Taliban Women and More

Marc B. Shapiro

1. In this post I am going to respond to a number of emails and requests to deal with certain topics. I can’t get to everything I was asked about, and will only touch on some topics, but here is a start.

Let’s begin with the common practice in the Israeli haredi world of ignoring what the Sages tell us in Kiddushin 29a and not teaching young men a trade so that instead they can devote themselves to Torah study.[1] People assume that this is a late twentieth-century phenomenon. While it is true that the numbers of people who currently follow this approach is much larger than ever before in history, it must be noted that even in previous years there were those who acted in the same fashion. We see this from R. Pinhas Horowitz’ strong words against this approach in his Sefer ha-Berit, vol. 2, ma’amar 12, ch. 10.

R. Meir Mazuz has recently suggested that this negative attitude towards work explains a passage in one of the most popular Shabbat zemirot.[2] The following lines appear in Mah Yedidot.

חפציך בו אסורים וגם לחשוב חשבונות, הרהורים מותרים ולשדך הבנות, ותינוק ללמדו ספר למנצח בנגינות

Artscroll, Family Zemiros, translates as follows:

Your mundane affairs are forbidden on it [Shabbat] and also to calculate accounts; Reflections are permitted and to arrange matches for maidens; To arrange for a child to be taught Scripture, to sing a song of praise.

(R. Jonathan Sacks, in his siddur, p. 388, translates the last words similarly: “singing songs of praise.”)

The first thing to note is that the translation is incorrect. The words למנצח בנגינות do not mean “to sing a song of praise”. The word למנצח is not an infinitive (that would be לנצח, patah under the nun). It is a noun with a prefix, and means “to the choirmaster” or something like that. Artscroll, in its Tanach (Ps. 6:1), translates למנצח בנגינות: “For the conductor, with the neginos.” The note tells us that neginos are a type of musical instrument.

I sympathize with Artscroll when confronted with the need to translate the words למנצח בנגינות in the song. It is obvious that the words make no sense. Until then the passage was speaking about what was permitted on the Sabbath and then you have למנצח בנגינות .

This is an old problem and while a couple of forced answers have been suggested, others have argued that what we have here a mistaken reading, and instead of למנצח בנגינות it should read וללמדו אומנות (perhaps even reading אומנות with a final holam in order to make it rhyme). The entire paragraph in Mah Yedidot is derived from Shabbat 150a, and there it states: משדכין על התינוקות ליארס בשבת ועל התינוק ללמדו ספר וללמדו אומנות. After seeing this, can anyone still have a doubt that the standard version is incorrect?

R. Mazuz is apparently unaware that others before him had already suggested that וללמדו אומנות was the original version,[3] but he is the only one to suggest why the text was changed. Although it strikes me as a bit far-fetched, he assumes that when people stopped teaching their sons a trade this verse became problematic, and therefore someone took it upon himself to alter the text.

After criticizing Artscroll’s translation (and in future posts I will have more such examples), let me now mention an instance where of all the translations I have consulted, only Artscroll gets it right.

Every Friday night we say the following (which is based on Isaiah 52:1):

התנערי מעפר קומי לבשי בגדי תפארתך עמי

Sacks translates: “Shake yourself off, arise from the dust! Put on your clothes of glory, My people.” All the translations I have consulted render along these lines. The problem, however, is obvious. If “My people” is being addressed, then why are the verbs and the suffix of תפארתך feminine?

Artscroll recognized the problem and translates: “Shake off the dust – arise! Don your splendid clothes, My people.” The translation is explained in the note: “Jerusalem – your most splendid garment is Israel. Let the redemption come so that they may inhabit you in holiness once more.” In other words, Jerusalem is being addressed, not the people of Israel. “My people” is therefore identified metaphorically with “your splendid clothes.” The stanza thus needs to be read as a continuation of the prior stanza – מקדש מלך עיר מלוכה – which is also addressed to Jerusalem.

Furthermore, if you look at Isaiah 52:1, upon which the text is based, it reads: לבשי בגדי תפארתך ירושלים עיר הקודש “Put on your beautiful garments, O Jerusalem, the holy city.” So we see that also in the original verse it is Jerusalem that is being addressed. Artscroll cites this interpretation in the name of Iyun Tefillah (found in Otzar ha-Tefilot) and refers to it as “novel”. This understanding (which is actually the peshat of the words) was also suggested by R. Kook[4] R. Baruch Epstein,[5] and R. David Hadad.[6]

2. A long time ago I was asked to deal with the so-called Jewish Taliban women, who completely cover their faces when they go out. I know that everyone has downplayed their significance and referred to them as crazy. I think that this is too optimistic an assumption. Although I am not predicting it, I would not be surprised if this turned into a real phenomenon. All these women need is one somewhat respected Torah scholar to support them and they will then become just another faction in extremist Orthodoxy. You will then have groups that don’t allow women to drive (or smoke, or use a cellular phone, etc.), and another group that also requires that they cover their faces when they leave home. The real difference today is that while with the other groups we have men telling women how to behave for reasons of tzeniut, the Taliban group is completely female driven and led.

The truth of the matter is that the Taliban women make a certain amount of sense. They are part of a community that forbids women’s (and even little girl’s) pictures to appear in printed matter because seeing this might arouse sexual thoughts in men.[7] Even though these women never studied Talmud, we know that one doesn’t need to be talmid hakham to derive a basic kal va-homer. Even these uneducated women can conclude that if men’s souls can be destroyed by seeing a picture of a woman or a little girl, how much more so can they be driven to sexual frenzy by seeing a live woman or girl? As such, it makes perfect sense that when they go out on the street they are completely covered and only their husband and children are permitted see their faces.[8] It is their opponents in the haredi word who have to explain why it is permitted to see the faces of real live women but forbidden to see their pictures. It doesn’t make a lot of sense, as the Taliban women have rightly concluded.

I am sure that any rabbinic authorities that come to support the Taliban women will be able to find relevant sources to defend this lifestyle. I know this will surprise readers, especially as many rabbis have declared that the Taliban women are completely distorting Jewish rules of modesty. These rabbis have claimed that unlike Arabs, Jewish women have never dressed this way (unless they were forced to) as the face is not

ervah. Therefore, these rabbis have asserted, Jewish

tzeniut has never,

has ve-shalom, seen it as a value for women to completely cover their faces.

Lines like this are good for applause in a Modern Orthodox (and even a haredi) shul, among people anxious to be reassured that these Taliban women couldn’t possibly have any sources in our tradition for their actions. The truth of the matter is that, whether we like it or not, there are sources that are strong supports for the Taliban women, and there is no reason to deny that they exist.[9] Sotah 10b is clearly praising Tamar when it mentions that she was so modest that she covered her face in her father-in-law’s house. R. Joseph Messas (Mayim Hayyim, vol. 2, Orah Hayyim no. 140) points out that Shabbat 6:6 refers to Arabian Jewish women going out veiled, which means that their entire face was covered except for their eyes. He also points to Shabbat 8:3: כחול כדי לכחול עין אחת, which as explained in the Talmud refers to those women who were so modest that they were completely veiled, with only one eye showing in order for them to see (see Rashi, ad loc. See also Rashi to Isaiah 3:19.) Messas tells us that in his youth he personally saw Jewish women who dressed like this: וכן ראינו בימי נעורנו. R. Meir Mazuz’s mother testified that brides in Djerba would only show one eye, also for reasons of modesty.[10]

Here we have evidence that the Taliban dress was actually a traditional Jewish dress, just the sort of material that can be used to support the new dress code. In fact, one doesn’t even need to look to Morocco or Djerba, or even to talmudic literature, to find sources that women dressed this way. It is found right in the Song of Songs 4:9. This verse states: “Thou has ravished my heart with one of thine eyes.” The Soncino translation explains: “It is customary for an Eastern woman to unveil one of her eyes when addressing someone.” In other words, normally, for reasons of modesty, the woman is entirely covered (although this covering would be see-through so she could walk properly), and only at certain times would she remove it to reveal one eye. I know some people are thinking that this is exactly the sort of explanation you can expect from Soncino, which loves to quote non-Orthodox and even non-Jewish commentators, and if you look at the various traditional commentaries they do indeed provide all sorts of allegorical meanings for this verse. Yet the Jerusalem Talmud, Shabbat 8:3, also understands the verse as giving an example of modest behavior on the part of the woman, that she only uncovers one eye. As explained by Korban ha-Edah:

מביא פסוק זה לראיה שדרך הצנועות לצאת באחת מעיניה מכוסה ואחת מגולה

(Korban ha-Edah and all the other traditional commentaries I have seen assume that the woman always goes with one eye uncovered, while Soncino explains that she only uncovers this one eye on special occasions.)

R. Baruch Epstein takes note of this passage in the Jerusalem Talmud in his commentary to Song of Songs, and adds.

לפנים בעת שהיו נוהגות הנשים ללכת עטופות היו מגלות רק עין אחת כדי לראות מהלכן, ומכאן רמז שמנהג כזה הוא מנהג כשר וצנוע, שהרי כן משבחה הכתוב שלבבתו בעין אחת.

If this practice is, as Epstein says, a מנהג כשר וצנוע, then I don’t think we should be surprised if some circles attempt to bring it back into style.

A few paragraphs above I quoted a responsum of R. Joseph Messas.[11] In this teshuvah he also explains why women can’t be given aliyot. As is well known, in earlier days this was permitted but the Sages later forbid it on account of kevod ha-tzibbur (Megillah 23a). There have been lots of interpretations of what kevod ha-tzibbur means, but Messas has a very original perspective. He claims that the reason women were banned from receiving aliyot is because this would lead to sexual arousal among the male congregants. Messas believes that this came from the actual experience of the Sages, who saw what happened when women received aliyot. He also assumes that these women would have been dressed in a Taliban-like fashion[12]: בהסתר פנים כמנהג נשים קדמוניות. But even such a woman, covered head to toe, still created problems with the sexually fixated men.[13]

ובדורות שאחריהם ראו שיש בזה מחשבת עריות, שהצבור היו שואלים זה לזה, מי זאת עולה . . . ואם היה קולה ערב מוסיף להבעיר אש היצר, ולכן עמדו ובטלו את הדבר.

Knowing how concerned the Sages were about avoiding situations that could lead to sexual thoughts, it makes sense that they would ban the practice if they thought that women’s aliyot would lead in this direction.[14] But Messas now has a problem, because the Talmud doesn’t give this as a reason for abolishing women’s aliyot. Instead, it states that they were abolished because of kevod ha-tzibbur. This leads Messas to offer one of the wonderfully original interpretations that can be found so often in his writings. He claims that because the Sages didn’t want to insult the (male) community by telling them the real reason why they abolished the aliyot, namely, that even during Torah reading men can’t control themselves from sexual thoughts, therefore they invented the concept of kevod ha-tzibbur! However, this is not the real reason, and therefore all attempts to explain the meaning of the term are irrelevant. The real reason is the male sexual desire which as Messas states, is always in need to being fenced in:[15]

וכדי שלא להראות את הצבור שחשדו אותם, תלו הטעם מפני כבוד הציבור, שלא תהא האשה הפטורה מן הדבר מתערבת עם האנשים המחוייבים בו וכן בכל דור היו גודרים גדרים בעריות

Based on this male weakness, Messas claims that the mehitzah has to be built in such a fashion that the men cannot see the women. He even has a most original way to explain to the women why they are placed in what amounts to a completely other room. Rather than being a sign of their insignificance, it is a sign of how important they are. The proof of this importance is that men are constantly drawn to look at them. Therefore, by building a high mehitzah we are able to save the men from themselves.

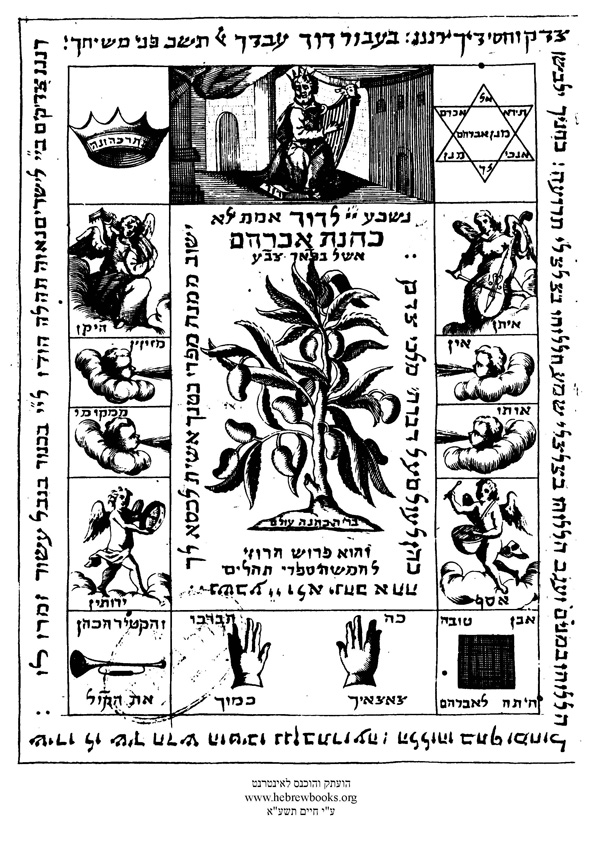

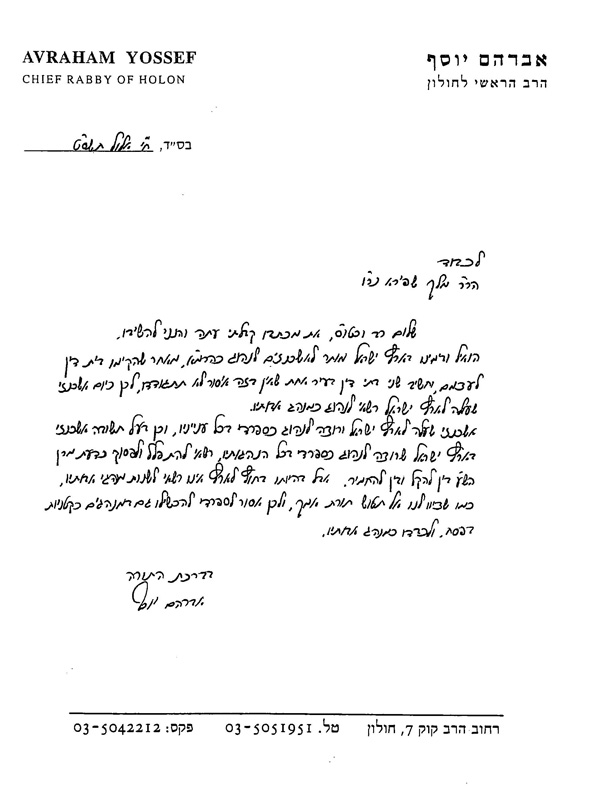

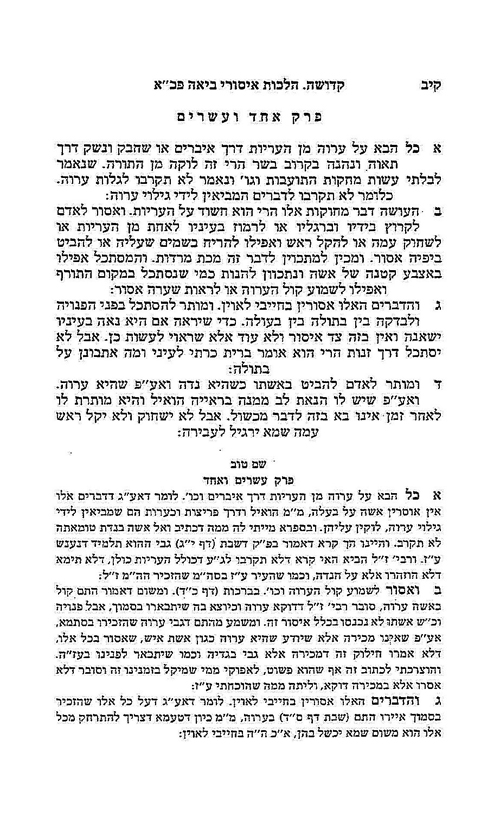

I haven’t yet mentioned the shawls that some women have started wearing (and which was the practice in the days of the Rambam; see Hilkhot Ishut 13:11) Most shawl-wearers are not so extreme as to completely cover their faces, and because of this the practice has been defended by some fairly mainstream people. According to R. Ovadiah Yosef’s son-in-law, R. Aharon Abutbol, and R. David Benizri, R. Ovadiah sees the practice in a positive light for those women who are able to take it on.[16] Among others who have spoken out in favor of the shawls are R. Yitzhak Ratsaby,[17] R. Avraham Baruch,[18] and R. Mendel Fuchs, a dayan for the Edah Haredit (who refers to the “heilige shawl”).[19] There is even a fairly recent book that discusses the matter in detail. It is Ahoti Kalah, by R. Avraham Arbel. Here is the title page.

Arbel is a great talmid hakham.[20] His book carries haskamot from mainstream figures, including R. Ovadiah, R. Neuwirth, and R. Nebenzahl. In the book, he explains the importance of the shawl, how women are not supposed to leave their home and if they must go out they should appear unattractive so that men are not drawn to them, and how it is absolutely forbidden for women to wear jewelry outside their home. (Recently, Arbel expanded the section of the book dealing with women’s tzeniut into a full-fledged book of its own.)

3. In the last post I quoted R. Kook’s comments about the holiness of the am ha’aretz. This is not a sentiment that has been widely shared among the rabbinic elite, and negative comments about the am ha’aretz abound in rabbinic literature from all eras. Most of these comments appear in non-halakhic contexts, but there are plenty that are found in classic halakhic works. See for example Shulhan Arukh, Yoreh Deah 198:48, where R. Moses Isserles states that if a woman coming home from the mikveh enounters a דבר טמא או גוי , if she is pious she will immerse again. This is obviously not so applicable today, as in any big city in the Diaspora, where people walk to the mikveh, it is impossible not to come across a non-Jew on the way home. The formulation of Rama was made in an era when Jews lived in their own quarters, and at night it wouldn’t be common to come into contact with non-Jews. On this halakhah, the Shakh quotes the Sha’arei Dura who expands the lists of things a woman hopes to avoid on the way home to include an am ha’aretz. (This formulation obviously troubled some, and Pithei Teshuvah quotes the opinion that only an am ha’aretz gamur is meant, i.e., one who doesn’t even recite keriat shema [due to his ignorance]. This definition of an am ha’aretz is found in Berakhot 47b and Sotah 22a. Examination of rabbinic literature shows that the term “am ha’aretz” has a variety of meaning, ranging from a simple ignoramus to one who is actually quite wicked and hates the Sages.)

Speaking of the am ha’aretz, here is something interesting, as it includes both a difficult comment of Rashi (actually, the commentary falsely attributed to Rashi) and what might be is an example of Artscroll purposely omitting mention of it because of how problematic it would be to explain. Nedarim 49a states: “Rav Judah said: The soft part of a pumpkin [should be eaten] with beet; the soft part of linseed is good with kutah. But this may not be told to the am ha’aretz.”

Why don’t we tell this to the am ha’aretz? Artscroll quotes the explanation of the Ran that if the boors knew about this, they would uproot the plants before they could be harvested. Tosafot claims that the ignoramuses won’t believe what we tell them and they will mock the teaching of the Sages. “Rashi” has a completely different explanation. He writes:

משום דדבר מעולה הוא לרפואה ואסור לומר להם שום דבר שיהנו ממנו

What this means is that we don’t let the am ha’aretz know about the medicinal property of this plant. In other words, we don’t want the am ha’aretz, even though he is another Jew, to benefit, and he is thus treated no differently than an idolater. (Tosafot cites this explanation and rejects it.) Even though “Rashi” is referring to a real am ha’aretz, as per the Talmud’s description in Berakhot 47b, it is still quite a shocking explanation. It is true that there is a passage in Pesahim 49b which states: “R. Eleazar said: An am ha’aretz, it is permitted to stab him [even] on the Day of Atonement which falls on the Sabbath . . . R. Samuel b. Nahmani said in R. Johanan’s name: One may tear an am ha’aretz like a fish.” Still, these passages are according to almost everyone not meant to be taken literally,[21] while “Rashi,” on the other hand, means exactly what he says.

[1] Many have discussed why Maimonides doesn’t explicitly record this halakhah in the Mishneh Torah. See the interesting approach of R. Hayyim Eleazar Shapira, Divrei Torah, Eighth Series, no. 18 (p. 974), which can be used to justify the Israeli haredi perspective.

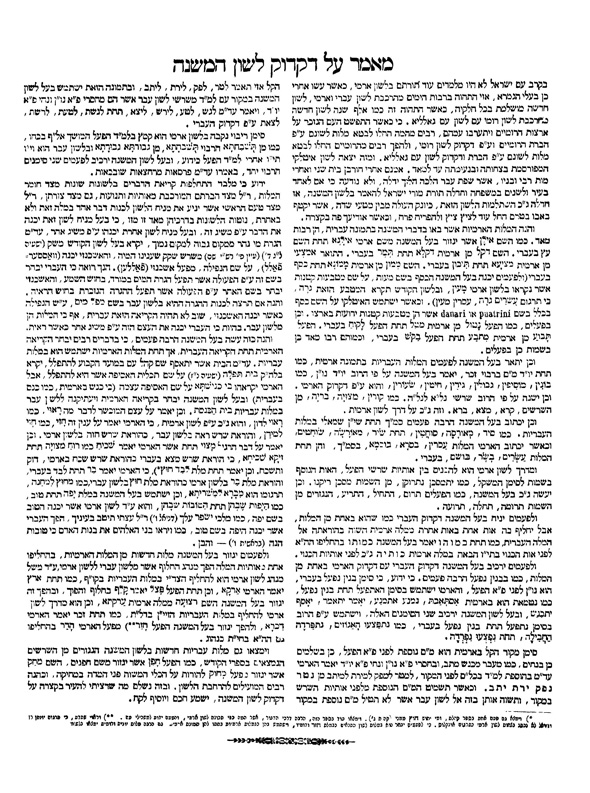

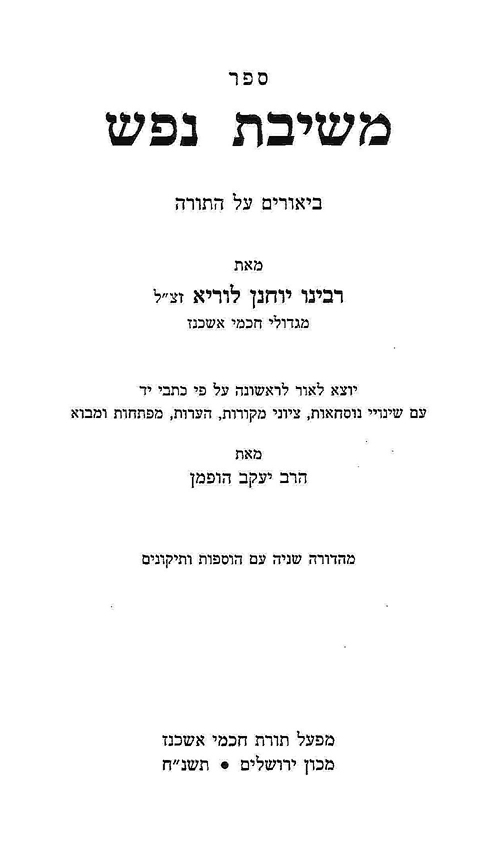

[2] See

Or Torah, Heshvan 5772, pp. 169-170. R. Mazuz’s own attitude towards yeshiva students preparing themselves to earn a living is seen in his haskamah to R. Hayyim Amsalem’s

Gadol ha-Neheneh mi-Yegio. The book is available

here.

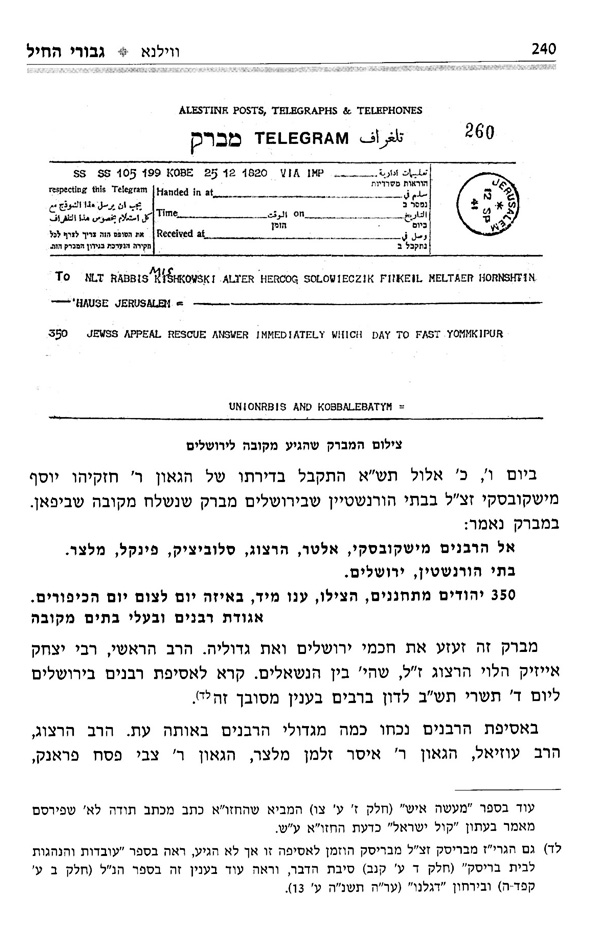

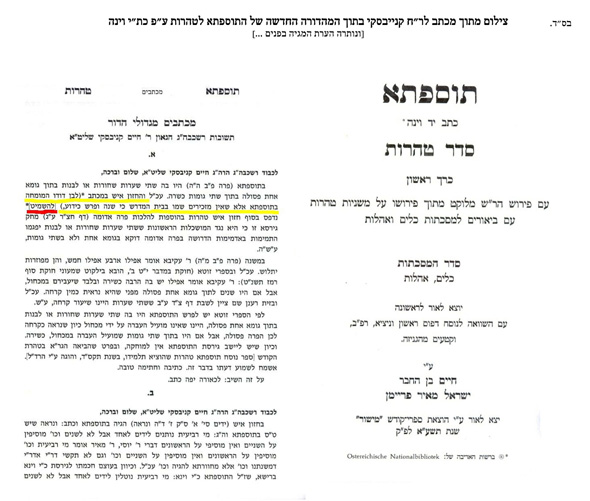

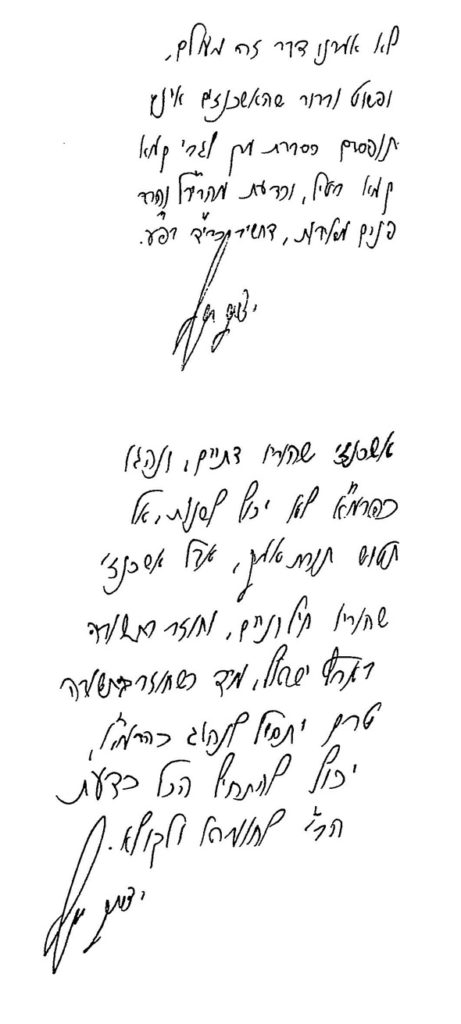

Here is R. Mazuz’s haskamah.

Here is the letter of R. Mazuz that appears at the end of the volume.

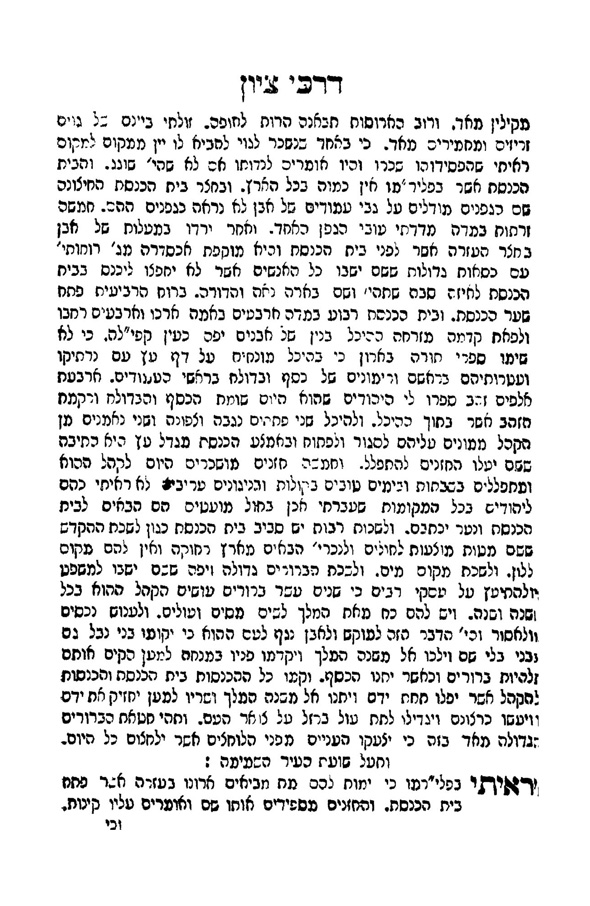

There are numerous texts I could bring in opposition to the approach of Amsalem and Mazuz (which I believe is also the approach of the Sages). One noteworthy one is found in Ateret Menahem, p. 23a, where R. Menahem Mendel of Rimanov is quoted as follows:

אם א’ אומר לחתנו היושב ולומד תורה בהתמדה שיתחיל לעסוק במו”מ עבור כי איתא [אבות פ”ב מ”ב] יפה ת”ת עם דרך ארץ וכו’, זה הוא מערב רב חו”ש

[3] See e.g., Naftali ben Menahem, Zemirot shel Shabbat (Jerusalem, 1949), p. 134.

[4] See Zev Rabiner, Or Mufla, p. 92.

[5] Barukh She-Amar, p. 238.

[6] See R. Meir Mazuz, Darkhei ha-Iyun, pp. 127ff.

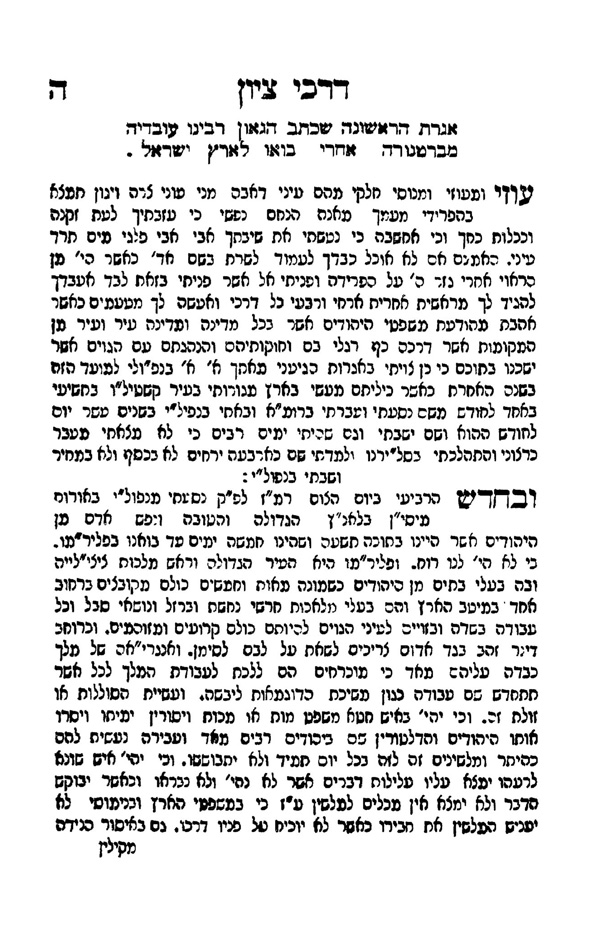

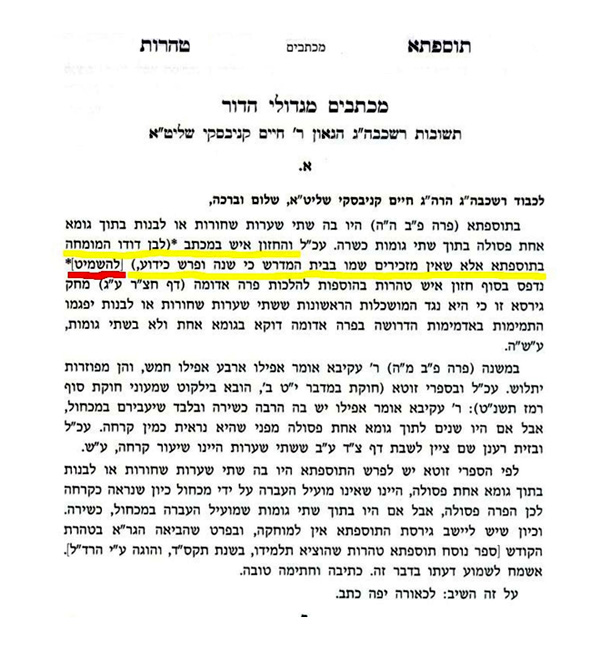

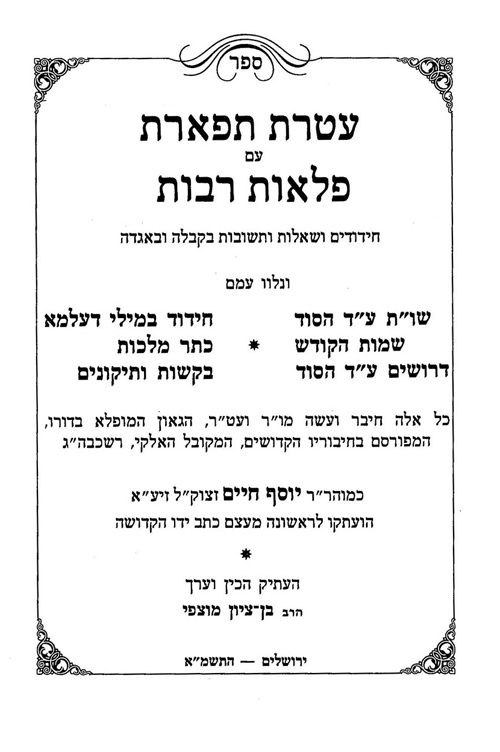

[7] Regarding not seeing women’s pictures, this position can also find sources to support it. R. Joseph Hayyim, Rav Berakhot, ma’arekhet tzadi (p. 137), writes quite strongly against women’s pictures, because men will come to look at them. Here is the page.

[8] For some, it is better if the women basically do not go out of the house at all at all. Such a position is held by R. Hayyim Rabbi, a mainstream Sephardic rabbi (who like all significant Sephardic rabbis, also has a website. See

here).

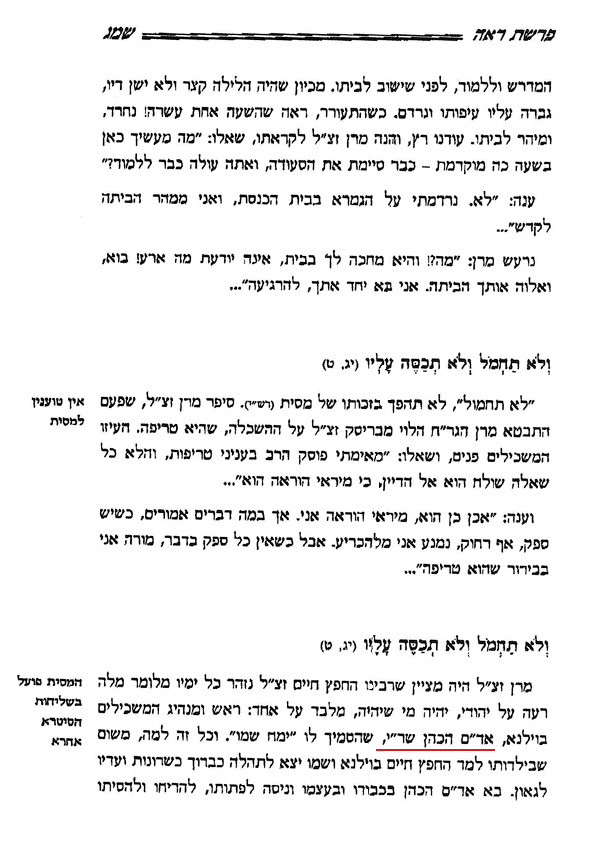

Here is his haskamah to R. Hanan Aflalo’s, Asher Hanan, vol. 3, and see Aflalo’s response that a rabbi has to actually be part of a community and know its situation in order to properly decide matters for it.

While Aflalo’s reply is phrased very respectfully, his feeling that Rabbi is way off base comes through very clearly.

Rabbi’s position about a woman not leaving the house can find support in a variety of traditional texts (not least, the Rambam, Hilkhot Ishut 13:11). What makes it significant is that he offers this advice even today. While it is true that in the Islamic world Jewish women were more accustomed to stay inside than their co-religionists in Europe, we also find European rishonim who see this as something to strive for. See e.g.,, Radak to 2 Samuel 13:2: ודרך הבתולות בישראל להיות צנועות בבית ולא תצאנה החוצה. See also Rashi, Deut. 22:23: פרצה קוראה לגנב הא אלו ישבה בביתה לא אירע לה. For other relevant sources, see R. Mazuz’s comment in R. Raphael Kadir Tzaban, Nefesh Hayah, vol. 2, p. 267.

I was surprised to find that the Moroccan R. Raphael Ankawa, in the twentieth century, ruled that a husband could forbid his wife from leaving the house without his permission. If she didn’t listen, she would lose her ketubah. See Toafot Re’em, no. 3. In a letter of support for Ankawa by R. Shlomo Ibn Danan and R. Mattityahu Serero they go so far as to state that if the woman doesn’t go along with the husband’s command and take an oath binding herself in this matter, the husband can, if he wishes, refuse to divorce her and she will remain an “agunah” her entire life without any financial support from him! He, of course, will be given permission to remarry.

ואם לא ירצה לגרשה תשב עד שתלבין ראשה ונותנין לו רשות לישא אשה אחרת אחר ההתראות הראויות והיא אבדה כתוב’ ואין לה לא מזונות ולא פרנסה ולא שום תנאי מתנאי הכתובה.

(As late as 1965, another Moroccan posek, R. Yedidyah Monsenego, ruled that where the husband had reason to suspect his wife of being unfaithful, he could require her to never leave home without him, even to visit relatives, except when she had to go to work. See Peat ha-Yam, no. 24)

All I can say is that contemporary women should be thankful that the RCA beit din and many of the rabbinic courts in the State of Israel have realized that in modern times men and women must be treated equally in the divorce proceedings, and women can no longer be held prisoner in a dead marriage as was often the case in earlier times. With this in mind, let me remind people that in an earlier post, available

here, I wrote as follows:

R. Hayyim Benveniste, Keneset ha-Gedolah, Even ha-Ezer 154, Hagahot Beit Yosef no. 59, in discussing when we can force a husband to give a divorce, writes:

ובעל משפט צדק ח”א סי’ נ”ט כתב דאפי’ רודף אחריה בסכין להכותה אין כופין אותו לגרש ואפי’ לו’ לו שחייב להוציא.

Can anyone imagine a posek, from even the most right-wing community, advocating such a viewpoint? I assume the logic behind this position is that even if the man is running after her with the knife, we don’t assume that he will actually kill her. He must just be doing it to scare her, and that is not enough of a reason to force him to divorce her. And if we are wrong, and he really does kill her? I guess the reply would be that this isn’t anything we could have anticipated even if we saw the knife in his hand, sort of like all those who have let pedophiles run loose in the yeshivot, presumably on the assumption that just because a man abused children in the past, that doesn’t mean that he will continue to do so.

(I will return to the issue of sexual abuse in a future post, because readers might recall that I expressed doubt that any rabbis would ever join the Agudah’s proposed rabbinic panel to determine if an accusation warranted going to the police. See

here. The Agudah has just acknowledged that it was impossible to form such a panel precisely because of the legal jeopardy it would place the rabbis in. See

here. Since it looks like all the public pressure will lead to clergy being made mandated reporters, it will be interesting to see what the Agudah response will then be. Will they instruct their followers to follow the law or expect them to go to jail in order to avoid mesirah?)

Regarding Aflalo’s point mentioned earlier in this note that a rabbi has to know the situation of a community, I recently found a very interesting comment by R. Levi Yitzhak of Berdichev, Kedushat Levi ha-Shalem (Jerusalem, 1958), Likutim, pp. 316-317. He asks why we say תשבי יתרץ קושיות ואבעיות, that in Messianic days Elijah will answer all problems. Since Moses will be resurrected, and he is the giver of the Torah, why don’t we say that he will provide the answers? R. Levi Yitzhak explains that only one who is living in this world knows what the situation is and how the halakhah should be decided. This is not the case with one who is dead and has lost his worldly connection. This explains why Elijah will provide all the answers, as he never died and was always part of the world. Therefore, unlike Moses, Elijah is the one qualified to decide matters affecting us. The lesson here is obvious, especially for those who think that every issue must be decided in Israel by authorities who really have really no conception of how American Jews live.

[9] I can’t tell you how often I have been with people (usually at Shabbat meals) who go on about how backwards the Muslims are, the proof being how they treat their women. This is usually contrasted to Judaism, which puts women on a pedestal. As an example of this “backwardness” people have pointed out that in Saudi Arabia (which is only one Muslim country, mind you), women are not even permitted to drive. I never have the heart to point out that there are hasidic sects, less than an hour away from where we are, that also don’t allow women to drive.

[10] See Ma’amar Esther, printed together with Va-Ya’an Shmuel (n.p., 2001), vol. 4, p. 19 (third numbering).

[11] Messas’ responsum is analyzed by Avinoam Rosenack, “Dignity of the Congregation” as a Defense Mechanism: A Halakhic Ruling by Rabbi Joseph Messas,” Nashim 13 (2007), pp. 183-206. On p. 201 n. 41, he provides references to scholarly literature that discusses medieval Jewish women’s adoption of Muslim modes of dress.

[12] Contrary to what Messas assumes, as far as I know there is absolutely no evidence that Jewish women generally dressed like this in the Rabbinic period. The fact that the Mishnah specifies the Arabian Jewish women shows that only one specific group dressed this way.

[13] Since he mentions women’s voices, let me return briefly to my second to last post which dealt with kol isha. I neglected to note the pesak of R. Abraham Yaffe-Schlesinger, Be’er Sarim, vol. 2, no. 54, who sees it as obvious that a woman is permitted to sing in front of non-Jews.

In the post, I mentioned three Modern Orthodox high schools that allow young women to sing solos. I was informed that the North Shore Hebrew Academy also has to be added to this list. See

here.

My correspondent further wrote: “I wanted to let you know that the son of Rabbi _____ (former president of the RCA [name deleted by MS]) told me that his father used to go to see Broadway shows based on the Psak of the Rav, who felt that if you couldn’t totally make out the face of the female singer it would be permitted.”

One of the commenters on the post called attention to R. Yehudah Herzl Henkin, Bnei Vanim, vol. 4, no. 7. In this responsum, he says a couple of things very relevant to the post. To begin with, he writes that it is permitted to listen to the singing of a single woman if this is something that you are used it, and it will not be sexually arousing.

לע”ד מדינא מותר לשמוע קול שיר של בתולות אם רגיל בקולן שאז שמיעתן זהה לראיית שערן

This is the same viewpoint I quoted from R. Jacob Pardo, who distinguishes between married women, whose singing is always forbidden, and single women whose singing is only forbidden if it is sensual song. Also noteworthy is that R. Henkin rejects the viewpoint found in various aharonim that a post-pubescent female (i.e., niddah) has the same status as a married woman, and her singing is therefore forbidden:

וכיון שנהגו להקל בשערן של בתולות ולא חלקו בין נדות לטהורות הוא הדין בקולן, כל שהוא רגיל בו ואינו מהרהר.

He concludes his responsum by stating that if the song is not sensual, and the woman’s voice is heard on the radio or out of a loudspeaker, since this is not really “her” voice it is permissible to listen. What this apparently means is that any time a woman sings into a microphone, it is permissible to listen to her (assuming her very appearance is not arousing). This basically gets rid of the entire kol isha prohibition in our time (when the songs aren’t sensual), since today every event with a woman singer uses a microphone. Based on R. Henkin’s responsum, all Modern Orthodox high schools could once more return to having young women sing solos (even though I am certain that this is not his intention).. Here is his conclusion (emphasis added):

ולא מפני שאנו מדמים נעשה מעשה להתיר לכתחילה לשמוע קול אשה המזמרת לפננו לבדה, אבל בשירה ברדיו או דרך רמקול וכו’ שעל פי דין אינה קולה ממש ובצירוף עוד טעמים [ראה להלן מאמר כ’] ובתנאי שהשירה אינה של עגבים נראה פשוט להקל.

In Bnei Vanim, vol. 2, p. 211, he quotes his grandfather as even permitting watching a woman sing on the television, because again, the voice is not her actual voice. He also notes that his grandfather later expressed doubt on this point.

שמעתי מפיו הקדוש שקול אשה על הרדיו אינו נקרא קול אשה ומותר לשמעו [בפעם הראשונה ששאלתי אותו על זה אמר בפירוש שגם בטלביזיה אינו נקרא קול אשה ומותר לשמעו, אבל כשחזרתי ושאלתי אותו על זה אחרי זמן לא היה ברור אצלו – ואולי מפני חולשתו]

In vol. 4, p. 30, he refers to a woman singing the national anthem, which based on his argumentation would, I think, be quite easy to permit, even watching on television. As he notes, this is not the sort of song that arouses sexual thoughts:

ורבים מקילים לשמוע קול שיר של אשה ברדיו כשהיא אינה לפניהם, ואינה שרה שירי עגבים אלא שירי מולדת וכיוצא באלה ורחוק שיהרהרו בה ואינו תלוי באם מכירה או לא.

I would also like to share an email I received from Benny Hutman which relates to R. Moshe Feinstein’s opinion. In my post I called attention to a responsum of R. Moshe Feinstein which I claimed cast doubt on R. Mordechai Tendler’s assertion that according to R. Moshe kol isha is entirely situational and depends on whether or not someone is aroused.

Benny writes:

It seems to me that R’ Moshe must hold that the prohibition on Kol Isha depends on whether a person is used to hearing women sing. R’ Moshe holds like the Aruch Hashulchan that nowadays one can say Shema in front of a woman with uncovered hair because the reality is that we are constantly confronted with such hair and therefore it is no longer arousing. For this to make sense we need to understand the Gemara in Berachos when it says “sear b’isha erva” to mean that hair could be ervah, meaning I would have thought that ervah by definition could only refer to parts of her body, ka mashma lan that hair despite not being skin can be ervah. However it won’t actually be ervah unless it is normally covered. Since the language of the Gemara is exactly the same (as is the source) it follows that the gemara means that Kol Isha could be ervah despite not physically being attached to the body at all. However, just as R’Moshe says that our constant exposure to uncovered hair makes sear no longer be ervah, the same logic dictates that if someone has been listening to women sing all his life kol isha will not be ervah. Arguably it can also be situational so that if someone has been going to the opera all his life such singing will not be kol isha, but pop music will be. It seems to me that this heter should apply to almost all Modern Orthodox men. This would explain how Rabbi Tendler could say that R’ Moshe held that the prohibition is situational despite R’ Moshe’s tshuva apparently holding it is forbidden. It depends on who is asking the question and the time, place and manner of the singing.

Finally, R. Hayyim Amsalem, in his recently published Derekh Hayyim, p. 45, states that it is a well known fact that great Torah scholars and chief rabbis have in the past been present at various official events that included women singing, and they did not walk out. As he explains:

הם ידעו לחשב שכר “מצוה” כנגד הפסדה, ושגדול כבוד הבריות שדוחה לא תעשה שבתורה (ברכות דף יט ע”ב), שלא לדבר על העלבת פנים העלולה להגרם, והרי המלבין פני חברו ברבים אין לו חלק לעוה”ב (בבא מציעא דף נט ע”א), יתכן וכשהיו יכולים להשתמט מלהופיע בטקס כזה שידעו מראש שיכלול גם שירת נשים היו נמנעים מלהופיע, אבל היכן שההכרח אלצם להשתתף הרי שמעולם לא נשמע רינון אחריהם על השתתפותם, או על העלבת המעמד ביציאה פומבית.

[14] Rosenack writes (“Dignity”, p. 190): “Messas’s remarks allow the inference that he knew of an ancient tradition—either from the days of his own ancestors, or from the time of the talmudic sages—of women going up to the Torah, before the institution of the [talmudic] prohibition discussed here.” This is incorrect. What Messas is doing in this responsum is describing what he imagines the situation was like in the era that women received aliyot, and why this was later prohibited. There is not even the hint that he knew of any ancient tradition in this regard, and he certainly did not.

In terms of women’s aliyot, in my post

here I called attention to R. Samuel Portaleone’s opinion that in theory it is permitted to give a woman an aliyah in a private synagogue. Without knowing of Portaleone’s view, R. Yehuda Herzl Henkin concluded that ”if done without fanfare, an occasional

aliyyah by a woman in a private minyan of men held on Shabbat in a home and not in a synagogue sanctuary or hall can perhaps be countenanced or at least overlooked.” “

Qeriat Ha-Torah by Women: Where We Stand Today,”

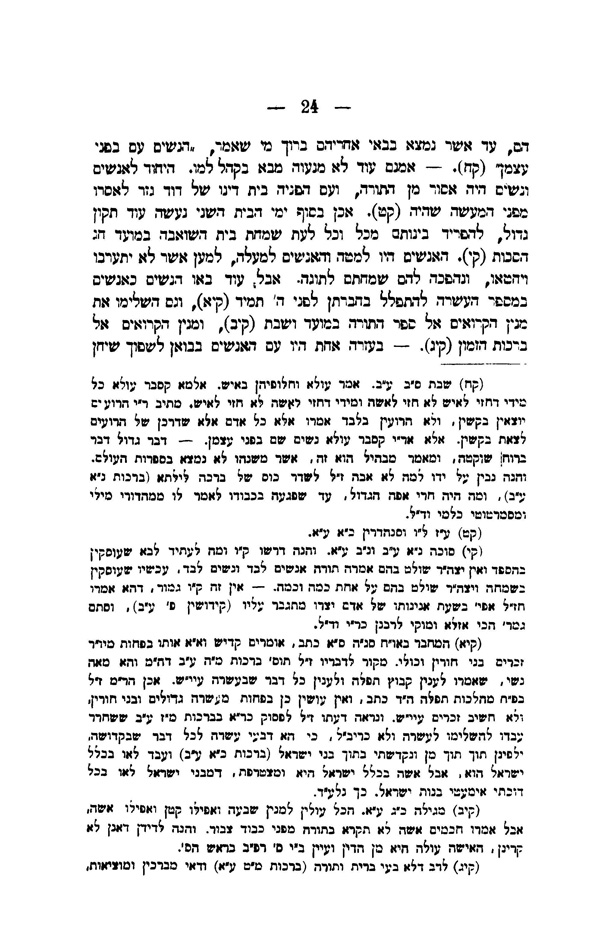

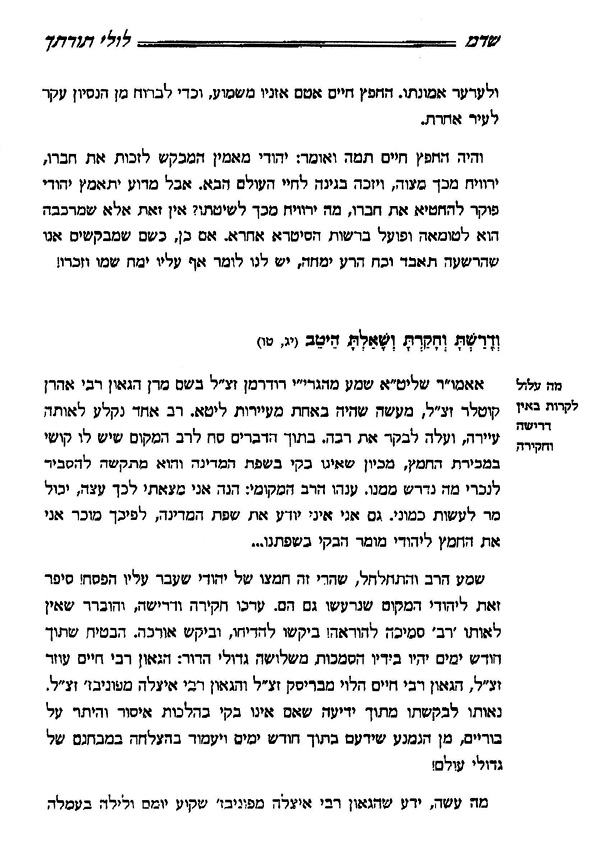

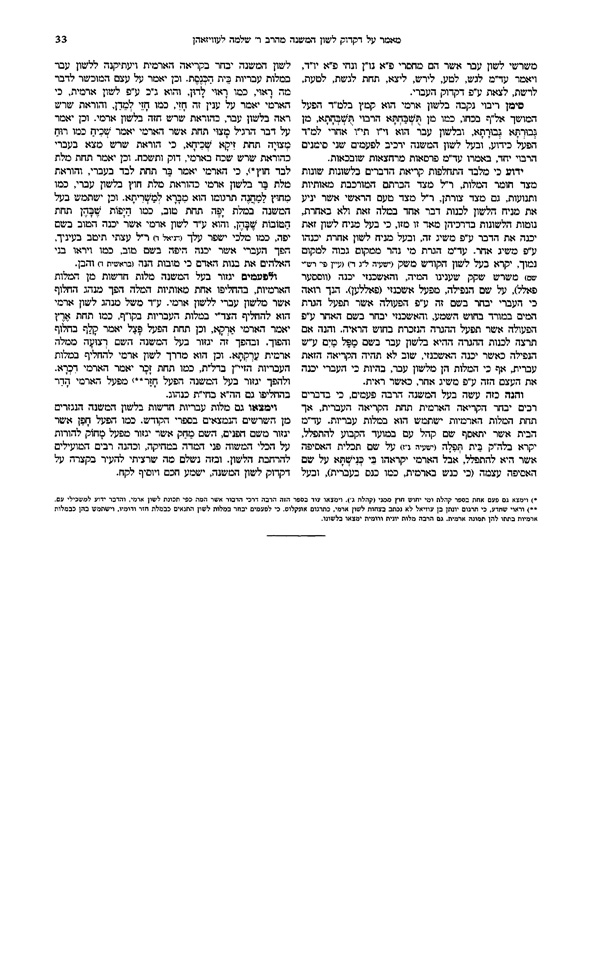

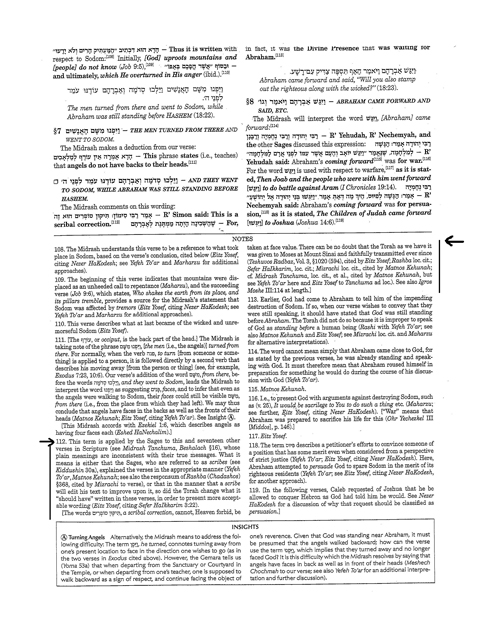

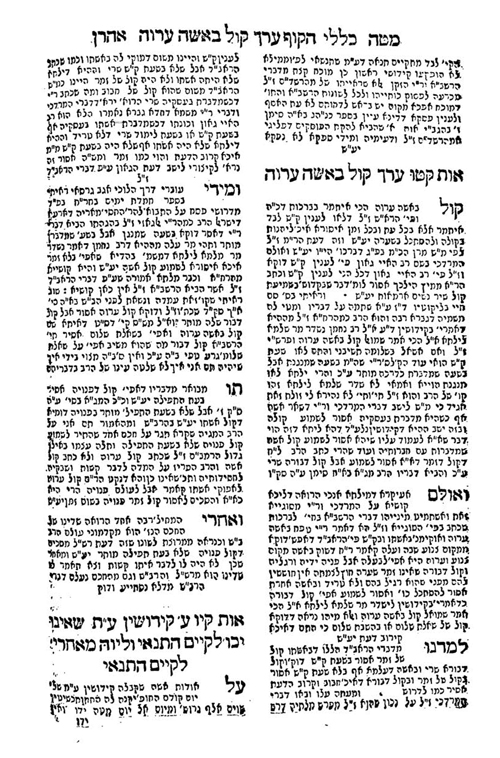

Edah Journal 1:2 (5761), p. 6. (Henkin also assumes that women’s aliyot on Simhat Torah are permissible.) There is another source in this regard that has been overlooked by those arguing for women’s aliyot in so-called partnership minyanim (I hate this term!). R. Moses Salmon,

Netiv Moshe (Vienna, 1899), p. 24 n. 112, sees no problem with women getting aliyot today. As mentioned already, women are denied aliyot because of

kevod ha-tzibur. Yet according to Salmon, since today men who get aliyot no longer read from the Torah,

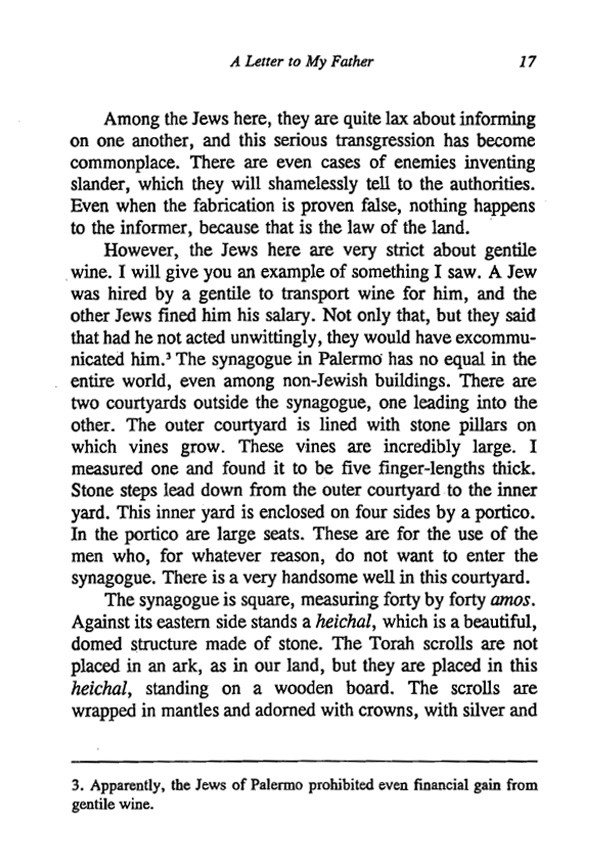

kevod ha-tzibur is no longer a concern. This was all theoretical for Salmon, as no one in his Hungarian town was dreaming of calling women up to the Torah, but from the standpoint of pure halakhah, he saw no objection. He also claims that according to Maimonides, women can be counted in a minyan. See ibid., n. 111. Here is the page from Salmon.

[15] The same approach is adopted by R. Matzliah Mazuz, Ish Matzliah, vol. 1 no. 10. He writes:

לע”ד כבוד ציבור דהתם, אינו כפשוטו, אלא לישנא מעליא, ועיקר הכוונה כאותה ששנינו בסוכה דנ”א תיקון גדול

[17] See

here and

here. See also his

Shulhan Arukh ha-Mekutzar, vol. 6, pp. 246ff., and

here for a placard signed by some leading Sephardic rabbis.

[18] See

here. He thinks that a woman who refuses to say good morning to her male neighbor is demonstrating proper tzeniut.

[20] Incidentally, in no. 328:2, he states that there is no longer a problem taking medicine on Shabbat, since people today do not grind their own medicine.

- [21] See the numerous explanations of these passages in R. Moshe Zuriel, Leket Perushei Aggadah, ad loc. Tosafot, ad loc., quotes one opinion that does take the passage literally, but this opinion assumes that the am ha’aretz spoken of is a violent person suspected of murder