In the Jewish liturgy there is a fundamental question dealing with the composition of the Hebrew found therein. There are two major types of Hebrew – Rabbinic and Biblical. The question becomes which should one be using when praying. This at first blush may appear to be of minor significance, however, most controversies regarding various words throughout the prayer book can be traced to this one point. This issue of which Hebrew to follow was brought to head in the 18th century. During this period there were a few books published dealing with the proper nusach (composition of the prayers). Some of these works advocated for various changes in the prayer book based upon the authors understanding of which Hebrew to follow when praying. This in turned provoked a fairly large controversy which can be felt today by anyone sensitive to the nusach of the prayers.

Today, although most may be unaware, many changes effected during the above referenced time period are still to be found in almost all the standard prayer books. This is so, as Wolf Heidenheim in his prayer book, which became the standard for most which followed him, relied and incorporated numerous changes based upon these 18th century works. Heidenheim’s book became, in part, the standard after he was able to secure an approbation from one of the most traditional Orthodox rabbis of the day – R. Moshe Sofer (Hatam Sofer). R. Sofer, whose well known statement “anything new is prohibited” was either unaware of the “newness” of Heidenheim’s work or perhaps agreed with his alterations, ensured Heidenheim’s work would become the exemplar for all subsequent prayer books.

One of the more interesting books to come out of this period has recently been reprinted. This book, Yashresh Ya’akov, was originally published around 1768 and, according to the title page, was authored by R. Ya’akov Babini. The work is supposedly based upon a question which R. Babini was asked. Specifically, someone wrote that he entertained an Italian guest. This guest when it came time to say birkat hamazon (grace after meals) said the prayer with numerous changes from the standard format. The host wrote to R. Babini to ask whether these changes were in fact correct. All of these changes are more or less based upon the notion that one should follow the Biblical Hebrew as opposed to the Rabbinic Hebrew. R. Babini defends the guest’s alteration and demonstrates that in each instance the changes were correct.

That is the basic background on the book. Yet, there are numerous other important facts that are not necessarily apparent from just a casual read of the book. First, as I mentioned, taking a position that Biblical Hebrew is the correct Hebrew and thus one should alter the standard was highly controversial. In an effort to avoid controversy the true author of the book – not R. Babini – hid his name. The true author is really R. Ya’akov Bassan.[1] R. Bassan gave an approbation to this work although he did not use his own name as the author. Instead, R. Bassan picked someone who had less than a stellar reputation – R. Babini. R. Babini in 1759 published a book under his own name titled Zikhron Yerushalayim which listed various holy places in Israel as well as where certain Rabbis are buried in Israel. R. Babini, neglected to mention in this publication that this work had already been published in 1643 under the very similar title Zikhron B’Yerushalayim, which contains, with minor changes, the very same text R. Babini offered as his own. Thus, looking for a patsy, R. Bassan picked someone who already did not have such a great reputation. R. Bassan although unwilling to offer his name to his own publication decided to instead offer his approbation to his own work.

Aside from hiding the authorship, the place of publication was also altered. The title page reads Nürnberg as the place of publication. This is incorrect, in actually this was published in Altona. The date on the title page reads 1768, however, the date on the approbation reads 1769 thus making the date offered an impossibility. All of these “hints” should lead an observant reader to realize something funny is going on here – namely nothing is what it appears. These types of hints to the ultimate author were actually somewhat commonplace during this period. Most famously, R. Y. Satnow would publish books not under his own name, instead either in the approbation or the title page he would offer hints that only an astute reader would notice demonstrating that R. Satnow was in fact the true author.[2]

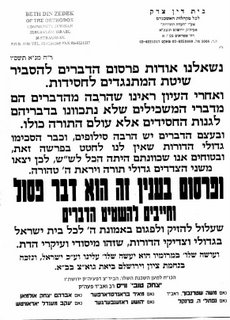

As R. Bassan correctly surmised, his work was in fact controversial. R. Binyamin Espinoza wrote a work directed at disproving the underlying premise of R. Bassan’s that one should stick with the standard liturgy and not change it to conform with Biblical Hebrew. R. Espinoza, originally from Tunisia was unsuccessful in publishing his rebuttal and it remained in manuscript, although its existence was known to many. R. Espinoza pulls no punches and takes R. Bassan to task in very sharp terms for his advocating these changes. As mentioned above this was to no avail as either surreptitiously or knowingly many of the changes and other similar ones have in fact become standard today.

Recently both the Yashresh Ya’akov and R. Espinoza’s work Yesod HaKium have been republished together. This edition which includes an extensive introduction which contains all the history above and more is excellent. Obviously, for understanding the development of the liturgy of the prayer book this is extremely important. Also those interested in bibliographical quirks will also enjoy these books. The book is available from Beigeleisen books (718-436-1165) who has informed me he has recently received a new shipment of these as the prior one had been sold out. This new edition was edited by Rabbis Moshe Didi and David Satbon from Kiryat Sefer, Israel (ת.ד 525 and 154 respectively).

For more on these books see here.

Sources:

[1] This understanding that R. Ya’akov Basson is the actual author runs counter to many earlier assertions that the author was R. Avrohom Basson. In the new edition of this work, however, they demonstrate the problems with associating R. Avrohom and instead argue that in fact it is R. Ya’akov.

[2] Satnow was not the only one; according to some, R. Saul Berlin, in the Besamim Rosh, offered similar hints to his authorship of this controversial work.