China and the Answer to the Last Quiz

Marc B. Shapiro

I recently returned from China and one of my friends asked me if during my time there I found anything of relevance to the Seforim Blog. He did not mean the comment seriously, but in fact I did find something. Whenever I am in synagogues I make a point of examining their collection of books, as you never know what you might come across. In Beijing I was at the fabulous Chabad House and I found something that will be of interest to Seforim Blog readers. Before getting to that I need to mention that my time in Beijing was made doubly special as I was able to spend Shabbat with Rabbi Dr. Dror Fixler. In addition to being an outstanding award-winning scientist, he is also a fine Judaic scholar. Among his important publications are new translations from the Arabic of Maimonides’ commentary on the Mishnah to tractates Berakhot, Peah, and Avodah Zarah. Each volume is accompanied by Fixler’s learned notes. Fixler has also published numerous articles on various Torah themes, including on practical halakhic matters. See here.

Fixler is a student of R. Nachum Eliezer Rabinovitch, and I used some of the time we were together to clarify the details of R. Rabinovitch’s position that there is no halakhic prohibition in using an electronic key card on Shabbat,[1] or in walking through a door that opens electronically, or even using an electronic faucet where the water comes out when you put your hand under it. Without getting into the halakhic details, I think one thing is sure, namely, that the future will bring more such lenient decisions in this area. The changing circumstances of modern life will create enormous pressure for lenient decisions, as modern technology which helps us in so many ways also creates many problems regarding Shabbat. For example, how long until it will be impossible to access an apartment building in New York and other big cities without using a key card? The day is probably coming when private apartment doors will also use key cards, not to mention numerous other such Shabbat-problematic technological advances that will be unavoidable aspects of life in the future. Therefore, I believe that some future poskim will return to R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach’s position that if there is no creation of heat or light, then technically there is no violation of Shabbat.

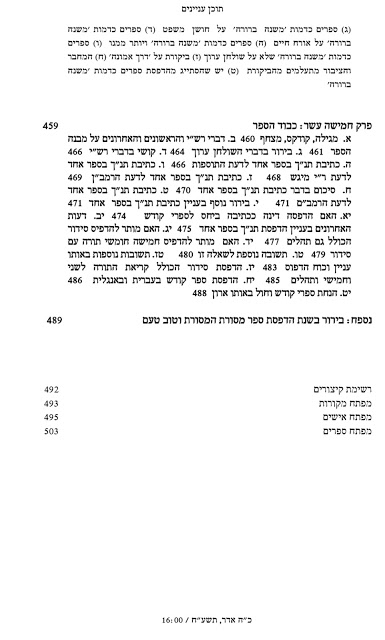

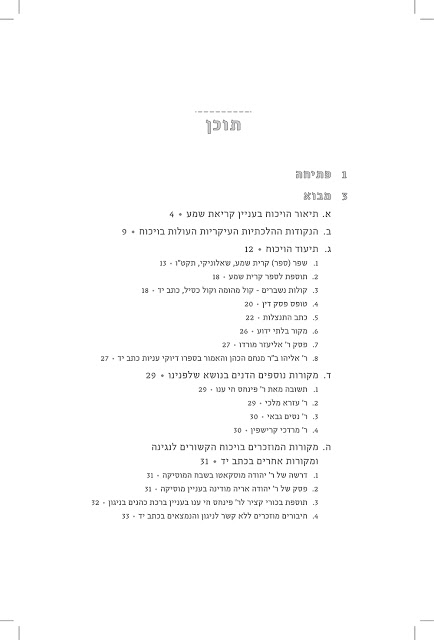

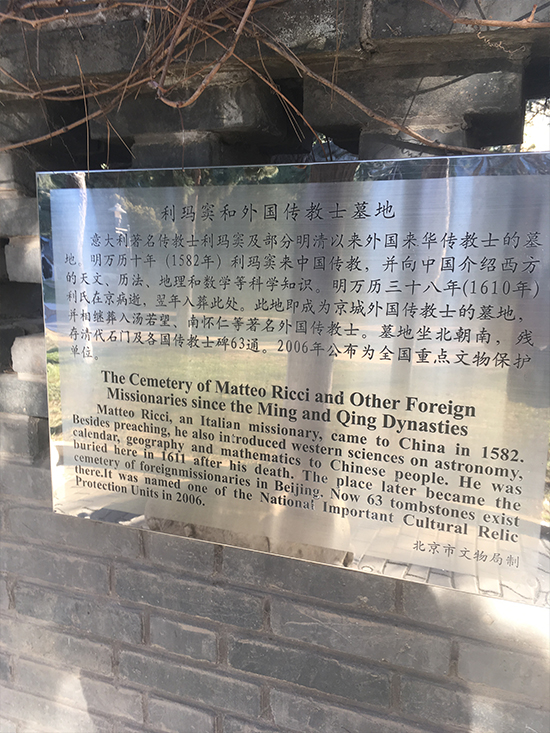

Getting back to the matter of seforim, while looking through the books at the Chabad House I saw Birkat Yadi by R. Joseph Judah Dana.

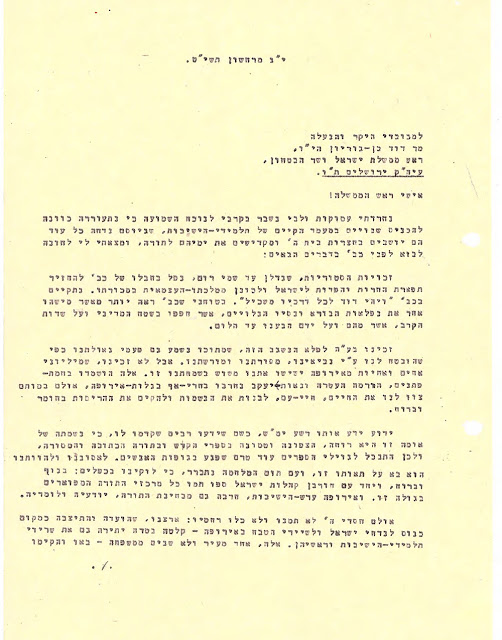

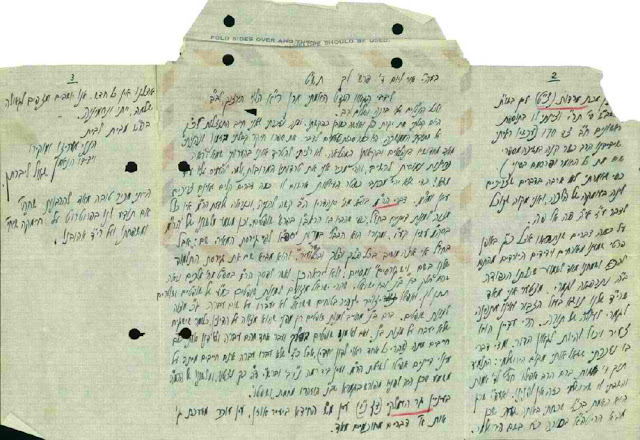

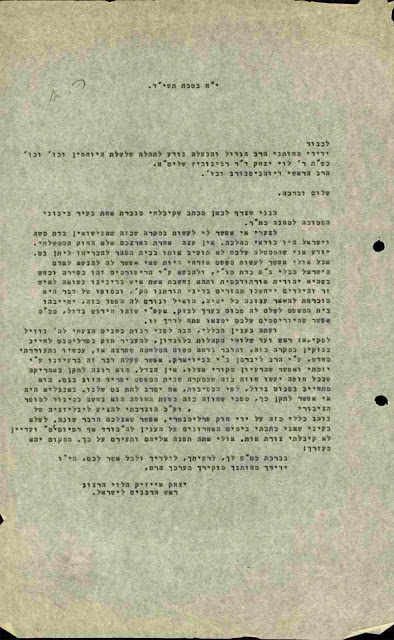

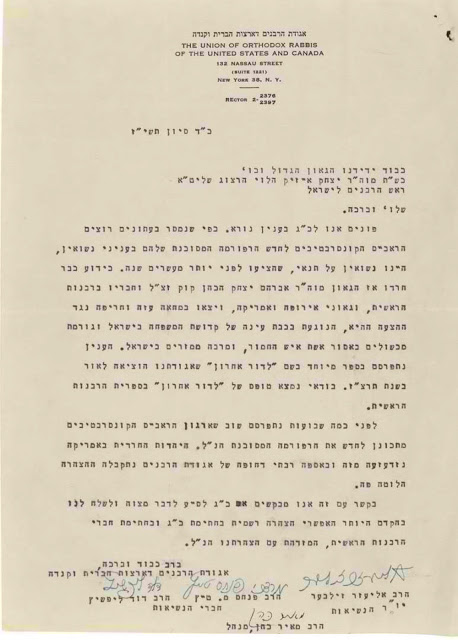

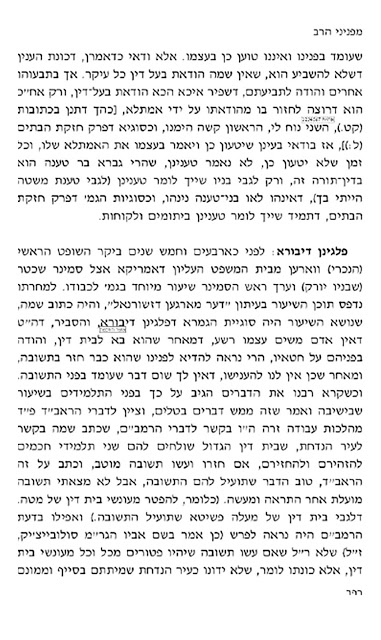

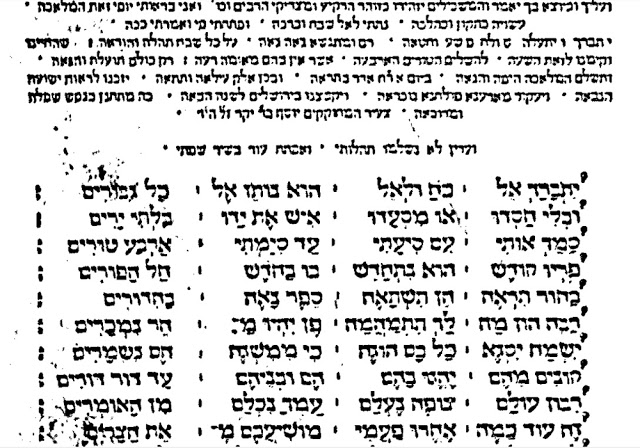

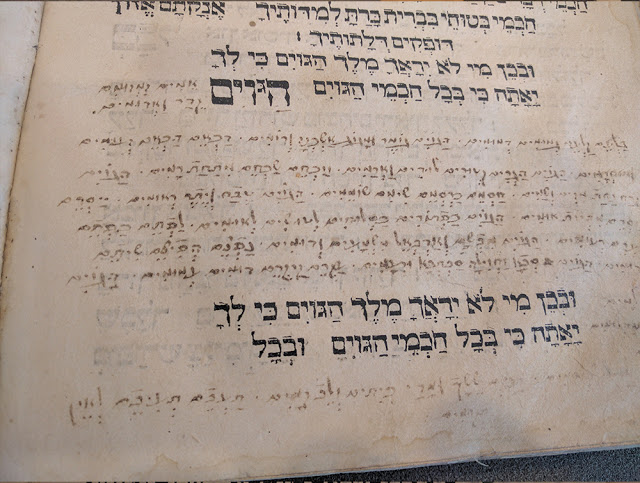

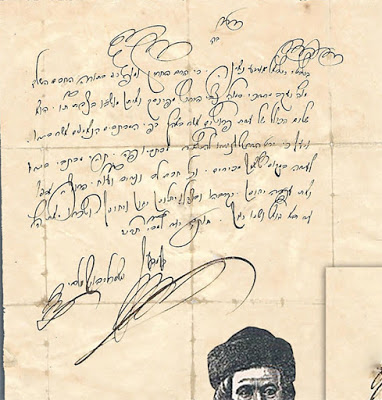

I had never before seen this book and it is not found on Otzar ha-Chochmah. Pasted on the inside cover is the following. (Unfortunately, the pictures I took came out blue on my phone.)

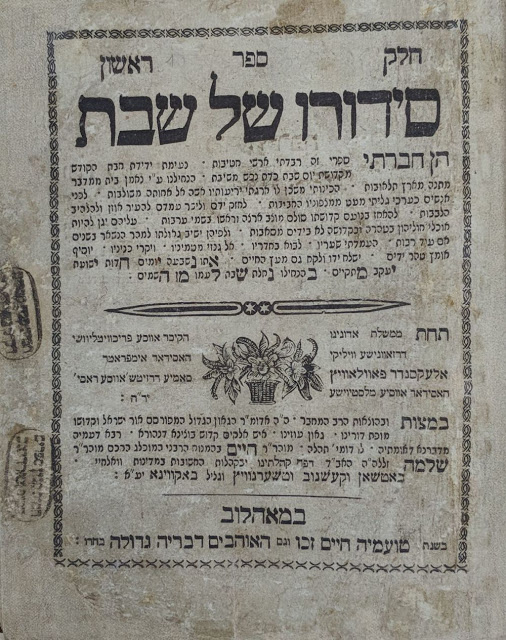

The book the editor, Prof. Joseph Dana, is referring to is Tzofeh Penei Damesek. Here is the title page.

Without getting into the accusation of plagiarism, there is something that is noteworthy about Tzofeh Penei Damesek, namely, that included among the approbations from great rabbis is a lengthy letter from Professor José Faur.

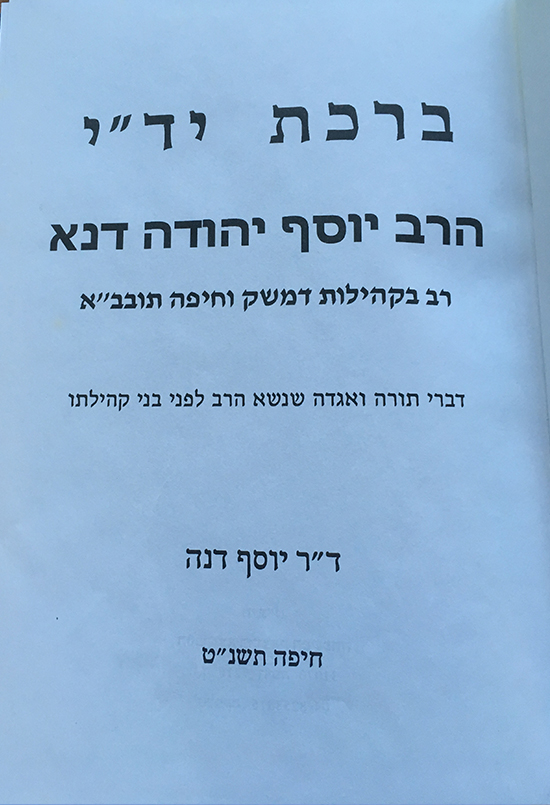

Let me share one other interesting thing about my recent trip to Beijing. It isn’t related to seforim but was of great interest to my colleagues at the University of Scranton, which is a Jesuit university. The Friday night before arriving in Beijing I was in Hong Kong and learned that one of the people I was talking to at dinner shared my interest in Matteo Ricci (1552-1610), the famous Jesuit missionary to China. This man told me that years before he had visited Ricci’s grave and that it was worthwhile for me go see it. There is actually a Jewish connection here, for Ricci was asked if he would take over the position of rabbi of the Kaifeng Jewish community, but on the condition that he give up eating pork.[2] (Obviously the Jews of Kaifeng were not the most learned.)

I checked online and saw that Ricci’s grave, which is found in the first Christian cemetery in China, was indeed a site that some tourists had written about. However, in recent years it had become much harder to visit without being part of an organized group and arranging the visit ahead of time. The fact that the small cemetery is found on the grounds of a Communist party school is no doubt the reason for this. I was thus unsure whether they would allow me in, but my guide was able to convince them that I was harmless. If it were only so easy to get into some of the old Jewish cemeteries I have attempted to visit.

Here is the grave and the plaque put up nearby.

Concerning China there is a lot more I have to say, and I hope to publish a manuscript from a few hundred years ago regarding the Jews of China. For now, let me just note the following which will be of particular interest to Seforim Blog readers: There are two works of responsa that were published by rabbis who served in China. (I am not including Hong Kong which I will return to in a future post.) The first is R. Elijah Hazan’s Yedei Eliyahu. Here is the title page of volume 1.

R. Hazan published three volumes in total. What makes his responsa very unusual, if not unique, is that the text is published complete with vowels. I don’t think I have ever seen another responsa collection published with vowels. Here is a sample page.

As R. Hazan explains in the introduction, he was the hazan in the Ohel Leah Synagogue in Hong Kong for fourteen years. Following this, for ten years he served as hazan at the Ohel Rachel Synagogue in Shanghai. Both of these synagogues still exist, but Ohel Rachel is now part of the Shanghai Educational Ministry and tourists are not permitted entry.

The second work of responsa by a rabbi in China is R. Aaron Moses Kiseleff’s Mishberei Yam. Here is the title page.

This book is significant not only because the author lived in China, but also because the book itself was printed in China in 1926, in the city of Harbin. Because of its proximity to Russia, Harbin attracted many Russian Jews and they were the ones who brought R. Kiseleff there. In the 1920s the Jewish population of Harbin was over 20,000.[3] As late as the 1940s there still was a Jewish day school in Harbin.[4]

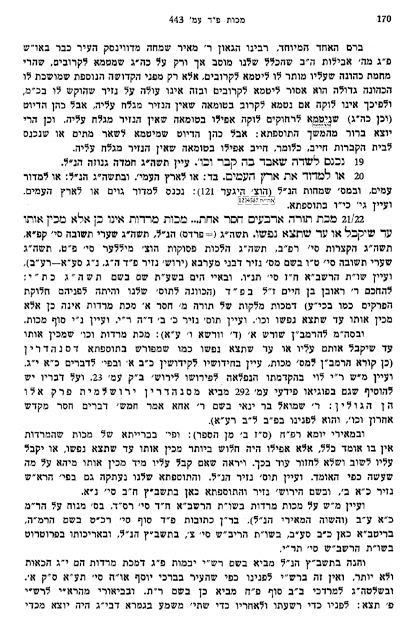

Not long ago I saw that R. Gedaliah Felder, Yesodei Yeshurun: Shabbat, vol. 2, p. 216, refers to R. Kiseleff’s Mishberei Yam, and in a footnote writes:[5]

הספר הזה חשוב מאד כי זה הספר היחידי של הלכה שנדפס ברוסיא אחרי המהפכה, נדפס בשנת תרפ”ו.

No doubt because he saw the Russian writing on the title page of Mishberei Yam, R. Felder mistakenly assumed that Harbin is in Russia. He thus concluded falsely that Mishberei Yam is the only book on halakhah published in the Soviet Union. While this is incorrect, had he known the truth he could have kept the footnote but changed it to say that Mishberei Yam is important since it is the only original book on halakhah published in China.

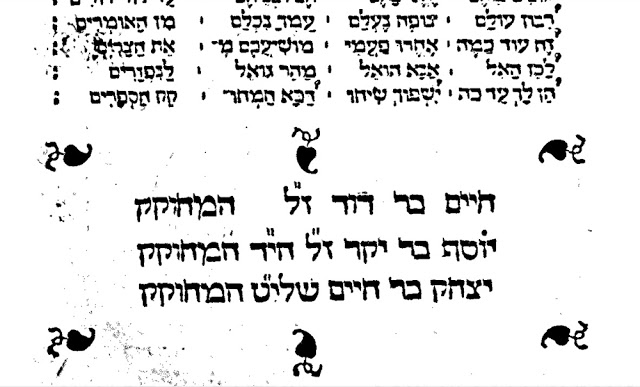

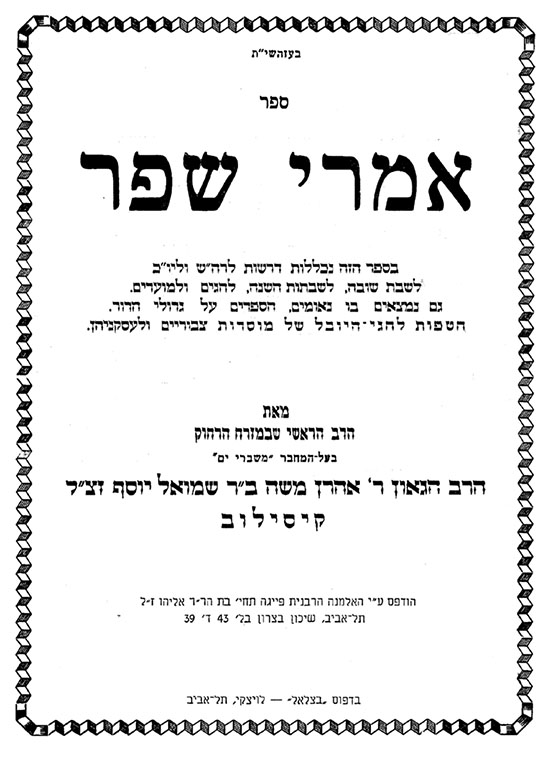

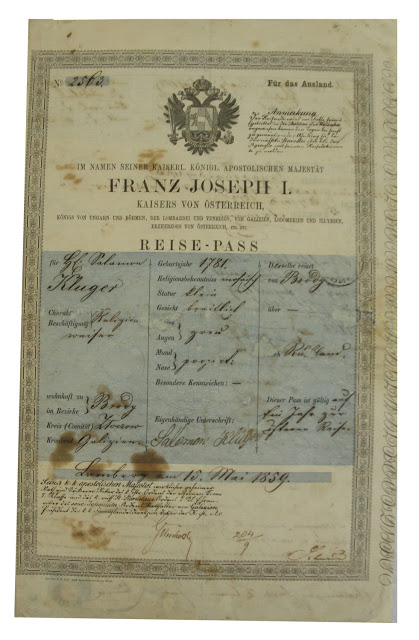

R. Kiseleff served as rabbi in Harbin from 1913 until his death in 1949. After his death, his widow moved to Israel and published R. Kiseleff’s derashot, Imrei Shefer. Here is the title page which refers to R. Kiseleff as the chief rabbi of the Far East.

As explained in the introduction, R. Kiseleff was actually given this title in 1937 at a gathering of Far East Jewish communities.[6]

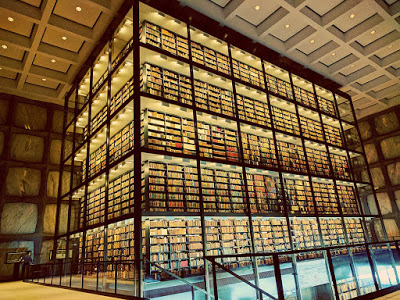

Herman Dicker writes as follows:[7]

Rabbi Kiseleff was a great Talmudic scholar who first came to Harbin when he was in his forties. He was born in Sores, Russia, in 1866 and as a child excelled in Jewish studies. He soon became known as the Vietker Ilui (wonder child), taking his name from the Yeshiva he attended as a youth. At sixteen, he transferred to the Yeshiva of Minsk, and, two years later, moved over to the Talmudic Center of Volozhin, where he studied with the famed Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik. . . . Rabbi Kiseleff was ordained by Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzenski and then served as the rabbi of Borisoff from 1900-1913. In his final year at Borisoff, in 1913, Rabbi Kiseleff was called to Harbin and he accepted the post as spiritual head there at the gentle urging of the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

Within a short period of time, Rabbi Kiseleff won the love and admiration of the entire community and achieved a great deal in raising the spiritual level of this remote Jewish congregation. It was, therefore, fitting that in 1937 he was elected, unanimously, as Chief Rabbi by the General Conference of the Far Eastern Jewish Communities. . . .

In 1931, he published Nationalism and Judaism, a Russian-language volume of sermons and lectures on the significance of Judaism. . . . Rabbi Kiseleff enjoyed the friendship of all the religious and intellectual leaders of Manchuria, without regard to their nationality or faith, for they all admired him as a person and respected his vast knowledge in various areas of academic learning. At one time, he debated the “Merchant of Venice” and the image of Shylock with three university professors and to this day scores of men and women remember his brilliance and eloquence on that occasion.

There is a good deal of interesting material in R. Kiseleff’s Mishberei Yam, and let me call attention to just a few things. In no. 15, R. Kiseleff rules that if there is a non-Jew who wants to convert but the doctors tell him that it is dangerous for him to be circumcised, he still cannot be converted without a circumcision. In this responsum, R. Kiseleff also writes about how rabbis should avoid converting people who are not serious about being good Jews (although he assumes, as most rabbis did until recent years, that a conversion with such people would still be valid ex post facto).

ובכלל עלינו להתרחק בכל האפשר לקבל גרים כאלו שידוע שרוב הגרים הבאים להתגייר בימינו לא משום אהבתם לדת ישראל באמת רק על הרוב סבות אחרות בדבר משום אשה או דומה לזה ואף שמלמדים אותם לומר בפני ב”ד שאוהבים את דת ישראל ומטעמים ידועים אין אנו דוחים אותם שהרי בדיעבד גם בכה”ג הוי גר, אבל גרים כאלו יותר נוח לנו שאם נמצא אמתלא שלא לקבלם מהראוי להתרחק מזה, דאם בגרים אמתים אמרו חז”ל שקשים לישראל כספחת מה נענה לגרים גרורים כאלו שאין לבם לשמים כלל.

In no. 19 he discusses if a married woman becomes insane and has a child with someone other than her husband, if the child is a mamzer.

In no. 28 he responds to a rabbi in a Far East Russian community in which there were no Sabbath observant people other than the rabbi’s family. This created problems when it came to writing a get as one needs kosher witnesses and also the sofer cannot be a Sabbath violator. R. Kiseleff argues that since everyone in the town violates Shabbat, these people are not included under the halakhic definition of a “public Sabbath violator,” which means that one violates Shabbat in front of ten observant Jews. Therefore, none of the many gittin arranged by the questioning rabbi’s predecessor are to be regarded as pasul. At the end of his responsum, R. Kiseleff notes that in Siberia there is a big problem when it comes to gittin, as many places have no rabbi and the local shochet arranges the get. Needless to say, these shochetim were often not learned at all in this matter, and this could create major halakhic complications. R. Kiseleff therefore suggested that no one should be authorized to slaughter in Siberia until he learns the laws of gittin and is given an authorization to arrange gittin.

In nos. 29-30 he deals with a case of a man who gave a get and afterwards claimed that he was forced to do so, as he was beaten and the people beating him said that if he doesn’t give the get they will kill him. R. Kiseleff writes that the get is valid as the man would not have taken the threat seriously. In support of his assumption, he cites R. Moses Isserles who states with reference to a different case that Jews who threaten to kill another Jew are only trying to scare him, “as Jews are not murderers.”[8] R. Kiseleff sent his responsum to R. Meir Simhah of Dvinsk, and the latter disagreed with R. Kiseleff. R. Meir Simhah argued that contemporary “wild” young Jews are indeed capable of killing someone, and thus when threatened by them the man being pressured to authorize the get certainly would have taken this seriously.

דבחורי ישראל הפרוצים בזמנינו חשידי גם אשפ”ד

Here is another story about Harbin told by R. David Abraham Mandelbaum. In 1943 his father and his friend, both yeshiva students in Shanghai, came to Harbin where they visited the university. While there, and presumably in the library, they found on one of the tables a Sefat Emet on Kodashim. The two students were very surprised, since how did this book end up in such a far-away place? They grabbed the book and quickly exited.[9]

פתאום צדו עינים ספר קודש, המונח על אחד השולחנות. הבחורים המופתעים ניגשו ופתחו וגילו להפתעתם, שזהו הספר הק’ “שפת אמת” על סדר קדשים. התדהמה היתה עצומה, איך הגיע ספר קדוש זה למקום נידח, בעיר חארבין שבסין הרחוקה?! אפס, הם לא חשבו הרבה, שמו את הספר באמתחתם, והסתלקו חיש מהר מן המקום כמוצאי שלל רב.

The story as told is quite shocking to me and I am surprised that it was reported, for how was this not thievery? Presumably, the university acquired the book from one of the local Jews who donated it. Or perhaps at the time the yeshiva students were visiting the man who was studying the book had gone out to the restroom or he had left the book there from a previous visit. If such was the case, when the man returned he would have been very upset to find that his book was taken. It appears that the two yeshiva students simply felt that they had a right to take the book, as it did not belong in a Chinese institution.

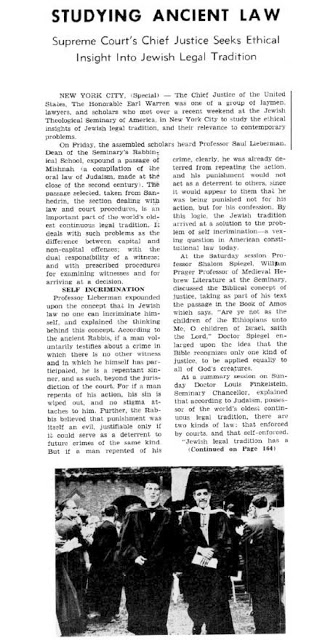

This reminds me of how many years ago I walked into the library of the Jewish Theological Seminary and saw that they had installed an anti-theft system to prevent anyone from removing a book without it being checked out. Upon inquiring I was told that this was necessary as some people thought it was OK to take books from the library, as they felt that they were “liberating” the books from the clutches of those who had no right to them, that is, the Conservatives. I never took that claim seriously and always assumed that a thief is a thief, and the people stealing the books – no matter how big their kippot or how long their beards – did not have any religious justification worked out. Subsequent experiences have shown me that these sorts of thieves will steal from anyone if given the chance, even if it means pretending to be kollel students. (I won’t elaborate further, but some European readers will know what I am referring to). But in the case from Harbin, it seems obvious that the reason for taking the book was precisely because the yeshiva students felt that there was no reason for the Sefat Emet to be in a Chinese institution. As mentioned already, I do not see how this can be justified halakhically, as we are not talking about a Jewish book that was, for example, confiscated by the government for anti-Semitic reasons.[10]

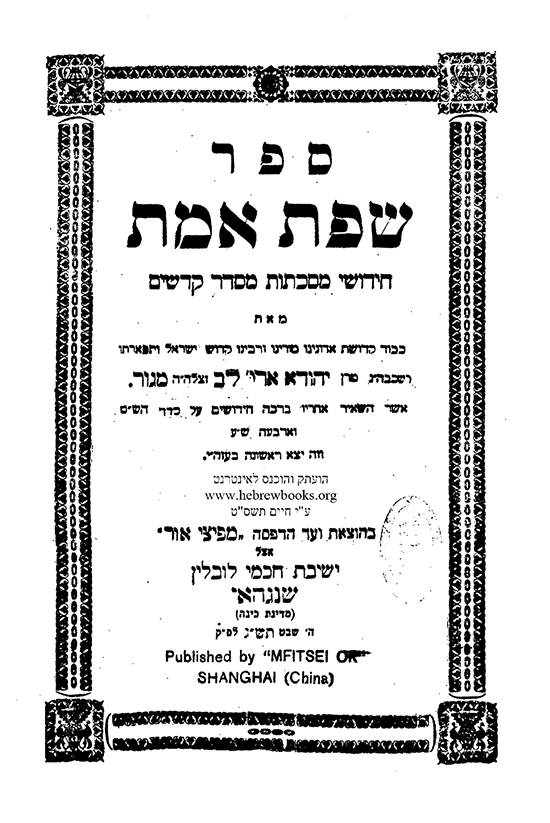

After the yeshiva students returned to Shanghai with the Sefat Emet, it was then reprinted there. Here is the title page.

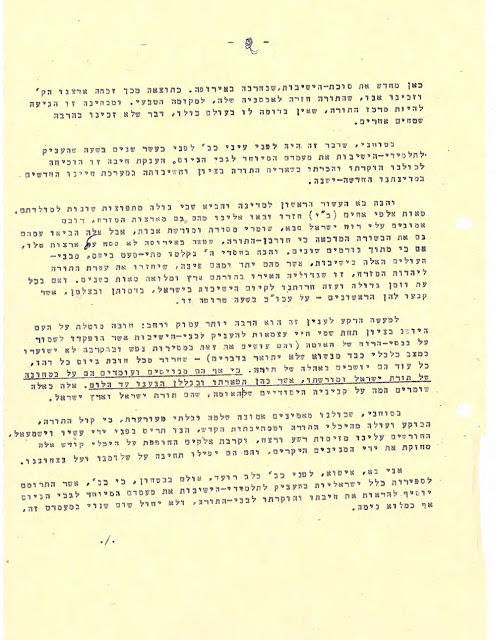

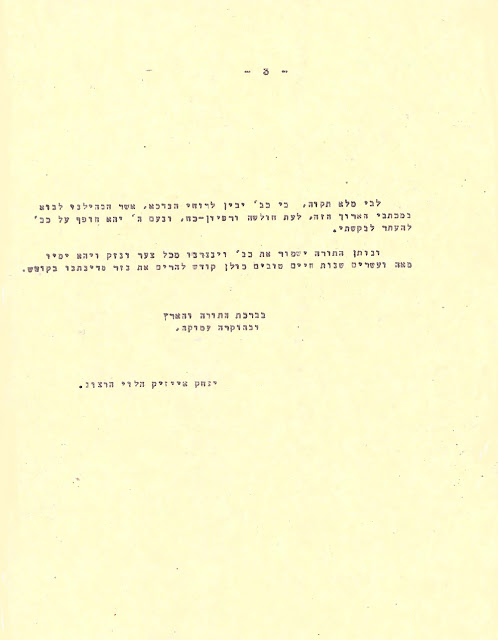

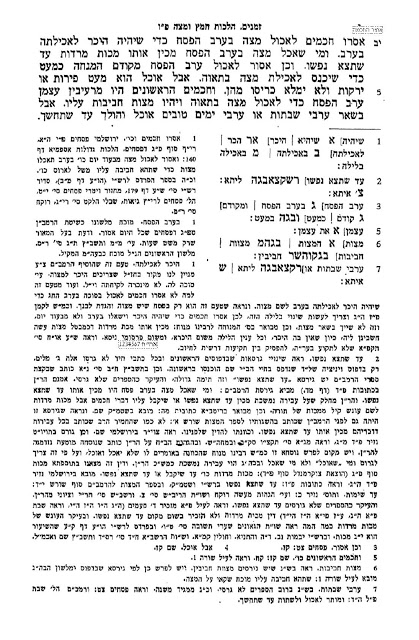

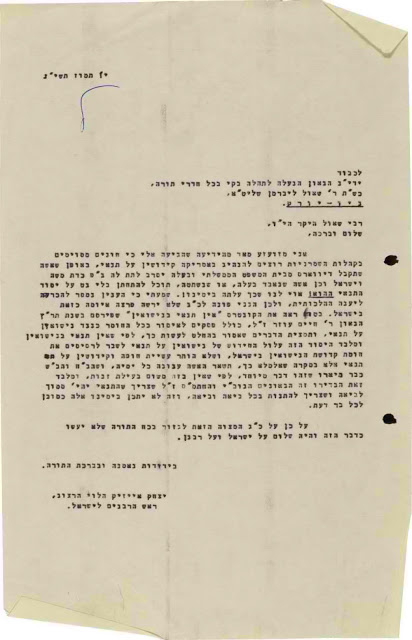

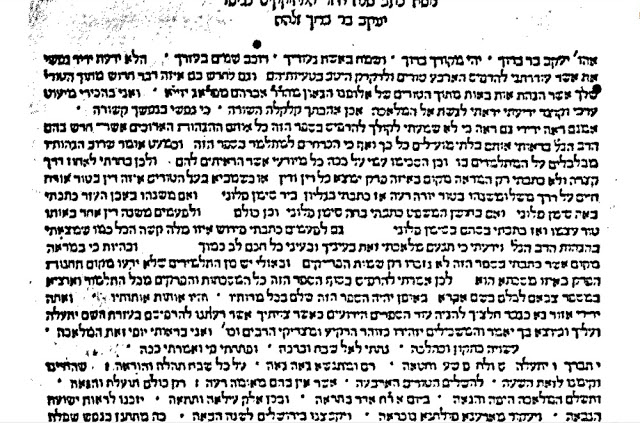

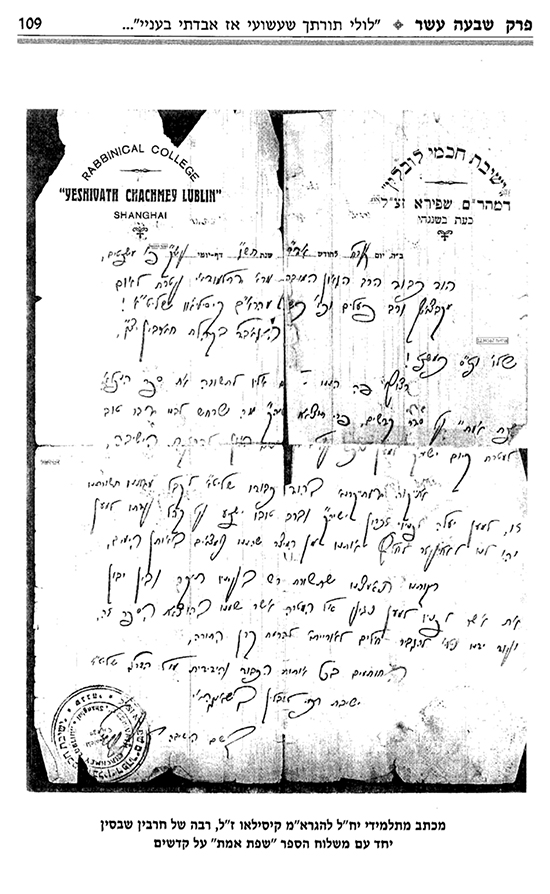

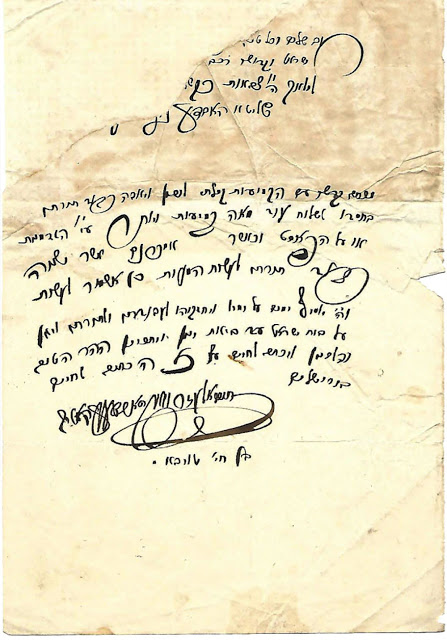

They also sent a copy of the book to R. Kiseleff, and here is the letter that accompanied the book.[11]

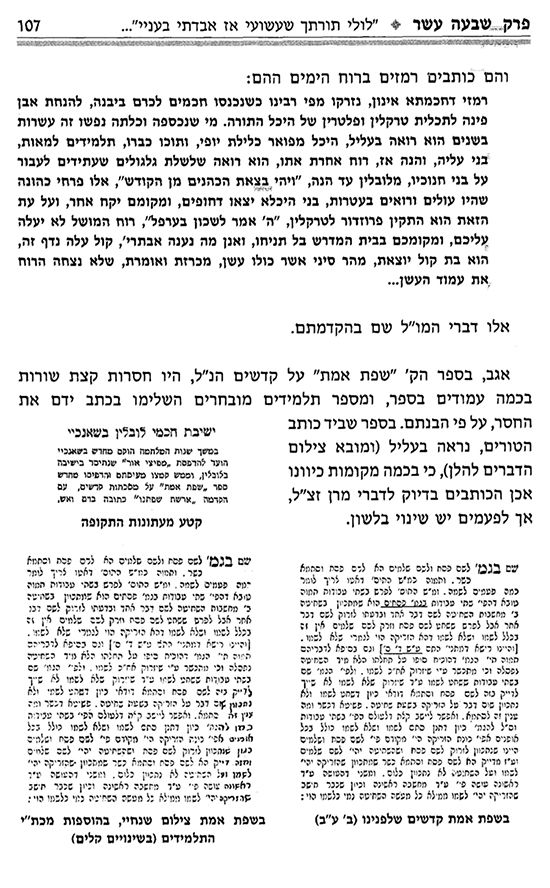

Interestingly, the copy of Sefat Emet that they used to reprint the book was missing some words. They therefore added by hand what they thought were the missing words. The following appears in R. David Abraham Mandelbaum, Giborei ha-Hayil, vol. 2, p. 107.

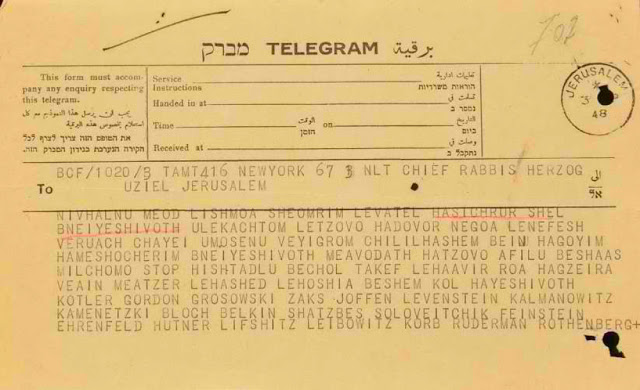

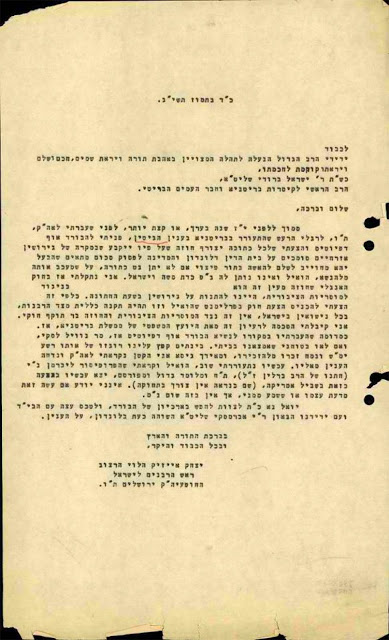

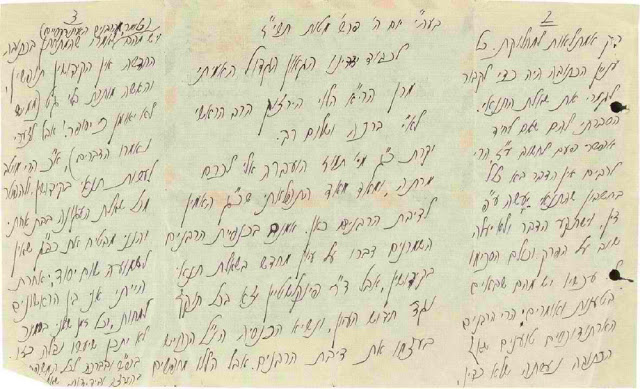

As is well known, when the Mir yeshiva reached Japan there was a lot of confusion about when to observe Shabbat and especially the upcoming Yom Kippur. Although there was already a local community there that observed Shabbat on Saturday, the Hazon Ish had informed the yeshiva that they must observe Shabbat on Sunday. R. Yehezkel Levenstein, the mashgiach of the Mir yeshiva, wrote to R. Kiseleff asking him specifically what to do about Yom Kippur, and he included a copy of the Hazon Ish’s letter explaining his reasoning. It is interesting that even after receiving the Hazon Ish’s letter R. Levenstein felt the need to consult with R Kiseleff, who was, as we have seen, regarded as the mara de-atra of the Far East.[12]

R. Kiseleff did not accept the Hazon Ish’s position. He told R. Levenstein that the question of Yom Kippur is no different than Shabbat, and they should keep the day that is currently being kept. R. Kiseleff was particularly worried that moving the Shabbat to Sunday, when it had previously been observed on Saturday, could lead to a lessening of Shabbat observance among the general Jewish population:

ורע עלי המעשה ששמעתי שמקצת מן הפליטים בקאבע קראו בתורה ביום א’ והתפללו תפלת שבת, ביחוד היא דרושה זהירות מרובה בענין זה בתבל כו’. ועתה כאשר נמצאו חרדים לדבר ד’ דוחים את השבת ליום א’ חג הנוצרים, יקל ענין שבת בעיניהם לגמרי, ויאמרו התירו פרושים את הדבר, ויצא מזה מכשול גדול אשר קשה יהי’ לתקן. לכן נלך מדרך זה חדש כזה אסור מן התורה בכל מקום . . . וכל המשנה ידו על התחתונה.

R. Aryeh Leib Malin also wrote to R. Kiseleff, and R. Kiseleff replied to him saying the same thing and sharply rejecting the Hazon Ish’s opinion.

בערב ש”ק העבר הרציתי מכתב להרב ר’ יחזקאל לעווינשטיין שליט”א בתשובה על מכתב הרב חזון איש, בו הודעתי טעמי ונימוקי שלא אסכים לפסק דינו על דבר דחיית יום השבת ביאפאן ליום א’ . . . כי דבריו בנוים על יסוד רעוע ובלתי ברור ומוסכם . . . ובלי ספק יגרום חלול שבת ותשתכח תורת שבת לגמרי . . . והריני מורה שיהודי יאפאן ישמרו שבת ומועדים ככל היהודים [במזרח הרחוק].

One wonders how R. Kiseleff would have reacted had he known that according to R. Simhah Zelig Rieger even in Harbin Jews should avoid Torah prohibitions on Sunday.[13]

והרי הישראלים בחארבין שהיא מארץ חינא אינם מתנהגים כבעל המאור, נראה שלענין התפילה שהוא ענין דרבנן לא נשנה ממנהג הישראלים היושבים שם. ולענין איסור דאורייתא יש לחוש לדעת בעל המאור שהשבת מאוחרה לשל ירושלים

I earlier mentioned R. Kiseleff’s book of derashot, Imrei Shefer. In addition to the typical derashot one would expect in such a volume, it also includes eulogies for the Hafetz Hayyim and R. Kook. Regarding R. Kook, R. Kiseleff tells us that they were at the Volozhin yeshiva together and R. Kook was regarded then as one of the yeshiva’s outstanding students. He also records a talmudic question that R. Kook asked that R. Kiseleff tells us became the talk of all the students. Also included in the book are speeches R. Kiseleff gave on the twentieth and twenty-fifth anniversaries of Herzl’s death. He describes how thanks to Herzl many Jews who were entirely removed from Jewish life and ready to assimilate began to feel pride in their heritage and reconnect to their people.

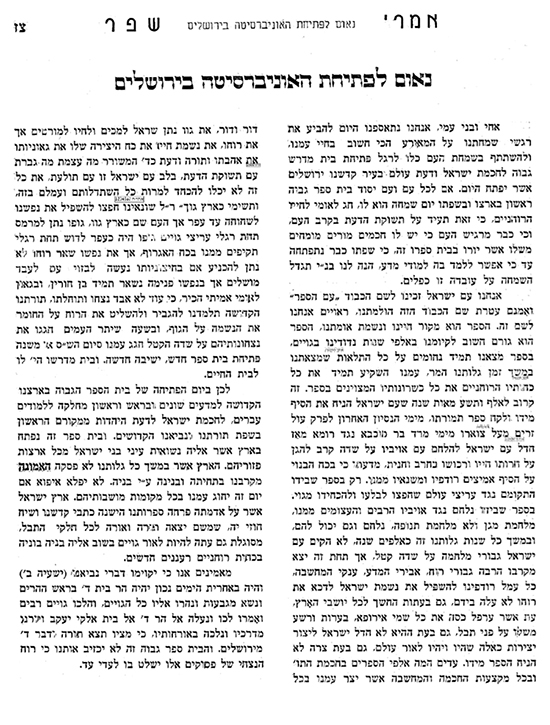

Also included in the book are speeches he gave in honor of the Balfour Declaration and in memory of Nahum Sokolow and the victims of the 1929 massacres in the Land of Israel. Especially noteworthy is the speech found on p. 97, which celebrates the opening of the Hebrew University.

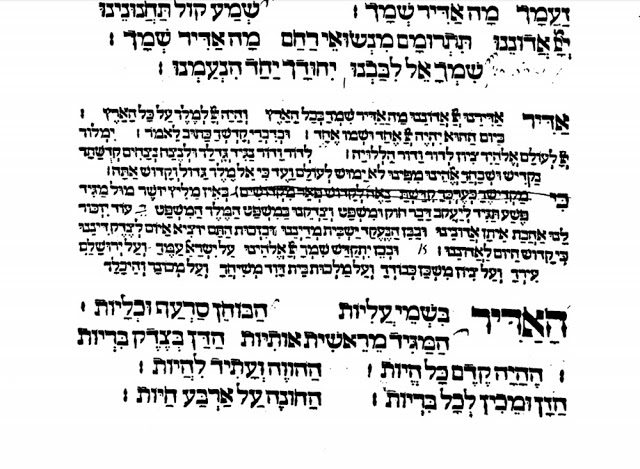

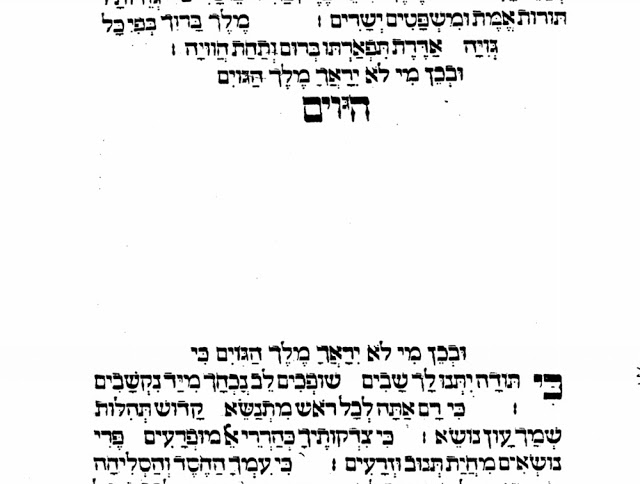

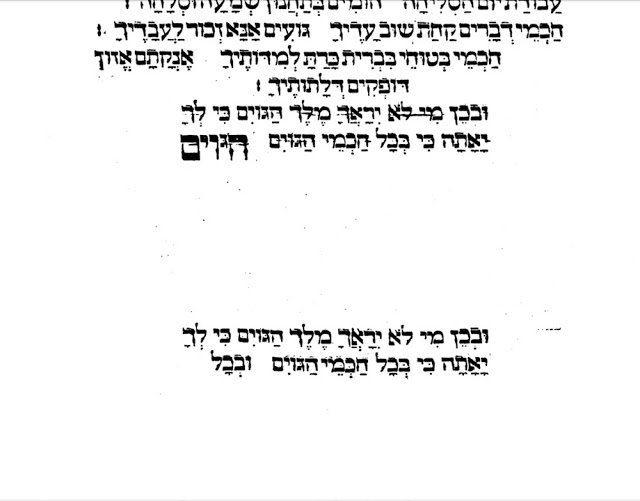

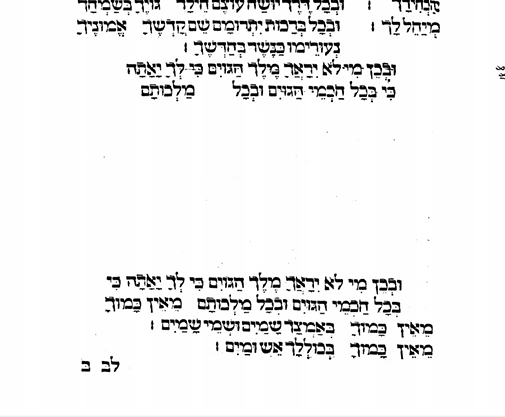

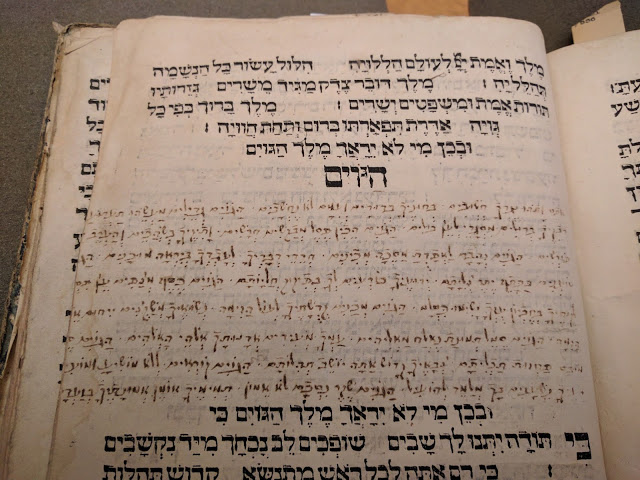

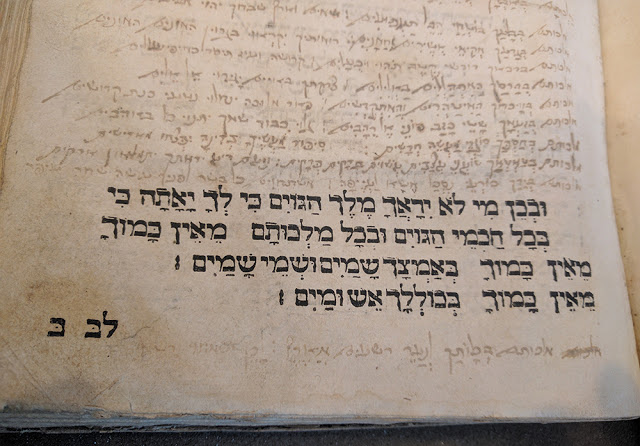

Many readers know about R. Kook’s speech on this occasion, and how he was attacked for supposedly applying to the university the verse, “For Torah shall forth from Zion, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem” (Isaiah 2:3, Micah 4:2).[14] While R. Kook never used this verse with reference to the Hebrew University, R. Kiseleff did, as you can see from the above text.

* * * * *

It has been a while since I had a quiz, so here goes. In the current post I mentioned the prohibition of Torah study on Tisha be-Av. This is an example where the halakhah of Tisha be-Av is stricter than that of Yom Kippur. Many authorities rule that there is also something else that is forbidden on Tisha be-Av but permitted on Yom Kippur. Answers should be sent to me.

Many wrote to me that it is forbidden to greet someone on Tisha be-Av but not on Yom Kippur. Greeting is forbidden on Tisha be-Av due to the halakhot of mourning. However, this is forbidden according to everyone, and in the question I asked for an example of something that according to “many authorities” is forbidden on Tisha be-Av but permitted on Yom Kippur. If you pointed to something that is forbidden by “all” authorities (i.e., standard undisputed halakhah), this is not the correct answer.

A number of people also wrote to me that on Tisha be-Av one does not sit in a regular chair, unlike on Yom Kippur. Yet contrary to popular belief – and based on the emails I have received, it is indeed a quite popular belief – there is no halakhah that one must sit on the ground on Tisha be-Av. Rather, this is a minhag, not a law, and because it is a minhag we do not sit on the ground the entire day.[15]

The correct answer, which was sent to me by Brian Schwartz and Abe Lederer, is that many authorities hold that it forbidden to smell spices on Tisha be-Av, but this is not the case on Yom Kippur. In fact, smelling spices is recommended on Yom Kippur as a way to increase the number of blessings recited on this day, so that one can reach one hundred.[16]

While this is the answer I had in mind, Peretz Mochkin sent me another answer. If one has a seminal discharge on Yom Kippur, most poskim, including the Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 613:11, hold that he cannot go to the mikveh on this day. However, there are a number of significant authorities who hold that he may do so. When it comes to Tisha be-Av, there is agreement among halakhic authorities that it is forbidden to go to the mikveh after a seminal discharge.[17] However, this does not really answer the quiz question, since the question spoke of something that is permitted on Yom Kippur but forbidden on Tisha be-Av, and as noted, most poskim, at least in recent generations, forbid going to the mikveh on Yom Kippur in the case of a seminal discharge.[18]

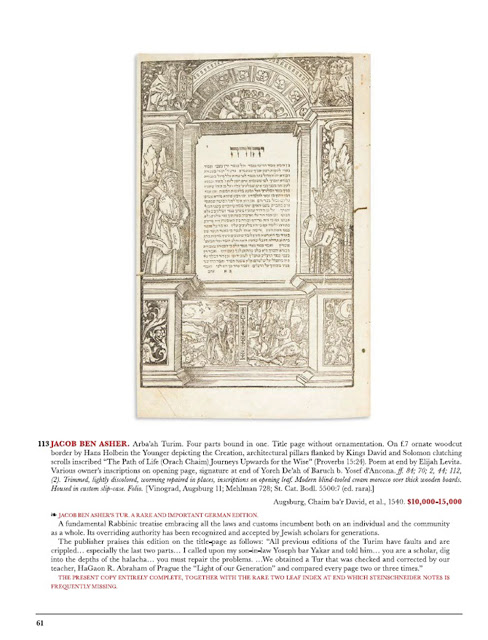

________________________________