German Orthodoxy, Hakirah, and More

Marc B. Shapiro

1. I recently published a translation of Hirsch’s famous lecture on Schiller. You can see it

here.

At first I thought that this lecture remained untranslated into English for so long because of ideological concerns. (I still think that this is the reason it was never translated into Hebrew.) Yet before the article appeared, I was informed that the reason it did not appear in the English translation of the Collected Writings of Hirsch was not due to ideological censorship, but censorship of a different sort (see the article, note 2). I will let readers decide if this was a smart choice or not. I plan on publishing another translation from Hirsch which has also never appeared in English or Hebrew, and which many people will regard as not “religiously correct” for the twenty-first century.

With regard to the Schiller lecture, I thank Elan Rieser who called my attention to the following: Hirsch quoted Schiller as saying about a plant, “What it [the plant] unwittingly is, be thou of thine own free will.” It so happens that this very thought also appears in the Nineteen Letters, Elias translation, p. 56: “The law to which all forces submit instinctively and involuntarily—to this law you, too, are to subordinate yourself, but consciously and of your own free will.” This shows that even in his earliest work, Hirsch was influenced by Schiller.

While on the topic of non-Jewish writers influencing German rabbis, here is another example which might lead some to wonder if we have crossed the line from influence into plagiarism. (I do not think so, as I will explain.) Rabbi Marcus Lehmann (1831-1890) was a well-known German Orthodox rabbi. He served as rabbi of Mainz and was founder and editor of the Orthodox newspaper Der Israelit. Apart from his scholarly endeavors, he published a series of children’s books, and is best known for that. These were very important as they gave young Orthodox Jews a literature that reflected traditional Jewish values and did not have the Christian themes and references common in secular literature. Yet despite their value for the German Orthodox, R. Israel Salanter was upset when one of Lehmann’s stories (Süss Oppenheimer) was translated into Hebrew and published in the Orthodox paper Ha-Levanon. Although R. Israel recognized that Lehmann’s intentions were pure and that his writings could be of great service to the German Orthodox, it was improper for the East European youth to read Lehmann’s story because there were elements of romantic love in it. This is reported by R. Isaac Jacob Reines, Shnei ha-Meorot, Ma’amar Zikaron ba-Sefer, part 1, p. 46. Here is the relevant passage:

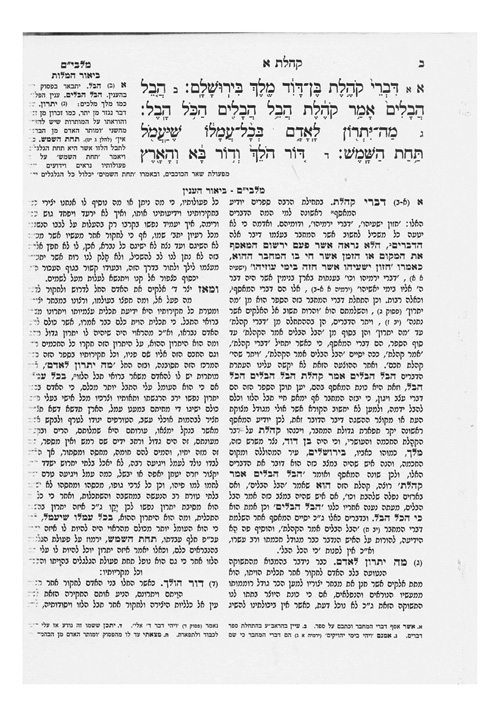

והנה ברור הדבר בעיני כי הרה”צ רמ”ל כיון בהספור הזה לש”ש, ויכול היות כי יפעל מה בספורו זה על האשכנזים בכ”ז לא נאה לפני רב ממדינתינו להעתיק ספור כזה שסוף סוף יש בו מענייני אהבה.

This passage is followed by another, which was made famous by R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg in Seridei Esh, vol. 2 no. 8. This is Weinberg’s well-known responsum on co-ed groups. He describes how R. Israel Salanter visited R. Esriel Hildesheimer and saw him giving a shiur in Tanakh and Shulhan Arukh before young women. R. Israel commented that if a rabbi from Lithuania would institute such a practice in his community they would throw him out of his position, and rightfully so. Yet he only hoped that he would be worthy enough to share a place in the World to Come with Hildesheimer: הלואי שיהי’ חלקי בג”ע עם הגה”צ ר”ע הילדסהיימר.

Weinberg doesn’t say where he learnt of this story, but it comes from Reines, who heard it directly from R. Israel Salanter. Yet Weinberg’s recollection was not exact. Before World War II, Weinberg had access to Shnei ha-Meorot, and he refers to it in his essay on Reines (Seridei Esh, vol. 4, p. 355, originally published before the War). After the War he no longer had access to this book, and thus was not able to check R. Israel Salanter’s exact words. Although, based on Weinberg, people often repeat Salanter’s comment that he hopes for a share of the World to Come together with Hildesheimer, he never actually said this. Here are his words, as recorded by the only witness, Reines, and I hope that from now on the great R. Israel Salanter will be quoted accurately. (The passage in the parenthesis is a comment from Reines himself.)

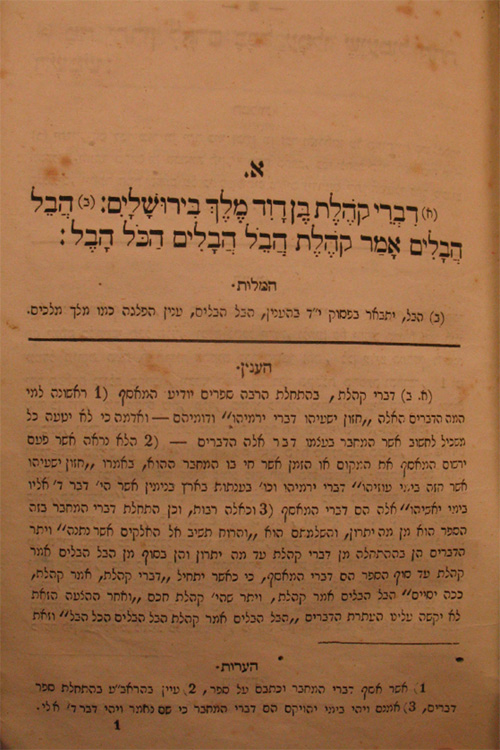

הלכתי לבקר גם את ביה”ס אשר לבנות, ששמעתי שגם שם מגיד הרה”ג הנ”ל [הילדסהיימר] איזה שעור, ומצאתי שבחדר גדול ורחב ידים עומד באמצע שולחן גדול וסביב השולחן יושבות נערות גדולות, והרה”ג הנ”ל בראש השלחן מגיד לפניהם שעור בשו”ע (הוא אמר לי אז גם באיזה הלכה שאמר להם אבל שכחתי) והוסיף לומר בזה”ל “ברור הדבר בעיני כי כוונת הרב היא לש”ש, וגם נעלה הדבר בעיני מכל ספק, כי כל התלמידות האלה השומעות לקח מפיו תהיינה לנשים כשירות, תמלאנה כל המצות שהנשים חייבות בהן, תחנכנה ילדיהן על דרכי התורה והאמונה, באופן שיש לומר בוודאות גמורה ומוחלטת כי הרה”ג הנ”ל עושה בזה דבר גדול באין ערוך, בכ”ז ינסה נא רב במדינתינו לעשות ב”ס כזה, הלא יקראו אחריו מלא ומן גיוו יגרשוהו; ואין ספק כי יהי’ מוכרח לנער את חצני’ מן הרבנות כי לא תהלמו עוד”, כל הדברים האלה דבר הרה”ג הצדיק הנ”ל בהתרגשות מיוחדה והתלהבות יתירה

Returning to Lehmann, one of his short stories is titled

Ithamar. Eliezer Abrahamson called my attention to the fact that chapter 17 tells the same story as is found in Lew Wallace’s classic American novel,

Ben-Hur, Book 3, chs. 2-3. I prefer to call this “borrowing”, rather than plagiarism, since

Ben-Hur was a worldwide sensation and Lehmann was not trying to hide his borrowing. At that time, any adult reading Lehmann’s book would know what he was basing the chapter on, and that he was providing a Jewish version of certain episodes. In fact, the name of the main character of Lehmann’s book, Ithamar (not a very common name), is also the name of the father of the main character of

Ben-Hur (Judah ben Ithamar ben Hur). By naming his character Ithamar, Lehmann was signaling his debt to Wallace.

[1]

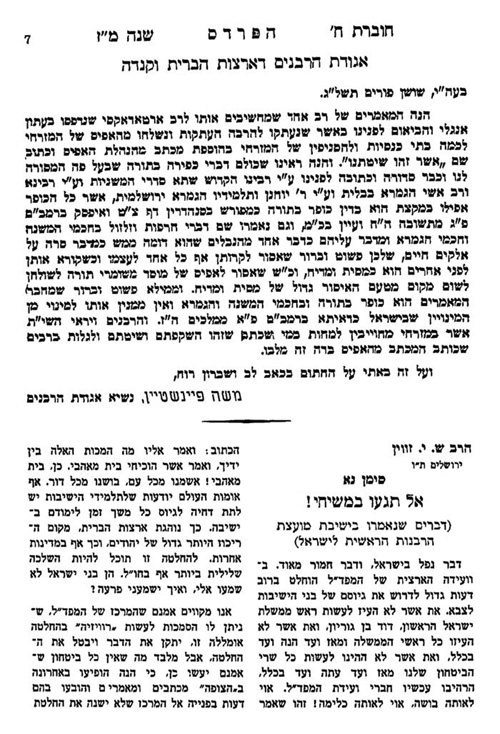

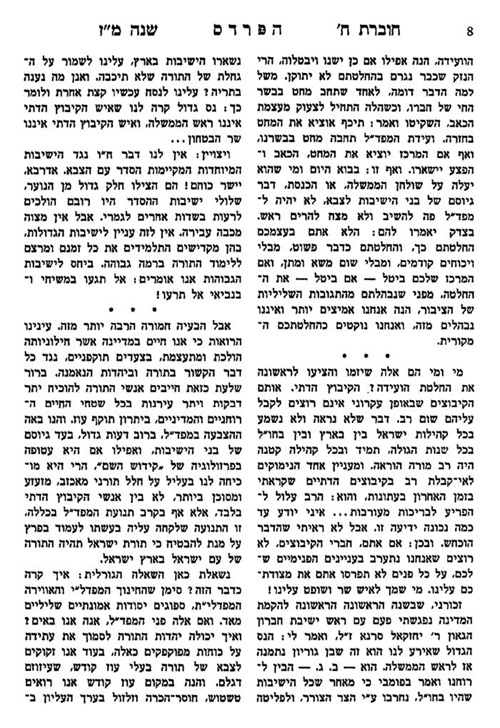

Regarding Lehmann’s stories, in the 1990s they also appeared in a censored haredi version.

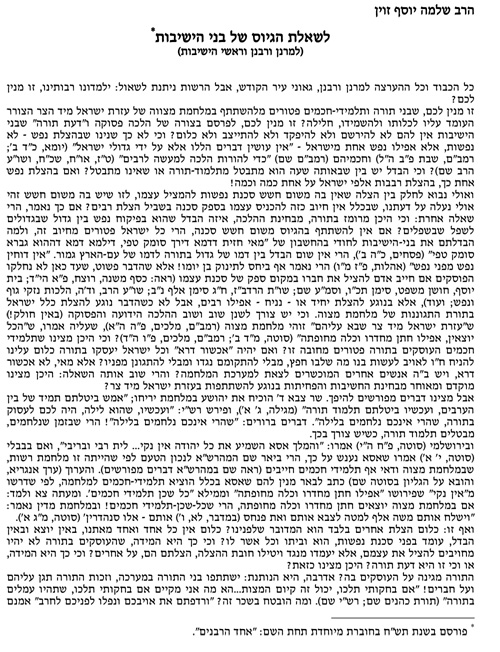

Ha-Modia actually published an article attacking this “reworking”. Here it is, followed by the response. (You can right-click to open larger images, or download it as a pdf

here.)

I found these on my computer and don’t remember anymore how I got them (and unfortunately, there is no date visible on the articles). Click them to enlarge.

2. Not too long ago

Hakirah 13 (2012) appeared, and as with the previous issues, it is a great collection of articles. The other Orthodox journals have to ask themselves why

Hakirah has been so successful in overshadowing them. I think the answer is obvious.

Hakirah is not afraid to take risks in what they publish. They don’t mind rocking the boat a bit, and dealing with controversial matters. I want to respond to two articles in the issue. The first is R. Elazar Muskin’s piece in which he discusses a 1954 Yom ha-Atzmaut event in Cleveland, which featured R. Elijah Meir Bloch, the Rosh Yeshiva of the Telz yeshiva. From the article one sees that Bloch had a positive attitude towards the State of Israel. Before reading further, I suggest people look over Muskin’s article again, so you can best appreciate that which will follow. You can find the article

here.

Muskin notes that Bloch’s letter justifying his appearance at the Yom ha-Atzmaut event was published in R. Joseph Epstein’s 1969 book Mitzvot ha-Shalom. Although there have been many books that express a positive, or tolerant, view towards Zionism, anti-Zionist extremists chose to focus on this volume. Muskin quotes Gerald Parkoff who wrote as follows in a letter published in the Torah u-Madda Journal 9 (2000), p. 279:

When the first edition of the Mizvot ha-Shalom was published, the unsold inventory, which represented most of the extant copies, was kept in Rabbi Epstein’s garage. As it turned out, the sefer came to the attention of some misguided people[2] who were particularly upset with Rabbi Epstein’s association of Rabbi Eliyahu Meir Bloch with Yom ha-Azmaut. They proceeded to burn the first edition of Mizvot ha-Shalom in Rabbi Epstein’s garage. Subsequently, the perpetrators of this dastardly act were found and brought to a Satmar Bet Din. Financial restitution was then made to Rabbi Epstein.

As Parkoff notes, when the next edition of the work was published, Epstein took out Bloch’s letter, so as not to have another confrontation with the extremists. Yet something doesn’t make sense. Why would Satmar (or Satmar-like) extremists care about a letter from Bloch in Epstein’s book? What does this have to do with them? The extremists certainly had no interest in defending the honor of an Agudist whose ideology is rejected by them just as they reject the Mizrachi position. So why would they care about Epstein’s book at all?

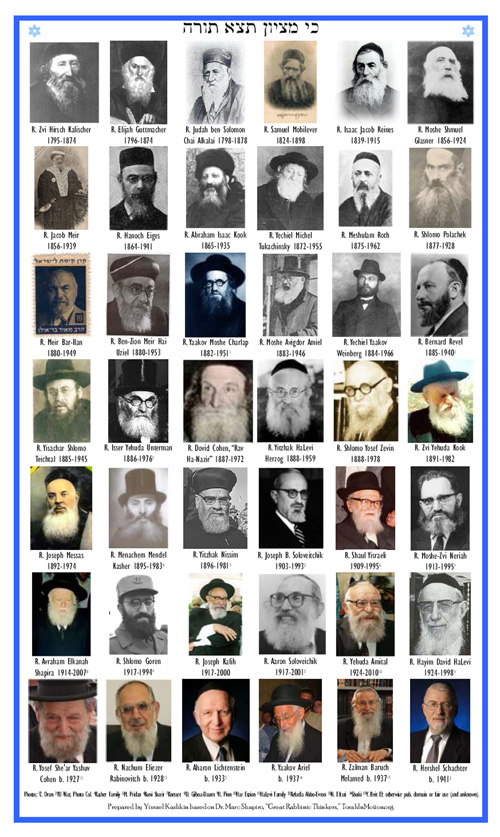

If you compare the first edition of Mitzvot ha-Shalom to the second edition, the answer is, I think, obvious, and it has nothing to do with the Bloch letter. Pages 605-624 from the first edition are omitted in the second edition. The first few pages of this is Bloch’s letter, but beginning on p. 612 there is a section titled “Al ha-Geulah ve-al ha-Teshuvah.” This section is a rejection of R. Joel Teitelbaum’s views (in which, by the way, Epstein refers to the writings of R. Zvi Hirsch Kalischer, R. Yissachar Shlomo Teichtal, and R. Menachem M. Kasher). The very title of the section is an allusion to the Satmar Rav’s book, Al ha-Geulah ve-al ha-Temurah. While Epstein’s views are expressed respectfully, it is easy to see why the extremists would have gone after him, as a means of upholding the honor of their Rebbe. They presumably also saw the following passage, p. 611, as directed against the Satmar Rav, and even if it wasn’t directed against him personally, it is certainly directed against his followers.

אמנם השטן מרקד בין תלמידי חכמים על תלמי הפירוד והפילוג בישראל להטיל קטטיגוריא ביניהם, עד כדי השמצת שמות אהלי תורה ויראה, ועד כדי הורדת כבוד גדולים ארצה בכתבי פלסתר והוצאת דיבה, ללא חשש הלבנת פנים, וחטא מבזה תלמיד חכם, ונמצאים נכשלים בחטאים יותר חמורים מאלה שבאו לצעוק עליהם.

On p. 615 he writes as follows (even referring to the Satmar Rav’s views as “has ve-shalom”):

עיני גדולי וצדיקי הדור רואים נסים ונפלאות (ראה לעיל מבוא, מ”מ 32) – קול דודי דופק – אם אתחלתא דגאולה, אם רק פקידה, אם רק רמז רמיזה “מן החרכים” מאבינו שבשמים לריצוי, לפיוס – בהדי כבשי דרחמנא למה לן – איתערותא דלעילא הקוראת לאיתערותא דלתתא – וכי כל זה אך אור מתעה הוא חו”ש? (ראה “על הגאולה ועל התמורה עמ’ כ’ . . . )

I found a relevant “open letter” in the R. Leo Jung archives, File 2/1, at Yeshiva University. I thank the Yeshiva University Archives for permission to reproduce the letter here.

From this letter we see again that the issue had nothing to do with Bloch. Yet since there were other people attacking the Satmar Rav’s views during this time, I still think we need an explanation as to why these crazies decided to focus on Epstein. From the “open letter” it would appear that this was just another way to attack R. Moshe Feinstein, who wrote a haskamah for Epstein. In the “open letter” it states that if R. Moshe does not retract his haskamah then those behind the letter will take action. This action no doubt includes the burning of Epstein’s sefer.[3]

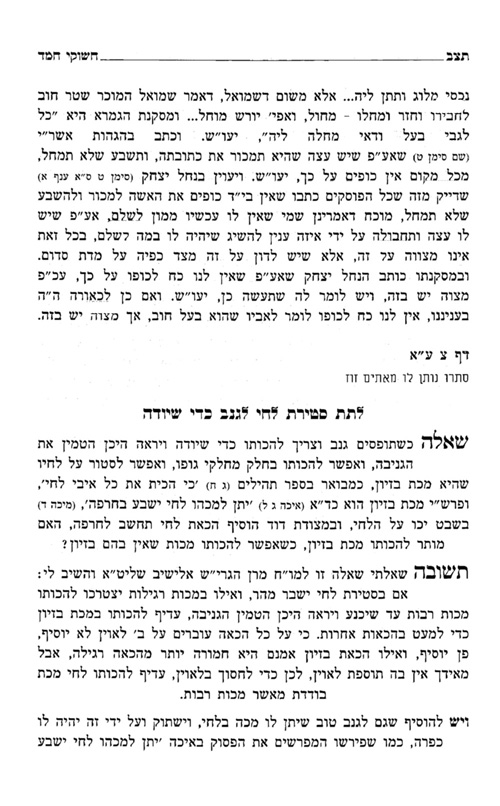

Here is how these wicked people expressed themselves, sounding just like mobsters:

משה’לע תדע שזה היא האזהרה האחרונה שאם לא תתחרט ברבים על ההסכמה שכתבת להספר הנ”ל לא נבוא עוד בכתב רק בידים נעשה מעשים נבהלים שתסמר שערות ראשך שתבוש להראות פרצופך הטמא.

Regarding R. Elijah Meir Bloch, he was a real Agudist, even serving on the U.S. Moetzet Gedolei ha-Torah. Yet his positive view of the establishment of the State of Israel is not unexpected. I say this because his father, R. Joseph Leib Bloch, Rosh Yeshiva of Telz and also rav of the city – the combination of rosh yeshiva and city rav was not so common

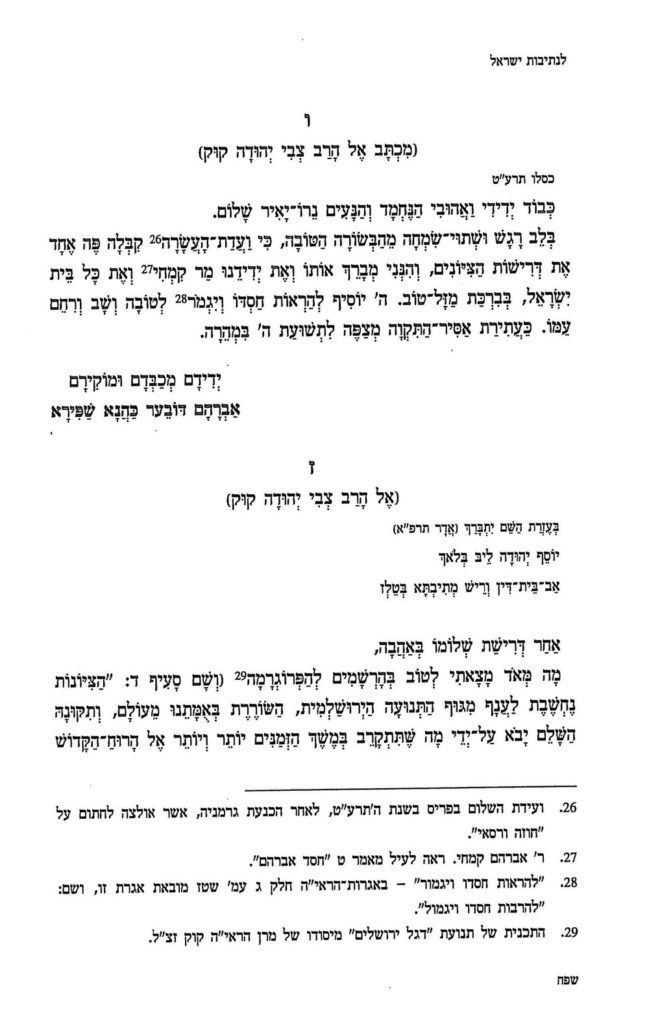

[4] – appeared to be inclined to a type of Religious Zionism. Here is his letter to R. Zvi Yehudah Kook, published in the latter’s

Li-Netivot Yisrael (Beit El, 2001), vol. 1.

I realize that R. Joseph Leib Bloch is usually portrayed as a strong anti-Zionist. This needs further investigation, but it could be that his opposition was only against secular Zionism and what he regarded as the Mizrachi’s compromises with the secular Zionists. From his letter, we see that he had a much different view of R. Kook’s Degel Yerushalayim.[

5]

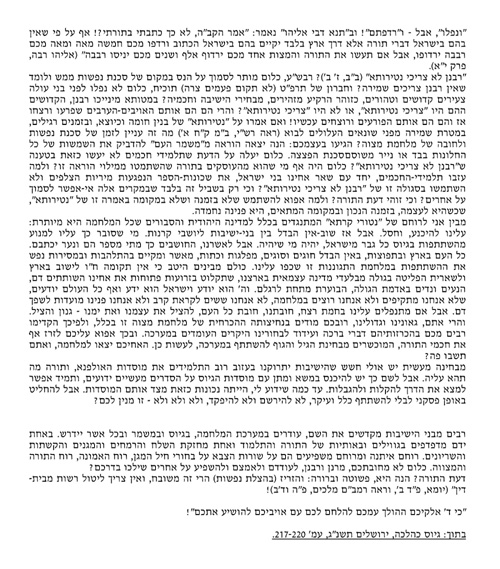

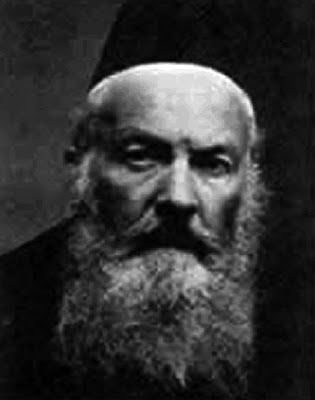

The letter above that of R. Joseph Leib Bloch is from R. Avraham Shapiro, the Kovno Rav, who unlike many other Lithuanian gedolim was a real opponent of Agudat Israel. (Another noteworthy opponent was R. Moses Soloveitchik.) Here is R. Shapiro’s picture.

R. Shapiro also was a supporter of Religious Zionism and a great admirer of R. Kook. Unfortunately, we don’t yet have a biography of his life. Those who want to know a little more about his attitude towards Zionism can see his 1919 letter to R. Kook in Iggerot la-Re’iyah, no. 94. Here he writes as follows:

החלטנו שבהמעשים הפוליטיים להשגת חפצנו באה”ק, כלומר העבודה לפני אסיפת השלו’, נלך ביחד עם הציונים שלא בהתפוררות כבאי כח מפלגה ומפלגה, כי אם כבאי כח כל העם העברים בסתם. למטרה זו נבחרה קומיסיה פוליטית לבוא בדברים עם הציונים, וכבר נעשה הצעדים הדרושים לזה. מקוה אני שתמצא הדרך להתאחדות הפעולות.

We see very clearly from this letter that the Kovno Rav supported working with the non-Orthodox Zionists in order to achieve the Zionist objective, which became a real possibility after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War 1.

In a 1921 letter to R. Zvi Yehudah Kook, Iggerot la-Re’iyah, p. 557, the Kovno Rav refers to the Agudah paper Ha-Derekh in a mocking tone: כפי שראיתי מ”הדרך” לא-דרך. In this letter he tells R. Zvi Yehudah that it is important for the Orthodox in Palestine to be involved in the political process that was set up by the British Mandatory authorities. Yet instead of doing that, he claims that the Orthodox have turned a large portion of the women against them, alluding towards the Eretz Yisrael rabbis’ ruling forbidding women’s suffrage, a ruling which R. Avraham Yitzhak Kook was at the forefront of. Look at these words and remember that the one writing them was one of the greatest poskim of his time, the great rav of Kovno, not some minor Mizrachi figure:

האומנם חושבים הם את השתתפות הנשים לאיסור גמור המפורש בתורה שאין אומרים בו מוטב יהיו שוגגים כו’? לדעתי הסכילו עשה.

This opposition to women voting in Israeli elections has disappeared from the haredi world, for obvious political reasons. Yet examination of haredi writings leads to the conclusion that female suffrage is only a hora’at sha’ah, and that if the haredim ever became a majority the right to vote would be removed from women. But I think that this is more theory than reality, as I can’t imagine that even a haredi society would take this step as the backlash from women would be quite significant. As for the followers of R. Kook, do they also think that female suffrage is hora’at sha’ah and hope for a day when the vote will be taken away from women, for all the reasons R. Kook offered? Based on a recent statement by R. Aviner, it appears that for some of them the answer to this question is yes.

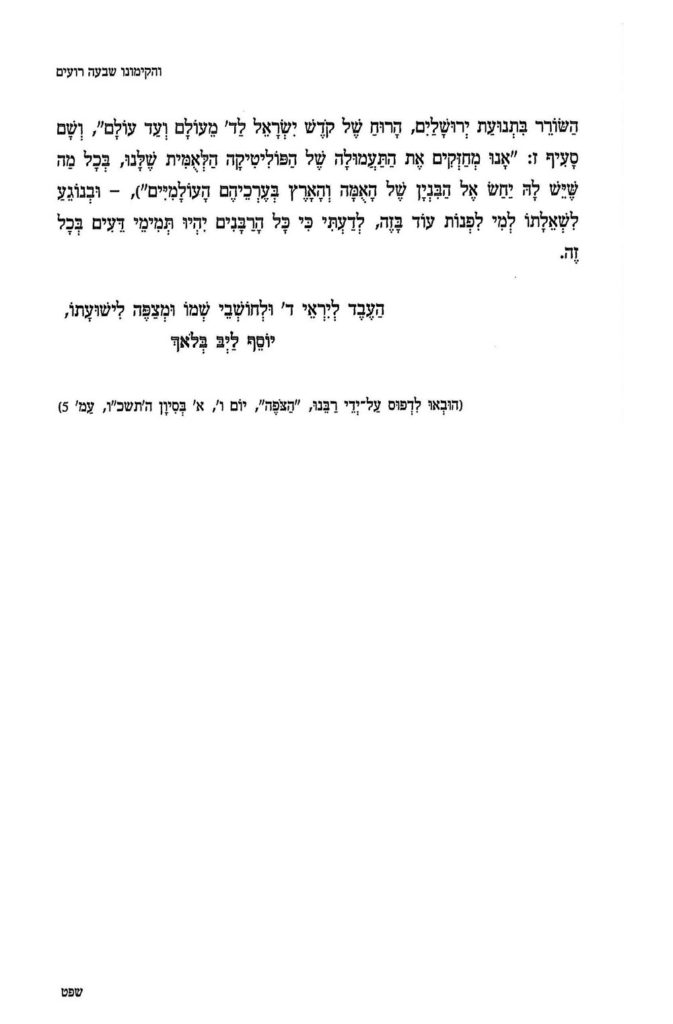

The Kovno Rav ends his letter to R. Zvi Yehudah with these strong words against Agudat Israel:

כנראה אסע אי”ה בקרוב בשביל צרכי צבור ללונדון. כמובן לא בשביל אגודת-ישראל. כנראה אחר כ’ את האספה בפ”ב. מה דעתו עליה? אנכי בכוונה לא נטלתי חלק בה, לפי שכל מעשיהם עד עכשיו אינם רצוים בעיני ואינם בדרך האמת. הדו”ח של רוזנהיים לא הי’ אמת. הקומיסא הפוליטית איננה יודעת מאום מאשר עשו ולכה”פ אנכי איני מסכים על כל דרכיהם שהזיקו רק להאורטודקכסיא ולא לאחרים. אני אומר זאת לכל מפורש מבלי התחבא בהשקפתי.

I mention the Kovno Rav’s opposition to Agudat Yisrael not only for its historical significance, but also because it brings us back to a time when Agudat Israel actually did something other than put on a big Daf Yomi celebration every seven years.

[6] There was a time when Agudat Israel tried to accomplish great things, so there was reason to oppose it by those who thought that it was moving in the wrong direction. Today, however, what is Agudat Israel? There was a time when it was a movement, and today it is a lobbying organization, pure and simple, and without much influence at that. I guess that’s what happens when you don’t even have a website or a journal. You sink into oblivion, only to be remembered in another seven years at the next Siyum ha-Shas.

In a 1931 letter to R. Kook,

Iggerot la-Re’iyah, no. 273, the Kovno Rav asks R. Kook if he agrees with him that a world congress of rabbis should be convened – אספת רבנים עולמית . I mention this only because in later years it became almost an article of faith in the haredi world that such rabbinic gatherings were absolutely forbidden. The fear was that the gatherings would make decisions at odds with the haredi Daas Torah. The only way to make sure that their followers would not attend these gatherings, where they might actually hear different viewpoints, was for the haredi leaders to ban these gatherings.

[7] This is as good an example of any of how the haredi leadership uses its rabbinic “muscle” for political goals. If someone were to ask on what basis can one state that it is forbidden for rabbis with different viewpoints to gather to discuss issues, the answer is obviously not going to be that the Talmud or

Shulhan Arukh says it is forbidden. It is forbidden because the gedolim say it is forbidden, i.e., Daas Torah.

R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg writes as follows about the Kovno Rav (Kitvei ha-Rav Weinberg, vol. 2, p. 234):

ועלי להעיר כי הגאון דקאוונא שליט”א הוא אחד מגדולי הדור בזמננו, אחד המוחות היותר טובים שבתוכנו. ואעפ”י שאנשים ידועים משתדלים להשפילו ולהמעיט את ערכו, מ”מ אי אפשר להחשיך את אור תורתו וחכמתו.

What does Weinberg mean when he speaks of those who oppose the Kovno Rav and try to minimize his importance? Who are these people and what led them to this judgment of the great Kovno Rav? Let me thicken the plot. The late R. Tovia Lasdun wrote to me as follows: “Kovner Rav was a great person, but his views did not always meet the views of the Orthodoxy [!]”

[8] By “Orthodoxy” he meant Lithuanian yeshiva world Orthodoxy. From what we have seen already, namely, his anti-Agudah stand and the other points I noted, one can begin to understand why there would be opposition to the Kovno Rav from yeshiva circles.

R. Jeffrey Woolf recorded the following story about the Kovno Rav. He heard it from an eyewitness and it is very illuminating.

[9]

The pre-war Jewish community of Kovno (Kaunas, today) Lithuania was divided into different components, divided by the Neris River. On the one side was the general community, which was made up of every type of contemporary Jewish religious and cultural population. Indeed, the community was a bit notorious for a lackadaisical form of religiosity. On the other side of the Williampol bridge, was the famous Slabodka Yeshiva, a flagship of the Mussar Movement. As might be expected, relations between the two sectors were often tense. There was a saying attributed to the Alter of Slabodka, R. Nosson Zvi Finkel זצ”ל, that the bridge from Kovno to Slabodko only went one way.

Coping with the myriad of challenges, modernization and secularization in Kovno was its illustrious rabbi, R. Avraham Dov-Bear Kahana-Shapira זצוק”ל, author of the classic collection of responsa and Talmudic essays דבר אברהם, and known more popularly as the ‘Kovner Rov.’ One central concern of his was the alienation of young Kovner Jews from the synagogue. Thus, when the administration of the Choral Synagogue came to him with an intriguing approach to the problem, he jumped at it.

The idea was to have the synagogue’s cantor, the internationally renowned tenor Misha Alexandrovich, offer public concerts that would feature classical חזנות alongside renditions of serene Italian bel canto compositions. The hope was that this type of cultural evening would draw modernizing young Jewish men and women to the synagogue, where they would socialize and (perhaps) find mates.

The first concert was a smashing success and more were planned. Everyone was thrilled, except for the heads of the Slabodka Yeshiva. They turned angrily to the Kovner Rov and demanded that he intervene to stop the concerts. They were indecent, the Rashe Yeshiva objected. The led to fraternization between men and women, and in the synagogue. Worse still, they might corrupt yeshiva students.

The Kovner Rav listened quietly, and then firmly rejected the Yeshiva’s objection. “You are responsible only for your yeshiva,” he asserted. “I am responsible for the spiritual welfare of all of the Jews of Kovno.” The concerts, he declared, would continue.

Returning to R. Elijah Meir Bloch, there is another relevant source and that is found in Chaim Bloch’s Dovev Siftei Yeshenim. (There was no familial relationship between the two Blochs.) As we have discussed numerous times, one can’t believe anything that Bloch wrote, and all of the letters of gedolim he published must be assumed to be forgeries. However, this only applies to the letters he published of deceased individuals, but the letters he published of living figures are indeed authentic. In vol. 1 (1959), p. 392, he published a letter he received in December 1944 from Jacob Rosenheim, the president of World Agudat Israel, then living in New York. Chaim Bloch had written to him asking on what basis the Agudah was now supporting the establishment of a Jewish state. Rosenheim replied that this policy was based on the decision of the “gedolei ha-Torah.” He also mentioned that this support was dependent on two important points. (1) The State had to be run according to Torah, and (2) that the new State would be accepted peacefully by the Arabs. He states that if the Arabs and the world governments agree to the establishment of the State, then there is no prohibition of שלא ימרדו באומות. He also adds that there is no prohibition to establish a state without a Temple, i.e., a State before the coming of the Messiah.

Chaim Bloch strongly rejects Rosenheim’s words, and declares that based upon what Rosenheim writes, there is now no difference between the Agudah and the Mizrachi. This was exactly the claim of the Edah Haredit in Jerusalem, and eventually it and the Agudah would go their separate ways.

The end of Rosenheim’s letter is of interest to us, because after stating that he personally doesn’t believe that in the current (end of 1944) circumstances there is any chance of a Torah state, he adds that R. Eliezer Silver and R. Elijah Meir Bloch do think such a Torah state is possible. I don’t know what this says about the political acumen of Silver

[10] and R. Elijah Meir Bloch, but it shows that R. Bloch had a very optimistic view of the religious development of the future State.

Rosenheim concludes his letter by stating that, unlike Silver and R. Elijah Meir Bloch, “we” (by which he must mean the rest of the Agudah leadership) regard the creation of a State as a real catastrophe. Rosenheim and the others assumed (correctly) that the non-religious would be the majority and that this would create a very difficult circumstance for Orthodox Jews. Their preference was that the land remain under British control, with religious freedom given to all. Rosenheim’s comments today appear surprising, but we must remember that from the perspective of most Agudists, nothing was worse than having a secular “Hebrew State”. Many of them assumed that Zionist control of the Land of Israel would lead to anti-religious measures (which turned out to be correct in some instances). Others might even have believed that the Zionists were to be suspected of wanting to kill the Orthodox!

[11]

Regarding R. Elijah Meir Bloch, let me call attention to one more interesting source. In the volume Yahadut Lita, vol. 2, pp. 234-235, Bloch contributed an article on Agudat Israel, in which, as mentioned, he was very involved. In this article he says the following, which fits in very well with what we learn from Muskin’s essay (I have added the emphasis).

“אגודת ישראל” בליטא, כמו מרכז “יבנה”, התענינו גם בהפצת הדיבור העברית והשתמשו בטקסיהם בדגל הכחול-לבן, שכן סיסמתה של ה”אגודה” בליטא היתה ללחום רק נגד הדברים שהם בניגוד להשקפתה, אבל לא נגד דברים נכונים כשלעצמם, אף שאחרים דוגלים בהם בדרך מנוגדת להשקפת העולם החרדית. סיסמתנו היתה שכל דבר טוב שייך לנו, אף שאחרים הרימוהו על נס, ונקבל את האמת ממי שאמרו. אדרבה, בזה יכולנו לרכוש את דעת-הקהל לצדנו בהיות מאבקנו רק נגד הדברים שהם בניגוד למסורת.

As Bloch says, the approach of the Lithuanian Agudah was not to oppose something just because it was supported by the non-Orthodox. Just because the non-Orthodox spoke in Hebrew in their schools and used the blue and white flag didn’t mean that the Orthodox had to avoid these things. (I have to admit that for Agudah members to use the blue and white flag strikes me as very strange, as from its beginning this was a Zionist flag, not a flag for the Jewish people as a whole.)

In his article, Bloch describes how in the 1930s two hundred Agudah halutzim went on aliyah, after

hakhsharah at Tzeirei Agudah

kibbutzim in Lithuania. Sounding very Zionistic, he notes that among them were those who took part in defense of the yishuv against Arab attacks: ופעלו במסירות למען בנין הארץ.

[12]

In a previous post I asked two quiz questions. No one was able to answer no. 1, which means that the prize will remain for the winner of a future quiz. These were the questions.

1. Tell me the only place in the Shulhan Arukh where R. Joseph Karo mentions a kabbalistic concept? I am referring to an actual concept e.g., Adam Kadmon, Ein Sof, etc.

2. If more than one person answers the above question correctly, the one who answers the following (not related to seforim) will win: Which is the only United States embassy that has a kosher kitchen?

Nachum Lamm and Ari Zivotofsky both got the answer right for no. 2. The embassy is in Prague and the ambassador is Norman L. Eisen. I had the pleasure of davening with him every morning on my trip to Prague last summer. You can read about him

here.

Now let’s turn to the question no. 1. The first thing to note is that there are many halakhot in the

Shulhan Arukh. If R. Joseph Karo was a mystic, as in the title of Werblowsky’s book on him,

[13] one would expect to see evidence of this in the

Shulhan Arukh, and also in the

Beit Yosef. Yet we don’t have this, and references to the Zohar and even basing halakhot on the Zohar have nothing to do with whether one should be thought of as a mystic. By the 16th century the Zohar was a canonical text, so referring to it says nothing about whether one is a mystic, neither then nor today.

However, we know that R. Joseph Karo was a mystic because of his book

Magid Meisharim, which recounts his visions of a heavenly figure, who taught him over many decades.

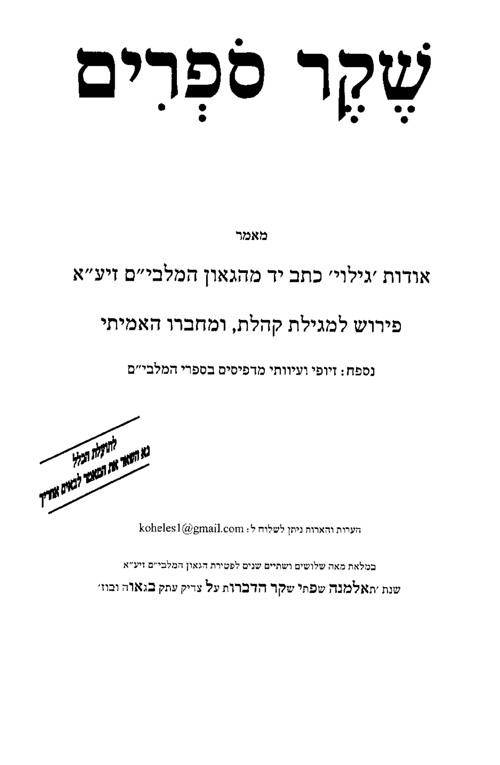

[14] Interestingly, R. Leopold Greenwald denied that Karo wrote this book. He attributes it to an anonymous לץ.

[15] This reminds me of something I noted in an earlier post. See

here where I mention how Abraham Samuel Judah Gestetner denies that R. Jacob Emden wrote

Megilat Sefer, his autobiography. Gestetner claims that it could only have been written by a degenerate maskil! (There is no doubt whatsoever that Emden wrote the work.)

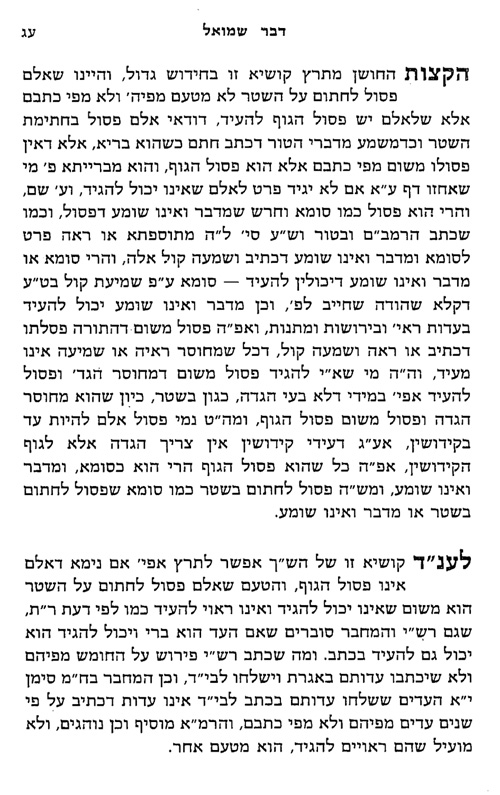

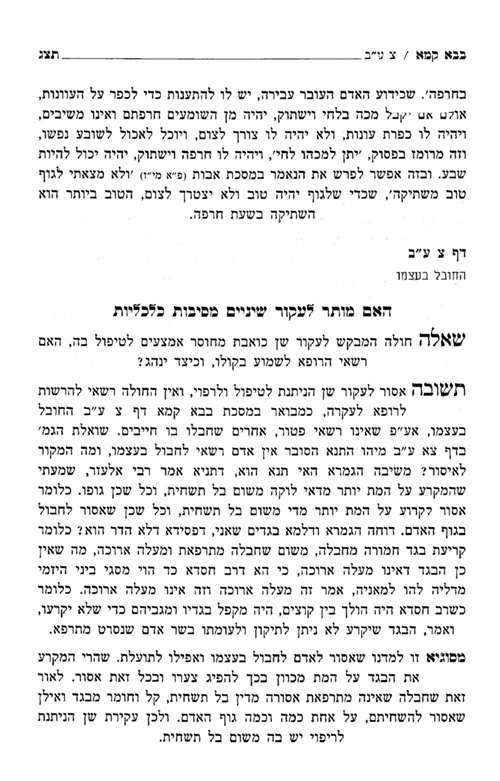

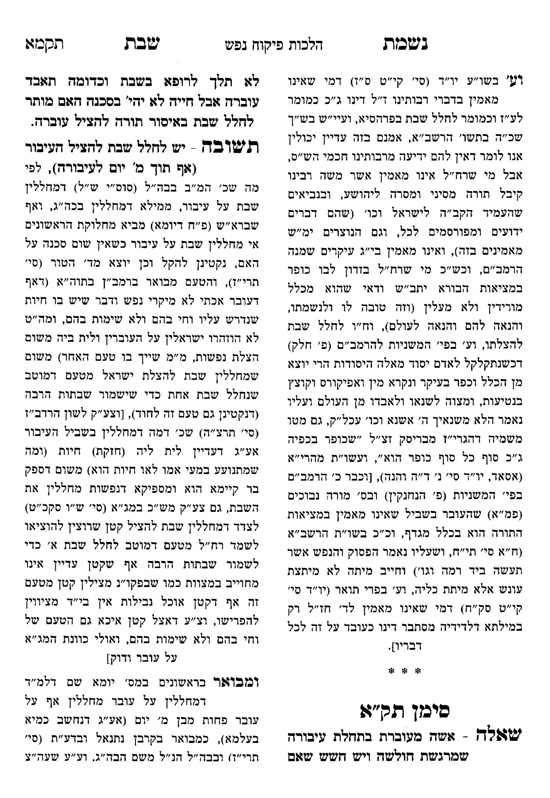

Despite the fact that the Shulhan Arukh does not generally mention kabbalistic ideas, there is one place, and only one place, where he indeed does so. It is in Orah Hayyim 24:5, where he states that the two tzitzit in front have ten knots, which is an allusion to the ten Sefirot:

* * *

I am happy to report that this summer, God willing, I will once again be leading Jewish history-focused tours to Central Europe and Italy. (A trip to Spain is being planned, but will not be ready by the summer.) For information about the trip to Central Europe, please see

here.

Complete information about the Italy trip will will soon be available on the Torah in Motion website.

To be continued

[1] With regard to

Ben-Hur, there are at least eight different Hebrew translations, and they all censor Christian themes in the novel. See Nitsa Ben-Ari, “The Double Conversion of Ben-Hur: A Case of Manipulative Translation,”

Target 12 (2002), pp. 263-302.

[2] Why such

lashon nekiyah? I can think of many more appropriate ways to refer to such criminals.

[3] In the introduction to

Iggerot Moshe, vol. 8, p. 27 (written by the sons and son-in-law), it states that some Satmar hasidim would come to R. Moshe for advice and to receive blessings. But on p. 26 it also records as follows:

[4] His father-in-law, R. Eliezer Gordon, also held both positions, as did his son, R. Avraham Yitzhak Bloch (who was martyred in the Holocaust). Although in the U.S. the Telz yeshiva adopted a very anti-secular studies perspective, this was not the case in Europe. R. Joseph Leib Bloch was very involved with the Yavneh day school system in Lithuania, which incorporated secular studies (and also Tanakh), and in the context of Eastern Europe can be regarded as a form of Modern Orthodox education. It is also significant that in Yavneh schools Hebrew was the language of instruction for all subjects. The preparatory school (mekhinah) of the Telz yeshiva also contained secular studies (which the government insisted on if students wanted to be exempted from the draft).

The graduates of Yavneh attended universities, in particular the University of Kovno, and they had an Orthodox student group named Moriah. By the 1930s, Lithuania had begun to produce an academically trained Orthodox population. Had the Holocaust not intervened, much of Lithuanian Orthodoxy would have come to resemble German Orthodoxy. This is important to realize since people often assume that Bnei Brak and Lakewood are the only authentic continuation of Lithuania, when nothing could be further from the truth. What R. Ruderman attempted to establish in Baltimore was, speaking historically, the true successor of the pre-War Lithuanian Orthodox society’s dominant ethos. (I am speaking of Orthodox society as a whole, not the very small yeshiva population.)

In speaking of R. Joseph Leib Bloch, Dr. Yitzhak Raphael ha-Halevi Etzion, the head of the Yavneh Teacher’s Institute in Telz, writes as follows:

See “Ha-Zerem ha-Hinukhi ‘Yavneh’ be-Lita,” Yahadut Lita, vol. 2, pp. 160-165.

R. Shlomo Carlebach wrote as follows, after describing the creation of the Kovno Gymnasium, a Torah im Derekh Eretz school established by R. Joseph Zvi Carlebach (Ish Yehudi: The Life and the Legacy of a Torah Great, Rav Joseph Tzvi Carlebach (Brooklyn, 2008), pp. 74, 76):

The Kovno Gymnasium left a deep impression upon the Lithuanian Torah leaders, who could not help but notice the enthusiastic response to the Torah im Derech Eretz educational approach on the part of students and parents. They realized that this approach caused no compromise in Yirat Shamayim. The enormous upheaval in the political and social structure of Jewish society throughout the land, in the aftermath of war, threatened the stability and loyalty of Jewish youth. Under those circumstances, these Torah leaders felt an urgent need to introduce a similar educational program, on a broad scale, by reorganizing existing schools and establishing new ones, where subjects in Derech Eretz would be taught alongside Limuday Kodesh.

At the behest of the Telzer Rav, Rav Joseph Leib Bloch, a world-renowned gaon and Rosh Yeshivah of the equally renowned Telzer Yeshivah, Dr. [Leo] Deutschlaender, director and guiding spirit of the Keren Hatorah Central Office in Vienna, was summoned to Kovno to organize, in consultation with the Rav [Joseph Zvi Carlebach] such an educational system, to be called Yavneh. . . . At its conclusion, he published a summary of the “Yavneh educational project” in the “Israelit”. He reported that separate teachers’ seminaries for men and women had been established in Kovno, in addition to “gymnasium-style high schools in Telz, Kovno, and Ponevesh, and approximately 100 elementary schools spread throughout the land.”

It is interesting that when the late, unlamented, Jewish Observer published a review of this book by R. Yosef Gavriel Bechhofer, the editor felt constrained to insert the following “clarification,” knowing that its readers would be shocked to learn that Lithuanian Torah Jewry was not an enlarged version of Lakewood.

The best part of this “clarification” is the final sentence. I wonder, why does such a careful scholar and talmid hakham as Rabbi Carlebach need to have his book vetted by “gedolei Torah and roshei yeshivos”, who for all their talmudic learning are not known as experts in historical matters? Since the Agudah gedolei Torah and roshei yeshivot are prepared to cover up historical truths (as seen in their signing on to the ban of Making of a Godol), why in this case did they agree to allow the masses to learn what really was going on in Lithuania? Is it because they too feel the need to change the direction of American haredi Orthodoxy to a more secular studies friendly perspective, and this could help set the stage for this?

Returning to Telz, the question remains why Telz in Cleveland adopted such an extremely negative outlook regarding secular studies? Maybe a reader can offer some insight. R. Rakeffet has reported that R. Samuel Volk of YU, who was himself an old Telzer, commented that Telz in Cleveland distorted what Telz in Europe was about.

An interesting story about the Cleveland Telz was told to me by Rabbi M.C., a Cleveland native (and YU musmach). He was at the Telz high school and upon graduating decided to go to YU. R. Mordechai Gifter summoned M.C.’s mother and told her that if her son goes to YU, within a few months he will no longer be religious. She then angrily demanded that R. Gifter return to her all the years of tuition she had paid. She said: “If you tell me that after all the years my son has studied here, it will only take a few months at YU before he becomes non-religious, then the education you offer must be pretty lousy, and I want my money back!”

R. Dov Lior recalls that R. Zvi Yehudah Kook had a similar reaction when at a meeting of roshei reshiva with Minister of Defense Shimon Peres a haredi rosh yeshiva claimed that putting yeshiva students in the army could lead to them becoming non-religious (Hilah Wolberstein, Mashmia Yeshuah [Merkaz Shapira, 2010], p. 296):

הרכין הרב צבי יהודה את ראשו כולו בוש ונכלם. הרי צבא ישראל, צבאנו הוא, ולא צבא הפריץ הנוכרי, ולכן חובה עלינו להשתתף בו. זאת ועוד, האם המטען שהבחורים קיבלו בישיבות אינו חזק דיו שיש לחשוש כל כך לקלקולם?

[5] See his

Shiurei Da’at (Tel Aviv, 1956), vol. 3, p. 65 (in his shiur “Dor Haflagah”), where we see that he was also opposed to messianic Zionism, so it appears that he didn’t really understand R. Kook’s ideology.

[6] In all the discussions recently about the success of Daf Yomi, I didn’t see anyone note that one of the reasons this success is so surprising is that the whole notion of Daf Yomi goes against what for many years was the outlook of the rabbinic elite. The Shakh,

Yoreh Deah 246:5, quoting the

Derishah, states that laypeople should not only study Talmud but also halakhah, which he thinks should be their major focus as practical halakhah is שורש ועיקר לתורתינו. It is not hard to understand the point that since a layperson’s time is limited, he will get more out of his learning by focusing on practical material. If, for example, one has an hour a day to learn, what makes more sense: to go through hilkhot Shabbat or to study Talmud? While people today prefer Talmud, the Shakh prefers halakhah, and I don’t know of any rabbinic figures in years past who disagreed with the Shakh. This Shakh is also mentioned in the introduction to the

Mishnah Berurah. While it is obvious that one who has time to learn both Talmud and practical halakhah is in the ideal circumstance, how did we get to the situation where those whose time is limited are now encouraged to focus on Talmud? The credit (or blame, depending on your outlook) for this development can, I think, be laid at Artscroll’s door, for Artscroll made learning Talmud exciting for the masses, in a way that halakhah is not, and maybe can never be.

Daf Yomi is so revolutionary precisely due to its democratic ethos, that everyone is welcome to study that which used to be the preserve of only the elites. Much like American universities opened up higher learning to the masses, and created a situation where for the first time in history texts such as Plato and Aristotle were now taught (or spoon-fed) to all, so too, for he first time in history, Daf Yomi allowed Talmud to become a product of mass consumption.

[7] See e.g.. R. Eleazar Shakh,

Mikhtavim u-Ma’amarim, vols. 1-2, no. 111.

[8] Rabbi Rakeffet has reported the following story that he was told by R. Bernard Revel’s widow, Sarah. When the Kovno Rav was in New York he was at some gathering with Revel. Revel told him that he had to excuse himself as he had yahrzeit and had to go recite kaddish at a minyan, The Kovno Rav replied: “You also believe in that?” The implication was that the notion of saying kaddish on a yahrzeit was folk religion, not something that Torah scholars take seriously. Mrs. Revel was shocked when she heard the comment, but Rakeffet is probably correct that this was an example of Lithuanian rabbinic humor.

[10] I heard from a Holocaust survivor that in 1946 Silver came to Kielce. Dressed in a military uniform, he gave a speech telling the people to remain in Poland in order to rebuild Jewish life there. The man who told me this thought that Silver’s speech was directed against the Mizrachi. (Silver was in Poland on July 4, 1946, the date of the infamous Kielce pogrom, yet I don’t know if his visit to Kielce was before or after the pogrom.) Silver was not a chaplain, but rather an emissary of Agudat ha-Rabbanim and Vaad Hatzalah. “The American government agreed to Silver’s wearing an Army uniform so its insignias would add to his protection in areas where anti-Semitism was still rife.”Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff,

The Silver Era (Jerusalem/New York, 2000), p. 228.

[11] It has been reported that R. Moshe Sternbuch claims that he was told by R. Velvel Soloveitchik that his father, R. Hayyim, once expressed fear of not being left alone with a religious Zionist. He was worried that the latter would kill him, since the Zionists are suspected of

shefihut damim. See

Mishkenot ha-Ro’im, vol.1, p. 271, quoting

Om Ani Homah, Sivan 5732. (I don’t know if Sternbuch is being quoted accurately, but I can’t imagine that R. Hayyim would ever have said this about a religious Zionist. A number of his own students and relatives were religious Zionists!). The exact same fear was, according to Moshe Blau, expressed by R. Joseph Rozin, the Rogochover:

הלא הם [הציונים] חשודים על הכל, הם חשודים גם על שפיכות דמים

See Yair Borochov, Ha-Rogochovi p. 70. (After the killing of Jacob de Haan, this viewpoint was given some basis.) See ibid., where Blau also quotes the Rogochover as saying that the reason he stopped publicizing his anti-Zionist views was because he was asked to do so by his daughter, who was married to R. Yisrael Abba Citron, the rav of Petah Tikvah. Citron was a Mizrachi supporter and it was creating problems for him that his father-in-law was attacking the Zionist movement. Regarding Citron, see the fascinating book-length biography of him that appears at the beginning of his volume of hiddushim, published in 2010.

[12] As Eliezer Brodt noted in his last post, Bloch’s son, R. Yosef Zalman Bloch,

Be-Emunah Shelemah (Monsey, 2012), pp. 115-116, quotes a strongly anti-Zionist and anti-Mizrachi letter of the elder Bloch, attempting to leave the impression that when it came to this issue his father had a completely negative attitude. However, as we have seen, the truth is more complicated. In general, Y.Z. Bloch’s book is quite a strange mix of wide learning combined with unbelievable nonsense, a point alluded to much more gently by Brodt. On the very page that he quotes his father’s view of Zionism, he tells us that one who does not believe that God’s individual providence encompasses everything in the world, even the animals, insects, falling leaves, etc. הרי הוא כופר בעיקר, ואין לו חלק לעוה”ב. He says that the sages in earlier times who didn’t have this perspective were tzadikim and they are at present in Olam ha-Ba, but today, after the matter has been “decided” by the Masorah, holding such a position is heretical. Leaving aside the question as to why he feels he is a prophet and can in bombastic fashion declare who has lost his share in the World to Come (something he is fond of doing in this book), does he not realize how many great Torah scholars from even recent generations he has (inadvertently?) condemned as heretics?

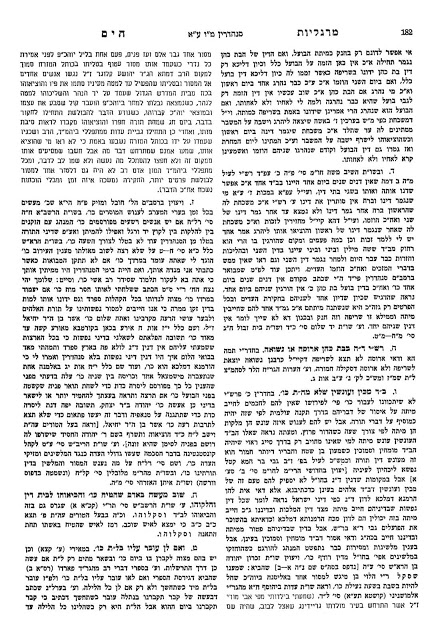

This is all so obvious to me that I don’t see any need to cite “authorities.” But for those who want this, let me offer the following. A few years ago, an author writing in Mishpahah asserted that one who believes that animals are not subject to individual providence, it is like he is “eating fowl with milk” (which is a lot less severe than Bloch’s judgment that such a person is a heretic with no share in the World to Come). R. Meir Mazuz, Or Torah, Tamuz 5769, pp. 867-868, responded to this strange assertion by citing many authorities who indeed held this position, and he mentions nothing about it being “rejected by the Masorah.” He concludes:

A large section of Bloch’s book is designed to show that the only acceptable Torah belief is that the sun, planets, and stars revolve around the earth. As for Copernicus, he refers to him as קופירניקוס הרשע שר”י (p. 351 n. 36).

Among his nuggets of wisdom is that astronomy is the most heretical, and anti-Jewish, of all the sciences. P. 387 n. 1:

Since, as he states, these scientists are not only heretics but also stupid fools, one can only wonder how they were able to figure out how to put a man on the moon.

On p. 331 he refers to the view of R. Jacob Kamenetsky (without mentioning him by name) that the first four chapters of Hilkhot Yesodei ha-Torah are not to be regarded as Torah but as פילוסופיא בעלמא. See Emet le-Yaakov (New York, 1998), pp. 15-16. Bloch sees this as absolute heresy, and he quotes R. Yehudah Segal of Manchester as saying that even if the Hatam Sofer or the Noda bi-Yehudah said this, we would not accept what they said, and would be forced to reinterpret their words. Bloch quotes this approvingly, and this illustrates the problem. He is so locked into his dogmatic assumptions that his mind is closed and doesn’t want to be confused with the facts.. If most people were shown an explicit text of the Hatam Sofer or Noda bi-Yehudah that diverges from their dogmatic assumption, they would conclude that their assumption of what is “acceptable” needs to be revised. But Bloch refuses to even acknowledge the possibility that people greater than him might have a different perspective on what constitute the fundamentals of faith.

Bloch advocates this approach even when it comes to the rishonim (p. 117):

On p. 336 Bloch goes further than merely rejecting the Copernican outlook that earth revolves around the sun. He also denies that the earth rotates on its axis. According to him, it is a Torah truth that the earth stands still: שהארץ עומדת על עמדה ואינה זזה כלל.

The absolute craziest thing he says, in a book filled with absurdities, is that the sun, moon, and all the stars [!] revolve around the earth every twenty-four hours!:

I guess it is a neat trick that stars so many light years away (i.e., trillions of miles away) are able to circle earth each day. (Our galaxy alone has hundreds of billions of stars.) But seriously, is one supposed to laugh or cry when reading this? How should one relate to a rabbi who so dishonors the Torah by claiming that this is Torah truth, and a required belief of any religious Jew?

On p. 289 Bloch writes:

Everything in this sentence is incorrect, and is contradicted by numerous explicit statements in rishonim and aharonim.

[13] Joseph Karo: Lawyer and Mystic (Oxford, 1962)

[14] Regarding why R. Joseph Karo doesn’t mention the

maggid in his halakhic writings, see Eliezer Brodt,

Likutei Eliezer (Jerusalem, 2010), pp. 106ff. As usual, Brodt shows incredible erudition.

[15] Kol Bo al Avelut (Brooklyn, 1951), vol. 2, p. 31, in the note. Greenwald elaborates on this position in

Ha-Rav R. Yosef Karo (New York, 1953), ch. 8.