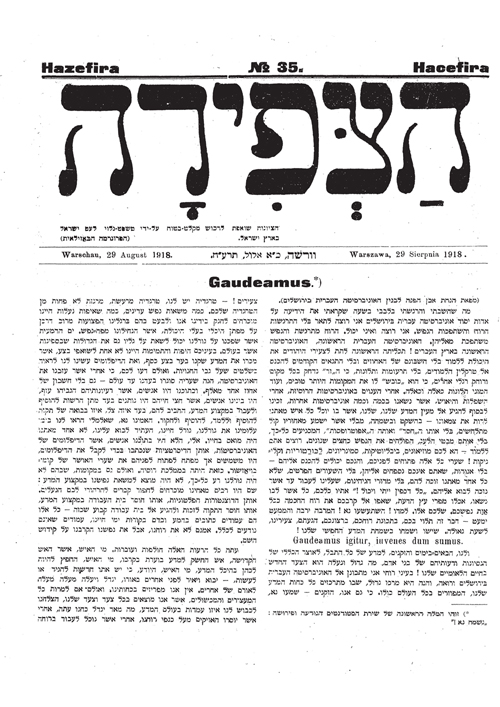

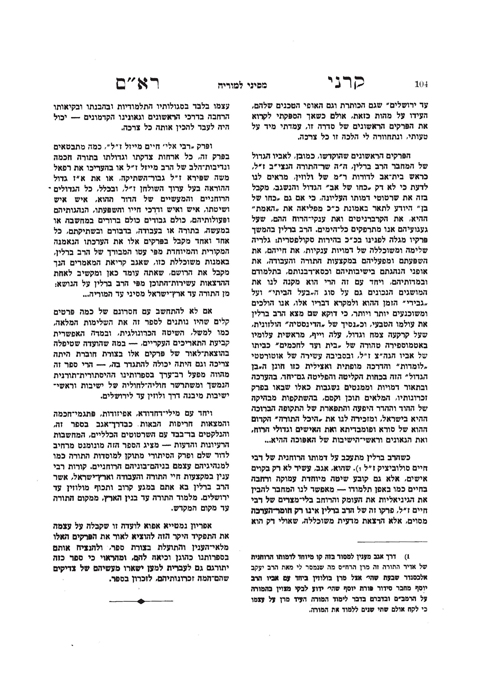

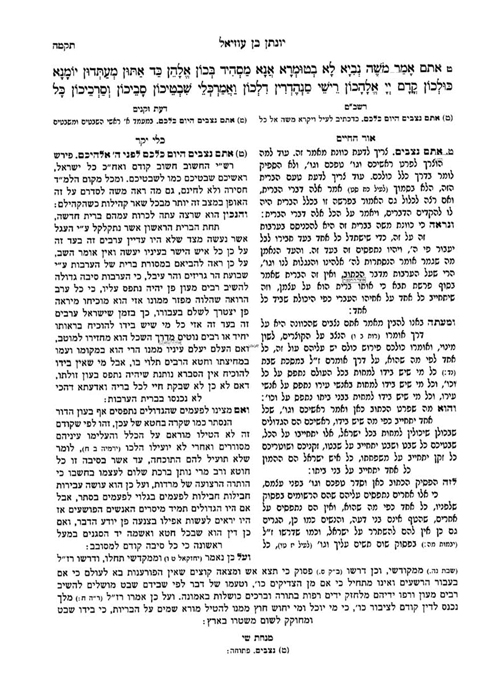

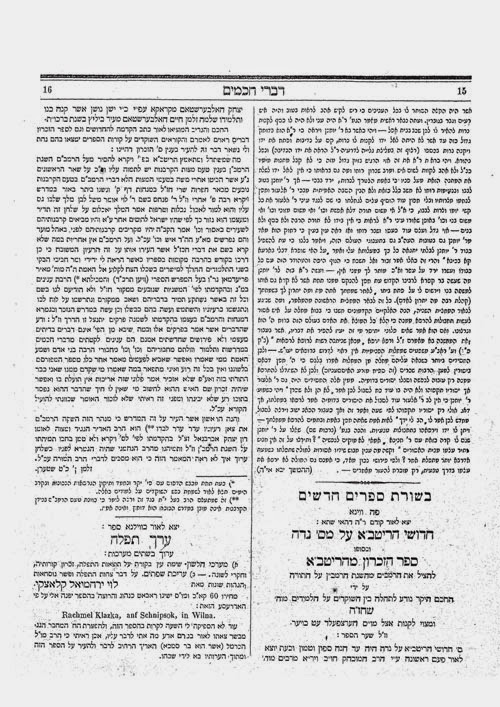

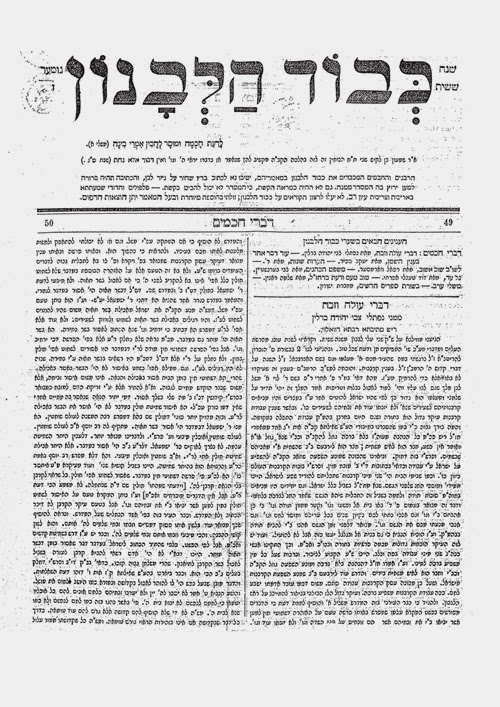

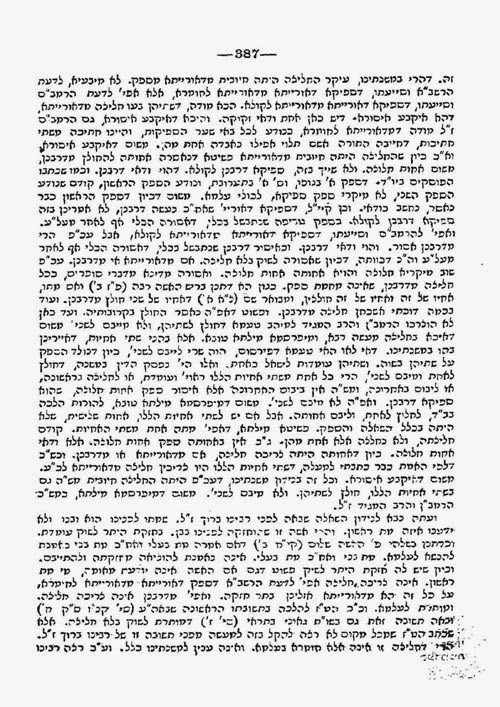

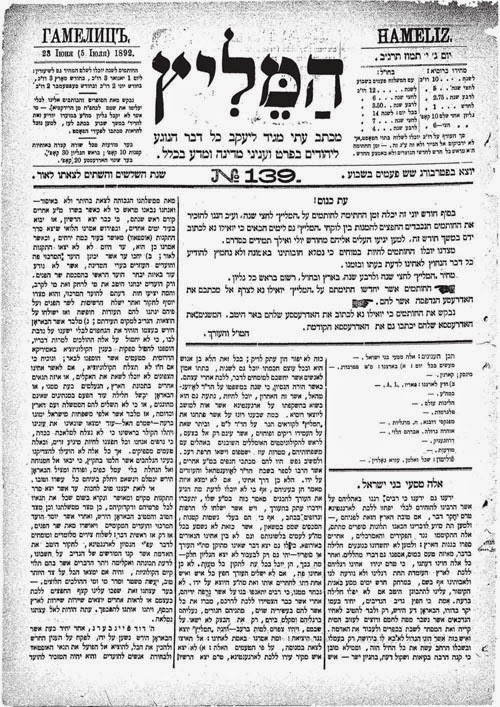

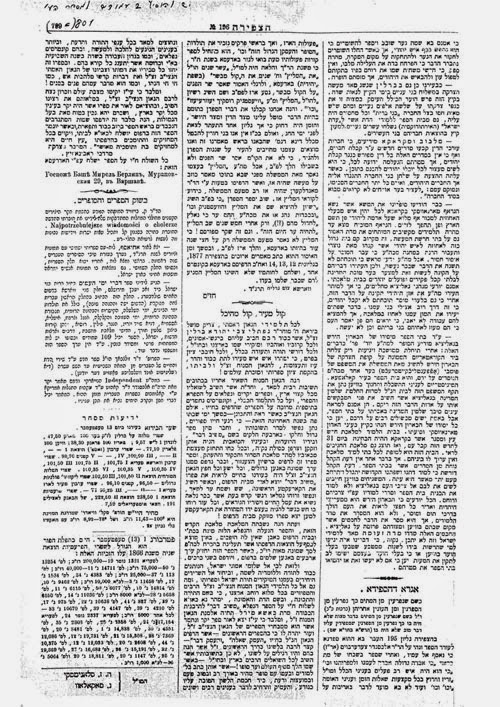

Printed in Igrot HaNetziv Me-Volozhin is a letter by Rabbi Chaim Berlin, dated Sunday 1892.[16] In the letter he writes as follows:

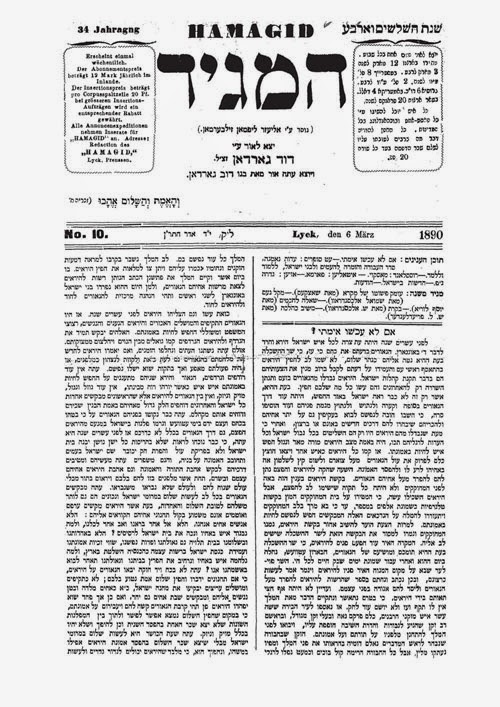

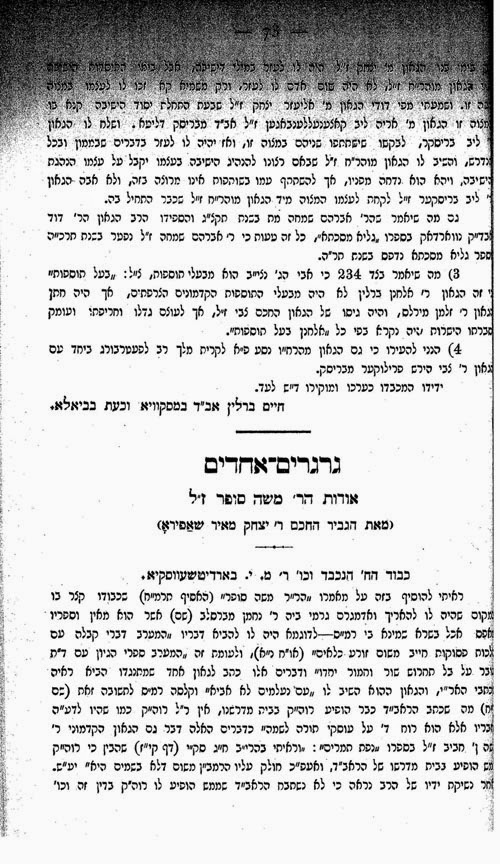

בשבת אתמול בסעודת ש”ק [=שבת קודש] בחברת מרעים כבדים, אהובים וידידים, רבנים מצוינים, וגבירים אדירים, עלה לפנינו עלה מכה”ע [=מכתב עת] המליץ, מיום ג’ העבר, נו’ 139, ושם נאמר…

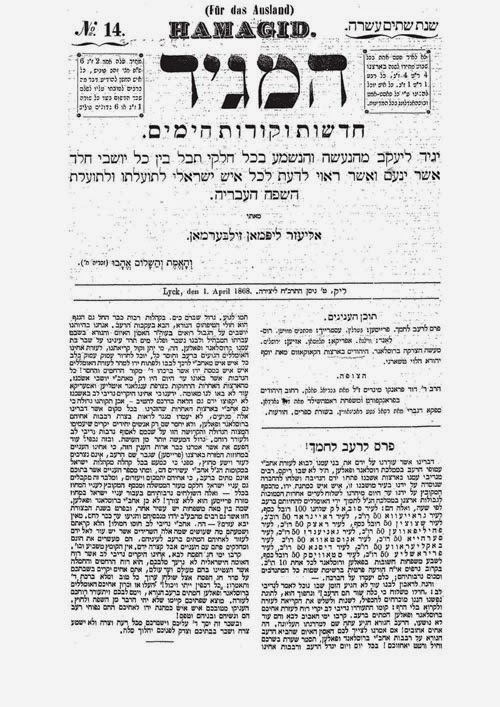

Here is an image of the Newspaper that they were reading:

Additions to note six about the Journal ‘Ittur Sofrim’: I should have mentioned that the Netziv was not happy about it at first, as he thought it would take away too much time from Rav Kook’s learning.[17]

Worth pointing to is Berdyczewski’s quote from the Netziv when he was asked about starting a Torah Journal for the Bochurim to print some of their ideas

דכירנא כד הוינא בהישיבה, התעוררו הרבה תורנים משכילים ליסד מכתב עתי תורני, אשר בו יבואו חידושים כתובים ברוח הגיון, כללים הנמצאים בש”ס, מאמרים העוסקים בחכמת ישראל וספרותו, וכשאר באו להנצי”ב לבקש כי ישתדל בעדם רשיון הממשלה על זה אז גער בהם פן… התעדו קוראים נכבדים מה הוא הפן הזה? לא דבר אשר יכול להורס חלילה את מוסדי הישיבה מהשקידה הגשמית, על ידי עסקם בכתיבה… [הכרם תרמ”ח (=כתבי מיכה יוסף ברדיצ’בסקי, א, עמ’ 97]

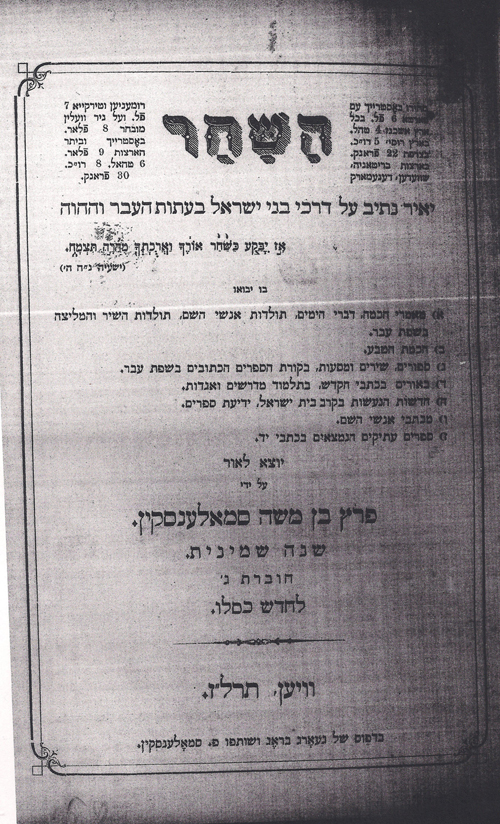

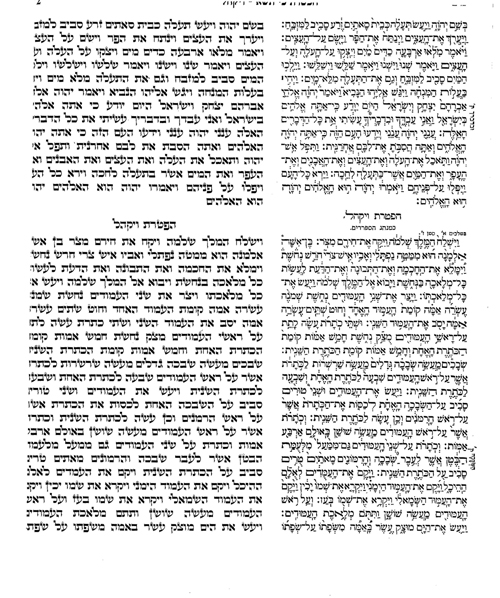

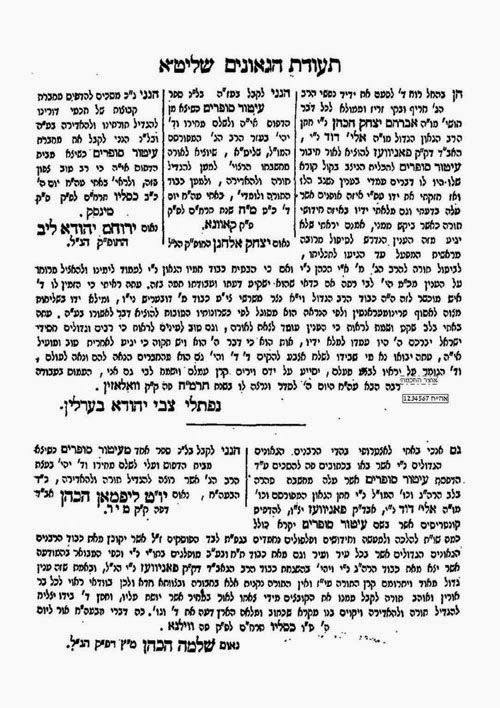

As one can see from the Netziv’s Haskamah to Ittur Sofrim here:

Rabbi Aaron Felder writes that he once asked Rav Moshe Feinstein about Rav Kook, to which Rav Moshe responded:

שבצעירותו היה הרב קוק אורך של ירחון תורני, והיו טוענים מכיריו שאין ראוי לאדם גדול שכמותו להיות אורך ירחון ומבחינת שאינו לפי כבודו [רשומי אהרן, א, עמ’ כח].

Moshe Reines wrote in an article in the journal Beis Hamedrash printed in 1888:

גם חסרון ספ”ע מקדש לתורה ולהגיון לחקירה ולבקרת הוא חסרון מורגש בספרותנו, אולם החסרון הזה ימנה כנראה בקרוב, כי הנה הרה”ג ר’ אברהם יצחק הכהן קוק רב בעיר זימעל… אומר לה”ל מכ”ע חדשים כזה בשם עיטור סופרים, המקדש לתורה ולתועדה, וכבר נתנה החברת הראשונה בדפוס נחכה נא ונראה היצליח ד’ את דרכו אם לא [בית המדרש 1888, עמ’ 86].

See also R. Shmuel Alexandrov, Michtavei Meckar Ubikurut, 1, Vilna 1907, p. 7; R’ Mordechai Gimpel Yoffe’s letter to Rav Kook in Igrot LiRaayah, p. 17; R’ Kluger’s letter Ibid, pp. 26-27; Y. Mirsky, Rav Kook, Mystic in a time of Revolution, pp. 20-21.

Addition to note seven: The new version of ‘Ittur Sofrim’ does not say where their copy of Rav Zev Turbavitz’s letter about the Heter of the Netziv is from.

Rabbi Baruch Oberlander sent me a reference to Rav Zev Turbavitz’s Shut Tifres Ziv (1896), pp. 51-55 where he has a lengthy Teshuvah about reading newspapers on Shabbas in the beginning he writes:

אמנם כעת יצא לאור ספר אחד ראיתי בו מכתב מאחד מגדולי הזמן שהביא….

In this Teshuvah he does not write the Netziv’s name nor the journal’s name nor does he write as sharply as he does in the letters I quoted from him to the Aderet and Rav Kook. But he does take strong issue with the Netziv’s Heter, going through the Sugyah at great length.

Addition to note eight: Both editions of Rabbi Chaim Berlin’s Teshuvot fail to mention the source of this Teshuvah; it’s printed in the back of the Shut Bikurei Shlomo (1:321). See also Shut Nishmat Chaim, p. 343, where he mentions he printed the Teshuvot found in Shut Bikurei Shlomo but he does not say where he did so.

Addition to note nine: The reference Shut Bikurei Shlomo siman, 3-4 includes a Letter of Rabbi Yehosef Zechariah Stern on this topic. In the new edition of the Shut Zecher Yehosef printed by Mechon Yerushalyim (2014), they reprinted this Teshuvah with many additions (2, pp. 437-440) from the notes of R’ Stern which he wrote on the side of his copy of Shut Bikurei Shlomo.

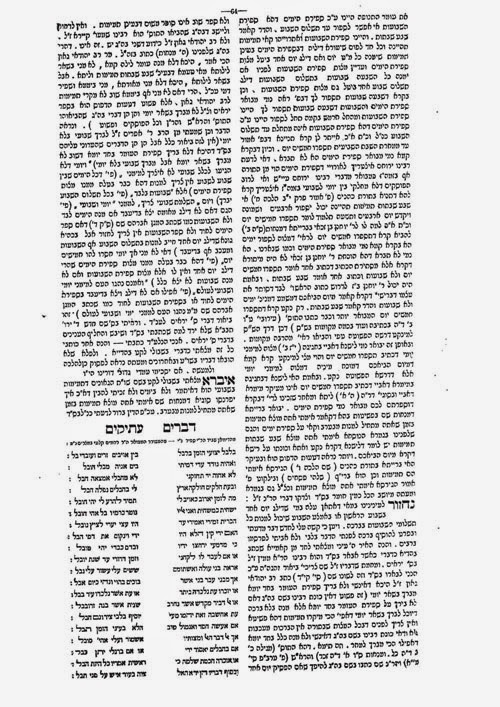

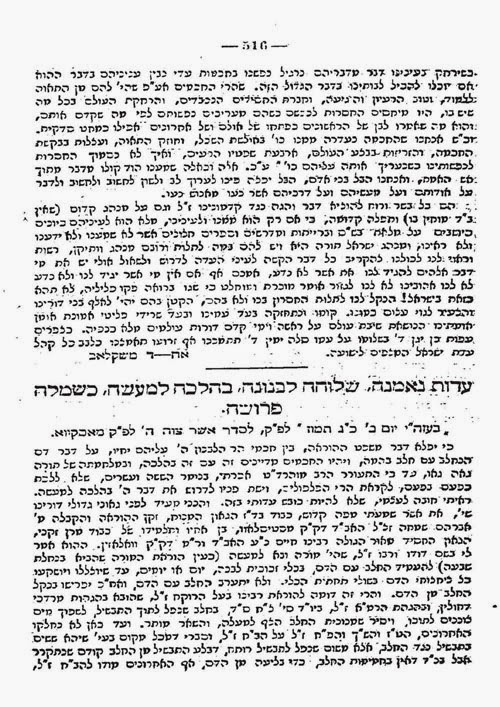

Who censored the 1894 edition of the Meishiv Davar?

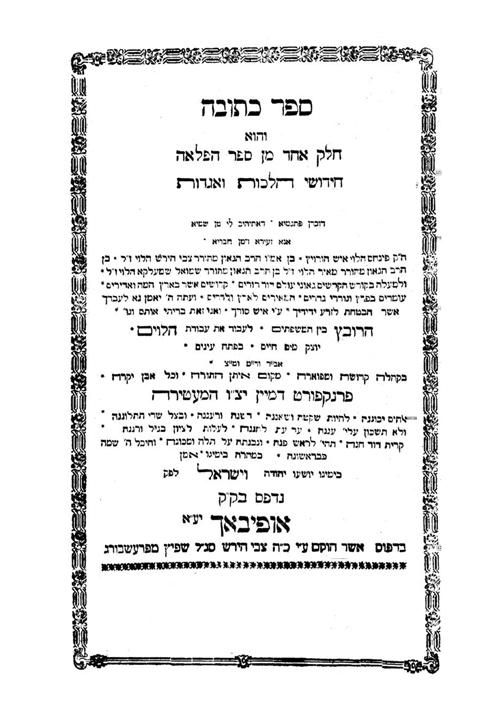

In the Shar of the Sefer of both editions it says it was printed:

בהוצאת אשת הגאון זצלה”ה ובניה

I am not sure how much the sons Meir and Yakov had to do with the printing. Meir was fourteen years old at the time and Yakov was about seventeen[18].

R’ Chaim Berlin wrote to Rabbi Eliezer Lipman Prins:

מכ”י מר אבא הגאון החסיד זצלה”ה נדפס אחר פטירתו, שו”ת משיב דבר ע”י אלמנתו, הדרה בוורשא, ואך ממנה יכול רום מעלתו להשיגו, על פי האדרססא שארשום בשולי מכתבי, ובידי לא נמצא כי אם ספר אחד למעני [אור המזרח, לה:א (תשמ”ו), עמ’ 44-45 (=ר’ אליעזר ליפמן פרינץ, פרנס לדורו, ירושלים תשנ”ב, עמ’ 324; נשמת חיים, מאמרים, עמ’ עח)].

I would say the Netziv’s wife had much more to do with the printing than her sons, however I do not think that Batyah Mirel Berlin[19] was the type to censor such a thing. According to her granddaughter’s description of her:

בשעות הפנאי המעטות שלה עיינה סבתא בעיתונים ובספרי הקודש בחומש ובנביאים, בהם הייתה בקיאה למדי [טובה ברלין פפיש, ספר וולוז’ין, עמ’ 481 (= צלילים שלא נשכחו, עמ’ 55)].

Furthermore her father the author of the Aruch Hashulchan writes:

נ”ל דכתבי העיתים אינם בכלל זה ומותר בחול לקרותן שהרי הם מודיעים מה שנעשה עתה וזה נצרך להרבה בני אדם לדעת הן במה שנוגע לעסק והן במה שנוגע לשארי עניינים אבל עניינים שכבר עברו מן העולם מה לנו לדעת אותם וכן כל דברי הבלים שיש בהם שחוק וקלות ראש וק”ו דברי עגבים עון גדול הוא ובעוה”ר נתפשטו עתה בדפוסים ואין ביכולת למחות בידם (ערוך השלחן, סי’ שז ס”ק ט).

Here is an advertisement published shortly after the Netziv died, asking for financial assistance for completing the printing of the Meishiv Davar.

Appendix Two:

[4] A facsimile of one of the Netziv’s letter to him was reprinted in volume one of the collection of Berdyczewski writings, Kesavim 1,(1996) p.64.

[7] כנראה לכולל ברודסקי. לתקנות הכולל ראה: ר”מ רבינוביץ, ‘תעודות לתולדות הישיבה בוולוזי’ן’, קבץ על יד (תשי”א), עמ’ רלא; ת’ פראנק, תולדות בית ה’ בוואלאזין, ירושלים תשס”א, עמ’ 118 ואילך. על פי התקנות, בכל תקופה נבחרו עשרה אנשים לכולל. שם, עמ’ 121, פורסמה רשימת הנבררים משנת תרמ”ז ואילך, ושם מבואר שכבר היה עשרה אנשים בהכולל [הערת ידידי ר’ שלמה הופמן].

[10] After patting myself on the back for this discovery, I found this source, in the name of Dr. Leiman, buried in a footnote in Jacob J. Schacter’s classic article “

Haskalah, Secular Studies and the Close of the Yeshiva in Volozhin in 1892“,

Torah u-Madda Journal 2 (1990), on page 126, footnote 105. However they do not note the censorship from the 1993 edition of

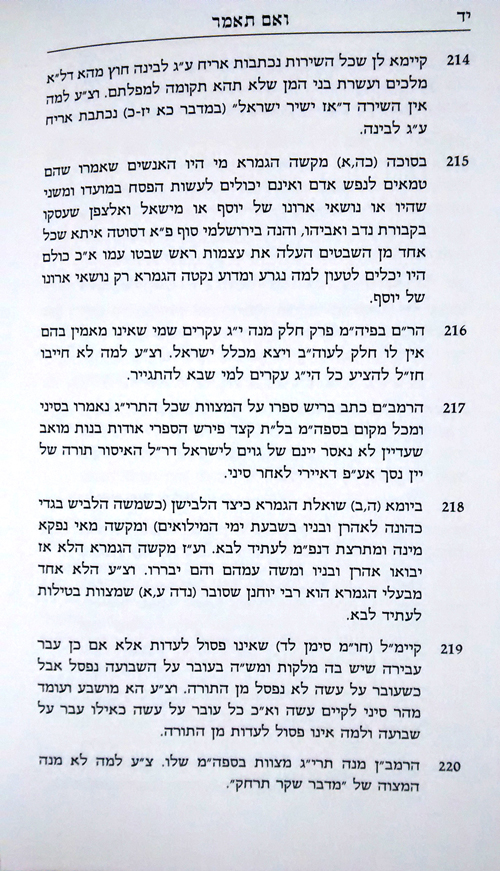

Meishiv Davar, as this article was printed in 1990.