Who can discern his errors?

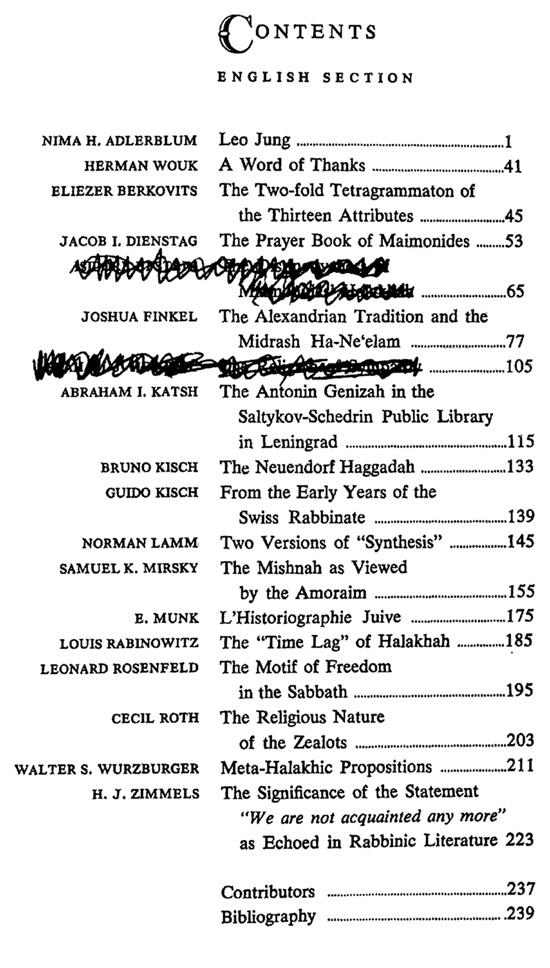

Misdates, Errors, Deceptions, and other Variations in and about Hebrew Books, Intentional and

Otherwise: Revisited[1]

by Marvin J. Heller

Marvin J. Heller is the award winning author of books and articles on early Hebrew printing and bibliography. Among

his books are the Printing the Talmud series, The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book(s): An Abridged Thesaurus, and collections of articles.

R. Eleazar once entered a privy, and a Persian [Roman] came and thrust him away. R. Eleazar got up and went out, and a serpent came and tore out the other’s gut. R. Eleazar applied to him the verse, “Therefore will I give a man (אָדָם adam) for thee (Isaiah 43:4).” Read not adam [a man] but אֱדֹם edom [an Edomite = a Roman] corrected by the censor to “but a Persian.” (Berakhot 62b)

“R. Eleazar said: Any man who has no wife is no proper man; for it is said, Male and female created He them and called their

name Adam” corrected by the censor to “any Jew who is unmarried” (Yevamot 63a).[2]

Sensitivity to the contents of Jewish texts by non-Jews, and apostates in their employ, was a feature of Jewish life at various periods, one particularly notable and noxious time being in the sixteenth century when, during the counter-Reformation, the Church undertook to censor and correct those Hebrew books that were not placed on the index and banned in their entirety. In the first example, the understanding based on the reading of adam אָדָם as edom אֱדֹם (Rome) is completely lost by the substitution of Persian for Edom. In the second example “Any man who has no wife is no proper man” was deeply offensive to a Church that required an unmarried and celibate clergy. In both instances the text was altered to adhere to the Church’s sensibilities despite the fact that not only was the original intent lost but that, particularly in the first case, it ceased to be meaningful.

Books, and even more so Hebrew books, often underwent modifications, textual changes, due to the vicissitudes and complexities of the Jewish condition, frequently involuntary. The subject of “Misdates, Errors, Deceptions, and other Variations in and about Hebrew Books, Intentional and Otherwise,” addresses textual changes, as well as other errors, intentional and unintentional, that may be found in Hebrew books. Addressed previously in Hakirah, this is a companion article, providing additional examples of book errors, variations, and discrepancies. As noted previously, errors “come in many shapes and forms. Some are significant, others are of little consequence; most are unintentional, others are purposeful. When found, errors may be corrected, left unchanged, or found in both corrected and uncorrected forms. . . . Other errors are not to be found in the book per se but rather in our understanding of the book. This article is concerned with errors in and about Hebrew books only. It is not intended to be and certainly is not comprehensive, but rather explores the variety of errors, some of consequence, most less so, providing several interesting examples for the reader’s edification and perhaps enjoyment.”[3]

Among the errors discussed in this article are 1) those dealing with the expurgation of the Talmud; 2) expurgation of other Hebrew works; 3) internal censorship, that is, of Hebrew books by Jews; 4) accusations of plagiarism and forgery; 5) misidentification of the place of printing; 6) confusion due to mispronunciations.

I

Returning to the beginning of the article, the Talmud, initially banned in 1553 and placed on the Index librorum prohibitorum in 1559, was subsequently permitted by the Council of Trent in 1564, but only under restrictive and onerous conditions. Reprinted in greatly censored form, the introductory quote refers to modifications in the Basle Talmud (1578-81). A condition of the Basle Talmud was that the name “Talmud” be prohibited. Heinrich Graetz explains the Pope’s and Council’s considerations in forbidding the name.

the Council only approved the list of forbidden books previously made out in the

papal office, the opinion of the pope and those who surrounded him served as

a guide in the treatment of Jewish writings. The decision of this point was left to the pope, who afterwards issued

a bull to the effect that the Talmud was indeed accursed – like Reuchlin’s ‘Augenspiegel

and Kabbalistic writings’ – but that it would be allowed to appear if the name

Talmud were omitted, and if before its publication the passages inimical to

Christianity were excised, that is to say, if it were submitted to censorship

(March 24th, 1564). Strange, indeed, that the pope should have allowed the

thing, and forbidden its name! He was afraid of public opinion, which would

have considered the contradiction too great between one pope, who had sought

out and burnt the Talmud, and the next, who was allowing it to go untouched. At

all events there was now a prospect that this written memorial, so

indispensable to all Jews, would once more be permitted to see the light,

although in a maimed condition.[4]

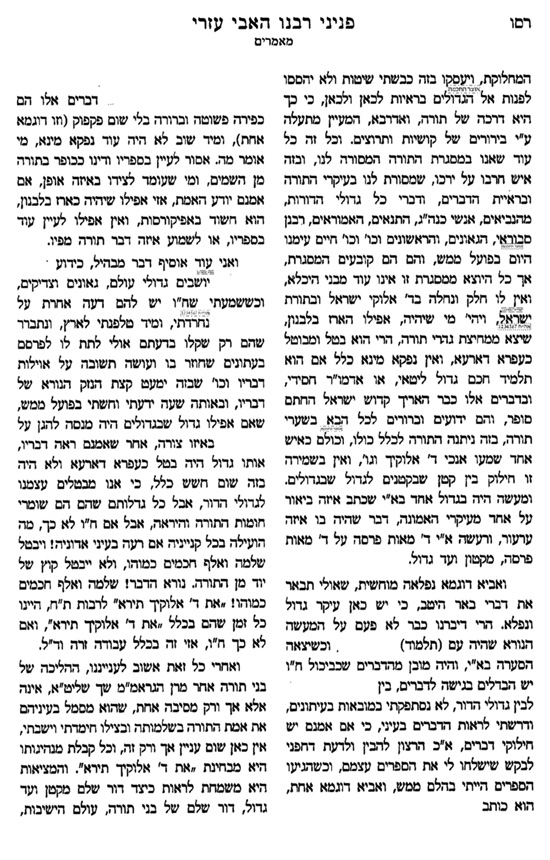

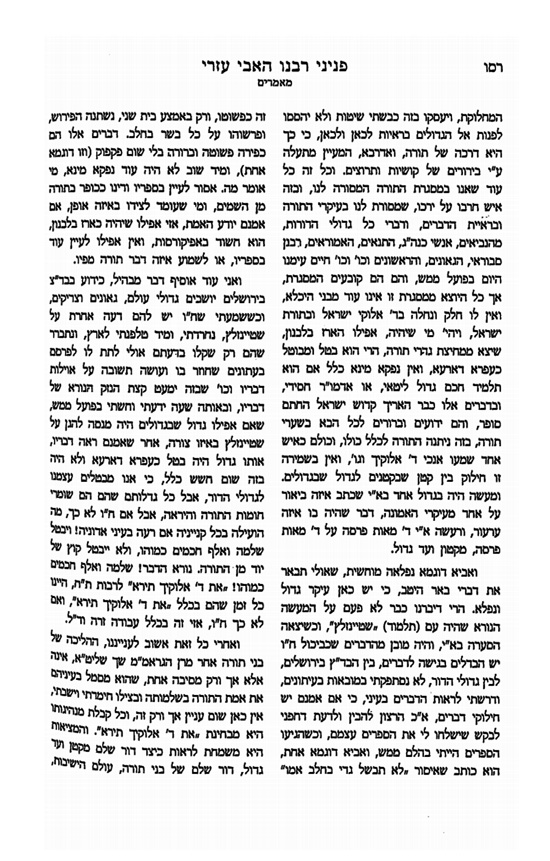

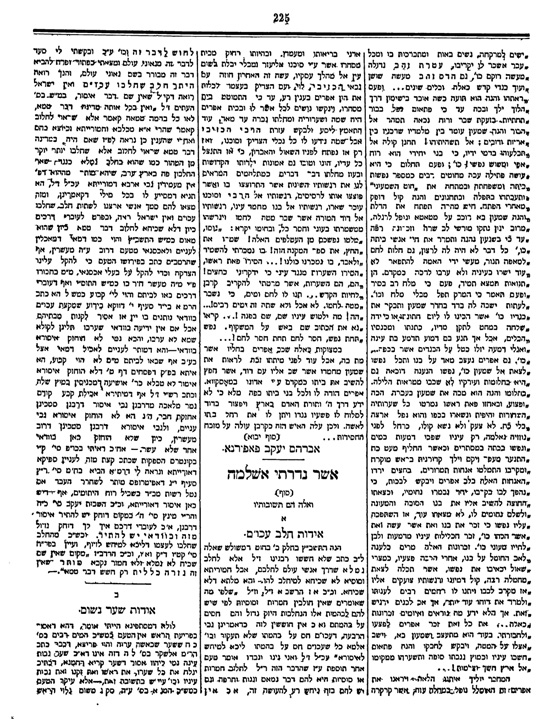

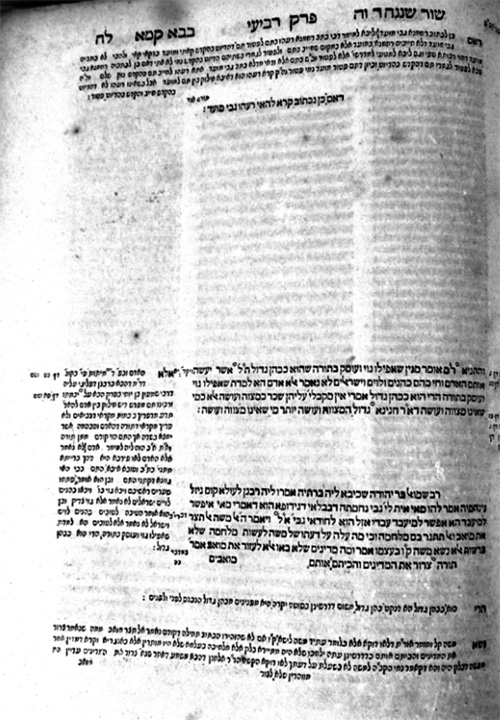

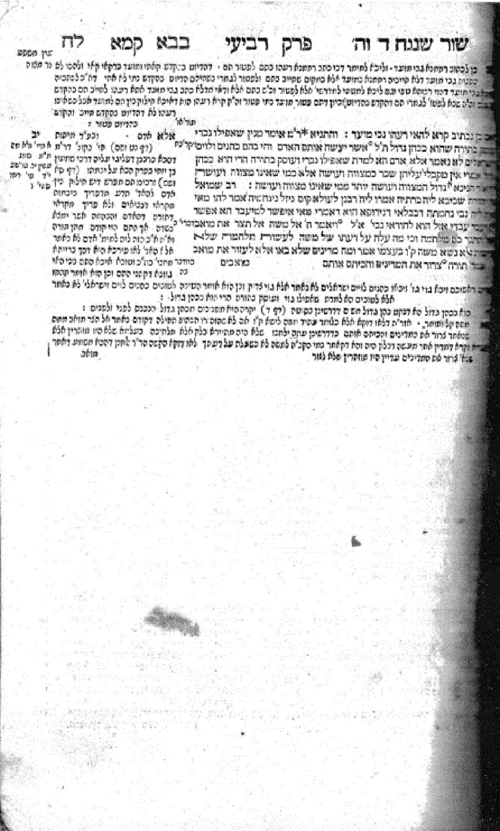

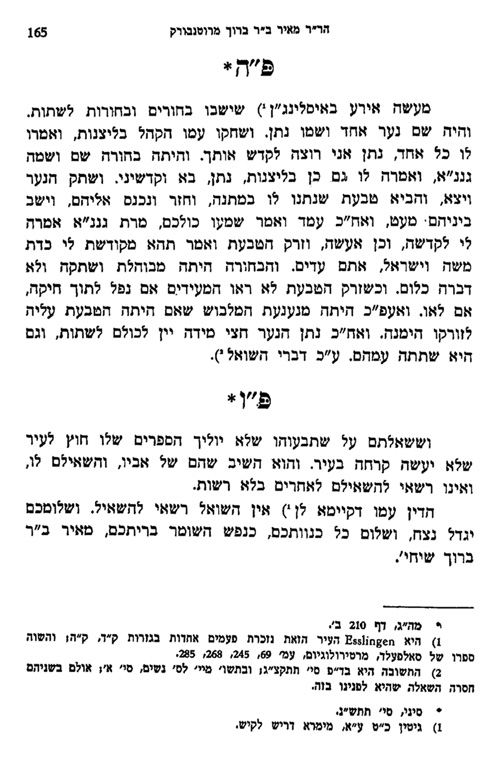

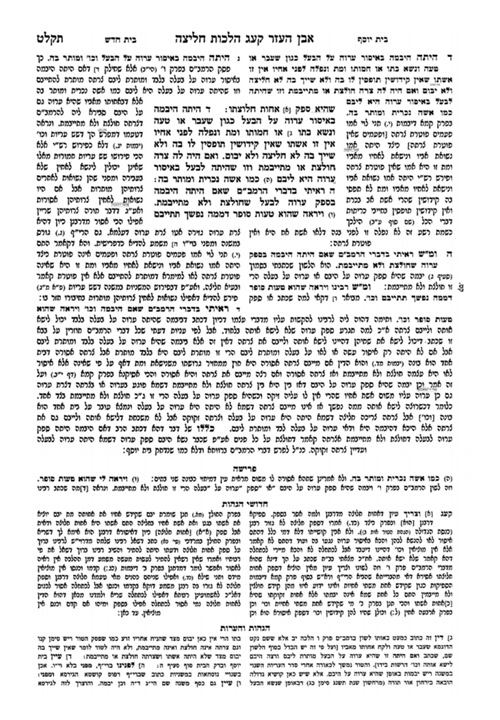

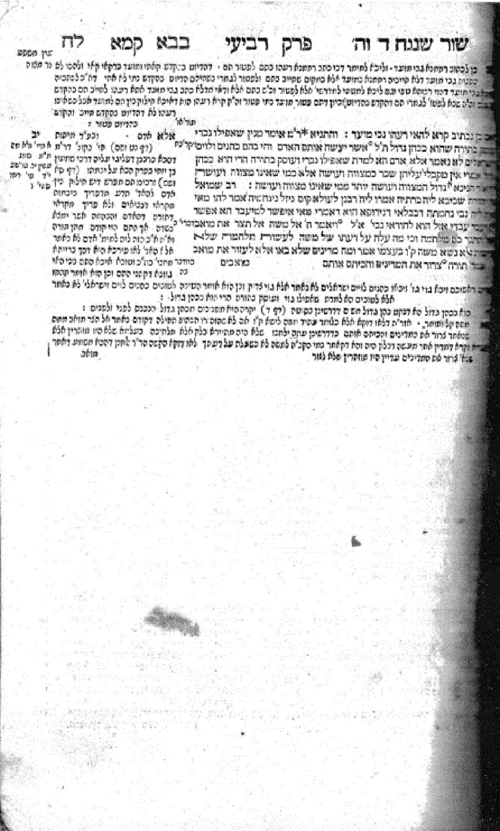

Among the most egregious examples of censorship of the Talmud is Bava Kamma 38a. That amud (page) of the Talmud, dealing with financial relations between Jews and non-Jews, was expurgated, almost in its entirety. Prior to the much censored Basle Talmud (1578-1581) the text was completely printed, for example, in the 1519/20-23 Venice edition of the Talmud published by Daniel Bomberg. After the censored Basle Talmud was published, initially, rather than contract the text, large blank spaces were left, clearly indicating that text had been expurgated.

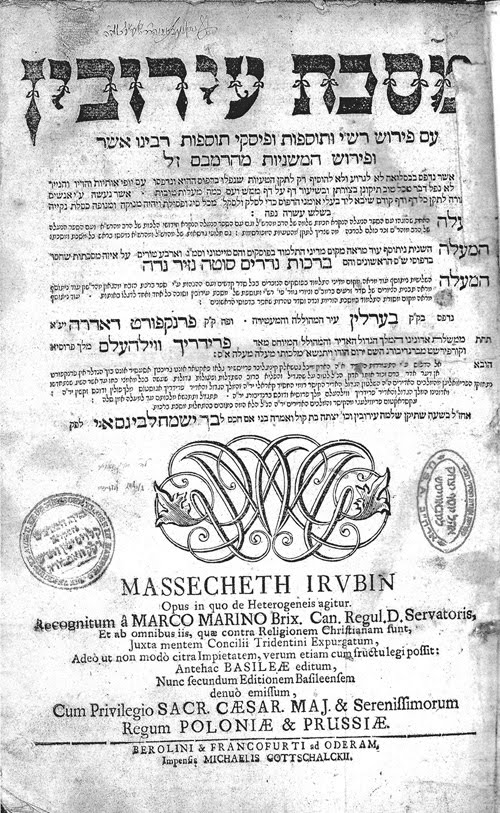

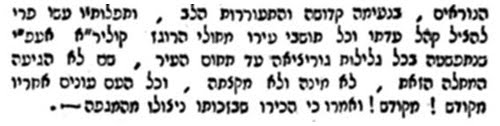

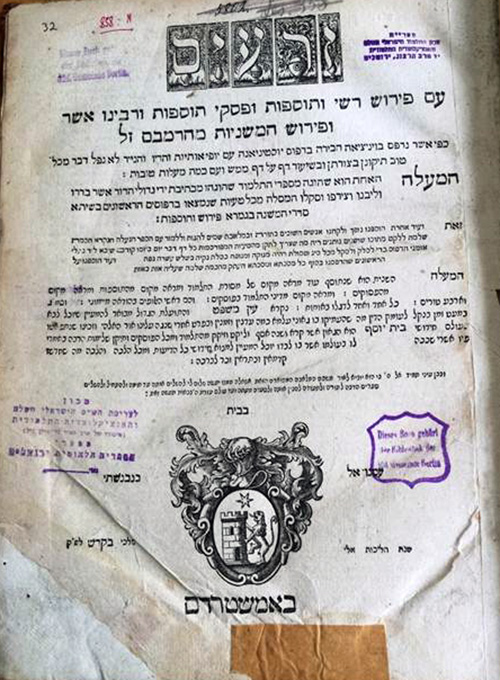

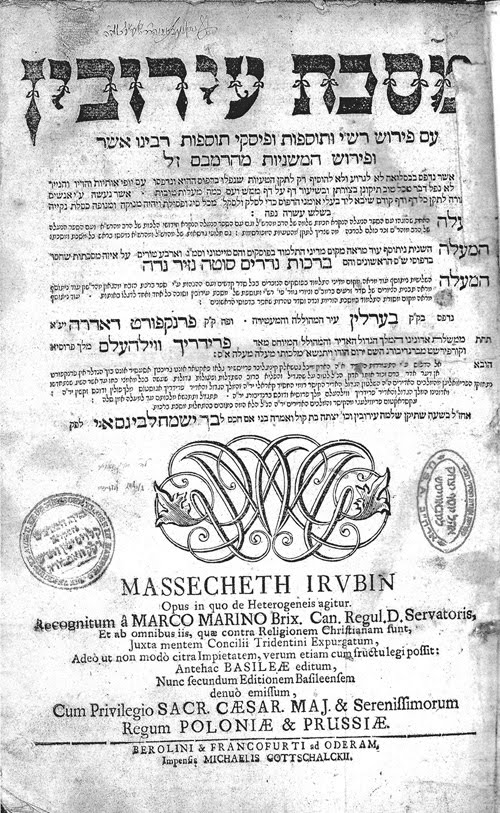

Abraham Karp notes that in some editions of the Talmud “many expurgated passages are restored, and where deletions are retained, blank spaces are left to indicate the omission to the reader and, no doubt, to permit him to fill in by pen what they dared not to print.”[5] An example of the blank spaces can be seen from the Frankfurt an der Oder Talmud 1697-99, printed by Michael Gottschalk. Such omissions are to be found in almost all seventeenth and early eighteenth editions of the Talmud, a notable exception being the Benveniste edition (Amsterdam, 1644-47).[[6] Rabbinovitch too notes that blank spaces were left for expurgated text, those omissions being consistent with the Basle Talmud. He adds, however, that this policy was followed until the 1835 Vilna Talmud. At that time government officials prohibited the practice so that the omissions would not be so obvious.[7] In fact, text was consolidated much earlier, as evidenced, by the illustrations of Bava Kama 38a from the 1734‑39 Frankfurt an der Oder Talmud. This expurgated material is restored in current editions of the Talmud.

Frankfurt an der Oder – 1697-99

Frankfurt an der Oder – 1734-39

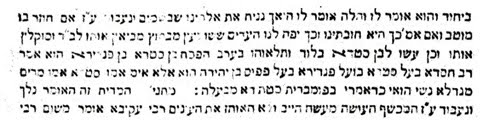

Another example of interest, one that has not fared as well, the text not yet restored in most editions of the Talmud, is to be found in

Shabbat 104b and

Sanhedrin 67a. The reference there is to Ben Satda, beginning, in the latter tractate “and so they did to Ben Satda

in Lod, and hung him on

erev Pesah. Ben Satda? He was the son (ben) of Padera . . .”[8] Popper notes that Gershom Soncino, when publishing “a few of the Talmudic tracts at Soncino during the last decade of the fifteenth century, he took care not to restore any of the objectionable words in the MSS. from which he printed.”[9] Here too the text is complete in the Bomberg Talmud. Two subsequent exceptions in later editions of

Sanhedrin where the Ben Satda entries do appear are in the Talmud printed by Immanuel Benveniste and in the edition of

Sanhedrin printed in Sulzbach in or about 1696.

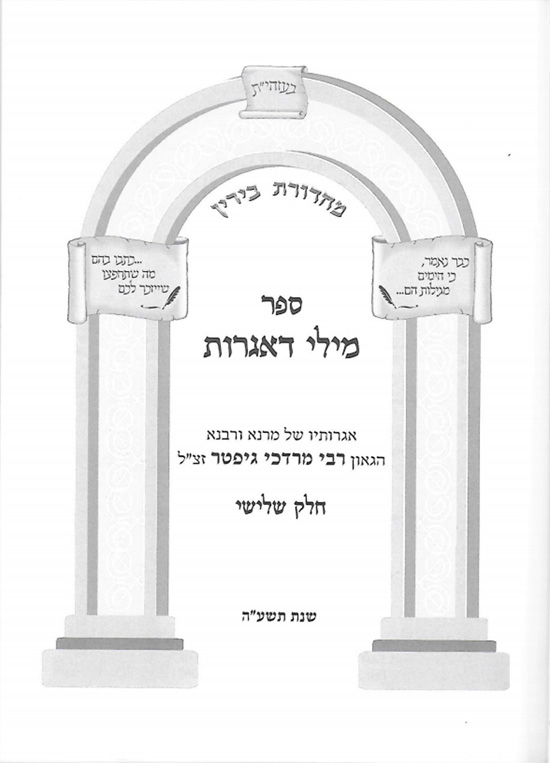

Sanhedrin 67a, Benveniste Talmud

However, in two complete editions of the Talmud (1755-63, 1766-70) printed in Sulzbach, the Ben Satda entries are omitted, as is the case of most modern editions of the Talmud.[10]

II

The Talmud isn’t the only work to have been censored. Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin provides several examples of text in books

that were modified due to the censor’s ministrations. Among them is R. Abraham ben Jacob Saba’s (d. c. 1508) Zeror ha-Mor, a commentary on the Pentateuch based on kabbalistic and midrashic sources.[11] On the passage “They would slaughter to demons without power, gods whom they knew not, newcomers recently arrived, whom your ancestors did not dread” (Deuteronomy 32:17), referring to “Christians in general and priests in particular as ‘demons’ (shadim): ‘For as the nations of the world, all their abominations and vanities come from the power of demons, hence, the monks would shave the hair of their heads and leave some at the top of the head as a stain.’” This passage continues, referring to bishops and popes, concluding that their entire heads are shaved like a marble with only a bit of hair about their ears, so that they have the appearance of demons, hairless, and like demons, provide no blessings, are like a fruitless tree, and “thus, it is fitting that they bear no sons of daughters.” Raz-Krakotzkin informs that this passage appeared in the first two editions of Zeror ha-Mor printed by Bomberg, and the Giustiniani edition (1545) but was already expurgated by the Cavalli edition (1566), a blank space in place of the text. That space subsequently disappeared and, although a Cracow edition based on the Bomberg Zeror ha-Mor restored the text it remains missing from most later editions.[12] Raz-Krakotzkin continues, citing additional examples.

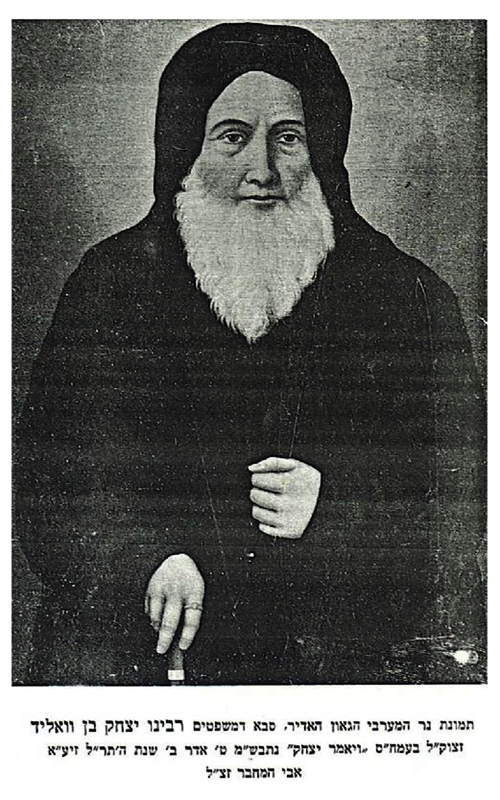

Early halakhic works were also subject to the ministrations of the censor.[13] Among them are such works as R. Samson ben Zadok’s (thirteenth century) Sefer Tashbez (Cremona, 1556). Samson was a student of R. Meir of Rothenburg (Maharam, c. 1220-1293). When the latter was imprisoned in the tower of Ensisheim, Samson visited him regularly, serving as his attendant and carefully recording in Tashbez Maharam’s teachings, customs, and daily rituals, as well as what he heard and observed, from the time Meir rose in the morning until he retired at night, on weekdays, Sabbaths, and festivals. Although a relatively small work (80: [6], 55 leaves), it consists of 590 entries beginning with Sabbath night (1-17), Sabbath day (18-98), followed by festivals, Sefer Torah, priestly benedictions, prayer, slumber, talis and tefillin, benedictions, issur ve-heter (dietary laws), redemption of the first born, hallah, vows, marriage and divorce, monetary laws, and piety. Expurgation by the censor of Tashbez was done sloppily, for terms such as meshumad and goy, normally excised, remain, but with a disclaimer near the end that they refer to idol worshipers only.[14]

III

Not all errors are due to the ministrations of the censor. Jews, too, at times, have taken their turns at modifying the text of books.

A recent and perhaps quite surprising example of internal censorship is to be found in R. Solomon Ganzfried’s (1804–1886) Kizzur Shulḥan Arukh. First printed in 1864, that work an abridgement of the Shulhan Arukh for the average person, went through fourteen editions in the author’s lifetime, and numerous editions since then, as well as translations into many languages and has been the subject of glosses.[15] Marc B. Shapiro informs that in the Lublin (1904) edition of the Kizzur Shulḥan Arukh and several other editions the entry (201:4) that “apostates, informers, and heretics –for all these the rules of an onan and of mourners should not be observed. Their brothers and other next of kin should dress in white, eat, drink, and rejoice that enemies of the Almighty have perished,” the words “apostates, informers, and heretics” have been removed. In the Vilna edition (1915) the entire paragraph is removed and the sections renumbered from seven to six. In the Mossad Harav Kook vocalized edition a new halakhah was substituted, but that has since been corrected to reflect the original text. The reason, according to Shapiro, is that with the expansion of Jewish education to include girls, it was felt that schoolchildren, with assimilated relatives, would see this as referring to family members.[16] Several recent editions of the Kizzur Shulḥan Arukh that were examined, in both Hebrew and English, have the original text.

R. Abraham Isaac Kook (1865–1935), chief rabbi of Jerusalem and first Ashkenazic chief rabbi in Israel (then Palestine),

was a profound, influential, and mystical thinker. Highly regarded by his contemporaries, his strongly Zionist views also resulted in some opposition, but even most of his contemporaries who disagreed with him held him in high regard. Shapiro notes that with time, Kook’s reputation changed. Despite the fact that such pre-eminent rabbis as R. Solomon Zalman Auerbach (1910-95) and R. Joseph Shalom Elyashiv (1910-2012) were unwavering in their high regard of Kook, strong anti-Kook sentiment developed later in religious anti-Zionist circles. Shapiro notes that “Kook has been the victim of more censorship and simple omission of fact for the sake of haredi ideology than any other figure. When books are reprinted by haredi and anti-Zionist publishers Kook’s approbations (hascomas) are routinely omitted.” One of several examples of this modified opinion Shapiro cites is a lengthy eulogy delivered by R. Isaac Kossowsky (1877-1951) praising Kook. When the eulogy was reprinted in She’elot Yitzhak, a collection of Kossowsky’s writings, the name of the subject of the eulogy, Rav Kook, was omitted. In the reprint of She’elot Yitzhak the eulogy is deleted in its entirety.[17]

Shapiro’s observation about Rav Kook’s approbations is confirmed in several books. R. Eliezer Mansour Settehon’s (Sutton, 1860-1937) Notzar Adam: Hosafah Notzar Adam (Tiberius, 1930), discourses on spiritual development, has approbations from R. Abraham Abukzer, R. Moses Kliers, and R. Jacob Hai Zerihan, and R. Abraham Isaac ha-Kohen Kook. In a description of Notzar Adam in in Aleppo, City of Scholars (Brooklyn, 2005), Kook’s name, Kook’s name is omitted from a list of the book’s approbations.[18]

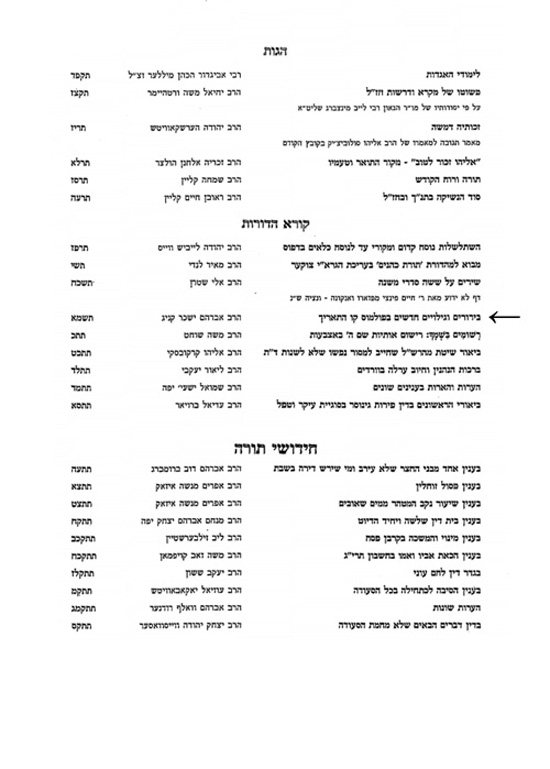

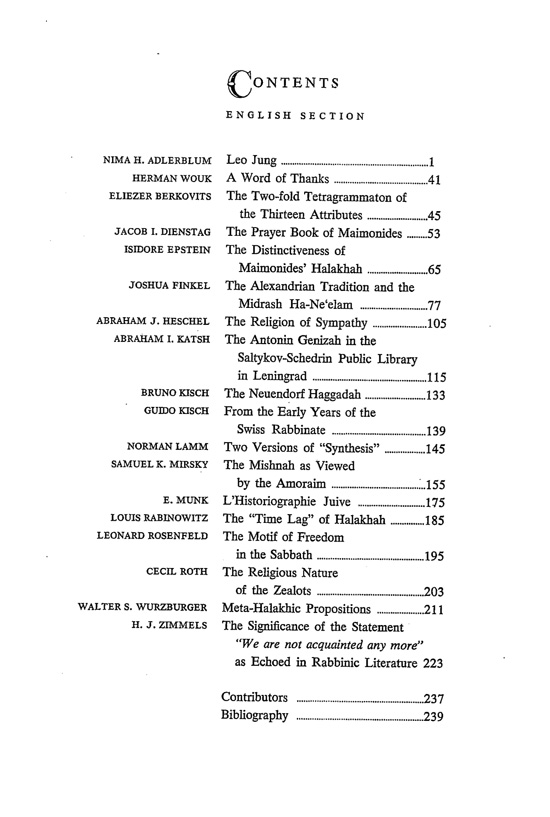

In a variation of this, two internet sites that reproduce the full text of Hebrew books both include Rav Isaac

Hutner’s (1906-80) Torat ha-Nazir (Kovno, 1932). This, the first edition, has three approbations; a full page hascoma from R. Hayyim Ozer Grodzinski (1863–1940), and the following page two approbations, side by side, from R. Abraham Duber Kahana (1870–1943) and Rav Kook. The first internet site, with more than 53,000 books for free download, follows R. Grodzinski’s approbation with a blank page and then the text. The second, a subscription site with more than 76,000 scanned books, goes directly from R. Grodzinski’s hascoma to the text, dispensing with the blank page, also not reproducing the second page of approbations. It is not clear whether the copies scanned were faulty, the scanning incomplete, or the omission intentional. Nevertheless, to conclude this section on a positive note, surprisingly, given the omission of Rav Kook’s approbation in both scans of Torat ha-Nazir, both sites list and provide an extensive number of Rav Kook’s works.

IV

Accusations of plagiarism accompany the publication of two works by and/or attributed to R. Nathan Nata ben Samson Spira (Shapira, d. 1577). Spira, born to a distinguished family that was, according to the Ba’al Shem Tov, one of the three pure families throughout the generations in Israel (the others being Margulies and Horowitz), served as rabbi in Grodno (Horodno) until 1572, when he accepted a position in Posnan. His grandson was R. Nathan Nata ben Solomon Spira (Megalleh Amukkot, c. 1585-1633). Among Nathan Nata Spira’s works is Imrei Shefer (20: [1], 260 ff.), a super-commentary on Rashi and R. Elijah Mizrahi (c. 1450–1526). The book was brought to press by Spira’s son R. Isaac Spira (d. 1623), Rosh Yeshiva in Kovno and afterwards in Cracow. Work on Imrei Shefer began in Cracow in 1591 but before printing was finished Isaac Spira accepted a position in Lublin where publication was completed at the press of Kalonymus ben Mordecai Jaffe (1597).[19]

The title-pages states that Spira, “gives goodly words (Imrei Shefer)’ (Genesis 49:21) and he gives, ‘seed to the sower, and bread לזורע ולחם (357=1597) to the eater’ (Isaiah 55:10) of Torah.” In the introduction, Isaac informs that the work is entitled Imrei Shefer from the verse, “he gives goodly words” (and the word “he gives הנתן” in the Torah is without a vav), implying the name of the author [Nathan נתן] and Shefer שפר is language of Spira שפירא the family name of the author. Isaac then addresses the existence of an unauthorized and fraudulent edition ascribed to his father, printed in Venice (Be’urim, 1593),

found and brought out by men who lack the yoke of the kingdom of heaven. A work discovered, who knows the identity of the author, perhaps a boy wrote it and wanted to credit it to an authoritative source אילן גדול), [my father my lord]. God forbid that his holy mouth should bring forth words that have no substance, vain, worthless, and empty, a forgery, “[And, behold], it was all grown over with thorns, and nettles had covered it over” (Proverbs 24:31).

Isaac Spira took his complaint to the Va’ad Arba’ah Artzot (Council of the Four Lands), requesting they prohibit the distribution of the Be’urim in Poland. The response of the Va’ad is printed at the end of the introduction,

It has been declared, by consent of the rabbis, and the [communal] leaders of these lands,

that these books shall neither be sold nor introduced into [any Jewish] home in

any of these lands. Those who have [already] purchased them shall receive their

money back and not keep [such] an evil thing in their home.

What was and who wrote the Be’urim, the reputedly plagiarized copy of R. Nathan Nata ben Samson Spira’s Imrei Shefer? The title-page of the Be’urim (40: 180 ff.), printed in Venice in 1593 “for Bragadin Giustiniani by the partners Matteo Zanetti and Komin Parezino at the press of Matteo Zanetti,” states that it was written by ha-Rav, the renowned, the gaon, R. Nathan from Grodno in the year, “For you shall go out with joy בשמחה (353=1593), and be led forth with peace” (Isaiah 55:12). Be’urim does not have an introduction nor a colophon that provides any additional information.

Isaac Spira’s accusation that the Be’urim is a forgery, not to be ascribed to his father, but rather was written by an unknown young man who then attributed it to Spira, is confirmed by R. Issachar Baer Eylenburg (1550-1623), who writes in his responsa, Be’er Sheva (Venice, 1614) and also in his commentary on Rashi, Zeidah La-Derekh (Prague, 1623) that it is obvious that the Be’urim were not the work of the holy Spira, but rather of an erring student “who hung (attributed it) to himself, hanging it on a large tree” (cf. Pesahim 112a).[20]

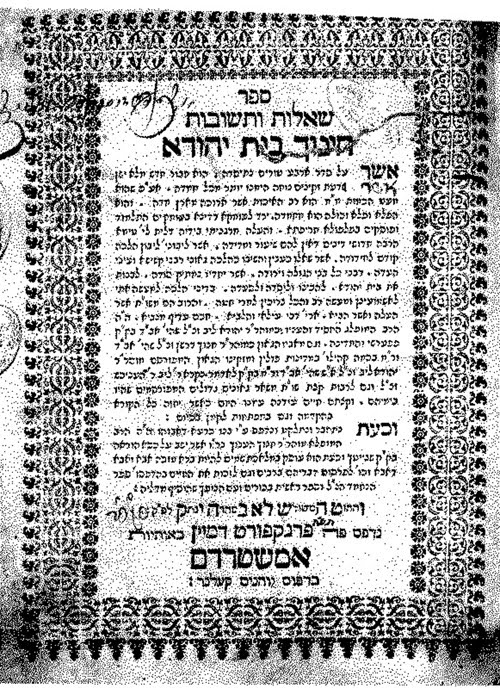

Among the distinguished sages of medieval Sepharad is Rabbenu Bahya ben Asher ben Hlava (c. 1255-1340). Best known for his popular, multi-faceted, and much reprinted Torah commentary, written in 1291 and first published in Naples (1491), Rabbenu Bahya was also the author of Kad ha-Kemaḥ (Constantinople, 1515) and Shulḥan shel Arba (Mantua, 1514). The former, Kad ha-Kemaḥ, is comprised of sixty discourses on varied subjects, among them festivals, prayer, faith, and charity, all infused with ethical content. Among the numerous editions of Kad ha-Kemaḥ is a scholarly edition entitled Kitvei Rabbenu Baḥya (Jerusalem, 1970) edited and with annotations by R. Hayyim Dov Chavel (1906–1982).

Among the essays in Kad ha-Kemaḥ is one entitled Kippurim, on Yom Kippur. Part of that discourse includes a commentary on the book of Jonah, read on Yom Kippur. Chavel, in the introduction to his annotations on Rabbenu Bahya’s commentary on Jonah, suggests that Rabbenu Bahya took his commentary from R. Abraham ben Ḥayya’s (d. c. 1136) Hegyon ha-Nefesh, first published by E. Freimann (Leipzig,

1860). Abraham ben Ḥayya, a resident of Barcelona, was a philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer, reflected in his several works, including translations from the Arabic. Hegyon ha-Nefesh “deals with creation, repentance, good and evil, and the saintly life. The emphasis is ethical, the approach is generally homiletical – based on the exposition of biblical passages – and it may have been designed for reading during the Ten Days of Penitence.”[21] Kitvei Rabbenu Baḥya and Hegyon ha-Nefesh are sufficiently alike to support Chavel’s contention that

Rabbenu utilized the Sefer Hegyon ha-Nefesh (or Sefer ha-Mussar) of the earlier sage R. Abraham ben Ḥayya ha-Nasi, known as ṣāḥib-al-shurṭa . . . In it is found this commentary on the book of Jonah. This was already noted by the author of Zaphat ha-Shemen – the usage by Rabbenu of this book is comparable to his use of other works: according to his needs. The reason that he does not mention it in his commentary is, perhaps, because the books of R. Abraham ha-Nasi were well known, and the leading sages, such as the Rambam, Ramban and other leading rabbis utilized it, comparable to “Joshua was sitting and delivering his discourse without mentioning names, and all knew that it was the Torah of Moses” (Yevamot 96b).[22].

We leave accusations of plagiarism and turn to forgery, a well-known case involving a person of repute, Saul Hirsch (Hirschel)

Berlin’s (1740-94)

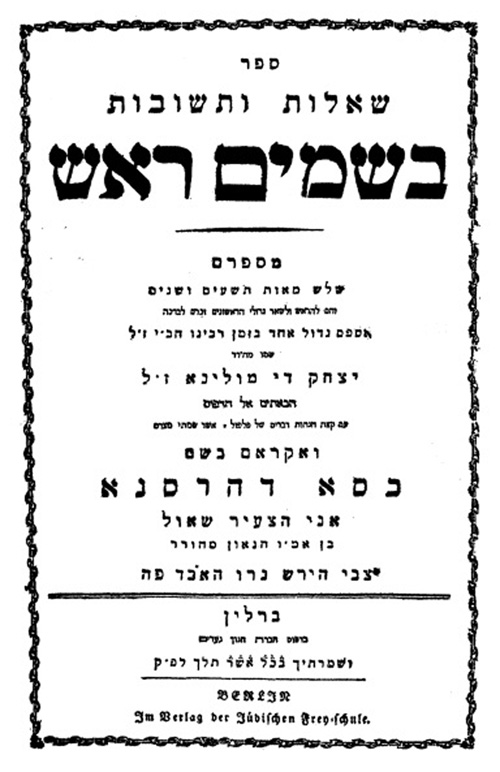

Besamim Rosh.[23]

Berlin was a person of great promise; the son of R.

Hirschel Levin (Ẓevi Hirsch, 1721–1800), chief rabbi of Berlin, ordained at the age of twenty and in 1768

av bet din in Frankfurt an der Oder. At some point Berlin became disillusioned with what he believed to be antiquated rabbinical authority. He gave up his official rabbinic position in Frankfurt, removing to Berlin. There Berlin was an associate of Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786), providing, in 1778, an approbation for Mendelssohn’s

Be’ur (Berlin, 1783) and was a supporter of the enlightenment figure

Naphtali Herz Wessely (1725–1805), writing an anonymous pamphlet in defense of Wessely’s

Divrei Shalom ve-Emet (Berlin, 1782) entitled

Ketav Yosher (1794).[24]

An earlier forgery of Berlin, described by Dan Rabinowitz, this under the pseudonym of Ovadiah bar Barukh Ish Polanya, was Berlin’s

Mitzpeh Yokteil (1789), a vicious attack on R. Raphael Kohen, rabbi of the three communities, Altona-Hamburg-Wansbeck, who had opposed Mendelssohn’s

Be’ur, and on Kohen’s

Torat Yekuteil (Amsterdam, 1772) on

Yoreh Deah. The Communities’

beit din placed Ovadiah, the presumed author, under a ban. The ban’s proponents approached R. Tzevi Hirsch, the chief rabbi of Berlin and Saul Berlin’s father, seeking his signature on the ban.[25] It appears that Tzvi Hirsch initially concurred with the ban, but, as he was close to deciding in favor of signing the ban, someone whispered in his ear the verse “woe is me, my master, it is borrowed שאול” (II Kings 6:5), – which he understood to be a play on שאול (borrowed), referring to his son, Saul, the true author of

Mitzpeh Yokteil.[26]

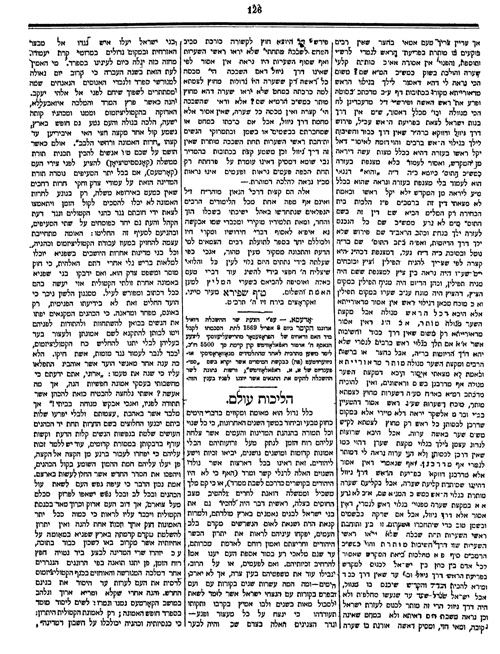

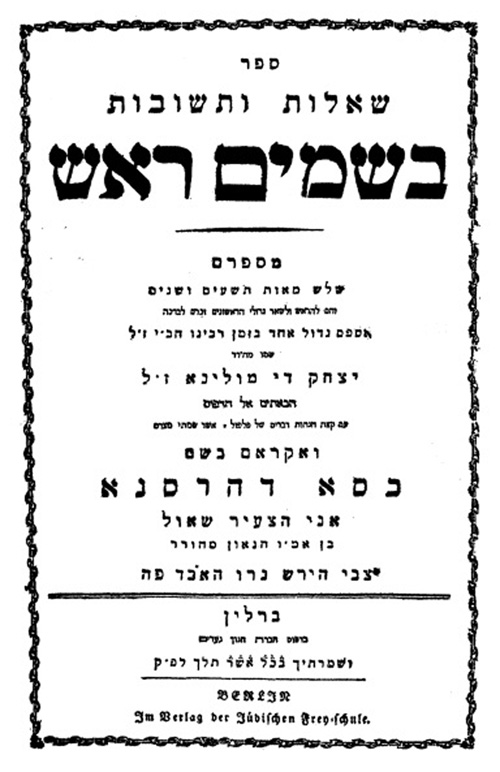

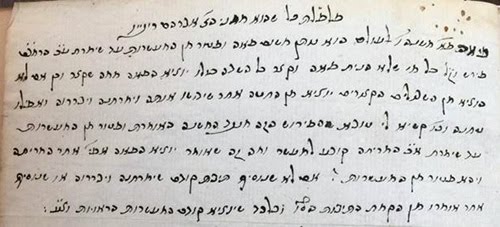

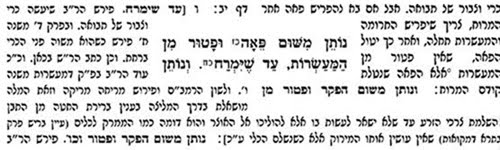

Turning to Besamim Rosh Saul Berlin’s infamous forgery, it claims to be the responsa of R. Asher ben Jehiel (Rosh, c. 1250–1327), among the most preeminent of medieval sages of European Jewry. The title-page describes it as the responsa Besamim Rosh, 392 responsa from books from the Rosh and other rishonim (early rabbinic sages) compiled by R. Isaac di Molina and with annotations Kasa de-Harshana by the young Saul ben R. Ẓevi Hirsch, av bet din, here (Berlin).[27] It is dated “and will keep you in all places where you goושמרתיך בכל אשר תלך 553 = 1793)” (Genesis 28:15), note Asher אשר in the date. In Besamim Rosh Berlin, having become an adherent of the haskalah, presents ideas inconsistent with and at variance with traditional halakhic positions. Among the novel responsa are removing the prohibition on suicide due to the difficult conditions of Jewish life; permitting shaving on Hol ha-Mo’ed; requiring a shohet to test the sharpness of his knife on his tongue; saying a blessing over non-kosher food; disregarding commandments that are upsetting; not taking Megillat Esther seriously; and that Jews beliefs can change. An example of the responsa, albeit a brief one and without Berlin’s Kasa de-Harshana, is the much quoted responsum concerning “legumes, rice, and millet which some Ashkenazic rabbis prohibit and is the practice in some communities. . .” (105b: no. 138): The responsum states:

This is very strange, for the Talmud permits it and no bet din is known to have made such an enactment. It is not for us to inquire why such an enactment was made and why it was followed by some. Possibly because of the exiles and the confused גירושים והבלבוחים, weighed down in poverty . . . and also due to the small community of Karaites in their midst who were also exiled. . . . unable to distinguish between bread and bread and all leavening from which it is possible to make flour and bread. But, God forbid, that we freely prohibit that which is permitted, and all the more because of the poor and needy, who lack sufficient meat and bread all the days of the festival. . . . “who eat [but] a litra of vegetables for at a meal” (Sanhedrin 94b). Also “a leap year is not intercalated in the year following a Sabbatical year for this reason.” All the more (kal ve-homer) to prohibit most types of food to the poor and needy on festivals and the overly strict (mahmerin) will have to answer on the day of judgement.

How has Besamim Rosh been received? Soon after its publication R. Wolf Landsberg, in Ze’ev Yitrof (Frankfurt an der Oder, 1793), stated that Besamim Rosh was a forgery, and R. Mordecai Benet (1753-1829) wrote to Berlin’s father, that Besamim Rosh was “from head to foot only wounds and grievous abscesses from sinful, vile men.”[28] R. Hayyim Joseph David Azulai (Hida, 1724–1806) in his Shem ha-Gedolim, one of several works in which he mentions Besamim Rosh, states “I have heard ‘a voice of a great rushing’ (Ezekiel 3:12) that there are in this book strange things. . . . Therefore the reader should not rely on it.”[29] The Hatam Sofer (R. Moses Sofer, 1762–1839), based on the responsum on suicide, also concluded that Besamim Rosh was a forgery.[30] Among the varied modern authorities who quote Besamim Rosh, albeit critically, are R. Solomon Joseph Zevin (1885–1978) and R. Ovadia Yosef (1920-13) the latter writing an approbation for the 1984 edition of Besamim Rosh.[31]

How influential was Besamim Rosh? Fishman writes that “Besamim Rosh is of itself cast as a work of rabbinic literature, a Trojan horse of sorts, capable of injecting reformist viewpoints directly into the camp of halakhic discourse. Indeed, the sheer frequency with which Besamim Rosh has been cited in subsequent halakhic writings [documented by Samet] raises the question of whether the work may not have been effective in introducing unconventional perspectives into rabbinic thought.”[32] Similarly, Shmuel Feiner notes that “Some scholars

regard Besamim Rosh as the beginning of the reform of Judaism.”[33] Finally, knowledge that Besamim Rosh was a forgery was so widespread, that it is even so described in a book dealers catalogue, that of Jakob Ginzburg, in Listing of Rare and Valuable Books (Minsk, 1914), stating “565 Besamin Rosh attributed to the Rosh, poor condition Berlin, 1792, 50 1.”

V

Of less consequence is a common error, if it may be so described, that is, the misleading identification of the place of printing on the title-pages of late seventeenth through the early nineteenth century books. Amsterdam, from the early seventeenth century, was the foremost center of Hebrew printing in Europe. Its reputation was such that printers in other lands, often with the only the most tenuous, if any, connections with Amsterdam, attempted to associate their imprints with that city. In a wide variety of locations the actual place of printing is minimized; what is enlarged is that the letters are באותיות אמשטרדם Amsterdam letters. Mozes Heiman Gans describes this practice,

Amsterdam may have had an embarrassing lack of rabbinical training facilities, but thanks to the Hebrew printing works it nevertheless had a great name in the world of Jewish scholarship. Moreover, the haskamot (certificate of fitness) was also sought by Jewish printers abroad, and so highly-prized were books ‘printed in Amsterdam’ or ‘be-Amsterdam’ that cunning rivals invented the phrase ‘printed ke-Amsterdam’, i.e. in the manner of Amsterdam, hoping to deceive the readers by relying on the similarity of the Hebrew k and b.[34]

An early example of this practice is in Dessau, where the court Jew, Moses Benjamin Wulff, established a Hebrew press in Anhalt-Dessau.[35] Approval for the press was given on December 14, 1695 by Princess Henriette Catherine of Orange, Prince Leopold I’s mother, acting as regent in her son’s frequent absences in the service of the Prussian army. The first books were published in 1696, among them R. Jacob ben Joseph Reischer’s (Jacob Backofen, c. 1670–1733) Hok Ya’akov and Solet le-Minhah ve-Shemen le-Minhah, and the following year R. Shabbetai ben Meir ha-Kohen’s (Shakh, 1621–1662) Gevurat Anashim, each with a title-page, with a pillared frame topped by an obelisk and the statement,

Printed here [in the holy congregation of] Dessau with AMSTERDAM letters

Under the rule of her ladyship, the praiseworthy and pious Duchess, of distinguished birth HENRIETTE CATHERINE [May her majesty be exalted]

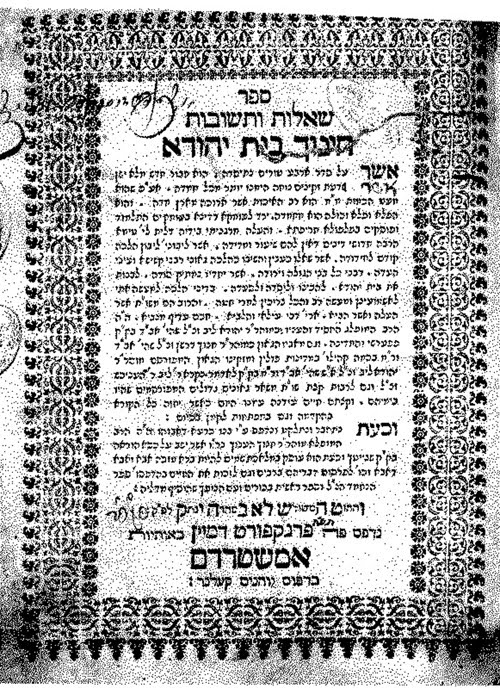

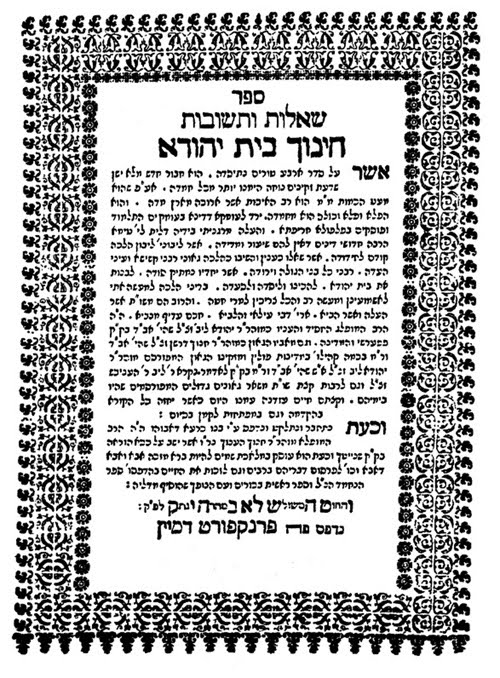

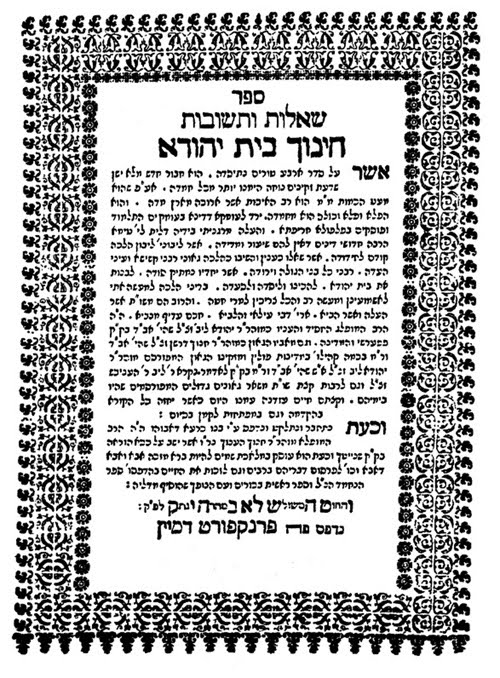

Another notable instance are the title-pages of R. Judah Leib ben Enoch Zundel’s (1645–1705) Hinnukh Beit Yehudah (Frankfurt am Main, 1708), a collection of one hundred forty-five responsa, among them several by the author. Zundel (1645–1705), who succeeded his father as rabbi of the district of Swabia in 1675, subsequently relocated to Pfersee, where he remained until his death. Judah Leib was also the author of Reshit Bikkurim (Frankfurt, 1708), homilies by Judah Leib and his father. The sermons in that work are on festivals and Sabbaths based upon R. Joseph Albo and includes excerpts from a commentary on the Bible which Judah Leib had intended publishing.[36]

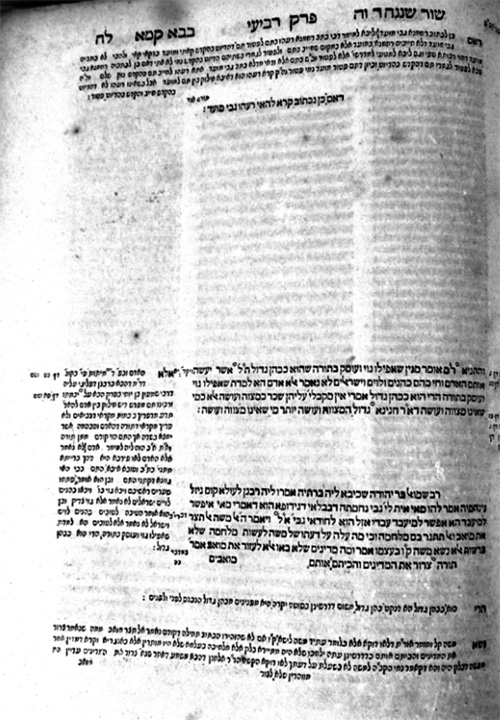

The publisher of these books was Johann Koelner, the distinguished Frankfurt am Main printer (1708-27), credited with publishing half of the Hebrew books printed in Frankfurt up to the middle of the nineteenth century as well as a fine edition of the Babylonian Talmud.[37] Koelner began printing with Hinnukh Beit Yehudah; it is unusual in that there are two title-pages for the book, one noting that it was printed in Frankfurt am Main, the other stating that Hinnukh Beit Yehudah was printed, in an enlarged font with, Amsterdam, in a smaller font, letters, and the place of printing, Frankfurt am Main, also set in a smaller font.[38]

Another way of emphasizing Amsterdam fonts rather than the city in which a book was printed is evident from R. Jacob Uri Shraga Feival’s ben Menahem Nachum’s Bet Ya’akov Esh (Frankfurt an der Oder, 1765) on Job. Here, somewhat unusually, even the reference to the source of the fonts is highlighted, saying with Amsterdam letters. The place of printing is given below in abbreviation in a slightly smaller font as printed here פ”פ דאדר (Frankfurt an der Oder).

In addition to several locations in Germany, such as Hamburg and Jessnitz, we also find this practice in such varied locations as in Zolkiew, for example, R. Aaron Moses ben Zevi Hirsch of Lvov (Lemberg) Ohel Moshe (1765) on grammar; in Lvov, on the title-page of R. Jacob ben Baruch of Tyczyn’s (c. 1640-1725) Birkat Yosef (1784) on Shulhan Arukh Hoshen Mishpat; and with a mahzor that states, in large red letters, that it was printed in Slavuta and, in a small font in German only, that is, it was printed (gedrukt) in Lemberg. We also find this done, somewhat far afield, in Livorno; the title-page of Seder Nezikin of the Jerusalem Talmud (1770), printed with a frame that is like but not exact of the Amsterdam edition of Seder Nashim (1754), by Carlo Giorgi, stating “printed here, Livorno, with Amsterdam letters.

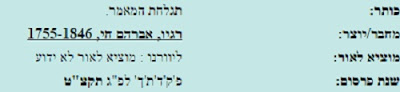

And then there are inadvertent errors, such as misreading a colophon. Popular books, frequently reprinted, go through numerous editions. At times it is difficult to identify early editions and, as might be expected, books are occasionally misidentified, attributed to the wrong press, misdated, and there are instances when editions are recorded that never existed. All of these errors can be found in R. Leon Modena’s (Judah Aryeh, 1571-1648) Sur me-Ra.[39]

Sur me-Ra, a popular and much reprinted tract opposing the snares and consequences of gambling, was written by Modena when, according to his autobiography, he was only twelve or thirteen years old. Paradoxically, Modena would later become a compulsive gambler, even gambling away his daughters’ dowries. Translated into Latin, German, Yiddish, French, and English, Sur me-Ra is not a straightforward denunciation of gambling but rather a dialogue between two friends, one opposed to games of chance, the other a proponent of such games, both positions well argued, accounting for its popularity. It was first published in Venice in the year בשמחה (with joy, [5]355 = 1594/95) by the Venetian press of Giovanni di Gara as an anonymous tract on the evils of gambling, Modena initially choosing to be anonymous. Sur me-Ra was republished, not long afterwards, twice, according to several bibliographic sources, in 1615. One edition, attributed to a Venice press, appears to be dubious, it not being recorded in any library collection and the sources that list it do so without descriptive details.[40]

The two 1615 Prague editions are recorded in a library listing, one published at the press of Moses ben Bezalel Katz, octavo in format, here consisting of ten unfoliated leaves. The second Prague edition, a bi-lingual Hebrew-Latin edition, is not so much dubious as mislabeled, having been printed several decades later and elsewhere. The Katz edition has an introduction from R. Jacob ben Mattias Treves which concludes “And it came to pass, because the midwives feared God, that he made them houses” (Exodus 1:21) at a goodly בשע”ה (375 = 1615) time, “a time to cast להשלי”ך (75 = 1615) away stones” (cf. Ecclesiastes 3:5).

A bi-lingual Hebrew-Latin edition of Sur me-Ra was purportedly printed in Wittenburg in 1665 by Johannis Haken. This edition is physically small, octavo in format, measuring 18 cm.; otherwise it is an expanded edition of Sur me-Ra, being comprised of [134] pp. and ending on quire Q3 followed by several index pages. There is a Latin title-page with a Hebrew heading, giving the place of printing, printer’s name, and date, followed by considerable preliminary matter in Latin. There is a second Hebrew-Latin title page, lacking all of these particulars about the edition and with a somewhat dissimilar briefer Latin text.

This Wittenburg edition of Sur me-Ra has been incorrectly recorded in at least one major library as a second 1615 Prague Hebrew-Latin edition of that work. The reason for the error appears to be twofold. First, the library copy lacks the first descriptive title-page and the second title page, as noted, lacks identifying information. Moreover, the introduction to the Prague edition is included, with its reference to Prague at the beginning and, at the end, two highlighted dates, although the first “at a goodly בשע”ה (375 = 1615) time” is not highlighted here and a close reading indicates that the second date was set improperly, that is, the Prague edition which concludes with the date “a time to cast להשלי”ך (375 = 1615)” here, reading להשלי”ך, the final khaf being emphasized as if to be included in the enumeration of the letters, which likely misled a reader looking at it too casually, as it results in a figure (395) too large for the Prague edition and too small for the Wittenburg edition.[41]

Another edition of Sur me-Ra was printed in Leiden by Johannes Gorgius Nisselius. An orientalist, Nisselius, poor and unable to obtain a post as a teacher, became a printer. The title-page is misdated תנ”ו (456 = 1696) instead of 1656, attributed by L. Fuks and R. G. Fuks‑Mansfeld to Nisselius’ unfamiliarity with Hebrew chronology, and causing Moritz Steinschneider to describe it as an “edition negligenitissime curate (a very slipshod edition).[42]

Three reported bi-lingual editions of Sur me-Ra, Hebrew with Latin translation, quarto format, are recorded in bibliographic sources. The dates given are 1698, 1702, and 1767. These editions are listed, without further details, in Julius Fürst’s Bibliotheca Judaica, Benjacob’s Otzar ha-Sefarim, and Vinograd’s Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book, each likely repeating the entries in the previous earlier work.[43] That three editions of Sur me-Ra were printed in Oxford within this time frame seems highly unlikely, given that from the first Hebrew book reported for Oxford, Maimonides’ commentary on Mishnayot, with Latin, printed in 1655, concluding with a Bible in 1790, only sixteen titles with Hebrew text are reported. One printing of Sur me-Ra seems reasonable, two less so, three unlikely.

VI

Mispronunciations and misunderstandings are the source of numerous errors, a problem that persists from biblical times, as in the following passage from Judges (12:36)

And the Gileadites took the passages of Jordan before the Ephraimites; and it was so that when those Ephraimites who had escaped said, Let me cross over; that the men of Gilead said to him, Are you an Ephraimite? If he said, No; Then said they to him, Say now Shibboleth; and he said Sibboleth; for he could not pronounce it right. Then they took him, and slew him at the passages of Jordan; and there fell at that time of the Ephraimites forty two thousand.

R. David Cohen observes that not all typesetting errors can be attributed to the compositor selecting the wrong letters. In Kuntres ha-Akov le-Mishor: le-Taken ta’uyot ha-Defus shel ha-Shas Hotsa’at Vilna he observes that there are mistakes that can only be attributed to hearing. Many printers realized that it was possible to save hours of labor by having type set by a pair of workers, one reading to the setter, who either did not hear correctly or misunderstood due to different dialects. Cohen provides several examples from the 1880-86 Vilna Talmud, for example, פסח in place of פתח, and comments that much ink has been has been spent resolving apparent difficulties that are in reality nothing more than printers’ errors. Among the numerous examples are:[44]

Rosh HaShanah 14a: Rashi בקוביא (dice-playing) – a piece of עצם (bone) . . . other reading עצים (wood).

Megillah 14a: Many prophets arose for Israel מי-הוה, (it should say מיהוי) [double the number of [the Israelites]

who came out of Egypt].

Zevahim 48a: Rashi Midrasha – (Leviticus 4) . . . Should say 6.

Similarly, R. Menahem Mendel Brachfeld (Brakhfeld, 1917-84), in his two volume work, Yosef Halel, based on the Reggio di Calabria (1475) and other early editions, provides a lengthy listing of emendations to current texts of Rashi. He informs that numerous errors in more recent editions of Rashi are due to errors in transmission, frequently compounded by editors, printers, and the unkind modifications of censors. Indeed, R. Solomon Alkabetz, the grandfather of the eponymous author of Lekhah Dodi, in his edition of Rashi’s Torah commentary (Guadalajara, 1476), admittedly corrected it according to his own reasoning. Furthermore, explanations of Rashi are often based on these faulty editions.[45] At the beginning of each volume are the detailed emendations and at the end a brief summary of the changes, for example:

Leviticus 10: 16) The goat of the sin-offering, the goat of the additional service of the month and the three goats of sin-offering sacrificed on that day, the he-goat, the goat of Nahshon, and the goat of [Rosh Hodesh], etc. According to this version it is not clear what Rashi is suggesting by the he-goat. In the first edition (Reggio di Calabria) and the Alkabetz edition, the text is three goats of sin-offering sacrificed on that day, take a he-goat and the goat of Nahshon, etc. and with this Rashi alludes to the verse at the beginning of the parasha that speaks about the obligatory offerings of the day, writing take “a he-goat.”[46]

Leviticus 26: 21) Sevenfold according to your sins, seven other punishments, etc. Seven שבע is in the feminine,

and others ואחרים is male. In the first edition and in the Alkabetz edition the text is seven other punishments, as the number of your sins חטאתיכם.[47]

Our text

16) the he-goat, the goat of Nahshon, and

the goat of [Rosh Hodesh].

21) Sevenfold according to your sins, seven other punishments,

Text first edition

16) take a he-goat and the goat (RH) of Nahshon, the goat of Rosh Hodesh.

21) seven other punishments as the number of your sins.[48]

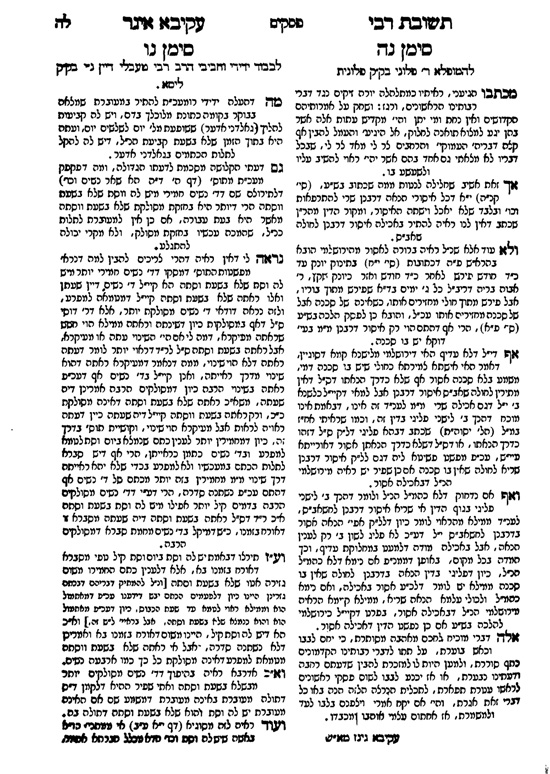

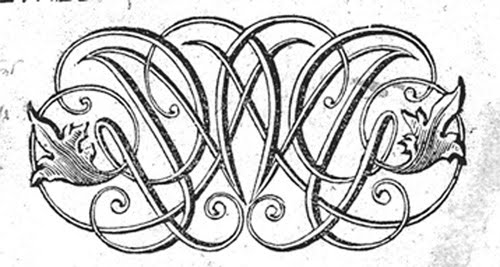

Another, quite different, inadvertent, error is of interest. In the late seventeenth- early eighteenth century a small number of printers of Hebrew books employed monograms, formed from the Latin initials of the Hebrew printer’s name, as their devices. Several were mirror-image monograms, which can be read directly and in reverse (mirror) image, resulting in more attractive and certainly more complex pressmarks than the simple interlacing of letters; perhaps graphic palindromes.[49] They are, however, often difficult to interpret; the undiscerning reader is often unaware that the mark is a signet rather than an ornamental device.

Gottschalk device correct usage – Frankfort am Main

Gottschalk device inverted – Zolkiew

The first usage of a monogram in a Hebrew book is that of the Frankfurt-am-Oder printer, Michael Gottschalk, noted above. Over several decades his mirror-image monogram appears in all of his Talmud editions, in three forms, all consisting of Gottschalk’s initials interwoven in straight and mirror images (MG), that is, it can be read in straight and reverse images. The last of his mirror-image monograms, employed on the title-pages of the Berlin and Frankfurt an der Oder Talmud editions (1715‑22, 1734‑39) is an elongated form of his initials. Gottschalk’s place in Frankfurt was taken by Professor F. Grillo, who, in association with the Berlin printer Aaron ben Moses Rofe of Lissa, completed the third Talmud. The printer’s device on the title pages of this edition is the elongated Gottschalk Mirror-monogram. It is correctly placed on most tractates but inverted on tractate Niddah. The error was quickly corrected, for on the title page of Seder Tohorot, printed immediately after and bound with Niddah, the monogram is right side up. We also find the elongated Gottschalk monogram, inverted, employed in Zolkiew on the title-page of the responsa of R. Saul ben Moses of Lonzo’s Givat Shaul (1774) by David ben Menahem, who, in this instance, likely did not realize that it was comprised of Gottschalk’s initials.[50]

At the beginning of the article it was stated that “this article is concerned with errors in and about Hebrew books only.” While the following example might tend to belie that statement, that is so only if the reader does not accept that the Bible is a Hebrew book, even if in translation. With that caveat, we bring an interesting and, from the printer’s perspective, an especially unfortunate error. For centuries the King James Bible was the authoritative English translation of the Bible by and for English speaking non-Jews. First published in 1611 by Robert Barker, it was reissued in 1631 by Barker, together with Martin Lucas, then the royal printers in London. This edition of the King James Bible is now best known as the Wicked Bible, but is also referred to as the Adulterous Bible or Sinners’ Bible. The error is in the Ten Commandments, in which the prohibition against adultery (Exodus 20:14; Heb. Bible 20:13) reads “Thou shalt commit adultery,” the “not” having been omitted, thus accounting for this edition of the King James Bible being referred to as the wicked Bible.

King Charles I was made acquainted with the error and the printers were called before the Star Chamber, where, upon the facts being proved, the printers were fined £3,000 about 34,000 pounds today). Subsequently, Barker and Lucas lost their printer’s licenses. The Archbishop of Canterbury, angered by the mistakes in this edition of the Bible, stated:

I knew the tyme

when great care was had about printing, the Bibles especially, good compositors

and the best correctors were gotten being grave and learned men, the paper and

the letter rare, and faire every way of the beste, but now the paper is nought,

the composers boyes, and the correctors unlearned.[51]

Printed in a press run of 1,000 copies, the wicked Bible was subsequently ordered destroyed; a handful of copies only are extant today.[52]

Who can discern his errors? Clean me from hidden faults. Keep back Your servant also from presumptuous sins; let

them not have dominion over me; then shall I be blameless, and innocent of great transgression (Psalms 19:13-14).[53]

[2] William

Popper, The Censorship of Hebrew Books (New York, 1899, reprint New

York, 1968), pp. 59, 60.

[3] “Who can

discern his errors? Misdates, Errors, and Deceptions, in and about Hebrew

Books, Intentional and Otherwise” Hakirah: The Flatbush Journal of Jewish

Law and Thought 12 (2011), pp. 269-91, reprinted in Further Studies in the Making of

the Early Hebrew Book (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2013), pp. 395-420.

[4] Heinrich

Graetz, History of the Jews IV (Philadelphia, 1956), p. 589.

[6] Despite having a more accurate text than later seventeenth

and eighteenth editions, the Benveniste Talmud is, with exceptions, not always

highly regarded due to its small size. An

interesting early example of this relates to the handsome Lublin Talmud

(1617-39), from the perspective of the seventeenth century. In correspondence

between a representative of Duke Augustus the Young of Braunschweig [1635-66], founder

of the Ducal Library in Wolfenbuettel and R. Jacob ben Abraham Fidanque, author

of a super-commentary on the Abarbanel’s commentary on Nevi’im Rishonim and a dealer,

Fidanque writes “My lord’s letter arrived today, Wednesday, Erev Rosh Hodesh

Tevet, concerning the Lublin edition of the Talmud. I have one to sell, and it

is very fine in its beauty and its paper, in sixteen volumes and new. If my

lord wishes to give me 40R, that is, forty R. I will send it to him immediately

upon receipt of his response. I will sell it for less, but if my lord wants to

purchase an Amsterdam edition I will sell it for 14R. . . .” (K.

Wilkelm, “The Duke and the Talmud” Kiryat Sefer, XII (1936), p. 494

[Hebrew).

[10] A somewhat inconsistent exception is

the Soncino translation of the Talmud. In the edition of Sanhedrin

published by the Traditional press (New York, n. d.) the Ben Satda entry is

omitted from both the Hebrew and English text. However, in the Judaic

and Soncino Classic Library (Judaica Press, Brooklyn, NY) edition, translator

David Kantrowitz, the Ben Satda entry is

available in Hebrew but not in English. However, in the Rebecca Bennet

Publications (1959) Soncino edition of Shabbat and the Judaic and

Soncino Classic Library edition of that tractate the Ben Satda text appears in both the Hebrew and in the English

translation, as well as in the Art Scroll Schottenstein edition of Shabbat.

That entry, however, is incomplete, and the Hebrew portion of the Judaic

and Soncino Classic Library edition notes that the censor has removed part of

the text.

[11] Abraham

Saba rewrote Zeror ha-Mor in Portugal from memory, having lost his writings

after the expulsionof the Jews from Spain.. Saba was imprisoned in Portugal for

refusing to accept baptism. Eventually released, he resettled in Morocco. Less

well known is what occurred afterwards. R. Hayyim Joseph David Azulai (Hida,

1724–1806) informs that Saba, after residing in Fez for ten years, traveled to

Verona, Italy. En route, a storm arose. The captain, in despair, requested Saba

pray for the ship’s safety. He agreed, but on the condition that, if he were to

die at sea, the captain should not bury him at sea, but rather take him to a

Jewish community for proper burial. The captain agreed, Abraham Saba’s prayed

and the storm abated. Two days later, on the eve of Yom Kippur, Saba died. The

captain took his body to Verona, where the Jewish community buried him with

great honor. (Hayyim Joseph David Azulai, Shem ha-gedolim ha-shalem with additions by Menachem Mendel Krengel

I (Jerusalem, 1979), pp. 13-14 [Hebrew].

[12] Amnon

Raz-Krakotzkin, The Censor, the Editor, and the Text: the Catholic

Church and the Shaping of the Jewish Canon in the Sixteenth Century,

translated by Jackie Feldman (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Press, 2007), pp. 142. My edition of Zeror ha-Mor,

published by Heichel ha-Sefer (Benei Brak,1990) includes this passage.

[13] Among other censored halakhic works are R. Menahem ben Aaron ibn

Zerah’s (c. 1310-1385) Zeidah la-Derekh (Ferrara, 1554). The entry in Zeidah

la-Derekh on malshinim (slanderers, informers), comprising almost an

entire leaf, was removed and the enumeration of the prayers comprising the Amidah

was correspondingly adjusted when the second edition (Sabbioneta, 1567) was

printed. The expurgated material has not been restored in subsequent editions. Another

contemporary halakhic work that was also censored is R. Isaac ben Joseph

of Corbeil (d. 1280) of the Ba’alei Tosafot’s Amudei Golah (Cremona,

1556), in which objectionable terms, and occasionally entire paragraphs, were

either substituted or suppressed. Concerning Zeidah la-Derekh and Amudei

Golah see my “Concise and Succinct: Sixteenth Century Editions of Medieval

Halakhic Compendiums,” Hakirah: The Flatbush Journal of Jewish Law and

Thought 15 (2013), pp. 122-24 and 114-16 respectively.

[14] Isaiah

Sonne, “Expurgation of Hebrew Books,” in Hebrew Printng and Bibliography, Editor

Charles Berlin (New York, 1976), p. 231.

[15] Jacob S. Levinger, “Ganzfried, Solomon ben Joseph,” Encyclopaedia

Judaica. Ed. Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 7 (Detroit, 2007),

379-380.

[16] Marc B.

Shapiro, Changing the Immutable: How Orthodox Judaism Rewrites its History

(Oxford, Portland, 2015), p. 85-89.

[19] 1575, Birkat

ha-Mazon, Lublin – Birkat ha-Mazon, facsimile reproduction

(Brooklyn, 2000), with introductions by Dovberush Weber and Eliezer Katzman,

pp. 6-23, 1-10 [Hebrew].

[21] Geoffrey Wigoder, “Abraham Bar Ḥiyya,” EJ 1, pp. 292-294.

[22] Hayyim Dov Chavel, “Kitvei Rabbenu Baḥya (Jerusalem, 1970), pp. 213-14 [Hebrew]. These remarks

are preceded by Chavel in the introduction to Kitvei Rabbenu Baḥya (p.

13), where he writes similarly that “the entire commentary on Jonah (in the

essay on Kippurim) is from this author (R. Abraham

ben Ḥayya). It is not clear to me why he concealed his name. Perhaps the reason

is that his books were very well known. . . .”

[23]

Besamim

Rosh was briefly referred to in “Who can discern his errors? . . .” in

footnote (25). It is addressed here in greater detail.

Besamim Rosh has

been the subject of considerable interest. A sample biography includes the

following: Raymond Apple, “Saul Berlin (1740-1794) – Heretical Rabbi,”

Proceedings of the Australian Jewish Forum held at Mandelbaum House, University

of Sydney, 8-9 February 2004,

Mandelbaum Studies in Judaica 12,

published by Mandelbaum House,

here; Samuel

Joseph Fuenn,

Kiryah Ne’emanah (Vilna, 1860). pp. 295-98 [Hebrew];

Reuben Margaliot, “R. Saul Levin Forger of the book ‘Besamim Rosh’,”

Areshet,

ed. Isaac Raphael, (1944) pp. 411-418 [Hebrew]; Moses Pelli, The age of

Haskalah, (Lanhan, 2010) pp. 171-89;

idem., “Intimations of Religious

Reform in the German Hebrew Haskalah Literature” Jewish Social Studies 32:1

“(Jan. 1970), pp. 3-13); “No Besamim in this Rosh,”

On the Main Line May

12, 2007,

here; Dan

Rabinowitz, “Besamim Rosh,” The Seforim Blog, October 21, 2005,

here;

Moshe Samet, “The Beginnings of Orthodoxy,”

Modern Judaism, 8: 3

(1988), pp. 249-269;

[24] Abraham

David, “Berlin, Saul ben Ẓevi Hirsch Levin,” EJ 3, 459-460.

[27] Talya

Fishman suggests that Berlin selected di Molina because little was known about

him and “it is probably of significance that this halakhist was ridiculed by

the

Shulhan arukh’s (

sic) author as one who failed to understand

the teachings of his predecessors and who said things of his own opinion, as if

‘prophetically, with no basis in Gemara or

poskim [i.e. decisors]’.

Halakhically erudite readers of

Besamim Rosh who learned that it was discovered

and compiled by R. Isaac di Molina might not have suspected the volume’s

dubious provenance, but they might well have been negatively prejudiced in

their assessment of its reliability as a legal source.” (Talya Fishman,

“Forging Jewish Memory,

Besamim Rosh: and the Invention of

Pre-Emancipation Jewish Culture” in

Jewish History and Jewish Memory: Essays

in Honor of Yosef Hayyim Yerushalmi, ed.

Elishiva

Carlebach,

John

M. Efron,

David

N. Myers, pp. 78). Zinberg (p. 197) suggests that this

di Molina is a fabricated person, noting that the

gematria

(numerical value) of di Molina equals di Satanow,

(137), a

maskilic collaborator of Berlin.

[29] Azulai, Shem

ha-Gedolim II, p. 34 no. 127.

[33] Shmuel Feiner, The

Jewish Enlightenment, tr. Chaya Naor (Philadelphia, 2011), p. 336.

[34] Mozes

Heiman Gans, Memorbook. History of Dutch Jewry from the Renaissance to 1940

with 1100 illustrations and text (Baarn, Netherlands, 1977), p. 140.

[35] Concerning

Moses Benjamin Wulff see Marvin J. Heller, “Moses Benjamin Wulff – Court Jew in

Anhalt-Dessau,” European Judaism 33:2 (London, 2000), pp. 61-71,

reprinted in Studies in

the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (hereafter Studies, Brill, Leiden/Boston,

2008), pp. 206-17.

[38] The left

image is courtesy of Israel Mizrahi, Mizrahi Book Store.

[39] For a more detailed discussion of Leon (Judah Aryeh) Modena and Sur

me-Ra see my “Sur me-Ra: Leone (Judah Aryeh) Modena’s Popular and

Much Reprinted Treatise Against Gambling” (Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, Mainz,

2015), pp. 105-22).

[40] Isaac Benjacob,

Otzar

ha-Sefarim: Sefer Arukh li-Tekhunat Sifre Yiśraʼel Nidpasim ṿe-Khitve Yad (Vilna, 1880), p. 419,

samekh 314 [Hebrew];

Ch. B. Friedberg,

Bet Eked Sefarim,

(Israel, n.d.),

samekh

331 [Hebrew]; Yeshayahu Vinograd,

Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of

Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469

through 1863 II (Jerusalem, 1993-95), p. 266 no. 1084 [Hebrew].

[42] L. Fuks

and R. G. Fuks‑Mansfeld, Hebrew Typography in the Northern Netherlands 1585

– 1815 (Leiden, 1984-87), I pp. 47-48 no. 53; Moritz Steinschneider, Catalogus Liborium Hebraeorum in Bibliotheca

Bodleiana (CB, Berlin, 1852-60), no. 5745 col. 1351:24.

[43] Isaac Benjacob,

Otzar ha-Sefarim, p. 419, samekh

317 [Hebrew]; Julius Fürst, Bibliotheca Judaica: Bibliographisches Handbuch

der Gesammten Jüdischen Literatur . . .II (1849-63, reprint Hildesheim,

1960), p. 384; Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. II pp. 14-15 nos.

6, 8, 15.

[44] David

Cohen, Kuntres ha-Akov le-Mishor: le-Taken ta’uyot ha-Defus shel

ha-Shas Hotsa’at Vilna (Brooklyn, 1983), pp. 4, 18, 22, 40.

[49] A

palindrome is a word, line, verse, number, sentence, etc., reading the same backward as forward, for example, Madam, I’m Adam; able was I ere I saw Elba; and mom.

[50] Concerning

the usage mirror-image monograms see Marvin

J. Heller, “Mirror-image Monograms as Printers’ Devices on the Title

Pages of Hebrew Books Printed in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” Printing

History 40 (Rochester, N. Y., 2000), pp. 2-11, reprinted in Studies, pp. 33-43. The

title-page of Givat Shaul, as does other of works printed in various

locations, as noted above, states that it was printed, in Zolkiew, in small

letters, with fonts, again small letters, and then Amsterdam, in a very large

font.

[52] A copy was

recently offered for sale for $99,500.

here.

Among other errors in early editions of the Bible are the “Cannibal Bible,”

printed at Amsterdam in 1682, with the sentence “If the latter husband ate her

[for

hate her], her former husband may not take her again” (Deuteronomy

24:3); a 1702 edition has the Psalmist complaining that “printers [

princes]

have persecuted me without a cause” (Psalm 119:161); and an edition published in Charles I’s reign,

reads “The fool hath said in his heart there is a God” (Psalm 14:1)

here.

[53] Having pointed out the errors of others, I thought, in

all fairness, to note some errors in my own work, both those of consequence and

those less so. Those errors, however, in both categories, being too numerous,

might, given the length of this article, prove excessive and tedious for the

reader. They need, therefore, to be saved for a later day, for a possible

future article.