Censorship in the Sefer Chofetz Chaim?

(Another chapter of R. Shmuel Ashkenazi's Latest Work)

In the past I received requests for more information about R. Ashkenazi. What follows is a small biography (along with an appeal for help) on him written recently.

מוקירי תורה וחכמיה, נדיבים שבעם! דומה שאין איש אשר לא הגיעו שִׁמְעוֹ של האיש הנכבד, הנאמן בכל בית הספרים היהודי, ר' שמואל אשכנזי שליט"א. ספרו "אלפא ביתא קדמייתא דשמואל זעירא" שיצא לאור בירושלים, בשנת ה'תש"ס, פתח בפני כלל חכמי ישראל וחובבי תורה את שערי אוצרותיו, חשף בפניהם מעט מבקיאותו המפליאה והטעימם מרעיונותיו והגיגיו הנעימים אלא, שהעומדים משתאים מול היקף המידע והידע הנגלה מבין דפי "אלפא ביתא קדמייתא'', ודאי יופתעו כפליים בשמעם שאין זה אלא מעט שבמעט מאוצרותיו של ר' שמואל שעודם בכתובים, מצפים לאנשי רוח ומביני דבר שירתמו לסייע בהוצאתם לאור עולם והפצתם להגדיל תורה ולהאדירה.ר' שמואל – המקפיד בתוקף שלא להוסיף על שמו כל תואר נוסף פרט לר' – נולד ביום יא בטבת תרפ"ב. בשנות העשרים המוקדמות לחייו כתב עשרות ערכים ב"אנציקלופדיה לתולדות גדולי ישראל" (בעריכת ד"ר מרדכי מרגליות, ירושלים תשו-תשי), בכרכים הראשונים של ה"אנציקלופדיה העברית" ובשתי אנציקלופדיות אחרות של הוצאת 'מסדה'. בהמשך עסק בעריכת ספרים ב"מוסד הרב קוק", ב"מכון תורה שלמה" ובאופן עצמאי. בראשית שנת תשכ"ז ועד פרישתו לגמלאות עבד ב"מפעל הביבליוגרפיה העברית" שבבית הספרים הלאומי בירושלים, ומבחינה מסוימת הוא היה מתווה דרכה ביחד עם הביבליוגרף הבלתי נשכח מר נפתלי בן-מנחם ז"ל. אף לאחר שפרש לגמלאות הגיע למקום בכל יום שלישי וקיבל בסבר פנים יפות את כל המתייעצים עמו, בהם בכירים באקדמיה שעמדו לפתחו ושאלו לעצתו. בשנת תשס"א נתמנה כחבר כבוד בהוצאת הספרים המיתולוגית "מקיצי נרדמים", לאור בקשתם המפורשת של מזכירה וחבריה.החל משנת תש"ד (בהיותו בן-שמונה עשרה) החלו להתפרסם מאמריו הרבים בבמות מכובדות ומפורסמות, ולעיתים עוררו תגובות חריגות (כמו מאמריו "טעויות סופרים" ו"מילונות עברית כיצד?"). בין לבין נענה לשאלות שבכתב שהופנו אליו מכל קצווי הארץ ומחוצה לה, ושיגר במשך השנים כאלפיים מכתבי תשובה. בין ספריו המופתיים ניתן למנות את: "הגדה שלמה", ירושלים תשט"ו; "אוצר ראשי תבות", ירושלים תשכ"ה; "הרי"ף ומשנתו", ירושלים תשכ"ז. ואת עריכתו המופתית ניתן לראות בספר "משלי ישראל ואומות העולם", ירושלים תשכ"ד. טביעת אצבעותיו המיוחדת ניכרת בספרים רבים אחרים, כמו: "בן המלך והנזיר", תל-אביב תשי"א; "אוצר המשלים והחידות", ירושלים תשי"ז; "מחברות עמנואל הרומי", ירושלים תשי"ז; "אוצר פתגמים וניבים לטיניים", תל-אביב תשי"ט (מהדורה שניה: ירושלים תשמ"ב); "צרור המור", בני-ברק תש"נ; "אוצר הספר העברי", ירושלים תשנ"ה; "אוצר תפילות ישראל", א-ב, ירושלים תשנ"ז.כתיבתו של ר' שמואל יחודית ומאופיינת: קצרה, ענינית ומקיפה, ובעיקר – מדויקת. רגיל היה, אף לאחר הגיעו לגבורות, לכתת רגליו רק כדי לראות את הדברים בדפוס הראשון או לבדוק אם אכן הפנייה כלשהי מדויקת וכדומה.בימים אלה הולכים ומותקנים לדפוס שני ספרים נוספים ממעיינותיו של רבי שמואל, הלא הם "אלפא ביתא תנייתא" המהווה המשך ישיר לספר הראשון וכולל בתוכו בירורים מקיפים למקורם של ביטויים, פתגמים ואמרות עממיות, ו"אלפא ביתא תליתאי" הכולל בירורים בנושאים כלליים. שניהם בדרכו הייחודית של ר' שמואל, האוצר בזכרונו וברשימותיו רבבות מקורות עלומים וגנוזים ומעבדם בתבונתו וחוש ביקורתו הנודע.כל אחד מן הספרים מתפרס על פני שלושה כרכים, ויחדיו כוללים הם למעלה מ-2500 עמודים מלאים וגדושים בדברי תורה וחכמה ופנינים נפלאות מעולם הספר היהודי על כל גווניו ואפיקיו.את מלאכת עריכת הספרים לקח על עצמו ידידנו ר' יעקב ישראל סטל הי"ו, אשר ביד אמן, במתינות ובתבונה הופך את פיסות הנייר, פנקסיו ופתקאותיו של רבי שמואל לכדי יצירה מפוארת כיאה לכבוד יוצרה ותורתו.אולם, ידידינו הנעלים, הוצאות ההדפסה כבדו מנשוא! איש פרטי וצנוע הוא ר' שמואל, לא מכוני מחקר ולא קרנות לו לאיש, לא בית הוצאה לאור ולא בית מסחר ספרים. מעודו, נחבא ר' שמואל אל הכלים ואינו מבקש את פרסומו הראוי לו. לולי תושייתם של אוהבי תורה ודעת שנגה עליהם מעט מאורו של רבי שמואל, כי אז היה נותר אלמוני, הוא ואוצרותיו העצומים.ועתה, עם סיום מלאכת עריכת שני הספרים שלפנינו, הרי הם יושבים ומצפים לגואל, איש אשר רוח בו ולב מרגיש לו להבין את יקרתם של דברי תורה אלו, וישאוהו רעיוניו להטות שכמו לעזרת ר' שמואל ולשקוד על תקנת חכמי ישראל, במתת יד נכבדה כשיעור הנצרך להדפסת הספרים היקרים. עורכי הספר אינם מבקשים דבר על המלאכה הכבירה והזמן היקר והרב שהושקעו בהתקנת הספרים לדפוס. זאת עשו בלב רחב ובנפש חפצה, מאשר יקרו בעיניהם נכבדו פניניו של ר' שמואל. אולם עלות ההדפסה כבדה עליהם ואין לאל ידם להשלים את המשימה ללא עזרת ה' בגיבורים.חושו, ידידינו, חושו לעמוד לימין ר' שמואל ולעזרת כל אוהבי תורה, והרימו תרומתכם להדפסת הספרים הנכבדים הללו! שוו בנפשכם מה רבה התועלת העולה ממאמריו ומחקריו הנעימים של ר' שמואל להרמת קרן התורה וכבודה; הוכיחו קבל עם ועדה כי כבוד התורה יקר בעיני הוגיה וכי אין מניחים הם לדברי תורה להיות מונחים בקרן זווית, גנוזים וכמוסים באין דורש!!

And now for the main article:

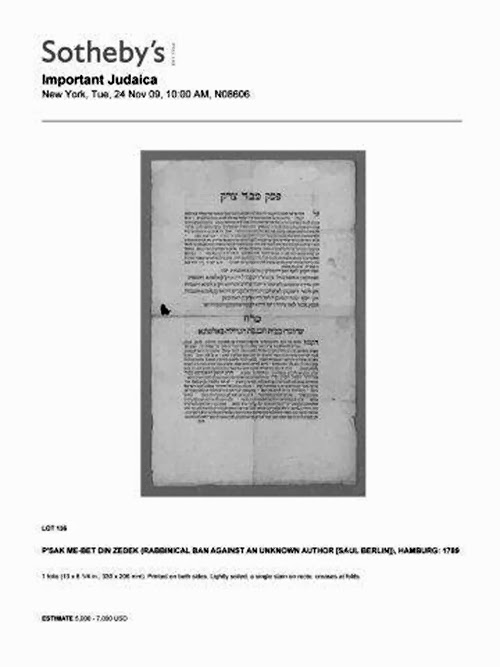

לכבוד מערכת בית יעקב ב"ה. ה במנחם-אב תשלאמ"נ,מזמן לזמן מזדמנים לפני גליונות של ירחונכם הנכבד, שאני מוצא בהם ענין ומתענג על קריאתם. לא כן קרני הפעם הזאת. הגיע לידי גליון 137 (תאריך הופעתו [סיון תשלא?] לא צוין!), ומיד עם פתיחתו נתקלתי במאמר גדול, מאת יצחק מ. שמואלי, המשתרע לארכם ולרחבם של שני עמודים שלמים (5-4), ומעליו שלוש כותרות מרעישות: 1) על משמר קדשי האומה. 2) מיהו "צנזור" במהדורות חדשות של ספרי-קודש? 3) תגלית מדהימה על מעשה-זיוף מגמתי בכתביו של בעל "חפץ חיים" זצ"ל.וזה "מעשה הזיוף": בקונטרס שפת תמים, לבעל חפץ חיים, פרק ד, נאמר: וראיתי בספרים מעשה נפלא שהיה בימי הריב"ש, שבא אחד בגלגול סוס והיה עובד בכל כחו כדי לשלם את חובו. ואילו "במהדורות החדשות… שהופיעו לאחר השואה (ונדפסו מתחילה באמריקה, על-ידי יורשיו של בעל המחבר) נחלף הנוסח המקורי לפי כתב-ידו של החפץ חיים הקדוש בנוסח 'מתוקן' כזה: 'וראיתי מעשה נפלא, שהיה בימים הראשונים'".כותב המאמר שואל: "מה היתה מטרתו ותכליתו של 'שינוי' זה?" והוא משיב: "אין מפלט, כמובן, מאותה מסקנה הכרחית, שלא היה, כנראה, לרוחם ולטעמם של בעלי הזכויות של המהדורה החדשה, שבעל החפץ חיים מזכיר ומסתמך בספרו על מעשה נפלא שמתייחס אל מייסד החסידות רבי ישראל בעל-שם-טוב… הם התביישו בכך, הם לא יכלו לבלוע זאת, הם נרתעים ממש בפני ההשפעה העלולה להתקבל מהתייחסותו של החפץ-חיים אל הבעש"ט" ולכן זייפו וסילפו את דברי המחבר "כדי לחבל ברגשי-האחווה שנתרקמו אצל… חסידים ומתנגדים".אין הכותב נוקב בשמם המפורש של "בעלי הזכויות". אך הכל יודעים, שהכוונה לחתן המחבר "הרב פנחס מענדיל יוסף זאקס, ר"מ דישיבת חפץ חיים בראדין" אשר הוציא מחדש את ספרי חותנו, בניו-יורק, בשנת תשיב ובשנת תשך. ואותו מאשים הכותב ב"מעשה מביש כזה" אשר "בדין הוא ש… יזעזע את דעת-הציבור שלנו"."וכדי שלא לפרסם אשמה מזעזעת כזו… בלי ביסוס עובדתי מלא" טרח הכותב וצירף למאמרו שלושה פקסימילים המוכיחים באופן "מדעי" מוחלט את "הסילוף הגס והמביש… שנעשה בחיבורו של החפץ חיים"."והיות שהמדובר… בסילוף מכוון שיש בו מגמה שקופה בהחלט… מן הדין להרים קול זעקה ומחאה, להוקיע קבל עם ועדה את הסילוף הנורא והמחריד ולתבוע במפגיע תיקון הדבר מידי אלה הנושאים באחריות לכך!"אם באמת ובתמים נתכוון הכותב לזעזע את דעת הקוראים ולהזעיקם למחאה, הרי עלה הדבר בידו… שכן אני נזדעזעתי למקרא דברי ההשמצה והטחת ההאשמות כלפי חתן המחבר, אשר ריבה פעלים לתורה ויראה בהפיצו ספרי ההלכה והמוסר של חותנו בעל חפץ חיים. ואומר אל לבי: מצוה להציל עשוק מיד עושקו ולהגן על כבודו של ת"ח מפני המתנפלים עליו בשצף קצף על לא חמס בכפו ולא עולתה בו.ואם עדיין הייתי מהסס בדבר וחושש, שלא להרבות בחלול כבוד התורה על ידי הבעת מחאתי ברבים, בא המאורע דלהלן וחיזק את החלטתי לפרסם ברבים את בטולו של המאמר הנז'.וזה אשר קרני [אין מקרה בעולם, אלא כי הקרה ה' לפני את הדבר הזה!]. ביום המחרת (לאחר קבלת הגליון הנז') נכנסתי לבית המדרש להתפלל שחרית. והנה על השולחן לפני מונח ספר חפץ חיים, הוצאת ועד שמירת הלשון, ירושלים תשכז, ונספח אליו קונטרס שפת תמים. פתחתיו בעמ' טו ואראה בגליון (ליד המלים "מעשה נפלא שהיה בימים הראשונים") הערה כתובה בדיו אדומה על ידי חסיד-שוטה: המילה ראשונים היא זיוף מוחלט ושפל בדברי רבנו וצ"ל בימי הריב"ש (ר' ישראל בעש"ט) כהוצאה הראשונה.ויהי כראותי עד היכן הדברים מגיעים, נזדרזתי לקרבה אל המלאכה: לבדוק את הנוסח הנדפס בהוצאות השונות של קונטרס שפת תמים. לאחר יגיעה מרובה נתברר לי, שקונטרס זה נדפס על ידי מחברו, כנספח לחלק א של "ספר שמירת הלשון… והוא השלמת הספר חפץ חיים", בשנת תרלו, וחזר ונדפס לא פחות מעשרים ושלוש פעמים*. והרי רשימת ההוצאות השונות (אלה שלא ראיתי מסומנות בכוכב):1* ווילנא, דפוס ר' יהודה ליב מ"ץ, שנת שמר פיו [תרלו], 1876.2 הוצאה שניה, ווילנא, דפוס הנ"ל, תרלט, 1879. סודרה ונדפסה דף על דף על פי 1.3* הוצאה שלישית. נדפסה בין תרם לתרמג. והיא ששימשה אבטיפוס להוצאות הבאות, שאינן אלא דפוסים-סטראוטיפיים או דפוסי-צלום של 3.4 "הוצאה שלישית", ווארשא, דפוס ר' יוסף אונטערהענדלער, תרמד, 1884. ד"ס של 3.5* "הוצאה שלישית", ווארשא, דפוס הנ"ל [תרמח?]. בשער: תרמד, 1884. ד"ס של 4.6 "הוצאה שלישית", ווארשא, דפוס בוימריטטער וחתנו גאנשאר, תרן, 1890. ד"ס של 5.7 "הוצאה רביעית", ווארשא (דפוס ב' טורש, צנז' 1892 [תרנב]). ד"ס של 6.8 "הוצאה חמישית", ווארשא (דפוס בוימריטטער), תרנה, 1895. ד"ס של 3?9 "הוצאה חמישית", ווארשא (דפוס אונטערהענדלער, צנז' 1902 [תרסב]). בשער: תרנה, 1895. ד"ס של 8.10 "הוצאה חמישית", ווארשא (דפוס לעווין-עפשטיין, 1910 [תרע]). ד"ס של 7.11 "הוצאה חמישית", ווארשא (דפוס הנ"ל, 1914 [תרעד]). ד"ס של 10.12* "הוצאה שלישית" (הוצאת הרב הילל גינסבורג, ראדין), ווארשא (דפוס פומפיך), [תרף?]. ד"ס של 4?13 "הוצאה שלישית", ווארשא (דפוס פימענט), [תרפ-]. בשער: דפוס יוסף אונטערהענדלער, תרמד. ד"ס של 12.14 "הוצאה שלישית", ווארשא (דפוס לעווין-עפשטיין), [תרפח]. ד"ס של 13.15 "הוצאה שלישית", שנגהי [תשד?]. ד"צ של 12.16 הוצאה רביעית", [גרמניה תשז?]. בשער: ווארשא. ד"צ של 7.17 "הוצא ע"י חתנו הרב מנחם מענדיל יוסף זאקס", ניו יורק תשיב. ד"צ של 8.18 "הוצאת הרב הרשקוביץ", (ירושלם תשטז). סודרה ונדפסה על פי 8.19 "הוצאת אגודת חכמי סלאוויטא, בני ברק", ירושלים (תשך). ד"ס של 18.20 "הוצא ע"י חתנו הרב מנחם מענדיל יוסף זאקס", ניו יורק תשך. ד"צ של 17.21* "הוצאת ועד שמירת הלשון", ירושלים תשכה. סודרה ונדפסה על פי 8.22 "הוצאת הרב הרשקוביץ", ירושלים [תשכז]. ד"ס של 18.23 "הוצאת ועד שמירת הלשון", ירושלים תשכז. ד"ס של 21.24 כנ"ל, ירושלים [תשל]. בשער: תשכז. ד"ס של 23, אלא שבמהדורה זו נספח קונטרס שפת תמים לספר שמירת הלשון ולא לספר חפץ חיים.לא עלה בידי למצוא טופס שלם** מן ההוצאה הראשונה, אך היו למראה עיני תשע עשרה מן ההוצאות הבאות.והנה בעשר מהן נדפס: בימי הריב"ש (2 4 6 7 10 11 16-13), ובתשע: בימים הראשונים (8 9 20-17 24-22).מתשע מהדורות אלו נדפסו שבע לאחר השואה, ואילו שתים מהן נדפסו כבר בימי המחבר ובהסכמתו: הראשונה (מס' 8) בשנת תרנה [כיובל שנים לפני השואה] והשניה (מס' 9) בשנת תרסב. בהוצאת תרנה נדפס: "שהיה בימים הראשונים" ושתי האותיות האחרונות (ים) יוצאות מחוץ לשורה, אך בהוצאת תרסב סודרה השורה מחדש, כדי ליישרה עם חברותיה, ונדפס: שהי' בימים הראשוני'.כל המשוה את שתי ההוצאות של הרב זאקס (ניו יורק תשיב ותשך) להוצאת ווארשא תרנה, יתברר לו למעלה מכל ספק שהראשונות אינן אלא דפוסי-צלום של האחרונה! וחתן המחבר לא תיקן, לא סילף ולא זייף את הנוסח המקורי. ואף ההוצאות האחרונות, שסודרו מחדש, נדפסו על פי ווארשא תרנה. ואין לתלות בוקי סריקי במוציאיהן. נמצינו למדים, שאך לשוא שקד הכותב (המסתתר בכנוי "יצחק מ. שמואלי") למלא שש עמודות (450 שורות!) בדברי הבל וריק ובהטחת האשמות שוא ללא כל יסוד.ואם ישאל שואל: מה טעם תוקן הנוסח בהוצאת תרנה? אין בפי תשובה ודאית. אך ניתן לשער, כי המחבר "נכשל" בפענוח הריב"ש וסבור היה שהוא בעל שו"ת הריב"ש, היינו ר' יצחק בר ששת, מחכמי הראשונים (ה'פו-קסח), וכאשר נודע לו מקור הסיפור (שבחי הבעש"ט!) ונתבררה לו זהותו של הריב"ש שהוא ר' ישראל בעל שם, רבן של חסידים, הלך והחליף את המלים "בימי הריב"ש" במלים אחרות (בימים הראשונים). ואך צחוק עשה לנו הכותב בקביעתו המגוחכת כי "לפני קרוב למאה שנים, עת המתיחות בין המתנגדים ולבין החסידים… בא בעל ה'חפץ חיים' לעשת צעד פייסני כזה, להזכיר את הריב"ש, יוצר החסידות, בספרו… כנגד… לשון הרע"…אינני מתימר להיות בקי בספריו המרובים של החפץ חיים, אך לפי מיעוט ידיעתי אין הוא מזכיר בשום מקום לא מחבר חסידי***, לא ספר חסידי ולא ספור חסידי. ולו חפץ היה "לעשות צעד פייסני כזה" הרי היו לפניו הזדמנויות מרובות מלבד המעשה "בגלגול סוס". ואם לא עשה כן, ודאי טעמו ונמוקו עמו, משום שהיה "מתנגד" לחסידות. מובן, שאין בכך כדי לגרוע ח"ו מכבודו. ואף החסידים הכירו בגאונותו ובצדקתו, וספריו נתחבבו עליהם. ושלום על ישראל.ואחתום במאמרו של רב יהודה: לא חרבה ירושלים אלא בשביל שביזו בה תלמידי חכמים (שבת קיט ע"ב). יהי רצון שנזכה לנחמת ציון ובנין ירושלים.שמואל אשכנזי

* שמואלי כותב: "קונטרס 'שפת תמים' צורף לכל המהדורות הראשונות של הספר 'חפץ חיים'". ואני איני מכיר אלא מהדורה אחת בלבד שבה נספח הקונטרס לספר חפץ חיים, והיא אחרונה (23). מהדורה זו נדפסה בשם "כל ספרי המוסר על עניני שמירת הלשון, מאת רבנו רבי ישראל מאיר… הכהן".** ראיתי טופס שנשמט ממנו הקונטרס. ומן הענין להעיר, שגם מן ההוצאה השניה (תרלט) מצויים טפסים בהשמטת הקונטרס. גם בימינו נדפס ספר שמירת הלשון בלי הקונטרס, כגון: ירושלים תשיד (הוצאת הרב הרשקוביץ) ותשטז (הוצאת הועד המרכזי לשמירת הלשון).*** להוציא את רש"ז מלאדי, ש"שולחן ערוך" שלו הובא הרבה במשנה ברורה.

הערות מאת אליעזר בראדט:

א. לאחרונה ענין זה נדון על ידי ר' יהושע מונדשיין כאן וכאן.

ב. בביאור הלכה סי' רי"ד בסוף הוא הביא דברי ה'דרך פקודיך'.

ג. במשנה ברורה סי' תצד ס"ק יב לענין טעם לאכילת מאכלי חלב בשבועות הוא כתב בשם גדול אחד: "אמר טעם נכון לזה כי בעת שעמדו על הר סיני וקבלו התורה [כי בעשרת הדברות נתגלה להם עי"ז כל חלקי התורה כמו שכתב רב סעדיה גאון שבעשרת הדברות כלולה כל התורה] וירדו מן ההר לביתם לא מצאו מה לאכול תיכף כ"א מאכלי חלב כי לבשר צריך הכנה רבה לשחוט בסכין בדוק כאשר צוה ה' ולנקר חוטי החלב והדם ולהדיח ולמלוח ולבשל בכלים חדשים כי הכלים שהיו להם מקודם שבישלו בהם באותו מעל"ע נאסרו להם ע"כ בחרו להם לפי שעה מאכלי חלב ואנו עושין זכר לזה". ר' גדלי' אבערלאנדער בספרו 'מנהג אבותינו בידנו', ב, מאנסי תשסו, עמ' תרלד מביא שר' נחום גרינוואלד העיר שגדול אחד הוא ר' לוי יצחק מבארדיטשוב שדבריו בזה הובא בספר תולדות יצחק לר' יצחק מנשכיז. [על דברי ה'גדול אחד' ראה דברים חשובים אצל ר' אהרן מיאסניק, מנחת אהרן, ירושלים תשסח, עמ' קב-קו; פרדס אליעזר, עמ' רעט- רפב].

ד. בקשר לדעת החפץ חיים על חסידים וחסידות ראוי להביא דברי בנו ר' ליב בשם אביו החפץ חיים בזה:

1. בעשירות שניו לעת זקנתו היה מחשיב מאוד עדת החסידים, באמרו כי הם בזמנינו ככותל אבנים שנקרא בראנדוואנט שמעמידים בין בתי עץ, שאינה מניחה להתפשטות שריפה, ובימינו שנגף הכפירה פשטה בכל עבר ופאה, ולאלפים שהם מאמינים בד' ובתורתו אבל כמו מתביישים בקיום מצותיה, בריש גלי, בל יהא לשחוק בין הגויים, ובין פרצי עמנו שרבו המלעיגים מכל קודש, עלינו לשבח החסידים שהם אמיצי רוח, עושי דברו ביד רמה, ובפומבי, ועוד הם מגדלים בניהם לתורה ולעבודה כאבותיהם. רוממות אל בגרונם, ולשונם כחרב להשיב להחפשים אל חיקם עשרת מונים בוז וקלון,, ועל כל פשעים, תכסה אהבת ה'… (דוגמא מדרכי אבי זצ"ל, עמ' טו, אות מ).

2. זכרוני לפני שלשים שנה בערך בהתישבי בפולין והחלותי למכור ספרי מר אבי ז"ל, עיקר פדיוני היה בבתי מדרשות של החסידים, שרובי הכתות שבהם הם בני תורה, והיו לוהטים מאד לספרי מר אבי. ביחוד לספרי משנה ברורה שכפי מבטא שלהם הוא נחוץ להם כמו לחם, וכמעט כל חסיד קנה ספרינו (דוגמא מדרכי אבי זצ"ל, עמ' טז, אות מא).

3. פעם שמע שמדברים על רודת החסידות והמגרעות שיש בהם, ולא נחה דעתו, וסיפר להם מעשה איך שבימי הגאון ר' חיים מוואלזין היה בעירו בעל הבית אחד, שלמד תלמוד ואמרו עליו שחזר כבר על הש"ס כמה פעמים, והוא בקי כמעט בו, והירדו הגאון ר"ח בקימה כשנכנס, והיו אז בישיבת ר' חיים אברכים גדולי תורה, ושחקו כשקם רבם בפני הבעל הבית הלז, באמרם, בפני מי קם רבנו, אם בקי הוא במלות, אבל בכמה מקומות אינו מבין הפשט, וענה להם רבם ר"ח, יש שני שסים ש"ס אחד הוא דפוס אמשטרדם, יקר מאוד הן במראיתו הן בהגהות ותיקונים רבים שיש בו, ויש ש"ס זולצבאך, עליו אינם בהירים כל כך, גם נמצא בו שיבושים אבל אם יעלה על הדעת מי שהש"ס דזולצבאך אין לו קדושת ש"ס. כן הבעל הבית הזה, אפשר יש בתורתו איזה שיבושים אבל בעיקרו יודע הוא את הש"ס, והנמשל הוא לענין חסידים אם יש בהם איזה שגיאות, אבל בעירם הם מחזיקן בתורת ה' בכל נפשם ומגדלים את בניהם ביראת ה' ומשיאים את בנותיהם לשומרי תורה ומצוה, ומה לנו עוד" (דוגמא מדרכי אבי זצ"ל, עמ' יז-יח, אות מב).

4. דברו אתו פעם על דבר חסידים ומתנגדים, ענה ואמר, חכמינו אמרו לעתיד לבוא מבא הקב"ה ספר תורה ומניחה בחיקו ואומר מי שעסק בה יבא ויטול שכרו, הרי שאין שואלים כלל לאיזה עדה הוא שייך, אלא אם קיים התורה הרי טוב ואם לאו ח"ו, לא יועילו לו שום עדה ששייך לה, גם אח לא פדה יפדה איש (דוגמא מדרכי אבי זצ"ל, עמ' סב, אות לב).