The Date of the Exodus: A Guide to the Orthodox Perplexed

The Date of the Exodus: A Guide to the Orthodox Perplexed [1] by Mitchell First

The Exodus is arguably the fundamental event of our religion. The Sabbath is premised upon it, as are many of the other commandments and holidays. Yet if one would ask a typical observant Jew “in what century did this Exodus occur?,” most would respond with a puzzled look. The purpose of this article is to rectify this situation. Admittedly, the date of the Exodus and the identity of the relevant Pharaoh are difficult questions. The name of the Pharaoh is not provided in the Bible. One scholar has remarked:[2]

The absence of the pharaoh’s name may ultimately be for theological reasons. The Bible is not trying to answer the question “who is the pharaoh of the exodus” to satisfy the curiosity of modern historians. Rather, it was seeking to clarify for Israel who was the God of the exodus.[3]

Nevertheless, there have been some important developments in recent decades which warrant this post. Part I: The Date of the Building of Solomon’s Temple According to 1 Kings 6:1, 480 years elapsed from the Exodus to the building of the First Temple in the 4th year of the reign of Solomon.[4] This suggests that a first step towards dating the Exodus would be obtaining the BCE date for the building of the First Temple.[5] When books published by ArtScroll and other traditional Orthodox publishers provide a date for the building of the First Temple, the date they provide will usually be around 831 BCE.[6] Unfortunately, this date is far off. The date for the building is approximately 966 BCE. Why is there such a discrepancy? ArtScroll and the other traditional Orthodox publishers will provide a date around 831 BCE because that is the date for the building of the First Temple that is implied from rabbinic chronology. 831 BCE is the date that is arrived at after subtracting from 70 CE: 1) the 420 years which rabbinic chronology assigns to the Second Temple period, 2) the 70 years between the Temples, and 3) the 410 years which rabbinic chronology assigns to the First Temple period.[7] (In this calculation, one arrives at 831 BCE and not 830 BCE, because there is no year zero between 1 BCE and 1 CE.) But there are two problems with this calculation: 1. The Second Temple period spanned 589 years, not 420 years. I have addressed this extensively in my book, Jewish History in Conflict (1997), and will only touch upon it briefly here: The Tanach does not span the entire Persian period, which lasted about 207 years (539-332 BCE). Only some of the kings from the Persian period are included in Tanach.[8] The rabbinic figure of 420 years for the length of the Second Temple period probably originates with R. Yose b. Halafta of the 2nd century C.E., who was the author or final editor of Seder Olam.[9] When R. Yose had to establish a length for the Second Temple period, he did not have complete information. In assigning a length, he decided to utilize a prediction found at Daniel 9:24-27. Here, there is a prediction regarding a 490 year period, but the terminii of this 490 year period are unclear. For a variety of reasons, R. Yose decided to interpret the 490 year period as running from the destruction of the First Temple to the destruction of the Second Temple. After subtracting 70 years for the period between the Temples, he was left with only 420 years to assign to the Second Temple period. This forced him to present a chronology with a shorter Persian period than he otherwise would have.[10] (Even so, he probably did not believe that the Persian period spanned anything close to two centuries.) 2. The First Temple period spanned approximately 380 years (c. 966-586 BCE), not 410 years. The First Temple was destroyed in 586 BCE[11] (and not 421 BCE, as implied by rabbinic chronology). It was built in the 4th year of Solomon. The BCE dates for the reigns of Solomon and the other First Temple period kings can be calculated because of the interactions between some of our kings and some of the Egyptian and Assyrian kings.[12] For example, the Tanach tells us (I Kings 14:25) that king Shoshenk (=Shishak) of Egypt invaded Jerusalem in the 5th year of Rehavam. Based on Egyptian sources, this invasion can be dated to 926 or 925 BCE. Assuming we (arbitrarily) utilize the 925 BCE date and assuming that Rehavam followed an accession-year dating system,[13] this means that the year Rehavam acceeded to the throne (=the year Solomon died), would have been approximately 930 BCE. Solomon ruled into his 40th year (I Kings 11:42 and II Ch. 9:30) This means that the fourth year of his reign would have been approximately 966 BCE.[14] The Tanach nowhere states that the First Temple period spanned 410 years. If one totals the reigns of the individual kings of Judah during the First Temple period, and adds the last 37 years of the reign of Solomon, one obtains a figure of approximately 430 years.[15] The origin of the 410 year figure is somewhat of a mystery.[16] The large 430 year total is probably due to cases of co-regencies of father and son, or cases where the son ruled while the father was still alive but not functionally reigning. In these cases, the Tanach has sometimes provided the full amount of years that each king reigned, even if only nominally, despite the overlap.[17] —- Once we realize that the First Temple was built in approximately the year 966 BCE, we can date the Exodus, based on I Kings 6:1, to approximately the year 1446 BCE.[18] If so, Thutmose III (1479-1425) would be the Pharaoh of the Exodus.[19] Part II. Must We Accept the 480 Year Figure Found at I Kings 6:1?[20] Two separate questions are implied here: 1. Are we, as Orthodox Jews, required to accept this figure found in the book of Kings? 2. What evidence supports and contradicts this figure? I am not going to address the first question. This kind of question has been discussed elsewhere.[21] (My book includes much discussion of whether Orthodox Jews are required to accept the 420 year tradition for the length of the Second Temple period. But admittedly that is a different issue, because only a rabbinic tradition is involved.) As to the second question, the 480 year figure is roughly consistent with a 300 year figure utilized by Yiftah, one of the later Judges, in a message he sends to the king of Ammon (Judges 11:26):

While Israel dwelt in Heshbon and its towns, and in Aror and its towns, and in all the cities that are along by the side of the Arnon, three hundred years, why did you not recover them within that time?

But what happens when we compare the 480 figure with the data found in the books of Joshua, Judges and Samuel? The specific years mentioned in the book of Judges (8, 40, 18, 80, 20, 40, 7, 40, 3, 23, 22, 18, 6, 7, 10, 8, 40, and 20) total 410.[22] To calculate the period from the Exodus to the 4th year of Solomon, one must add to this: -40 years for the desert wandering; -a length for the period the Israelites were led by Joshua, and after his death, by the elders; [23] -a length for the judgeship of Shamgar; -40 years for the judgeship of Eli (I Sam. 4:18);[24] -a length for the judgeship of Samuel;[25] -a reasonable length for the reign of Saul;[26] -40 years for the reign of David (II Sam. 5:4-5, I Kings 2:11); and – the first 3 years of Solomon. If one does this, one arrives at a sum greater than 480 for the period from the Exodus to the 4th year of Solomon. (But to the extent that some of the numbers in the book of Judges can be viewed as overlapping,[27] the discrepancy is reduced.) The 300 year figure utilized by Yiftah can be interpreted as only an approximation. More importantly, the context of the statement suggests that it was only an exaggeration, made with the intent of strengthening the Israelite claim to the land involved. As one scholar writes (exaggeratingly!):[28]

Brave fellow that he was, Jephthah was a roughneck, an outcast, and not exactly the kind of man who would scruple first to take a Ph.D. in local chronology at some ancient university of the Yarmuk before making strident claims to the Ammonite ruler. What we have is nothing more than the report of a brave but ignorant man’s bold bluster in favor of his people, not a mathematically precise chronological datum.

The 480 figure, in its context, does sound like it was meant to be taken literally.[29] But it has been argued that it was only a later estimate based on mistaken assumptions.[30] Moreover, we have no other evidence that the Israelites in the period of the Judges and up to the time of Solomon were keeping track of how many years it had been since the Exodus. There was a time when there was significant evidence in support of a 15th century BCE Exodus. For example: ° When Yeriho was excavated in the 1930s by John Garstang, he found a city wall that he estimated to have collapsed around 1400 BCE. He also excavated an area which was destroyed in part by fire, and dated this destruction to around 1400 BCE.[31] But Kathleen Kenyon, excavating two decades later, showed that the collapsed wall was from about 1000 years earlier,[32] and that the destruction and conflagration that Garstang had dated to 1400 BCE should in fact be dated to around 1550 BCE.[33] ° The volcanic eruption that occurred long ago on the Mediterranean island of Santorini[34] might explain most of the ten plagues and the parting of the yam suf.[35] This was the second largest eruption in the past four millenia, and there is no question that it had an impact as far away as Egypt.[36] This eruption had traditionally been dated to around 1500 BCE. But recent radiocarbon and other scientific dating now strongly suggest that this eruption took place in the middle or late 17th century BCE.[37] There is much circumstantial evidence against a 15th century BCE Exodus: ° The implication of the book of Exodus is that the Israelites, in the northeastern part of Egypt, were not far from the capital.[38] But in the period from 1550- 1295 BCE, the Egyptian capital was located in a region farther south, at Thebes.[39] It was only beginning with Seti I (1294-1279) that an area in the northeastern part of Egypt began functioning as the Egyptian capital, when Seti I built a palace there.[40] ° After the Six-Day War and additional areas came under Israel’s control, Israeli archaeologists were able to study much new territory that had been part of ancient Israel. Their studies show that the period that Israelite settlements began to appear in the land was the late 13th and early 12th centuries BCE, not the 15th and 14th centuries BCE.[41] ° Scores of Egyptian sources from 1500-1200 BCE have come to light that refer to places and groups in Canaan.[42] Yet there is no reference to Israel or to any of the tribes until the Merneptah Stele from the late 13th century BCE.[43] (The Merneptah Stele will be discussed below.) ° The Philistines appear as a major enemy of Israel during the period of the Judges,[44] appearing in chapters 3, 10 and 11 of the book of Judges.[45] But they only arrived in the land of Canaan around the 8th year of Ramesses III (=1177 BCE).[46] ° Egypt is never mentioned as one of the oppressors against whom Joshua or a leader in the book of Judges fought. This would be very strange for a conquest commencing around 1400 BCE. Egypt seemed to have exerted strong control over the land of Canaan at this time and for the next 200 years.[47] Part III. Most Likely, the Relevant Pharaohs are Ramesses II (1279-1213) and Merneptah[48] (1213-1203) We have already observed that, archaeologically, the period that Israelite settlements began to appear in the land is the late 13th and early 12th centuries BCE. This suggests that we should be looking in the 13th century BCE for our Pharaoh of the Exodus. Moreover, Exodus 1:11 tells us that the Israelites built store cities (arei miskenot) called Pitom andרעמסס .[49] Since the latter is an exact match to the name of a Pharaoh, this suggests that the Pharaoh who ordered this work (=the Pharaoh of the Oppression) bore this name. No Pharaoh bore this name until the 13th century BCE. The first to do so was Ramesses I. But he only reigned sixteen months (1295-94). Thereafter, after the reign of Seti I, Ramesses II reigned for over six decades. [50] Since Ramesses I only reigned sixteen months, while Ramesses II reigned over six decades, it is much more likely that the latter is the Pharaoh we should be focusing upon. Moreover, archaeology has shown that Ramesses II was responsible for building a vast city called Pi-Ramesse, which would have required vast amounts of laborers and brick.[51] Ramesses I, on the other hand, is not known to have built any cities.[52] Exodus 2:23 tells us that the Pharaoh of the Oppression died. If Ramesses II was the Pharoah of the Oppression, the Pharaoh of the Exodus would be his successor, Merneptah.[53] But there is problem with this scenario. The Stele of Merneptah,[54] dated to his 5th year, refers to “Israel”[55] as one of the entities in the region of Canaan that Merneptah boasts of having destroyed.[56] This implies that Israel was already a significant entity in the land at this time. The pertinent section of the Stele reads: [57]

The princes lie prostrate… Not one lifts his head among the Nine Bows.[58] Destruction for Tehenu! Hatti is pacified Cannan[59] is plundered with every evil Ashkelon is taken; Gezer is captured; Yanoam is made non-existent; Israel lies desolate; its seed[60] is no more; Hurru has become a widow for To-Meri; All the lands in their entirety are at peace…[61]

If the Exodus was followed by a 40 year period of wandering in the desert, and all of the Israelites entered Israel in the same stage, it would be impossible for Merneptah to have been the Pharaoh of the Exodus, since there was already an entity called Israel in the land of Canaan in the 5th year of his reign. Of course, one approach is to view Ramesses II as both the Pharaoh of the Oppression and the Pharaoh of the Exodus, and to treat verse 2:23 as an erroneous detail that somehow made its way into our official tradition. Obviously, we would like to avoid such an approach. Interestingly, there is a rabbinic view that treats the death mentioned at 2:23 euphemistically. According to this midrashic rabbinic view, verse 2:23 did not mean that the Pharaoh died; it only meant that he became leperous.[62] Identifying the Pharaoh of the Oppression with the Pharaoh of the Exodus is at least consistent with this rabbinic view.[63] A different solution is to postulate that some Israelites never went down to Egypt, and that these are the Israelites referred to by Merneptah. Although we are not used to thinking in this manner, there is perhaps some evidence in Tanach for such an approach.[64] Other solutions view the Israelites referred to by Merneptah as Israelites who left Egypt before the enslavement began, or who were enslaved but left Egypt in an earlier wave. Rabbi J. H. Hertz took the first of these approaches, and his comments (although written in the 1930’s) bear repeating: [65]

[If the reference in the Stele is to Israelites], then it refers to the settlements in Palestine by Israelites from Egypt before the Exodus… From various notices in I Chronicles[66] we see that, during the generations preceding the Oppression, the Israelites did not remain confined to Goshen or even to Egypt proper, but spread into the southern Palestinian territory, then under Egyptian control, and even engaged in skirmishes with the Philistines. When the bulk of the nation had left Egypt and was wandering in the Wilderness, these Israelite settlers had thrown off their Egyptian allegiance. And it is these settlements which Merneptah boasts of having devastated during his Canaanite campaign. There is, therefore, no cogent reason for dissenting from the current view that the Pharaoh of the Oppression was Rameses II, with his son Merneptah as the Pharaoh of the Exodus.

—– If we view the entity “Israel” in the Stele as representing the body of Israelites who came out of Egypt in the main Exodus, the matter of the determinative sign used for “Israel” becomes significant. The name “Israel” is marked with a determinative sign that differs from the determinative sign used for all the other city-states and lands in this section. All of the others[67] are accompanied by the determinative sign for city-state/land/region, while “Israel” is accompanied by the determinative sign for “people.” This could mean that the people of Israel were viewed as having arrived in Israel only recently and as having not yet settled down. This interpretation of the sign would support the view that the Exodus occurred only shortly before the time of the Stele, i.e., in the 13th century BCE.[68] Alternatively, the sign could mean only that the people of Israel were viewed as a nomadic people, or as a people that were settled in scattered rural areas but not as a city-state.[69] The implication of the different determinative sign for “Israel” has been much debated.[70] —– A key issue that needs to be addressed is how a 13th century BCE Exodus squares with the book of Joshua and its listing of various sites in Canaan that were conquered by the Israelites. We would like to know, for each site,[71] if there is evidence of people having occupied the site in the 13th and 12th centuries BCE (so that they could have been there for the Israelites to defeat), and whether or not there is evidence of a 13th or 12th century BCE destruction at the site.[72] I cannot discuss every site included in the book of Joshua, but I will briefly discuss four of them: [73] °Hazor: The archaeological evidence indicates that there was an occupation at Hazor which was terminated by a destruction in the latter half of the 13th cent. BCE.[74] Evidence of a conflagration as part of this destruction has also been found. Joshua 11:11 had referred to a destruction by conflagration at Hazor. °Lachish: The archaeological evidence indicates that there was an occupation at Lachish which was terminated by a destruction around 1200 BCE, and an occupation which was terminated by a destruction in the reign of Ramesses III (1184-1153 BCE).[75] °Ai (= Et-Tell). The archaeological evidence indicates that this area was entirely deserted from around 2400 BCE to around 1200 BCE, when a new smaller occupation seems to have begun peacefully.[76] °Yeriho: The archaeological evidence indicates that there was a conflagration and destruction at Yeriho in approximately 1550 BCE.[77] There was minimal occupation thereafter, without any wall, in the period from about 1400-1275 BCE.[78] There is no evidence of any occupation in the period from about 1275-1100 BCE.[79] Thus, the evidence from Hazor and Lachish is consistent with a 13th century BCE Exodus, but the evidence from Ai and Yeriho is not. But Et-Tell may not have been the Biblical Ai; many other sites for Ai have been suggested.[80] With regard to Yeriho, it may have only been a small fort in the 13th century BCE, with only a minor wall,[81] and the evidence of this minor occupation and destruction may have eroded away over the centuries.[82] The book of Joshua never calls Yeriho a “large” city.[83] —- Finally, a few other matters need to be discussed in connection with attempting to identify the relevant Pharaohs as Ramesses II and Merneptah: °Exodus 7:7 records that Moses was 80 years old when he first spoke to Pharaoh. If the Pharaoh of the Oppression was Ramesses II, and Moses was born shortly after he began to reign in 1279 BCE, Ramesess II, Merneptah and Amenmesses (the subsequent Pharaoh) would all have died by the time Moses was 80.[84] (The reigns of Ramesses II, Merneptah, and Amenmesses total approximately 79 years). Yet the book of Exodus only records the death of one Pharaoh between the beginning of the Oppression and the Exodus. A response is that we do not have to make the assumption that Moses was born after Ramesses II began to reign and that Ramesses II was the Pharaoh who ordered the male infants thrown into the river. We can understand the decrees against the Israelites to have been enacted in stages by separate Pharaohs, and assume that the book of Exodus oversimplifies matters in portraying only one Pharaoh of the Oppression. The import of Exodus 1:11 can be that the Israelites eventually built or completed the store cities of Pitom and Ramesses under Ramesses II.[85] ° The 14th chapter of Exodus and Psalms 106:11 and 136:15 can be read as implying that even the Pharaoh drowned.[86] But the mummies of both Ramesses II and Merneptah (and of nearly every Pharaoh from the New Kingdom[87]) have been found,[88] and their examination suggests that Ramesses II died from old age[89] and that Merneptah died from heart trouble.[90] Moreover, if all the Egyptians at the scene drowned, it would have been unlikely that the body of a drowned Pharaoh would ever have been recovered. A response is that one can easily understand the 14th chapter of Exodus and the above verses from Psalms as not necessarily implying that the Pharaoh actually entered the water.[91] ° The fact that the book of Ruth (4:20-22) records David as being only the sixth generation from Nahshon can be reconciled with a 13th century BCE Exodus. On the other hand, the list of high priests that the Tanach provides from Aaron to the time of Solomon is longer,[92] and the geneaology of Samuel that the Tanach provides is even longer.[93] Thus, the evidence from the geneaological lists in Tanach is inconsistent. [94] Part IV. A Brief Response to “Exodus Denial” A mainstream view in scholarship today is that all or most of the Israelites originated in Canaan.[95] If a portion of the Israelites were slaves in and fled from Egypt, it is argued that they were only a small portion. “Exodus Denial” has infected the new Encyclopaedia Judaica as well.[96] The archaeological evidence for the theory that all or most of the Israelites originated in Canaan is very speculative.[97] Archaeology has been able to document a large increase in population in the central hill country of Canaan commencing at the end of the 13th century BCE,[98] and to provide grounds for identifying this new population with early Israel.[99] But determining where this increased population came from is a much more difficult task.[100] A main reason the occurrence of an Exodus is disputed is the lack of Egyptian records recording a story of an enslavement of Israelites and their flight.[101] But we do not have narrative history works from the times of the possible Pharaohs of the Exodus. Nor, with regard to the 13th century BCE Pharaohs, do we have their administrative records. As the noted Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen has remarked:

As the official thirteenth-century archives from the East Delta centers are 100 percent lost, we cannot expect to find mentions in them of the Hebrews or anybody else.[102]

In the limited 15-13th century BCE material from the Egyptian palaces and temples that has survived, there is evidence that foreign workers and captives were employed in building projects; that the supervision of the work was two-tiered;[103] that straw was used as an ingredient in the bricks; that workers were faced with brick quotas; and that workers were supervised by taskmasters threatening to beat them with rods.[104] The one thing we are lacking is a document or relief from Egypt referring to slaves or workers as “Israel.” But even though the Merneptah Stele refers to our ancestors outside the land of Egypt as “Israel”, this does not mean that Egyptians would have used this term for our ancestors as slaves inside Egypt. Levantines in Egypt would typically be described as “Asiatics” (Egyptian: ‘amw), not by specific affiliations.[105] Moreover, our ancestors may have been intermingled with native Egyptians and other foreign groups while enslaved. Leiden Papyrus 348, a decree by an official of Ramesses II, does record that grain rations were given to: “the apiru who are dragging stone to the great pylon (=gateway)” of Ramesses II.[106] There was a time when a mainstream scholarly position was that apiru was a reference to the Israelites. Now most scholars believe that the term is a general term for a class of renegades or displaced persons. As has been noted, the Biblical Hebrews (=Israelites) may have been apiru, but not all apiru were Biblical Hebrews.[107] It has often been pointed out that it is unlikely that any people would invent a tradition of slavery in another land. Moreover, references to the Exodus are numerous in Tanach.[108] Instead of looking at Egyptian history for references to the Israelite enslavement in Egypt, some scholars take a different approach to proving the enslavement. They attempt to find evidence in the Bible for knowledge of Egyptian practices and beliefs.[109] For example, all of the following suggest that there was an Israelite enslavement in Egypt: -The Biblical knowledge of the details of the slaveworking process in Egypt (e.g., two tiers of supervision, bricks from straw, and brick quotas). -The fact that some of the Biblical plagues seem to reflect a negation of Egyptian deities. -The fact that some of the Biblical stories seem to be a polemical response to Egyptian beliefs. For example, the emphasis on the hardening of the Pharaoh’s heart seems to be a response to an Egyptian belief in the lightness of an innocent heart.[110] The use of the phrase חזקה ביד seems to be a response to the use of a similar term in Egypt to describe the power of the Pharoah.[111] The story of the saving of the baby Moses is perhaps a response to an Egyptian mythical birth story involving Horus.[112] -Many words in the Bible are of Egyptian origin. I will conclude with another quote from Kitchen:[113]

The Egyptian elements suggest a direct knowledge of how Egyptian labor functioned; the magical practices and the plagues are closely tied to specially Egyptian conditions… The Exodus route via Pi-Ramesse and Succoth fits the 13th century B.C… The lack of any explicit Egyptian mention of an Exodus is of no historical import, given its unfavorable role in Egypt, and the near total loss of all relevant records in any case…The sudden increase in settlement in 12th century [BCE] Canaan is best explained by an influx of new people (not needfully a military conquest…)…That they had ultimately come from Egypt is not proven but (in light of the long and pervasive biblical tradition and good comparative data) is by far the most logical and sensible solution.[114]

End Note There are Egyptian legends from as early as the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE which refer to a mass departure of Jews from Egypt in ancient times. One could argue that these reflect independent Egyptian traditions confirming the Exodus. But more likely, these legends originated as Egyptian corruptions of an Exodus tradition that originated with the Jews, or as Egyptian polemical responses to such a tradition. I will now describe these Egyptian legends. Hecateus of Abdera, a 4th century BCE Greek historian, tells us that a pestilence arose in Egypt in ancient times. The common people ascribed it to the workings of a divine agency. The Egyptian observances had fallen into disuse due to the many strangers in their midst. To remedy the situation, the people decided to expel the foreigners. The most outstanding of the foreigners ended up in Greece; the majority of the foreigners were driven into Judea, and were led by Moses.[115] Hecateus is known to have traveled to Egypt and to have written a book about the ancient Egyptians. Most likely, he heard this story in his travels in Egypt. Manetho, a 3rd century BCE Egyptian historian, tells us two Exodus stories. The first story[116] begins with an erroneous equation of the Israelites with the Hyksos invaders.[117] Manetho reports that there was a certain shepherd-people called Hyksos who came from the east and ruled Egypt for several hundred years. Eventually, the Egyptian king Misphragmouthosis defeated them and confined them to a place called Auaris. His son, king Thoummosis (whom he later calls Tethmosis), concluded a treaty with them.[118] Under the treaty, the Hyksos were allowed to evacuate Egypt unharmed. Manetho continues:

Upon these terms no fewer than two hundred and forty thousand, entire households with their possessions, left Egypt and traversed the desert to Syria. Then, terrified by the might of the Assyrians, who at that time were masters of Asia, they built a city in the country now called Judaea, capable of accomodating their vast company, and gave it the name of Jerusalem. After the departure of the pastoral people from Egypt to Jerusalem, Tethmosis, the king who expelled them from Egypt, reigned twenty-five years and four months… [119]

The second story[120] is one which Manetho admits is less reliable.[121] In this story, the king involved is named Amenophis.[122] The following is one scholar’s summary of this story:[123]

Amenophis desired to behold the gods and received an oracle that he would attain his wish if he purified the land of lepers. The king gathered them and sent them to forced labor in the quarries, then gave them the city of Avaris as their territory, their number amounting to eighty thousand. After they had fortified themselves in Avaris, they rebelled against the king and elected a priest of Heliopolis by the name of Osarseph as their leader.[124] Osarseph commanded the lepers to cease worshipping the gods, also ordering them to slaughter and eat the sacred animals of the Egyptians. He further forbade them to associate with people not of their persuasion. He fortified Avaris with walls and sent an invitation to the descendants of the Hyksos who lived in Jerusalem to come to his aid in the conquest of Egypt. They obeyed him willingly and came to Egypt to the number of 200,000. King Amenophis fled in fear to Ethiopia, taking with him the sacred animals, and stayed there thirteen years, as long as the lepers ruled Egypt. The rule was of unparalleled cruelty; the lepers burned down towns and villages, plundered Temples, defiled the images of the gods, converted shrines into shambles and roasted the flesh of the sacred beasts. Ultimately, Amenophis gathered courage to fight the lepers, attacking them with a great host, slaying many of them and pursuing the survivors as far as the frontiers of Syria.

Select Bibliography Galpaz-Feller, Penina. Yitziat Mitzrayim: Mitziyut o Dimyon, 2002. Hasel, Michael G. “Israel in the Merneptah Stela,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 296 (1994), 45-56. Hasel, Michael G. “Merenptah’s Inscription and Reliefs and the Origin of Israel,” in Beth Albert Nakhai, ed., The Near East in the Southwest: Essays in Honor of William G. Dever, 2003, 19-44. Hess, Richard S., Gerald A. Klingbeil, and Paul J. Ray, Jr. eds. Critical Issues in Early Israelite History, 2008. Hoffmeier, James K. Israel in Egypt, 1997. Hoffmeier, James K. “What is the Biblical Date for the Exodus? A Response to Bryant Wood,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 50/2 June 2007, 225-47. Kitchen, Kenneth. “The Exodus,” in Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 2, 700-08, 1992. Kitchen, Kenneth. The Reliability of the Old Testament, 2003. Malamat, Abraham. “Let My People Go and Go and Go and Go,” Biblical Archaeological Review Jan-Feb. 1998, 62-66. Wilson, Ian. Exodus: The True Story, 1985.

[W]hen the Bible gives us technical or statistical data and the like, it frequently prefers the ascending order, since the tendency to exactness in these instances causes the smaller numbers to be given precedence and prominence.

See Cassuto, The Documentary Hypothesis and the Composition of the Pentateuch, tr. by Israel Abrahams (1961), p. 52. (Cassuto developed this theory in order to refute the view that the explanation for the different orders was a difference in sources.) The number in I Kings 6:1 is written in ascending order (80 + 400).

[T] he “Nine Bows” are the traditionally hostile neighbors of Egypt; the Tehenu are one of the Libyan peoples; Hatti is the land of the Hittites, now Asiatic Turkey; Ashkelon and Gezer are two southerly Cannanite towns; Yanoam is a town in the north of the country; Hurru , the land of the Hurrians, who are the Biblical Horites, is an Egyptian term for Palestine and Syria. To-Meri is another name for Egypt.

[I]t may be concluded that… [at the time of the Stele] the people of Israel was located in Canaan, but had not yet settled down within definable borders. Its presence there was of recent origin, so that the Exodus would have taken place in the course of the thirteenth century BCE.

See also the comments of Lawrence Schiffman in “Making the Bible Come to Life: Biblical Archaeology and the Teaching of Tanach in Jewish Schools,” Tradition 37/4 (Winter 2003), p. 48, n . 19:

The text describes the situation in Canaan in the thirteenth century B.C.E. with Israel alone pictured as a people without a geographical designation. This clearly refers to the period between the invasion and the actual settlement of the various Israelite tribes.

Those advocating an earlier date for the Exodus can make a different argument from the Stele. Since Merneptah felt that the destruction of Israel was something to boast about, Israel must have been a significant entity, one that was long-established in the land.

[O]nly four can be regarded as deficient in background finds for LB II [=Late Bronze II, c. 1350-1200 BCE] and in those cases there are factors that account for the deficiency. The rest shows very clearly that Joshua and his raiders moved among (and against) towns that existed and which in several cases exhibit destructions at this period…

Kitchen’s four deficient sites were: Makkedah, Yeriho, Ai, and Givon, and his suggested explanations were: erosion (Yeriho), wrong site (Ai), and most of the site still undug (Makkedah and Givon). Most scholars who have analyzed the sites listed as conquered in the book of Joshua have come out to more critical conclusions. See, e.g., Dever, pp. 54-72.

[C]onstruction at Tell el-Dab‘a-Qantir is now documented under the previous reigns of Horemheb (1323-1295 BC) and Seti I (1294-1279) BC. This means that the oppression of the Hebrews could have begun decades before the reign of Ramesses II and culminated with the construction of Pi-Ramesses.

The construction by Horemhab involved renovations at the Temple of Seth and enlargement of a fortress. Kitchen, On the Reliability, p. 309, Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt, p. 123, and Bietak, p. 10.

The discussion of the Exodus is connected with the Israelite Conquest of Canaan. Both of these events are not historical… Truth to tell, there was never any external evidence for the enslavement in Egypt and the subsequent exodus. Those scholars who supported some version of the enslavement tradition argued, irrelevantly, that no one would have made up a tale of enslavement, and that the tradition was persistent… The general consensus at present is that the people Israel arose in the land itself or perhaps from an area slightly to the east, with no indication of an Egyptian cultural past… [T]he tradition that the people of Israel originated outside the land serves to distance Israel from peoples to whom [they] were ethnically quite close…

The view that the Israelites obtained possession of Canaan mainly through a military conquest at the time of Joshua has also come under much attack in recent decades. The general consensus at present is that the settlement process was largely a peaceful infiltration into areas that had not been settled by the Canaanites. This rejection of the Conquest model contributes to Exodus denial, as many argue that if there was no Conquest, there was probably no Exodus. But the Exodus and Conquest are not dependent on one another. One can easily take the approach that most of the Israelites arrived in Canaan subsequent to an Exodus from Egypt but that the book of Joshua overdramatizes what happened thereafter.

This extraordinary increase in population in Iron I cannot be explained only by natural population growth of the few Late Bronze Age city-states in the region: there must have been a major influx of people into the highlands in the twelfth and eleventh centuries BCE….That many of these villages belonged to premonarchic Israel…is beyond doubt.

(Iron I is the period c. 1200-1000 BCE. The Late Bronze Age is the period c. 1550/1500-1200 BCE.) Kitchen jokingly suggests that if we do not accept an outside origin for the Israelites, the only other explanation for the huge population growth in highland Canaan between 1250/1200 and 1150 BCE is “a half century of fertility cult sex orgies.” See On the Reliability, pp. 226-27.

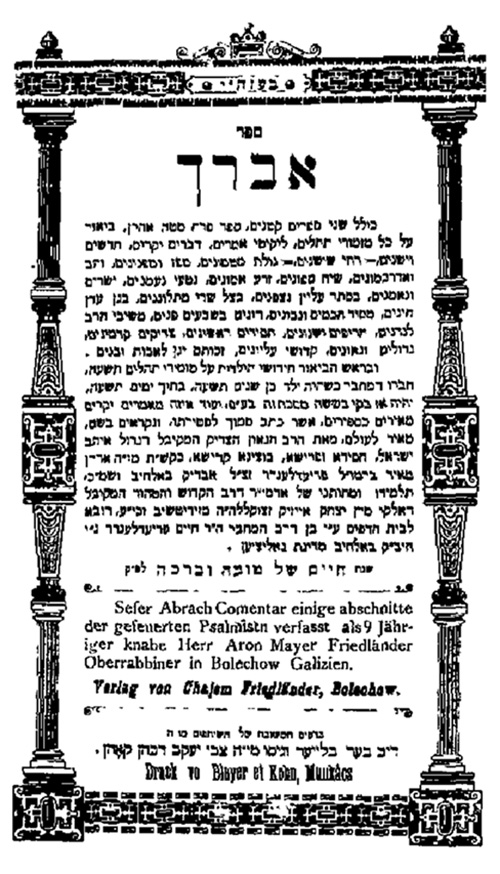

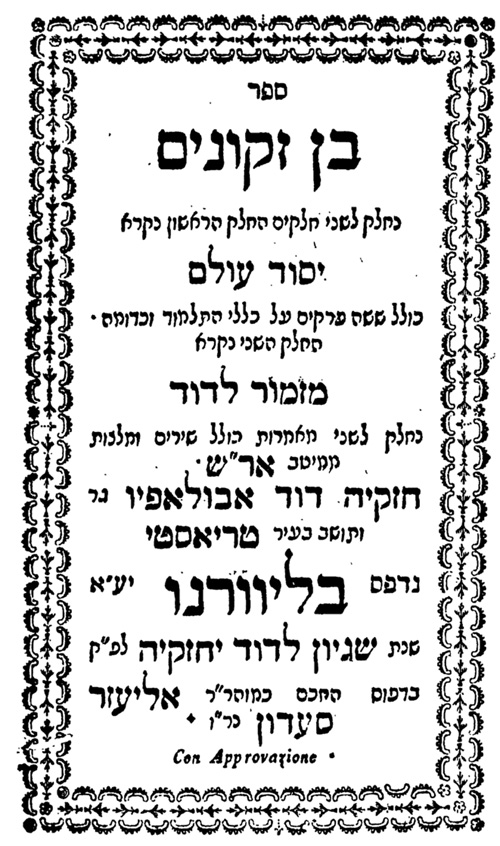

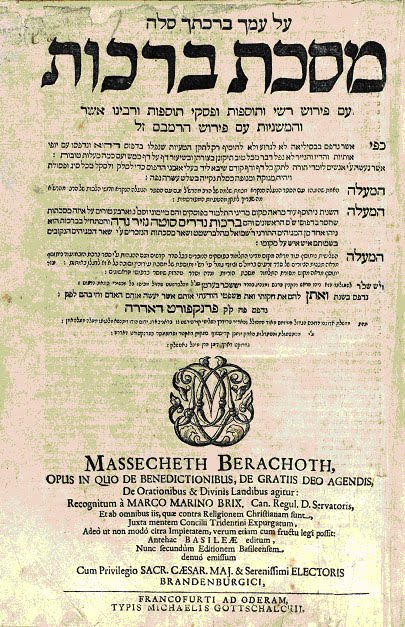

(This scan and those following are all courtesy of the JTS Library)

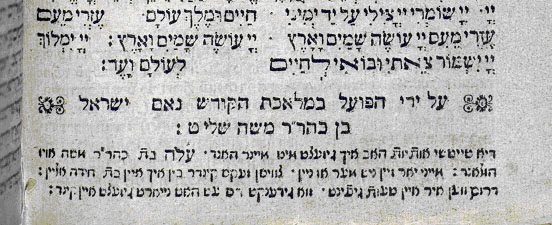

(This scan and those following are all courtesy of the JTS Library) The Berman Shas is one of the most respected early printed editions of the Talmud because it contained many additional commentaries which became standard in following editions. It was the first edition since that of Gershom Soncino in the early 16th century to contain most of the diagrams we are familiar in Seder Zeraim, and Masechtos Eiruvin and Sukah. (5) It was also the first to contain Charamos from various Rabbanim prohibiting others in that general area from printing the Talmud for an extended period of time.(6) The following Cherem, recorded in Maseches Brachos, was written by Rav Dovid Oppenheim who lived at that time in Nikolsburg and later became chief Rabbi of Prague:

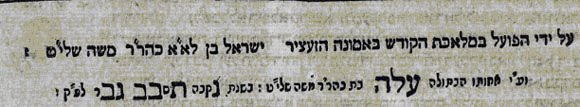

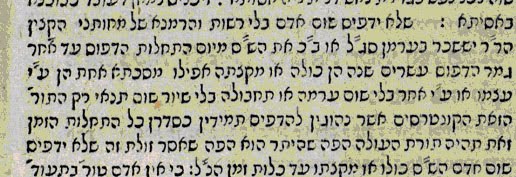

The Berman Shas is one of the most respected early printed editions of the Talmud because it contained many additional commentaries which became standard in following editions. It was the first edition since that of Gershom Soncino in the early 16th century to contain most of the diagrams we are familiar in Seder Zeraim, and Masechtos Eiruvin and Sukah. (5) It was also the first to contain Charamos from various Rabbanim prohibiting others in that general area from printing the Talmud for an extended period of time.(6) The following Cherem, recorded in Maseches Brachos, was written by Rav Dovid Oppenheim who lived at that time in Nikolsburg and later became chief Rabbi of Prague: At the end of Maseches Nidah printed in 1699, Elle signs her work a bit more boldly, and leaves us wondering what was going through her mind when she set the letters for the colophon.

At the end of Maseches Nidah printed in 1699, Elle signs her work a bit more boldly, and leaves us wondering what was going through her mind when she set the letters for the colophon.