R. Kook on Sacrifices and Other Assorted Comments

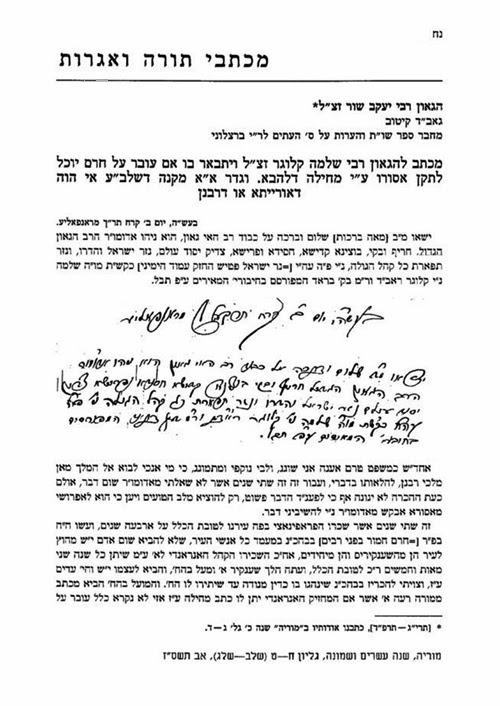

by: Marc B. Shapiro

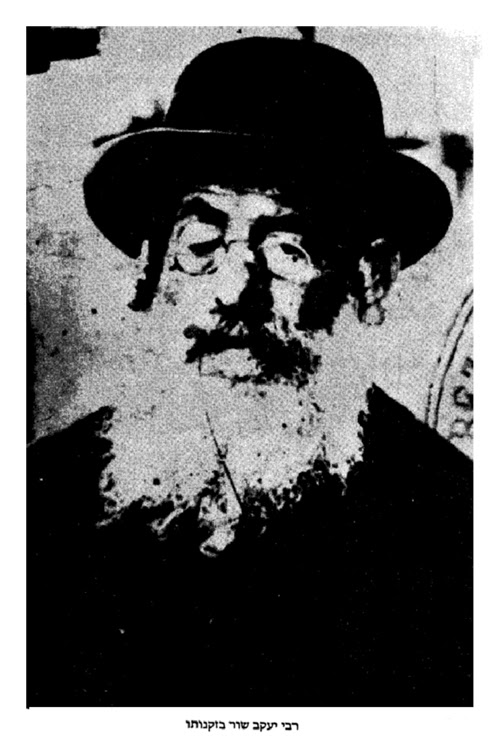

1. At the beginning of my previous post (the Gurock review) I mentioned R. Solomon Isaac Scheinfeld (1860-1943). The source of the comment I quote is his

Olam ha-Sheker (Milwaukee, 1936), p. 77.

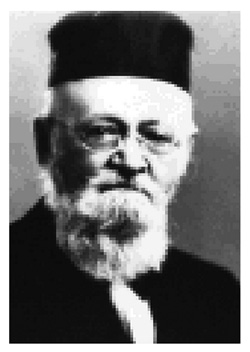

1 Scheinfeld was the unofficial chief rabbi in Milwaukee, arriving there in 1902 and serving until his death in 1943. Here is his picture.

He had a traditional education, having studied for three years in the Kovno Kollel under R. Isaac Elhanan Spektor, from whom he received semikhah.

2 He also had a very original mind, and wrote a number of books and essays. One of his most fascinating works is the article he published under the pseudonym Even Shayish. In this article he argued that since sacrifices will never be revived, they are now irrelevant to Judaism and all references to them should be removed from the prayer book.

R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg has a lengthy essay in which he critiques Scheinfeld’s position. A Hebrew translation of this essay appears in volume 2 of Kitvei R. Weinberg. Yet Weinberg himself leaves open the possibility that there won’t be a return to sacrifices (p. 255):

אין דנים כאן על עצם הרעיון היסודי של הקרבנות. לו היתה היום קיימת אצלנו שאלה כזאת והיא דורשת פתרון דחוף – אין מספר מצומצם של יהודים בארץ אחת בני סמכות להכריע בענין זה, וכל שכן כאשר הם אינם מייצגים את כלל ישראל. שאלה זאת חייבים להביא לפני הבית דין של כלל ישראל. רק לבית דין כזה הרשות לקבוע אם להשאיר טקס מקודש בעם בתוקפו או לבטלו. היום שאין לנו ארץ ולא בית המקדש ולא כהנים הרי זה מגוחך ומצער כאחת להעלות תביעה לבטל עבודת קרבנות!

Weinberg doesn’t mention Maimonides, but this is usually to where people turn when seeking to argue against a revival of sacrifices. According to the Guide 3:32, Maimonides thought that sacrifices were a concession to the masses’ primitive religious notions, developed in an idolatrous society. While Maimonides is explicit in the Mishneh Torah that there will be a return of the sacrificial order, his reason for sacrifices offered in the Guide led some people to assume that his true opinion was that there will not be sacrifices in the future. One example is R. Simhah Paltrovitch, Simhat Avot (New York, 1917), pp. 7-8, who offers a mystical approach:

אמנם מה נעשה במה שדברי מורנו ורבנו הרמב”ם ז”ל שהוא בסברתו מתנגד לאלה הדברים, ואומר כי בימים הבאים עת קץ משיחנו, יבוטל עבודה בקרבנות ולא יהיה עוד . . . להעולם הזה נתנו הפשט והדרוש, ובעולם השני יקויים הרמז והסוד . . .וכן ממש הוא טעם של הרמב”ם ז”ל שיבוטל הקרבנות, כי אז יהי’ התורה על צד הרמז וסוד כמו שארי המצוות המבוארות בתורה, כי יתחלפון מן הפשט לרמז וסוד שמשונים מן הפשט.

R. Joseph Messas also cites Maimonides’ reason for sacrifices and concludes that there will be no return of the sacrificial order (Otzar ha-Mikhtavim, vol. 2, no. 1305).

לפי”ז יתבטלו לעתיד כל הקרבנות כי זה אלפי שנים משנעקרה ע”ז מישראל, וישראל גוי אחד, עובדים רק לאל אחד ועל ידי ישראל בגלותם נעקרה ע”ז גם מכל האומות.

What about the problem that the abolition of sacrifices would mean a change in Torah law, which is a point that R. Kook will also deal with? Messas answers simply:

ואין בזה שנוי בתורה חלילה, דזיל בתר טעמא

What this means, I think, is that from the beginning sacrifices were only intended to be offered in a society in which people were attached to primitive religious notions associated with idolatry, and the animal sacrifices that went along with this. However, once this era has passed from the scene, then there will no longer be any obligation for sacrifices.

A really shocking comment against sacrfices appears in a supposed letter from R. Yaakov of Lissa to R. Zvi Hirsch Kalischer (published in Ha-Posek, Kislev 5712). Responding to Kalischer’s advocacy of renewing sacrifices even before the coming of the Messiah, R. Yaakov claims that to do so would cause Jews to be a subject of mockery by the Gentiles and the non-religious Jews.

לבי נוקף ונפשי מלא רטט ורעד כי אם ישמעו הגויים והקלים בישראל שאנחנו מקריבים קרבנות ימלאו שחוק פיהם ונהיה

ח”ו ללעג ולקלס וה’ יודע כמה צרות וקלקולים יצמחו מזה

It is very unlikely, to put it mildly, that a gadol be-Yisrael would give this as his reason for not fulfilling a mitzvah. When one realizes that the person who published this letter was the famous forger Chaim Bloch, then all doubts are removed: The letter, like so much else published by Bloch, is a complete forgery. Apparently Bloch had some negative feelings about sacrifices and transferred them to R. Yaakov. Interestingly, when this letter was republished in Dovev Siftei Yeshenim, vol. 1, Bloch made a subtle change in the letter, which as far as I know, no one has yet pointed out. The letter’s authenticity had been attacked by Zvi Harkavy in Kol Torah (Nisan-Iyar 5712), and one of the things he pointed to was this line, and that R. Yaakov could never have written it. So when Bloch republished the letter, in an attempt to bolster its authenticity, he altered it to read as follows (I have underlined the newly added words):

כי אם ישמעו הגויים והקלים בישראל שאנחנו מקריבים קרבנות בזמן הזה לפני ביאת משיח צדקנו ובטרם עומד בית מקדשנו

על מכונו, ימלאו שחוק פיהם ונהיה ח”ו ללעג ולקלס

Had he been smart enough to have added these extra words in the first edition of his forgery, it would have been more believable. Now R. Yaakov is not speaking of the non-Jews and the non-religious mocking the offering of sacrifices, but only mocking the offering of them before the coming of the Messiah and the building of the Temple.

Michael Friedlaender’s

The Jewish Religion (London, 1891), was for many years regarded as a standard work of Orthodox belief. As far as I know, it was the first of its kind in English and can still hold its own against many more recently published books. You can see it

here. On pages 162-163, 417-418, he speaks of the return of the sacrificial order in Messianic days, and how we should look forward to this, even if it is contrary to our taste. He says that we should not model Divine Law according to our liking, but rather model our liking according to the will of God. Yet despite these strong statements, he was also sensitive to those who were not comfortable with sacrifices. He writes as follows (p. 452):

References to the Sacrificial Service, and especially prayers for its restoration, are disliked by some, who think such restoration undesirable. Let no one pray for a thing against his will; let him whose heart is not with his fellow-worshippers in any of their supplications silently substitute his own prayers for them; but let him not interfere with the devotion of those to whom “the statues of the Lord are right, rejoicing the heart” . . . and who yearn for the opportunity of fulfilling Divine commandments which they cannot observe at present.

This passage is quoted by British Chief Rabbi Joseph Hertz in his Authorised Daily Prayer Book, p. 532. Upon seeing this, R. Yerucham Leiner, then living in London, wrote a letter to the Jewish Chronicle (Dec. 17, 1943; I learnt of this from Louis Jacobs, Tree of Life, second ed., p. xxix). Before quoting from his letter, let me reproduce what Wikipedia says about this most incredible figure.

Grand Rabbi Yerucham Leiner of Radzin, son of Likutei Divrei Torah, author of Tiferes Yerucham, Zikaron LaRishonim, Mipi Hashmua, Zohar HaRakiya. Moved from Chelm to London to America. Continuation of the Radziner line in America, and one of the last direct descendants of the Leiner family. After the war, he did not reinstitute the wearing of techeiles as other branches of Radzin did, even though his father, Grand Rabbi Avraham Yehoshua Heschel Leiner of Radzin-Chelm, wore them, as he was a chosid of his older brother, the Orchos Chayim, who had reinstituted the wearing of techeiles. Reb Yerucham believed that the original formula of his uncle was lost during the war. This is the reason that his family doesn’t wear techeiles today, only pairs that were left from pre-war Europe. Reb Yerucham was an expert in all areas of Torah and scholarship. There existed very few admorim/tzaddikim since the beginning of Chassidus who were also lamdanim in both the Polish and Lithuanian styles of learning, bibliographers, Jewish historians, very learned in Kabbalah works, philologists, and masters of both the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds. Reb Yerucham was very close with the Satmar Rebbe, Rabbi Yoelish Teitelbaum ZTVK”L. He always made sure to spend a few weeks vacationing with the him, specifically learning Midrashei Chazal, of which they were both masters. He studied and visited with Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner, and they were good friends in later life. They always treated one another with special respect. He established the Radziner shtiebel in Boro Park. Died 20 Av 5724 (1964). Buried in Beth Israel Cemetery, Woodbridge, New Jersey

Responding to the quote from Friedlaender, Leiner wrote: “This opinion was put forward by the founders of Reform Judaism, Holdheim and Geiger. But it is hardly in accord with Orthodox traditions of Judaism.” The editor of the Jewish Chronicle responsed: “The words quoted with regard to the Musaph are those of the great and sainted scholar, Dr. Michael Friedlander, for 42 years Principal of Jews College: and it is certainly strange to class him with Holdheim and Geiger.”

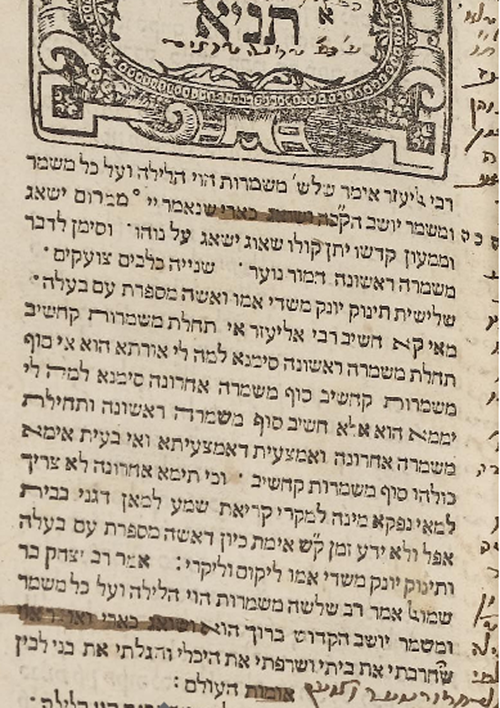

The most famous of our sages to speak of a Messianic era without animal sacrifices is, of course, R. Kook, who envisions vegetable sacrifices. He writes this in his commentary to the siddur,

Olat ha-Reiyah, vol. 1, p. 292. In the preface R. Zvi Yehudah tells us that he began writing this commentary during World War I. I don’t need to go into any detail on this, as I have done so already in

The Limits of Orthodox Theology, where I also mention passages in R. Kook’s writings that offer a different approach. The notion that there will only be vegetable sacrifices in Messianic days is, of course, a radical position, and many who don’t know R. Kook’s writings find it impossible to accept that he could have said this. This is what happened when R. Yosef Kanefsky of Los Angeles published an essay in which he mentioned R. Kook’s view.

3 He was attacked by some prominent rabbis since they found it impossible to believe that R. Kook could say what was attributed to him. Yet it was Kanefsky who was right, not his opponents.

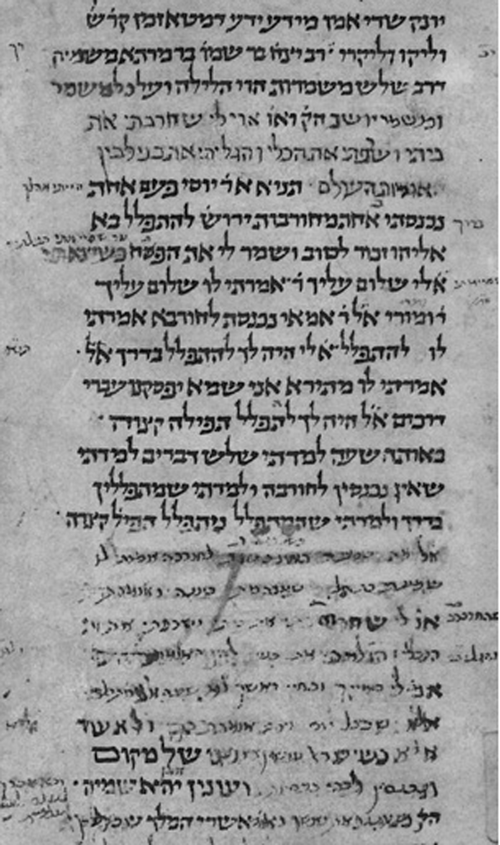

In my book I dealt with R. Kook’s position on sacrifices, because positing that there will be no sacrifices in the future would seem to be in contradiction to Maimonides’ Principle that the commandments of the Torah are eternal. That consideration is precisely what makes his position so radical. A couple of years ago one of R. Kook’s notebooks dating from his time as rabbi in Bausk, which lasted until 1904, was published. We actually have two publications of this, one by Boaz Ofen called Kevatzim mi-Ketav Yad Kodsho, vol. 2 (Jerusalem, 2008), and the other, which comes out of the world of Merkaz ha-Rav, called Pinkesei ha-Reiyah (Jerusalem, 2008).

This is not the first competing publications of the same material by these people, and as I will show in my forthcoming book, the Merkaz editions are tainted by censorship in that “problematic” passages are removed.

4 Those who claim to be the greatest adherents of R. Kook have once again taken it upon themselves to save their master from himself, as it were, and decided which writings of R. Kook should appear and which should not. Yet in the passage I am interested in now (no. 8 in the Ofen edition and no. 6 in the Merkaz edition), the two books are identical. The passage is very significant since it shows you that even in his earlier years R. Kook had the same notion later expressed in

Olat ha-Reiyah, that the future would only know vegetable sacrifices. (In case people are wondering, R. Kook was

not a vegetarian. Yet he did see vegetarianism as part of the eschatological future. His great student, the Nazir, was a vegetarian, as was Nazir’s son-in-law, R. Shlomo Goren, and as is his son, R. Shear Yashuv Cohen.

5)

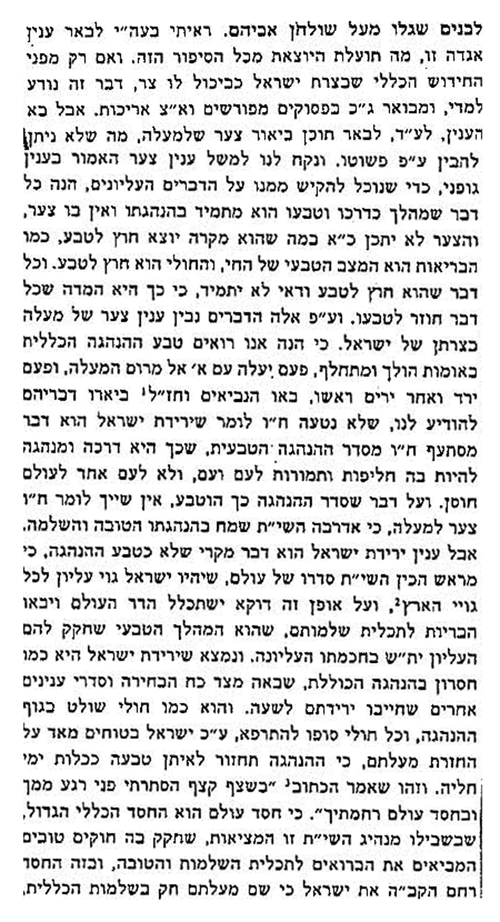

This passage gives us new insight into R. Kook’s view of sacrifices, and how things will change in the future era. He begins by speaking of the abandonment of meat-eating in the Messianic era, since this will not be something that people desire. Recall that in speaking of eating meat, the Torah writes (Deut. 12:6): כי תאוה נפשך לאכל בשר, which means “when thy soul desires to eat meat.” The Messianic era is not a time when people will have this desire, as R. Kook also explains in his famous essay on vegetarianism, “Afikim ba-Negev”.

What about the sacrifices that are required by the Torah? R. Kook offers a few possibilities. One is that sacrifices will still be necessary. Yet he also speculates that perhaps certain animals will be so spiritually advanced that they will on their own offer themselves as sacrifices, in acknowledgment of the great benefit that will come to them and the world through their actions.

6 This solves the problem of people deliberately killing animals, which goes against his conception of the eschaton.

What is most interesting for our purpose is another suggestion by R. Kook, namely, that the Sanhedrin will use its power to uproot a matter from the Torah in order to abolish obligatory animal sacrifices. Their reason for doing this will be that the killing of animals will no longer be part of the culture in Messianic days. R. Kook even shows how the Rabbis will be able to find support for this step from the Torah. What he is doing, I think, is imagining himself as part of the future Sanhedrin that abolishes sacrifices, and informing us of the derashah that will be used to support this. This is related to what I wrote in an earlier post, see

here, and I repeat it now:

As to the general problem of laws that trouble the ethical sense of people, we find that it is R. Kook who takes the bull by the horns and suggests a radical approach. The issue was much more vexing for R. Kook than for other sages, as in these types of matters he could not simply tell people that their consciences were leading them astray and that they should submerge their inherent feelings of right and wrong. It is R. Kook, after all, who famously says that fear of heaven cannot push aside one’s natural morality (Shemonah Kevatzim 1:75):

אסור ליראת שמים שתדחק את המוסר הטבעי של האדם, כי אז אינה עוד יראת שמים טהורה. סימן ליראת שמים טהורה הוא, כשהמוסר הטבעי, הנטוע בטבע הישר של האדם, הולך ועולה על פיה במעלות יותר גבוהות ממה שהוא עומד מבלעדיה. אבל אם תצוייר יראת שמים בתכונה כזאת, שבלא השפעתה על החיים היו החיים יותר נוטים לפעול טוב, ולהוציא אל הפועל דברים מועילים לפרט ולכלל, ועל פי השפעתה מתמעט כח הפועל ההוא, יראת שמים כזאת היא יראה פסולה.

These are incredible words. R. Kook was also “confident that if a particular moral intuition reflecting the divine will achieves widespread popularity, it will no doubt enable the halakhic authorities to find genuine textual basis for their new understanding.”

R. Kook formulates his idea as follows (

Iggerot ha-Reiyah, vol. 1, p. 103):

ואם תפול שאלה על איזה משפט שבתורה, שלפי מושגי המוסר יהיה נראה שצריך להיות מובן באופן אחר, אז אם באמת ע”פ ב”ד הגדול יוחלט שזה המשפט לא נאמר כ”א באותם התנאים שכבר אינם, ודאי ימצא ע”ז מקור בתורה.

R. Kook is not speaking about apologetics here, but a revealing of Torah truth that was previously hidden. The truth is latent, and with the development of moral ideas, which is driven by God, the new insight in the Torah becomes apparent.

Ad kan leshoni in the previous post.

In other words, R. Kook sees the Sanhedrin as able to actualize new moral and religious insights that have become apparent. That is why it is important for the Sanhedrin to use derashot when dealing with these matters, as this shows that the idea is not something new that has been developed, but something that was latent in the Torah, and only now has become apparent.

So what derashah can be used to justify an abolishment of animal sacrifices? R. Kook points to Num 28:2: את קרבני לחמי לאשי . This is usually translated as “My food which is presented to Me for offerings made by fire”. Yet the word לחמי actually means “my bread.” Right after this, in discussing the particulars of the sacrifice, the Torah states: “The one lamb thou shalt offer in the morning.” R. Kook’s proposed messianic derashah is: “Whenever animals are killed for personal consumption, you should use them for sacrifices, but when they are not killed for personal use, make sacrifices of bread.”

I don’t think I am exaggerating in saying that this is one of the most provocative and radical texts in R. Kook’s writings. I say this not because of his advocacy of abolishing sacrifices, which I don’t think to be that significant in the larger scheme, but due to how he is envisioning the process by which the Rabbis will actually use derashot to create a Messianic Judaism.

The Rambam, Hilkhot Mamrim 2:1, speaks of laws derived from the hermeneutical principles that can be altered by a future beit din ha-gadol (even one not as great as the one that established the original law). This was the great fear of the opponents of a reconstituted Sanhedrin, that the Mizrachi rabbis would take upon themselves to do precisely this. Since so many of our laws are based on derashot, Judaism as we practice it can be entirely reworked. R. Kook is showing us how this can be done, but he is going further than anything Maimonides envisioned, since sacrifices are not matters that have been established based on a rabbinic derashah but are commanded by explicit biblical verses.

Basically, what R. Kook is doing is recreating the world of the Pharisees, before Judaism was bound to codes (beginning with the Mishnah). It was a time when Jewish law was developing and the biblical verses could be read—some would say “read”— in all sorts of ways. In the days of the Pharisees much of the halakhah as we know it was created, and to a large extent that can be done again in the Messianic era.

Here are R. Kook’s words (note also his exegesis with ריח ניחוח) :

שהסנהדרין אז ימצאו לנכון, ע”פ הכח שיש להם לעקור דבר מה”ת בשוא”ת, לפטור מקרבנות החובה של מין החי, כיון שכבר חדלה הריגת החי מן המנהג של תשמישי הרשות והמקרא מסייע, שקרא הכתוב לקרבן לחם, “את קרבני לחמי לאשי”, ואח”כ אומר “את הכבש אחד”, הא כיצד? כל זמן שבע”ח קרבים לתשמיש הרשות, עשה בע”ח לגבוה, אבל כשבע”ח אינם קרבים לרשות, עשה הקרבנות מלחם, ועל זה רמזו חז”ל: “כל הקרבנות בטלין וקרבן תודה אינה בטלה” שיש בה לחם . . . רק כעת עד זמן ההשלמה תאמר להם שיקריבו כבשים, ומותנה תמיד לריח ניחוח, וכיון שיבורר בזמן ההשלמה שהריגת הבע”ח [אינה ראויה] אי אפשר שתהיה לריח ניחוח.

R. Kook then cites the proof he mentions in Olat ha-Reiyah and in his essay “Afikim ba-Negev” (Otzarot ha-Reiyah [Rishon le-Tziyon, 2002], vol. 2, p. 103), that Malachi 3:4 writes: וערבה לה’ מנחת יהודה וירושלים כימי עולם וכשנים קדמוניות . This verse, in speaking of a sacrificial offering in Messianic days, mentions the minhah sacrifice, which is not an animal offering.

As mentioned, the passage from R. Kook is so interesting because it shows that he was not merely thinking about the Messianic era, but also the actual functioning of the future Sanhedrin. He was imagining the derashot that could be used to “update” Judaism. I am unaware if this aspect of R. Kook’s thought was known before the publication of this latest volume. I also don’t know if any scholars have taken note of it even subsequent to the publication. However, in “Afikim ba-Negev” (Otzarot ha-Reiyah, vol. 2, p. 103), R. Kook also, in an offhand sentence, provides a possible derashah to justify the abolishment of sacrifices. He doesn’t develop the idea, but just puts it out there. Here is the sentence:

והגביל “לרצונכם תזבחהו” (ויקרא יט, ה) שיהיה אפשר וראוי לומר “רוצה אני”. (רש”י על ויקרא א, ג).

The Talmud, Rosh ha-Shanah 6a, which is quoted by Rashi, Lev, 1:3, states that one cannot bring a sacrifice unless it arises from one’s free will. Now the Talmud, which is speaking of one particular sacrifice, actually says that we force him to bring it until he agrees, and this means that he is “willing.” But R. Kook is using this passage to hint at a different matter. In future times, when sacrifices will be so far from human sentiment, it will be impossible to do it willingly. The derashah, לרצונכם תזבחהו , will then come into play. Since this teaches that one can only bring a sacrifice when one is willing, at a time when animal sacrifices are not considered acceptable, and thus not something people “want” to do, animal sacrifices will no longer be a requirement. Remember, R. Kook describes this future era as one in which the animals will be far advanced of what they are now. It is only when the animals are at the low state that they currently are, that we can offer them as sacrifices and eat them. He writes (Otzarot ha-Reiyah, vol. 2, p. 101), in a passage in which animals are compared to one’s children:

מי לא יבין שאי אפשר להעלות על הדעת שיקח האדם את בניו, ברוח אשר יטפחם וירבה אותם להיטיב ולהשכיל, ויזבחם וישפך דמם?

The texts we have seen are important in explaining how his viewpoint of the abolishment of sacrifices relates to the Ninth Principle of Maimonides. As mentioned, in my book I listed R. Kook’s view as being in opposition to the Principle. R. Kook is certainly great enough to disagree with Maimonides in this matter had he chosen to. Yet we see from his newly published writings that he would not have regarded himself in disagreement, because he understands the abolishment of sacrifices to be carried out in a purely halakhic fashion. Since the Rabbis have the exegetical authority to do such things, an authority given to them by the Torah, we are not speaking of a revision of Torah law. This case is then no different than any of the other examples where the Sages interpret Torah law different that the peshat of the verse.

Returning to the newly published text, R. Kook’s imagination continues to run, and he doesn’t stop with sacrifices. In my book I called attention to R. Hayyim Halberstam’s view that in Messianic days the first born will take the place of the kohanim. R. Kook must have been attracted to this view for kabbalistic reasons, and here he provides a possible basis for how this too can be justified by the Rabbis. He also notes that since the change can be justified, “it is not uprooting a Torah matter, but rather fulfilling the Torah.”! In other words, built into the Torah is the notion that the kohanim would only be temporarily in charge of the divine worship. R. Kook argues that since the First Born were removed from their role because of the sin of the Golden Calf, it is impossible for the effects of this sin to last forever, as repentance is a more powerful force. Therefore, when the sin of the Golden Calf is atoned for there will no longer any reason for the First Born to be kept from the Avodah, and it will return to them.

Following this, R. Kook offers another way of explaining why his view of sacrifices should not be seen as a “reform” or as evidence of the Torah changing (he obviously was sensitive to this point). He says ויש לדרוש, in other words, he is once again providing the halakhic justification that can be used by a future Sanhedrin in abolishing sacrifices. His new exegetical reasoning goes as follows: The obligation of animal sacrifices was only intended for an era when the kohanim were in charge of the Avodah. This is how one is to understand the verse (Lev. 11:1) ושחט אותו על ירך המזבח . . . וזרקו בני אהרן הכהנים את דמו. In other words, it is only to the descendants of Aaron that animal sacrifice is commanded,

אבל כשיהיו כשרים ג”כ בכורות, אז מטעם העילוי של בע”ח וכלל המציאות אין הבע”ח נהוגים כ”א לחם ומנחה . . . וכך הוא המדה בכל מקום שנמצא פסוק בתורה וסברא ישרה שיש כח ביד ב”ד הגדול, מכש”כ כבצירוף הנביאים לפסוק הוראת גדולות כאלה.

Note that R. Kook ties together a verse in the Torah with logic. When both are present, then the Beit Din ha-Gadol is able to act in order to make adjustments to Torah law. In this matter, the “sevarah yesharah” is the sense that animal sacrifices will not suitable for the future eschatological era, and the verses in the Torah that he cites give “cover” to the sevarah yesharah. That is, they provide the exegetical justification. (I wonder though, is R. Kook really correct when he implies that the only time the Sages could uproot a commandment was when they also had a biblical verse to justify this?)

R. Kook concludes that all that he is speaking about is a long way off, and it is possible that the Resurrection will come before this and then all sorts of things will change. Yet all his prior ruminations here are about a pre-Resurrection era, when the Beit Din ha-Gadol is functioning and adjusting Torah law by means of derashot and sevarah yesharah. This is not the sort of thing that will be taking place post-Resurrection.

7

Finally, lest anyone start using R. Kook’s thoughts in an antinomian fashion, he throws in the following for good measure:

וזה היה מקור תרבות והרע ד”אחר”, שחזי שהמצות יש להן יחש מוגבל ותכליתי, חשב שבאמת אפשר להתעלות למעלה מהמעשים, גם בלא עת, ובאמת הכל אחדות יחיד היה הוה ויהיה, וכל עת וזמן את חובותיה נשמור, בלא נדנוד צל פקפוק.

Earlier in this post, I referred to the implications of R. Kook’s ideas with regard to Jewish law being adjusted because of new moral insights. In fact, I think it is R. Kook who provides the most comprehensive and satisfying approach to this issue. I don’t want to get into that subject at present, as I plan on returning to it, especially as a number of people have written to me about R. Kook’s views. In my future post I will illustrate my point by citing a number of examples of rulings and statements by mainstream halakhists from earlier centuries which could never be made today. The only way to explain this, I will argue, is that there has been a change in societal norms and this has made certain approaches not just practically impossible but simply wrong for our times. (See

here where I cite in this regard R. Weinberg and R. Aviner.) However, I promised someone that I would give one example in this post, so here it is. R. Hayyim Benveniste,

Keneset ha-Gedolah, Even ha-Ezer 154,

Hagahot Beit Yosef no. 59, in discussing when we can force a husband to give a divorce, writes as follows:

ובעל משפט צדק ח”א סי’ נ”ט כתב דאפי’ רודף אחריה בסכין להכותה אין כופין אותו לגרש ואפי’ לו’ לו שחייב להוציא.

Can anyone imagine a posek, from even the most right-wing community, advocating such a viewpoint? I assume the logic behind this position is that even if the man is running after her with the knife, we don’t assume that he will actually kill her. He must just be doing it to scare her, and that is not enough of a reason to force him to divorce her. And if we are wrong, and he really does kill her? I guess the reply would be that this isn’t anything we could have anticipated even if we saw the knife in his hand, sort of like all those who have let pedophiles run loose in the yeshivot, presumably on the assumption that just because a man abused children in the past, that doesn’t mean that he will continue to do so.

8

Notes