Some Assorted Comments and a Selection from my Memoir, part 2

by Marc B. Shapiro

1. In a recent Jewish Action (Summer 2009), p. 21, Elli Fischer writes:

Brandeis University has been enclosed by an eruv for thirty years, longer than any other campus not adjacent to an established Jewish community. Since Brandeis is a Jewish institution, the eruv is funded by the university (as opposed to the students). . . . Rabbi David Fine, who graduated from Brandeis in the mid-1980’s, recalls checking the eruv as a student. . . . The first two JLIC rabbis to serve at Brandeis, Todd Berman and Aharon Frazer, each implemented minor upgrades to the eruv.

This gives me the opportunity to correct some errors and tell part of the story of the Brandeis Orthodox community. The eruv was first established in the 1982-1983 school year, when R. Meir Sendor was the Orthodox advisor. (Sendor is currently the rabbi of Young Israel of Sharon and is unusual in that he is both an academic scholar of Kabbalah, with a PhD from Harvard,

[1] and also involved in Kabbalah from the spiritual side.) Rabbi Sendor informs me that Rabbi Yehudah Kelemer was the initial halakhic advisor, and Rabbi Shimon Eider was later brought in to be the official rav ha-machshir. (R. Eider later helped in putting up the eruv in Sharon, which was the first eruv in New England.)

When I arrived in Brandeis in the fall of 1985 we did not carry on Shabbat. (Contrary to the Jewish Action article, David Fine didn’t arrive at Brandeis until two years later.) I assume that due to some structural changes on campus, the eruv was no longer functional. During that academic year, Rabbi Eider returned, did what needed to be done, and the eruv was once again kosher. At this time, R. Yaakov Lazaros, a Chabad rabbi in Framingham (with semichah from R. Moshe Feinstein), was the Orthodox advisor.

The university paid (and I assume still pays) for the eruv’s upkeep, but this has nothing to do with Brandeis supposedly being a Jewish institution. In fact, it is not a Jewish institution. Brandeis paid because it saw this as an important service to the Orthodox community. The university has expanded since the 1980’s so that is probably why changes to the eruv had to be made. I don’t like the word “upgrade” that Fischer used, because “upgrade” means to improve the quality of something, and I don’t think that Rabbi Eider’s eruv needed to be improved.

When one speaks of Orthodox life at Brandeis, a lot of credit must go to Rabbi Albert Axelrad, who was the Reform Hillel rabbi at Brandeis. He is someone who over time I came to admire greatly, even though our religious outlooks were so very different. What Weinberg jokingly said about another Reform rabbi applies equally to Axelrad: He is a “

hillul ha-shem,” (

hillul ha-shem in quotation marks!) because he shows that “one can be an upstanding and noble man, full of the spirit of love for Israel, its Torah, and its language,” even if one is not a halakhic Jew.

[2]In ways that people don’t realize, Axelrad greatly assisted Orthodox growth on campus, and today Brandeis has a very large Orthodox contingent.

[3] It was Axelrad who made sure that there would be an Orthodox advisor on campus, paid for from the Hillel budget. Yet despite his leaning over backwards to help the Orthodox, there were always those in the Orthodox community who had negative feelings towards him, not only ideologically, but also personally. These were people who came from yeshivot and had never had any contact with a Reform rabbi, and here was one who performed intermarriages. Axelrad had also been involved in some leftist causes and has the dubious distinction of having been officially put into herem, ceremony and all, by Rabbi Marvin Antelman. He shared this honor with the entire membership of the New Jewish Agenda, whom Antelman also placed under herem. (I mentioned Antelman in a previous installment and hope to return to him as his books are deserving of their own post.)

Rabbi Lazaros was only at Brandeis for one year and he was followed by Rabbi Marc Gopin. Those who saw the video on the Rav will probably remember Gopin as he has a few appearances in it. At the time he was working on his dissertation, which focuses on Samuel David Luzzatto.

[4] He has also published a nice article on Elijah Benamozegh.

[5] Since then he has made an international reputation for himself in the area of conflict resolution, travelling widely and publishing a number of books.

[6]Gopin was followed by another rabbi, a RIETS graduate, who would have been very good for the community in another ten years. But at this time he was too much to the right for them. The community had always been a somewhat liberal place. I recall the outrage among many when R. Moshe Dovid Tendler came to campus and expressed his feelings about homosexuality. There was the same outrage when the new campus rabbi said similar things. (Shmuley Boteach or R. Chaim Rapoport would have been more in line with the students’ feelings.) The following should give a further sense of the liberal nature of the community: The practice on Shabbat morning when taking the Torah out of the ark was for the hazan to carry it through the women’s section. This struck everyone as a very nice thing to do, and although it is not done at the typical synagogue, college is a very different place. Another example of how college differs from the “real world” is that during Shabbat morning services women routinely give divrei Torah, yet this is not something that most “regular” shuls are willing to allow.

When Rabbi Lazaros was the Orthodox advisor he ruled that the practice of carrying the Torah on the women’s side was forbidden. From the way he explained his decision I understood that the major issue wasn’t carrying the Torah on the woman’s side per se, but rather women kissing the Torah. As he was the rav, we had to listen to him, even on the Shabbatot that he was not there. However, in an act of rebellion the community made a decision that when the Torah was taken out of the ark the hazan, who now could not walk around the women’s side, would also not walk around the men’s side. He would bring the Torah right to the bimah. When the Torah was returned to the ark the hazan walked to the front of the synagogue and sang Mizmor le-David, once again without walking around the men’s side. The following year, with the arrival of a new Orthodox advisor, the community revived the old practice of carrying the Torah on the women’s side.

When I was the Orthodox advisor in the early 1990’s the Orthodox culture on campus had changed, and the situation with carrying the Torah was exactly reversed from what it had been in the 1980’s. In the 1990’s it was the students, or rather some students, who wanted to stop carrying the Torah on the women’s side. They didn’t think that an Orthodox shul could have such a practice. My position was that the minhag had to remain the way it was. At that time there was a very dynamic Ramah-type minyan and if the Orthodox were seen as too close-minded we would lose people to the Conservative minyan. In fact, it was precisely because of the liberal nature of our minyan that many non-Orthodox were attracted to it, and a number of students adopted an observant lifestyle while at Brandeis. While some students, coming to Brandeis after a year in Israel, wanted the minyan to be just like their shul in Teaneck and the Five Towns, the truth was that the minyan, to be successful, had to be run like an out of town shul.

This was not the only time I felt that for the sake of the wider appeal of the Orthodox community I had to make decisions that got some people upset. On Friday night there was a communal meal for all the different denominations. Often a woman would say kiddush. After that everyone could, of course, make their own kiddush. But there were some people who wanted to make a big deal about the women saying kiddush, and were also saying that men are not yotze with this, no matter which woman is reciting the kiddush. At the same time that this was happening, there were also those in the non-Orthodox groups who wanted to start having women lead the communal birkat ha-mazon. Until then, out of deference to the Orthodox, only a man led it.

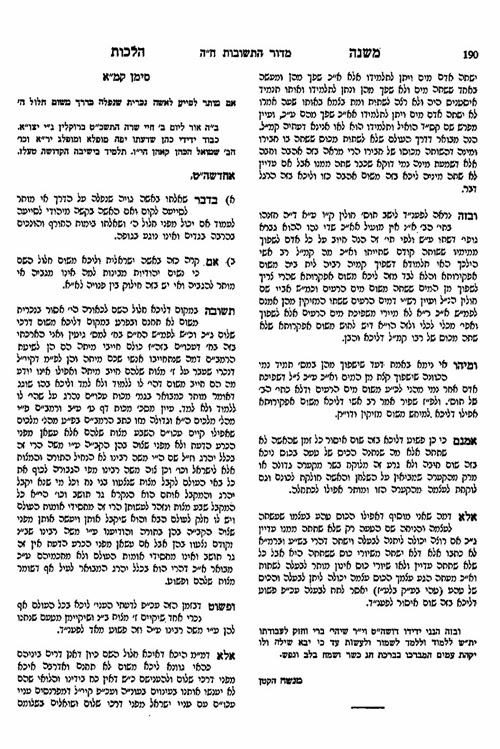

We have a talmudic principle that if you try to grab too much you will end up with nothing, so I had to make a choice. The real halakhic issue here was

birkat ha-mazon, as a woman cannot be

motzi a man

.[7] Therefore, I told the students that it was OK for the women to make kiddush but not

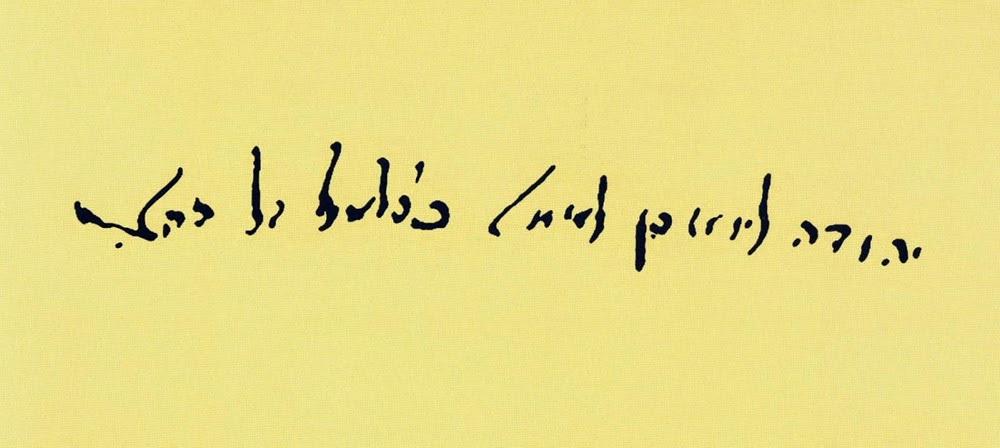

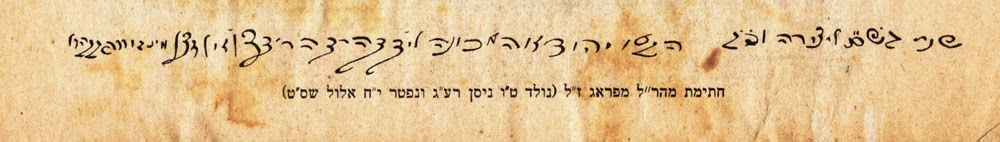

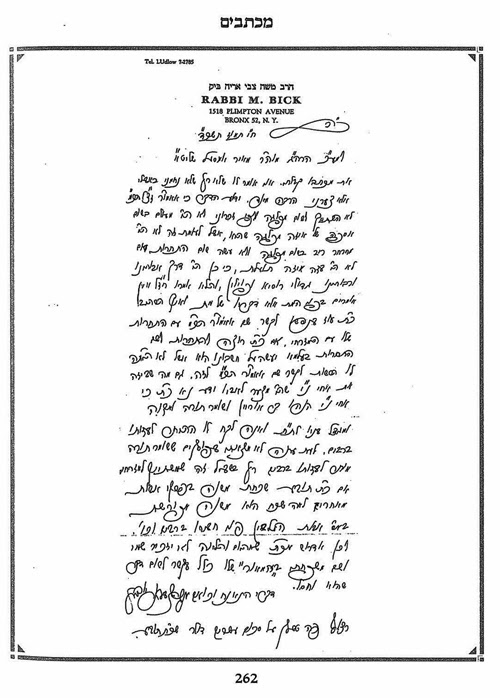

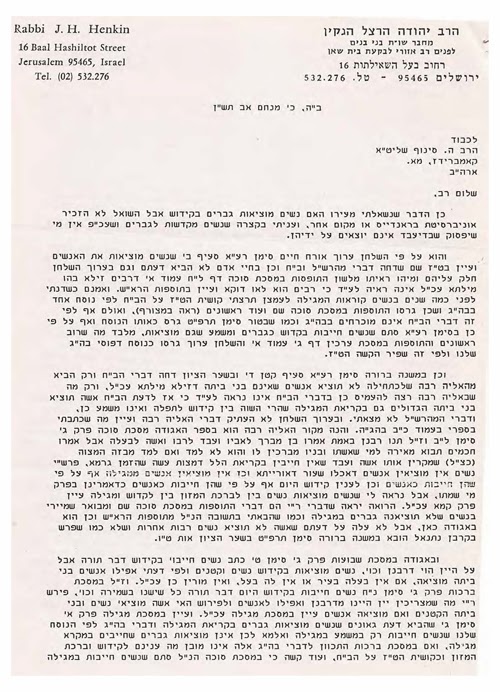

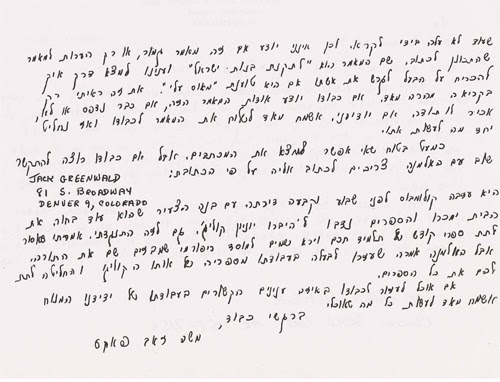

birkat ha-mazon, and anyone who wanted to should make his own kiddush. This compromise was accepted. A year prior to this, before I was working at Brandeis, I had been wondering about this issue and asked R. Yehudah Herzl Henkin if it was permitted for a woman to say kiddush for a man. He replied in the affirmative. Shortly after receiving his answer, the same issue became pressing at Harvard Hillel. I told the Orthodox rabbi at Harvard, Harry Sinoff, what the practice at Brandeis was and that he might want to consult with R. Henkin. This is the responsum R. Henkin wrote, published here for the first time. (See also

Bnei Vanim, vol. 2, pp. 40-41.)

I myself wrote a short Hebrew “mini-responsum” dealing with women, kiddush, and birkat ha-mazon. It was taped to the wall of the campus beit midrash, but with the move to the right, I am sure that not too long after my departure the responsum came down.

I just mentioned the Brandeis beit midrash, which it itself significant. Other than Brandeis, I don’t know if there is another secular university in the world that has a beit midrash in a university building. When the beit midrash was established in the early 1990’s it was a great achievement. It was an entirely student led project, but again, Rabbi Axelrad’s involvement, behind the scenes, was crucial. He spoke at the beit midrash dedication, as did the Boston Rosh Kollel.

There were also some minor conflicts related to the beit midrash. Although it was the Orthodox students who arranged for it, it was obviously something that all students could be part of. The question came up of what type of books should be stocked there. My feeling was that since the library had all the scholarly and academic books, there was no reason for these sorts of texts to be in the beit midrash.

Another issue arose with the Boston kollel. They had recently become involved with Brandeis students as part of their outreach. One of the kollel guys, who was having a great influence on the students, wanted to start a gemara shiur on campus. This was fabulous. He wanted to give the shiur in the beit midrash, which was the natural place. However, he said that he could only do it if no women were allowed into the beit midrash during this time (even if they were not participating in the shiur). One of the women students complained to me, and I agreed that this was improper. The beit midrash was established for all students and must be open 24 hours a day for everyone. We could not have a situation where, like a pool, the beit midrash is closed to women for certain hours. It also went against the ethos of the community to declare that women are barred from attending certain classes. I told the male students who were organizing the shiur that it would have to take place somewhere else, and that is what happened.

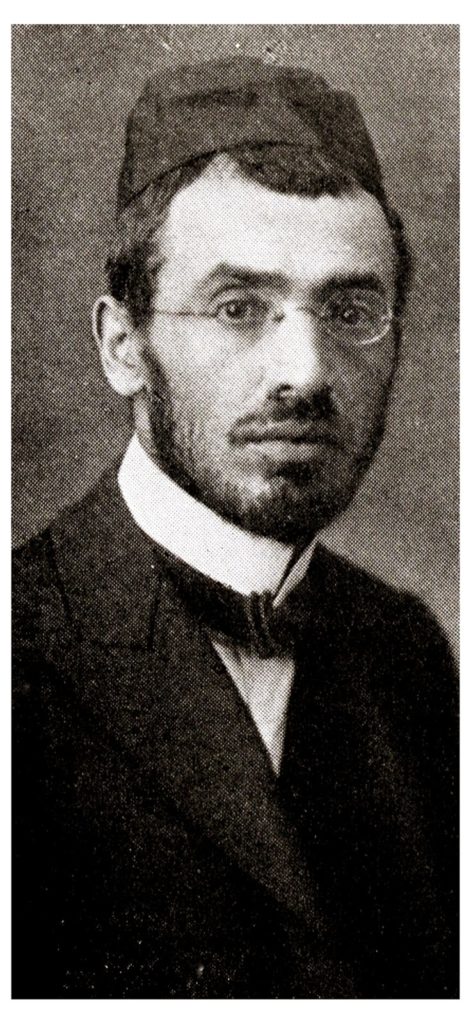

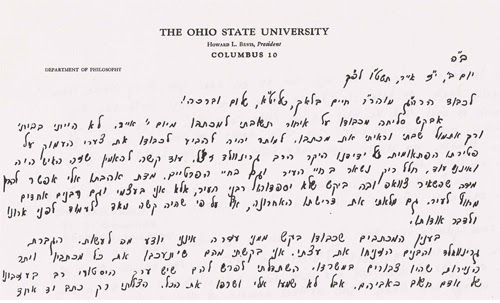

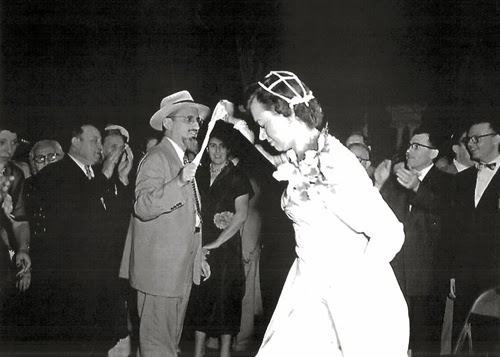

Right when we were having the discussions one of the students drove to Brookline to attend Prof. Isadore (R. Yitzhak) Twersky’s gemara shiur, and he came back reporting that there was a woman in attendance. If the Talner Rebbe welcomed women to his shiur, were the Brandeis students supposed to be more “frum”? For those who have never seen a picture of my late teacher, who was also the son-in-law of R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik, here he is:

There was another time when the Boston Rosh Kollel gave a decision to some of the students that I felt could drive away the less religious if it was adopted by the community as a whole. Since there were students who thought that the Rosh Kollel should be regarded as the halakhic authority for the community, I was in a difficult situation. This was especially so as I myself had asked him questions in the past, so it would not be an easy thing to reject his ruling in this case. I consulted a well-known haredi posek with whom I had discussed other matters, including an issue of possible mamzerut that came up on campus. He agreed with my position but said that he could not put his decision in writing.

I know that some people will find this objectionable, but it never bothered me. Why should I care if he put it in writing? He knew that if he did he might be attacked. Given the choice between no pesak (if it has to be in writing) or an oral pesak, obviously the latter is preferable. Although at the time I told people who gave the pesak (and anyone who wanted to could call him up to confirm it), revealing it on this blog would, I think, fall into the category of “putting it in writing.” This posek is still functioning, and if he was afraid of being attacked fifteen years ago, all the more so today. (There are reasons why I am being vague about the particulars of the pesak.)

Returning to the Brandeis beit midrash, Prof. Marvin Fox also spoke at its dedication. This was significant as it was the first time, in my memory, that the students took advantage of this great scholar and talmid hakham.

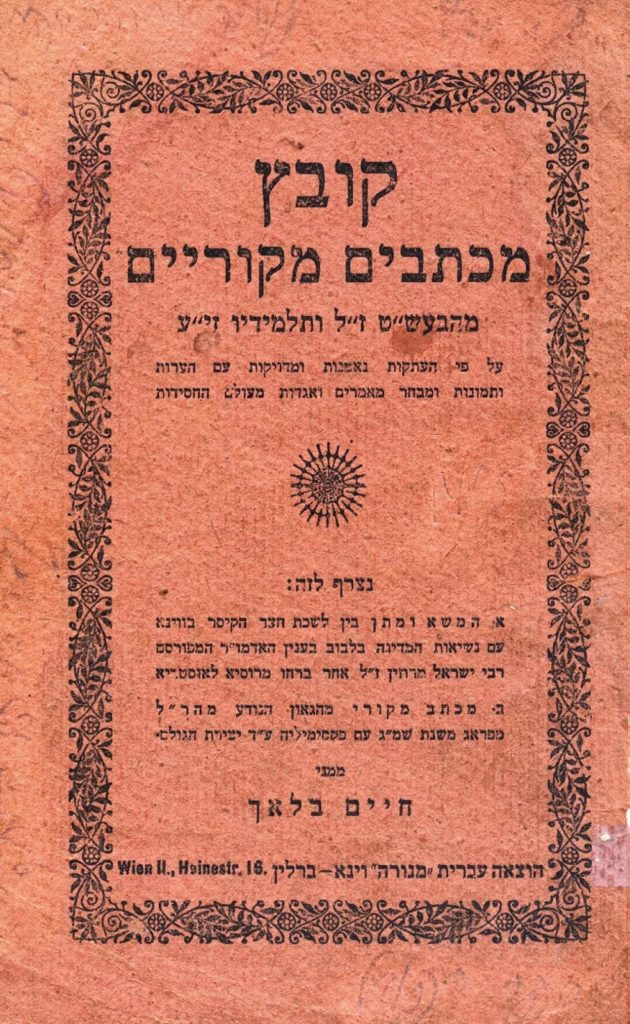

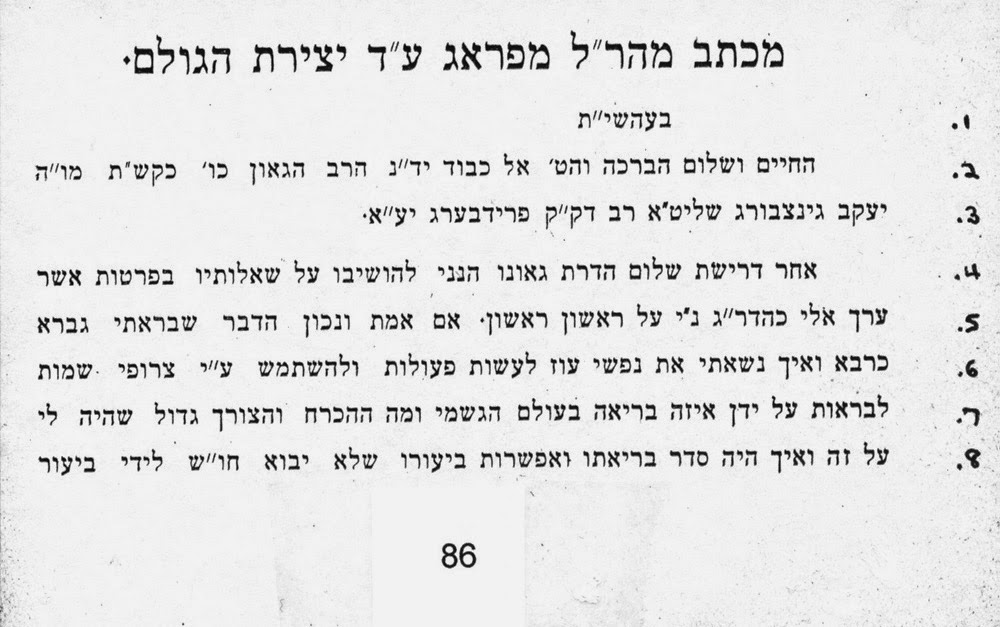

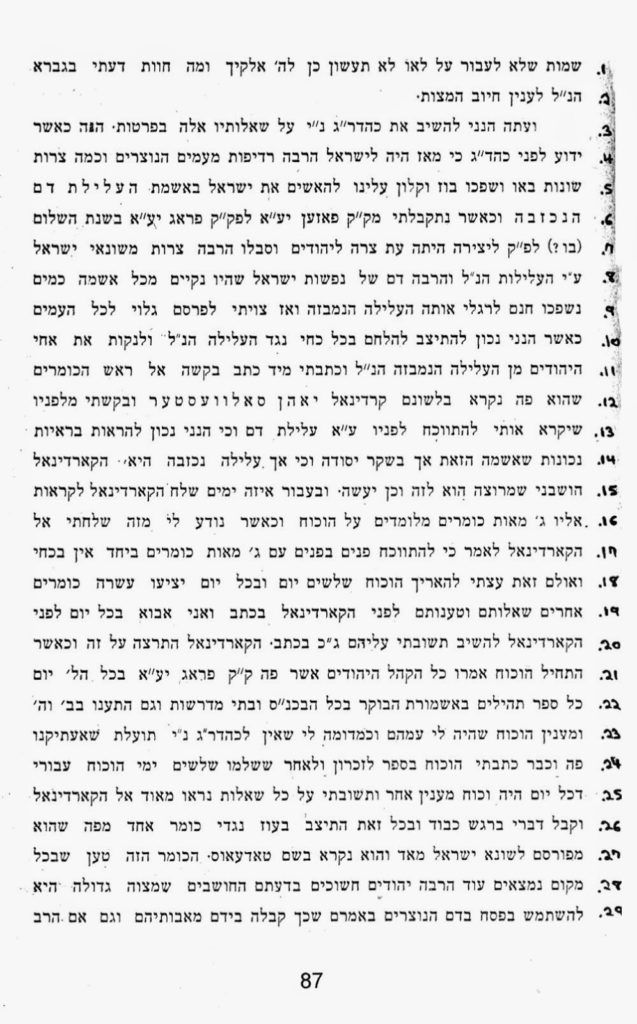

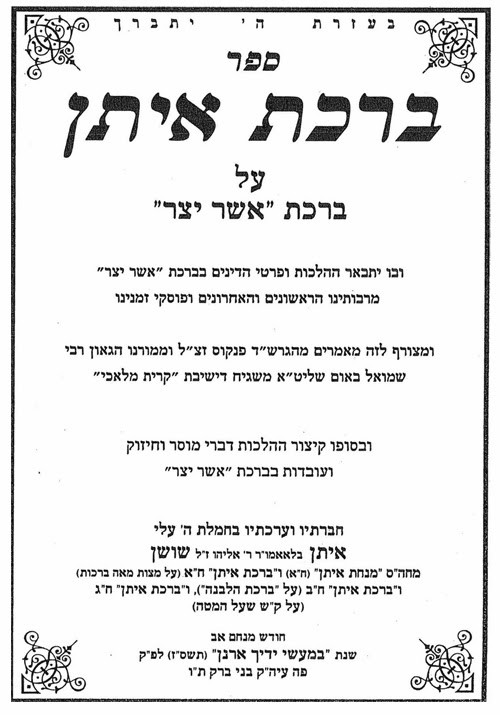

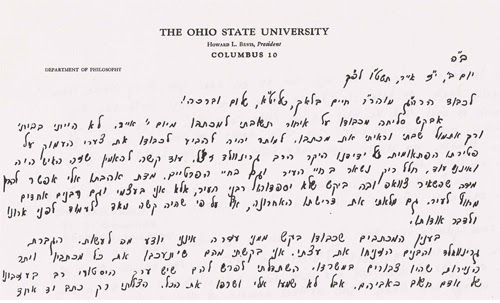

[8] There was such a disconnect at Brandeis between the academic life and the religious life that regarding the latter we all overlooked the people in our midst, those who were teaching us in the classroom. I too regret not speaking to Fox in greater detail. For example, having lived in Columbus, Ohio he knew R. Leopold Greenwald very well, and yet other than hearing one or two stories about him from Fox, I never took the time to find out more. Fox also knew Chaim Bloch, the great rabbinic forger. (Greenwald and Bloch were themselves good friends.) He told me once that there was a lot he could say about Bloch, and yet I was foolish and never took advantage of this.

After Fox’s death I discovered a letter from him to Bloch in which he explains how it happened that Greenwald’s great library ended up at the Hebrew Union College. He also tells us the tragic fate of Greenwald’s huge collection of letters, letters that he received from gedolim and scholars over the course of many decades. This must have been one of the largest and most interesting collections in the world, full of priceless material which should have been given to a library so a Greenwald archive could be established. Among these papers were also to be found manuscripts from Greenwald’s own pen that had not yet been published. It was perhaps with this in mind that Fox told me very firmly, at the Brandeis beit midrash dedication, not to let the letters of Weinberg out of my hands. He was convinced that some people would want to destroy them, or at the very least make sure they were not made public.

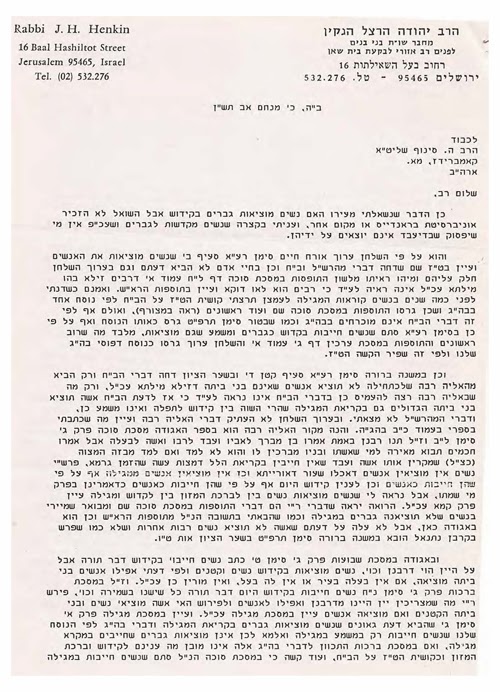

Here is Fox’s letter to Bloch, courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute, New York

[9]:

Returning to the RIETS graduate who was the Orthodox advisor following Gopin, there were a few issues that created problems. Yet the straw that broke the camel’s back was that, in accordance with R. Moshe Feinstein’s pesak, he would not give an aliyah to Rabbi Axelrad. Axelrad’s practice was to come to the Orthodox minyan once a year. Not giving him an aliyah was something that simply wouldn’t fly at Brandeis. It was not a question of Axelrad being concerned about his kavod. I am certain that he did not take personal offense. But he was very concerned about what appeared to be a growing split in the community, a community that had always gotten along so well. To publicly refuse to give the Hillel rabbi an aliyah would give the Orthodox community a sectarian flavor very much removed from both the Hillel ethos, as well from the majority of Orthodox students as well. It was not surprising, therefore, that this rabbi was let go in the middle of the year. After he was let go he tried to create a separate Orthodox community independent of Hillel. It was to be a real Austrittsgemeinde, and he told us that money would be forthcoming from New York to help us form the new community. Yet none of the students were interested.

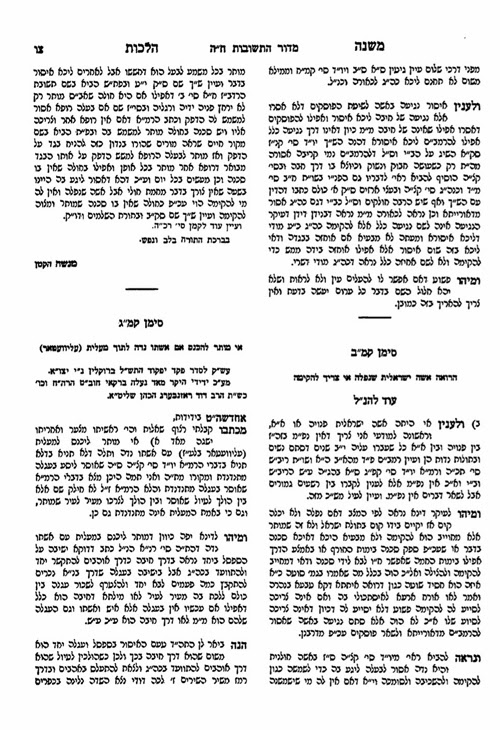

R. Yehudah Herzl Henkin’s responsum, Bnei Vanim, vol. 2, no. 9, on whether one can give a Reform rabbi an aliyah, is dealing with the Brandeis situation (and was sent to me). Rabbi Henkin’s responsa have an unfortunate characteristic in that they don’t mention to whom he is writing, or give other identifying details. Without this blog post, future historians would have had no way of knowing which of the many American campuses he was referring to. Think of how much we learn about the history of Orthodoxy in America from R. Moshe Feinstein’s responsa. We see him answering questions to Canton, Berkeley and all sorts of other places. Knowing to where he is writing is vital for getting a sense not only of Orthodoxy of the time, but of the responsum itself, since his ruling for an out-of-the way place cannot always be applied when dealing with a center of Jewish life. More leniencies are obviously found in the former. With regard to Bnei Vanim, since R. Henkin doesn’t tell us to whom he is writing, when he is offering comments on another’s work we have no way of identifying this text if we want to get a better sense of the opposing position. (Other poskim have also published responsa that deal with Brandeis, and I will discuss them in a future post.)

I think readers might also find the following story interesting, from my tenure as Orthodox advisor at Brandeis. Every Friday night all the different groups on campus would get together for an oneg, at which there would be a speaker. Out of respect for the Orthodox a microphone was never used, which wasn’t really an issue since the onegs were not that big. However, it so happened that Hillel had an opportunity to bring in Dr. Ruth Westheimer

[10] to speak on Friday night. She wasn’t going to speak about any sexual matters, but about her early years in Germany and her family that was killed.

This was at the height of Dr. Ruth’s fame, and there was going to be a huge crowd to come hear her. Hillel had decided to break with tradition and use a microphone at the event, which was to be held in a hall much larger than was usually used. I was told that Dr. Ruth actually insisted on the microphone, and the Hillel leadership didn’t feel like they could refuse. Before continuing with the story, let me go back a few years and tell how I, and my classmates, first heard of Dr. Ruth, because I think it says something about how yeshiva administrators are sometimes very foolish. I still remember how one day on the bus all the talk was about how the administration of Bruriah High School – the girl’s school of the Jewish Educational Center in Elizabeth, where I was a student – had sent out a letter to all parents telling them about a very dangerous radio show called “Sexually Speaking” that was on very late on Sunday night. The parents were told to make sure that their daughters didn’t listen to it—as if a parent can control what a teenager does with her radio in the privacy of her room. It was an era before computers, when we all listened to radio. (I am sure many readers remember the days when 770 WABC played music.)

Now anyone should realize that the perfect way to bring teenagers to do something is to tell them that they can’t do it. Although perhaps none of the Bruriah students had ever even heard of the show, upon receipt of this letter they all were determined to find out what the administration wanted to keep them away from. Not only that, but on the bus, the day after the letter was received, they told all the boys about this strange letter. None of us had ever heard of Dr. Ruth, and our school never sent out a warning letter to parents. Yet you can be sure that after hearing the news we too were curious. It happens that some students found Dr. Ruth so funny and interesting that they listened to her while they were on the phone together. The whole novelty was about an older Jewish woman, with a strong accent, speaking so openly about the things people don’t usually speak about.

Returning to the story, I was now put in a difficult situation, since the Orthodox community could not support an event that involved Sabbath violation. I told this to the Hillel administration and I told the students that I would not be going and it was not something that the Orthodox community could be part of. I remained in the dining room with those students who chose to stay, and those who wanted to hear Dr. Ruth went upstairs, where the event was taking place. Imagine my surprise when someone sits down next to me, and lo and behold, it is Dr. Ruth. She had obviously been told that there was some controversy about her speaking on the microphone, and she wanted to come speak to me. She was extremely apologetic, and said that unfortunately she needs the microphone, otherwise no one would be able to hear her. She also told me that she was sorry that this created problems for the Orthodox community. Dr. Ruth stayed with us for about ten minutes or so, and even bentched together with us (though though she hadn’t eaten anything!). She told me that she remembered singing the standard tune to the first paragraph of birkat hamazon when she was a child in Germany. I don’t know if she had sung it since.

One other event is worth recalling, and this took place when I was an undergraduate. It involved a dispute between me and my friend David Bernstein, and I would be curious to hear what readers have to say.

[11] We decided to create an organization so we could invite in speakers. In order to get money from the university, we had to be officially chartered, so in our senior year we created the Brandeis chapter of Young Americans for Freedom. It had exactly two members (we had no interest in having any others join), and lasted for only one year (i.e., until we graduated). I was a little surprised when the Brandeis student senate agreed to charter us and give us money, but hey, you don’t look a gift horse in the mouth. (Had Matthew Brooks not already graduated, we probably would have let him join our little club. Brooks is now the executive director of the Republican Jewish Coalition. See

here)

One of our events was sponsoring a debate between my father, Edward S. Shapiro, and Stephen S. Whitfield on what political ideology was more in line with Jewish interests. This had a very large turn-out and the problem was that Whitfield, although a Democrat, is more of a Truman or Kennedy Democrat. Every time my father cited some nonsensical statement by a Democratic figure, Whitlfield agreed that it was nonsense, so they ended up agreeing about as much as they disagreed. A debate isn’t much fun unless one of the speakers is prepared to defend what others regard as indefensible (e.g., anyone looking to defend ACORN?).

For those who don’t know, Whitfield is one of the leading experts on American Jewish culture, having written an enormous amount on the topic. My father started off as a general historian, but has also written a great deal on American Jewish history. I can’t help thinking that the reason the

New York Times never reviewed his book on the Crown Heights Riots

[12] – which was a National Jewish Book Award Finalist – was that they didn’t want to revisit the issue. It was, after all, the great embarrassment of the Dinkins administration, and the symbol of Democratic failure in New York City, ushering in the Giuliani era. Yet it was, precisely for these reasons, one of the most important events in recent New York City history, and one would think that the

New York Times would have thought it worthwhile to review such a book. But no, they let it pass without comment.

We also brought in Dinesh D’Souza to speak. This was before he had published any of his books. In fact, I had never even heard of him when Bernstein suggested we bring him. His talk, though sparsely attended, was quite good. My dispute with Bernstein happened regarding our next speaker. I wanted to bring Lew Lehrman to speak. He was a prominent conservative who almost became governor of New York. He also had some honorary role in Young Americans for Freedom. Bernstein strongly disagreed. He argued that since Lehrman had converted to Catholicism a few years prior, he was not the sort of person we should be asking to speak. Although Bernstein was not Orthodox, that was a big issue for him and I agreed to drop the idea. But from my perspective, the fact that Lehrman had left the fold had no relevance for me in terms of having him speak. I wasn’t giving him an honor or asking him to speak on his theology. I wanted to hear him talk about economic matters and the situation in Nicaragua, and didn’t think that his personal life was of any relevance.

Although the cases are obviously not identical, there was a time when many people would have reacted the same way to inviting an intermarried speaker, and my response would have been the same. Since there is such a high intermarriage rate, one day most of us will have someone running for Congress in our district who is intermarried (some already have such representatives), just like most of us already know people, or have family members, who are intermarried. I don’t think this should have any relevance on my vote. In fact, I don’t think it should have any relevance on anything. Two generations ago, anyone who intermarried realized that he was doing something very much at odds with Jewish life and upbringing. Today, hardly anyone who grows up in the non-Orthodox world thinks that it is an issue at all, and it is only a matter of time before the Conservative movement accepts intermarriage. They have no choice, as their congregations are full of people whose children intermarry, and they can’t go on forever taking a hard line on this issue. Not only do they lose the intermarried children, they often lose the parents when the rabbi tells his long-time congregants that he is sorry but he can’t perform the wedding of their children or even announce it in the synagogue newsletter. I predict that within ten years we will see Conservative rabbis doing intermarriages.

The massive intermarriage rate has also impacted the Orthodox world. A number of years ago R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg stated that he thought that it might be a good idea for a father whose son was going to intermarry to attend the wedding, thus not completely cutting off all ties.

[13] Weinberg had known the problems of intermarriage very well, as the son of his good friend R. Shlomo Aronson, Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv, had married a non-Jewish Russian woman. He also knew Jacob Klatzkin, the brilliant philosopher and Zionist thinker, who was the son of the even more brilliant R. Elijah Klatzkin. How many people know that Jacob Klatzkin intermarried?

According to Gotthard Deutsch, R. Esriel Hildesheimer’s son Levi intermarried.

[14] It is hard to imagine that Deutsch, who was Levi’s contemporary, was mistaken with the facts, especially since he was never corrected in succeeding issues of the newspaper in which he published this information. Yet Dr. Meir Hildesheimer has told me that Levi Hildesheimer married the daughter of Abraham Brodsky of Odessa, the well known philanthropist. Levi’s son, Arnold Hildesheimer, was an active Zionist who made his living as a chemist and eventually moved to the Land of Israel. Arnold’s mother was definitely Jewish. Therefore, I don’t know if Deutsch erred or if Levi married twice.. Arnold Hildesheimer’s son was Wolfgang Hildesheimer, an important figure in pre-World War II German literature.

Unfortunately, we have a number of examples of not merely intermarriage of children of great rabbis, but even conversion. The story of the son of R. Shneur Zalman of Lyady is well known, and I don’t need to repeat it here. Let me just mention, however, that the man was clearly mentally unbalanced. Michael Bernays, a son of Hakham Isaac Bernays, is probably the most famous apostate from a rabbinic family in modern times, converting seven years after his father’s death. Another son of Hakham Bernays, Jacob, actually sat shiva when this occurred.

[15] If we want to look at descendants of great rabbis who converted, then the family tree of R. Akiva Eger has plenty of non-Jews. In fact, a predecessor to R. Akiva Eger as rav of Posen, the

Beit Shmuel Aharon, R. Samuel ben Moses Falkenfeld,

[16] had a most significant great-grandson, yet he was not Jewish. I refer to none other than Leon von Bilinski.

[17] He was Austrian minister of finance and also military governor of Bosnia when Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated.

I assume the famous Posen family got its name from the city of Posen. R. Gershon Posen, the dayan of Frankfurt’s separatist community, had a grandson who was on the verge of converting to Christianity. Nahum Glatzer describes this young man’s disillusionment with Orthodoxy, and how he tried to talk him out of conversion.

[18] (The conversion never took place, and another grandson, R. Raphael Posen, tells me that the more than seventy grandchildren of R. Gershon all remained Orthodox.)

How are Orthodox Jews supposed to relate to those who intermarry, and who typically don’t know any better? Many of us have even been invited to intermarriages. R Yuval Sherlow has stated that while it is not permitted to attend an intermarriage wedding ceremony, there are times (especially when family is involved) that it would be permitted to attend the party.

[19] R. Ovadiah Yosef has ruled that it is permitted to give an intermarried man an aliyah,

[20] and this opinion is also shared by R. Baruch Avraham Toledano and R. Pinchas Toledano (former Sephardic Av Beit Din of London).

[21] I am also told that this is the practice at the Lakewood kiruv minyanim all over the country. This is so despite the fact that the most that R. Moshe Feinstein would permit in such a case is to allow the intermarried man to open and close the Ark.

[22] It is actually Aish Hatorah that has done more to “normalize” intermarriage than any other organization in the Orthodox world. Not only does Aish Hatorah do outreach to the intermarried (something we can all appreciate), but they use various intermarried Jewish celebrities in their publicity, and have even honored these people at their events. I am not saying that they are wrong in what they do. After all, the old approach to intermarriage doesn’t work today, and although I find something distasteful about using an intermarried celebrity as the poster-boy to invite people to a Torah class, I see how people can disagree. But about one thing there can be no doubt, and that is that R. Aaron Kotler would be turning over in his grave if he saw what this supposedly haredi organization has done when it comes to tacit acceptance of intermarriage.

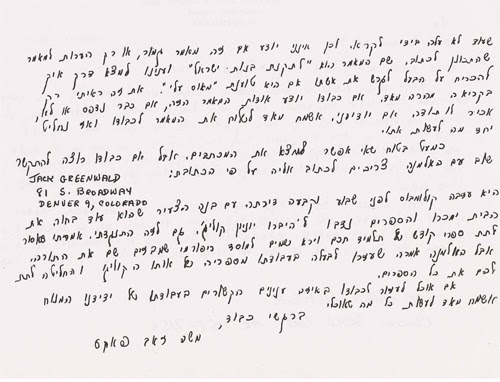

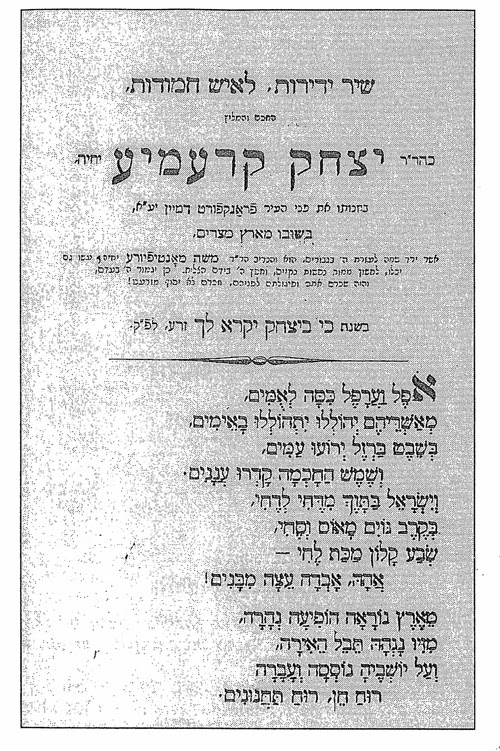

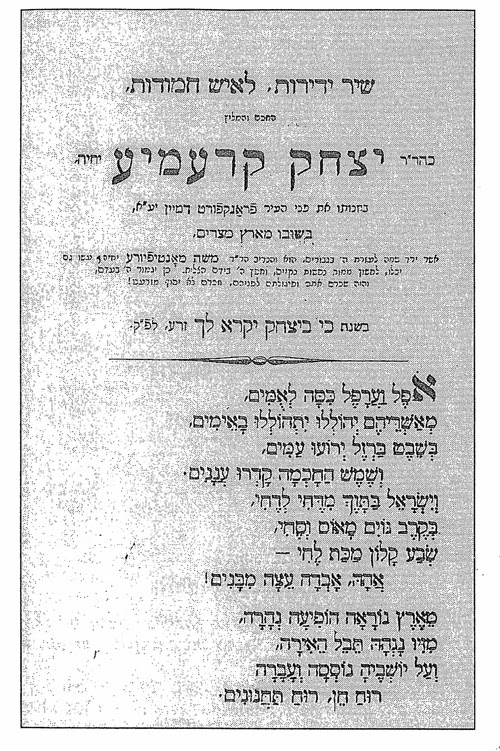

Yet we shouldn’t assume that it is only in modern times that intermarried people have been honored by Orthodox Jews. While it would have been unimaginable in previous years to put them on a pedestal the way Aish Hatorah does, there were times that the intermarried man did such great service for the Jewish community that it was only proper to express feelings of gratitude. Adolphe Cremieux is one such example. Although being intermarried, he helped the Jewish community in many ways. One can even say that he is a model for our time, in showing that one can love the Jewish people and sacrifice for them, even after having intermarried. Here is a song written in honor of Cremieux by the noted R. Aaron Fuld of Frankfurt, author of Beit Aharon. It is taken from Judaica Jerusalem auction cataloge of Summer 1997, p. 6.

Worse than intermarriage is apostasy, but the same issue came up there also. The apostate Daniel Chwolson staunchly defended his former religion and people. How were the Jews to relate to him? Let me quote Louis Jacobs, The Jewish Religion (Oxford, 1995) pp. 99-100:

When Chwolson celebrated his seventieth birthday, a number of Russian rabbis, in gratitude for his efforts on behalf of the Jewish community, sent him a telegram to wish him many happy returns. Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik was more typical of the standard Jewish abhorrence of apostasy when he refused to participate, saying: ‘I do not send congratulatory telegrams to a meshumad.” The wry remark attributed to Chwolson himself in the following story is probably apocryphal. Chwolson is reported to have said that he became a Christian out of conviction. “Who are you kidding?” said a Jewish friend. “How can you of all people, a learned Jew, be convinced that Christianity is true and Judaism false?” To which Chwolson is supposed to have replied: “I was convinced that it is better to be a professor at the university than to be a Hebrew teacher [melamed] in a small town.”

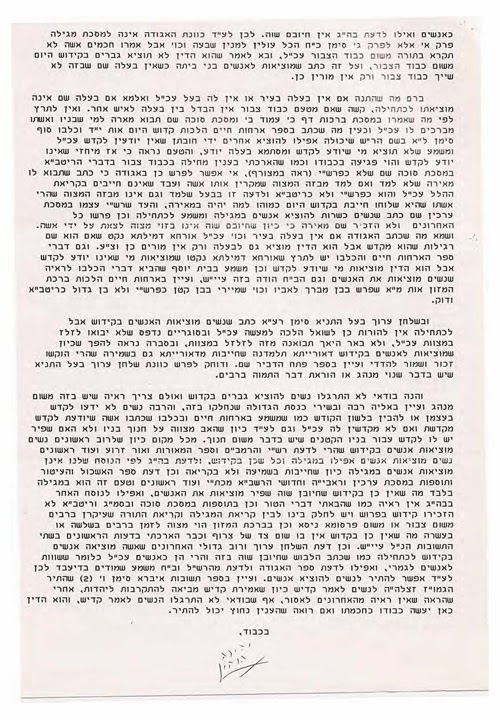

2. I have seen ads for the soon to be published new RCA Artscroll siddur. It will be interesting to see how the battle shapes up between the Sacks siddur and the new RCA Artscroll. I can’t see how the Sacks siddur is going to make any real headway, as I don’t think many shuls are going to get rid of the Artscroll siddur they have been using for so long, and which does just about everything you need a siddur to do. While the new RCA siddur was in the production stages, R. Asher Lopatin of Chicago sent the following letter to the Siddur Committee. I think it is interesting in that it shows some of the concerns of those on the Orthodox left. Although I haven’t seen the new siddur yet, I don’t think I am going out on too much of a limb to predict that the RCA will not be adopting Lopatin’s proposal. (I thank R. Lopatin for allowing me to publish his letter.

[23])

The Practice of Saying She’asani Yisrael for the Birchot HaShachar instead of the three “Shelo Asani”s

In Masechet Menachot, 43b (Bavli), Rabbi Meir says that a person, “Adam”, has to (chayav) say three blessings every day: She’asani Yisrael, Shelo Asani Isha and Shelo Asani Bur. There is a note there that it should be Rabbi Yehuda saying this instead of Rabbi Meir, and also on the next line Rav Acha Bar Ya’akov replaces “Shelo Asani Bur” with “Shelo Asani Aved”.

The G’mara questions why we need to say both Shelo Asani Aved and Shelo Asani Isha, but it gives an answer to this question. Rashi, in his second explanation of that answer, on Menachot 44a, says that we need to say both in order to come up with 100 b’rachot. The Bach (O.C 46) argues that the main reason for saying all three is to increase the number of b’rachot we say to 100. He argues that that is the main reason for saying three b’rachot in the negative (shelo asani) instead of one b’racha in the positive (she’asani Yisrael) – basically, if you would say “She’asani Yisrael” then you couldn’t say “Shelo asani aved, isha”. The Aruch HaShulchan (46, yud) paskins as well that if you say She’asani Yisrael, you cannot say the other two negative b’rachot. The Mishna B’rura (46,16) leaves it as a dispute.

Most Rishonim, notably the Rif and the Rambam (according to the G’ra), disagree with our existing girsa of the words of Rabbi Meir/Rabbi Yehuda, and they have the first b’racha in the negative as “Shelo Asani Goy”. This is the standard version in siddurim, nusach Ashkenaz and Sepharad and Edot Hamizrach, with the occasional nusach of “Shelo Asani Nochri” instead of “goy”. The Magen Avraham (O.C. 46, tet) mentions, that there were siddurim – perhaps many of them – that had the b’racha of she’asani Yehudi , but that that is a mistake of the printers, and the Mishna B’rura (46, 15) says that there are several siddurim with “She’asani Yisrael” but that one should not say that as it is also a mistake that of the printers (shibush had’fus).

The Magen Avraham (O.C. 46, yud) and the Haghot Ha’Gra (O.C. 46) interpret the Rama (46, 4) as suggesting that converts should say “She’asani Ger” and the Bach (46) interprets the Rama as suggesting that converts say “She’asani Yehudi” – instead of the negative.

Moreover, the Rosh is in the back of Masechet B’rachot, paragraph #24 (daf 39 in our versions, referring to B’rachot 60a) – upholds the Girsa that we have in Menachot. It’s in rounded brackets in the Rosh, and the Divrei Chamudot on the Rosh doesn’t like it, but it is there. Importantly, the G’ra affirms it is the girsa of the Rosh (and the Tur, which doesn’t appear in our versions) in his Biur HaGra on OH 46:4.

Therefore:

Since many of the Nosei Keilim and the Aruch HaShulchan feel compelled to ask: Why are these b’rachot in the negative (see Taz 46:4 “Rabim makshim…”)?

And since the girsa that we have in our G’marras is She’asani Yisrael, supported by the Rosh and the G’ra

And since even though the Shulchan Aruch rejects our positive girsa of the b’racha, the Rama does support it (in some version) as a legitimate b’racha in certain circumstances – for a convert

And since even those who reject “She’asani Yisrael/Yehudi/Ger” for a convert, (Sh’lah and Bach, see Taz 46, 10), do not reject it because it is not a legitimate nusach, but, rather, because it does not apply to a convert who has made himself a Jew, rather than being created by God as a Jew.

And since the negativity of the three b’rachot causes lots of misunderstandings in shul where many people come from Reform, Conservative or unaffiliated backgrounds – or even from Orthodox backgrounds without perhaps truly understanding the love that Chazal had for all human beings, male, female, Jewish or Gentile

I have asked my shul, Anshe Sholom B’nai Israel Congregation, a shul that does a lot of kiruv, to follow the girsa of the b’racha according to the G’ra and the Rosh, and say, “She’asani Yisrael” and that a woman say “She’asani Yisraelit” instead of “Shelo Asani Goy.”

Once the first b’racha is said in this way, the way it appears in the G’marra Menachot, then we have no choice, based on the rule of ‘safek b’rachot lekula’ and based on the p’sak of the Aruch HaShulchan (from the Bach) , to avoid saying the final two, negative b’rachot of “Shelo Asani Aved” and “Shelo Asani Isha”.

Clearly this helps avoid many of the questions that people ask about the negativity toward “goyim” or “women” that someone who does not understand Chazal do ask. The answers given help, but for a shul dedicated to kiruv, these b’rachot are a big turn off.

On the other hand, the b’racha of “she’asani Yisrael/Yisraelit” is a beautiful b’racha, thanking God for making me Jewish – proud to be Jewish, excited to begin the day as a Yisrael.

In addition, from a philosophical point of view, rather than beginning the day with negative b’rachot, which accentuate the G’mara of “noach lo la’adam shelo nivra” (see Bach 46, then Taz 46, 4), let us begin the day with a positive b’racha “k’mo sha’ar b’rachot shemevarchim al hatova” (Magen Avraham, 46, 9). Not negating the p’sak of “noach lo…”, but just respecting the positive aspects which G’mara Menachot the way we have it preferred.

Homiletically, “She’asani Yisrael” matches very well with B’reishit 32:27: “Vayomer, Shalcheni ki alah hashacher” – see Rashi ad loc where that is referring to Birchot HaShachar of the angels! And then two p’sukim later, what b’racha (“ki im beirachtani”) does Ya’akov get? “Lo Ya’akov ye’ameir shimcha, ki im Yisrael”! There is no better way to bringing these p’sukim to life than by saying birchot hashachar every day the way our G’marra has it: “She’asani Yisrael” – proud as Ya’akov was to receive the name, “Yisrael.”

Finally, Rav Benny Lau, an important Talmid Chacham and leader of Beit Morasha, has told me that he, too, follows this practice of saying “She’asani Yisrael” – and he tells his daughters to say “Yisraelit” – in the morning and having it replace the three negative b’rachot.

At the same time, it is important to emphasize the need to reach 100 b’rachot a day, and to push people to be careful about saying Asher Yatzar when leaving the bathroom, and b’rachot before and after eating, and being in shul as frequently as possible in order to hear chazarat haShatz to more easily reach 100 b’rachot.

I would humbly ask the Committee responsible for the new RCA Artscroll siddur to consider either putting this practice in the siddur itself, as a possible “hanhaga”, or allowing this way of saying birchot Hashachar to appear on the RCA Artscroll siddur web site, to that I can download it and print it up for my shul, and any other shuls interested in this hanhaga can do the same.

Sincerely yours and with wishes of hatzlacha rabba,

Rabbi Asher Lopatin

3. Virtually every one of our sages, together with all their brilliance, offer at least one an unusual, sometimes even incomprehensible, idea. Since I am writing this right before Sukkot, here is something to think about when you take the Arba’ah Minim. R. Jacob Ettlinger, the greatest of nineteenth-century German gedolim, writes as follows in his Bikurei Yaakov 651:13. (If you raised this safek in shiur today, the rebbe would think you were joking, but as with even the strangest suggestions, one can often find a true gadol who discusses the issue.)

נסתפקתי אם אנו יושבי אירופא יוצאין בד’ מינין שגדלו באיי אמעריקא ואויסטראליען שיושבין לצדינו ותחתינו, וכן איפכא. שידוע מה שכתבו הטבעים שרגליהם נגד רגלינו, ומה שאין נופלין נגד השמים הוא מפני ששם הבורא כח מושך בארץ. וא”כ המינים שגדלו שם אם נוטלין אצלנו הוא הפוך מדרך גדולתן, שאצלנו גדלו ראשי הלולב וההדס ההם יותר למטה מזנבם. או אי נימא, כיון שנוטל הגדל סמוך לארץ למטה זה מקרי דרך גדילתו, והכי מסתברא.

4. In the latest Hakirah (Summer 2009), p. 134 n. 189, Chaim Landerer quotes my translation of a comment by R. Solomon Judah Rapoport. I didn’t know that Landerer was going to publish my translation, and I answered his e-mail quickly and carelessly. The correct translation is not that Rapoport is “as Catholic as the Pope,” but something even stronger. Frankel says that Shir is “more Catholic than the Pope.” (Thanks to R. Ysoscher Katz who caught the error and alerted me. Also thanks to Rabbi Jonah Sievers who is always helpful in matters concerning German translation. Not being a native speaker, and obviously not familiar with all idioms of the language, every translation I have published has been carefully reviewed by expert translators.)

Speaking of errors, let me also correct something that appears in Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy. This correction has already been taken care of in the more recent editions of the book, but those who have the first or second printing can insert the correction into the volume. How this error came about, I have no idea. I must have been in a daze, and it was only when the book was published that I saw it. On p. 180, beginning line 3 from the top, it states “Might one then be able to say that our great divine Torah cannot endure the conjunction of Torah with so-called secular studies . . .” It should be corrected to say, “Might one then be able to say that our great divine Torah cannot compete with so called secular studies . . .”

There is a popular expression

כשם שאין תבן בלא בר כך אין ספר ללא טעויות.

The internet is so amazing as it allows all of us to correct errors that have appeared in our works, and publicize them, something that was not possible in earlier years. R. Judah Ibn Tibbon wrote to his son, R. Samuel (Iggeret ha-Musar, ed. Korah [Kiryat Sefer, 2007], p. 45):

והטעות שתצא מיד האדם הוא הנתפש עליה ונזכר בה כל ימיו.

In other words, unlike a verbal error which is forgotten, something in print is there forever. Yet today, we can minimize this problem by means of the internet. Rather than be embarrassed by errors we have made, and try to ensure that no one learns of them, we should all welcome the opportunity to point out our errors, so that our works are as perfect as we can make them. This is quite apart from the unseemliness of pointing out the errors of others, but not being prepared to call attention to our own mistakes.

Incidentally, Ibn Tibbon’s work is full of important lessons, but he says one thing that is very problematic. On p. 42 he writes:

.

.ואל תתעקש אתה להחזיק בדעתך אפילו אם תדע שהאמת אתך

What sense does this make? Doesn’t the Torah tell us לא תגורו? Didn’t the Rambam speak his mind no matter who disagreed? In our own day, isn’t R. Ovadiah Yosef fearless in expressing his opinion, no matter how much he is attacked? I posed this question to R. Meir Mazuz and he replied:

זו הערה נכונה. כנראה ר’ שמואל היה עוד רך בשנים וחשש האב שיגרום לו קנאה ושנאה כמו שקרה לר”ש בן גבירול, וגם להגר”ע יוסף שליט”א בבחרותו כשחלק על הבא”ח כידוע. אבל כשאדם כותב ספר חייב לגלות את דעתו (בעדינות ובזהירות) ולא יכוף על האמת פסכתר. ובמשך הזמן תתגלה האמת, כי היא לעולם עומדת.

5. I want to call everyone’s attention to a fascinating new book.

Dirshuni, edited by Tamar Biala and Nechamah Weingarten-Mintz, is a book of modern midrashim, written by women. It has been selling very well in Israel and is an exciting genre that deserves its own discussion. Those who want to see some small excerpts can go

here.

To order the book you can go

here6. In my last post I mentioned R. Meir Amsel and the memorial volume that recently appeared. I should have also mentioned that his son, R. Eli Amsel, runs the site

Virtual Judaica.

7. Finally, I thank everyone who commented and e-mailed me about R. Yerucham Gorelik. There is no question that he was a fascinating man, and an entire post could be devoted to the great stories told about him. It is also true that his relationship with YU was complicated. Let me quote what Dr. Norman Lamm wrote about Gorelik, shortly after his death.

Rabbi Yerucham Gorelick appeared at times to be engaged in some kind of titanic inner struggle. He was a cauldron of activity and movement, of perpetual motion. He was a man of striking, sometimes startling contradictions. He appeared to be moving in different directions simultaneously. He was a man of changing moods, of profound dialectical tensions, although he was at all times an ish ha-emet, a man of unshakeable integrity.

For Dr. Lamm’s article, see

here

Notes

[1] “The Emergence of the Provencal Kabbalah : Rabbi Isaac the Blind’s Commentary on Sefer

Yezirah” (1994).

[2] Letter to Samuel Atlas, dated Oct. 16, 1959, published in “Scholars and Friends: Rabbi Jehiel Jacob Weinberg and Professor Samuel Atlas,”

Torah u-Madda Journal 7 (1997), p. 113.

[3] See R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg’s letter to R. Kook,

Iggerot la-Reiyah (Jerusalem, 1990), p. 128

כבר הונח לי בהשתדלותו של רב אחד מרבני העדה הליברלית (דווקא ע”י רב ליברלי של העדה הליברלית, כאלו רוצה הקב”ה לזכות את כל ישראל במעלות שונות שיש בזה מה שאין וכו’).

[4] “The Religious Ethics of Samuel David Luzzatto” (Brandeis University, 1993).

[5] “An Orthodox Embrace of Gentiles? Interfaith Tolerance in the Thought of S. D. Luzzatto and E. Benamozegh,”

Modern Judaism 18 (May 1998), pp. 173-195.

[6] See

here A few days before his death, Rabbi Meir Kahane spoke at Brandeis. I think it was actually his last public talk before the night he was killed. For a video of Gopin confronting Kahane see

here at 24:20, 31:50, and 43:05, and 56. Gopin starts to speak extensively at 1:02:45. The man standing next to Gopin is Dr. Aryeh Cohen, who also briefly served as Orthodox advisor at Brandeis. He now teaches at the American Jewish University. See

here.

[7] See

Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 199:6-7.

[8] He also had a nice sense of humor. On the first day of class he would come in and write his name on the board as “F-x.”

[9] The letter is found in the Chaim Bloch Collection, AR 7155.

[11] Bernstein is now a nationally known professor of law. See

here.

[12] Crown Heights: Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Riot (Waltham, 2006).

[13] I have given the information on this to Rabbi Mark Dratch for his paper at the Orthodox Forum on the topic.

[14] See his article in the

Jewish Chronicle, June 26, 1914.

[15] See Moshe Gresser,

Dual Allegiance: Freud as a Modern Jew (Albany, 1994), p. 73. Hakham Bernays’ grandaughter, Martha (daughter of Berman Bernays) married Sigmund Freud. After they were married, Freud refused to allow her to light Shabbat candles. See ibid., p. 67.

[16] For details on the controversy surrounding Falkenfeld’s selection as rabbi, and how his opponents regarded as an “uncouth Polack” see Heinrich Graetz,

History of the Jews (Philadelphia, 1898), pp. 2-3. When he was rav in Tarnopol, he also had to contend with troublemakers. See R. Solomon Judah Rapoport’s letter in Leopold Greenwald,

Toldot Mishpahat Rosenthal (Budapest, 1920), p. 76. For a picture of his tombstone, see

here.

I can’t explain why on the tombstone he is referred to as “Moses Samuel,” when it should be Samuel ben Moses. For his biography, see Beit Shmuel Aharon al ha-Torah (Jerusalem, 1994), introduction.

[17] See

here. My information on Bilinski’s family background comes from Gotthard Deutsch’s article in the

Jewish Chronicle, June 26, 1914.

[18] The Memoirs of Nahum N. Glatzer (New York, 1997), pp. 126-128. Although Glatzer left Orthodoxy, in his younger years he studied in R. Salomon Breuer’s yeshiva in Frankfurt, and also with R. Nehemiah Nobel. As such, he understood Orthodoxy very well. Glatzer, who died in 1990, was retired when I came to Brandeis in 1985. To my great regret, I never took the trouble to interview him as I did with Prof. Alexander Altmann, who retired from Brandeis in 1976. On pp. 129-130 of Glatzer’s memoir we find the following, which I am sure will interest many readers of the Seforim blog.

In 1944 Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik (called “the Rov” by his followers and admirers) published in Talpiot a major article, “Ish ha-Halakhah” (the Halakhic Personality). The essay, written in a most beautiful Hebrew style, not only claimed for the observance of Jewish law the central place in Jewish life, but denied the—however circumscribed—validity of any other approach. The Halakhah demands a complete control of the Jew, to the exclusion of an emotional state of mind to accompany the halakhc function. There is no rightful place for, or justification of, a state of excitement or religious agitation, say, in the ceremony of blowing the shofar on New Year’s Day; what matters, and matters exclusively, is the proper execution of the ritual.

This exclusion of the emotional side of religion bothered me when I read the essay. I planned a polemic reply but was dissuaded by my colleagues. I happened to visit New York and voiced my feelings to Professor Louis Ginzberg, the great Talmudist. I expected him to agree with me and object to the rigid stand of the Rov. The cautious Ginzberg did not wish to commit himself, or to say something that could be quoted as a criticism of his Talmudic colleague. He, therefore, did not go beyond saying: “I like my whiskey straight,” which was a mild complaint against the Rov’s combination of Halakhah and philosophy. The only reference that could be interepreted as an admission of esthetics into the realm of religion was Ginzberg’s telling of the Gaon of Vilna (brother of Rabbi Abraham, Ginzberg’s forebear in the seventh generation), who near death admired the beauty of the etrog that was brought to him, since the day was one of the Sukkot festival days.

(The Rov, apparently, would have felt: Never mind the etrog’s beauty. What matters is that the citron is without blemish and the benediction is properly pronounced.).

I was disappointed that Ginzberg did not wish to take seriously the younger man’s question. In the meantime, the Rov changed his position and realized the wider dimension of faith. If you wait long enough . . . [ellipsis in original]. Yet, even with the changed position on the part of the Rov, Ginzberg, were he alive, would insist on having his whiskey straight.

Glatzer sees “The Lonely Man of Faith” as expressing a change in the Rav’s earlier “halakho-centrism.” I wonder if Prof. Lawrence Kaplan will agree.

[19] Reshut ha-Yahid (Petah Tivah, 2003), p. 186.

[20] Ma’ayan Omer (Jerusalem, 2007), vol. 1, pp. 186, 194, 205. R. Hillel Posek,

Divrei Hillel, Orah Hayyim, no. 8, strongly supports giving an intermarried man an aliyah, but not as one of the first seven. To deny such an aliyah woould be to embarrass the man, and Posek explains why even sinners cannot be treated with disrespect. See also his comments in

Ha-Posek, Sivan 5747, p. 1336. In Amsterdam the practice was also not to give an intermarried man one of the first seven aliyot. See R. Jacob Zvi Katz,

Leket ha-Kemah he-Hadash (London, n.d.), vol. 3, p. 63.

[21] Sha’alu le-Varukh, vol. 1, no. 40.

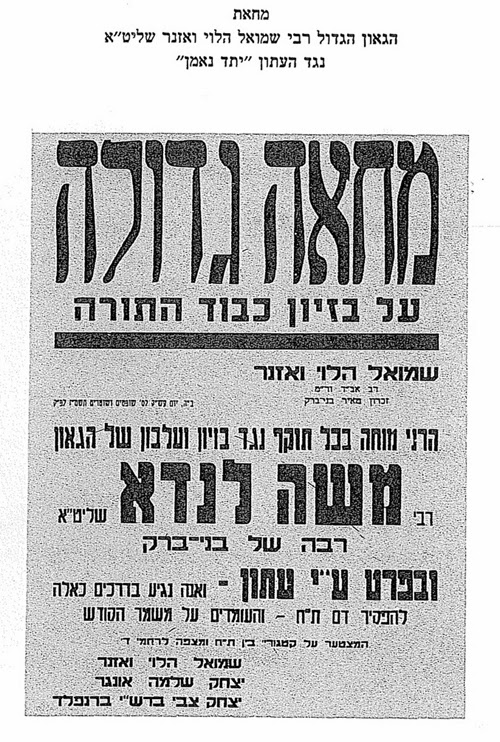

[22] Of course, there are many other poskim who forbid giving an intermarried man an aliyah. Even as liberal a posek as R. Ben Zion Uziel was adamant that you cannot call an intermarried man up to the Torah. See

Mishpetei Uziel, vol 8, no. 53.

[23] For those who don’t know, Lopatin was the first Rhodes Scholar to become an Orthodox rabbi. In fact, he might be the first Rhodes Scholar to become a rabbi in any denomination. R. Chaim Strauchler of Toronto is the second Rhodes Scholar-Orthodox rabbi.