Rabbis and Communism

By

Marc B. Shapiro

I had intended my newest post to be on the Rav’s famous essay “Confrontation,” but I recently received the latest issue of Tradition with Rabbi Yitzchak Blau’s article “Rabbinic Responses to Communism,” so let me make a few comments about it. First, I must say that it is a good read, like all of Blau’s writing, and I was impressed with the range of topics he attempts to tackle. My only suggestion for improvement would have been to examine the larger context of Jewish communist anti-clerical sentiment, which made it very hard for the rabbis to be sympathetic to communism.

Yet this anti-clerical feeling did not arise in a vacuum. Quite apart from the traditional Marxist aversion to religion, the rabbis, like their non-Jewish religious counterparts, were generally aligned with the aristocracy, who paid their salary and took their sons as marriage partners for their daughters. The rabbis were thus seen as standing in the way of economic justice. In fact, there has been a long plutocratic tradition in the Jewish world, which meant complete disenfranchisement of the poor from all communal decisions. I don’t know of any Jewish community in history where people who could not afford to pay taxes were given communal voting rights. (This would be the modern equivalent of not giving welfare recipients the right to vote – wouldn’t the Republicans love to make this the law of the land!)

R. Samuel de Medina goes so far as to argue that the wealthy are qualitatively superior to the poor, citing in support of this horrible notion Eccl. 7:12: “For wisdom is a defense, even as money is a defense.” For him, money and wisdom are two sides of the same coin. [1] He also gives another proof to support his pro-wealth point of view. Gen. 41:56 states: “And the famine was over all the face of the earth (פני הארץ).” Upon this the Midrash comments that the face of the earth refers to the rich people (Tanhuma, ad loc.). From this we see, says de Medina, that the rich are at the head of the community and everyone else in the rear, not a position from which one leads.[2] As he puts it (and note how the poor and the ignorant are treated as one group):

Accepting the will of the majority, when that majority is composed of ignorant men, could lead to a perversion of justice. For if there were one hundred men in a city, ten of whom were wealthy, respected men, and ninety of whom were poor, and the ninety wanted to appoint a leader approved by them, would the ten prominent men have to submit to him regardless of who he was? Heaven forbid, this is not the accepted way (“the way of pleasantness”).[3]

None of this means that de Medina was insensitive to the needs of the poor. This was not the case at all, and he has a responsum in which he requires people to contribute to the building of houses that will be used, among other things, for poor visitors to spend the night.[4] Yet we see in him a sense of paternalism that was common in traditional societies all over the world, and was one of the factors which convinced the lower class that it was time to take matters into their own hands.[5]

When dealing with anti-clericalism in Russia, we must also not forget the masses’ long memory of how some (many?, most?) rabbis were silent during the era of the chappers. This was when children were grabbed for 25 years of military service in the Cantonists, often never again to see their parents and usually succumbing to incessant pressure (including torture) to be baptized. Yet it wasn’t the children of the rich or the rabbis who were taken, but the poor children. Jacob Lifshitz’ defense of the way the Jewish community dealt with the Cantonist tragedy – which he regards as worse than even the destruction of the Temple![6] – and his insistence that no one can judge the community leaders unless they themselves had been in such a difficult circumstance, is something we must bear in mind.[7] Yet all such ex post facto justifications would have no impact on the outlook of those that actually suffered during the Cantonist era, and it is no wonder that many of the common people would not regard the rabbis in a sympathetic light. The rabbis were certainly able to come up with a justification why their sons, the future Torah scholars, should not be taken to the army, just as they continue to make this argument. Yet this would only serve to show the masses that some children’s blood was indeed redder than others.[8]

In his memoir of this era, Yehudah Leib Levin wrote:

“I was relatively calm and personally did not fear the chappers, because my father was an important landlord, distinguished in Torah and highly regarded by everyone. My mother was the daughter of the most famous tzaddik (righteous person) of his generation, Rabbi Moshe Kabrina’at. And I, I was one of the “good children,” a prodigy the likes of whom were not touched by the hand of the masses. Free both of fear and of schoolwork, because the teachers and pupils had all gone into hiding and the chedarim [schools] were closed, I wandered daily around the city streets seeing the little “Russians,” and my heart burst when I realized they were in the hands of non-Jews, who forced them to eat pork – oh dear me!”[9]

Elyakum Zunser was seized when he was away from his hometown. Many years later he wrote:

“Many private individuals engaged in this traffic, seizing young children and selling them to the Kahal “bosses.” Reminiscent of the sale of Joseph by his own brothers, these betrayals occurred daily. Lesser rabbis of small towns assented to such transactions, rationalizing that it was more “pious” to save the children of their own towns than to concern themselves with the fate of strangers.

“Though many important rabbis wept at these outrages, most dared not protest. They were afraid of the consequences if the Jewish community would defy the Tsar’s quota. The rabbis held their positions at the discretion of the Kahal leaders and feared the consequences of displeasing them. They were afraid to be denounced to government officials and exiled to Siberia.[10]”

Michael Stanislawski notes that in one community the communal leaders wanted to grab a poor tailor since he wasn’t observant, but the local rabbi forbid it. Stanislawski also tells us that in Vilna the communal leaders had their sights on a larger prize.

[T]he traditionalist kahal authorities later attempted to forestall the opening of the government-sponsored rabbinical seminaries by drafting the sons of several of its proposed teachers, but this was discovered by the local administration and forbidden.[11]

He also quotes the Hebrew writer Y. L. Katsenson, who describes his grandmother’s shock when she discovered that the chappers in her town were not Gentiles:

No, my child, to our great horror, all khappers were in fact Jews, Jews with beards and sidelocks. We Jews are accustomed to attacks, libels, and evil decrees from the non-Jews – such have happened from time to time immemorial, and such is our lot in Exile. In the past, there were Gentiles who held a cross in one hand and a knife in the other, and said: “Jew, kiss the cross or die,” and the Jews preferred death to apostasy. But now there come Jews, religious Jews, who capture children and send them off to apostasy. Such a punishment was not even listed in the Bible’s list of the most horrible curses. Jews spill the blood of their brothers, and God is silent, the rabbis are silent. . . .[12]

What is incredible is that after all the pressure to convert, some Cantonists remained Jewish. In fact – and here I mention something that I only learnt after my book on R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg was published – Weinberg’s grandfather was a Cantonist. His father was also a soldier in the post-Cantonist Czarist army.[13] In the book I mentioned that Weinberg’s family was undistinguished, yet if I was writing it now I would speak about how the two generations of army service signifies that this was in fact a very low-class family, and shows how significant Weinberg’s rise to fame was. As I pointed out, while in theory the yeshivot were equal-opportunity institutions, in reality the aristocratic element in them was generally well established and self-perpetuating.[14]

In a strong defense of the rabbis against the charge that they collaborated with the rich people in order to ensure that the poor were taken, R. Moses Solomon Kazarnov calls attention to all that the rabbis did to defend the children of the lower class.[15] But he acknowledges that the rabbis would hand over the non-religious kids, including their own![16] (While I have no doubt that the rabbis joined with the parnasim to hand over the non-religious youth, it strains imagination to believe that there were more than a few who did this with their own irreligious sons.) As Kazarnov puts it (51-52, in words that must cause loathing in any contemporary parent, and I would assume in virtually all parents even one hundred years ago):

והרבנים איפא כבנים נאמנים לתלמודם הורו למעשה את אשר מצאו כתוב להלכה, ותמיד הורו לא אך לאחרים, אך גם לעצמם, אם בניהם לא נהגו כשורה, לנדותם להבזותם ולתת גם את חלקם לטובים מהם; כמה אבות רבנים או חרדים גרידא הנך זוכר קורא יקר, אשר בניהם יצאו לתרבות רעה ואשר התפללו לה’ תמיד כי יחמול ה’ עליהם ויקח את בניהם אלה מהם, כמה מהם השתדלו בעצמם להשיג את בניהם שנתפקרו למען מסרם לצבא תחת יתר בניהם הרודים עם א-ל?

Talk about conditional love! I don’t even want to imagine what it did to the mental state of a child who knew that his father would hand him over to the Czar’s army if he decided that he no longer wanted to be Orthodox. Kazarnov continues:

ואם כן אפוא מי זה יאשימם על הוראתם למסור למלכות לעבודת הצבא את החטאים תחת הכשרים? . . . הלא לא עשו לבני העניים יותר מאשר עשו לבניהם המם. את הכשרים שמרו כבבת עינם, אם שלהם ואם של אחרים, ואת החוטאים מסרו לצבא אם מירכם יצאו או מירך זולתם! . . . במאכלות אסורות ובנבלות, זמה ורשע, בזדונות כאלה שמו החרדים את פניהם להמעיטם מקרב עמם, מקרב משפחתם ומקרב בני ביתם, ומה היא כל החרדה הזאת?

Concerning the general issue of the rabbis being allied with the wealthy, Dan Rabinowitz called my attention to what R. Judah Margaliot wrote in his Beit Middot:

Some of the leaders of Israel do not think of the glory of their Creator but only of their own. They employ all their power merely to terrorize the community. [He then elaborates on how they do this] . . . Do not think that one can turn for help to the great figures of the generation, to our rabbis, whose duty it is to be the protectors and defenders of the people. For they are in league with the oppressors, walk together with the powerful men and rulers of the city, become collaborators of every mischief-maker, give protection to every swindler. They exploit the rabbi’s title and authority for all kinds of evil deeds. Everything obtains the approval of the community rabbi. He who ought to be the guardian of righteousness and justice becomes the protector of robbers and bandits. The righteous judge joins the league of the swindlers. . . . . And these are our judges and lawgivers! Calmly they look on at the robberies and injustices that take place in the community and flatter the rich and powerful from whom every quarrel and plague come.[17]

Returning to the issue of poverty, which de Medina sees as a disqualifier for communal leadership, we can also find more positive evaluations of it. Nedarim 81a tells us not to neglect the children of the poor, for the Torah goes out from them. If you examine the commentaries on this passage you will certainly find those who point out that it is easier for a poor person to study Torah, as he does not have the same attachment to the material world as does the wealthy man, and it is this attachment that prevents one from focusing on Torah. I read these sources as designed to be encouraging. In other words, they are ex post facto judgments of the positive that can be found in poverty, so that people in this unfortunate state don’t think that all is lost.

Yet in the entire history of the Jewish people I don’t know of any source that says that it is good to be poor, and that this is something that one should strive for. In fact, the Talmud states that one who is poor is like one who is dead (Nedarim 64b), and puts poverty in the same category as childlessness, leprosy, and blindness, all things that we hope we never have to deal with. Similarly, R. Phineas b. Hama stated: ”Poverty in one’s home is worse than fifty plagues” (Bava Batra 116a). In Eruvin 41b extreme poverty is listed as one of the three things that “deprive a man of his senses and of a knowledge of his Creator.”

The notion that it is harder for a rich person to get into heaven than to put a camel through the eye of a needle has never been a Jewish teaching, and Jews have regarded wealth as a blessing. It is a challenging blessing, but a blessing nonetheless.

Yet when questioned by those who pointed out how difficult poverty is for the kollel students in Israel, R. Aryeh Leib Steinman responded with what, to my knowledge, is a completely new approach, one which idealizes poverty in a manner not very different than the Christian notion of “Blessed be ye poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.” (Luke 6:20):

While everyone must distance themselves from unnecessary expenditures and luxuries just as they would be careful of fire, Bnei Torah have an especial obligation as the simple life is recommended for acquiring Torah, and they have it better if they live a life of simplicity and tsnius, and even poverty and want. It says: This is the way of Torah – eat bread with salt. But it is important to stress that what is necessary is strengthening emunoh and dedication to Torah. One should definitely not look for solutions that might cause avreichim to leave learning, G-d forbid.

I was asked if it would be a good idea to open offices for chareidi men in the large chareidi cities so that they could work in an appropriate atmosphere. It is obvious that the idea is a bad one though the intentions are good. The fact that the workplaces would be especially suited to the needs of chareidi men, and set up by chareidi people, might encourage people in difficult financial situations to leave learning. It is a spiritual stumbling block for the community at large. It would be terrible even if it would cause just one man to leave full-time learning. . . .

What are the effects of poverty? The answer is that it is better to be poor than to be rich, as Torah comes forth from the poor; they are the ones that become talmidei chachomim. The Jewish People has always undergone difficult trials. Historically, it’s been the poor people who have maintained their commitment to Judaism, despite the difficulties. It was among the rich people that some failed to withstand the temptations and trials. They are the ones that lost their children and grandchildren to Torah. It was the poor who remained especially steadfast in their dedication.

I have personally witnessed, and history testifies, that in all of the places where people learned Torah in poverty, they were able to maintain the Mesorah. In the places where the people had a comfortable standard of living, their learning was not immune to the Haskalah’s influences and many abandoned the Jewish and Torah way of life.[18]

Returning to Blau’s article, I was happy to see that he cited R. Jacob Emden who expressed admiration for shared property. I would just note that as with so many other issues in his writings, Emden had an alternate opinion as well, and here he comes out looking like his contemporary, Adam Smith. Emden explains how poverty is essential to a successful economic order. He notes that without the motivating factor of those who are in need – what Gordon Gekko would call “greed”[19] and what others will call “self-interest” – no economic progress will ever be made. If people are not able to improve their economic state, they will not take the risks that stand behind all new ideas and discoveries, which are precisely what keeps the economic engine of a society going. Communism, which took away the hope of personal gain, stifled all of this creativity.

Showing keen insight, Emden writes that if everyone had sufficient economic security, no one would travel on ships to far-away places and bring back the goods that are so important to people, no one would agree to do the back-breaking work required to build society’s great structures, and no one would take the time to come up with new inventions such as clocks and מחזות, which Azriel Schochet[20] suggests means glasses but I think telescopes is just as likely.

The passage appears in Birat Migdal Oz, 138b, but since the edition I have access to (on Otzar ha-Hokhmah) does not have page nos., I will cite it as it appears in Schochet, Im Hillufei Tekufot, 224-225:

והפלא מהשגחת הבורא הפרטית לתועלת עולמו ולהשלים תקנת בני אדם דרי תבל למלא חסרונם בהמצא בהם עניים ודלים. כי זולתם לא היתה הארץ נעבדת לתת יבולה ופריה, ולא היו מתגלים מחצבי הכסף והזהב ואבנים יקרות וסממני הרפואה ומיני הצבעים הנחפרים מן הארץ להודיע טובה ושבחה ושפעה הרב, לא תחסר כל בה. ואם היו כולם שבעים ומושפעים בשוה לא היה אחד מהם טורח להשיג דבר מן הדברים הנזכרים, ואצ”ל שלא היה שום אדם מסכים לרכוב אניות ולדרוך אניות להביא לחמו ממרחק ולמלא חסרון המדינות נעדרי התבואות והדברים היקרים וראשי בשמים והסמים הפשוטים, ולא היה מי מהם שירצה להעמיס על עצמו המלאכות הכבדות כבנית הבנינים הגדולים והיכלות תמלכים ומגדלים, ערים בצורות וחפירות הבורות והבארות, והיה העולם שמם. וכל שכן שלא היה אחד טורח בשכלו ובכח ידו להמציא תחבולות ואומניות נפלאות, כמו כלי השעות והמחזות והדומה להם מהאריגה והציורים ופתוחי חותם, והרבה מה שיארך זכרו, ולא היה ניכר שוע לפני דל, ובסיבת העוני ישיגו בני אדם כל הטובות הגדולות הרבות ההנה, והעני והחסר ישיג בהם די מחיתו והשלמת חסרונו ברצונו. מלבד מה שישיגו ע”י כך אורחות חיים כי יחלץ עני בעניו ע”י שנצרף בכור העוני, והעושר זוכה בו ומהנהו מנכסיו, מאיר עיני שניהם ה’.

I was also happy to see that Blau mentioned R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg’s views, although he overlooked Li-Frakim (2002 ed.), 578-582 and Kitvei ha-Rav Weinberg, vol. 2, 404-408,[21] the latter of which is devoted to Marx.

As can be expected, the rabbinic figures Blau surveys in his recent article in Tradition were no great fans of communism.[22] He writes: “My research failed to turn up a single Rabbi [!] of recognized stature who endorsed the communist program.”

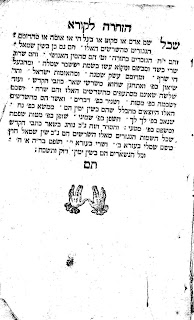

.יגעתי ומצאתי After the February 1917 Russian Revolution which brought Kerensky to power, the Orthodox formed a group called Masoret ve-Herut. It contained both Zionists and non-Zionists and was supposed to send a delegation to the All Russian Jewish Congress, which because of the Bolshevik revolution never took place. The group also envisioned itself becoming a real political power with the establishment of the new government. On the seventeenth of Tamuz, 1917, over fifty rabbis came to Moscow for discussions about this, including R. Avraham Dov Shapiro of Kovno, R. Abraham Aaron Burstein of Tavrig,[23] R. Isaac Rabinowitz of Ponovezh (R. Itzele), and R. Aaron Walkin of Pinsk. The Hafetz Hayyim sent greetings but was too ill to attend.

Since the masses did not have any property, one of the issues the new group would have to take a stand on was agrarian redistribution. With the Czar overthrown, it was possible to take not just his land but also the land that belonged to the wealthy princes, noblemen, and magnates and redistribute it, and this was certainly what the average person wanted. However, is this in accord with Jewish law? Can one confiscate another’s property? This was a subject of great controversy among the rabbis, and as can be imagined, many opposed this step. R. Itzele got up and, as recorded by R. Judah Leib Graubart,[24] said the following

החלק הפוליטי נחוץ, כי על ידו נמשוך את בני הנעורים והרחוב להסתדרותנו. גם הלא אנו רואים, כי כלל ישראל חפץ בו, בוודאי מאת ד’ הייתה זאת. וכלל ישראל הוא גבוה ונעלה מגדולי התורה. ישראל אם אינם נביאים, בני נביאים הם.

In other words, if the Jewish people think that the concentration of land in the hands of a minority is unjust and should be redistributed, even if the rabbis claim that redistribution of the land is robbery, the opinion of the Jewish people overrides that of the rabbis.[25] Certainly, all would agree that R. Itzele is a rabbi of recognized stature.

Zalman Alpert called my attention to Jacob Mark’s discussion of R. Itzele in his Bi-Mehitzatam shel Gedolei ha-Dor, 116. Mark mentions that R. Itzele was greatly respected by the radicals (which included at least one of his own sons who was arrested in 1905 for revolutionary activities).[26] He was also very interested in socialism and carefully went through Marx’s Das Kapital. He was greatly impressed by Marx’s ideas, yet Mark notes that he commented: “I cannot agree with his positions, because they oppose the Torah law that protects private property.” I don’t deny that he said as much to Mark, but as we see from Graubart’s book, at the time of the Revolution he had a different perspective.[27] As to how, from a halakhic standpoint, he could have supported redistribution of wealth if the Torah protects private property, this is not a difficult problem. After all, as far as the Rabbis are concerned, governments have the right to engage in all sorts of taxation and redistribution of wealth.[28]

Eliezer Brodt called my attention to R. Moshe Shmuel Shapiro, Rabbi Moshe Shmuel ve-Doro (New York, 1964), 134-135, who tells an interesting story about R. Menashe of Ilya, one of the great students of the Vilna Gaon. (I can’t say whether the story is apocryphal.) R. Menashe was greatly bothered by the terrible poverty in the Jewish community and came up with a revolutionary idea long before Marx. He proposed organizing a meeting of all the great rabbinic and lay leaders in the Jewish community, and their job would be to divide the Jewish wealth evenly. By doing so, the poverty problem would be solved and all would be equal. It is said that he turned to R. Hayyim of Volozhin and asked him to put his stature behind such a gathering. R. Hayyim replied that he is willing to be involved in one half of the program, i.e., the part where the poor receive the money, but the second part, in which the rich have to give up their money, he leaves to R. Menashe. Supposedly, R. Menashe understood from this answer that his plan had no hope.

R. Judah Leib Ashlag was another great rabbi who supported communism (see

here ). It is very ironic that today Ashlag’s torch is carried by a few capitalist entrepreneurs, who have become very rich through the Kabbalah Centre.[29]

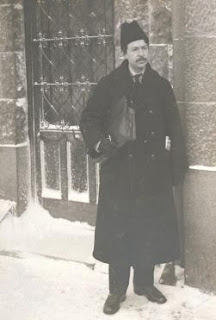

Isaac Steinberg, while not a rabbi, is a figure that should be mentioned. He was a leader of the Social Revolutionary Party and served as commissar for law in the first Soviet government. There is a lengthy article and picture of Steinberg in the Encyclopedia Judaica. Here is another picture of him.

Steinberg was also an Orthodox Jew. His ability to combine revolutionary views and Torah might be due to the influence of his teacher, the brilliant Rabbi Shlomo Barukh Rabinkow, who was himself “a convinced socialist and revolutionary.”[30]

Abraham Bick (Shauli) is also worth mentioning. He was the brother of R. Moshe Bick, who was a leading posek in the Bronx and later in Boro Park. (This is incorrect. A family member has pointed out that they were distant cousins, not brothers). An early musmach of RIETS (in the days of R. Moshe Soloveichik), he was well accepted in the haredi world.[31] (I recall how happy I was to once stumble upon his shul in Boro Park, having finally found a place that davened nusach ashkenaz.) The Bick brothers were direct descendants of R. Jacob Emden, and Abraham Bick is known for publishing a new edition of Emden’s autobiography, Megilat Sefer. He also published a biography of Emden, Rabbi Yaakov Emden (Jerusalem, 1974).

As has already been pointed out on at the Seforim blog,[32] Jacob J. Schacter commented about Bick’s biography that “is uncritical, incomplete and simply sloppy. It is barely more useful than an earlier historical novel in Yiddish about Emden by the same author with the same title published in New York, 1946. In general, all of Bick’s work is shoddy and irresponsible and cannot be taken seriously.” In R. Meir Mazuz’s recently published Arim Nisi (Bnei Brak, 2008), 42-43, he strongly criticizes Bick’s edition of Emden’s Zoharei Ya’avetz (Emden’s notes to the Zohar). He was unaware that R. M. M. Segal-Goldstein has an article in Or Yisrael 43 (5756): 208ff., in which he deals with Bick’s fraudulence in this work, and much more. Following this article, Yehoshua Mondshine added his condemnation as well.[33] Schacter’s judgment is that Bick’s work is “shoddy and irresponsible.” While there is certainly a good deal of this, the more serious problem with Bick is that he was a forger, pure and simple. (Unlike Chaim Bloch, he didn’t forge complete works, only small sections of otherwise authentic works)

Bick also has an article on religious life in the Soviet Union[34] and he co-edited a volume of Torah writings of rabbis in the Soviet Union.[35] Yet what is most fascinating is that he himself was a communist, and even published a Hebrew volume on Marx.[36] In his early years he also published two volumes on religious socialism, both of which had contributions from Steinberg.[37] According to one source, his attraction to communism began when he was a young man in Eretz Yisrael, during which time he was also close to R. Kook.[38] In 1947 Bick was even identified in Congressional testimony, before the Committee on Un-American Activities, as being on the board of the communist School of Jewish Studies (Institut far Yidisher Bildung) located in New York.[39] In 1950 this institution was placed on the Attorney General’s list of Totalitarian, Fascist, Communist and Subversive Organizations.[40] During World War II Bick was also involved with the Jewish Committee for Assistance to Soviet Russia.[41]

R. Chaim Ozer Grodzinski in a 1923 letter refers to someone whom the communists called “the Bolshevik Rrabbi.”[42] R. Chaim Ozer speaks of him with contempt, and regards him as a phony. Yet this rabbi obviously had an audience, as R. Chaim Ozer writes as follows:

וגם בהיותם פה דרוש דרש כמה פעמים והי’ מטיף להתאחדות הסוחרים הקטנים ללמוד מלאכה, ובתוך הדברים הרבה להטיף בשבח הקומוניסטים ולהביא ראי’ מן התורה ומדברי חכז”ל לשיטתם.

Wouldn’t it be interesting to know whom R. Chaim Ozer was talking about? The reason we don’t know is because the editors of the volume have removed the name. Unlike the Chazon Ish’s letters, names are not generally removed in the letters of R. Chaim Ozer. Does the fact that in this case the name was removed mean that we are dealing with someone who is not an unknown figure, maybe someone who later regretted his actions and became a more conventional rabbi? I have no doubt that examination of the Yiddish press of the period would enable one to identify the figure pretty easily.

In fact, thanks to Zalman Alpert’s assistance, I suspect that R. Chaim Ozer was referring to R. Chaim Faskowitz. Faskowitz studied in Eishishok, Lida, Slobodka and Brisk. He then was a preacher in Vilna and later served as a rabbi in Star-Daragi and Minsk before going on Aliya. He was known as the “Red Rabbi” for his sermons supporting the Soviet Union.[43]

Yet for the best of all quotes in this regard, one which really needs to be unpacked, no one can do better than R. Kook (Shemonah Kevatzim 1:89-90):

הנשמה הפנימית, המחיה את השטה הסוציאלית כפי צורתה בימינו, היא המאור של התורה המעשית, במלא טהרתה וצביונה. אמנם שהשטה בעצמה עומדת היא באמצע גדולה, ואיננה יודעת עדיין את יסוד עצמיותה. אמנם ימים יבאו ותהי למוסר נאמן לאמץ התורה והמצוה, במלא שיגובם וטהרתם.

האנרכיה היא נובעת מיסוד יותר נעלה מהסוציאלי[ו]ת. איננה יסוד לתורה המעשית וקיומה, כי אם להדבקות האלהית, העליונה מכל מעשה וסידור חיובי. על כן היא עוד יותר רחוקה ממקורה, שהוא עומד רחוק מאד משפלות החיים של ההוה, מהסוציאליות, ובמצבה של עכשיו, ומצב החיים של ההוה, היא פרועה כולה, למרות הניצוץ האלהי הנשגב המסתתר בתוכיותה.

Regarding opposition to communism, the following interesting passage is found in Eliezer Zweifel, Sanegor (Warsaw, 1885), 164:

הרב הגדול ר’ יוסף חיים קרא אבד”ק וולאצלאוועק יאריך ה’ ימיו, אמר לי שלדעתו כנו חז”ל את כת הקומוניסטים בשם ע”ה, והם אותה האומרים כיס אחד יהיה לכולנו והכל יהיו עמלים לאמצע, וכמו שהממלכות שבימינו מוצאות אנשי הכת הזו להורסים שלום המדינה, ולמנתקים קשרי החבורה האנושית, כן הרחיקו חז”ל את החבורה המזקת הזו, ולפי דעתו השערתו זו מבוארת היא בדחז”ל עצמה, שהם ז”ל הגדירו תאר ע”ה בזה, באמרם בפרקי אבות, שלי שלך ושלך שלי עם הארץ ע”כ. הנה כללו את כל השטה הזו במלות קצרות, ע”כ.

Returning to Graubart’s Sefer Zikaron, it is actually quite a fascinating text and an important source for Orthodox history during the final days of Czarist Russia and the post-Revolution era. In addition, he includes letters from various rabbis and descriptions of numerous figures in East European Jewish life. He also records the following joke in the name of R. Solomon Zalman Lipshitz (1765-1839), the first chief rabbi of Warsaw (217):

מחבר “חמדת שלמה”, הרב מוורשה, כתב מכתב לרב אחד ויתיארהו בשם “גאון”. וכאשר נשאל: “מה ראה על ככה, הן האיש ההוא אין העטרה הולמתו”? השיב בבדיחות: “הלא הגאונים )אחרי רבנן סבוראי) לא ידעו מה שנאמר ברש”י ותוספות וכמוהם כמוהו איננו יודע. ואם כן, הוא משרידי “הגאונים” הקדמונים.

On the previous page, Graubart asks where the practice arose of addressing people with all sorts of elaborate titles that are a standard feature of the rabbinic literary world, especially in the introductory sections of letters. His answer is very interesting and also relates to the issue of sensual medieval Hebrew poetry, which I have mentioned in a few previous posts at the Seforim blog:

וקרוב לאמת, כי זאת השפעה מן הערביים, שהיו מספיקים בגוזמאות והפרזות, וכמו שחקו אותם משוררינו הספרדים לפנים בשירי יין ואהבה, אף שהמשוררים ההם שתו יין ארבע כוסות אחת בשנה ומעודם לא טעמו טעם חטא, ורק מודה ספרותית היתה בזה.

With regard to elaborate titles and the extreme respect generally shown to halakhic authorities with whom one disagrees, it is worth noting what appears in the recently published

Or Bahir of R. Moses Samuel Glasner, concerning whom has recently been two posts on

the Seforim blog (

here and

here). He writes (25):

הסיבה לזה הוא שבדורנו השפל האמת נעדרת, ואין מי שיתחמם בעבורה כבדורות שלפנינו, ולעומת זה גדלה החנופה, ובשלה פרי רעל לדבר אחד בפה ואחד בלב, ומלא הארץ חנף וצביעות בתוארים שונים מגוזמים ומופרזים המחרידים אוזן השומע ועין הקורא.[44]

As I mentioned, Graubart’s book is fascinating reading, but I think many will be upset by the reason he gives for the exclusion of women’s testimony in court (208):

להרוג נפש או להוציא ממון מבעליו, צריך עדות ברורה ואין לסמוך על דברי נשים, שטבען נוטה לדמיונות, הזיות וגוזמאות והן רפות רוח ורכות לבב; ויוכל היות כי מה שאומרות ומעידות שראו עיניהן, הן מרבין לשער אומדות.

To support this understanding he also quotes a few non-Torah sources. One is Josephus who wrote: “Let not the testimony of women be admitted, on account of the levity and boldness of their sex” (Jewish War 4:8). He also quotes Socrates who is said to have made three blessings every day, one of which was that he was not made a woman. The other two blessings were that he was not made a barbarian or a slave – sound familiar?[45]

(To those women who are bothered by the blessing shelo asani ishah, R. Zvi Yehudah Kook has the answer, but you will have to wait until Messianic days! [Ittturei Kohanim, no. 167 (5759), 4-5]):

[ ]הברכות נקבעו על פי ההרגשה האנושית היחסית . . . לעומת זאת, ההשקפה האלהית, האמת המוחלטת, אינה ענין של הרגשה חולפת, אלא האמת הנצחית מראשיתה ועד סופה. לעתיד לבוא, כאשר גם האדם יכיר את האמת, ויהיה כולו מבחינת “הטוב והמטיב”, לא יוכל לברך “שלא עשני אשה”, שהרי אז יכיר שבניינה של האשה יותר רם, יותר אלהי ופחות אנושי, ממצבו הוא.

Following this logic, what about all those men who even in pre-Messianic days don’t regard women as second class in any way? Shouldn’t they be able to dispense with the blessing as early as tomorrow morning?)

Graubart, 65, also notes that many great scholars make simple grammatical errors וכמעט שלשון .עלגים היא סימן ללמדנות

He then tells the following joke, in the name of the Hakham Zvi, which everyone can repeat at their Passover seder.

רבים שואלים, בהגדה של פסח, למה מגנים ומחרפים את הרשע, על אמרו לכם ולא לו, הלא גם החכם אומר “אתכם” ולא “אותנו” – אך באמת, כונת החכם (הלמדן) הוא “אותנו” ורק מפני טרדתו בלמוד הגמרא והפוסקים הוא טועה בכנויים ומבטא “אתכם” תחת “אותנו” שלא בדקדוק, ואין לחשוד אותו כי בכונה אומר “אתכם”. לא כן הרשע שאיננו עוסק בגמרא, והוא מבעלי הדקדוק ויודע את ההבדל בין לכם ולו וב”דעת” שפתיו ברור מללו, אם הוא אומר “לכם” בכונה הוציא את עצמו מן הכלל.

Graubart also explains why Poland wasn’t blessed with the sort of great figures who were found in Lithuania, men who were able to be true rabbinic leaders and respond to problems as the times demanded. He places the blame with the Hasidim. In a passage that could well be written today (although it would then also have to include the contemporary Lithuanian “courts”) Graubart writes (173):

אבל “רבי החסידים”‘, אשר שפכו את ממשלתם על ההמון, קצצו את כנפי הרבנים ולא נתנו להם להרים ראש ולהראות פעלם והדרם. מפני הרביים רפו ידי הרבנים ולא יכלו לעשות תושיה; ואמת נתנה להגיד, כי לא את הרבי היו יראים לעשות דבר, אך מפני בני הרבי וחתניו, והגבורים שומרי משמרת החצר, השוקלים ומודדים את המעשים והפעולות, אם הם מתאימים עם שיטתם ומטרתם הם, והם אשר נתנו חתיתם על הרבנים ומוראם עליהם, כי כל דבר לא יבצר מהם לכבוד שמים, היינו לכבודם ולכבוד בית אביהם. ומי יקשה אליהם וישלם? והרבנים שפטו, כי אם יפרוץ סכסוך בינם לבין חצר הרבי, אז אף אם לא יהי הנצחון על צד השני, ולא ידיחום משאתם, אבל – הלא תהי מריבה בישראל, וגדול השלום.

Among the ideas of new Masoret ve-Herut organization Graubart helped organize was to open new schools (gymnasiums) where all the Jewish studies would be taught in Hebrew, and also to teach secular studies. Graubart tells us that the Lubavitcher Rebbe, R. Shalom Dov Ber Schneersohn, was opposed. This aroused the anger of R. Itzele who declared that anyone who opposes the approach of Masoret ve-Herut is destroying the nation. Graubart then tells us about his own dealings with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, and reveals a little known historical fact that certainly will never appear in any Lubavitch historical literature (120-121):

הגדתי לו, כי אחשוב שאינו יודע כי רוב אנשי חסידיו, היושבים בערים הגדולות, שולחים את בניהם ובנותיהם לבתי ספר העמים ומחללים שבת. וכאשר שאלני: “מנין אתה יודע, שאין אני יודע זאת?” עניתיו: “אם כן יגדל התמהון יותר; מדוע אתה מתנגד לגימנזיות עבריות, אשר תהיינה תחת השגחת חרדים?” ויחשה ולא ענה דבר.

The approach of the Rebbe is not surprising, and a similar thing occurred in Lithuania where, as R. Dessler explained, the rabbinic elite was prepared to see many “go off the derekh” rather than institute any changes in the “Torah-only” approach that dominated in yeshivot.[46]

Yet Graubart’s own approach is seen in the following, which shows his more enlightened Orthodox perspective (98):

התורה קוראת תגר: למה כל הרופאים והסוללים [47] היהודים אינם שומרי דת? בשום אופן אין אנו מודים, כי מי שהוא מתפלל ומניח תפילין, אי אפשר לו להיות רופא אמן, וכי המדקדק בשמירת שבת ובאכילת בשר כשר, לא יהיה למהנדס ותוכן; כל העבר שלנו מעיד נגד זה: רב סעדיה גאון, רמב”ם, רמב”ן, ר’ אברהם זכות, אברבנאל, ר’ יש”ר, ר’ מנשה בן ישראל, יתנו עדיהם כי לא בחלול שבת – פילוסופיה ותכונה – ולא באכילת טרפה – חכמה הרפואה.

His description (55) of his interaction with R. Joseph Rozin is also worth quoting, as it is line with so many other portrayals of the Rogochover, especially that of Rav Tzair in his Pirkei Hayyim.

הוא איש מופת יחיד בדור (וגם בדור ודור) יודע את כל תלמוד בבלי וירושלמי רש”י תוספות ורמב”ם בעל-פה. מן הראשונים הוא מחזיק לאוטוריטטים רק את רש”י ורמב”ם. הוא מכיר היטב את ערך עצמו ומבטל את גדולי הדור, מזכירם בשמם בלי תואר “רבי” ואיננו חושש להוציא עליהם משפט, שאינם יודעים את התורה כלל . . . הוא איש טוב ותמים כילד: שוקד על למודו תמיד; בהוויות עולם איננו בקי. חסידי לובוויץ מפרנסים אותו, ולא בהרחבה כראוי לשר התורה כמוהו, כי ראיתי כלי ביתו מעטים וקלי-ערך.

Notes

[1]Teshuvot Maharashdam, Orah Hayyim no. 37:

שחמשה או י’ אנשים חשובים עולים לאלף בין מצד החכמה ובין מצד העושר כי העושר קרוב למעלת החכמה . . . שמה שאמרו רוב הוא רוב טובי העיר בעלי כיסים הם מה שנקראים רוב אפי’ הם מיעוט בערך דלת העם מ”מ הם הנקראים רוב . . . והעיק’ לילך אחר רוב מנין כשיהיו רוב בנין דאז ודאי לא יבחרו אלא האמת והיושר משא”כ ברוב ההמון

[2] Note how de Medina is arguing from Aggadah to prove a halakhic point, a fact already discussed by Menachem Elon, “Modes of Halakhic Creativity in the Solution of Legal and Social Problems in the Jewish Community” (Hebrew), Yitzhak F. Baer Memorial Volume [= Zion 44] (1979): 259ff. Since Aggadic sources and darshanut can be easily manipulated to say what one wants, do we not really have here an early version of Daas Torah? The only real difference between the modern exponents of Daas Torah and the earlier ones seems to be that the earlier authorities felt the need to support their opinions, which they came to based on logic and intuition, with Scriptural and Aggadic proofs. The modern exponents often feel no need to offer any justification of their views.

[3] Translation in Menachem Elon, “On Power and Authority: The Halakhic Stance of the Traditional Community and Its Contemporary Implications,” in Daniel J. Elazar, ed., Kinship and Consent: The Jewish Political Tradition and Its Contemporary Uses (Washington, D.C., 1983), 309.

[4] Orah Hayyim, no. 20.

[5] R. Shabbetai Hayyim strongly supported de Medina’s approach. See Torat Hayyim, vol. 2, no. 40.

ופוק חזי בעירנו זאת שאלוניקי עיר ואם בישראל מימי קדם בימי איתני גאוני עולם, הממונים המפקחים על ענייני צבור הם העשירים מביני מדע בעצת החכמים השלמים, ואינם משגיחים על דברי רוב רובי דלת העם, והדעת נותן כן שהרי רוב ענייני הצבור הם בהוצאות ופרעונות ולראות ולדקדק להוציא בעת הצורך ובמקום הצורך שלא יצא הממון לאיבוד, ומי יחוש על זה לכוין ולדקדק חוץ מהם שמוציאים הממון.

Yet this opinion was not unanimous, and the poor found at least one defender in R. Isaac Adarbi, de Medina’s Salonikan colleague. According to Adarbi, only in matters concerning outlay of money do the wealthy have authority. In other matters there is no such discrimination. In line with this understanding, he comes to the defense of a community that ousted its parnasim who were ruling in a dictatorial fashion and not responding to the needs of the poor. See Divrei Rivot, Yoreh Deah, no. 224.

[6] See Zikhron Yaakov, vol. 2, p. 196:

אני קורא מגילת איכה, חורבן בית המקדש, אינקוויזיציות ופוגרומים, משא נמירוב, כל הצרות והפגעים שעמדנו בהם כאין נחשבו נגד גזרת הקנטאָניסטין

[7] See Zikhron Yaakov, vol. 1, 122f

[8] R. Barukh Epstein describes how his grandfather stood up to the

chappers. See

Mekor Barukh, vol. 2, 964ff. I see no reason to doubt the general thrust of his story, although, as is often the case with regard to Esptein, fictional details have no doubt been added to create a better story. Hayyim Karlinsky,

Ha-Rishon le-Shoshelet Brisk (Jerusalem, 2004), 214ff., has a long description of how R. Joseph Baer Soloveitchik (the

Beit ha-Levi) also stood up to the communal leaders and demanded to know why only the poor kids should be taken. Regarding the future Torah scholars, see

ibid., 217: תועבה נעשתה בעיר סלוצק למסור לעבודת הצבא בן-תורה שעתיד להיות גדול בישראל. As with

Mekor Barukh, I see no reason to doubt the basic story Karlinsky presents, but this book – which the author tells us in the preface took him over forty years to write – also has all sorts of fictional details added for literary purposes. One might even say that Epstein, Karlinsky and Judah Leib Maimon, the author of

Sarei ha-Meah, are midrashic writers, in that they take a story and elaborate on it, thus creating a nice tale that keeps the reader’s interest. While the original story would leave many things unexplained, the midrashic “historian” provides the answers. For Yehoshua Mondshine’s attack on Karlinsky’s reliability, see

here.

In “Polmos ‘ha-Rabbanim ve-ha-Shohetim’ be-Harkov,” Zekhor le-Avraham (1999), 383 n. 10, Mondshine writes the following about Karlinsky’s book:

מבחינת ערכו לתיאור ההיסטוריה, משתווה ספר זה לספרים “מקור ברוך” ו”שרי המאה”, שכל דמיון בין המתואר בהם לבין המציאות הוא מקרי בהחלט.

[9] Larry Domnitch, The Cantonists: The Jewish Childrens’ Army of the Tsar (Jerusalem, 2003), 70.

[10] Ibid., p. 127.

[11] Tsar Nicholas I and the Jews. The Transformation of Jewish Society in Russia 1825-1855 (Philadelphia, 1983), 29.

[12] Ibid., p. 33.

[13] See Malkah Peles (Maisler) Va-Yehi ([Haifa], 1988). I thank Dr. Amihai Mazar for sending me the relevant pages from this privately printed volume. Weinberg was a cousin of the Mazar (Maisler) family (famous for its archaeologists).

[14] See my Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy: The Life and Works of Rabbi Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, 1884-1966 (London, 1999), 4.

[15] Ha-Peles 2 (1902): 49ff.

[16] R. Samuel Landau and the Hatam Sofer opposed this approach and believed that that all should be included in the lottery when the community was required to meet a draft quota. (The one exception to this statement is that the Hatam Sofer states that Torah students must be exempted.) See Judith Bleich, “Military Service: Ambivalence and Contradictions,” in Lawrence Schiffman and Joel Wolowelsky, eds., War and Peace in the Jewish Tradition (New York, 2007), 423 (called to my attention by Menachem Butler).

[17] Israel Zinberg, A History of Jewish Literature, vol. 6, pp. 218-219.

[20] Im Hillufei Tekufot (Jerusalem, 1960), 225.

[21] Volumes 1 and 2 of this set have recently been reprinted. See

here.

[22] R. Isaac Bunin, Hegyonot Yitzhak (New York, 1953), no. 2, has a fascinating responsum from 1908, when he was a rabbi in Russia. This was the era of anarchist communists terrorizing the population for “contributions” to the cause. It was this circle that gave us the slogan “From each according to his means, to each according to his needs.” One man decided to shoot the anarchists the next time they came to his town, and the question for Bunin was if he is also permitted to shoot them on Shabbat. The rabbi decided in the affirmative.

[23] Although he is entirely forgotten today, during his lifetime Burstein was regarded as one of the Torah world’s top scholars. Nathan Kamenetsky,

Making of a Godol: A Study of Episodes in the Lives of Great Torah Personalities (Jerusalem: Hamesorah Publishers, 2002), 400, quotes a source that “he was considered the third-greatest

rosh yeshiva of his time – after R. Hayyim Soloveitchik and R. Itzel Ponivezher.” When R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg was asked in 1925 about the problem of

Austritt, he recommended that his questioner turn to a few different East European

gedolim, one of whom was Burstein. See

Kitvei ha-Gaon Rabbi Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, vol. 2, 235 (In this letter, Weinberg states that R. Meir Simhah of Dvinsk is a גדול-הדור באמת.) Towards the end of his life, Burstein went on aliyah and taught at Merkaz ha-Rav. His

Ner Aharon is currently sold by the yeshiva. See

here. Burstein’s son was Reuven Barkat, an important Labor party figure in Israel who also served as speaker of the Knesset. See

here

[24] Sefer Zikaron (Lodz, 1926), 107.

[25] See R. Avraham Shapira, Morashah (Jerusalem, 2005), 15.

[26] Mark writes . לר’ איצל היה צער גידול בנים ולא שבע נחת מבניו This is a polite way of saying that his sons did not remain Orthodox, which was a very common phenomenon in those days.

[27] Mark, Bi-Mehitzatam, 118, claims that R. Itzele concluded his speech at the Moscow gathering by stating that the government should only be able to remove property from landowners if payment was made, but this is not what appears in Graubart’s record of his speech and I don’t believe it is correct.

[28] R. Joseph Elijah Henkin used this logic in his defense of rent control laws, which are a terrible intrusion into the rights that a landlord has over his private property. R. Henkin wrote as follows, unfortunately falling into some Democratic class warfare rhetoric (Kitvei ha-Gaon R. Yosef Eliyahu Henkin, vol. 2 [New York, 1980], 175):

חוק הדירות של הממשלה הוא ישר, מתוקן ומקובל בפרט בערים הגדולות, כי הוא מכוון נגד מפקיעי שערים ופושטי עורות עניים. ואף שלפעמים נראה כעול נגד בעלי בתים שאינם עשירים, הנה כן דרך החוק שלפעמים נפגע ביושר ואזלינן בתר רובא. ומה שהחק מפלה בין דירות עניים לבתי לוקסוס אינו מגרע כח החק אלא מעדיפו ומטהו אל צד היושר, וכן מה שהחק משתנה מזמן לזמן.

For a recent attempt by rabbis to enforce a rent control scheme, see

here,

here, and

here. There is an inverse proportion between these rabbis’ talmudic knowledge and their knowledge of economics and what drives markets.

[29] Jody Myers has recently published an entire book about the Kabbalah Centre. See Kabbalah and the Spritual Quest: The Kabbalah Centrein America (Westport, 2007).

[30] See Jacob J. Schacter, “Reminiscences of Shlomo Barukh Rabinkow,” in Leo Jung, ed., Sages and Saints (Hoboken, 1987), 102, 106.

[31] There was one time, however, when he broke ranks with them and this created some controversy. When the divorce rates in the Orthodox world began to move up, R. Bick publicly declared that a few dates were not enough to determine that one had found one’s life partner and people should therefore should stop hurrying to get engaged but take more time to get to know each other better.

[32] Dan Rabinowitz, “Mayim Hayyim, the Baal Shem Tov, and R. Meir the son of R. Jacob Emden,”

the Seforim blog (January 29, 2008), available

here.

[34] “Glowing Embers: Maintaining Religious Life in the U.S.S.R.,” Tradition 24:1 (Fall 1988): 91-103.

[35] Bick and Zvi Harkavy, eds., Shomrei ha-Gahelet: Divrei Torah me-et Rabbanei Berit ha-Moatzot ve-Artzot ha-Demokratyah ha-Amamit (Jerusalem, 1966).

[36] Netser mi-Shorashav: Motsa’o ve-Olamo ha-Yehudi shel Karl Marx (Tel Aviv, 1984). See also his Me-Rosh Tzurim: Metaknei Hevrah al Toharat ha-Kodesh: Shalshelet ha-Yuhasin shel Avot ha-Socialism (Jerusalem, 1972), and “Between the Holy Ari and Karl Marx” (Hebrew), Hedim 110 (1980): 174–181. I don’t have access to the volume at present, but in Shvut 7 (1980), Bick also has an article on the Jewish roots of various communist figures.

[37]

Grunt-Printsipn fun Religyezn Sotsyalizm (New York, 1938),

Kemper un Hiter: Di Sotsyaletische Idee in der Yidisher religyezer Literatur un Lebn (New York, 1940).

[41] See here

[42] Iggerot R. Chaim Ozer, vol. 2, 69.

[43] See David Tidhar,Entziklopeyah la-Halutzei ha-Yishuv u-Vonav, 1875.

[44] Just glancing through the book, I also found a fascinating passage on p. 31. Here Glasner daringly suggests that the reason for keeping kabbalistic considerations out of halakhic decision-making – and he is referring specifically to a pesak of R. Hayyim Halberstam – is that it permits non-halakhic subjectivity to enter the halakhic process.

ומי שמכוון פסקיו לחכמת הקבלה, מי יודע איזה רעיון קדמה בזמן. ואם הוא מופשט מן החומר וקרוב לשמים ואדוק בעולמות העליונים קרוב לודאי שרואה תחילה בסוד אלקי, וממילא משוחד הוא לכוון ולהתאים הנגלה להאי סוד שראה. לכן לאו דסמיכנא הוא מהאי טעמא גופא.

For a discussion of R. Halberstam’s perspective on the role of Kabbalah on halakha, see Iris (Hoyzman) Brown, “Rabbi Hayyim Halberstam of Sanz: His Halakhic Ruling in View of His Intellectual World and the Challenges of His Time,” (PhD dissertation, Bar-Ilan University, 2004), 162-164 (chap. seven).

[45] See Martin Hengel, “The Interpenetration of Judaism and Hellenism in the pre-Maccabean Period,” in W. D. Davies and Louis Finkelstein, eds., Cambridge History of Judaism (Cambridge, 1989), 184. R. Aharon Lichtenstein commented that some people, upon learning of Socrates’ blessings and the corresponding Jewish blessings, will find that their attitudes towards the latter are “undermined.” He continues: “A different mentality could of course, as did Newman analogously, revel in the scope of its tradition’s prevalence – even if, as with respect to gender here, for radically different reasons – and not feel threatened at all.” See “Torah and General Culture: Confluence and Conflict,” in Jacob J. Schacter, ed., Judaism’s Encounter with Other Cultures: Rejection or Integration (Northvale, 1997), 278. I am certain that R. Lichtenstein knows that there are indeed voices in the “tradition” that approximate the common Greek view of women. R. Lichtenstein is in general opposed to positing outside influences on Hazal’s outlook. See, for example, the following (“Of Marriage, Relationship and Relations,” in Rikvah Blau, ed., Gender Relationships In Marriage and Out [New York, 2007], 23):

To be sure, post-Hazal gedolim, rishonim, or aharonim may be affected by the impact of contact with a general culture to which their predecessors had not been exposed and to whose contact and direction they respond. Upon critical evaluation of what they have encountered, they may incorporate what they find consonant with tradition and reject what is not. In the process, they may legitimately enlarge the bounds of their hashkafa and introduce hitherto unperceived insights and interpretations.

Note how outside influence upon Jewish thought is limited to the post-Hazal era. While this may be good theology, and in some circles is even viewed as obligatory, it is certainly bad history. To mention only one example, Yaakov Elman’s groundbreaking work is revealing all sorts of influences that provide us with a completely new picture of talmudic law and thought. See Yaakov Elman, “The Babylonian Talmud in Its Historical Context,” in Sharon The Talmud in Translation” in Sharon L. Mintz & Gabriel M. Goldstein, eds.,

Printing the Talmud: From Bomberg to Schottenstein (New York: Yeshiva University Museum, 2005), 19-27; now available online

here.

[46] Mikhtav me-Eliyahu, vol. 3 (Jerusalem, 1963), 355ff.

[47] I have no idea what this word means, but it clearly refers to some white-collar profession.