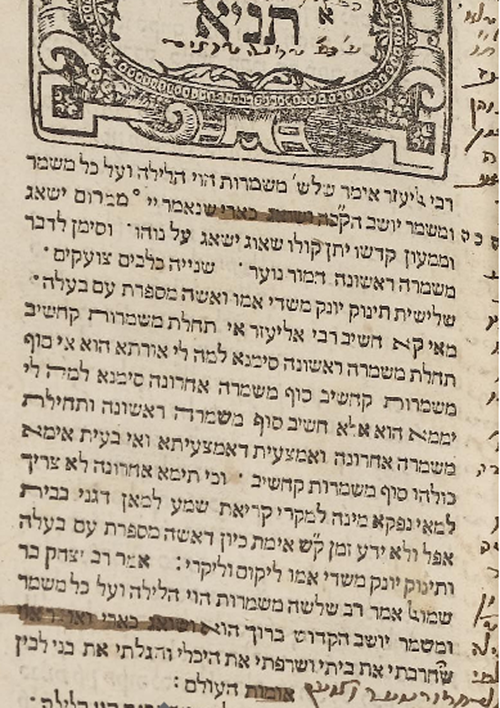

Preview of R. Shmuel Ashkenazi’s Latest Work

One of the hidden giants of the seforim world both in ultra orthodox and academic circles is a man known as Rabbi Shmuel Askenazi. Professor Zev Gris writes about him:

אני ובני דורי נוכל להעיד על בור סיד שאין מחשב שידמה לו, כר’ שמואל אשכנזי גמלאי מפעל הביבליוגרפיה העברית”) הספר כסוכן תרבות מראשית הדפוס עד לעת החדשה, לימוד ודעת במחשבה יהודית (תשסו) עמ’ 257).

This man has authored many books and hundreds of articles in dozens of journals – both academic and charedi. Besides for authoring so much he has assisted many people in both circles helping in many areas of the Jewish literature. At times he is acknowledge and thanked and other times not. A few years back, a partial bibliography of his writings was printed in a work called Alfa Beta Kadmita de-Shmuel Zera. This book was a start of an attempt to print all of his writings in a multi-volume set. R. Askenazi has been writing and collection information on thousands of topics for close to seventy years. Unfortunately, he did not print much of what he gathered. The main reason for this omission is R. Ashkenzi’s “weakness” for incredible levels of perfection. When he printed his Alfa Beta Kadmita de-Shmuel Zera he proofread it seven times (the work is over 800 pages!). [If the editors of this blog attempted to emulate that level of perfection, there would be, perhaps, one post a year.] Now to understand the significance of this one has to know that one of his many specialties is his incredible ability to find mistakes in grammar, typos and the like – a master proofreader. It is as if he has like a homing device built in as soon as he sees the printed text he notices the mistakes. Now after his sefer went to press he still found mistakes and it disturbed him greatly. He learned from this an important lesson which he already knew.

לא עליך המלאכה לגמור

For personal reasons the project that began a few years back was stopped by R. Askenazi. Two years ago the project was restarted again by others. He and these people have been working daily to prepare the writing for print. To date this project has gotten very far in preparing for print his writings. Two volumes of over five hundred pages are ready to go, a few more are almost near completion. The only thing holding back the printing is funds to print the volumes. No one is making money off the project the hope is that if enough funds to cover the printing of the first few are raised than the sales will hopefully be enough to cover the printing of the rest. We are talking about multiple volumes as this is one man’s writings of over seventy years. Not everything that he gathered is worth printing and heavy editing is done as with many of the available data bases what he gathered today is not worth much as a quick search on these data bases will find the same thing. The topics that these works deal with are virtually everything on some level, sources on expressions, minhaghim, dininm, evolvement of famous stories, bibliography corrections of authors encyclopedia style information on thousands of topics culled from thousands of seforim many very rare or unknown. There are also thousands of letters to authors and professor’s containing notes on their works additional sources of their work etc; In addition there are R. Askenazei notes on tefilah, piyut, Chumash, Shas, Zohar, and from other seforim that he marked down on the side. It is a work that almost anyone interested in the Jewish book will find many things to enjoy. I hope that you can help contribute I know very well that the financial times are very hard but even a little bit can assist this project move forward. For more information please e mail me at eliezerbrodt-at-gmail.com. We are printing here for the first time, a chapter from one of the books which is print ready.

כי הוו חלשי רבנן מגרסיהו, הוו אמרי מִלתא דבדיחותא

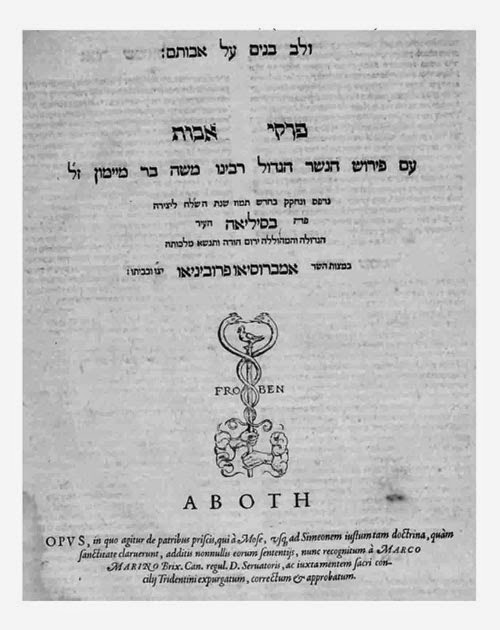

כתב ר’

משה בר’ מימון [הרמב”ם; ד’תתצח-תתקסה]: כמו שילאה

הגוף בעשותו המלאכות הכבדות עד שינוח וינפש, ואז ישוב למזגו השוה – כן צריכה

הנפש גם כן להתעסק במנוחת החושים, בעיון לפיתוחים ולענינים הנאים, עד שתסור ממנה הַלֵּאוּת.

כמו שאמרו. כי הוו חלשי רבנן מגרסיהו, הוו אמרי מלתא דבדיחותא (שמונה פרקים, פרק ה, בהוצאת ‘ראשונים’, תל-אביב תשח, ס”ע קפד – ר”ע קפה).

וכבר נלאו חכמי לבב למצוא את מקור המאמר שהביא הרמב”ם

[1]. ויש מי ששִׁער, שהיתה לפניו גרסא שונה בתלמוד הבבלי. כן כותב ר’

שאול ליברמן [תרנח-תשמג]: ונ”ל, שמקור הדברים הוא בבבלי תענית (דף ז ע”א): א”ל ר’ ירמיה לר’ זירא. ליתא מר ליתני. א”ל. חליש לבי ולא יכילנא. לימא מר מילתא

דאגדתא וכו’. ואפשר, שלפני

הרמב”ם היתה כאן הגירסא: מילתא

דבדיחותא וכו’ (שקיעין, ירושלים תרצט, ראש עמ’ 83).

גם היו מחברים שהראו על מאמרים

אחרים בתלמוד, ששמשו,

לדעתם, כמקור לרמב”ם

[2].

אמנם מצאנו בתלמוד ובמדרש כמה ענינים השיכים לבדיחותא בבית-המדרש:

א. אביי הוה יתיב קמיה דרבה. חזייה, דהוה קא בדח טובא, אמר: וגילו ברעדה כתיב! אמר ליה: אנא תפילין מנחנא. רבי ירמיה הוה יתיב קמיה דרבי זירא. חזייה דהוה קא בדח טובא. אמר ליה: בכל עצב יהיה מותר, כתיב! אמר ליה: אנא תפילין מנחנא (ברכות ל סע”ב)

[3].

ב. אמר רב יוסף: חלמא טבא – אפילו לדידי בדיחותיה מפכחא ליה (ברכות נה סע”א). פירש רש”י: אפילו לדידי. שאני מאור עינים.

ג. כי הא דרבה, מקמי דפתח להו לרבנן אמר מילתא דבדיחותא

. ובדחי רבנן. לסוף יתיב ב

אימתא ופתח

בשמעתא (שבת ל ע”ב; פסחים קיז ע”א)

[4].

ד. אמר ליה רבינא לרבא. היינו רגל היינו בהמה! אמר ליה. תנא אבות וקתני תולדות. אלא מעתה, סיפא דקתני השן מועדת, מאי אבות ומאי תולדות איכא? הוה קמהדר ליה בבדיחותא, ואמר ליה. אנא שנאי חדא ואת שני חדא (בבא קמא יז רע”ב). פירש רש”י: הוה קמהדר ליה. רבא לרבינא. בבדיחותא.

בשחוק. וא”ל אנא שנאי חדא,

רישא. ואת שני [חדא].

סיפא.

ה. … אהדר ליה בבדיחותא. חלש דעתיה דרב ששת. אישתיק רב אחדבוי בר אמי ואתיקר תלמודיה. אתיא אימיה וקא בכיא קמיה. צוחה צוחה ולא אשגח בה. אמרה ליה. חזי להני חדיי דמצית מינייהו! בעא רחמי עליה ואיתסי (בבא בתרא ט ע”ב). פירש רש”י: הוה קמהדר ליה. רב אחדבוי לרב ששת בבדיחותא. לפי שהיה רב ששת נכשל בתשובותיו. אשתתק רב אחדבוי. נעשה אלם. אתיא אימיה. דרב ששת. צווחה קמיה. שיתפלל עליו. להני חדיי. הדדים הללו. חדיי תרגום של חזה. דמצית מינייהו. שינקת מהן. [עי’ שם בתוספות, ד”ה אתיא, שהכונה לאמו של

רב אחדבוי, “והיא היתה מניקתו של רב ששת”. וכן פירש רבנו גרשום, שהכונה לאמו של רב אחדבוי, שהיתה מינקת של רב ששת.]

ו. רבי אבהו הוה רגיל דהוה קא דריש בשלשה מלכים. חלש. קביל עליה דלא דריש. כיון דאיתפח, הדר קא דריש. אמרי. לא קבילת עלך דלא דרשת בהו? אמר. אינהו מי הדרו בהו, דאנא אהדר בי … (סנהדרין קב סע”א). פירש רש”י: איהו מי הדרו בהו, מדרכם הרעה, דאנא אהדר (לי) [בי] מלדרוש …

ז. רבי היה יושב ודורש, ונתנמנם הצבור. בקש לעוררן. אמר. ילדה אשה אחת במצרים ששים רבוא בכרס אחת … זו

יוכבד, שילדה את

משה ששקול כנגד

ששים רבוא של ישראל … (שיר השירים רבה א טו ג).

וביומא ט סע”ב: וריש לקיש מי משתעי בהדי רבה בר בר חנה?! ומה רבי אלעזר, דמרא דארעא דישראל הוה, ולא הוה משתעי ריש לקיש בהדיה, דמאן דמשתעי ריש לקיש בהדיה בשוק יהבו ליה עיסקא בלא סהדי, בהדי רבה בר בר חנה משתעי?! ופרשו בתוספות ישנים: לא הוה מישתעי ריש לקיש בהדיה. כלומר, לא היה פותח לדבר עמו בשום מילתא דבדיחותא – – –

השוה גם: בראשית רבה, נח ג (מהדורת

תאודור-אלבק, עמ’ 621): ר’

עקיבה היה דורש, והציבור מתנמנם. ביקש לעוררן. אמר. מה ראת אסתר שתמלוך על קכז – – – . עי’ שם במנחת יהודה. וראה עוד ברכות כח ע”א (=ערובין כח רע”ב): רבי זירא כי הוה חליש מגירסיה, הוה אזיל ויתיב אפתחא דבי רבי נתן בר טובי

[5]. אמר: כי חלפי רבנן

[6], אז איקום מקמייהו ואקבל אגרא.

אך אין לראות בספורים אלו מקור המאמר כי הוו חלשי רבנן מגרסיהו, הוו אמרי מלתא דבדיחותא.

מאמרנו מצוי בספרי הראשונים ש

לאחר הרמב”ם, וכנראה,

ממנו לקחוהו.

כן כותב ר’

יעקב בר’ אבא מרי

אנטולי [סוף האלף החמישי]: … ההתמדה בדרישה ובעיון, מאין הפסק … היא רעה מאד. לפי שהשכל האנושי ישיגהו ליאות … עד שיבוא החכם לומר דברים

לא טובים. ולפי הענין הזה היה דרך

חכמי התלמוד לערב דברי

שמחה ושחוק בדבריהם. כמו שמצאנו להם: כי הוו חלשי רבנן מגירסא, הוו אמרי מלי דבדיחותא … (מלמד התלמידים [נכתב לאחר ד’תתקצ], בראשית, ליק תרכו, דף ב, ראש ע”ב).

וכן בדברי

ר’ לוי בן אברהם [המאה הראשונה לאלף זה]: ו

בדרש כִּוְּנוּ פעם לְהָשִׂישׂ וְחַזֵּק לב וְהַפְחִיד נמהרים (בתי הנפש והלחשים, מאמר א, בתוך: ידיעות המכון לחקר השירה העברית בירושלים, כרך חמישי, הוצאת שוקן, ברלין-ירושלים תרצט, עמ’ לז, חרוז רטז). ופירש המפרש: ובדרשות התלמוד יש קצת הגדות, לא היתה כונת אומרם כי אם להשׂישׂ ולשׂמח האנשים.

כמו שאמרו ז”ל. כי חלשי רבנן מגרסייהו, הוו אמרין מילי דבדיחותא.

וכן כותב בן-דורו, ר’

מנחם בר’ שלמה

המאירי [ה’ט-עה]: … לפעמים צריך שיכריח האדם עצמו, אף בחוץ מטבעו, לשנות בתכונת הדיבור, פעם …

דרך שמחה ולשון הבאי.

כאמרם ז”ל. כי חלשי רבנן מן גירסא, הוו אמרי מילי דבדיחותא (פרוש המאירי למשלי טו כג, פיורדא תרד, עמ’ 151).

ור’

הלל בר’ שמואל

מוירונה, אף הוא בן הדור, האריך בענין: דע, כי כל דברי רבותינו ז”ל נחלקים לששה חלקים. החלק … החמישי, הוא קיבוץ

דברי בדיחותא, כדי לשמח הלב ולהרחיבו, אחר שיגע החכם בעיון דק ובלמוד ההלכות החמורות והשִטוֹת העמוקות … אמנם החלק החמישי, שהוא כמו

דברי בדיחותא מקצתו. כמו: אתריגו לפחמי[ן], ארקיעו (זהבים וכו’) [לזהבין, ועשו לי שני מגידי בעלטה (ערובין נג ע”ב)]. וכמו פלוני ופלוני היה משתעי לשון חכמה. כמו: עלת נקבת (בברא יכעון) [בכדא ידאון] נשריא לקיניהון (צריך לראות זאת) (ועלו בגערה) ועלז בנערה אחרונית עירנית חננית

[7]. וכל דומה לזה.

ויש רבים ממנו בתלמוד – אל תחשוב שהוא

ענין בטל, אבל הוא

דבר מועיל, בעבור כי היתה כוונתם בזה לשמח הלב ולהרחיבו, כדי שלא ישתבש ולא יחלש שכלם מרוב היגיעה הגדולה שהיו יגעים בלימוד התורה ובהלכות החמורות, כדי להוציא המסקנא על אמיתתה. וכי (הא) [הוו] חליש[י] מגרסתם (הוו) [היו] משככים רתיחתם ומפיגים עצמם

במילי דבדיח[

ו]

תא, למען יתחדש כח שכלם (ויודכך) [ויזדכך] מוחם בשובם אל העסק. והיו צריכים לכך … ובעבור שלא היו רוצים להפסיק שמחתם בדברי בטלה, היו מדברים בלשון (תורה) [חידה] על צד טיול. וכל זה לשם שמים, להגדיל תורתם ולהאדירה … (תגמולי הנפש [השלימו בשנת ה’נא], חלק שני, ציון שני, ליק תרלד, דף כה-כו).

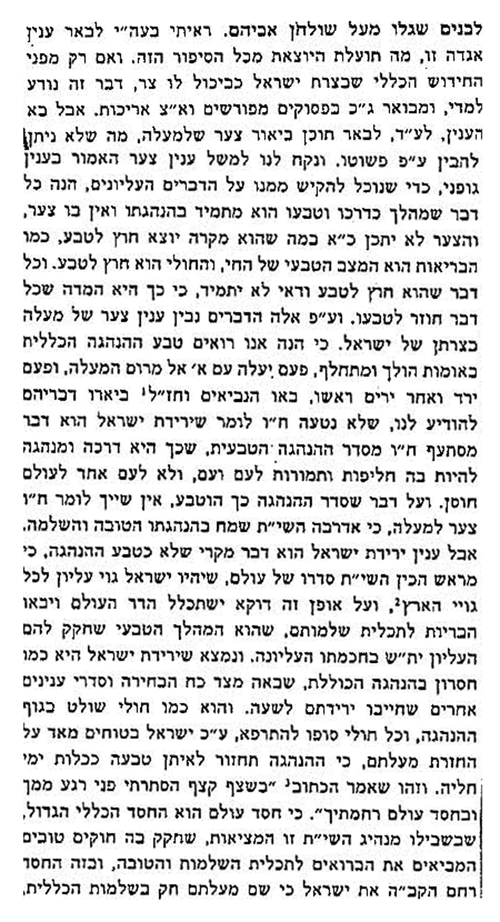

דברים דומים כותב ר’

שמואל צרצה, בהקדמת חבורו שכתב בשנת קכט: דע, כי

חכם אחד כתב, כי האגדות הנמצאות בתלמוד ובמדרשות יתחלקו למינים רבים. יש מהם שאמרום ז”ל, כאשר

אירע להם חולשה בהפלגת העיון, והכריחם הצורך

לשמח הנפש ולהקל מעליהם היגיעה והעצבון, היו מדברים בשעות כאלה

בדברי שמחה ובדיחותא. ולזה כונו

רז”ל באמרם: כי הוו חלשי רבנן מגרסייהו, הוו מתעסקי במילי דבדיחותא. וכאשר יעיין המשכיל בדברים הנאמרים בתלמוד בזה הדרך, יבין בעין שכלו, שאין הכונה בדברים ההם לשום ידיעה בעולם זולתי

הערת שמחה והטבת הנפש, להקל מעליהם יגיעת הלמוד וחזרת כחות הנפש לעניינם הראשון (ספר מכלל יופי, הקדמה. נדפס במאמרה של

גתית הולצמן, סיני, קט [חורף תשנב], עמ’ מ-מא).

גם כאשר בא ר’

יהודה מוסקאטו [רצה-שנ] לבאר

דעתו בסִבת האגדות, הוא מקדים להביא שתי דעות של

קודמיו: וכי תשאלך נפשך: מה זאת אשר חכמים הגידו דברי מוסר והשכל דרך משל וחידה? – – – הנה זאת תשובתה באלו ובכיוצא בהם, אחרי הקדימי, כי נאמרו בזה דברים שונים: מהם – דכד הוו חלשי מגירסייהו, הוו עסקו במילי דבדיחותא; ומהם – שהיה זה כדי לחדד שכלם. אמנם, אענה אף אני חלקי לאמר – – – (נפוצות יהודה, דרוש השלושה-עשר, ויניציאה שמט; במהדורת ארץ-ישראל וניו-יורק תשס, דף קכ ע”ב).

ובדור שלפני ר’

מנחם המאירי ור’

הלל מוירונה, כותב

רבנו יונה גירונדי [נפ’ ה’כד], הביא דבריו ר’

יוסף יעבץ בפירושו לאבות (ג יד): וכתב רבינו יונה ז”ל: הנה השי”ת נטע אזן באדם ויצר עין … יצר עינים, לראות ולהתעורר ולאחוז בחכמה ולהחזיק במלאכה, פן יאחזוהו ימי עוני; וכן העין, לעיין ולא לישן. הוא אומרו אל תאהב שנה פן תורש [משלי כ יג], וזה טעם שניהם, לסלק המונעים המטרידים אותו מעיונו בכל כחו, ולפי שאי-אפשר לעיין תמיד תחת היותנו בעלי חומר, כמו

שאמרו ז”ל: כי הוו חלשי רבנן מגירסייהו הוו עסקי במילי דבדיחותא. עכ”ל ר’

יוסף יעבץ. נראה, שכן היה לפניו בפירוש רבנו יונה למשלי. ולפנינו ליתא.

אנו מוצאים את המאמר גם בשלהי תקופת הראשונים. כן כותב ר’

שמעון בן צמח

דוראן [רשב”ץ; קכא-רד]: וכל מעשיך יהיו לשם שמים … וכשימצא גופו חלוש מהלימוד ויצטרך לטייל מעט בשווקים וברחובות, יכוין בזה כדי להרחיב לבו לשוב לתלמודו. ו

כמו שאמרו רז”ל. כי הוו רבנן חלישי מגרסייהו, הוו אמרי מילי דבדיחותא. וזהו ענין

האגדות הזרות הנמצאות בתלמוד (מגן אבות, פרק ב, משנה יב, ליפציג תרטו, דף לד ע”ב)

[8].

השוה גם דברי ר’

אברהם בן הרמב”ם [ד’תתקמו-תתקצח]: בחלק החמישי,

דרשות, דברו בהם

לשון הבאי ודמיון. החלק הזה בגמרא דפסחים [דף סב, סוף ע”ב]: אמר מר זוטרא. מאצל עד אצל הוה טעון ארבע מאות גמלי

[9] … והדרשה היא על שני פסוקים אלו. ועל שני הדרכים לא יסור דרש זה מהיותו

לשון הבאי, כי לא יתכן בעיני כל

בעל דעה, שיש דרש

על המקרא כולו משא ארבע מאות גמלי, וכל שכן

על שני פסוקים. הילכך אינו אלא

לשון הבאי.

וכבר ביאר זה זולתינו (ברכת אברהם, ליק כתר, עמ’ 6; ובמהדורת

ר”ר מרגליות, נספח לספרו של ר’

אברהם, מלחמות השם, ירושלים תשיג, עמ’ צב).

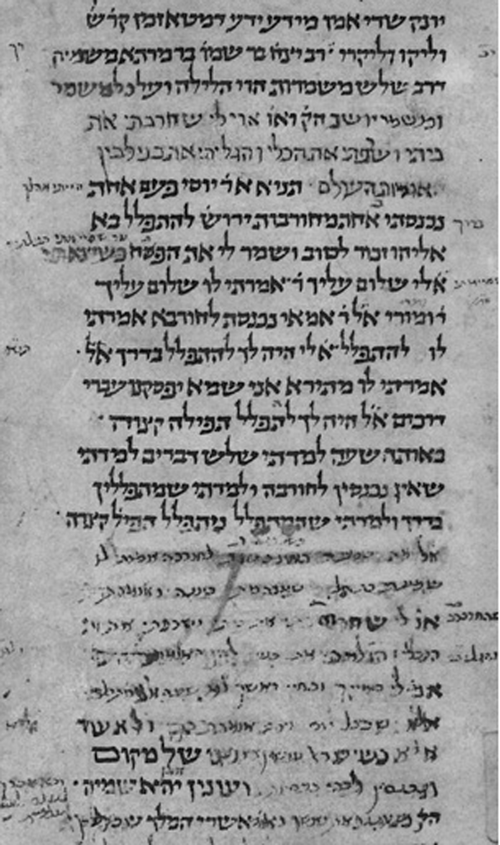

נוסח חדש לאגדה זו מצוי בפירוש,

המיוחס לרש”י, לדברי הימים א, סוף פרק ח: ועוד אמרו חכמים

בספר’ [בפסחים?]. ולאצל ששה בנים.

תליסר אלפי גמלי טעוני מדרשות!

את הגדרת ה’אגדות הזרות’ שבתלמוד הבבלי כמִלי דבדיחותא אנו מוצאים גם אצל ר’

ידעיה בדרשי הפניני [ל-ק]: ואמנם

ההגדות, וכל מה שבא מן הספורים הרבים בתלמוד ובמדרשות, ננהיגם על זה הדרך כלם. ונחלק אותם לפי זה לד חלקים – – – החלק השלישי. כל המאמרים המספרים בשום חדוש

יוצא מן המנהג, ועל הכלל בשנוי אי זה טבע, שלא ימשך לנו ממנו שום תועלת מבואר באמונה או שום חזוק. אלא שיזכירו על צד

הסִפוּר לבד,

לתועלת הרוחת התלמידים וצורך הכנסתם במלי דבדיחותא, להניח מכובד העיון ועמל הגרסא. וזה בספורי רבה בר בר חנא [בבא בתרא עג ע”ב – עד ע”א], וזולתם מהדומים להם רבים (“כתב ההתנצלות, אשר שלח החכם

אנבוניט אברם [=ידעיה בר אברהם בדרשי] ל

רשב”א“, בתוך: שו”ת הרשב”א, ח”א, סימן תיח, ירושלים תשנז, דף רכא סע”א – רכב רע”א).

ממנו לקח ר’

יצחק אברבנאל, אלא שהוא מחלק את האגדות ל

ששה מינים. וזה לשונו: המין החמישי, מה שנזכר על צד הסיפור ממין

הנמנעות, מבלי שימשך לנו ממנו שום תועלת מבואר באמונה, אלא שנזכר על צד

הסיפור בלבד

לתועלת הרווחת התלמידים, והצורך להכניסם במילי דבדיחותא, להניח להם מכובד העיון ועמל הגירסא, כסיפורי רבה בר בר חנא והדומה לו (ישועות משיחו, החלק השני, הקדמה, קניגסברג תרכא, דף יז ע”א).

וכתב ר’

אברהם אבן-עזרא [ד’תתמט/תתנ-תתקכז] בהקדמת פרוש התורה: מפרשי התורה הולכים על

חמשה דרכים – – – הדרך הרביעית, קרובה אל הנקודה / ורדפו אחריה אגודה. זאת דרך החכמים / בארצות יונים ואדומים / שלא יביטו אל משקל מאזנים / רק יסמכו על דרך דרש, כלקח טוב ואור עינים – – – גם יש דרש

להרויח נפש חלושה בהלכה קשה – – –

[10].

וכן הוא כותב בהקדמת פרושו לאיכה: אנשי אמת יבינו מדרשי קדמונינו הצדיקים / שהם נוסדים על קשט וביציקת מדע יצוקים / וכל דבריהם כזהב וככסף שבעתים מזוקקים. / אכן,

מדרשיה – אל דרכים רבים נחלקים: / מהם חידות וסודות ומשלים גבוהים עד שחקים / ומהם

להרויח לבות נלאות בפרקים עמוקים / ומהם לאמן נכשלים ולמלאת הריקים – – –

[11].

והשוה דברי

הרשב”א: תחילה אעירך על ענין ההגדות שבאו בתלמוד ובמדרשים. דע, כי באו מהם בלשון עמוק, לסיבות רבות – – – ועוד יש להם סיבה אחרת, גילו אותה הם ז”ל בקצת המדרשים, והוא, כי לעתים היו החכמים דורשים ברבים ומאריכים בדברי תועלת, והיו העם ישנים, וכדי

לעוררם היו אומרים להם

דברים זרים, לבהלם ושיתעוררו משנתם – – – (חידושי הרשב”א, לרבינו

שלמה ב”ר אברהם

אדרת; פירושי ההגדות. יוצא לאור על פי כתבי יד … הערות ובאורים, מאת

אריה ליב …

פלדמן, ירושלים תשנא, עמ’ נח-נט).

והובאו הדברים,

בשמו, על ידי ר’

מאיר אלדבי, בספרו שבילי אמונה, הנתיב השמיני, ורשה תרמז, דף 166 רע”א.

גם מצאנו לרבותינו האחרונים שהביאו את המאמר הזה.

כן כותב הגאון

יעב”ץ [תנח-תקלו]: … כי הנפש תלאה ותעכור המחשבה, בהתמדת עיון הדברים הכעורים, כמו שילאה הגוף בעשותו המלאכות הכבדות, עד שינוח וינפש, ואז ישוב למזגו השוה. כן צריכה הנפש גם כן להתעסק במנוחת החושים בעיון, לפתוחים ולענינים הנאים, עד שיסור ממנה הלאות,

כמ”ש כי הוו חלשי רבנן מגרסייהו, הוו אמרי מילתא דבדיחותא (מגדל עוז, בית מדות, נוה חכם, חלון ב, סימן א, ורשה תרמז, דף 70, עמוד א).

והרי זה לשון

הרמב”ם, בשמונה פרקים, שהבאנו בראש המאמר [שבתי וראיתי בפתיחה לחלון א: …

נעתיק כאן משמנה הפרקים הידועים להר”מ ז”ל, שהקדים למס’ אבות,

פרקים שנים … עכ”ל. למעשה העתיק מן הפרק

הרביעי רק את

חציו הראשון. ואולם את הפרק

החמישי, העתיק

כולו.]

אף כי לא שמענו עד עתה על מי ש

נהג בפועל כהמלצת מאמרנו, היו גם כאלה. אחד מהם הוא ר’

אברהם טריוויש, שבספרו, שהדפיס בשנת שיב, לאחר שהאריך במִלי דבדיחותא, שאין לסמוך להלכה על דעת הנשים, הוא כותב: – – – ויושבת תחת הלחי וקורה, בשבת, ומוציאה הרעלות והפארים / והצעד”ות והקשורים / ואומרת שם שיר השירים / ושם משׂחקת באגוז”ים עם נערים / ולא מחינן בידייהו, כמצות דברי סופרים / כי אפילו נמחה בידה, עשרים נשיאים וממשפחת רמים וגבורים / ועמנו מאתים חכמים מלכי רבנן ושרים / – כלנו לפניהן כעזים מאתים ותישים עשרים. וכד הוו חלשי רבנן מגירסייהו, הוו אמרי מילי דבדיחותא / ובתר הכי הדרי לשמעתא (ברכת אברהם, חלק ראשון, סימן נח, ויניציאה שיב, דף כג ע”א).

כאן הוא מוסיף: ובתר הכי הדרי לשמעתא. תוספת זו אינה במקורות קדומים והיא שלו. משום ש

קטע את פלפולו

ההלכתי במִלי דבדיחותא, הוא מודיע שהוא חוזר ל

שמעתא.

וכן הוא נהג גם להלן. שם הוא מודיע במפורש את סִבת התעסקותו במִלי דבדיחותא. וזה לשונו: והנני אומר. דכד הוו חלשי רבנן מגירסייהו, הוו אמרי מילי דבדיחותא / ובתר הכי הדרי לשמעתייהו.

אנן נמי נעביד הכי, דידענא, דמאן דיליף בסיפרא הדין, לימא עילואי: כמה ארכן הוא זה. ומשום הכי כתבית בכמה דוכתי – בפרט בשלשה חלקים ראשונים וגם באי זה מקומות מועטין בזה החלק הרביעי, גם בשאר חלקים דלקמן – מילי דבדיחותא, דלשמוחי לרבנן הוא דבעינא / והכא נמי לא שנא. כי בזה

אמשוך לב הקוראים בדברי אריכותי / לו חכמו ישכילו זאת יבינו לאחריתי – – – (חלק רביעי, סימן קפח, דף קעא ע”א).

גם ר’

אפרים אליקים גצל מלזק [תקמ-תריד], נהג כך. וזה לשונו:

עתה באתי להוציא מלבן של שלשת הרבנים הללו

[12], שלא יהיו להוטין עוד אחר כח המדמה שלהם – ובכבודן של רבנן דחלשי מגירסייהו, אסיים הגמטריאות במילתא דבדיחותא, ואכחד שלשת הרואים במחזות שוא ומדוחים אלו, בחזקת יד גימטריא אחת.

להתוודע ולהגלות! דאינהו לא חזו באספקלריא המאירה של הקלירי, אך מזלייהו חזי באספקלריא שאינה מאירה, בבואה דבבואה מדמות של עצמם. רצוני לומר, שהחרוז אנסיכה מלכי / לפניו בהתהלכי / אומצו בהמליכי, שעולה, לדעתם, כמספר אני אלעזר בירבי יעקב קיליר, 1164, עולה

ממש:

אני שלמה יהודה ליב הכהן רפאפורט, 1164;

אני ליפמאן דאקטיר צונץ מברלין, 1164;

הקטן משה הלוי לאנדא מדפיס מפראג, 1164 – – –

ומי זה חסר-טעם, שישתגע לומר, שפיוט אנסיכה חיברו אחד משלשת הרבנים האלו, בעבור שעולה החרוז כחתימתם – – – עכ”ל

רא”א מלזק (ראביה, אופן תקצג, דף יט ע”ג, סעיף ז).

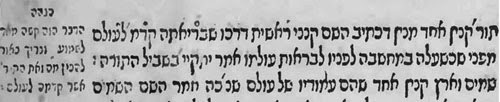

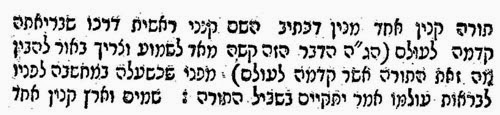

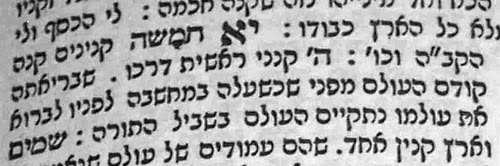

[1] בהגהה שנדפסה בשולי גליון שמונה פרקים הנדפס בתלמוד בבלי, נאמר:

לפי שעה לא ידעתי מקומו. ובשבת ל ע”ב איתא, דרבא מקמי דפתח להו לרבנן, אמר מילתא דבדיחותא וכו’. וכן כותב

יעקב ריפמן: לא אדע מקום המאמר הזה. ובשבת ל ע”ב כתוב בדרך אחרת. יעויין שם (עיונים במשנת הראב”ע, בעריכת

נפתלי בן-מנחם, ירושלים תשכב, עמ’ 29).

[2] כמו ר’

יודא ליב אינדעך, לאחר שמביא לשון

רמב”ם, הוא מעיר: לשון זה

לא מצינו בגמרא, אבל כונת הרמב”ם על שני מאמרי חז”ל, מברכות כח ע”א, ועירובין כח ע”ב: ר’ זירא כי הוי חליש מגירסיה וכו’. עי”ש. דמזה ראיה, דהנפש צריכה גם כן מנוחה מעבודתה, כמו הגוף. ומרבה דהכא [=שבת ל ע”ב], שמותר להתעסק במנוחת החושים בענינים נאים, כמו מילתא דבדיחותא וכדומה, עד שיסור מנפשו הליאות ותשוב למזגה (זהרי הש”ס, ח”א, לשבת ל ע”ב, לונדון תשלד, דף 88 רע”ב). ודבריו דחוקים, שכן בברכות וערובין, אמנם נזכר חליש מגירסיה, אך אין שם זכר לבדיחותא!

[3] ראה גם בהמשך (ל סע”ב – לא רע”א): מר בריה דרבינא עבד הלולא לבריה. חזנהו לרבנן דהוו קבדחי טובא. אייתי כסא דמוקרא, בת ארבע מאה זוזי, ותבר קמייהו, ו

אעציבו. רב אשי עבד הלולא לבריה. חזנהו לרבנן דהוו קא בדחי טובא. אייתי כסא דזוגיתא חיורתא ותבר קמייהו, ו

אעציבו.

[4] בספר הזוהר (תזריע, מז ע”ב), נזכר מאמר דומה: דאמר רבי שמעון לרבי אבא: תא חזי, רזא דמִלה, לא נהיר חכמתא דלעילא ולא אתנהיר אלא בגין

שטותא דאתער מאתר אחרא, ואלמלא האי נהירו ורבו סגיא ויתיר לא הוה, ולא אתחזיא תועלתא דחכמתא – – – וכך לתתא, אלמלא לא הוה שטותא שכיח בעלמא, לא הוי חכמתא שכיח בעלמא. והיינו ד

רב המנונא סבא, כד הוה ילפין מניה חברייא רזי דחכמתא, הוה מסדר קמייהו פרקא דמלי ד

שטותא. בגין דייתי תועלתא לחכמתא בגיניה. הדא הוא דכתיב: יקר מחכמה מכבוד סכלות מעט [קהלת י א], משום דהיא תקונא דחכמתא ויקרא דחכמתא – – –

ור’ חיים הכהן מארם צובה מביא את הזוהר בתוספת באור: כדאיתא בזוהר, כי הא דרב המנונא סבא ע”ה, דהוה אמר פרקא דשטותא ובדחי חברייא,

ואחר כך פותח בתורה (מקור חיים, ח”ג, הלכות פסח, סימן תמד, ס”ק ג, פיעטרקוב תרלח, דף מא ע”ד).

[5] בערובין: ויתיב אפיתחא דרב יהודה בר אמי.

[6] בערובין: כי נפקי ועיילי רבנן.

[7] ערובין, שם: אמהתא דבי רבי, כי הות משתעיא

בלשון חכמה, אמרה הכי. עלת נקפת בכד; ידאון נשריא לקיניהון … רבי אלעאי … עלץ בנערה אהרונית אחרונית עירנית.

[8] דברי

רשב”ץ הובאו במדרש שמואל, לַמִּשְׁנָה,

במקוצר ובשנויי לשון. המחבר, ר’

שמואל די-אוזידה, מתנצל על כך וכותב: והואלתי לכתוב ולהאריך

רוב דבריו של רשב”ץ ז”ל, ואף אם

הוא האריך יותר ויותר, לפי שזה הוא עיקר גדול בהנהגת האדם ובכל פרטיו.

מאידך, הוסיף המעתיק,

בתוך דברי רשב”ץ,

שני חדושים משל עצמו, הבנוים על

יסוד דברי רשב”ץ. הוא מודיע על כך בציון ‘ונ”ל הכותב’ (בראש החדוש הראשון) ובציון ‘ואני הכותב נ”ל’ (בראש החדוש השני). ונצטט את חדושו השני, הקשור יותר לעניננו: ו

אני הכותב נראה לי, שזה שאמר דוד המלך ע”ה: ואתהלכה ברחבה. כלומר, לטייל ברחבה, לפי שפקודיך דרשתי, וחליש דעתאי מן הגרסא, ולזה אני הולך לטייל. ולזה לא אמר ואהלך ברחבה, אלא ואתהלכה, מן ההתפעל, שהוא מורה על הטיול. וכמו ש

ארז”ל כי הוו רבנן חלשי מגרסייהו אמרי מילי דבדיחותא. וזהו ענין

ההגדות הנמצאות בגמרא – – –

[9] לפנינו: בין אצל לאצל טעינו ד מאה גמלי דדרשא. פירש רש”י: מאצל לאצל.

שני מקראות הן, ופרשה גדולה ביניהן. ולאצל ששה בנים [ד”ה א ח לח], וקא חשיב ואזיל הבנים. וסיפא דפרשתא אלה בני אצל (ט מד).

אמנם בספר הערוך, ערך אצל: בגמ’ … בין אצל לאצל טעון ארבע מאה גמלי דרשא. פי’.

פסוק בדברי הימים [א ח לח] הוא, ותחלתו אצל וסופו אצל. ואף על פי

שקרובין זה לזה, הוי טעון ת גמלי דרשא.

וראה גם ספר מעריך, לר’

מנחם די לונזנו: ו

אני אומר. לא כי! אלא ב פסוקים דומים הם. אחד בסוף סימן ח, ואחד בסוף סימן ט. ובין זה לזה מה פסוקים, כמנין אדם. עכ”ל

רמד”ל. ותמיהני,

שהרי זה פירוש רש”י בפסחים!

[10] הביא דבריו ר’

יוסף יעבץ, בפֵרושו לאבות ג יד. עי”ש. וראה:

יעקב ריפמן, עיונים במשנת הראב”ע, בעריכת

נפתלי בן-מנחם, ירושלים תשכב, עמ’ 29-28.

[11] וראה:

יעקב ריפמן, שם, עמ’ 48.

[12] שלמה יהודה הכהן רפופורט (שי”ר),

ליפמן צונץ ו

משה הלוי לנדא, שעל סמך

גימטריא יחסו את הפיוט אנסיכה מלכי לר’

אלעזר הקלירי.