Review of Amudim be-Toldot Sefer ha-I…

Yaakov S. Spiegel, Amudim be-Tolodot Sefer ha-Ivri Haghot u-Maghim (Chapters in the History of the Jewish Book Scholars and their Annotations), Ramat Gan, 20052, 689 pp.

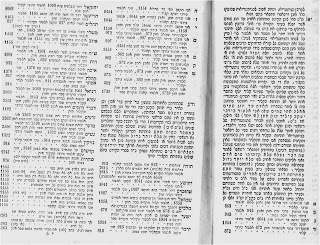

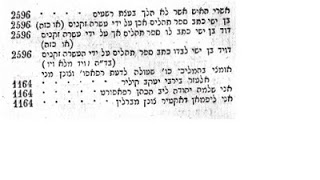

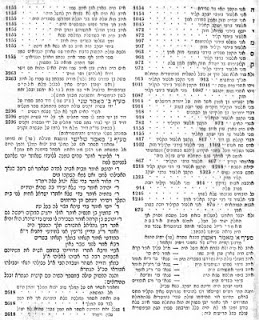

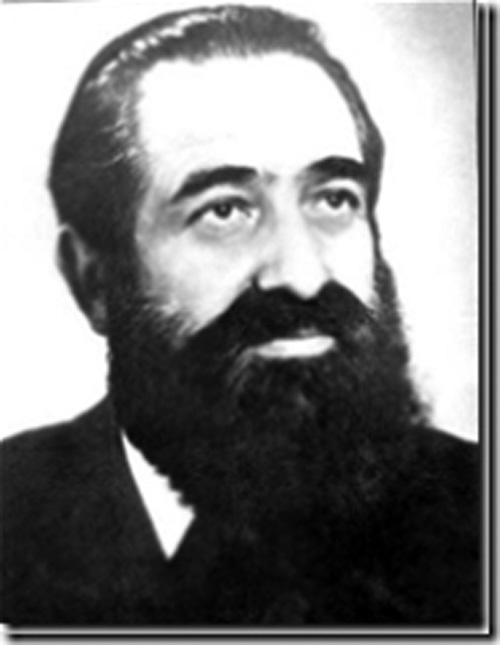

In 1996, Bar Ilan Press published Amudim be-Toldot Sefer ha-Ivri Haghot u-Maghim from Professor Yaakov S. Spiegel. Shortly thereafter, this edition sold out due to its popularity. A few years later Amudim be-Toldot Sefer ha-Ivri Kitevah ve-haTakah (volume two) was published. More recently, Amudim be-Toldot Sefer ha-Ivri Haghot u-Maghim was reprinted with over seventy five pages additional pages full of many important additions. In this new edition, Spiegel apologizes to the people who purchased the first edition of his work and would now have to buy the new one if they want the updates. Spiegel offered that the requirement for a completely new edition rather than an addendum was out of his control. Although the importance and quality of the book will be obvious shortly, it has not been reviewed or discussed properly in academic journals except for a short review on Hamayan (37, 3: 69-75). This post hopefully is a start in rectifying this omission. This volume is the first of two (current) volumes discussing the History of the Jewish book – specifically the creation and alteration of the Jewish books. That is, this volume covers annotating or editing texts. Essentially, this work is divided into two parts, (Spiegel divides it into four parts) the first, discusses the permissibility of editing texts and the second discusses annotators and editors. The first portion begins with the sugyah of editing texts in the time of the Mishana (sifrei torah) and moves into the topic of the prohibition of having a unedited sefer. These two chapters play an important role in the background of this topic of editing seforim. Spiegel then moves into the era of the geonim and rishonim dealing at great length with there methods of editing or annotating texts. He discuses at great length the methods of Rabbenu Gershom, Rashi and Rabbenu Tam. As is well known Rabbenu Tam prohibited the editing or annotating texts Spiegel discusses the complete background of Rabbenu Tam's opinion going through the myriad of sources when Rabbenu Tam's restriction applies. This discussion includes an analysis of Rabbenu Tam's work Sefer Hayashar and his famous disagreement with R Meshulem. Spiegel, as he does in each of the chapter, quotes all the previous sources on the topics and rechecks it all carefully and comes out with many new important conclusions. Spiegel then proceeds to deal with the different works of haghot in the times of rishonim and the nature of these works. Of particular interest is his sections on the Haghot Ashrei (pp. 183-90) and on the Ravad's comments on the Ramabam discussing if those comments are plain haghot or hasaghot (pp. 198-207). The second section of the book surveys the story of Haghot u-Maghim from the beginning of the printing press, in approximately 1456, until 1840. He begins with chapters on the importance of the printing press (see also pp. 300-06) and moves in to the job of the annotators and editors and their methods. Dealing with topics such as, did Rabbenu Tam only speak to instances where one is erasing the text and substituting another but if one merely notes an alternative reading and preserves the original that is OK? Or, is it only applicable to manuscripts or does it apply to printed works as well? The distinction being, in the case of a manuscript, that manuscript may be the only copy and, if one alters the text, the original is forever lost. Additionally, Spiegel discusses at length the important question of whether one can correct texts based on logic or textual support. An interesting section is where he brings a bunch of sources that there is a special will from God that these mistakes happened and should remain (pg 262-269). There are chapters on the various 'editors' such as R. Betzalel Ashkenazi, R. Yoel Sirkes (Bach), Maharshal, Maharsha, Maharam, R. Jacob Emden, R. Y. Pick, Gra, Rashash, and a host of others. For each one Spiegel discusses which version of the Talmud they were addressing their emendation and whether their emendations were based on manuscript evidence or their own determination that the text was corrupted. These questions are very important. For example, Spiegel notes that the Maharshal (p. 315) and Maharsha (p. 323) did use manuscript evidence many times whereas the Maharam (p. 325) did not use manuscript evidence frequently. As to the Bach's emendations, Spiegel notes that weren't published until the 19th century, but the Bach's comments were addressed at earlier, different version of the Talmud. Thus, at times, it is unclear what the Bach is changing. Indeed, Spiegel shows how some commentaries have misunderstood the Bach's comments. Spiegel deals with at length what the Bach's goals were. Spiegel also shows that there were additions to the work after the Bach's death. As to the Bach's usage of manuscripts Spiegel shows it's still not proven that the Bach used them as most of the changes can be found in Ein Yakkov. Spiegel devotes a long chapter dealing with the Gra notes amongst the topics he discusses are what was the Gra's point in his comments, and to why there are contradictions in his notes on Shas to his other writings (pg 450). As to the question of whether the Gra used manuscripts Spiegel concludes that it appears that he did not [although he did visit libraries and saw old seforim (pg 454-457)]. Another whole section Spiegel devotes to is discussing Rabinowich's Dikdukei Soferim at length. This is especially important in that Dikdukei Soferim is a collection of variant readings of the Talmud. As many great Rabbis of Rabinowich's time praised this work, this tends to show these Rabbis' position on emending texts. Spiegel shows the may people who used it and how those who did not use it could have benefited from availing themselves to Dikdukei Soferim. Spiegel deals with various theories why it was not used widely. He concludes that it appears that the Dikdukei Soferim is becoming more widespread. He even quotes recent sales of Dikdukei Soferim and notes how quick it sold out after being reprinted after being out of print for quite a while. Although a Otzar haChochma search comes up with well over 2000 hits in over a thousand seforim (of course not all this are good hits as there search engine is still limited although useful). It still does not appear that the Dikdukei Soferim is used widely in the main yeshiva circles. Perhaps that will change.

Spiegel deals extensively with the position of the Hazon Ish regarding manuscripts. This topic, one which has gotten much attention (see, e.g. the Shnayer Z. Leiman, Kook, Moshe A. Bleich articles in Tradition, Hevlin in Meah Shearim as well as the articles in Beis HaVaad), is discussed in detail with the backdrop of all the nuances Spiegel raises throughout this work. Spiegel discusses the curious fact that the Chazon Ish himself did sometimes use the manuscripts of Gemarah when learning (p. 567 n.126). Spiegel concludes this section with a discussion on to more recent printings of the Shas such as the shas Vilna, Frankel and Oz veHadar. It appears that the methodology of both Shas Vilna (the original one) and Oz veHadar in deciding which texts to use etc are not clear. This is especial important to know with Oz veHadar what the methods that they use as they advertise as if they are making incredible important changes but one only wonders what they are ad on what basis they are made. The last section of the sefer is devoted to the various annotators and editors to various editions of the Ramabam including the editions of Bragadin and Justintine. Spiegel also deals with when were the divisions of halachot put into the Rambam (pp. 637-638). He also deals at length with the Amsterdam edition and the comments of R. Sholom Leon and showing its influence on later editions. R. Sholom Leon authored other seforim including Mesectas halacha Le moshe miSinia which was recently printed in a annotated edition including a nice introduction. The editor of this new edition was not aware of Spiegel discussion regarding R. Leon. Spiegel has an interesting discussion about a third work called Merkevet ha-Mishna by R. Leon that was not known to many people and thus people made a mistake attributing a source (pp. 648-49). It is amazing to see Spiegel's mastery of the Talmud and the sources with all its nuances throughout the book. The amount of classical seforim quoted and discussed is breathtaking many very rare works are quoted. Another point is the respect and tone he uses when he speaks about all the authors, a problem some have with many academic books. Another thing is he is not embarrassed to admit mistakes he made – he could have easily left out a specific footnote instead he writes it and explains that he made a mistake (see, e.g., p. 259). From the above, it should be apparent that this book contains a wealth of information regarding the issue at hand, emending texts. While that alone would be enough to recommend in the strongest terms this book, it must be noted that Spiegel, mainly in the many footnotes, covers an amazing amount of tangential topics. Here are some examples:p.29 n. 8 Spiegel has a discussion about the sefer Kol Dodi quoted by Agnon (for more on this work see this post ).p. 41 n.12 sources regarding the custom of placing a possul sefer torah in the ark and whether this violates the prohibition of "al tiskon be-ohelkha" (one should not have uncorrected texts in their home).

p. 65 n.105 testimony from R. Yaakov Katz that Rav Hai Goan was a copyist.

p. 75 n.153 noting that la"z the term used to indicate a translation should not contain the quote mark as it is not an abbreviation.

p. 80 n.177 noting that Krochmel in his Moreh Nevukeh haZeman quotes the Mahritz Heyos only as "Hakham Eched."

p. 89 n.29 discusses R. Zevin's offhanded comment that the rishonim did not use "nusach aher."

p. 102 n.110 discusses "nusach Sefard" and whether it is more reliable.

p. 103 n.115 notes that although a statement from the Rosh (responsa, klal 20, no. 20) is used by multiple authors to show that Ashkenazik customs have a long history, those many authors ignored the other implication of the statement regarding the "nusach haTalmud shel beni Ashkenaz."

p. 105 n.123 who authored rashi on Horyois.p.105 n. 126 if one learnsa small daf is it considered a Complete daf.p.107 n.132 discussing the issue of when the Talmud records a pusuk differently than our Sifrei Torah. p. 131 n.14 corrections of rashi that were later added into the printed edition of Shas.p. 142 n.55 when Rashi says Hachei Garseninon did he have a different version in front of him.

p. 170 n.64 the common meaning of the word "sefer" – as in yodeah sefer which sefer?

p. 218 n.7 Spiegel explains the melitza used by the printers of the 1494 Nevim to describe what they did. The melitza includes the line "lower the high and raise the lower" (Ezekiel 21:31). Dr. M. Glaser explained that in the early printing presses the letters would be set and they faced upwards, the printer would coat them in ink and then place the paper on top. This is in contrast to how writing was done previously – from above.

p. 230 n.67 citing examples of books where the Soncino press accused the Bomberg press of using (illegally?) Soncino editions.

p. 234 n.79 discussing the alleged apostasy of Yakkov ben Hayyim Ibn Adoniyahu, the editor of the Mikrot Gedolot and other seminal texts.

p. 268 n.95 many sources that say the Havah Minah of the gemarah is true and important. p. 318 -21 he discusses the methods of R Dovid Meubin a talmid of the Maharshal in annotating the Gemarah including many general rules that he mentions in his sefer.p. 329 -35 discuses the notes of the Levush on shas if they were really from him and dealing with R. Zechariah criticism on this.p. 426 n.18 discuses about Fogelman work on R. Menasha Milyah.p. 464 n.167 the Gra's opinion on the laining on Rosh Chodesh.p. 540 n.29 the plagiarism of the Tolodos Adam.p. 587 n.41 deals with a bit if Chaim Bloch was a forger.p. 652 n.185 Kapach opinon on the Teshuvos of Rambam to Chachemei Lunel. In the academic world Spiegel work has gotten some attention for his discussion of the Chazon Ish and manuscripts. Specifically, Benny Brown in his unpulished dissertation, The Hazon Ish Halakhic Philosophy, Theology and Social Policy As Expressed in His Prominent Later Rulings (Hebrew) pp. 129-40, & Appendix pg 111- 113 deals with Spiegel's discussions with comments and additions. As has been noted here Sperber in his recent work Nesivos Pesikah uses Spiegel's discussions on this topic. And, in his doctorate on R. Betzalel Askenazi B. Toledano uses Spiegel's comments on R. Betzalel. Finally, others have used Spiegel's work, but as Spiegel notes only sometimes do they give Spiegel credit, (see here for more and see the introduction p. 13 and the notes therein and page 183 n.132). Finally, although Spiegel's work is very comprehensive, there are some additions to some of the topics discussed in the sefer: In the beginning of the book Spiegel has a chapter about אין כותבין ספרים תפלין ומזוזות במועד ואין מגיהין אות אחת אפילו בספר העזרה בספרים אחרים גורסים ספר עזראTo add to his long list of sources see Archaei Tanamim Vamorim (Rebbe of Rokeach) (Blau edition 2:666-67) and R. Meshulam Roth, Shut Kol Mevaser 2:2823. For the chapter (pp. 39-83) about המחזיק בספר מוטעה אל תשכן באהליך עולה see Efodi in his Maseh Efodie p. 18 in the introduction. For his chapter about Rabbenu Tam's methods of amending texts see also R. Yakov Shor (intro to Sefer haIttim p. vii) where he says he followed Rabbenu Tam's method in his edition of the Sefer haIttim and did make corrections on the actual text. In chapter twelve where he discusses the Mesectos which are not learned (407-414) Spiegel mentions Nedarim as not being learnt (p. 407). See also the Merei in his Seder Hakabbalah (p. 128 Ofek Edition) where he writes דעו בעדות נאמנה שלא נשנית מסכת נדרים בישיבה זה ק' שנהOn Nedarim see also R. Reven Margolis, Mekharim beDarkei HaTalmud, pp. 81-84; R. Zevin, Sofrim Veseforim (geonim) pp. 46-48; the extensive discussion of R. Zev Rabanovitz in his Shaerei Toras Bavel (pp. 299-310). About Meschates Moed Koton see the important comment of R. Yissacar Tamar, Alei Tamar Moed Koton pg 312; and Yeshurun 20:702. Another mesectah not really learnt in the time of the Rishonim was Mesectas Avodah Zarah see; Professor Chaim Solovetick, Hayayin Byemei Habenyaim pp. 133-36. When discussing Meshtas Chagigah (pg 409) he brings the famous story from the Menorot haMeor that:מעשה בתלמיד אחד, שהיה מתייחד במקום אחד, והיה למד בו מסכת חגיגה. והיה מהדר ומהפך בה כמה פעמים, עד שלמד אותה היטב והיתה שגורה בפיו, ולא היה יודע מסכתא אחרת מן התלמוד זולתה, והיה שונה בה כל ימיו. כיון שנפטר מן העולם הזה, היה לבדו באותו בית שהיה לומד בו מסכת חגיגה, ולא היה שום אדם יודע פטירתו. מיד באה אשה אחת, ועמדה עליו, והרימה קולה בבכי ובמספד, ותרבה אנחתה וצעקתה, כאשה שהיא סופדת על בעלה, עד אשר נקבצו ההמון, ואמרה להם, ספדו לחסיד זה, וקברוהו בכבוד גדול, וכבדו את ארונו, ותזכו לחיי העולם הבא, שזה כבדני כל ימיו ולא הייתי עזובה ולא שכוחה בימיו. מיד נתקבצו כל הנשים וישבו עמה סביב למטתו ועשו עליו מספד גדול, והאנשים נתעסקו בתכריכיו ובכל צרכי קבורתו, וקברו אותו בכבוד גדול. ואותה אשה בוכה במר נפש וצועקת. אמרו לה, מה שמך. אמרה להם, חגיגה שמי. וכיון שנקבר אותו חסיד נעלמה מן העין אותה אשה. מיד ידעו שמסכת חגיגה היתה, שנראית להם בצורת אשה, ובאה בשעת פטירתו לספוד לו ולבכותו ולקברו בכבוד, מפני שהיה שונה בה ושוקד עליה ללמוד אותה. והלא דברים קל וחומר, ומה חסיד זה שלא למד אלא מסכתא אחת בלבד כך, הלמד תורה הרבה ותלמוד הרבה ומעמיד תלמידים הרבה על אחת כמה וכמה. It should be noted that there are eleven versions of the story see S. Askenazi notes to Kav Hayashar and updated to 15 versions in his Alpha Beta Kadmita Deshmuel Zeria pp. 331-36. [These sources were not know to Y. Hacohen in his new annotated edition of the Magid Mesharim (p. 292). The Otzar Yad Chaim (pg 198) goes so far as to say that because of this story some say it's a segulah to learn this Mesechtah on a yarzheit. [See also Megedaim Chadashim introduction to Chaggiah.] In regard to The famous abrevation ענ"י which Mescetas were hard add R. Emden who writes on the Zohar which says עני איהו תמן בסימן עירובין נדה יבמות "בנה סוד על הלצה בעלמא, שהיתה מצויה בפי עוסקי התלמוד בישיבה, שלא יכלו לירד לעמקן של מסכתות הללו החמורות מאד, מחמת ריבוי החלוקות החדודות שבהן, הודו ולא בושו בעניות דעתם וקוצר יד השגתם, שלא יכלו להשוות כל הסוגיות השונות והסתירות הנמצאות בהן, לתרצם וליישבם כדרך שעשו בשאר כל המסכתות, חוץ מאלו קשות ולא מצאו כל אנשי חיל ידיהם. ונתנו בהן סימן על דרך הצחות, שלא יתפלא אדם, גם אם יאמר החכם למצוא פשר דבר לא יוכל, שכבר צווחו בהן קמאי דקמאי ולא אסקו בידייהו, אלא כמאן דמסיק תעלא מבי כרבא ועניא דקרי אבבא, היאומן שדברים כאלה יצא מפי תנא, אין צריך לומר מפי משה רבנו וא משאר נשמות מעולם הנעלם". (מטפחת ספרים עמ' מו). See also S. Askenazi, Alpha Beta Kadmita Deshmuel Zeria pp. 422-24. For General sources on this topic of which Mesctas were learnt (partially based on Spiegel) see M. Breuer, Ohelehi Torah, pp. 90-94. On page 280 Spiegel discusses the famous correction of a godal that the beracha of Pidyon Haben is אשר קרש עובר and not אשר קדש he brings some attribute it to R. Chaim Berlin. In the Zecher Daver, the Aderes has a fascinating chapter showing fifty seven examples how a kutzo shel yud makes a difference. The Aderes cites his friend, R. Chaim Berlin, who told him this (p. 20). On this see also R. Chanoach Erentru in his Eiyunim Bdevrei Chazal Vleshonoim pp. 144-45; R. Yissacar Tamar, Alei Tamar Shekalim (p. 17) writes he does not believe it's a mistake.Additionally, although Spiegel cites to one of Prins' books discussing this issue, פרנס לדורו p. 460 a discussion regarding this topic appears on page 455 of the same book as well as the other book from Prins, פרנס לדורות on page 270. On pp. 287-88 Spiegel discusses the Tana De be Eliyeahu with the perish Zikukin Denoroah Ubiyorin. But, see the strong words of the Radal against this pirish in his intro to Pirkei de Reb Eliezer p. 11 saying how this is what the Cherem against changing texts was referring to. See also A. Epstein (Kesavim vol 2, pp. 368-69); M. Ish Sholom, intro to his edition of Tana De be Eliyhu (pp. 4-7). Although Spiegel writes at the outset of his list of those who used Dikdukei Soferim that its not complete – the following can be added: R Sholom Albeck in his incredible sefer, Mishpachet Sofrim where he used the Dikdukei Soferim on almost every page (this sefer has a very warm haskamahs from the Maharsham and R Eleyahu Meisles amongst others). Another work well worth mentioning is the Shaerei Toras Bavel from R Zev Rabanovitz he also used Dikdukei Soferim extensively [in his work on Yerushalmi he also amends texts – but according to R Zevin in Sofrim Vseforim a bit to much]. Another person who used the Dikdukei Soferim was R. Greubart in Chavalim Beniymim (last page of volume 3, he also mentions seeing a shas from 600 hundred years ago in Chicago). Another person who used it was R. Yeruchem Leiner in his Tifres Yeruchem (pp. 115, 189). Another is R. Elyashiv in his teshuvot (1: p. 478) and in his work on Sotah he uses the Munich ed. in the Talmud HaYisraeli edition (p. 234). A Bar Ilan search shows that others not included in Spiegel list use or used it such as Beis Mordechaei and Shevet haLevei (four times), the latter being very interesting as he is close to the camp of Chazon Ishnicks. Bar Ilan search also shows that some of the Gedolim which Spiegel shows used it used it even more than he shows such as R Zodok and the Or Someach. In Spiegel's discussion of the Adres using Dikdukei Soferim Spiegel does not have too many sources (p. 491). To add to this: first in Knesses haGedolaih the Adres uses it in at least two places – these two pieces are now printed in back of his Har haMorieah printed by Ahavat Sholom pp. 253 and 254. In his sefer Megilat Simanim which explains all the Simanim in Shas he used the Dikdukei Soferim numerous times (see index) this work was printed after Spiegel printed his sefer. In his Tefilah leDovid (Ahavat Sholom edtion pp. 8-9,23, 25, 121, 125, 137) (which is the best edition of thos work) we see he was involved in switching texts some times based on manuscripts of Rishonim. On page 500 Spiegel leaves one thinking that A. Epstein was not pro the Dikdukei Soferim, which is not true at all (see Epstein's Kesavim vol 2 p. 354) where he criticizes Halevei for בכל ספרו לא נמצא זכר החיבור הנחמד דקדוקי סופרים, שנאספו ובאו בו נוסחאות כתבי יד שונים וספרים עתיקים. (see also pgs 83,51,357). Another very interesting passage in regarding Dikdukei Soferim was written by A. Berliner:בדרכי לברלין השתמשתי בשעת הכושר לבקר במינכן את ידידי המלומד רבינוביץ ולהציץ למעבדתו הרחונית בה נעשית היצירה הגדולה דקדוקי סופרים שהכרך הששי מאותו הספר הענקי יצא בזמן האחרון. כאן השתוממתי והתפעלתי מאוסף כתבי היד ודפוסים יקרי המציאות, המשמשים יסוד לרבינוביץ בעבודתו. ובאמת ניתן לומר, שאותו מפעל גדול ונהדר, להוציא את התלמוד הוצאת ביקורתית על יסוד כתבי היד ואינקונאבלים הוא מפעל לאומי, הראוי לתמיכה מצד כל אלה, שיש להם הבנה למדעי היהדות ולב פתוח ועד לקידומם. איני יודע חתימה נאה לפרשת מסעי מאשר להביע את משאלתי מי יתן ואותו מפעל גדול יוכתר בהשלמה וסיום מוצלחים". (ששה חדשים באיטליה עמ' עב). On page 426 Spiegel deal with the reliability of M. Fogelman (Plungin) see the interesting piece by A. Korman in Musagim Behalcha p. 203. See also the recent article from D. Kamentsky in Yeshurun vol 20. On pages 428-29 Spiegel deals a little with the Kol Hatohar. It should be added the recently printed work Olam Nistar Bemaddei Hazman by R.Shucat pp. 262-91 (see also this post discussing Shucat's work generally.) To the disscusion of Chazon Ish and manuscripts see also Maseh ish 1:93; 2:72, 218; 3:92 Finally to add to Spiegel's sources on pages 555, 569 regarding the yarhzeit of Yehoshua bin Nun. R. Hamburger, in his Shorshei Minhag Ashkenaz (3:262) points to one such source that Lag b'omer is the yarzeit. Additionally, in the Megillas Ta'anis, the last section, there's a section called Megilas Taanis Basra. In many versions of this text, the death of R' Yehoshua bin Nun is on Lag b'omer. Professor Shulamis Elitzur, in a recent incredible book, Lama Tzamnu, deals with this at great length and brings many early sources from ancient piyutim which verify this (pp. 18, 26, 34, 39, 66, 120, 126, 172).