Everything is Illuminated: Mining the Art of Illustrated Haggadah Manuscripts for Meaning

We have discussed haggadah illustrations in the past (see the links at the end of this post) and we wanted to expand and update upon that discussion for this year. In this post we focus on Hebrew illuminated haggadah manuscripts, and in the follow-up post will turn our attention to printed illustrated haggadot.

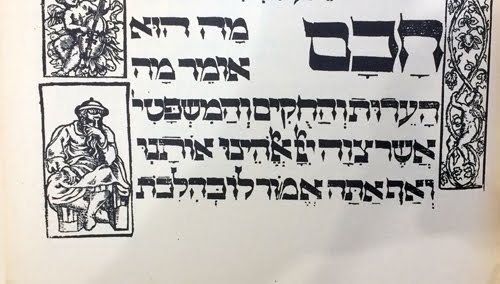

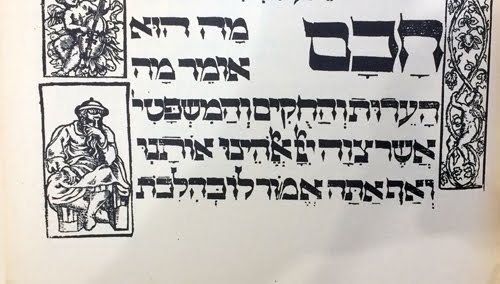

While there is not as large of a body of Jewish art as that of art in general, historically Jews have appreciated the visual arts early in their evolution into a nation. Aside from the biblical forms, we have evidence of art dating to the second century of the common era in the well-known frescos at the Dura-Europos synagogue.[1] But, such appreciation was not limited to second century Palestinian Jews, as evidenced from the discussion below, this appreciation continued, almost unabated, until the modern period. It was not just the artist class or wealthy acculturated Jews that were exposed to and admired this medium. For example, in the 1560 Mantua haggadah, one of the more important printed illustrated haggadot, the wise son appears to be modeled after Michelangelo’s Jeremiah in the Sistine Chapel (view it here:

link).

Lest one think that it is highly unlikely that a 16th century Italian Jew would have even entered the chapel, let alone been familiar with this painting, a contemporaneous account of Jewish art appreciation disabuses those assumptions. Specifically, Giorgi Vasari, the 16th century artist and art historian, in his Lives of Excellent Painters (first published in 1560), records regarding Michelangelo’s statute of Moses – that is a full statute depicting the human form and was placed in the church of San Pietro in Rome – that “the Jews [go] in crowds, both men and women, every Saturday, like flocks of starlings, to visit and adore the statue.” That is, the Sabbath afternoon activity was to go to church to admire the statute of Moses, that is more famous for having horns than its Jewish visitors.[2]

Hebrew Manuscripts Background

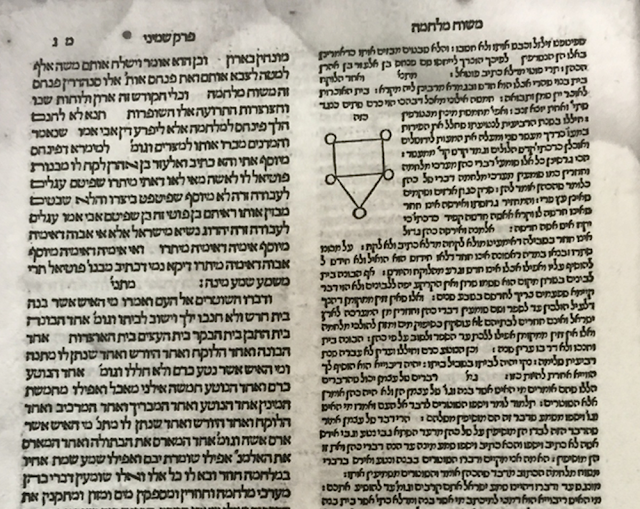

A brief background regarding Hebrew manuscripts before delving into the illuminated haggadah manuscripts. Details regarding manuscripts, the name of the copyist, the date, and the place where the manuscript was written, were supplied not at the beginning of the book – as is the convention with printed books and title pages – instead in manuscripts this information is provided at the end. For this reason, the scribe’s note containing the information was called a colophon – from the Greek word

kolofon, meaning “summit” or “final point.”[3]

Number of Hebrew mss.

A cautious guess of the number of extant Hebrew manuscripts in existence is between 60,000 -70,000 “but no more than 30-40 thousand of them predate the middle of the sixteenth century.”[4] Of the 2-3 hundred thousand Hebrew manuscripts presumed in existence in Europe at the beginning of the fourteenth century, probably no more than four to five thousand are extant today, possibly even less. “From the tenth century (before which information is very scarce) to 1490 (when the influence of printing books began to be felt)” there are an estimated one million manuscripts, meaning, “that 95 per cent of manuscripts have disappeared.”[5] In addition, the early printed books – incunabula – had similar survival rates.

The dearth of manuscripts has left a significant hole in our knowledge of major Jewish texts. For example, there is only one complete manuscript of the Palestinian Talmud (1289) and two partial manuscripts. The Babylonian Talmud fared slightly better, with one complete manuscript (1342) and 63 partial manuscripts in libraries, with only 14 dating from the 12th & 13th centuries.[6]

One of the partial TPs is known as the Vatican Codex 133 – and worth mentioning is the Vatican and its role regarding Hebrew manuscripts. While there is no doubt that the Church had a significant hand in reducing the number of manuscripts – in reality the destruction of Hebrew manuscripts was the work of the Jesuits and not the Roman Catholic Church. Indeed, the Church confiscated and, thus in some instances preserved Hebrew manuscripts. Consequently, we have a number of important Jewish texts that survive in the Vatican library. Today, many of these manuscripts have been published. The incomplete manuscript of the TP is but one example. Additionally, regarding the use of (rather than just reprinting) the Vatican library, for at least late 19th century, Jews had access to the library. For example, R. Raphael Nathan Rabinowitz, who authored a monumental work on Talmudic variants provides that “I prayed to God to permit me entrance to the Vatican library to record variant readings” his prayer was answered, and he received permission not only to use it during regular hours but “even on days that it was closed due to Christian holidays, when the library was closed to all, and even more so Jews.”[7] In total he spent close to 9 months in the library. In addition, Rabbi Rabinowitz’s presence and special status at the Vatican library was instrumental for the editing of the Vilna Talmud, where he secured permission for the Romm-employed copyists to work with manuscripts of the commentary of Rabbenu Hananel, even though they arrived in Rome during the summer season when the library was closed.

Of the estimated one million Hebrew manuscripts from the 10th century until 1490, approximately 5% have survived. As mentioned, religious persecution was one reason, but the main reasons are (1) deterioration from use, (2) accidents, and (3) reuse. The first two are self-explanatory, the third requires a bit of explanation. From the times that manuscripts were written on papyrus, unwanted manuscripts were scraped or washed and then reused. (This papyrus recycling was not confined to reusing for books, papyrus was used from wrapping mummies, burned for its aroma, and used, according to Apices, to wrap meat for cooking). Similarly, leather and parchment were recycled, in the more egregious examples for shoe leather but in many cases for book bindings. The latter reuse would be critical to the survival of numerous Hebrew manuscripts which have now been reclaimed from bindings. It is estimated that there are 85,000 such binding fragments. “The commonest use of written folios, however, was in bindings, whether for binding strips, end papers, or covers.”[8]

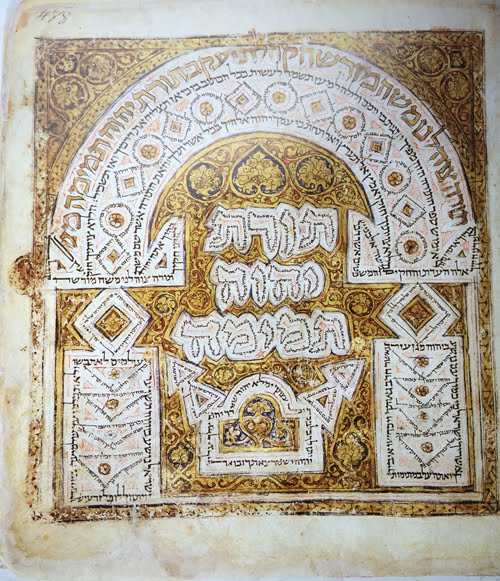

Illuminated Hebrew Manuscripts

The “earliest examples of Jewish book illumination are tenth-and eleventh-century Bible codices written in the Orient or Near East. The illuminations are not figurative but consist of a number of decorative carpet pages adorned with abstract geometric or micrographic designs preceding or following the Biblical text.”[9] While these early illuminated manuscripts did not contain human figures, they did contain the first iterations of something unique to Jewish manuscripts, “one form of manuscript depiction unique to Jewish manuscripts is micrography with the earliest examples of this art may be found in the tenth-century Bibles written in the Orient.”[10] A beautiful example of this art can be seen in the carpet pages for the Leningrad Codex.

Similar non-representational geometric art was incorporated into Islamic art to avoid graphic representation. Consequently, symmetrical forms were created which

required advances in math theory to accommodate the ever more complex art.

Hebrew manuscripts did not adopt the Islamic convention – for the most part – and the earliest illustrations of human figures appear in Franco-Ashkenazic manuscripts – bibles – of the thirteenth century.

The earliest extant illustrated haggadah[11] is what is known as the Birds’ Head Haggadah dated to the early 1300s. The moniker “Birds’ Head” comes from the fact that the illustrator used birds heads/griffins in place of human heads. This manuscript is not the only Jewish manuscript to use zoophilic (the combination of man and beast) images. Zoophilic images can be found in a variety of contexts in Jewish manuscripts. For example, in the manuscript known as Tripartite Machzor, men are drawn normally while the women are drawn with animal heads.[12] The name of this Machzor comes from the random fact that the manuscript was split up into three. At times manuscripts are titled by location (Leipzig Mahzor), history (tripartite) or owner. In one example, the “Murphy Haggadah” “ suffered a fate all too common to many Hebrew texts. Before the Second World War the manuscript belonged to Baron Edmond de Rothschild. During the war it was stolen and sold to an American, F.T. Murphy, who bequeathed it to Yale University, his alma matter. For years it was known as the “Murphy Haggadah” until, in 1980, a Yale scholar, Prof. J. Marrow, identified as belonging to the Rothschilds. The manuscript was returned to the Rothschild family and presented by the Baroness Dorothy to the Jewish National Library.[13]

When it comes to the Birds’ Head manuscript, a variety of reasons have been offered for its imagery, running the gamut from halachik concerns to the rather incredible notion that the images are actually anti-Semitic with a bird’s beak standing in for the Jewish nose trope and the claim that the ears on the “birds” are reminiscent of pigs’ ears. Generally, those claiming halackhic, or more particular pietistic reasons, do so because they are unable “to conceive of such a bizarre and fanciful treatment of the human image as emerging from anywhere other than the twisted and febrile imagination of religious fanatics.”[14] But, in reality the use of bird’s head in lieu of human “reflects a liberal halakhic position rather than an extreme one.”[15] The camp of Yehuda ha–Hassid would ban all human, animal and celestial depictions, a more liberal position from this perspective permits animal images. And, while that position doesn’t explicitly permit a depiction half-animal half-human, the zoophilic images appear to show they were allowed, as the illuminator and owner of the Birds Head Haggadah agreed with that position.

Aside from halakha, and the meaning or lack thereof behind “birds”, a close examination how the illuminator used this convention yields surprising nuance and commentary.

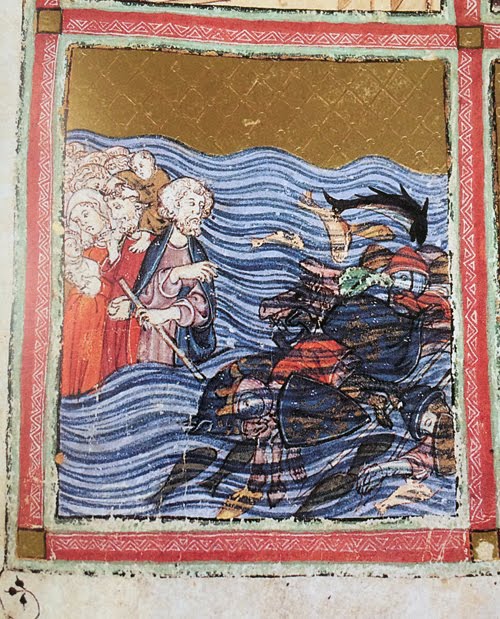

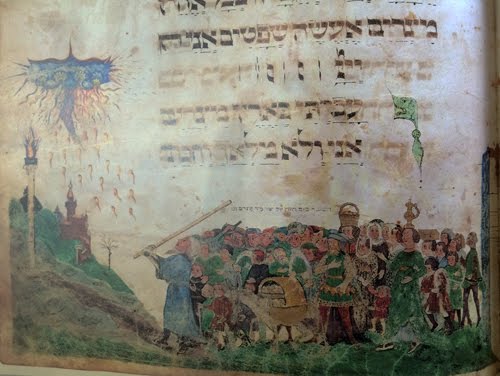

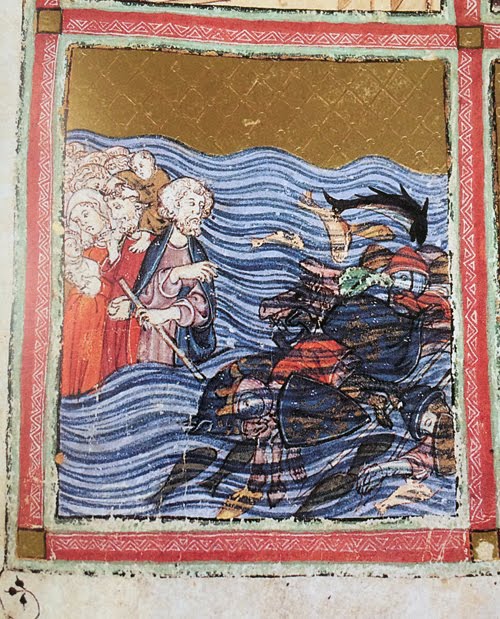

While most of the images carry a bird’s head, there are a few exceptions. Most notably, non-Jews, both corporeal and spiritual do not. Instead, non-Jewish humans as well as angels have blank circles instead of faces. But, there is one scene that poses a problem. One illustration shows the Jews fleeing Egypt (all with birds’ heads), being pursued by Pharaoh and his army. Pharaoh and his army are depicted faceless.

But, unlike the rest of the figures in Pharaoh’s army, two figures appear with birds’ heads. Some write this off to carelessness on the illustrator’s part. Epstein, who credits his (then) ten-year old son for a novel explanation, offers that these two figures are Datan and Aviram, two prominent members of the erev rav, those Jews who elected to remain behind. Indeed, they are brandishing whips indicative of their role as nogsim (Jewish taskmasters, or the precursor to Jewish Sonderkommando). While the illustrator included them with the Egyptians, he still allowed them to remain with their “Jewish” bird’s head. This is a powerful idea regarding the idea of sin, and specifically, the Jewish view that even when a Jew sins, they still retain their Jewish identity – their “birds head.” Sin, and including sinners as Jews, are motifs that are highlighted on Pesach with the mention of the wicked son and perhaps is also indicated with this illustration. The illustrator could have left Datan and Aviram out entirely or decided to mark them some other way rather than the Birds’ head. Thus, utilizing this explanation allows for the illustrator to enable a broader discussion about not only the exodus and the Egyptian army’s chase, but expands the discussion to sin, repentance, Jewish identity, inclusiveness and exclusiveness and other related themes.[16]

Once we have identified the Jews within the haggadah, we need to discuss another nuance in their depiction. The full dress of the adult male bird is one with a beard and a “Jewish hat,”

pieus conutus – a peaked hat, or the Judenhut. Children and young servants are bareheaded. But, there are three other instances of bareheadness that are worthy of discussion. (1) Joseph in Egypt, (2) the Jews in Egypt and (3) Datan and Aviram. The similarity between all three is that each depicts a distance from god or Jewish identity. Joseph, unrecognizable to his brothers, a stranger in a strange land, and while inwardly a Jew, externally that was not the case.

The Jews in Egypt had sunk to the deepest depths on impurity, far from God. Finally, as we discussed previously, Datan and Aviram are also removed from god and the Jewish people. Again, the illustrator is depicting Jews – they all have the griffin heads – but they are distinct in their interaction with god and the Jewish people.[17]

Using this interpretation of the griffin images, yields yet another subtle point regarding inclusion, and also injects some humor into the haggadah. The

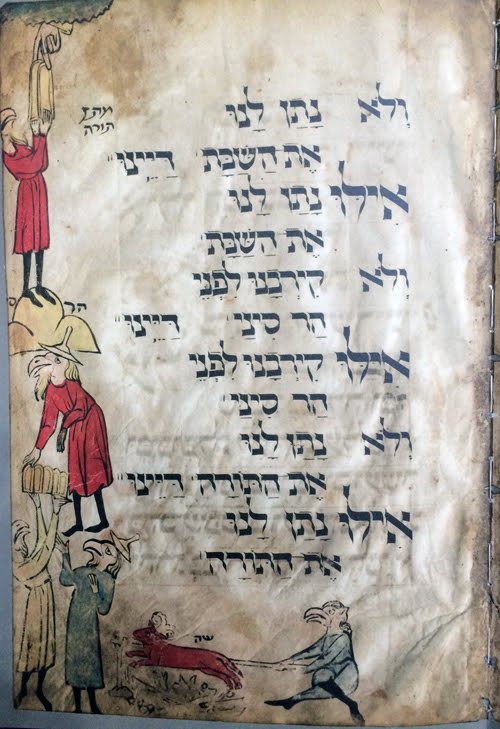

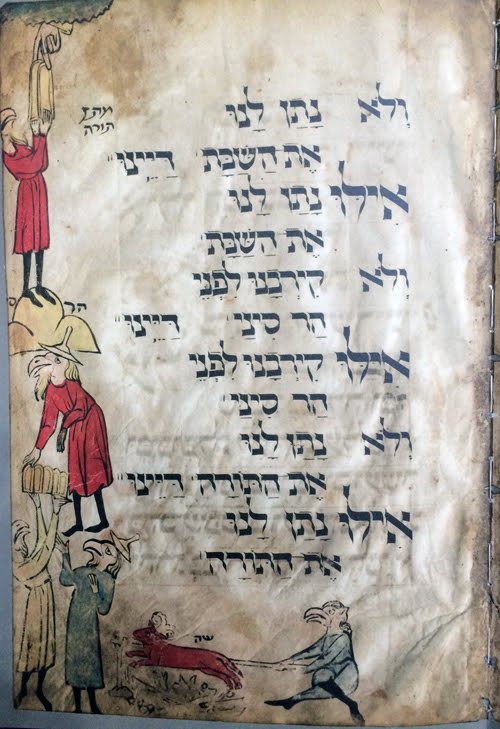

dayenu panel has splitting of the sea, the manna and the giving of the Torah. The middle panel is less clear. Some posit that it is the Jews celebrating at the sea, but there is no indication of that because in most manuscripts, that includes Miriam, and the Egyptians drowning, not just five random images.

Instead, it appears that the person to the left is speaking (his hand is over his heart a medieval convention to indicate speech), and they are approaching the older figure on the left. All are griffin headed and Judenhut attired – so Jews and regular ones. Between the splitting of the sea and the manna and quails the Jews complained to Moses. Its possible that this is what is being depicted here, the complaining Jews, and the illustration serves as a testament to God’s patience and divine plan, the theme of dayenu, that even though we complained and did X, God still brought the manna, quail and Torah.[18]

If these are in fact the complainers, we can theorize about another detail of the image. Above the figure at the left and the right, is faint cursive (enhanced here for visibility as much as possible) that reads: “

Dass ist der Meirer (this is Meir)

Dass ist der Eisik (this is Issac).”[19] Thus Meir and Issac are being chided – but not kicked out – for complaining too much (rather than representing an unclear image of the Jews celebrating at the sea or just evidencing poor dancing).

Continuing through the

dayenu we get to the giving of the Torah, and again, the nuance of the illustrator is apparent

.

Two tablets were given at Sinai, but the actual Pentateuch is comprised of 5 books. Thus, to capture that the 5 are a continuity of the two, as they are transmitted down, they transform into five tablets. What about the ram/lamb at the bottom? Some have suggested that it is the Golden Calf. But it is unlikely that such a negative incident would be included. Instead, assuming that continuity or tradition is the theme, this lamb is representative of pesah dorot that is an unbroken tradition back to Sinai and unconnected with the Christian idea of Jesus as a stand in for the lamb. Immediately prior to dayenu we have the Pesach mitzrayim with the figure’s cloak blowing back due to the haste.

Thus, the dayenu is bracketed by the historic Pesach and the modern one – all part of the same tradition. [20]

It is worth mentioning that the Birds’ Head Haggadah is currently in the news. An item recently appeared about how the heirs of Ludwig Marum and his wife Johanna Benedikt, the owners of the haggadah prior to the Nazi era, are pressing the Israel Museum to recognize their family’s title, and pay them a large sum of money (but only a fraction of its estimated value). The Israel Museum acquired the haggadah for $600 from a German Jewish refugee in 1946. (

link).

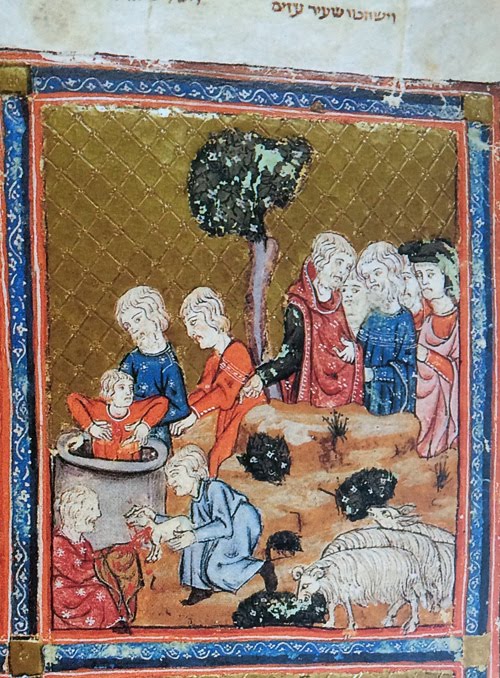

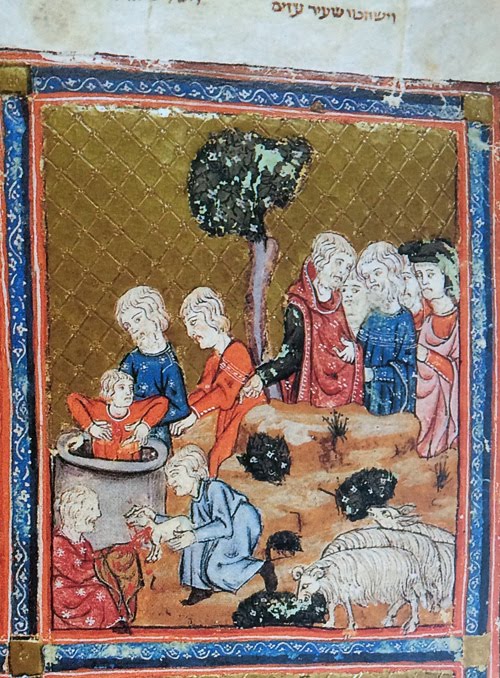

Turning to Spain, one of the most beautiful illuminated haggadot is the “Golden Haggadah.” Just as the Ashkenazi Bird’s Head has depth to the illustrations, the Golden Haggadah can be mined for similar purpose. Each folio is comprised of four panels. And while they appear to simply depict the biblical narrative, they are so much more.

In an early panel we have Nimrod throwing Abraham into the fire and later Pharaoh throwing the males in the Nile, both Nimrod and Pharaoh are similarly depicted, on the throne, with a pointed finger indicating their equivalence in denying god.

The folio showing the Joseph story has the brothers pointing in the same manner as Pharaoh and Nimrod – the illustrator showing his disdain for the mistreatment and betrayal and equating it with the others.

But, that is not all. Counting the panels there are 9 between Nimrod and Joseph and 9 between Joseph and Pharaoh. Taken together, these illustrations “renders an implicit critique of the attitude of that Jewish history is nothing but an endless stream of persecution of innocent Israel by the bloodthirsty gentiles. Yes, it is acknowledged, these gentile kinds might behave villainously in their persecution of Jews. But groundless hatred between brother and brother is on par with such terrible deeds, and sometimes sinat hinam can precipitated treachery as destructive as persecution by inveterate enemies.”[21]

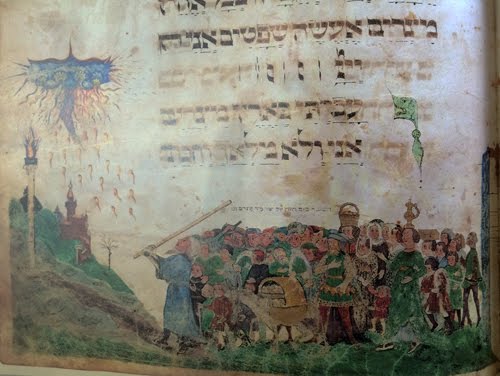

One other striking feature of the Golden Haggadah is the inclusion of women. There are no fewer than 46 prominent depictions of women in the haggadah. Indeed, one reading of the exodus scene has a woman with a baby at the forefront leading the Jews out of Egypt behind Moses.

This may be a reference to the midrash that “in the merit of the righteous women the Jews were redeemed.”[22] The difference in the exodus scene is particularly striking if one compares it to the Ashkenaz Haggadah – Moses clearly at the front, and the most prominent woman in the back.

Of course, it is completely appropriate for the inclusion of women in the haggadah as women and men are equally obligated to participate in the seder. Another example of the prominence that woman play in the Golden Haggadah iconography is the scene of Miriam singing includes the largest images in the haggadah, the women occupying the full panel. We don’t know why the illustrator chose to highlight women – was it for a patron or at a specific request.[23]

The Golden Haggadah is not the only manuscript that includes women in a prominent role in the illustrations. The Darmstadt Haggadah includes two well-known illuminations that place woman at the center. The illuminations adoring other Darmstadt serve a different purpose than the Golden or Birds’ Head, they are purely aesthetic.[24] Thus, the inclusion of women may not be linked to anything in particular. At the same time, it is important to note that in terms of reception, that is, how the reader viewed it, the focus on women was not cause for consternation. One other note regarding the haggadah, the last panel is a depiction fountain of youth. Note that men and woman are bathing – nude – together, which seems odd to a modern viewer (and, again, apparently did not to the then contemporary reader). And, while admittedly not exactly the same, the 14th century R. Samuel ben Baruch of Bamberg (a teacher of R. Meir of Rothenberg) permitted a non-Jewish woman to bath a man so long as it was in public to reduce the likelihood of anything untoward occurring.[25]

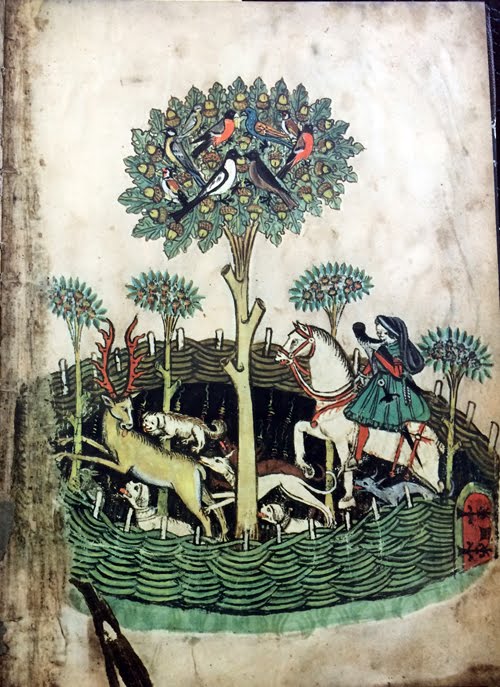

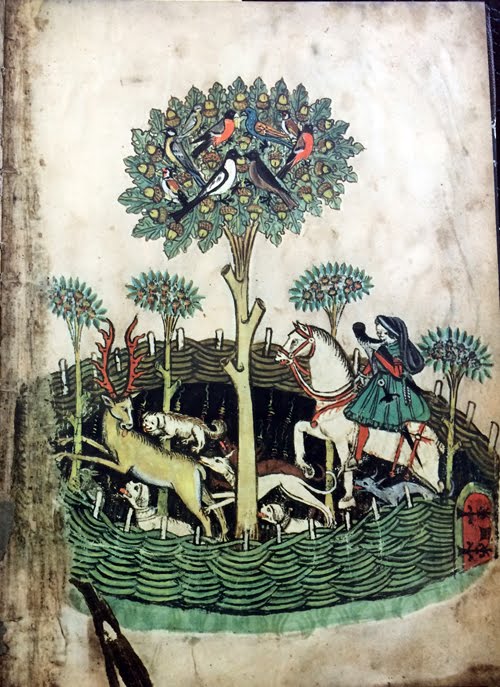

Before we leave the Darmstadt Haggadah, we need to examine the panel facing the Fountain of Youth. This panel depicts a deer hunt.

As mentioned above, this image is not connected to the text and instead is solely for aesthetic purposes. The hunting motif is common in many medieval manuscripts, and in some a unicorn is substituted for a deer. While the unicorn has Christological meaning, on some occasions it also appears in Hebrew manuscripts.[26]

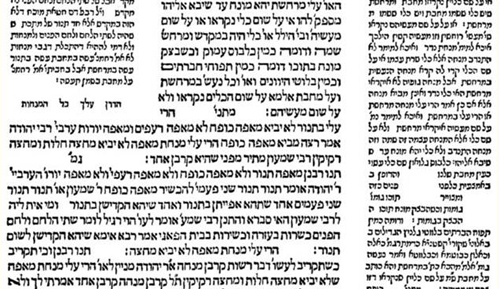

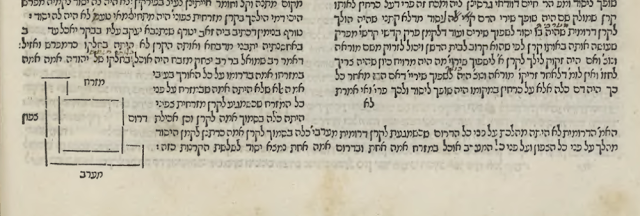

While the use of the hunting scene in the Darmstadt Haggadah was unconnected to the haggadah, in others it was deployed for substantive purpose.[27] [As an aside, it is possible that Jews participated, possibly Rabbenu Tam, in hunting, or at least its falconry form.[28]] As is well-known, the inclusion of the hare hunt is to conjure the Talmudic mnemonic regarding the appropriate sequence over the wine, candle, and the other required blessings, or YaKeNHaZ. “To Ashkenazic Jews, YaKeNHaZ sounded like the German Jagen-has, ‘hare hunt,’ which thereby came to be illustrated as such in the Haggadah.”[29]

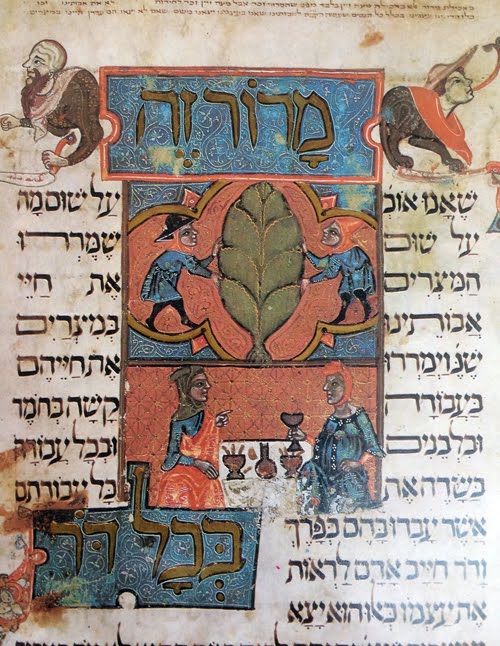

Generally, Jews seem to have issues with botany. We struggle to identify which of the handful of fruits and vegetables mention in the Bible and Talmud. But on Passover, the marror an undefined term, proves particularly illusory. Today, there is no consistency regarding what is used for marror with it running the gamut from iceberg lettuce to horseradish root. While we may not be able to identify it with specificity, we know what its supposed to taste like – bitter. Manuscripts may provide some direction here. There are two depictions in illuminated haggadot. One of a leafy green, found in numerous examples, from a fragment from the Cairo Geniza to the Birds’ Head, and that of an artichoke.[30] If it is a leafy green, it must be a bitter one – and that changes based upon time, place and palate. For example, 30 years ago romaine lettuce was only the bitter lettuce widely available. But, among lettuces, it is far from bitter, and today, there are a variety of truly bitter lettuces available, arugula, mustard greens, dandelion, mesclun, etc. Another leafy and very bitter option that is found in illuminated haggadot is the artichoke. The artichoke is extremely bitter without proper preparation. Indeed, from just touching the leaves and putting them in your mouth you can taste the bitterness. The Sarajevo Haggadah and brother to the Rylands both have artichokes.

The association of the artichoke with Passover is more obvious when one accounts for Italian culinary history. Specifically, artichokes are associated with Jews and Passover. Carcoifi alla giudia – literally Jewish style artichokes “is among the best known dishes of Roman Jewish cuisine.” Artichokes are a spring thistle and traditionally served at Passover in Italy. Whether or not from a culinary history this dish sprung from the use of raw artichoke for marror is not known, but we can say with certainty that artichokes have a considerable history when it comes to Passover.

Horseradish only became popular, in all likelihood, because an early Pesach, would be too soon for any greens and thus they were left with horseradish – which is not bitter at all, instead it is spicy or more particularly hot. In Galicia in the 19th century the use of horseradish was so ingrained that permission was even granted and affirmed for people to use less than a

kezayit and still recite the blessing. In light of this, the custom yields the possibility that all sort of other spicy items be used for

marror including very hot jalapeño peppers, for example.[31] Since we are discussing herbs, it is also worth noting that recently rulings regarding the use of marijuana and Pesach have been issued both in Israel and the United States (

here), for our discussion on marijuana and Pesach please see

here.

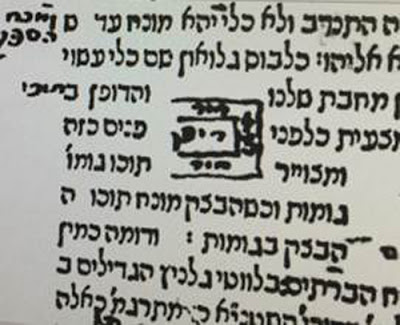

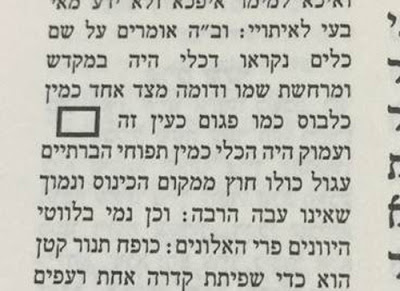

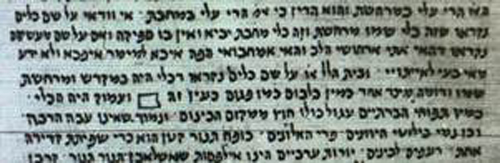

One manuscript captures the uncertain identification of

marror. In the Tubingen Haggadah, the place where the illustration for

marror is left blank, presumably to permit the owner to fill in what they are accustomed to use.

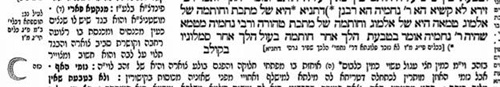

Marror is not the only vegetable that is eaten during the seder, another difficult to identify is the

karpas. Today there are a variety of items used, and in reality, any dip-able vegetable will suffice, historically, it seems that lettuce or celery was used. The Birds Head provides that “

lattich (lettuce) and

eppich (celery) should be used. These are traditional salad foods, which, in the normal course of things, would be dipped or tossed with a dressing. A dressing can be a simple as vinegar, and indeed, in many medieval haggadot,

hometz or vinegar is used to dip. We can trace the change from the more obviously salad oriented vinegar to saltwater where in the Darmstadt Haggadah, a later hand wrote on top of

hometz –

mei melekh. While it appears nearly universal that

hometz was used, its disfavor may be connected to a rule unrelated to Passover. Since the Middle Ages, there is a dispute whether or not vinegar falls under the ambit of

stam yenam. Thus, the change to saltwater may be more of a reflection about views on what constitutes

stam yenam and less to do with tears.

One final food item is the

haroset preparation. Apples are familiar and linked to the midrash regarding birthing under an apple tree, in the Rothschild Machzor and the 2nd Nuremburg haggadah, cinnamon is called for because “it resembles straw.” It also concludes that “some incorporate clay into the

haroset to remind them of the mortar. For those wanting to replicate this addition, edible clay, kaolin, is now easily

procured, and there is even a preparation that creates

stone-like potatoes, perfect for the seder.

To be continued… but until then see these posts

Halakha & Haggadah, and regarding some illustrations in the iconic Prague 1526 Haggadah,

here and also Elliot Horowitz’s

discussion.