Approbations and Restrictions:

Printing the Talmud in Eighteenth Century Amsterdam and Two Frankfurts

by Marvin J. Heller

Approbations designed to protect the investment of printers and their sponsors when publishing a large work such as the Talmud were well intentioned. Unfortunately, the results were counter-productive, resulting in acrimonious disputes between publishers within and between cities. This article discusses the first approbations, issued for the Frankfurt on the Oder Talmud (1697-99), and the resulting dispute with printers in Amsterdam in 1714-17. The background of the presses and the pressmarks utilized by the printers are discussed, giving a fuller picture of the printing of the Talmud in the subject period, as well as addressing antecedent (Benveniste) and subsequent editions.

Approbations for books have multiple purposes, among them commendations, indicating approval or praise for the subject work, confirming that a book’s contents do not contain forbidden or prohibited matter, and to protect a publisher’s investment from competitive editions for a fixed period of time. This article is concerned with the last purpose, here rabbinic approbations (hascoma, pl. hascomot) limiting or preventing rival editions of the Talmud published in the last decade of the seventeenth century into the first half of the eighteenth century.

The restrictive approbations discussed here are unlike those issued previously, such as the first approbations for a Hebrew book, R. Jacob Barukh ben Judah Landau’s (15th cent.) concise halakhic compendium, Sefer Ha-Agur (Naples, 1487), one of seven approbations, that of R. Judah ben Jehiel Rofe (Messer Leone, 15th cent.) stating he has examined ha-Agur, and, “it is a work that gives forth pleasant words. . . . I have, therefore, set my signature unto these nectars of the honeycomb, these words of beauty,” or those in Italy or in Basle, which assured the authorities that nothing untoward or offensive to Christianity was included in the book, or to current approbations, which assure the reader that a work’s contents are in conformity with the community’s religious standards. In contrast, the approbation issued for the Frankfurt on the Oder Berman Talmud, and to subsequent editions, was a license for a fixed number of years, prohibiting other publishers from printing competitive editions that would prevent the printer and his sponsor(s), who would otherwise be reluctant to make the substantial investment required to print such a large multi-volume work as the Talmud, from realizing a return on their investment.

The discord arising from restrictive approbations for printing the Talmud were not the first such disputes. In Amsterdam, disputes between printers arose over editions of the Bible. Johannes Georgius Nisselius and Joseph Athias competed in the mid-seventeenth century over a Sacra Biblia (Hebrew Bible) for the use of students and several years later Athias and Uri Phoebus were involved in controversy over their translations of the Bible into Yiddish, competing for the Jewish market in Poland. Arguing over the right to publish for and sell to that market, they sought to reinforce their positions by seeking approbations from the Polish, as well as the Amsterdam rabbinate.[1] Nevertheless, their competition pales in contrast to the recurring altercations over the right to print the Talmud, which spanned several centuries and much of the European continent.

Raphael Natan Nuta Rabbinovicz writes that the intent in granting this and subsequent approbations was for the good of the community, to insure investors a reasonable return on their investment. The result, however, was that the Talmud was printed only eight times in the century from 1697 to 1797, and the price of a set of the Talmud was dear. Prior to that the Talmud had been printed several times in Italy and Poland within a relatively short period of time, the primary impediment then being the opposition of the Church and local authorities. Rabbinovicz concludes that after 1797 the use of restrictive approbations declined, with the consequence that within four decades, to 1835, the Talmud was printed nine times.[2]

During last decade of the seventeenth century into the first half of the eighteenth century several rival editions of the Talmud appeared, beginning with the Frankfurt on the Oder Talmud (1697-99) followed by two incomplete editions in Amsterdam (1714-17 and 1714), the Frankfurt on the Main Talmud (1720–22), again in Amsterdam (1752–1765), and finally the Sulzbach Red (1755-63) and Black (1766-70). We are concerned with and focus on the early editions, that is, on the dispute between the Frankfurt on the Oder and Amsterdam printers, their dispute resulting from restrictive approbations issued to presses printing the Talmud. This article discusses the background of the Hebrew presses that published these Talmud editions in the seventeenth and eighteenth century; its primary focus, being the disputes resulting from the restrictive approbations.

I Amsterdam – Benveniste Talmud

Amsterdam has a distinguished place in Jewish history. Among the notable features of that city’s Jewish community are its printing-houses, among the foremost in Europe for centuries. Highly regarded, Amsterdam imprints were distributed and sold throughout all of Europe. The preeminence of Amsterdam as a European book center is evident, for it is estimated that the output of the Dutch presses in the seventeenth century exceeded the combined production of all the presses of all other European countries. The number of book-printers totaled 273 at its peak in 1675-99, employing at its height in excess of 30,000 people supported through some facet of the book trade.[3] The important works published by its presses include editions of the Talmud, beginning with the Benveniste Talmud of 1644-47, through the much praised Proops’ Talmud of 1752-65. In addition to complete editions of the Talmud individual treatises, frequently in a smaller format, were also published for students and individuals who did not require or who could not afford a complete Talmud.[4]

The printing of Hebrew books in Amsterdam by Jews begins in 1627, when two printers published books, Manasseh (Menasseh) Ben Israel (1604-57) and Daniel de Fonesca. The former’s press was the first to publish with a Sephardic rite prayer-book, completed on January 1, 1627. Manasseh Ben Israel would achieve acclaim that, together with its founder’s many other achievements, is still recalled today. Manasseh did not publish Talmudic tractates but his press did issue three critical editions of Mishnayot (1632, 1643, and 1646). He also intended to publish an edition of the Talmud but that did not come to pass.

The next printer of Hebrew books of import in Amsterdam was Immanuel (Imanoel) Benveniste. Benveniste is believed to have been among the Jewish refugees from Spain or Portugal, and that he was descended from the illustrious Sephardic family of that name.[5] Beneveniste relocated to Amsterdam because, by the mid-seventeenth century that city offered better opportunities for the distribution of Hebrew books than any city in Italy.[6] Beneveniste was the publisher of the first Amsterdam Talmud, printed from 1644-47. The Benveniste Talmud is in a smaller (c. 260:195 cm.) quarto format than the usual large folio editions.[7]

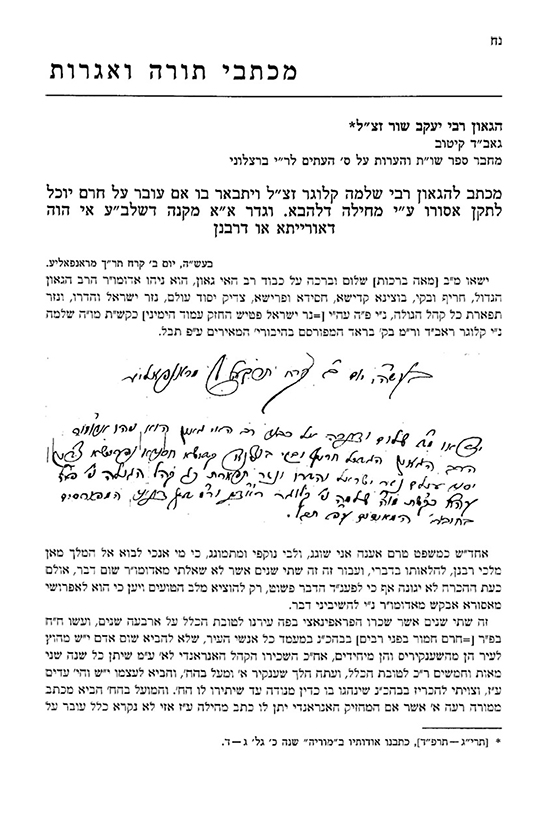

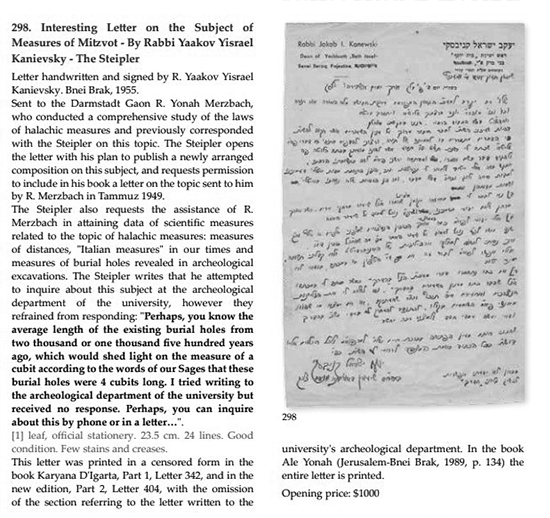

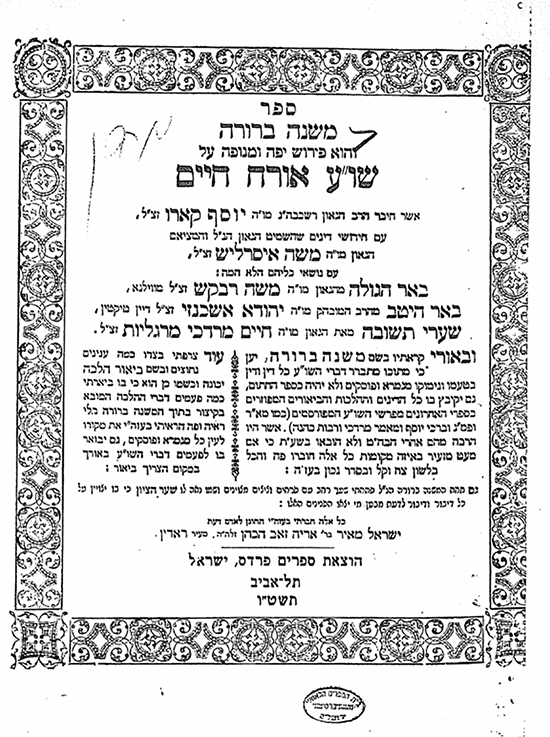

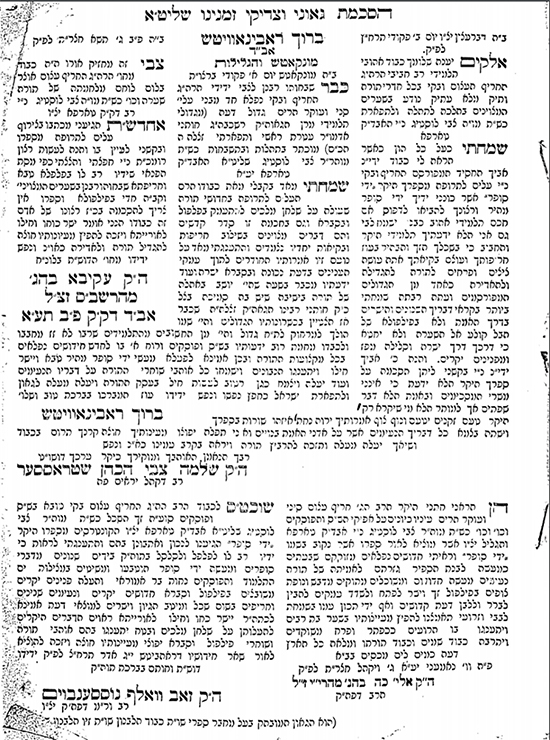

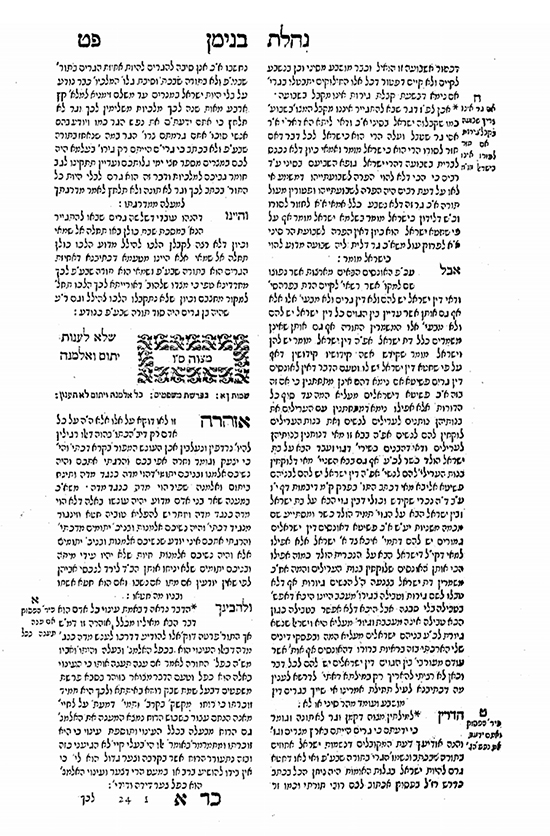

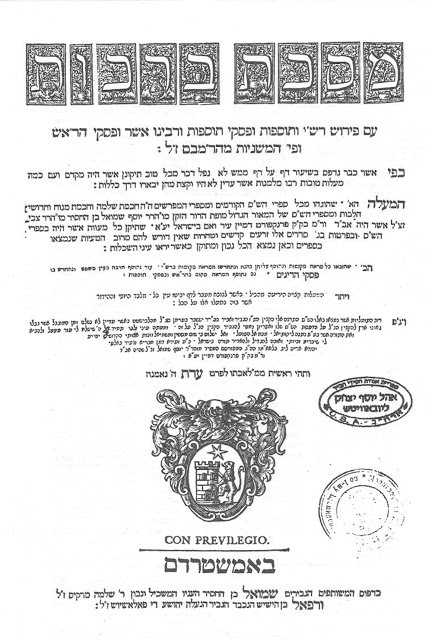

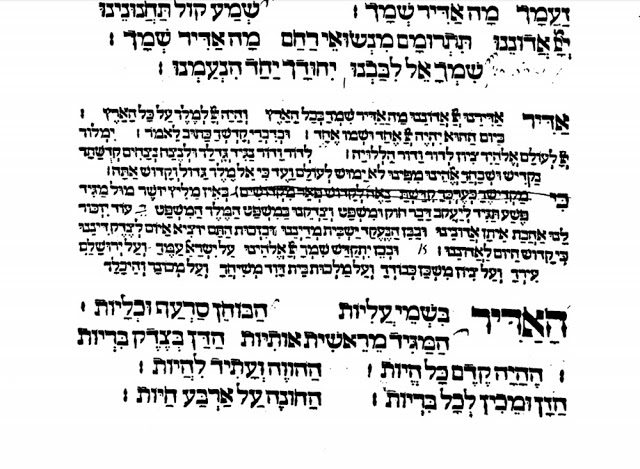

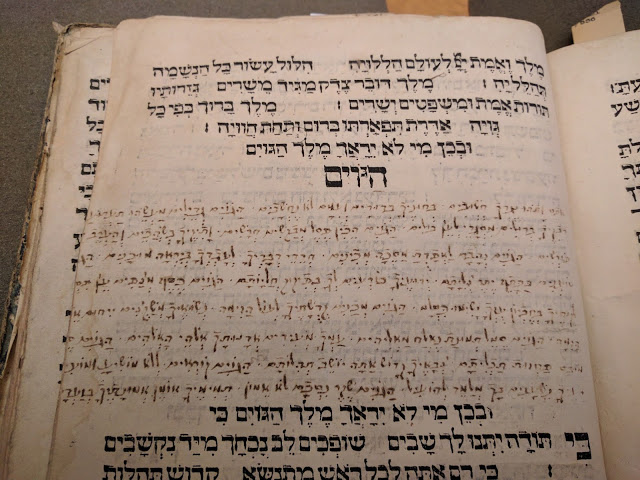

Fig. 1

Although not subject to restrictive approbations it is included here due to its relevance to the history of the printing the Talmud in Amsterdam and because the title-pages of Benveniste’s publications are distinguished by his escutcheon, an upright lion facing inward towards a tower; a star is above the lion and the tower. The lion is on the viewer’s right, the tower on the left. At least six forms of Benveniste’s device have been identified. In all cases, excepting his Talmudic treatises, Benveniste’s insignia is set in a crest above an architectural frame surrounding the text of the title page. On the title-pages of the Benveniste tractates his mark appears at the bottom of the page in an ornamental shield, with a helmet in the crest (fig. 1). Given the high regard of most Benveniste imprints this device was subsequently used by several printers in Amsterdam, including two of the following subject editions, as well as by other presses in various locations.[8]

This Talmud has been has been praised for restoring expurgated material. Unlike Benveniste’s other publications, however, the Beneveniste Talmud is not highly regarded. Raphael Natan Nuta Rabbinovicz quotes from an approbation given by R. Moses Judah ha-Cohen, Av Bet Din, of the Ashkenazi community in Amsterdam, for the Berman Talmud (Frankfurt on the Oder, 1697-99) which states that Benveniste, due to his concern over expenses, printed a Talmud edition which was, due to its small size, difficult to learn from. Furthermore, Benveniste used letters that were “the smallest of the small and blurred so that the users eyes become heavy and his sight wanders as if from old age.”[9] This notwithstanding, no less a personage than the Vilna Gaon (R. Elijah ben Soloman Zalman, Gr”a, 1720-70) made use of the Benveniste Talmud, Rabbinovicz writing that “he had heard from a great Talmudic scholar who related that he had seen a Talmud from which the Gr”a had learned by R. Judah Bachrach (1775-1846) av bet din Seiny with his (Gr”a’s) handwritten annotations, brief and varied from his printed annotations, and that it was a Benveniste Talmud.”[10]

II – Frankfurt on the Oder – Michael Gottschalk

Printing with Hebrew letters in Frankfurt on the Oder begins when the Christian printers Joachim and Friedreich Hartmann (1594-1631), who, using new Hebrew fonts and vowels cast by Zechariah Crato (?) of Wittenberg, published a Hebrew Bible in 1595-96. While there are references to an even earlier Bible, half a century earlier, that is uncertain. More than a century later, Johann Christoph Beckmann (1641-1711), professor of Greek language history, and theology at the University of Frankfurt on the Oder, operated a printing-press in Frankfurt on the Oder from 1673 to 1717, which he acquired from his brother Friedreich on June 1, 1673 for 400 Thaler; Friedreich, in turn, had purchased the press for a like amount. Beckmann obtained a travel scholarship from the Brandenburg Elector and, during his travels in Europe came to Amsterdam. In 1663, in that city, Beckmann met Jewish students, the renowned R. Jacob Abendana (1630-85), and studied Talmud. In 1666, Beckmann returned to Frankfurt, where he obtained a position at the university (Viadrina), teaching there until his death in 1717 and serving as rector eight times. Because of the admission of Jewish students, the Viadrina became the “Amsterdam of the East,” both Hebrew and oriental studies being of importance.[11]

Beckmann was granted, initially, on May 1, 1675, a license to employ two Jewish workers, under the direct protection of the university, to print a Hebrew Bible, this despite of the protests of Frankfurt city. By 1693, however, Beckmann found that his responsibilities at the university left him with insufficient time to manage the press. Therefore, he contracted with Michael Gottschalk, a local bookbinder and book-dealer to manage the printing-house, transferring all of the typographical equipment and material to Gottschalk. Their arrangement was noted on the title-pages of the books issued by the press, which stated “with the letters of Lord Johann Christoph Beckmann, Doctor and Professor . . . at the press of Michael Gottschalk.” Gottschalk became the moving spirit of the press for almost four decades.

After printing several varied Hebrew titles Gottschalk approached Beckmann, requesting that he obtain permission to reprint the Talmud. Beckmann petitioned Friedreich III, Elector of Brandenburg (1657-1713, reigned 1688-1713, from 1701 King of Prussia), requesting a license to print the Talmud. Friedreich, in turn, sought the counsel of the Berlin professor Dr. Daniel Ernest Jablonski (1660-1741), from 1691, court preacher at Königsberg for the elector of Brandenburg, Friederick III. Jablonski, a Christian German theologian of Czech origin, an orientalist, had been associated with universities in Holland and England, settling in Lissa in 1686, and from there moving to Berlin. In 1700, Jablonski became a member of the Academy of Sciences in Berlin. Jablonski established a Hebrew press in Berlin, publishing a scholarly edition of the Hebrew Bible based on the Leusden edition (Amsterdam, 1667, Atthias) and a translation of Richard Bentley’s A Confutation of Atheism into Latin (Berlin, 1696). Jablonski, was to become personally involved with Hebrew printing in Berlin, and would be participate in the publishing of two later editions of the Talmud.

When a sponsor was sought for the Frankfurt on the Oder Talmud, Beckmann found one in the Court Jew Issachar (Ber Segal) ha-Levi Bermann (1661-1730) of Halberstadt, known as Bermann Halberstadt or, in his commercial dealings with the non-Jewish world, as Behrend Lehmann. It was Bermann who bore the cost of this Talmud, and whose name is associated with it. Selma Stern observes that Bermann was a pious and observant Jew throughout his life. He was held in high regard by his fellow Jews; and was described as “a second Joseph of Egypt” and “the chosen of the Lord, who warns him about the machinations of his enemies and miraculously rescues him when he is in dire straits.” Bermann was known among his people as “the founder of the Klaus in Halberstadt, the publisher of the Talmud, the man who defeated the first Prussian king at chess and who even in the glittering world of the Court never forgot Eternal Truth, corresponded to the ideal which Jews have had of their great men leaders.”[12]

Beckmann and Bermann entered into an agreement to publish the Talmud, Beckmann transferring his rights to Bermann, and the latter accepting responsibility for publishing the entire edition, making an initial payment of three hundred reichsthalers at the time of the agreement.[13] The printer was to be the Christian, Michael Gottschalk. Approximately half of the sets of this Talmud, known as the Berman Talmud, were distributed by Bermann to yeshivot and penurious scholars who could not otherwise have acquired a complete Talmud. Not only did he spend fifty thousand reichthalers of his own money to publish the Talmud, from which he apparently saw no financial gain, distributing copies to Talmudic students, but afterwards granted permission to the Amsterdam and Frankfurt on the Main printers to publish a complete Talmud, this in spite of the fact that he had approbations preventing republication of competitive editions.[14]

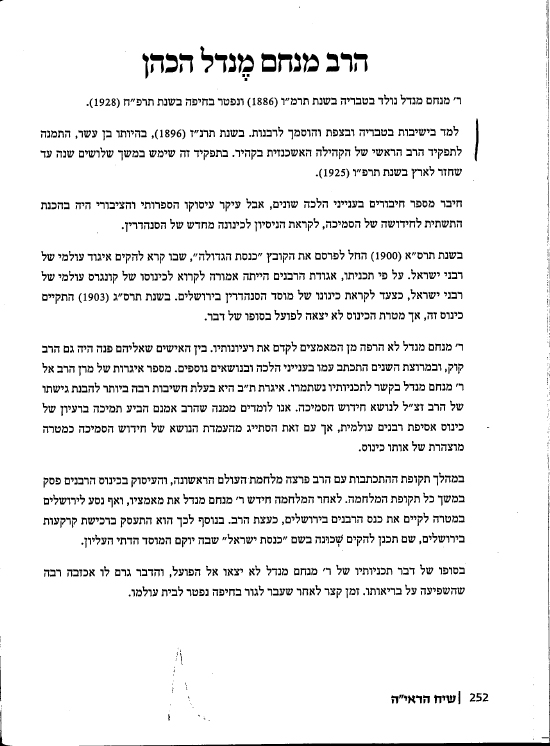

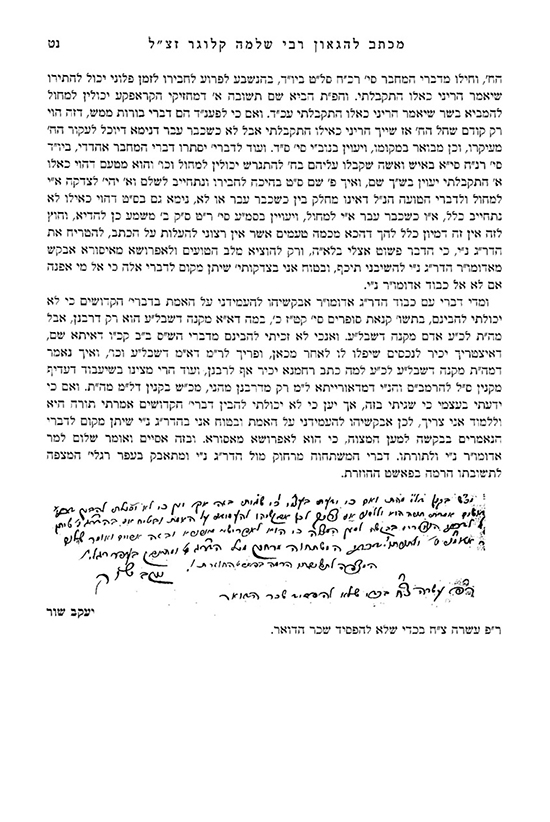

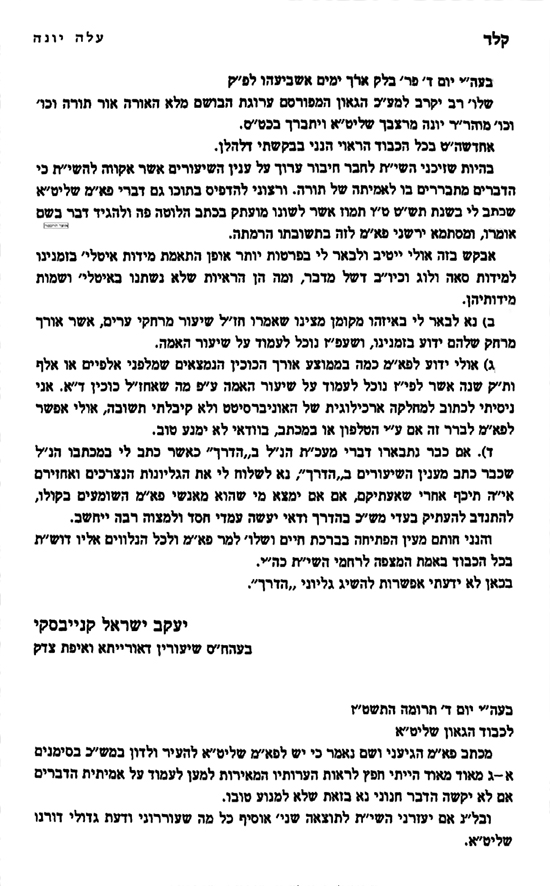

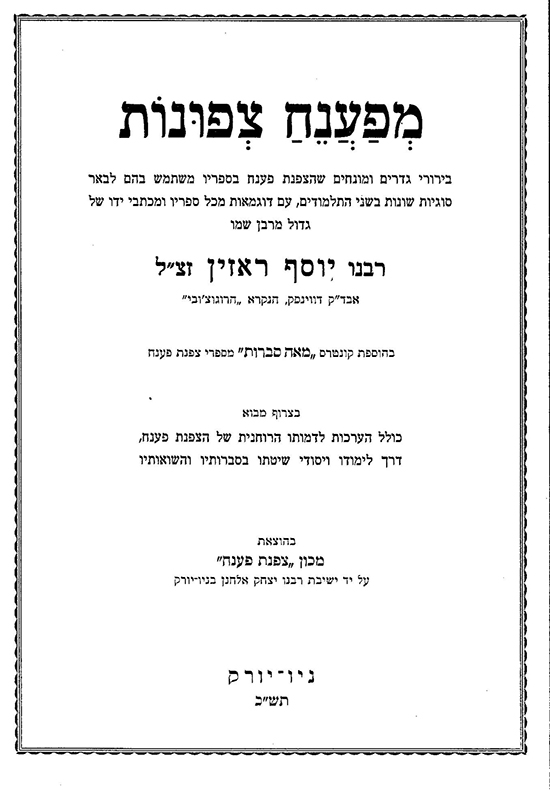

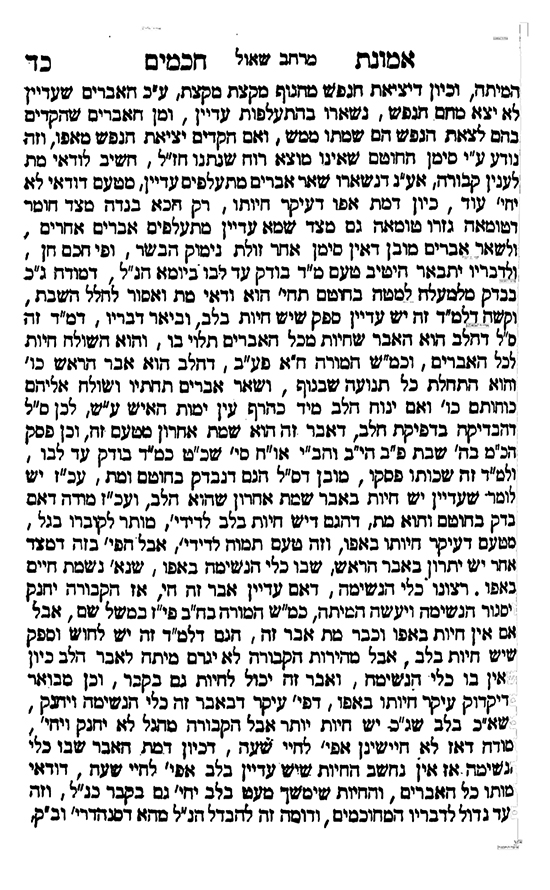

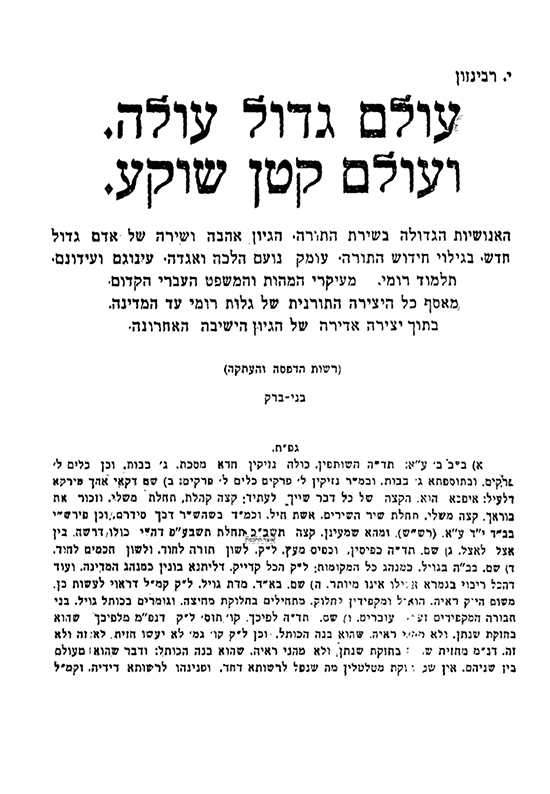

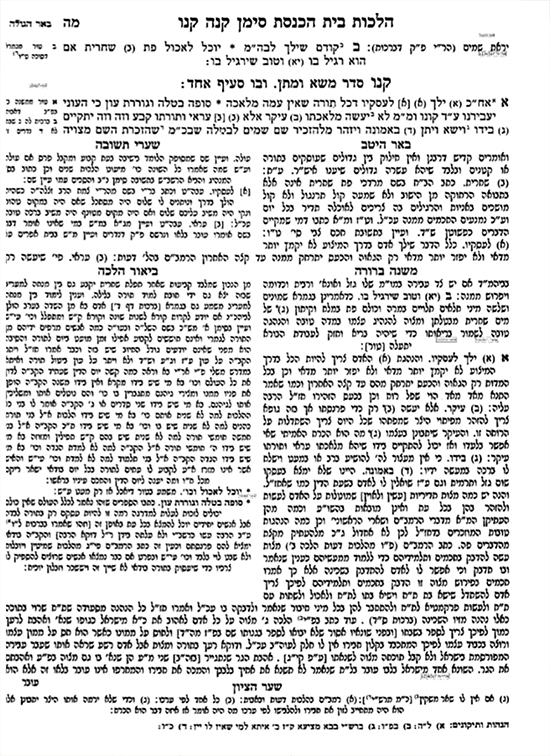

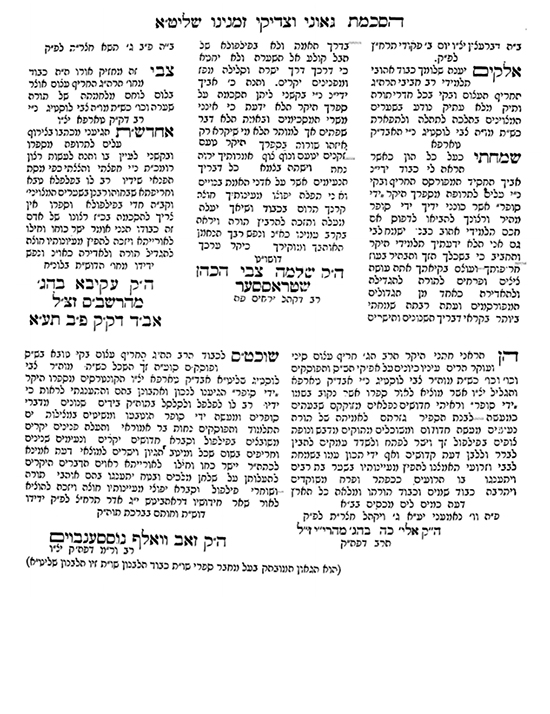

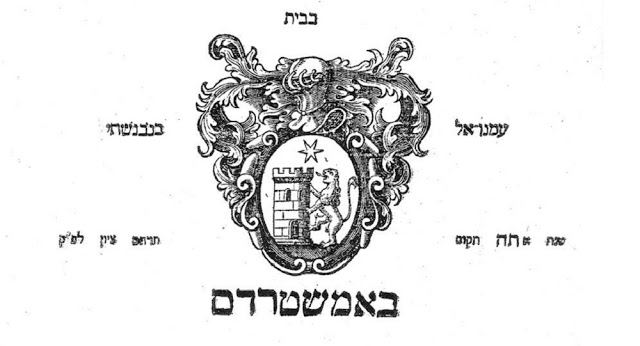

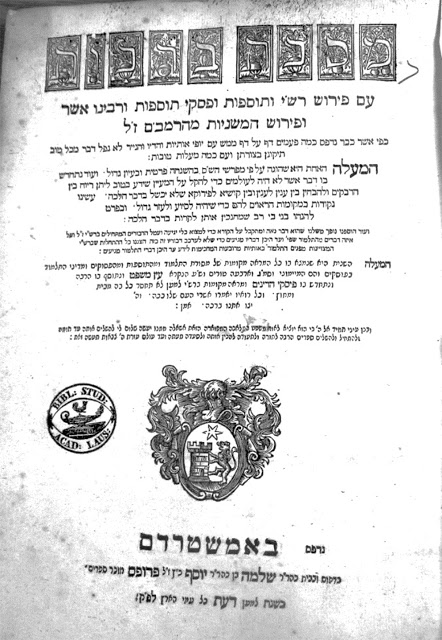

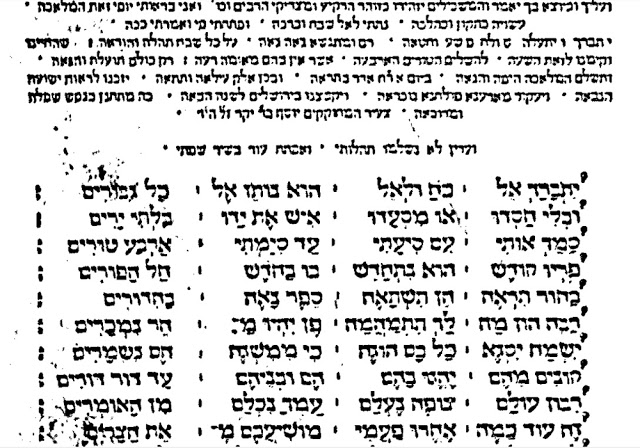

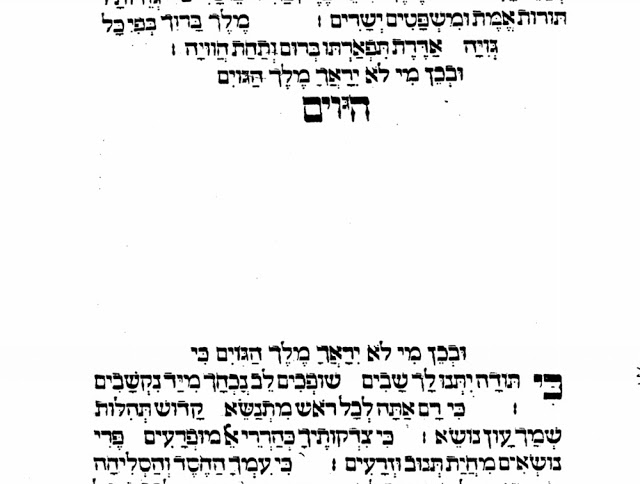

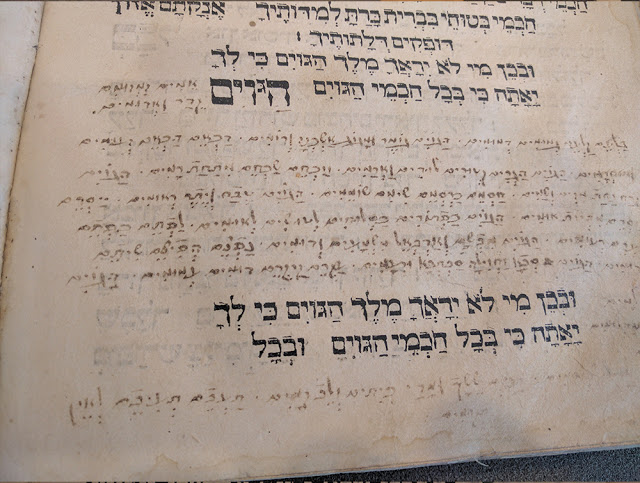

Fig. 2

Each volume of this Talmud has two title-pages. The first, a volume header page, has an engraved copper plate title-page (fig. 2) by the craftsman Martin Bernigeroth (1670-1733), Dt. Kupferstecher u. Zeichner (engraver and illustrator).[15] This initial title-page consists of an upright lamb with a pitcher on top of a portico. Below it, on the sides of the page, are Moses to the right and Aaron to the left. Beneath them, similarly situated, are King David with a harp, and King Solomon. Above each figure is that individuals’ name. Avraham Habermann and Avraham Yaari both write that the sheep and laver represent Bermann, who was a Levi. Yaari adds that the sheep further represents Bermann’s “mazel” or constellation, for Bermann was born on the 24th of Nissan (April 23), 1661, the astrological symbol for that month being a sheep.[16]

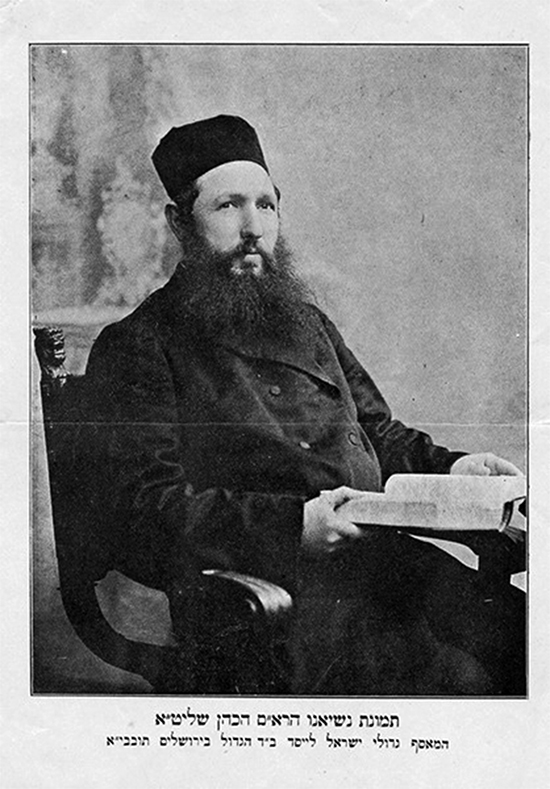

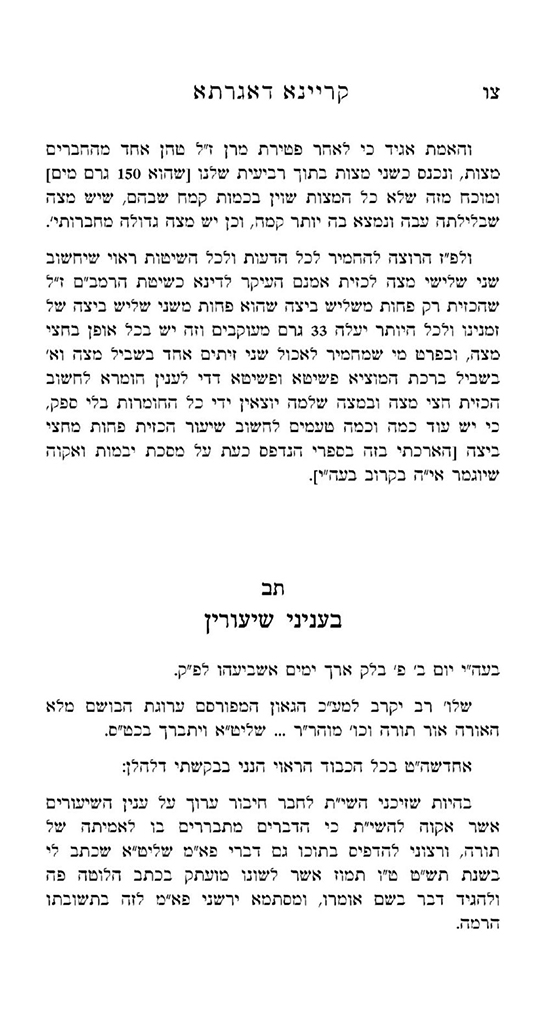

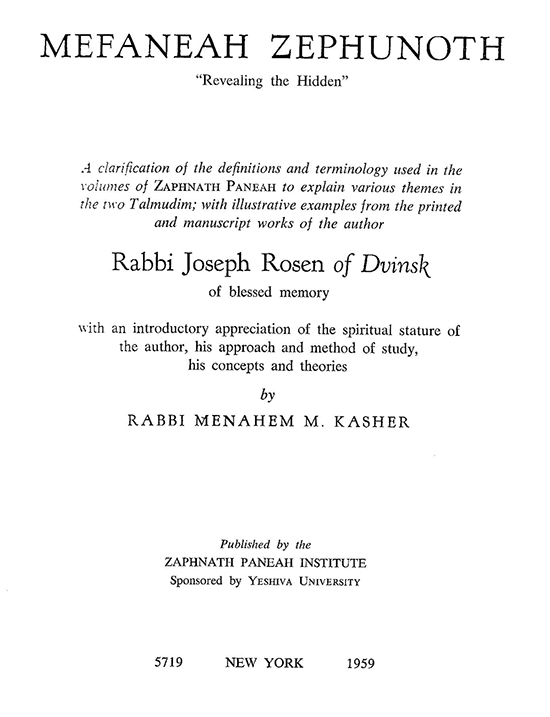

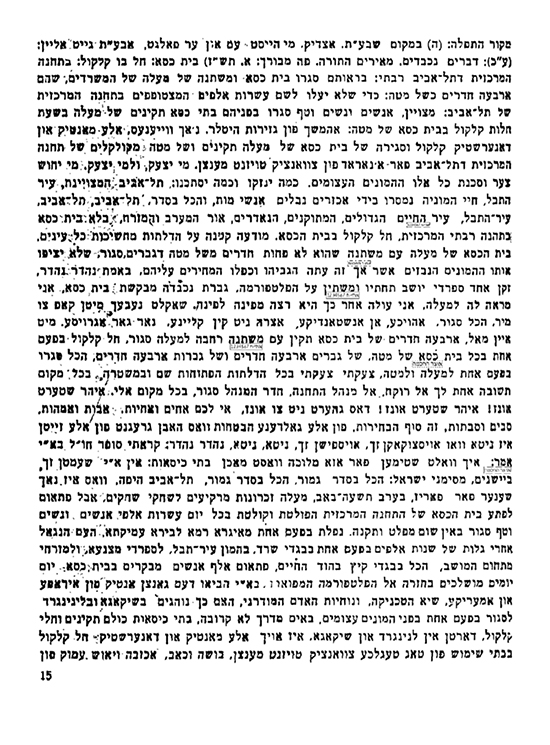

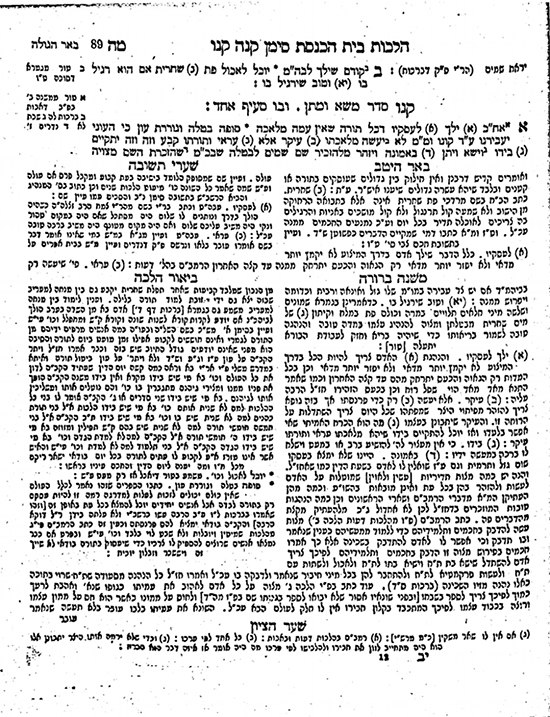

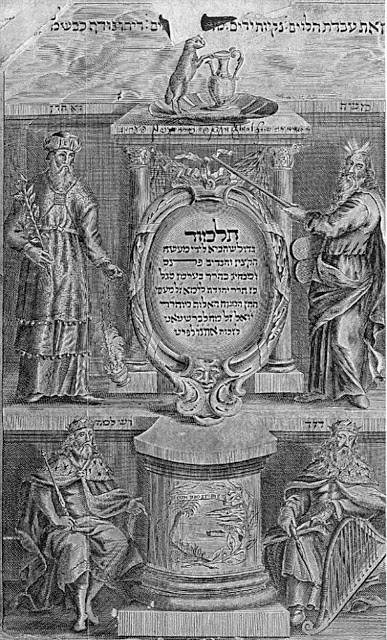

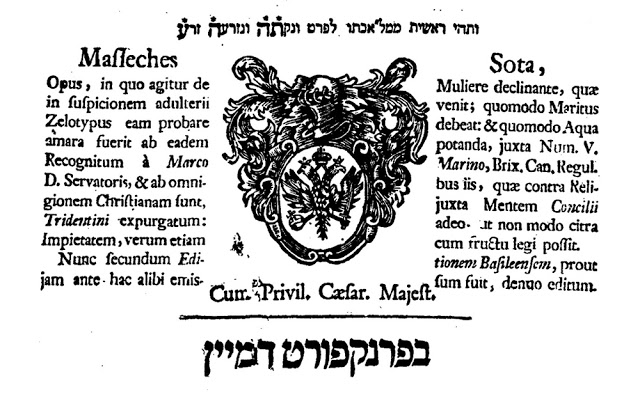

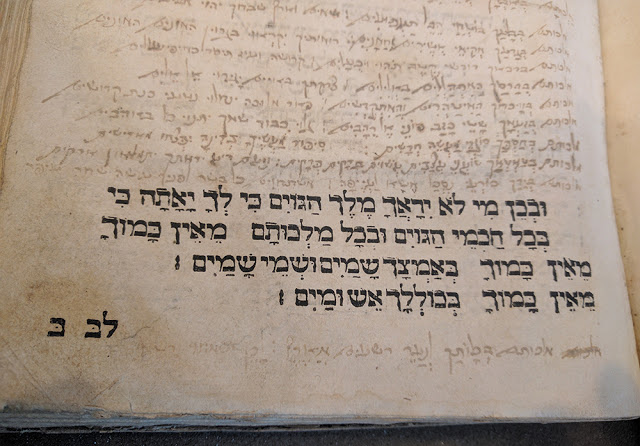

The second textual tractate title-page follows immediately after the volume title-page. The tractate title-pages are basically copied, with several modifications, from the Benveniste Talmud; but also includes some features characteristic of the Basel Talmud, which is supposed to be the source of this edition. The text concludes in Latin, informing that it is “in accordance with expurgations of the Council of Trent. . . .” and that it was printed in conformity with the Basle edition (1578 – 1581). Between the Hebrew and Latin text is Michael Gottschalk’s printer’s mark (fig. 3), which appears on the title-pages of this Talmud. It is a mirror-image monogram (cipher) of his name, the first usage of such a monogram in a Hebrew book.[17]

Fig. 3

Printed with this Talmud are approbations for the edition. When Johann Christoph Beckmann secured permission in 1695 from the Kaiser, Leopold, and from Friedreich Augustus, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, to print the Talmud, he was given not only authorization to print the Talmud, but was also granted the sole and exclusive right to do so for twelve years. Leading rabbinic figures, according to Rabbinovicz, issued restrictive approbations, the first instance in which such rabbinic licenses were granted. The rabbis who signed the approbations were R. Naftali ben Isaac ha-Kohen Katz, av bet din (head of the rabbinical court) of Pozna, R. Joseph Samuel of Cracow, av bet din of Frankfurt on the Main, R. David ben Abraham Oppenheim, av bet din of Nikolsburg, and R. Moses Judah ha Kohen and R. Jacob Sasportas of Amsterdam concurred in granting this monopoly, issuing approbations (hascomas) for twenty years.

These approbations were unlike those issued previously in Italy, which assured the authorities that nothing untoward or offensive to them was included in the book, or current approbations, which assure the reader that a work’s contents are in conformity with the community’s religious standards. The approbation issued for this Talmud, and to subsequent editions, was a license for a fixed number of years, prohibiting other publishers from printing competitive editions that would prevent the printer and his sponsor(s), who would otherwise be reluctant to make the substantial investment required to print the Talmud, from realizing a return on their investment.

Oppenheim refers to the burning of the Talmud and other Hebrew books in the Chnielnicki massacres tah ve-tat (1648–49), fires that resulted in the loss of many Hebrew books, resulting in a dire need for Talmudic tractates. Indeed, he writes that the entire Jewish educational system was endangered due to insufficient copies of the Talmud. He praises Lehmann, noting his benevolence in distributing half of the copies to needy students free of charge.[18] Towards the end of his long and flowery approbation Oppenheim forbids the printing of the Talmud by anyone without the permission of Issachar Bermann SG”L, from the day that printing commences until twenty years have elapsed from its completion. This prohibition is “whether for all or for part, even for one tractate only, whether for oneself or for others, and is not to be done by means of guile or ruse.” To enforce his decree R. Oppenheim states that “this decree falls equally upon the purchaser as well as the seller, for that which a rabbinic court declares ownerless is ownerless. Any [such tractate] found in a person’s possession without license, is to be taken forcibly, without payment or deed . . .”[20]

Similarly, R. Joseph Samuel of Cracow begins by praising Berman, noting that all realize that these many days many thought to print the Talmud due to its being unavailable, not to be found, except one to a city and two to a family. He notes, however, that although many wanted to print the Talmud it was to no avail, for it is a large project of much work and difficult to complete, until the Lord aroused the spirit of R. Berman of Halberstadt for the public benefit and the honor of the Torah, to print an entire Talmud on good paper, with fine ink, and diligent workers, well edited. Lest there be many who “bear gall and wormwood” (Deuteronomy 29:17) who also wish to print the Talmud and therefore cause great harm R. Berman’s interests, and “lock the door before him” (cf. Bekhorot 10b) who performs a great mitzvah to benefit the public, for “such is such theTorah, and such is its reward” (Berakhot 21b, Menahot 21b)? He therefore, concurs with the other leading rabbis to decree,

Excommunication and a ban on each and every person who should take it upon himself to print the Talmud in its entirety or in whole or in part without the agreement and knowledge of the noble R. Berman, except for a section needed to learn in yehivot, which is not included in the ban. It is permitted to print only that section and not a complete tractate in order to “magnify the Torah, and make it glorious” (Isaiah 42:21). A blessing should come upon he who hearkens to our words, may blessings of good come upon him and may he receive good from God Who is good. But “he who breaches through a fence, shall be bitten by a serpent” (Avodah Zara 27b) . . . and all the curses written in the Torah shall come upon him. . . .

Even before the privilege for this Talmud had expired the need for a new edition became apparent, numerous appeals being made to Issachar Bermann to republish the Talmud. Gottschalk, who had the rights granted to Beckmann, was also favorable to reprinting the Talmud. The Talmud had sold well and Gottschalk, as a result, had become a wealthy man.[20] Frederick William I of Prussia acceded to their request on May 23, and a new privilege, dated October 13, 1710, was granted to Gottschalk by Joseph I, successor to Leopold, in 1705, to print the Talmud and sell it throughout his domain, albeit with the customary restrictions and with the provision, as with all Hebrew books, that five copies be brought to the Imperial court. Similarly, on January 11, 1711, Frederick Augustus I (Augustus II), Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, also granted such a privilege. Nevertheless, these privileges were not immediately acted upon by Gottschalk and it would be several years before he printed the second of his three editions of the Talmud.[21]

III – Marches and de Palasios and Solomon Proops

Individual tractates were frequently published in Amsterdam, to address the continuing communal need for treatises for study purposes. The printers of these tractates include Moses Mendes Coutinho, Asher Anshel and Issachar Ber, Issac de Cordova, Joseph Dayyan and Moses Frankfurter, the latter two dayyanim (judges) of the Ashkenaz religious court. During the interval between the Benveniste and the Frankfurt on the Oder editions of the Talmud no complete Talmud had been printed. It must have appeared unseemly, however, that in Amsterdam, the center of Hebrew printing, with the greatest number of, and the largest, Hebrew printing-presses, that no Talmud edition had been issued for over six decades.

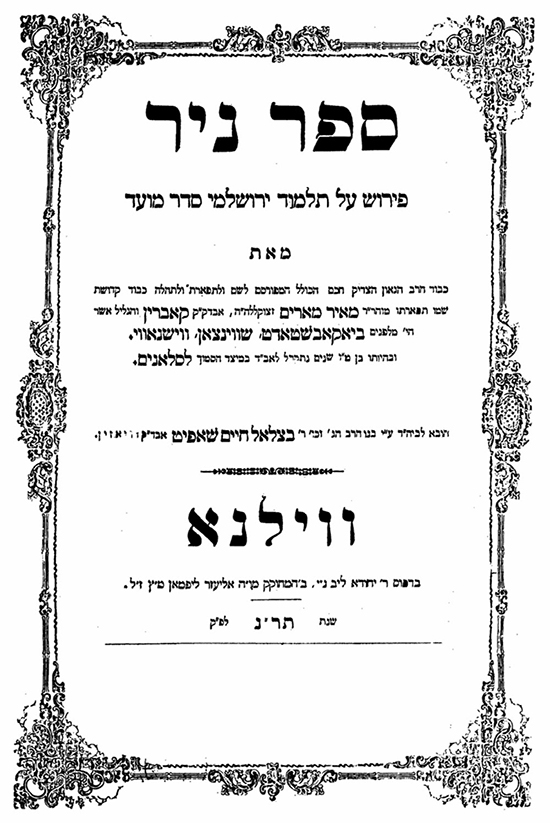

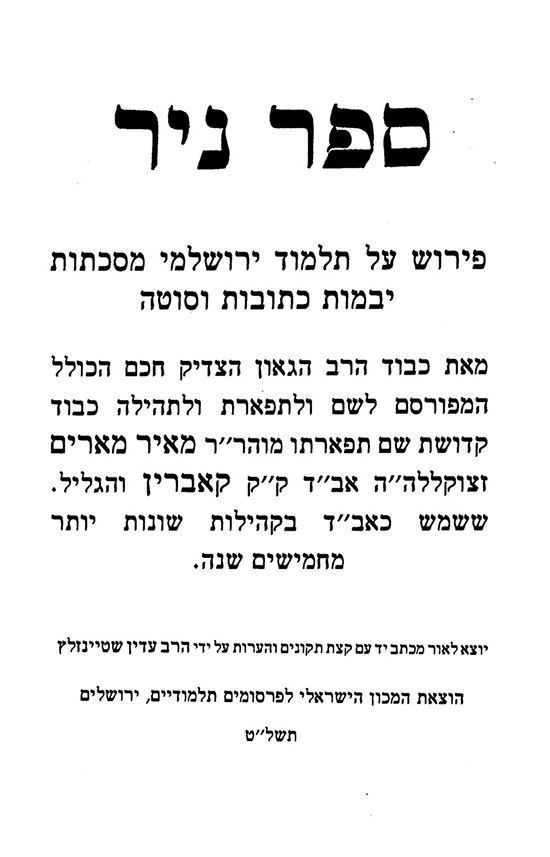

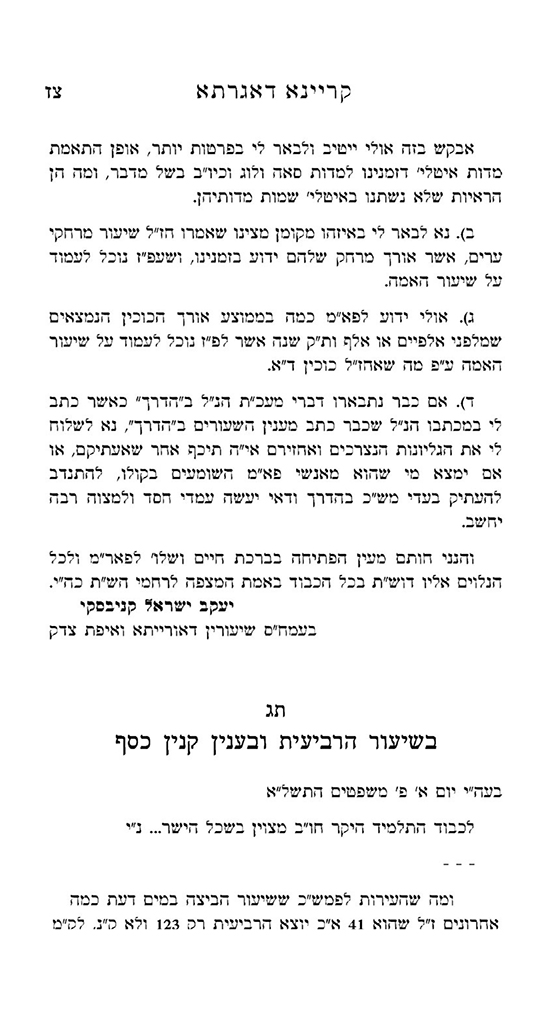

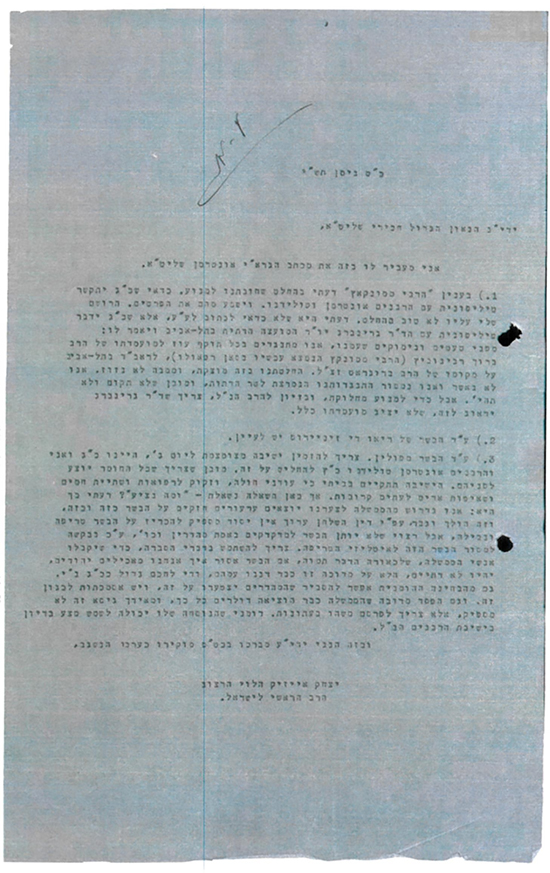

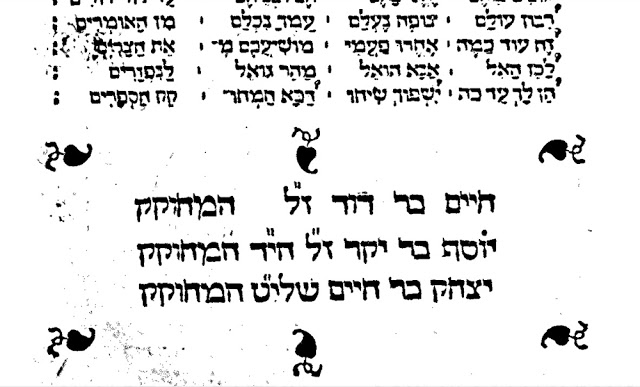

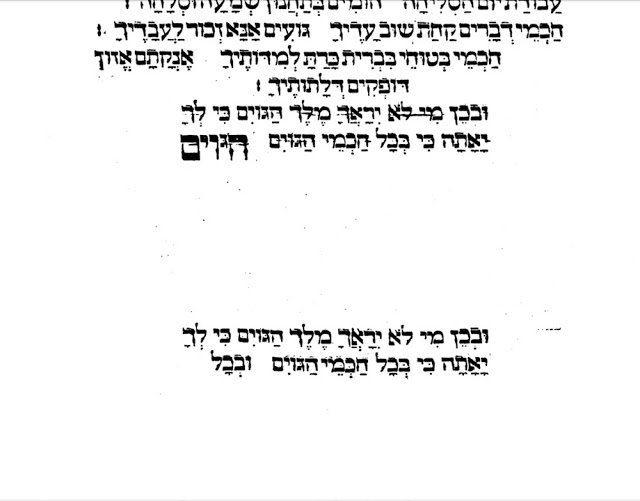

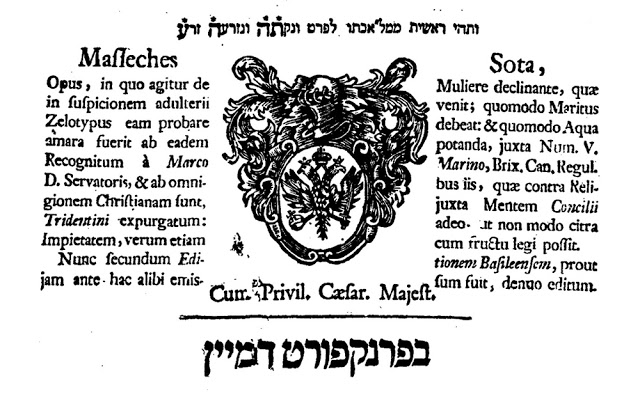

An attempt to correct this, even if that was not the printers’ primary intent, occurred during the interval between the first and second Frankfurt on the Oder editions of the Talmud. two independent editions of the Talmud were begun in Amsterdam in 1714. The first was published by the partners Samuel ben Solomon Marcheses and Raphael ben Joshua de Palasios, the second by Solomon Proops. Both publishers began to print in 1714; both editions are in attractive large folio format; the title-pages of both Talmuds have, as a printer’s device, copies of the Benveniste escutcheon (figs. 4, 5). Most importantly, neither Talmud edition was completed.

Except for a Sephardic rite prayer-book, printed by Samuel Marcheses at the press of Joseph Athias, neither partner, prominent members of the Amsterdam Sephardic community, had previously published any works. Their motivation in establishing a press was for the specific purpose of printing the Talmud. Furthermore, they intended to do so in such a manner as to produce an especially fine and accurate edition. The workers would not be hurried, so that they could work with care, reducing errors, supervised by R. Moses Frankfurter, who would help establish the correct text.[22] Marcheses and de Palasios did so under the influence of R. Judah Aryeh Loeb ben Joseph Samuel Schotten ha-Kohen (1644-1719), av bet din of Frankfurt on the Main, and his father-in-law R. Samuel Settin of Frankfurt n Main. Judah Aryeh Loeb had previously attempted to have a Talmud printed in Frankfurt in 1710 but, due to the prior approbations granted to the Frankfurt on the Oder Talmud his efforts were to no avail, and he was unable to get authorization from the emperor to print the Talmud. In 1713, Judah Aryeh Loeb explored the possibility of obtaining permission to print in Frankfurt from the Kaiser in Vienna, but did not even receive a response to his inquiries. Judah Aryeh Loeb next turned to Amsterdam where, with the assistance of his father-in-law and the agreement of R. Issachar (Ber Segal) ha-Levi Bermann who had the prior approbation he commenced to print the Talmud.[23] Subsequently Samuel Settin arranged for Samuel Marches and Joshua de Palasios to undertake this venture, arranging for R. Zvi Hirsh of Sharbishin, at the time a resident of Amsterdam, to visit various Jewish communities, seeking subscribers to defray the cost of publication.[24]

Printing began with tractate Berakhot in 1714; the following tractates are recorded by Rabbinovicz as having been printed: 1715 – Shabbat and Seder Zera’im: 1716 – Eruvin, Pesahim, Hagigah, Mo’ed Katan, Yoma, Shekalim, Megillah, and Ketubbot: 1717 – Bezah, Rosh Ha-Shanah, Sukkah, Ta’anit, and Yevamot.[25] Printing was discontinued in 1717 due to the approbations issued to the Frankfurt on the Oder printer for the Berman Talmud.

The approbations for this edition appear in tractate Shabbat. They are from R. Solomon ben Jacob Ayllon, R. Gabriel ben Judah Loeb of Cracow, R. Samuel ben Joseph Schotten ha-Kohen, R. Baruch ben Moses Meir Rappaport, R. Ezekiel ben Abraham of the house of Katzenellenbogen, R. Menahem Mendel Ashkenazi, R. Isaac Aaron ben Joseph Israel of Metz, and R. Phineas ben Simeon Wolff Auerbach of Cracow. The approbation of R. Menahem Mendel Ashkenazi, at the time Landesrabbiner in Bamberg and Baiersdorf, subjected anyone who violated the copyright to excommunication, placing a

ban, and anathema, and death on anyone who would reprint the Talmud during twenty years from the completion of this edition without the knowledge or permission of the above [Judah Aryeh Loeb] in any manner, whether in its entirety or in part, even a single tractate, excepting a section needed for learning in the yeshivot according to the requirements of the times, whether by himself or by his agent or his agent’s agent, directly or indirectly, whether a member of his household or not a member of his household . . . and he who heeds our words shall be blessed . . .

Marcheses and de Palasios acknowledge the existence of the prior restrictive approbation for the Berman Talmud on the title-pages of their tractates, which note that most of its benefits can be attributed to the Talmud of R. Issachar Bermann of Halberstadt, and also state

[And even though] most of the qualities to be found in this Talmud were acceded to me by the noble, the eminent, the distinguished R. Issachar Bermann Segal of Halberstadt even though the time restricting publication established by the geonim of the land for the above noble (Berman) for printing his Talmud has not yet elapsed. An palanquin to the above eminent noble for this. Now “My eyes and my heart are always toward the Lord” (cf. Psalms 25:15) . . .

Fig. 4. 1714, Berakhot, Marches and de Palasios

Fig. 5. 1714, Berakhot, Solomon Proops

In the same year, 1714, that Berakhot was published a second Talmud was begun in Amsterdam. The publisher of that edition was Solomon ben Joseph Proops, then a book dealer, Maecenas to numerous Amsterdam publishers, and the founder of the famous Proops press. He had been a book-dealer and financed and partnered in a number of works published at other presses before establishing his own press in 1704. The printing-house founded by Solomon Proops would become one of the most illustrious in the history of Amsterdam Hebrew printing. It issued, almost simultaneously with the Marches and de Palasios edition, a copy of Berakhot with Seder Zera’im, possibly followed by Bezah.

Proops was unable to continue with his proposed Talmud edition, publishing one (two) volume(s) only. Judah Aryeh Loeb, relying on the approbations given his Talmud prior to the Proops edition, objected to the publication of a rival Talmud, and brought the matter before a rabbinic court. The court’s enjoined Proops from printing additional tractates, and trespassing on Judah Aryeh Loeb’s rights as a printer. To avoid further difficulties of this sort, Marques and de Palasios secured approbations from leading rabbinic authorities for their Talmud, prohibiting other printers from publishing a Talmud.

Rabbinovicz observes that Proop’s defense, that he was unaware that Samuel Marches and Joshua de Palasios were already engaged in the publication of the Talmud, was untenable. Proops had to know that R. Judah Aryeh Loeb was publishing tractates in Amsterdam. Proops might argue that he had begun Berakhot prior to the other press, was unaware of their approbations, and having begun, should be allowed to complete his work.

This was not the last law suit concerning the Talmud that Judah Aryeh Loeb had to contest. Although we can sympathize with Judah Aryeh Leib’s difficulties with Solomon Proops, there is a certain poetic justice to his situation, for just as he protested the Proops Talmud in Amsterdam, so too did he face objections from the Frankfurt on the Oder printer. As noted above, Michael Gottschalk, the Berlin and Frankfurt on the Oder printer, who had printed his first Talmud (1697-99) and would subsequently print two additional two editions of the Talmud (1715-22, 1734-39), brought a suit to force Judah Aryeh Loeb and the partners to cease printing their Talmud. In addition to his prior approbations Gottschalk claimed that he had obtained the sole authorization to print his second Talmud, again for twenty years, from Kaiser Joseph I of Germany in 1710, King Frederick Augusta of Poland and Saxony in 1711, Kaiser Karl VI and King Frederick Wilheim in 1715. Gottschalk filed his complaint in mid-1717.

Rabbinovicz writes that he does not know why Gottschalk waited so long to exercise his rights to stop the printing of this edition. Gottschalk had obtained royal permission, as well as rabbinic approbations, as early as 1715. Instead, he permitted Judah Aryeh Loeb to print a number of tractates over a period of several years before he acted. According to Friedberg, in that year, Samuel Schotten took tractates from the Amsterdam Talmud to the book fair in Lippsia (Leipzig).

There were several book fairs of importance in Germany, among the most important being those of Frankfurt on the Main from as early as 1240 and the Leipzig (Lippsia) fair, which predates it, from 1170. Both locations were centers of the printing industry, Frankfurt midway between north and south, Lippsia in the north. Although Frankfurt initially overshadow Leipzig, it later “was forced to yield to the Saxon city. . . . which became . . . the centre of German book publishing.” Leipzig’s importance can be further credited, “not in its number of presses but in its number of shops, its number of book dealers, and publishing houses.” Furthermore, although many German cities had book fairs, “Leipzig was one of the most important fairs eastern and south Eastern Europe and soon utilized the advantage of her connections for the development of the book trade.”[26] It is not surprising then, that Moses Schotten, the son of Samuel Schotten, attended the book fair.[27]

Returning to Friedberg’s account of events, Moses Schotten attended the Leipzig book fair, bringing samples of the tractates printed in Amsterdam. Gottschalk “waited for him and then ambushed him in secret.” Immediately after Schotten arrived in Leipzig Gottschalk contacted the fair officials, that the tractates brought by Schotten should be confiscated. The fair officials did not act, however, instead awaiting instructions from the prince of the district capital, Dresden, who delayed until the conclusion of the fair. In the interim, Schotten was able to sell the tractates that he had brought without hindrance.

Gottschalk returned home, bitter, and submitted a complaint on January 3, 1716 to the king. In it Gottschalk related what had occurred at the fair and petitioned the king for recourse against those who had trampled “with their feet” on his legal rights. The king responded to affirmatively to Gottschalk on February 12, 1716, prohibiting the sale of the Talmud at the fair by anyone except Gottschalk. Several additional tractates were printed in Amsterdam and Schotten returned, in October 3, 1717, to the fair. Gottschalk, when he became aware of this, informed the officials of their obligations and this occasion all the books (tractates) that Schotten brought with him were seized. Moses Schotten justified his actions, stating that he had come only as an agent of his father, Samuel Schotten, from Frankfurt on the Main. If the fair officials had complaints they should bring them to that city. Although Gottschalk was successful in preventing the sale at the fair and the further publication of tractates from this Talmud in Amsterdam ceased in 1717, his victory was short lived. Soon after Judah Aryeh Loeb was able to resume printing in Frankfurt on the Main, publishing a fine and complete Talmud.[28]

III

Frankfurt on the Main Talmud

Printing was relatively late in coming to Frankfurt on the Main, partly due to its proximity to Mainz, an early center of printing. The first Frankfurt printer was Beatus Murner, who printed nine books in 1511-12. Among those nine titles are the first books printed in Frankfurt with Hebrew letters, a 1512 editions of a Birkat ha-Mazon ‘Benedicite Judeorum’ (Hebrew in woodcut) and Hukat ha-Pesach ‘Ritus et celebrate phase judeorum’ by Beatus Murner’s better known brother, Thomas Murner, a Maronite brother and enemy of Martin Luther.

The printing of a significant number of Hebrew books begins in the last decades of the seventeenth century, in about 1675. Four hundred ninety titles, albeit some questionable, are ascribed to Frankfurt in the hundred-year period from 1640 to 1739.[29] Johann Koelner (1708–28), who published a complete Talmud (1720-22) is credited with more than one hundred titles, although that number includes each of the tractates in his edition of the Talmud.[30] This Talmud was initially the completion of the Talmud begun in Amsterdam in 1714 by R. Judah Aryeh Loeb together with Samuel Marches and Joshua de Palasios interrupted by the suit, based on approbations for his edition, brought by Michael Gottschalk

Judah Aryeh Loeb now attempted, successfully, to complete the Talmud he had begun in Amsterdam in Frankfurt on the Main. Given that Gottschalk, based on the approbations he had received for his second Talmud, was able to prevent publication of Judah Aryeh Loeb’s Talmud in Amsterdam, only three years earlier, how was Judah Aryeh Loeb able to publish a complete Talmud only three years later in Frankfurt? Friedberg writes, tersely, that “the eminent, the prominent R. Samson Wertheimer from Vilna, court Jew of Karl VI, influenced him to give Aryeh Loeb ben Joseph Samuel av bet din Frankfurt on the Main authorization to print a new edition of the Talmud. The sovereign acceded to his request and authorized publication of the Talmud in Frankfurt from 1720.”[31] Rabbinovicz remarks that the interruption in the work on the Amsterdam edition and the ensuing great expense, as well as the bribes in the courts until Aryeh Leib succeeded, left him in reduced financial condition, until Samson Wertheimer, became involved, making it possible to continue and publish this fine edition.[32]

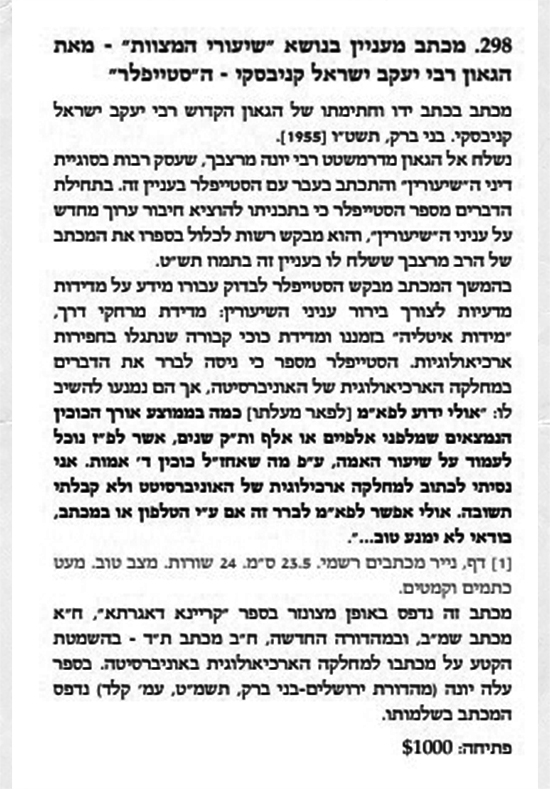

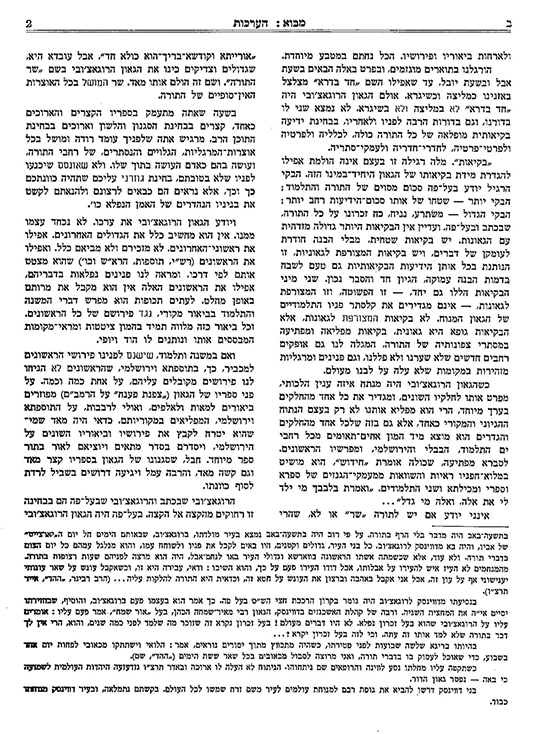

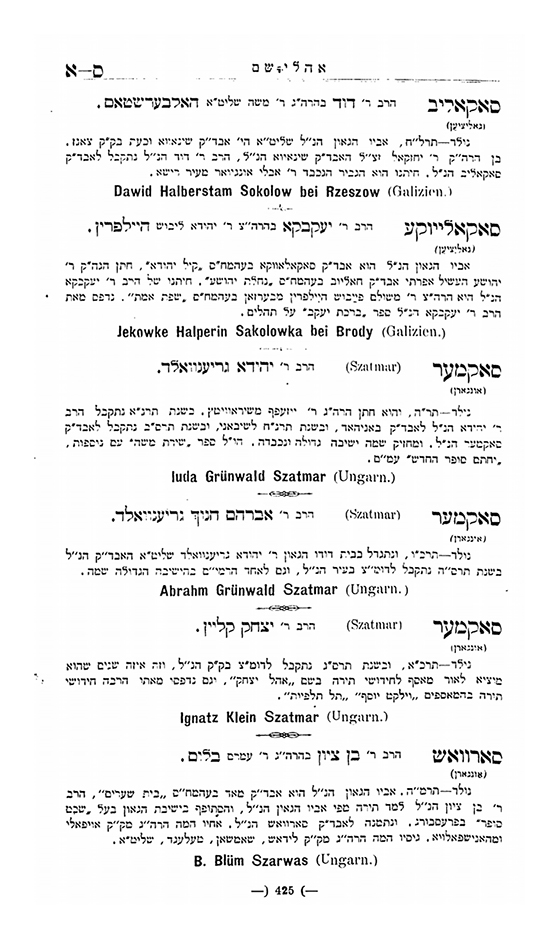

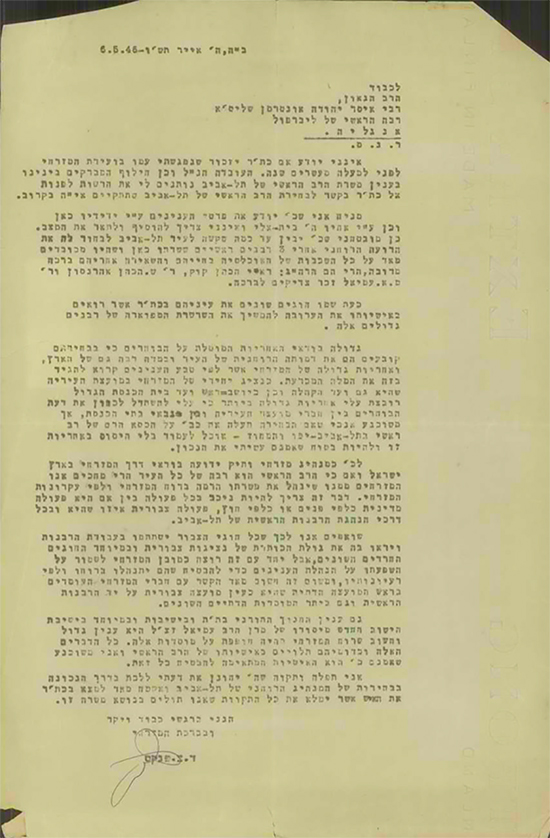

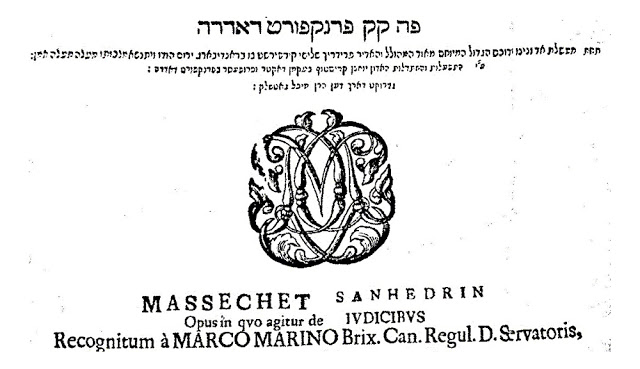

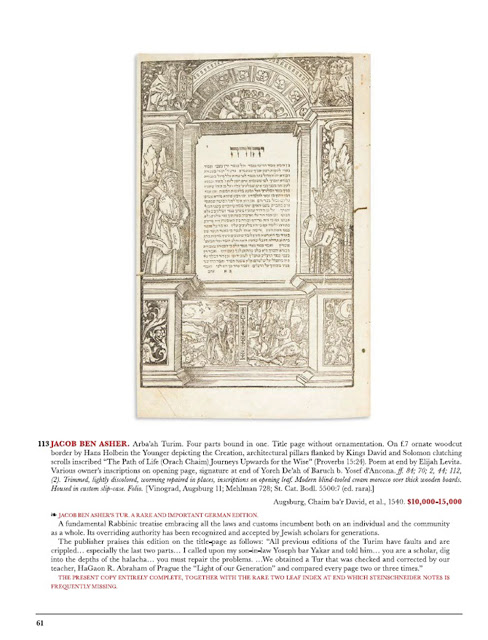

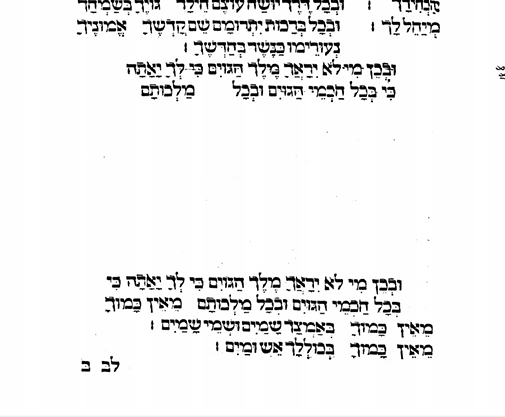

Fig. 6

Approbations were also published with this Talmud, primarily reprints from the Amsterdam edition and with one new approbation, from R. Jacob ben Benjamin Katz (Poppers, Shav Ya’akov) (1719). Another example of the continuity of the two editions is that the volumes issued in both cities are alike, the title pages showing minor textual variations only, such as the new place of publication, and on some but not all of the Frankfurt tractates, the inclusion of accompanying Latin text, confirming that it was printed in accordance with the text of the censor Marco Marino (Basle Talmud, 1578-81) and variations of the printer’s mark. Whereas the treatises printed in Amsterdam have a new woodcut of the Benveniste printer’s mark, the Frankfurt volumes, although retaining the outer crest with helmet, replace the lion and tower with the double headed eagle of the Hapsburgs (fig. 6).

Printing began in Frankfurt on the Main in 1720 with tractate Kiddushin, it having been anticipated that they would be allowed to bring the tractates printed previously in Amsterdam to Frankfurt. However, this was not permitted, so that they began to print the remainder of the Talmud, beginning with Berakhot completing the Talmud until Kiddushin that year, except for Seder Zera’im and tractate Ta’anit which were printed in 1722. Another possibility, suggested by Rabbinovicz, is that they were allowed to publicly sell the tractates printed in Amsterdam in Germany, but the market for the tractates printed in Frankfurt exceeded expectations, so that, to complete sets of the Talmud it was necessary to reprint those tractates printed earlier in Amsterdam.[33]

IV Aftermath

The next controversy over rival editions of the Talmud occurred with the second printing of the Talmud by the Proops’ press in 1752 – 1765. This edition, published by Solomon Proop’s sons, Joseph, Jacob, and Abraham, is a large, very fine folio edition. Publication was interrupted for several reasons, but primarily due to the publication of rival editions of the Talmud in Sulzbach by Meshullam Zalman Frankel and afterwards by his sons, Aaron and Naphtali, that is, the Sulzbach Red (1755-63) and the Sulzbach Black (1766-70). The first Sulzbach Talmud is known as Sulzbach red because the first title-page in the volume was printed with red ink, in contrast to Sulzbach black, in which the first title-page in the volume is printed entirely in black ink. Both the red and the black are smaller folio and not highly regarded.

Resolution of the dispute between the two publishing houses was settled by a rabbinic court that determined, among its findings, that despite Proops’ prior approbations the Sulzbach printer did not have to desist from publishing, for the Sulzbach Talmud was less expensive and therefore available to individuals who could not afford the larger and finer Amsterdam Talmud, the latter marketed to a more affluent market.

One other dispute of significance, that embroiled leading rabbis in Europe, was over the rival editions of the Talmud printed by the Shapira press in Slavuta and the Romm press in Vilna of their respective editions of the Talmud in 1835. Both the Amsterdam-Sulzbach and Slavuta-Vilna disputes are beyond the scope of this article. However, they, as well as the controversy surrounding the Frankfurt on the Oder and Amsterdam editions of the Talmud, the subject of this article, confirm Raphael Natan Nuta Rabbinovicz’s observation as to the negative and disruptive results of restrictive approbations.

Even though the intent in granting approbations was for the good of the community, to insure investors a reasonable return on their investment, the result, as noted above, was detrimental. The Talmud was printed only eight times in the century from 1697 to 1797, and the price of a set of the Talmud was dear. Prior to that the Talmud had been printed several times in Italy and Poland within a relatively short period of time, the primary impediment then being the opposition of the Church and local authorities. After 1797 the use of restrictive approbations declined, with the consequence that within four decades the Talmud was printed nine times, this notwithstanding the Slavuta-Vilna rivalry. Given these controversies and their negative outcomes, perhaps a better course for all would have been to apply Hillel’s admonition in Avot.

Be of the disciples of Aaron, loving peace and pursuing peace.

(Avot 1:12)