Translations of

Rabbi Judah Halevi’s Kuzari

by Daniel J. Lasker

Daniel J. Lasker is Norbert Blechner Professor of Jewish Values at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, in the Goldstein-Goren Department of Jewish Thought. He has published widely in the fields of medieval Jewish philosophy, the Jewish-Christian debate, and Karaism.

This is Professor Lasker’s third essay at the Seforim

blog.

On the occasion

of the publication of:

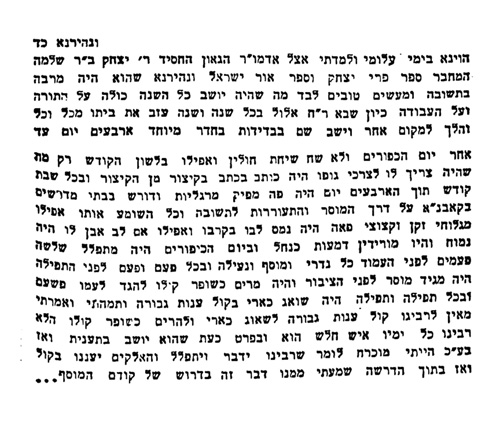

ספר הכוזרי. הוא ספר הטענה והראָיה לדת

המושפלת לרבי יהודה הלוי

תרגם מערבית-יהודית לעברית בת זמננו

מיכאל שוַרץ

הוצאת הספרים של אוניברסיטת בן-גוריון

בנגב, באר-שבע, תשע”ז

R. Judah Halevi,

The Book of Kuzari. The Book of Rejoinder and Proof of the Despised Religion,

translated by Michael Schwarz

Beer Sheva, 2017

The

publication of Prof. Michael Schwarz z”l’s new modern Hebrew translation of

Rabbi Judah Halevi’s Judaeo-Arabic Book of Kuzari provides a good

opportunity to discuss previous versions of this seminal book of Jewish thought

and to evaluate the advantages that Prof. Schwarz’s translation has over other

renditions. Prof. Schwarz (1929-2011), who completed a draft translation before

he died over five years ago, was a scholar of Jewish and Islamic philosophy

whose best-known publication has been his translation of Maimonides’ Guide

of the Perplexed. After an unfortunate delay, the Kuzari has now been

published by the International Goldstein-Goren Center for Jewish Thought at

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, in its series “Library of Jewish Thought,”

under the editorship of Prof. Haim Kreisel.[1]

Less

than thirty years after R. Judah ben Samuel Halevi completed his

Book of

Kuzari[2] in approximately

1140, it became one of the first Judaeo-Arabic compositions to be translated

into Hebrew. This pioneering translation marked part of the cultural transfer

of Andalusian Jewish culture, written in Judaeo-Arabic, into Hebrew, and was accomplished

in 1167 by R. Judah ben Saul Ibn Tibbon, “the father of the translators.” As

the centers of Jewish intellectual life moved to Christian areas where Hebrew

was the predominant Jewish literary language, it was only through this

translation that the

Kuzari was known to generations upon generations of

Jews. The

Kuzari’s readers were moved by its unwavering defense of

Judaism, its description of Jewish singular chosenness, and its love of Zion.

Halevi’s life story, including his departure from Iberia and, according to

legend, his martyrdom at the gates of Jerusalem, only strengthened the

resonance of the book (on this legend, see

here). Extensive commentaries were written on the basis of the

Ibn Tibbon translation by authors who neither understand Arabic nor were able

to appreciate the Islamic context in which the

Kuzari was written. Judah

Halevi’s defense of Judaism made a great impact on Jewish thought and achieved

canonical status.[3]

With

the birth of Jewish studies in the nineteenth century, scholars began

publishing original texts in academic editions. Thus, Hartwig Hirschfeld

(1854-1934), working with Oxford-Bodleian Ms. Pococke 284, the only complete,

or almost complete, version of the work, produced a first edition of the

original Judaeo-Arabic text of the Kuzari.[4] He published with it a

version of the Ibn Tibbon translation which was partially corrected to

correspond to the Judaeo-Arabic version, but not in a consistent manner. Thus,

Hirschfeld changed some passages in the Hebrew despite their being attested in

all the Ibn Tibbon manuscripts and editions, but left other problematic

passages untouched.[5] The Hirschfeld Ibn Tibbon text achieved wide

distribution when it was used by Avraham Zifroni as the basis of his edition of

the Kuzari, and many contemporary editions of the Hebrew Kuzari

are based on Zifroni’s work.[6] Meanwhile, Hirschfeld’s Judaeo-Arabic publication

has been supplanted by the superior edition of David Zvi Baneth and Haggai

Ben-Shammai.[7]

The

Judah Ibn Tibbon translation of the Kuzari is an adequate translation, despite

some misunderstandings. It follows the Tibbonide practice of maintaining the

syntax and word order of the original Arabic to the extent possible and often

translating the same underlying Arabic term with one Hebrew equivalent. It may also

be a better witness to the original text of the Kuzari than the unique Judaeo-Arabic

manuscript which was copied in Damascus over 300 years after the composition of

the original book. For professional students of medieval Jewish philosophy, or

those with close familiarity with medieval Hebrew, it is readable and achieves

its goal of making the work accessible to non-Arabic readers. Yet, there is

still no acceptable edition based on the best manuscripts of this translation.

In addition, as a means of communicating the extent of Judah Halevi’s thought

to the contemporary reader of modern Hebrew, it is less than ideal. Thus, since

the 1970’s, a number of new Hebrew translations of the Kuzari have

appeared.

The

first of these translations was presented by Dr. Yehudah Even Shmuel (1886-1976)

in 1973.[8] The first edition included a long introduction, a vocalized and

punctuated text, short notes and many extensive indices, and was praised for

the clarity of its Hebrew and its accessibility to contemporary readers.

Subsequently it was published in paperback with just the text and short notes,

an edition which has sold well and is used as a textbook for high schools and

universities. At first, the novelty of a medieval philosophical work in

readable modern Hebrew seems to have compensated for the imprecision of the

translation.[9] Oftentimes, the translator offered more of a creative

paraphrase than an exact translation, and there were sections where Even Shmuel

attempted to tone down considerably Judah Halevi’s view of Jewish essentialism.[10]

Many key terms were translated by different Hebrew words, making it impossible

for the reader to note the importance of these words, most of which have

resonances from the Islamic and Arabic realms. Thus, Halevi’s great debt to his

non-Jewish cultural context was effectively hidden by this translation.

Scholars soon realized that this edition of the Kuzari could not be used

for academic purposes.

Despite

its drawbacks, or perhaps because of its advantages, the Even Shmuel

translation went unchallenged for over 20 years. In the mid-1990’s, I heard

Rabbi Yosef Kafiḥ (1917-2000), the well-known editor and translator of

Judaeo-Arabic texts, reply to a question as to why he did not translate the Kuzari

as he had translated so many other classics. He responded that he had prepared

such a translation many years previously but had decided not to publish it

because he did not want to appear as competing with Even Shmuel. Nonetheless, Kafiḥ

finally did publish his own translation in 1997,[11] following his custom of

presenting the original Judaeo-Arabic and the Hebrew translation in parallel

columns.[12] This translation has neither the clarity nor the extensive

notation of Kafiḥ’s earlier translations; most of his comments are devoted to

attacking Even Shmuel’s translation. In his introduction, Kafiḥ explains that

he had begun translating the Kuzari when he was a student in a class led

by Rabbi David Cohen (the Nazir, 1887-1972) at Merkaz Harav Yeshiva in 1947-48,

where he was made responsible for comparing Ibn Tibbon’s Hebrew with the

Judaeo-Arabic in the Hirschfeld edition.[13] Repeating what he had said in

public, namely that he had waited so long to publish this translation because

of his desire not to appear as a competitor with Even Shmuel, he then goes on

to attack Even Shmuel’s translation mercilessly. He even states that Rabbi

Judah Halevi composed one of his dirges when he realized that his Kuzari

would be translated by Even Shmuel.

Despite

Rabbi Kafiḥ’s great erudition in Judaeo-Arabic, and the general readability of

his other translations, the Kuzari does not match his previous work.

Whether this was a result of the fact that the translation was, indeed, a

product of his youth before he had perfected his Hebrew style, or was the work

of an aged man who did not review his earlier drafts, it did not succeed in replacing

the Even Shmuel translation as the generally accepted Hebrew version of the Kuzari.

My own experience with Israeli students has been that Kafiḥ’s Hebrew is not

much more understandable than that of Judah Ibn Tibbon, and, despite the

convenience of having the original Judaeo-Arabic text available, it was not a

very good pedagogical tool. Sometimes I preferred using the Ibn Tibbon text

which is available in a number of formats, such as in Yediot Aharonot’s Am

ha-sefer project[14] and on-line.

There

exists one more contemporary translation of the Kuzari into Hebrew and

that is the one produced by Rabbi Itzhak Shailat (b. 1946).[15] Shailat is

known for his editions and translations of medieval Judaeo-Arabic texts, such

as Maimonides’ Epistles. Although Shailat’s introduction and notes to

his editions demonstrate a conservative, harmonistic and pietistic approach to

his authors, his translations are generally accurate. His methodology, however,

is to reproduce Tibbonide Hebrew as much as possible, giving his translations a

classical, rather than modern, feel. Hence, his Kuzari should be seen as

an update of Ibn Tibbon rather than as an independent creation.

Before

discussing the new Hebrew translation, it might be useful to refer to

translations into other languages. In addition to editing the Judaeo-Arabic

text of the Kuzari, and producing an edition of Ibn Tibbon’s Hebrew

translation, Hartwig Hirschfeld also translated the book into English.[16] This

work was reissued many times, often with minimal attribution to Hirschfeld.[17]

The abridged translation of the Kuzari by Prof. Isaac Heinemann

(1876-1957) which appeared independently in Oxford, 1947, and was later

incorporated in the widely distributed Three Jewish Philosophers,[18] is

greatly dependent upon Hirschfeld. In addition to questions of accuracy, the

language of these translations is difficult for the contemporary English

reader.

In

an attempt to present a clearly written English version of the Kuzari

which could be used by laypeople, Rabbi N. Daniel Korobkin (b. 1964) published

a translation on the basis of the Ibn Tibbon version, relying on the

interpretations of the classical commentators Judah Moscatto and Israel of

Zamosc.[19] Although achieving its goal of readability, the author’s ignorance

of Arabic and the scholarly literature on the Kuzari are the cause of

multiple errors of translation and annotation. Ibn Tibbon’s Hebrew translation

of the Kuzari is included in the book, but since it is based on the

Hirschfeld/Zifroni edition (the exact source is not noted in the book), and the

English translation is based on older editions, there are inconsistencies

between the Hebrew and the English. Subsequent to the Korobkin translation, other

English editions of the Kuzari have appeared, but apparently none of them

is based on the Judaeo-Arabic original.[20]

A

scholarly, readable English translation of the Kuzari from the original

has long been a desideratum. In fact, Prof. Lawrence V. Berman (1929-1988)

began the work on such a translation before his untimely death. The project was

inherited by Prof. Barry S. Kogan (b. 1944) and is scheduled to appear as part

of the Yale Judaica Series. This project has been long delayed, but Prof. Kogan

has been very generous with sharing drafts of this translation with colleagues,

a number of whom have used its clear and accurate renditions in their own

publications. One can only hope that there will not be much further delay until

the translation appears in print.[21]

This

leads us to the recently published Hebrew translation of the Kuzari by

Prof. Michael Schwarz. Following the pattern established in his translation of

Maimonides’ Guide, Schwarz presents an eminently readable rendition of

the book. As in the case of his other translations, the work combines accuracy

with readability. His language is elegant, eschewing the many foreign words

which have entered contemporary Hebrew. He highlights words which appear in

Hebrew in the Judaeo-Arabic original by using a bold font so the reader knows

that this is Halevi’s Hebrew, not Schwarz’s.

As

noted above, one of the challenges with a translation of the Kuzari is

how to capture the Islamic/Arabic flavor of the work. Despite its reputation as

the most Jewish of the medieval Jewish philosophical treatises, recent research

has demonstrated the extent to which the Kuzari is steeped in Islamic concepts.[22]

This can be seen by its use of a number of key terms which are repeated

throughout the book, such as ṣafwa (the choicest, translated as segulah,

as found in other translations, despite Prof. Schwarz’s reservations); al-amr

al-ilāhī (divine order, translated ha-davar ha-‘elohi, as per Kafiḥ,

in contrast to Ibn Tibbon’s ha-ʿinyan ha-‘elohi); ijtihād (fervent

striving or innovating new laws, translated as hit’amẓut, hishtadlut, or ḥiddush

halakhah), or qiyās (analogous reasoning or general rationalism,

translated heqesh or higgayon). Since it is not always possible

to use the exact same translation in every context, the translator must find a

way of informing the reader of the underlying key term. Schwarz solves this

problem by drawing up a list of recurring Arabic concepts and noting each time

one of them is used. He then explains these terms in a special glossary devoted

to their explication. Some important Arabic words which are used less often are

explained in the textual notes. In addition, the notes provide references to

Halevi’s sources or further explications.

Scholarly

analyses of the Kuzari are extensive, and as in the case of Schwarz’s

translation of the Guide, the notes are full of references to this

secondary literature. Although he does not say so in his very short preface,

one can assume that as was the case in the Guide, the reference to a

particular article or book does not necessarily imply endorsement of the

material found therein. The annotations are there for comprehensiveness, and

the alert reader is enjoined to examine them carefully. The bibliography

occupies 36 pages. In addition, there are indices of sources and a general

index of topics and places.[23]

When

Part One of Prof. Michael Schwarz’s translation of the Guide was first published

by Tel-Aviv University Press in 1997, I offered the opinion that despite the

fact that it was the best available Hebrew version of Maimonides’ masterpiece,

I was not sure it would replace the other available translations, partially

since traditional Jewish readers might be wary of a university provenance and

the reliance on non-Jewish sources.[24] I believe that my estimation has been

proven wrong, since the translation’s clear superiority to the competition has

made it indispensible.[25] It is to be hoped that the same widespread

acceptance of the Schwarz translation of the Guide will be repeated in

the case of the Schwarz translation of the Kuzari, since it is, without

doubt, the best Hebrew Kuzari available.

Notes:

[1]

Books from this series are produced by the Mosad Bialik Publishing House. The

Schwarz

Kuzari can be ordered

here.

The translation is preceded by an introduction which Prof. Schwarz asked me to

write and which he approved a few weeks before his death. [Editor’s Note:

Professor Schwarz’ edition of the Kuzari can be purchased via Bialik or by

contacting (

Eliezerbrodt@gmail.com) — where the book will be available at the

same Book Week price. Portions of the proceeds of this sale help support the efforts of

the Seforim Blog.]

[2] The title, The

Book of Rejoinder and Proof of the Despised Religion, is in accordance with

a Geniza fragment; a slightly different title appears in the one full Judaeo-Arabic

manuscript mentioned below. The title of Ibn Tibbon’s translation, Sefer

ha-kuzari, was that which was known to centuries of Hebrew readers, and it corresponds

to the title, al-kitāb al-khazarī (“The Book of the Khazar”), found in

Halevi’s famous autograph letter from the Geniza.

[3] See Adam

Shear, The Kuzari and the Shaping of Jewish Identity, 1167–1900,

Cambridge 2008. Another medieval translation, by Judah ben Isaac Cardenal, has

not survived.

[4]

Das Buch

al-Chazarî des Abû-l-Hasan Jehuda Hallewi; im arabischen urtext sowie in

der hebräischen übersetzung des Jehuda Ibn Tibbon, herausgegeben von Hartwig

Hirschfeld, Leipzig, 1887. The manuscript is now classified as Neubauer

Catalogue Oxford ms. 1228, and it is freely available on-line (

here).

[5] See Daniel

J. Lasker, “Adam and Eve or Adam and Noah? Judaeo-Arabic and Hebrew

Versions of the Same Books,” Pesher Nahum. Texts and Studies in Jewish

History and Literature from Antiquity Through the Middle Ages Presented to

Norman (Naḥum) Golb, ed. Joel L. Kraemer and Michael G. Wechsler et al.,

Chicago, 2012, pp.141-148.

[6] The Zifroni

edition, Warsaw, 1911, published under his original name Zifrinowitsch,

included many valuable notes. Subsequent editions generally omitted these

notes.

[7] Judah

ha-Levi, Kitāb al-radd wa-ʾl-dalīl fi ʾl-dīn al-dhalīl (Al-kitāb al-khazarī),

ed. David H. (Zvi) Baneth and Haggai Ben-Shammai, Jerusalem, 1977.

[8] The

Kosari of R. Yehuda Halevi, Translated Annotated and Introduced by Yehuda

Even Shmuel, Tel Aviv, 1972. On Even Shmuel, né Kaufman, see Ira Robinson, “The

Canadian years of Yehuda Kaufman (Even Shmuel): Educator, Journalist, and

Intellectual,” Canadian Jewish Studies, 15 (2007), pp. 129-142.

[9] See, e.g.,

Michael Schwarz’s effusive review in Kiryat Sefer, 49 (5734), pp.

198-202. Many years later, Prof. Schwarz told me that he no longer held the

views he expressed in that review.

[10] For

instance, the term ṣarīḥ/ ṣuraḥa’, meaning “native-born,” and indicative

of Halevi’s essentialist view of the Jewish chosenness, is glossed over in

1:115; 2:1; and 5:23; see Daniel J. Lasker, “Proselyte Judaism, Christianity

and Islam in the Thought of Judah Halevi,” Jewish

Quarterly Review, 81:1-2 (July-October, 1990): 75-91 (Hebrew version: in Ephraim Hazan and Dov Schwartz, eds., The

Poetry of Philosophy. Studies on the Thought of R. Yehuda Halevi,

Ramat-Gan, 2016, pp. 207-220).

[11] Sefer

ha-kuzari le-rabbeinu Yehuda Halevi zẓ”l, Kiryat Ono, 5757.

[12] Kafiḥ states

that he used the text published by Hirschfeld, correcting it according to the

Baneth-Ben-Shammai edition. A comparison of texts indicates that he did not

always follow Hirschfeld and Ben-Shammai. In fact, in the edition and Hebrew

translation, he accepted certain emendations in the order of the text and the

re-assignment of sections from the King to the Sage, and vice versa, e.g.,

3:25-31. These departures from the original are very similar to ones made by

Even Shmuel (both mention the opinion of Rabbi Ben-Zion Hai Uziel).

[13] Cohen’s

class notes were published many years later as a commentary on the Kuzari

under the title Ha-kuzari ha-mevu’ar, edited by Dov Schwartz, Jerusalem,

1997.

[14] Judah

Halevi, Sefer ha-kuzari, Tel Aviv, 2008 (with my introduction). The text

is vocalized and section headings have been added (not by me), but it is not a

scientific edition.

[15] Jerusalem,

2010. In his introduction (p. 5), Shailat writes that he was aware that Prof.

Schwarz was working on a translation, but he decided to go ahead with his own

project because it was unclear when the Schwarz translation would be ready and

unlike Schwarz’s rendition into modern Hebrew, Shailat was translating it into

medieval Hebrew.

[16] Judah

Hallevi’s Kitab al Khazari, translated from the Arabic with an introd. by

Hartwig Hirschfeld, London, 1905.

[17] E.g., the

edition by Schocken Publishing House, The Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith

of Israel (various editions), which mentions H. Slonimsky as the author of the

introduction on the cover of the book, but requires one to search well to find

out that it was Hirschfeld’s translation.

[18] Cleveland,

1960, with many reprints.

[19] Yehuda

HaLevi, The Kuzari. In defense of the Despised Faith, translated and

annotated by N. Daniel Korobkin, Northvale, N.J., 1998.

[20] Amazon.com

lists many editions of the Kuzari. I have been unable to check them

personally. As far as I know, they are all dependent upon the Hebrew.

[21]

Reference should be made as well to the excellent French translation by Prof. Charles

Touati (1925-2003), executed on the basis of the Judaeo-Arabic original: Juda

Hallevi, Le Kuzari. Apologie de la religion méprisé, traduit sur le

texte original arabe confronté avec la version hébraïque et accompagné d’une

introduction et de notes par Charles Touati, Louvain, 1994.

[22] My student

Ehud Krinis discusses Shi’ite influence; see his God’s Chosen People: Judah

Halevi’s Kuzari and the Shīcī Imām Doctrine, Turnhout 2014. For Sufi influence, see Diana Lobel, Between

Mysticism and Philosophy: Sufi Language of Religious Experience in Judah

Halevi’s Kuzari. Albany, NY 2000.

[23] The indices

were produced by Prof. Schwarz’s son, David Zori, who took upon himself the

responsibility of transforming his father’s draft into publishable form.

Editorial work on the text was done by Ayal Fishler.

[24] Jewish Studies, 37 (1997): 267-271

(Hebrew).

[25] An edition

of Schwarz’s Guide, without the notes and with some corrections, was

issued by Yediot Aharonot in the Am ha-sefer series, Tel-Aviv, 2008. The

translation was also at one time freely available on-line until Tel-Aviv

University Press removed its site. Accessing it on-line is still possible, but

it is not as easy as it once was.