The Yiddish Press as a Historical Source for the Overlooked and Forgotten in the Jewish Community

Review of Kedushat Aviv: Rav Aharon Lichtenstein zt”l on the Sanctity of Time and Place

by David Strauss)

with the difficulties of the topic and to rule about matters that are subject to doubt (e.g. Shev Shemateta), and, in recent generations, the goal may be to define the concepts in depth (e.g. Sha‘arei Yosher). Rav Aharon, as a prominent scholar of the Brisker approach, belongs to the latter group. The author immerses himself in the depths of Halakha and takes advantage of his mastery of the Talmudic passages, the Rishonim, and the Acharonim (attested to by indices at the end of the volume).

We were already able to benefit from the essays published in Rav Aharon’s previous book, Minchat Aviv (here), which was previously reviewed at the Seforim blog by Professor Aviad Hacohen (here) some of which constitute comprehensive thematic studies in themselves (see, for example, his examination of the issue of “lishmah”).

The current volume, however, is an entirely new development. The scope is astounding, and the imagination and ambition are inspiring. Leafing through the main headings, most of which are dealt with at length, reveals that the book covers the major issues relating to the sanctity of time and place.

The first part deals with the sanctity of Shabbat and Yom Tov, Kiddush, the sanctity of Yom Kippur, the Sabbatical and Jubilee years, the sanctification of the months, and the intercalations of the calendar. The second part opens with the sanctity of Eretz Yisrael, and then moves on to the sanctity of walled cities, Jerusalem, the Temple Mount, and the Temple and its various parts.

In Kedushat Aviv, Rav Aharon applies the unique scholarly approach that characterizes all of his teachings in order to elucidate the topic of sanctity. We will note below several points relating to the author’s methodological approach.

The grand plan of the work allowed Rav Aharon to give free rein to the fullness of his originality. This originality stems not necessarily from flashes of brilliance, but rather from the author’s fundamental and thorough examination of the material under study.

To illustrate this, let us examine one small element of a discussion concerning the sanctity of Eretz Yisrael, a classic subject in Talmudic scholarship. The chapter opens with a review of some of the well-known doctrines, as taught by the sages of Brisk – first and foremost the distinction between the “sanctity” of Eretz Yisrael and the “name” of Eretz Yisrael. This duality regarding the unique status of the land has a number of practical ramifications, which are quite familiar to anyone at home in the beit midrash.

Thus, for example, the geographical scope of the “name” of Eretz Yisrael extends to the broad boundaries of the land conquered by those who came out of Egypt (as opposed to the narrower borders achieved by the returnees under Ezra). Also, it is never cancelled, even according to those who say that the initial sanctification of Eretz Yisrael did not hold for the future. Thirdly, it obligates only some of the commandments connected to Eretz Yisrael (for example, egla arufa, but not terumot and ma’asrot). Rav Aharon considers these classical matters and declares that “Heaven has left me room to illuminate another facet of the issue.” From here he continues with novel clarifications and further developments that greatly broaden the halakhic concept of Eretz Yisrael, as the traditional dichotomy is restrictive and there is no reason to assume that it is necessarily true.

Rav Aharon argues that in addition to the sanctity of the land of Eretz Yisrael (which obligates the setting aside of terumot and ma’asrot), we can speak of three different concepts that underlie the “name” of Eretz Yisrael:

- the chosen land in which the Shekhina rests;

- the place where the sanctity of the Temple spreads out gradually (as explained in the first chapter of Keilim), this being reflected in the laws governing the removal of the ritually impure from the camp;

- the land where the people of Israel become a united community and in which they fulfill their public duties (e.g., egla arufa).

It is, of course, possible to attribute all of these things to the “name” of Eretz Yisrael and assume that they all apply within the borders of the land conquered by those who left Egypt. But Rav Aharon writes, in his characteristic language, that “one can distinguish between the different aspects.” It is possible, for example, that the indwelling of the Shekhina sanctifies the land independently of any connection to the Temple. It is also possible that neither of these is necessary for regarding the people of Israel as a community dwelling in their own land.

This approach allows for a certain flexibility when we attempt to define the geographical entity of Eretz Yisrael. It may be argued that the covenantal boundaries of Abraham are the determining factor regarding a particular matter, but regarding a different matter, it is the boundaries mentioned in Parashat Mas’ei or the boundaries of the conquests of Yehoshua. This discussion is entirely independent of the idea of the “sanctity” of Eretz Yisrael regarding terumot and ma’asrot, which relates to the land settled by those who ascended from Bavel.

Thus, we are liberated from the fixed idea that anything unrelated to terumot and ma’asrot depends on the boundaries of the land conquered by those who left Egypt. The dichotomous approach is indeed convenient, and it may, in fact, be implicit in the words of the Rambam. However, dissociating from it is important, for example, when we discuss Transjordan. This area was certainly subject to the laws of terumot and ma’asrot during the First Temple period by Torah law, but it is referred to as an “impure land” in Scripture. From this, the Radbaz learns that in Transjordan there is “sanctity of mitzvot,” but no “sanctity of the Shekhina.” We see, then, that the sanctity of the Shekhina is not found in all places conquered by those who left Egypt, despite their possessing the sanctity of the land with respect to mitzvot. According to the conventional terminology, this situation is difficult to explain, to say the least. In this context, Rav Aharon cites the Sifre Zuta: “Transjordan is not fit for the house of the Shekhina.”

Another example relates to the sanctification of the month. It is generally assumed that the sanctity of time depends on human action, as expressed in the blessing, “Mekaddesh Yisrael veha-zemanim, He sanctifies Israel, who sanctify the appointed times.” In Rav Aharon’s chapter on the topic, this statement is treated thoroughly, systematically and in detail.

First of all, we may ask: Who is “Israel” in this context? Does it refer to a court of three, the Great Sanhedrin, the leaders of the people (“Moshe and Aharon,” according to Scripture), the nation of Israel as a collective, or the people of Israel as individuals? The fact that there are so many possibilities necessitates precision in definition, and, as mentioned above, a readiness for liberation from convenient dichotomous thinking.

As for the fundamental question, a distinction must be made between the law in practice and the law in principle; it is possible that in practice the mo’adim are determined by a court, but as representatives of the people. It must also be kept in mind that the process of establishing the mo’adim is complex and has stages that can be distinguished from one another – the deliberations, the final decision, and the actual sanctification. We may propose, for example, that in principle the decision is in the hands of the community, but the court acts on their behalf; regarding the actual sanctification, however, the court acts independently. The practical ramification is that the decision itself must be made in Eretz Yisrael (the place of the people of Israel as a national entity), whereas the actual sanctification can take place anywhere. The identity of the body that performs the actual sanctification is also a central question when it comes to exceptional situations in which human involvement is in doubt – for example, when the month is not sanctified at its appointed time, but is rather “sanctified by Heaven.” Is there still a role for the court in such a case? Rav Aharon demonstrates that this issue is subject to a dispute.

The proceeding discussion turns to the manner in which the calendar is determined in our times, in the absence of a Sanhedrin and authorized judges. Does this prove that in the end the human factor is dispensable? Once again, the answer depends upon differing opinions – whether the calendar in our day is determined in practice by the inhabitants of Eretz Yisrael (Rambam), by an earlier decision made by R. Hillel II and his court (Ramban), or “in Heaven” (Ri Migash). The Ramban’s view is ostensibly the “conservative” one, as according to him, the mechanism for sanctifying the month remains in principle as it was throughout history, with one “slight” deviation – the matter was settled long in advance. Rav Aharon, however, with his penetrating observation, discerns a great difference between projective astronomical calculations and what took place during the time of the Temple. The latter was a direct sanctification of the current month in present time, whereas the court of Hillel established a calendar as a long-term directive, which dictates the mo’adim in advance based on how they fit the pre-determined framework. Thus, it turns out that, contrary to what we might have thought, the Ramban actually agrees with the Ri Migash, and not with the Rambam, that in our time the mo’adim become sanctified on their own, without any direct sanctification on the part of the court.

The volume under discussion is unique in its creative use of biblical verses. The window to this methodology was opened wide by the founder of the Brisker approach of Talmud study, who relied heavily on the idea of “gezeirat ha-katuv,” “Scriptural decree,” beyond what is generally found in the literature of the Acharonim. As a rule, this Brisker approach demonstrates sensitivity and precision with regard to the meaning arising both from the wording and from the context of the biblical text.

For example, we mentioned earlier that Rav Aharon distinguishes between two levels of human involvement in determining the calendar: establishing a system of dates, which can be done in advance, as opposed to immediate and direct sanctification. According to the Ramban, the calendar of R. Hillel II fulfills the first component, but it lacks the direct sanctification. R. Aharon identifies these two aspects in two different passages of the Torah. In Parashat Emor, we read: “These are the appointed seasons of the Lord… which you shall proclaim in their appointed season.” This describes a “proclamation” of a calendar as a framework, which can be done on a comprehensive scale and even long in advance. In contrast, in Parashat Bo we read: “This month shall be to you the beginning of months” – the source for the sanctification of each month in its time based on a sighting of the new moon. Thus it may be suggested that in our time, according to the Ramban (as well as the Ri Migash), we fulfill the command in Emor, but we are unable to carry out what is stated in Bo. From this it may be concluded that this element is not indispensable. On the other hand, according to the Rambam, who maintains that even in our time, the sanctification of the appointed times is executed in a direct manner, we fulfill both elements – the proclamation and the sanctification.

Rav Aharon uses the same method in his comprehensive discussion of the sanctity of Shabbat and Yom Tov, with which the book opens. Here the recourse to biblical texts is more extensive and is consistently present in the discussion. This is already apparent at the beginning of the essay, which is devoted to an examination of the Torah passages dealing with Shabbat, to the distinctions between them, and to their halakhic ramifications.

Rav Aharon’s main argument is that the verses in the passage of “Ve-shamru Bnei Yisrael et ha-Shabbat” in Parashat Ki-Tisa constitute a change with respect to the discussions of Shabbat in Yitro and in Mishpatim. Parashat Ki-Tisa introduces the concept of desecrating the Shabbat, as well as the death penalty for that offense. Prior to these verses, the foundation of Shabbat lay in its being a reminder of the act of Creation, and this foundation gave rise to the melakhot as prohibited actions.

But in Parashat Ki-Tisa, the Torah presents Shabbat as a sign of the covenant and as a focus of the resting of the Shekhina, which is why these verses are found in the context of the commandment regarding the building of the Tabernacle. Only now does performing a forbidden action on Shabbat become its desecration – after it has been established that it has sanctity that is subject to desecration (just as the sanctity of the Temple is desecrated by the entry of something that is ritually impure). The liability for the death penalty is not for the performance of the prohibited labor itself, but for its consequence – the desecration of the sanctity.

Thus, there are “two dinim” regarding the sanctity of Shabbat, and the attribution of various details of the laws of Shabbat to one or the other aspect of the sanctity of the day has halakhic ramifications.

Rav Aharon further explains why the prohibited labor of kindling is mentioned separately in Parashat Vayakhel (on the assumption that there is no halakhic difference between it and any other prohibited labor, on the Tannaitic view that its specification is a mere illustration of separate culpability for each transgression of Shabbat law). Kindling is fundamentally a labor connected to food preparation, and such a labor is prohibited only because of the “covenant” aspect of Shabbat. Therefore, it could not have been prohibited before Parashat Ki-Tisa. Hence the difference in the definition of the sanctity of the day between Shabbat and Yom Tov.

We have presented here only a few fundamental ideas on which the author proceeds to expand and build entire edifices.

Much of the richness of Rav Aharon’s writings derives from his commitment to the truth. By virtue of this commitment, he avoids adherence to conventional ideas and often raises doubts about commonly accepted matters, and thus he entertains many varied possibilities. Some readers will be frustrated by the fact that so much is left in question. In their view, Torah novellae are measured according to their success in clarifying and proving from the sources the opposing sides of the various investigations – “there is no greater joy than the clarification of doubt.” However, from Rav Aharon’s point of view, the ability to maintain a conceptual space in which different possibilities are open is a source of satisfaction. According to the atmosphere of the book, successfully removing a threat to one of the options, thus “proving” that everything is still possible, is a source of relief. This tendency is expressed in phrases such as “it may be argued” or “it may be suggested.” The fact that these possibilities are not directly supported by the views of any of the Rishonim is not a reason to ignore them.

For example, according to the well-known position of the Rambam, the opinion that maintains that a gentile’s purchase of land in Eretz Yisrael cancels the sanctity of the land for the purpose of terumot and ma’asrot further argues that the exemption continues even if the land is bought back by a Jew. This is because the Jew’s purchase falls into the category of “the conquest of an individual,” as opposed to a national acquisition. Rav Aharon explains at length why this is not necessarily so, despite the ruling of the Rambam. It is possible that even according to the view that the gentile’s ownership cancels the sanctity, that sanctity returns when Jewish ownership of the land is restored.

First of all, the Rambam assumes that “the conquest of an individual” is a problem even in Eretz Yisrael itself, and not only in Syria, a matter that is subject to dispute. Second, it may be suggested that when all of Eretz Yisrael is in Jewish hands, the private purchase of a particular field joins the collective ownership and becomes part of the conquest of the community, despite the fact that the purchaser himself is interested only in his private ownership. It is further possible that even if the purchase is the conquest of an individual and it cannot sanctify the land directly, it is able to join the field to the part of Eretz Yisrael that is already holy, and thus is endowed with automatic sanctity. It is also possible that even if the gentile’s purchase of the land cancels its sanctity, it is not fully cancelled (as would be in a situation of destruction or of general foreign occupation), but is rather temporarily frozen, and it is therefore liable to reveal itself once again without another act of sanctification.

In a related matter, the author discusses the view of R. Chayim Brisker regarding the status of the laws relating to the sanctity of the land when the majority of the nation is not found in Eretz Yisrael. According to the Rambam, during the time of the Second Temple, there was no obligation to set aside terumot and ma’asrot, since there was no return of all (or most) of the people of Israel in the days of Ezra, “bi’at kulkhem.” R. Chayim explains that this deficiency is not an independent condition for obligation, but rather a deficiency in the sanctity of the land. In accordance with this understanding, he assumes that the criterion of “bi’at kulkhem” refers to the moment of the sanctification of the land (the time of Ezra’s arrival). If it fails at that point, the situation is irrevocable despite subsequent immigration.

Rav Aharon raises doubts about this in light of the Rambam’s statement, “The Scriptural commandment to separate teruma applies only in Eretz Yisrael and only when the entire Jewish People is located there,” which does not mention this limitation. Even according to R. Chayim’s fundamental assumption, Rav Aharon asks, why not consider the later joining of most of Israel to be a continuation of the conquest, despite the fact that they did not arrive in the days of Ezra? Rav Aharon then proposes a different understanding that undermines the position of R. Chayim.

It is possible that what was suggested above regarding gentile ownership is also true of gentile conquest. In other words, even at a time of destruction, the sanctity of the land is not totally cancelled, but only frozen. This is because the sanctity of the land stems from its designation as the inheritance of the people of Israel. When the people of Israel are not there, the sanctity exists in potential. The people of Israel’s realized possession of and control over the land actualizes this sanctity. It is therefore possible that what is referred to as an “act of sanctification” of Eretz Yisrael is in fact merely the fulfillment of a condition for revealing this sanctity in actuality.

Even if we do not accept this understanding concerning the sanctification of Ezra, it is possible to accept it with regard to the condition of “bi’at kulkhem.” And even if Ezra had to perform some formal act of sanctification, after him – and even in our time, when the second sanctification is still in force – we certainly do not need “bi’at kulkhem” as part of the act of sanctification, but, as stated, as a reality that actualizes the destiny of the land and reveals its full sanctity.

These musings and their like open many theoretical avenues regarding concepts of sanctification and the sanctity of Eretz Yisrael, as well as their application in practice.

What Is Sanctity

Thus far we have noted some of the scholarly qualities of the book, but attention must also be paid to its contents. Given that the book encompasses so many facets of the laws of sanctity, does it also have something important to say about the nature of sanctity in the eyes of Halakha?

The editors of the book have done us a service by appending an essay that addresses this question, and we will make use of it here to deal with the issue, however briefly. The chapters of this volume reveal a conception of sanctity that is not only multi-faceted in itself, but is the object and background for human activity that reciprocally alters its nature. The Torah does not view sanctity as a guest from another world that lands in the human-natural world and transforms its order. On the contrary, it is integrated into the life of the individual, who responds to it with reciprocity and creativity.

Sometimes a person will find himself reacting to the appearance of sanctity with a declaration and with recognition, this in order to receive and integrate it into his earthly life, but without creating a new dimension. On the other hand, a person often does add a new dimension to existing holiness, what Rav Aharon calls its human “stratum.” Another possibility is not to add a new dimension to sanctity, but to “deepen” the existing dimension. These two latter options are certainly distinct, and illustrate once again the author’s close attention to precise definition and classification.

Finally, of course, there are cases in which man’s activity is the primary source of sanctity – whether deliberately initiated or spontaneously generated. At the same time, on the negative side, we must examine the situations in which a person can cancel holiness, or desecrate and impair it without abolishing it altogether, and when existing sanctity is completely indifferent to human actions. The editors illustrate these various avenues using detailed examples from the book.

Ancient Jewish Poetry & the Amazing World of Piyut: Interview with Professor Shulamit Elizur

Just as the mountains surround Jerusalem, so G-d surrounds his people, from now to all eternity —Tehillim 125:2

This piece originally appeared in14 TISHREI 5778 // OCTOBER 4, 2017 // AMI MAGAZINE #337

Thanks to Ami for permission to publish this here.This version is updated with a few corrections and additions

A Source for Rav Kook’s Orot Hateshuva Chapters 1 – 3

A Source for Rav Kook’s Orot Hateshuva

Chapters 1 – 3

Chaim Katz, Montreal

first chapter of his Orot Hateshuva [1] as follows:

find three categories of repentance: 1) natural repentance 2) faithful repentance

3) intellectual repentance.

בשלש מערכות: א) תשובה טבעית, ב) תשובה אמונית, ג) תשובה שכלית

הטבע. שסוף כל הנהגה רעה הוא להביא מחלות ומכאובים . . . ואחרי הבירור שמתברר אצלו הדבר, שהוא בעצמו בהנהגתו הרעה אשם הוא בכל אותו דלדול החיים שבא לו, הרי הוא שם לב לתקן את המצב

natural physical repentance revolves around all sins against the laws of nature

ethics and Torah that are connected to the laws of nature. All misdeeds lead to

illness and pain . . . but after the clarification, when he clearly recognizes that

he alone through his own harmful behavior is responsible for the sickness he

feels, he turns his attention toward rectifying the problem.

Kook is describing a repentance that stems from a feeling of physical weakness

or illness. He also includes repentance of sins against natural ethics and

natural aspects of the Torah. A sin of ethics might be similar to the חסיד שוטה, who takes his devoutness to foolish

extremes (Sotah 20a). A sin in Torah might be one who fasts although he is

unable to handle fasting (Taanit 11b דלא מצי לצעורי נפשיה) [2].

collection of sermons Likutei Torah [3], also recognizes three types of

repentance. Homiletically, he finds the three types in Ps. 34, 15.

טוב, בקש שלום ורדפהו.

types

to three names of G-d that appear in the text of the berachos that we

say:

אתה ד’ אלוקינו

to R. Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the first level of repentance relates to the Divine

name Elokim (In Hassidic thought, repentance (teshuva or return) is

taken literally as ‘returning to G-d’, not only as repentance from sin.) The mystics

of the 16th century connected the name Elokim to nature.

[4]

is also related to ממלא כל עלמין, the immanence of G-d, which may have

something to do with the laws of nature.

follows:

באה האמונית, היא החיה בעולם

ממקור המסורת והדת

in the world from a source of tradition and religion.

of Liadi describes the second type of repentance as a return to the Divine

name Hashem, the Tetragrammaton. This

name signifies the transcendence of G-d, the name associated with the highest

degree of revelation, the name of G-d that was revealed at Sinai and that is

associated with the giving of the Torah.

level of repentance:

והחיים השלמה . . . היא מלאה כבר אור אין קץ

intellectual repentance . . . is a clear recognition that comes from an encompassing

world and life view. . . . It is a level filled with infinite light.

Torah study to the level of the Or En Sof, the infinite self-revelation

of G-d. It is a return to אתה

to Thou.

summary, R. Shneur Zalman discusses three types of teshuva, (although the

sources only speak about two types: תשובה מיראה , תשובה מאהבהYoma 86b). These three teshuva

categories form a progression. Rav Kook also speaks of a threefold progression:

a return based on nature, a return based on faith, and a return based on

intellect. [5]

by R. Shimon Glicenstein (published in 1973) [6]. R. Glicenstein was Rav Kook’s

personal secretary during the years of the First World War, when Rav Kook

served as a Rabbi in London.

the Rav’s room and I found him running back and forth like a young man. He was

holding Likutei Torah (the section on the Song of Songs) of the Alter

Rebbe (the Rav of Liadi) in his hand. With sublime ecstasy and great emotion, he

repeated a number of times: “Look, open Divine Inspiration springs out of each

and every line of these Hassidic essays and exegeses”.

ודרושי חסידות אלה מבצבץ רוח הקדש גלוי’

Repentance and Gradual Repentance. The chapter consists of three short

paragraphs: the first describes the sudden teshuva as a sort of spiritual flare

that spontaneously shines its light on the soul. The second paragraph explains gradual

teshuva is terms of a constant effort to plod forward and improve oneself without

the benefit of spiritual inspiration.

Torah [7]. R. Shneur Zalman of Liadi discusses

two levels of Divine service (not two levels of repentance). In one a spontaneous

spiritual arousal comes from above (itaruta de le-eyla) initiated by G-d as a

Divine kindness, without any preparation on man’s part. In the other (itaruta

de le-tata) man serves G-d with great exertion and effort, taming and refining his

own animal nature, without the benefit of any Divine encouragement.

Rav Kook begins by describing again the sudden repentance:

good of the G-dly good, which permeates all worlds.

track.

הלא הוא בא מהתאמתנו אל הכל, ואיך אפשר להיות קרוע מן הכל,

פרור משונה, מופרד כאבק דק שכלא חשב.

ומתוך הכרה זו, שהיא הכרה אלהית באמת,

באה תשובה מאהבה בחיי הפרט

ובחיי הכלל

from our symmetry with the whole. How can we be torn from the whole, like an

odd crumb, like insignificant specs of dust?

recognition, comes repentance from love in both the life of the individual and

the life of the society.

something in Likutei Torah. R. Shneur Zalman of Liadi (in the sermon just mentioned)

relates that people complain to him because they feel a spirit of holiness that

arouses them to emotional prayer for a only a short duration of time (sometimes

for a few weeks). Afterwards the inspiration ceases completely and it’s as if

it never existed. He responds, that they should take advantage of those periods

of inspiration when they occur, not just to enjoy the pleasure of prayer, but

also to change their behavior and character for the better. The state of inspiration

will then return.

think Rav Kook, in his own way is dealing with the same issue. Obviously, the

goal is the sudden, inspired teshuvah, but how do we get there? How do we take

the exalted periods of awareness and inspiration and regulate them, so that

they are more deliberate, intentional and continuous. I can’t say I understand

the answer, but I think Rav Kook is saying that if we recognize that we are

part of the “whole” and not separate then we will get there.

chapter, Rav Kook, distinguishes between a detailed teshuva relating to

specific individual sins and a broad general teshuva related to no sin in particular.

He writes (in the second paragraph):

סתמית כללית. אין חטא או חטאים של עבר עולים על לבו, אבל ככלל הוא מרגיש בקרבו שהוא

מדוכא מאד, שהוא מלא עון, שאין אור ד’ מאיר עליו, אין רוח נדיבה בקרבו, לבו אטום

is not conscious of any past sin or sins, but overall he feels crushed. He

feels that he’s full of sin. The G-dly light doesn’t enlighten him, he is not

awake; his heart is shut tight.

teshuva that is independent of sin is also found in Likutei Torah:

במי שיש בידו עבירות ח”ו אלא אפילו בכל אדם, כי תשובה הוא להשיב את נפשו שירדה מטה מטה ונתלבשה בדברים גשמיים אל מקורה ושרשה

only for those who have sinned (may it not happen), but it’s for everyone.

Teshuva is the return of the soul to its source and root, because the soul has

descended terribly low, and focuses itself on materialistic goals. [8]

the same symptoms as Rav Kook.

עמנו פנים אל פנים בלי שום מסך מבדיל . . .

מחיצה של ברזל מפסקת ונק’ חולת אהבה שנחלשו חושי אהבה ואומר על מר מתוק

the temple stood, when the Holy One blessed is He was with us face to face

without any concealment . . . However now in exile there’s an iron partition

that separates us. We are lovesick, meaning our love is weak. We don’t

distinguish bitter from sweet.

מטומטמת אין המח שליט עלי’ כ”כ

עבירה מטמטמת לבו שלאדם ונקרא לב האבן

in exile because the heart is shut down, the mind hardly can arouse it. Sin has

shut down the heart and it’s called a heart of stone. [9]

organization of the first three chapters of Orot Hateshuva, presents another

sort of problem: How are the types of teshuva in the three chapters related? Is

the intellectual teshuva of chapter one different from the sudden teshuva of

chapter two and different from the general teshuva of chapter three?

the arrangement of the three chapters follows the categories

of עולם שנה ונפש,

(which are found in Sefer Yetzirah). The first chapter examines natural return,

faithful and intellectual return. These are connected to נפש – one’s personality and understanding. The

second chapter deals with repentance and its relationship to time (שנה). Repentance

is either sudden or gradual. The third chapter speaks about a

return motivated by a specific sin or motivated by a general malaise. This can

possibly be associated with space/location (עולם); the world (or the specific sin) is

located somewhere outside of the person and motivates the person to return. Explanations based on the three dimensions of עולם שנה ונפש occur in a number of places in Likutei

Torah. [10]

I saw these two examples in Rav Kook’s Ein AY”H, (here).

the following paragraph, Rav Kook speaks about a natural spiritual, repentance

––pangs of remorse (if the sinner is an otherwise upright individual) that

motivate the sinner to perform teshuva.

(shorter) versions of the sermon published in other collections. (here)

Quoted also in the second part of Tanya, (Shaar Hayichud Vhaemunah)

beginning of chapter 6. The statement is usually attributed to R. Moshe

Cordovero, (Pardes Rimonim)

relied on an earlier source that I’m unaware of. Maybe R. Kook and R. Shneur Zalman arrived at a similar

understanding independently.

it looks like R. Glicenstein had given R. Tzvi Yehudah his essays and notes so

that they could be published. (here)

66c and Balak page 75b.

page 64d. Obviously, I don’t think that Rav Kook’s use of olam, shana, nefesh, (if

he’s in fact using that breakdown) comes specifically from Likutei Torah.

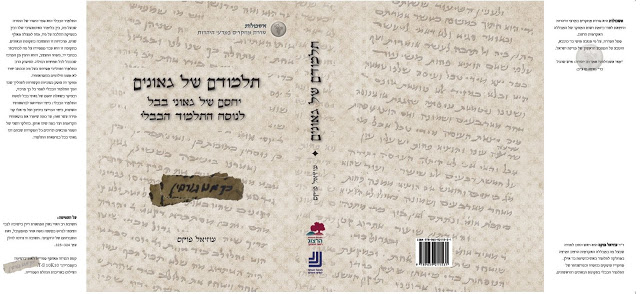

The Babylonian Geonim’s Attitude to the Talmudic Text

Talmudic text

we mentioned here

that the Seventeenth World Congress

of Jewish Studies took

place at the Mount Scopus Campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Over the next few months we will be

posting written transcriptions of some of the various presentations

(we hope to receive additional ones).

Babylonian Geonim’s attitude to the Talmudic text, the subject of his recently

released excellent book. To purchase

this work contact me at Eliezerbrodt-at-gmail.com. Part of

the proceeds will be used to support the efforts of the Seforim Blog.

תשע”ז

יחסם של גאוני בבל לעניינים טקסטואליים במשנה ובתלמוד הבבלי היא שאלה רחבה

ומורכבת, מכיוון שמדובר על תקופה של למעלה משלוש מאות שנה, שפעלו בה חכמים שונים

בכמה מרכזים.

בכמה נתונים מספריים שיאפשרו לנו למקד את הדיון.

השתמרו בערך 260 התייחסויות של הגאונים לעניינים טקסטואליים במשנה ובתלמוד. חלקם

ארוכים ומפורטים וחלקם כוללים הערה קצרה; מהם שהגיעו בשלימות ומהם מקוטעים וקשים

לפיענוח; הרבה מהם נכתבו כמענה לשאלות טקסטואליות אך לא מעט נכתבו ביוזמתם של

הגאונים עצמם.

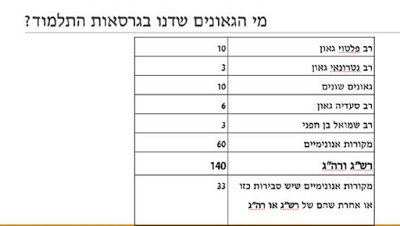

אחת הממצאים חד משמעיים – המקום המרכזי של רש”ג ורה”ג בתחום הטקסטואלי.

של המקורות שבהם רב שרירא גאון ורב האיי גאון עסקו בעניינים טקסטואליים אנו למדים

על המניעים שלהם לעסוק בגרסאות התלמוד. הרבה מהם נכתבו כתשובות לשואלים, בין

בעניינים טקסטואליים ובין בתשובות הלכתיות ופרשניות. באופן מיוחד מעניינות אותן

התשובות שבהן העניין הטקסטואלי הוא שולי, ואין הוא חיוני כלל ועיקר כדי לענות

לשאלה שנשאלו הגאונים, ואף על פי כן טרחו הגאונים להוסיף הערה ארוכה או קצרה

בעניין גרסאות התלמוד.

מיוחדת יש לכמה עשרות דיונים טקסטואליים שנכתבו בחיבורי הגאונים ולא בתשובותיהם.

מעניין פירושי רב האי גאון למסכתות ברכות ושבת, שבשרידים הלא רבים שהגיעו אלינו יש

עשרים וארבעה דיונים טקסטואליים. חלקם ארוכים, מורכבים ומפורטים. דיונים אלה

מלמדים אותנו שבעיני גאוני בבל האחרונים – רש”ג ובעיקר רה”ג – העיסוק

בגרסאות התלמוד הפך להיות חלק בלתי נפרד מסדר יומו של לומד ומפרש התלמוד.

מקום, העיסוק הטקסטואלי האינטנסיבי המרובה של שני גאוני פומבדיתא המאוחרים – רב

שרירא ורב האי רב שרירא – מלמד שאת כותרת ההרצאה ‘יחסם של גאוני בבל לטקסט

התלמודי’ יש לסייג הרבה. על שאר הגאונים אנחנו יודעים מעט מאוד, ועל יחסם של רוב

רובם של גאוני בבל לעניינים טקסטואליים אי אפשר לומר מאומה.

להאריך במחשבות ובהשערות בעניין זה – מה המשמעות של מיעוט הדיונים הטקסטואליים של

רוב הגאונים: האם מדובר על עניין מקרי – הדיונים שלהם לא הגיעו לידינו, או שמא

באמת עסקו פחות בעניינים טקסטואליים. אך בשל קוצר הזמן לא אכנס לכך.

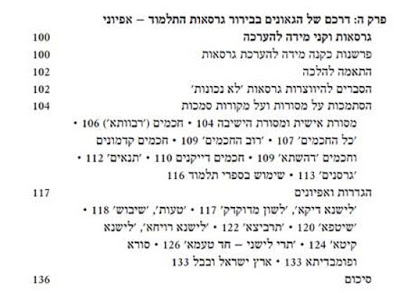

בולט של אחרוני הגאונים הוא יצירת הגדרות או שימוש ב’כלי עבודה’ כדי לדון בגרסאות

השונות. לא רק קביעות בסגנון של ‘גרסה נכונה’ או ‘גרסה לא נכונה’ אלא ניסיון ליצור

קני מידה על מנת לשקול בין הגרסאות השונות, ולהכריע איזו מהן נכונה יותר. כמו כן,

הגאונים המאוחרים תייגו גרסאות שונות באיפיונים: מדוייק, לא מדוייק.

אלה חשובים עד מאוד, והם מלמדים הרבה על החשיבה הביקורתית של אחרוני הגאונים, על

השימוש שלהם בכלים שהיינו מכנים ‘מחקריים’ או ‘ביקורתיים’. אף על פי כן, יש להדגיש

כי קני המידה והאפיונים השונים באים בראש ובראשונה בשירות הפרשנות.

את הקביעה הזו בשתי דוגמאות הבאות בדברי הגאונים רב שרירא ורב האיי.

השאיפות של חקר מסורות בכלל וחקר גרסאות התלמוד בפרט היא מציאת המסורות והגרסאות

המדויקות והמהימנות. ואכן, אחרוני הגאונים קבעו לגבי לא מעט גרסאות שהן מדויקות,

או שהן של חכמים דייקנים.

יש לברר – מה הופך חכמים אלה להיות חכמים דייקנים בעיניהם של אחרוני הגאונים? האם

המסורות שעליהם הסתמכו או שמא דרך כזו או אחרת שבה הצליחו לשמר את גרסאות התלמוד?

ושמא היה להם קריטריון אחר?

תשובות אנו מוצאים רמז לעניין, ושתיהן נוגעות לסוגיה הטעונה של הפער שבין נוסחי

הפסוקים שבמקראות לבין נוסחם בגרסאות התלמוד.

כתב רב האיי גאון:

אילו היה הפסוק כטעותם… אלא שאינו כן, דרבנן דווקני ומי שמעיינין בשמועה

ואינן גורסין והולכין שיטפא בעלמא…’.

זו כרך רה”ג כרך את הדיוק של אותם ‘רבנן דווקני’ ב’מי שמעיינין בשמועה’,

כלומר, הם אינם גרסנים מכניים, אלא הם מבינים את המתרחש בסוגיה. ה’דיוק’ של המסורת

קשור ל’עיון בסוגיה’, להבנתה ולהתאמתה למסורת ה’נכונה’ במרכאות, כלומר זו שאינה

יוצרת קשיים פרשניים. ה’דיוק’ מוגדר ככזה בזמן שהוא משרת את הפרשנות הנכונה.

לעניין החכמים הדייקנים עוד מעט. ונעבור לפני כן לקנה מידה אחר לבחינת גרסאות

התלמוד.

תשובות הגאונים – שוב רב שרירא ורב האיי גאון – קבעו שגרסה מסוימת היא גרסת ‘כל

החכמים’. הקביעה הזו, המסתמכת על ‘כל החכמים’ היא בוודאי שיקול נכבד בעד גרסה

מסוימת. רה”ג השתמש בקביעה הזו גם בתשובתו הידועה בעניין מנהגי תקיעת שופר

בראש השנה: ‘והלכה הולכת ופשוטה היא בכל ישראל… ודברי הרבים הוא המוכיח

על כל משנה ועל כל גמרא, ויותר מכל ראיה מזה פוק חזי מה עמא דבר, זה העיקר והסמך’.

התפיסה הזו, או כפי שכונתה בערבית ‘אג’מאע’ היא גם אחד מארבעת היסודות של פסיקה

ההלכה המוסלמית. כאמור, קביעות כעין אלה באו כשיקול טקסטואלי בדברי הגאונים. ברוב

הפעמים הקביעה שגרסה היא ‘גרסת כל החכמים’ באה להכריע כמו גרסת הגאונים בתלמוד

הבבלי בניגוד למקור אחר – גרסה בתוספתא, גרסת ספרי משנה וגרסה הבאה בהלכות פסוקות

והלכות גדולות.

בתשובה בעניין נוסח פסוק בספר דברי הימים, המובא בגרסה שונה בסוגיה בתחילת מסכת

ברכות, קבעו רב שרירא ורב האיי גאון באופן נחרץ: ‘וחס ושלום דהאוי שיבוש בקראיי,

דכולהון ישראל קריין להון פה אחד והאכין גארסין רבנן כולהון בלא שיבושא

ובלא פלוגתא ובלא חילופא‘.

של אותה תשובה הוא גם הזהיר לתקן גרסה זו, וגם כאן הזהיר את כל החכמים – ‘ואזהר

לתיקוני לנוסחי… ולאיומי על כולהו רבנן ותלמידי למגרס הכי דלא תהוי חס

ושלום תקלה במילתא’. קביעות נחרצות אלה הן מאוד חד משמעיות – יש גרסה אחת ויחידה

בתלמוד שהיא גרסת כל החכמים, והיא מתאימה לנוסח הפסוק בדברי ימים. אלא שהמציאות

אינה כל כך חד משמעית, ובמהלכה של אותה תשובה ציין רב האיי גאון לנוסח נוסף בסוגיה

– וכאן אנחנו חוזרים גם להגדרת ‘דוקאני’ שעליה עמדנו לעיל:

הוא אומ'[ר] באֿבֿיֿוֿ בלישנֿאֿ רויחאֿ, ומאןֿ [ד]גֿאריס לישאנא קיטא

ולא דאייק למיגרס וכן הוא אומר באביו הכין מפריש דגאמרֿין מן אבא לברא אבל קרא

כולי עלמא פה אחד קארו ליה וגרסין ליה וכיון דהכין היא שמעתא איסתלק ליה

<ספיקא>’. כלומר, על אף שבעיקרו של דבר הגאונים לא נסוגו מן הקביעה שכל

החכמים גורסים את הפסוק בסוגיה כמו נוסחו בספר דברי הימים – כלומר ‘יהוידע בן

בניהו’, הרי שהוא מוסיף שיש הגורסים גרסה מרווחת יותר, שבה נוספה לשון פירוש ‘וכן

הוא אומר באביו’ המבהירה שהפסוק בעניין ‘יהוידע בן בניהו’ מתייחסת לאביו של ‘בניהו

בן יהוידע’ המוזכר בהקשר אחר בסוגיה.

אומרת, שהקביעה שגרסת הסוגיה היא גרסת ‘כל החכמים’ אינה קביעה מוחלטת. היא מתייחסת

לנושא המרכזי בעיני הגאון – נוסח הפסוקים המצוטט בסוגיה – אך בעניין אחר הוא מבהיר

שיש גרסה יותר מדויקת של ‘רבנן דוקאני’ הגורסים ‘לישנא רויחא’ ובה הסבר נוסף

המסביר באופן מוצלח יותר את הסוגיה, ומדגישה ‘וכן הוא אומר באביו’, וכך אפשר להבין

את רצף הפסוקים המלמדים על בניהו בן יהוידע מפסוק העוסק ב’יהוידע בן בניהו’.

למדים ששלושת הקריטריונים – אזכור ‘רבנן דוקאני’, הקביעה שגרסה היא גרסת כלל

החכמים, וההבחנה בין ‘לישנא קיטא’ ל’לישנא רויחא’ – מובאים על מנת לפרש את הסוגיה,

ולצנן את ‘תפוח האדמה הלוהט’ שעליו העמידו השואלים. הדיון איננו דיון טקסטואלי

טהור, אלא דיון טקסטואלי שנועד לפתור בעיה פרשנית – במקרה זה אי ההתאמה בין

המקורות.

זו מצטרפת לעובדה שגם במקומות אחרים קנה המידה המרכזי של גאוני בבל לדיון בגרסאות

התלמוד הוא ההתאמה לפרשנות ולעניין.

מעט מופרזת אפשר לקבוע שדרכם של אחרוני הגאונים הפוכה מסדר הפעולות הפילולוגי

שעליו המליץ פרופ’ אליעזר שמשון רוזנטל המנוח. בעוד שהוא קבע ש’על שלושה דברים כל

פרשנות פילולוגית-היסטורית עומדת: ‘על הנוסח, על הלשון, על הקונטקסט הספרותי

וההיסטורי-ריאלי כאחד… ובסדר הזה דווקא’, הרי שרב שרירא ורב האיי העדיפו דווקא

את הפרשנות, את העניין, ואת הקונטקסט הספרותי על פני הגרסה והנוסח.

של קביעה זו נשוב לקראת סוף הדברים.

נובע העיסוק המרובה של גאוני בבל בגרסאות התלמוד? מה גרם לגאוני בסוף המאה העשירית

ותחילת המאה האחרת עשרה להקדיש מאמץ לימודי ליצירת הגדרות וקני מידה לדיון בגרסאות

הללו?

הסביר, שכבר הובא בספרות המחקר, הוא ריבוי הגרסאות בסוף התקופה. סביר להניח

שהגרסאות הללו באו מתוך שתי ישיבות הגאונים, אולי מחוגים אחרים בבבל, ואולי אף

גרסאות שהגיעו אליהם מן התפוצות.

לא פעם הדיון של הגאונים מתייחס במפורש לגרסאות של חכמי התפוצת שפנו אליהם

בשאלותיהם.

כאן דוגמה אחת לדיון ייחודי של אחד הגאונים בתגובה לגרסה שהגיעה אליו מן התפוצות,

או ליתר דיוק לתגובה של הגאון להצעה להגיה גרסה של סוגיה ביבמות.

להקשות ואמרתה אלא סופה דקאתני עמד אחד מן האחין וקדשה אין לה עליו כלום היכי

מתריץ לה רב אשי עמד אחד בין מן הילודין בין מן הנולדין וקדשה אין לה עליו כלום

והלא ר’ שמ'[עון] לא היה חלוק אלא בנולדין בלבד אבל הילודין לא היה צריך להזכיר

אותם בכלל, ואמרת כי עלה על לבבך לשנות עמד אחד מן הילודין שכבר נולדו

וקידשה אין לה עליו כלום ולעקור מן האמצע… אבל אמרת כי לא מלאך לבך לסמוך על

דעתך […] שקיימתה […] הספרים

אשר בֿמק[ו]מ[כם כ]אשר אמרת […]מתחילה ועד סוף, כי זה שאתם שנים כתוב גם

עדיכם עמד אחיו בין מן הילודין וֿבין מן ה[נו]לדים […] אין לה עליו כלום, כך

אנו שונין…

הצעות הגהה של אחרוני הגאונים שמענו, ולרה”ג יש מעט הצעות להגיה גרסאות של

התלמוד, אך זו הדוגמה היחידה הידועה לי שבה השואלים הציעו בפני הגאון להגיה

את סוגיית התלמוד.

יחידה זו מצטרפת לשאלות של חכמי התפוצות מן הגאונים. בעוד שהרבה מן השאלות

בעניינים טקסטואליים הן שאלות מאוד פשוטות, חלק מן השאלות לאחרוני הגאונים הן

שאלות מורכבות ובהם קושיות מפורטות על גרסאות התלמוד, והן כוללות השוואה בין

מקורות שונים. שאלות אלה נשאלו על ידי גדולי החכמים בתפוצות: ר’ משולם בר’

קלונימוס, רב יעקב מקיירואן, ור’ שמריה בר’ אלחנן במצרים.

שריבוי הגרסאות בישיבות, והאתגר שהשואלים, חכמי התפוצות, הציבו לגאוני בבל – חידדו

את הצורך שלהם להתמודד עם הגרסאות השונות, להפוך אותם לחלק מסדר היום הלימודי

שלהם, וליצור קני מידה לדיון והכרעה בין גרסאות וכן אפיונים שבהם כינו את הגרסאות

השונות. אפשרות זו היא השערה סבירה, אך היא נותרת בגדר השערה.

הגרסאות לא היה רק מניע משוער לפעילותם של הגאונים בעניינים טקסטואליים. הוא הפך

להיות חלק מן הדיון עצמו. אבהיר את הדברים – אך אאלץ לומר בעניין דבר והיפוכו.

כלומר הגאונים כתבו דברים בגנות ריבוי הגרסאות, אבל הם גם השתמשו באותו ריבוי

גרסאות – גם לעניינים פרשניים והלכתיים.

ביאור הדברים.

מקורות, אחרוני הגאונים טענו שגרסה מסוימת היא ‘שיבוש’ אך ברור שאין הכוונה לכך

שהגרסה מוטעית או לא נכונה, אלא לכך שיש לסוגיה כמה גרסאות.

ביותר באה בתשובה של רב האיי גאון, שבה התבקש לפרש בהרחבה סוגיה במסכת סוטה:

דתנו רבנן… לרוח לן גאון בפירושיה

ולא זה מקום הספק אלא הספק בשינוי לשונות דאמ'[ר] רב

משרשיא איכא ביניהו עראבא ועראבא דעראבא. ושינוי לשונות דגראסי הוא שבוש וכולן

טעם אחד הן. יש שונין כך…….

שגורסין…

רב האיי ברור שאין מדובר על שיבוש במובן של טעות שהרי ‘כולן טעם אחד הן’ ומכיוון

שבהמשך דבריו הוא מבאר את שתי הגרסאות – אלא שעצם העובדה שיש ‘שינוי לשונות

דגראסי’ הוא הוא השיבוש. בדומה לכך, יש עוד כמה מקורות שכאלה, ומהם אנו למדים על

אי הנחת של אחרונים הגאונים מריבוי הגרסאות.

שני, יש מקומות שבהם הגאונים ציינו כמה גרסאות ונראה שהדבר לא נראה מוזר או קשה

בעיניהם. במקומות שבהם מדובר על עניין פרשני או לשוני גרידא אין בכך כל תמיהה. אך

הגאונים אך השתמשו לעתים בגרסאות כאילו הן דעה הלכתית לגיטימית.

הבולטת ביותר היא תשובה אנונימית, <מצגת< שבה השואלים והגאון המשיב

ציינו שיש לסוגיה שתי גרסאות, וכיוון שאי אפשר להכריע מתייחסים לכך כאל ‘תיקו’

תלמודי:

גאון, דאיכא נו<סח>י דכתיב בהו מבני חרי ואיכא דכתיב בהו ממשעבדי.

חייכון אחינו שגם אצלינו כך הוא, איכא דגרסי מבני חרי ואיכא דגרסי ממשעבדי. מיהו

רובא דרבנן דעליהון סמכא דגרסי מפום רבוותא דעליהון סמכא דשמעתא גרסי ומגבי ביה

ממשעבדי,

ואעפ”כ <כיון> דאיפליגו בהא גרסאי דהוו מעיקרא, ליכא כח בהא

מילת'[א] <למיזל> בתר רובה ולקולא עבדינן ולא מגבינן ביה ממשעבדי.

שלגאון הייתה גרסה שהוא העדיף אותה – זו של רובא דרבנן – ואף על פי כן התייחס

לגרסה השנייה כאל אופציה ממשית, המשפיעה על פסיקת ההלכה בסוגיה.

דוגמה נוספת בתחום שאינו הלכתי. כאשר רש”ג ביקש באיגרתו להבהיר שגם בתקופת

קדומות היה ‘תלמוד’ הוא הגדיר:

הוא חכמה דראשונים, וסברין <ביה> טעמי משנה דתנו רבנן

רבו לא רבו שלימדו משנה ולא רבו <שלימדו> מקרא אלא רבו שלימדו תלמוד.

ואיכא דתאני שלימדו חכמה ותרויהו חד טעמא אינון דברי ר’ מאיר, ר’ יהודה אומר

כל שרוב חכמתו ממנו…

שגרסתו בתלמוד היתה ‘רבו שלימדו תלמוד’ אך רב שרירא ‘ניצל’ את הגרסה האחרת, והשתמש

בגרסה ‘רבו שלימדו חכמה’ כדי ללמדנו ששתי הגרסאות מקבילות, ושאין ‘תלמוד’ אלא

חכמה, חכמת הראשונים.

למדים – כפי שכבר אמרתי לעיל – שביחס לריבוי הגרסאות אנו מוצאים שימוש בשתי גישות

הפוכות. רצון למצוא גרסה אחת ויחידה, ואי נחת מריבוי הגרסאות והגדרתן כ’שיבוש’

מזה, אך גם הצגת כמה גרסאות, ואף שימוש פרשני והלכתי בגרסאות האלטרנטיביות מזה.

זו לא ללמד על עצמה יצאה. גם בנקודות

אחרות אפשר להראות שהגאונים השתמשו בגישה טקסטואלית אחת, אך גם בגישה ההפוכה. כך

למשל בנוגע להגהת התלמוד.

האיי גאון קבע במילים נרגשות:

ששמועה זו למשמע אוזן נוח מן הראשון אלא שלא כך גרסתנו ולא כך גרסו הראשונים, ואין

לנו לתקן את המשניות ואת התלמוד בעבור קושיא שקשה לנו.

במקום אחר הציע לשנות את גרסת הסוגיה בשל קושי פרשני:

עייננא בהדין [גירסא] ולא סליק ליה פירושא אליבא דפש[אטא דהי]לכתא.

אימת דאתית לשוויה להא מותיבי להאי שמעתא לר’ יוחנן ולמימר הוא מפריק לא קא

סלקא שמעתא לדילנא כל עיקר.

משוית ליה לקושיא ולפירוקא לרב הונא סליקא ליה שמעתא ולא קאיים בה מידעם.

חזינא דמבעי למגרס: בשלמא ללישנא קמא רב הונא כר’ מאיר ור’

יוחנן כר’ יהודה.

שאותו חכם אומר דבר והיפוכו באותו עניין ובהקשרים שונים אינה מפתיעה כל מי שמצוי

בספרות הרבנית, אך היא מבלבלת את החוקר שמנסה לעשות סדר, ולהטיל שיטה בדברי

הקדמונים.

דבר. בהרצאה זו ביקשתי לטעון שלוש טענות. ביקשתי לטעון שבסוף תקופת הגאונים הפך

הדיון בגרסות התלמוד להיות חלק אינטגרלי מאופן הלימוד והכתיבה של הגאונים – הם

עסקו בגרסאות התלמוד פעמים רבות, הן כאשר השיבו לשואליהם הן בשעה שכתבו את

פירושיהם. לא זו בלבד – וזו הנקודה השנייה – הם אף יצרו כללים והבחנות חשובות

הנוגעות להיבטים הטקסטואליים של ספרות חז”ל.

על פי כן – וזו הטענה השלישית – ביקשתי לטעון שבמידה רבה כלים פילולוגיים אלה היו

משועבדים בראש ובראשונה לפרשנות התלמוד. כיוון שכך הם היו עשויים להתמקד בפרשנות

סוגיה מסוימת או בפסיקת הלכה בעניין מסוים, תוך שימוש בכלים טקסטואליים שונים או

הפוכים מאלה שהם קבעו בהקשרים אחרים.

הפעמים שבהם גאוני בבל עסקו בטקסט התלמודי – לעתים תוך רגישות טקסטואלית והבנה

יוצאת מן הכלל של דרכי המסירה ותהליכי שיבוש ושינוי בטקסטים הנמסרים בעל פה או

בכתב – אינה הופכת את פעולתם לשיטה או למדע במובן המודרני, וכאמור, הבנה זו מאפשרת

לנו להבין סתירות בדרך שימושם של הגאונים בקני המידה שקבעו.

לחזור לכותרת ההרצאה: ‘יחסם של גאוני בבל לגרסאות התלמוד’ – הרי שיחס זה היה

משועבד בראש ובראשונה לשימור המסורת שלהם, לפרשנות של סוגיות התלמוד ולפסיקת הלכה,

ולא כל כך לקביעת כללים ועקרונות מוצקים.

מקווה שלא אפגע בפרופ’ רמי ריינר שנתן למושב את הכותרת היפה שלו – ‘ראשונים

כחוקרים’ – אם אטען שהראשונים – לפחות בתחום שבו עסקתי – לא היו באמת חוקרים. הם ידעו שיש בתלמוד

גרסאות קצרות ולשונות פירוש, הם ידעו לקבוע שגרסה השתבשה כתוצאה מגיליון שחדר

לפנים הטקסט, הם הבינו כיצד גרסאות השתבשו כתוצאה מן ההגייה השגויה של מילים. אך

הם היו בראש ובראשונה לומדי תורה, מפרשי תלמוד ופוסקי הלכה.