Racy Title Pages Update II

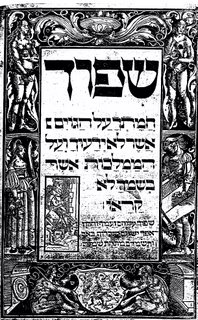

While I do not intend to focus solely on racy title pages, I do have a futher update to my previous posts I, II. It appears that the title page used in the Levush (Prauge, 1590) was actually a recycled page. It was first used in the Prague 1526 Haggada.

While I do not intend to focus solely on racy title pages, I do have a futher update to my previous posts I, II. It appears that the title page used in the Levush (Prauge, 1590) was actually a recycled page. It was first used in the Prague 1526 Haggada.

Now aside from this page, which we have seen is objectionable to some today, there were other objectionable illustrations in this edition. Yerushalmi in his Haggadah and History, notes that there was an illustration accompaning the verse found in haggadah from Exekiel 16:7. That verse reads “I cause you to increase, even as the growth of the field. And you did increase and grow up, and you became beautiful: you breasts grew, and your hair has grown; yet you were naked and bare” Accompaning this verse the following illustration appeared, which as you can see, really just shows just what the verse describes.

Now in the Venice 1603 they wanted to illustrate this verse, however, they did not want to use a nude, so they replaced it with a picture of a man, which of course, has little to do with the verse. In fact, they felt the need to place a legend on the picture so the reader would not be too confused the legend reads “A Picture of a Man!” (on the right)

Racy Title Pages Updated

As I had previously noted, many older seforim include what may be deemed objectionable by today’s standards. I had mentioned how one book had attempted to rectify this, the new edition of the Levush. In this edition the title pages from some early editions of the Levush are included in the introdoction, however the title pages has been “touched up.” Now that I have learned how to include images, I present both the original and the touched up version.

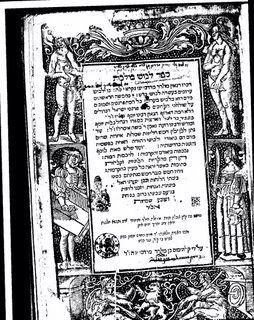

Although, the publishers of the Levush decided to alter the original, the new edition of the Tashbatz Koton did include a reprint of the first edition (1556) with the original title page unaltered. However, as is apparent, there are images on this title page that some might find objectionable.

[Unfortunately, I can’t get the pictures to layout nicely, if someone knows how to fix that please let me know]

Differences btwn the “Improved” Making of a Godol and the Original

by Dan Rabinowitz

As previously mentioned at the Seforim blog, Rabbi Nathan Kamenetsky’s Making of a Godol has been reprinted in an “improved” edition. In the new edition there are a few significant changes, which appear to have been done to appease those that originally banned the original.

It is fairly easy to find these changes with the help of the index in the “improved” edition.

Here are some of the highlights of these changes:

First Edition (“FE”) – Also like my father, R’ Aaron Kotler dabbled in secular studies at this time. He was more interested in literature than in the sciences which attracted my father’s interest. (305)

Improved Edition (“IE”)- Like our protagonist, young Aaron Pinnes picked up some secular knowledge as an early teenager in Minsk. (305)

FE- . . . during a visit with a young, intellectual protege of the Hazon-Ish who headed a yeshiva in Ramalah, R’ Aaron blurted out, “This was expounded by Aleksander Pushkin” (305)

IE- not there

FE- nothing

IE- A story how he utilized this youthful experience to benefit the Torah community in Israel, came to light in an interview with R’ Dov-Tzvi Rothstein.

FE- nothing

IE- In the Talmudic Yeshiva of Philedelphia mail is censored till this day: the students are “appeased” by being told “Without censorship, R’ Aaron Kotler would have been lost.”

FE- It maybe postulated that R’ Aaron had too much self-confidence, as per what . . .

IE- In my fater’s opinion, R’ Aaron had very definate self-confidence, as per what . . . (386)

FE- “What is the difference? Before you go to his [R’ Aaron Kotler’s(D.R.)] yeshiva, you don’t know how to learn anyway; and after you have been there a bit, you will already be considered [by him] that you do know how to learn. . . ” Then our protagonist mitigated the seemingly sarcastic remark by explaining

IE- What is the difference. . . [same as above D.R.] Then our protagonist went on to explain his words by adding.

FE- the Lithuanian government issued an edict saying that the students of any yeshiva without secular studies would no longer be eligable for draft deferments. At a rabbinical assembly called to discuss the issue, it became evident that the Telz Yeshiva was ready to bow to the order, while the Slabodka Yeshiva, . . was uncompromisingly opposed. (510)

IE- the Lithuanian . . . eligable for draft deferments. Only the Telz Yeshiva , which despite opposition had started a mekhinah (preparatory school) with secular studies recieved recognition.

FE/IE There are a couple minor changes on 510-13 not worth getting into here

While there are numerous other changes, the above represent the “most controversial” passages from the first edition, and how they appear in the current edition.

“Improved” Making of a Godol

In this new edition, there is a helpful index which shows what exactly has been improved upon. According to the index only one story has been removed in it’s entirety. That story, in which R. A. Kotler responded to an interruption during his shiur from a “red-bearded scholar.” R. Kotler responded by saying “Red Heifer, be still!” This was removed due to the source of the story. Apparently, the source for this particular story did not support R. Kamenetsky when R. Kamenetsky questioned the validity of the ban, and thus R. Kamenetsky did not want to include this persons comments.

According to the index there are no more omissions in this new edition. Instead, there are numerous elaborations, corrections, and a significant amount of new information. R. Kamenetsky states in one of the first “elaborations” that “the unexpected ban issued on the original, unimproved, version” helped the current edition be of value for all time.

unfortunately, this improved edition still suffers from a serious lack of editorial oversight. Although, the book has been altered to conform and appease those that issued a ban, it was not altered to make it more reader friendly. The improved edition still utilizes the same format of text followed by excursuses with numerous footnotes and tangents. It still requires, as R. Kamenetsky points out, a pencil and paper to be able to be able to flip back and forth through the book and keep track of what page one is on.

There is one important addition to the book, while not solving all the difficulties, at least alleviates some of them. R. Kamenetsky included a timeline line which tracks both significant events in world history with a parallel timeline that tracks significant Jewish events. When the Jewish events appear in the book, R. Kamenetsky included a footnote to alert the reader which page they can be found on. This allows, if one so desires, to read the book in a chronological order.

Although, the original book was only $40 (when it was published, subsequent to the ban the book was selling and continues to sell for outrageous prices) this improved version is $125. I assume that the steep raise in price was to allow for R. Kamenetsky to recoup some of his losses he suffered from the first edition. There were only 1,000 copies of the first edition published, however, R. Kamenetsky stopped selling and ordered his distributor to stop distributing them once the ban was pronounced. While it is impossible to know with certainty, this probably left him with numerous unsold copies thus causing significant loss. R. Kamenetsky implemented this policy even though he stood to profit immensely from the ban, he has said he felt bound by the ban even if he felt it was unjust.

New Book Censored

This book also contains an index as well as the Iggeret Pri Megadim from R. Yosef Teomim. This letter is typically published at the beginning of his commentary to Orakh Hayyim, however, due to the fact that he a) advocates for the study of R. Elijah’s books; and b) has numerous comments on the Sefer haTishbi, this was included here. There is also an index of just these letters.

Now, on to the controversial portion of the book. This book also contains the critique of R. Shlomo Schick on the Sefer haTishbi. R. Schick, in his commentary on the Torah, Torah Shelmah (1909, Satmar) takes issue with many of R. Elijah’s statements, not just his Sefer haTishbi. However, the editors of this edition of the Sefer haTishbi have collected R. Schick’s comments that relate to the Sefer haTishbi. The editors have also included a rebuttal of R. Schick titled Tzidkat haTzadik.

While this may seem rather innocuous, R. Schick is considered in some circles to be unacceptable. This is especially true amongst the Hungarian Haredim. R. Schick, who was a Rabbi of what was known as a Status Quo community in Hungary, was himself a Haredi. However, he felt that instead of alienating his community and many others in Hungary he would take a more reconciliatory stance. This put him in conflict with the majority of the Haredim in Hungary. They wanted to cut off all the non-Haredim. In fact, they issued an edict that all shecita by members that considered themselves Status Quo, was to be considered non-kosher. Importantly, many in the Status Quo community kept Torah and mitzvot a fact R. Schick pointed out in many of his teshuvot. This placed Schick outside the camp of the “frum” and thus among some his writings are unacceptable.

Therefore, there are two editions of this newly reprinted Sefer haTishbi. One that contains an actual photocopy of the haskama of the Betaz of Jerusalem and a second version that does not. In the edition that contains the haskama both the comments of R. Schick as well as the rebuttal does not appear. In the edition that does not contain the haskama you get what I described above, the comments of R. Schick and the editor’s rebuttal.

The editors even note this in the edition that contains R. Schick’s comments. They explain that the Betaz gave them a haskama (they even quote it but do not reproduce the actual letter, so they get to say they got the haskama without offending the Betaz) but that the Betaz told them they found R. Schick to be unacceptable and thus would not want to give a haskama to such a work.

Therefore, one now has a choice between the Betaz haskama or the comments and rebuttal of R. Schick.