The Legend of R. Yehuda Halevi’s Death: Truth or Fiction & the Cairo Genizahby Eliezer Brodt

A few years ago on the Seforim Blog I dealt with the famous legend of R. Yehuda Halevi’s death (link). More recently in Ami Magazine (# 32) I returned to this legend and related topics. This post contains new information as well as corrections that were not included in those earlier articles.

R. Yehuda Halevi was born in the year 1075 in Toledo, Spain, and died in 1141.[1] He is famous in Jewish history for being a great paytan,[2] authoring hundreds of beautiful piyutim. However, he is even more famous for authoring one of the most important Jewish philosophical works of all time, the Kuzari. This work is written in dialog form between a king and a Jew who is persuaded to convert to Judaism. The Jew defends Yiddishkeit, dealing with many issues of philosophy and various Mitzvos among other topics. This work was written by R. Yehuda in Arabic, but was translated into Hebrew in 1167. It was learned by many throughout the centuries, and numerous works were written to explain it.[3] The Kuzari had a tremendous impact on Jewish thought through the centuries and continues to do so today. In this article, I hope to deal with two legends told about R. Yehuda Halevi: one about how he met an untimely death when he got toEretz Yisroel [4] and the other about him being the father-in-law of Ibn Ezra.

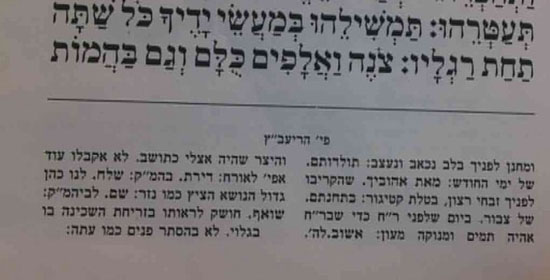

Among the more famous kinos that we recite on Tisha B’Av is Tzion Halo Tishali. This piyut is about the author’s passion to walk on the holy soil of Eretz Yisrael and to pray at the Kevarim. Throughout the Kuzari and in many of his piyutim we find a strong emphasis of his love for Eretz Yisroel[5]. R’ Yosef Dov Soleveitchik, when talking about R’ Yehuda Halevi in his lectures on the Kinos, said “Rabbi Yehuda Halevi adored everything about Eretz Yisroel; he was madly in love with Eretz Yisroel. I have never known anyone so in love with Eretz Yisroel as Rabbi Yehuda Halevi. There were many others who went to Eretz Yisroel, but they did not confess their love for the land in such terms as he did”.[6]

Already in the Machzor from Worms written in 1272 and in the Nuremburg Machzor written in 1331 we find this kinah was said on Tisha Bav. The piyut, however has become famous for a different reason.[7]

In the Artscroll commentary on the Kinos, R. Avraham Chaim Feuer writes:

An ancient manuscript states that R. Yehuda Halevi composed this kina while journeying towards Eretz Yisroel and recited it when he reached Damascus, facing the direction of Zion. Although many historians believe that R. Yehuda Halevi only got as far as Egypt, never even reaching Damascus, tradition has it that he finally reached Jerusalem (circa 1145).[8] There he fell to the ground in a state of ecstasy… As he was embracing the dust near the temple mount, he was trampled and killed by an Arab horseman.[9]

R’ Yosef Dov Soleveitchik, when talking about R’ Yehuda Halevi in his lectures on the kinos, said,

“While we know that he left for Eretz Yisroel, we know nothing about him from the date of his departure from Egypt. A story is told, I do not know if it’s true, that when he arrived in Eretz Yisroel, he fell on the soil… at that very moment a Bedouin on a horse rode over him and killed him. Now they say there is documentary evidence that he died in Egypt on his way to Eretz Yisroel. I do not know about it.”[10]

The story has certainly entered Jewish popular culture. In 1851 Heinrich Heine published his Romanzero, and in the section of ‘Hebrew Melodies’ he writes of “Jehuda ben Halevy’s” death at the hands of an “impious Saracen” horseman:

Calmly flow’d the Rabbi’s life-blood,

Calmly to its termination

Sang he his sweet song.—his dying

Sigh was still—Jerusalem!

In this article I intend to discuss this legend of R. Yehuda Halevi’s death. Did he actually reach Eretz Yisrael? When did he compose the piyut of Zion Haloeh Tishali? Why did he want to go to Eretz Yisroel so badly, considering that it was very dangerous in his time?

By the way of introduction, it is worth noting the words of R’ Elazar Ezkiri in his classic work Sefer Chareidim. He says that everyone is supposed to love Eretz Yisroel and go there… therefore the Amoraim would kiss the ground when they came,[11] and it’s good to recite the piyut Shir Yedidus composed by R’ Yehuda Halevi . . . [12] Apparently Rav Yehuda Halevi is considered a first stop for expressing such affection.

R. Abraham Zacuto (1452-1514) in Sefer Yuchsin (first printed in 1566) writes that “R. Yehuda Halevi was fifty [years old] when he came to Eretz Yisroel and he is buried together with his first cousin, Ibn Ezra.”[13] Later, however, R. Zacuto writes that R. Yehuda Halevi is buried with R. Yehuda bar Ilay in Tzefat.[14] Setting aside the apparent contradiction regarding R. Yehuda Halevi’s burial place, in both of these descriptions R. Yehuda Halevi is depicted as having actually made it to Eretz Yisrael. Notably absent, however, is the legend of an Arab/Bedouin horseman killing him.

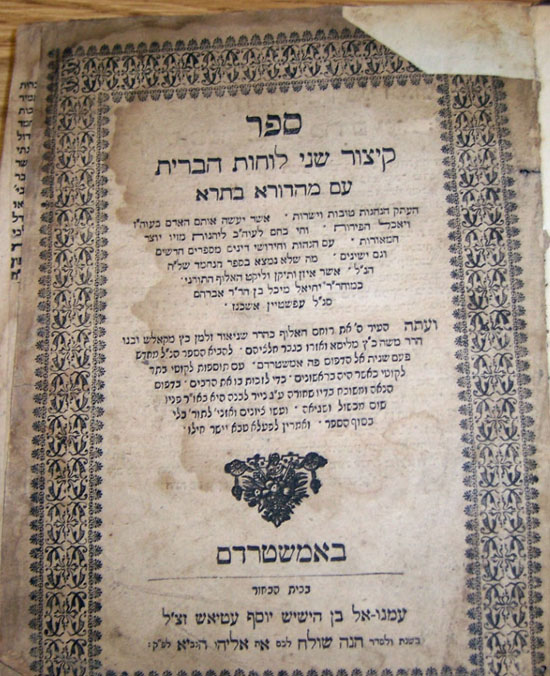

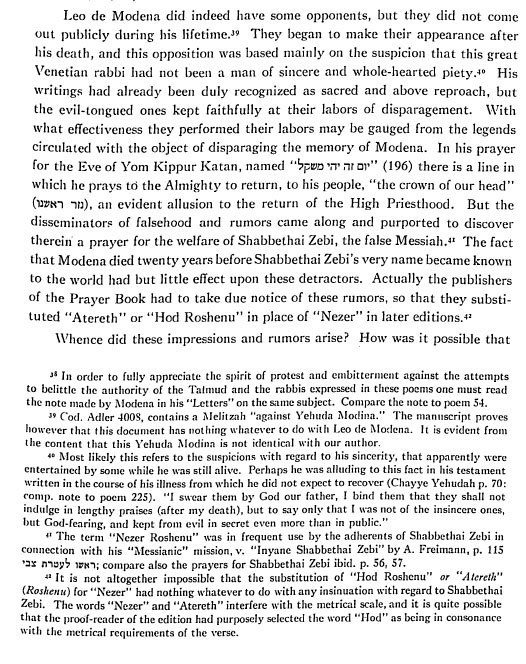

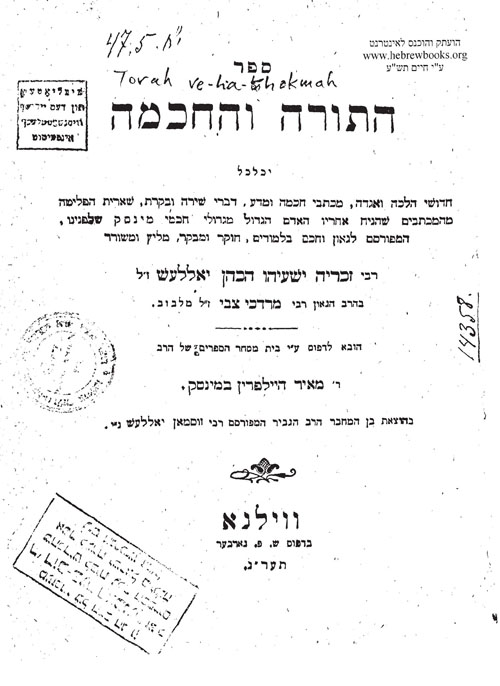

The earliest source for the Arab horseman legend only appears in R. Gedaliah Ibn Yachia’s

Shalsheles Hakabbalah, first published in Venice in 1587, over four hundred years after R. Yehuda Halevi died. He states that he heard this legend from “an old man”.

[15] Although the

Shalsheles Hakabbalah appears to be the source for R. Feuer’s statement above, the

Shalsheles Hakabbalah has one addition to the legend — omitted by R. Feuer — that R. Yehuda Halevi recited the

kinah of

Zion Halo Tishali right before the Arab horseman killed him.

[16]

The next time that this legend appeared in print, after its mention in the

Shalsheles Hakabbalah, is by R. David Conforte (1618-1678) in his

Koreh Hadoros (first printed in Venice, 1746),

[17] followed by R. Yechiel Halperin (1660- 1749) in

Seder Hadoros (first printed in Karlsruhe, 1769).

[18] It was then repeated by R. Wolf Heidenheim in his edition of the

Kinos. R. Yehosef Schwartz (1804-1865) in his

Tevous Haaretz also brings this legend.

[19] By the 19th century, this legend became, perhaps, the most famous story about R. Yehuda Halevi, since not much else was known about him.

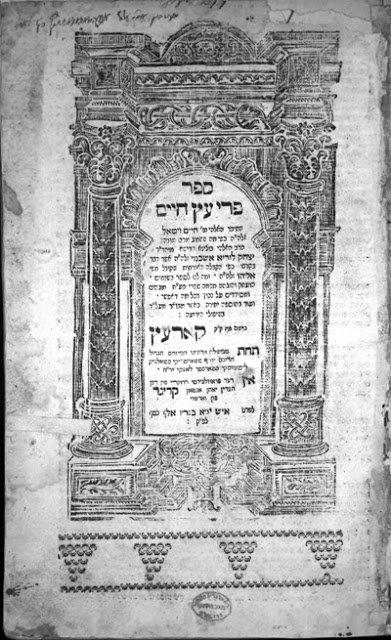

Adam Shear called attention to an edition of the Kuzari printed in 1547 which says on the front page:כוזרי חברו בלשון ערבי החכם הגדול אבי כל המשוררים רבי יהודה הלוי הספרדי ז”ל אשר קדש שם שמים בויכוחו הישר הזה… (ראה: ארשת א, עמ’ 67).

This term is usually used for martyrdom. Shear suggests that perhaps it comes from this story, later mentioned by the Shalsheles Hakabbalah,[20] although he concludes that the idea is far-fetched.

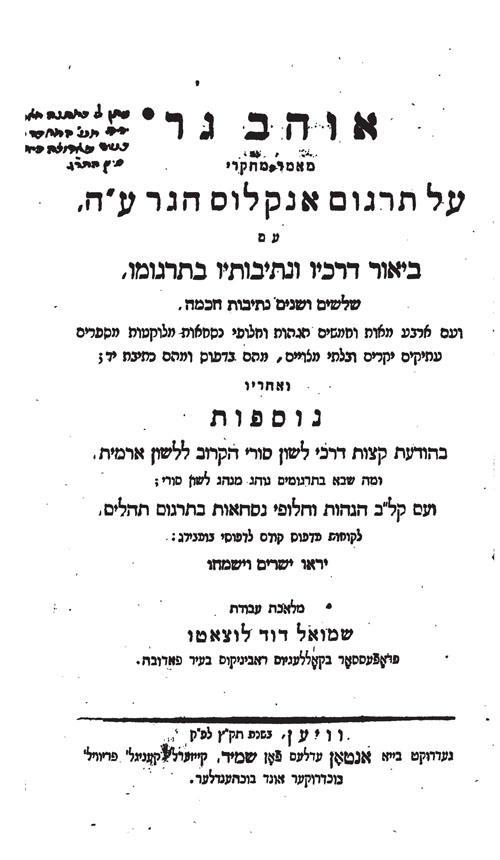

In 1840 R. Shmuel David Luzzatto (ShaDaL) in his collection of the Diwan containing the poems of R. Yehuda Halevi, Besulas Bas Yehuda, questions the legend on the grounds that Jerusalem was in the hand of Christians at the time, and Arabs were not allowed in the city. Furthermore, even if there were Arabs around, they would not have done such a brazen act right at the city gate.[21] So Shadal concludes that he died on his way from Egypt, never even reaching Eretz Yisroel.[22] S. Fuenn accepts the conclusion of Shadal.[23] R. Michael Sachs in his work Die religiöse Poesie der Juden in Spanien also accepts Shadal’s conclusion because he notes that while Ibn Ezra refers to him in his work on Chumash he does not mention anything unique about his death,[24] he just says שאלני ר’ יהודה הלוי מנוחתו כבוד.Around the same time R. Matisyahu Strashun reached the same conclusion, perhaps independently. In a letter written in 1841, he questioned the veracity of the legend,[25] alsopointing out that Jerusalem in the times of R. Yehuda Halevi was ruled by Christians and not by Arabs. R. Strashun allows that although it is possible that R. Yehuda Halevi composed Zion Halo Tishali when he got to Jerusalem — not that we know that he did — the part of the story about the Arab killing him is certainly not true. As a general matter, R. Strashun notes that it is well known that the Shalsheles Hakabbalah is an unreliable source.[26]Simon Dubnov suggests that there is a kernel of truth to the story –that some Crusader must have killed a Jew right after he arrived in Eretz Yisroel.[27]Israel Zinberg suggests that, most likely, R. Yehuda Halevi returned home to Spain after visiting Eretz Yisrael, based on the fact that R. Shlomo Parchon, a student of R. Yehuda Halevi who lived in Spain, quotes a statement from R. Yehuda Halevi “after R. Yehuda Halevi was in Egypt”.[28]Specifically, R. Yehuda Halevi had told Parchon that he was doing teshuva and therefore no longer composing.[29] Zinberg therefore argues that this statement to Parchon must have taken place after R. Yehuda Halevi was in Egypt; thus R. Yehuda Halevi must have returned to Spain.[30] David Kaufmann also used R. Shlomo Parchon as a source to deduce how R. Yehuda Halevi died. Kaufmann points out that had R. Yehuda Halevi died in such a spectacular fashion as the legend has it, R. Shlomo Parchon would have been sure to note it. Since R. Parchon makes no note of this extraordinary death, R. Yehuda Halevi must have died a natural death.[31] InAmudei Avodah, Landshuth also questions the legend due to lack of evidence that R. Yehuda Halevi ever made it to Eretz Yisrael.[32]

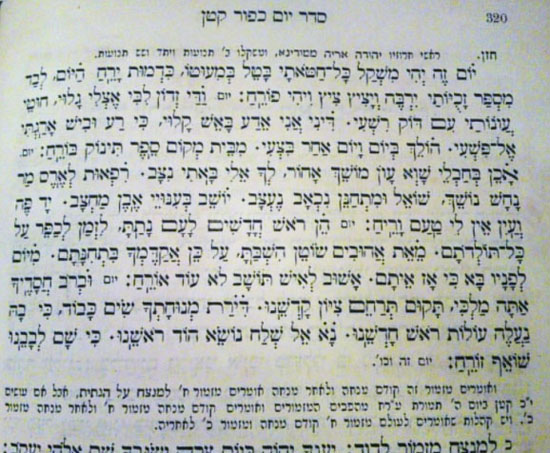

In regard to the piyut, Zion Haloh Tishali, Leser Landshuth cites different opinions about where it was written: either in Spain, Damascus, or Syria.[33] Yitzhak Baer[34] and David Kaufmann cite a manuscript housed at Oxford which says that R. Yehuda Halevi said this piyut when he got to Yerushalayim.[35]

Earlier I mentioned that the Sefer Yuchasin writes that R. Yehuda Halevi was fifty years old when he came to Eretz Yisrael, and he is buried with his first cousin, Abraham Ibn Ezra. Later he writes that he is buried with R. Yehuda bar Ilay in Tzefas. In the Travels of R. Benyamin of Tudela, written around the year 1170, which is only thirty years after the R. Yehuda Halevi died, R. Benjamin records that he visited the grave of R. Yehuda Halevi in Tiveriah.[36] It’s interesting to note that in the travels of R. Pesachya of Regensburg which were written right after R. Benyamin of Tudela’s (around 1180) there is no mention of the grave of R. Yehuda Halevi.[37]

In the travels of R. Yitzchak ben Alfurah, written around 1441, he also writes that he visited the graves of Ibn Ezra and R. Yehuda Halevi.[38] In a different anonymous list of Kevarim in Eretz Yisroel from the fifteenth century, recently printed from manuscripts from the Ginsburg Collection, it also records that Ibn Ezra and R. Yehuda Halevi are buried next to each other.[39]All of these sources provide strong evidence that R. Yehuda Halevi actually made it to Eretz Yisrael. Nevertheless, an anonymous traveler in 1473[40] and R. Yosef Sofer in 1762 write that they visited the grave of Ibn Ezra but make no mention that R. Yehuda Halevi is buried there as well.[41] In the travels of R. Moshe Yerushalmi from 1769, he writes that he visited the graves of Ibn Ezra and R. Shlomo Ibn Gabirol , but no mention is made of the grave of R. Yehuda Halevi.[42] A manuscript from the author of the Koreh Hadoros, seems to indicate that R. Yehuda Halevi was buried in Jerusalem.[43] It should of course be noted that the location of Ibn Ezra’s death in Eretz Yisroel is itself problematic. Although Sefer Yuchasin brings the opinions that he is buried in Eretz Yisroel, he initially states that he died in Calahorra, Spain. Furthermore, Rabbi Moshe of Taku – an earlier source than Sefer Yuchasin – writes of a legend told to him by Jews of England that Ibn Ezra died there, after encountering a number of sheidimwhich appeared to him as black dogs.

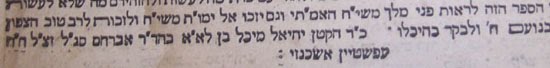

Another piece of evidence can be found inn some early manuscripts, where we find before the kinah the following superscription:

זאת הקינה יסד ר’ יהודה קשטלין לפני הר ציון

But even more than that Rabbi Holzer discovered in a manuscript written before 1300 (which he is preparing for print) , which has the following statement:

יסוד רבינו יהודה הלוי הקשטלין אשר יסדה תחת הר ציון בבואו לירושלים עם המלך מספרד וראה הר ציון שמ(ו)[ם] נשא את קולו ובכה על חורבנו ואמר ציון הלא תשאל

See The Rav Thinking Aloud, p. 222. I would like to thank Zecharia Holzer for bringing this source to my attention. What is important about these sources is that they are before theShalsheles Hakabbalah.

To sum up, there are early sources which imply that R. Yehuda Halevi did indeed arrive in Jerusalem. But with regard to the legend that he was trampled at the gates as soon as he got there, it is much more questionable.

Over one hundred years ago the Cairo Genizah was discovered and collected from an attic of the

Ben Ezra shul. Due to this incredible find, every area of Jewish literature and history has been greatly enriched.

[44] Just to list some of the many areas that were enhanced by this discovery: many works of the Geonim and manuscripts related to the Rambam were found

[45] as well as

piyutim of great people. Knowledge of Jewish history, especially from the time period of the Geonim

[46] and onwards was greatly improved by this discovery. Additionally, many years after the Cairo Genizah was originally found and its great treasures published, even more discoveries were made based on documents that were supposed to have been discarded since they were thought to have no value. Many of these later discoveries were made by the great Genizah scholar Shlomo D. Goitein. Starting in 1954, Goitein printed his discoveries with his explanations of the material in various journals and then later on, in his classic series

A Mediterranean Society which documents in great detail every aspect of Jewish life based on those finds.

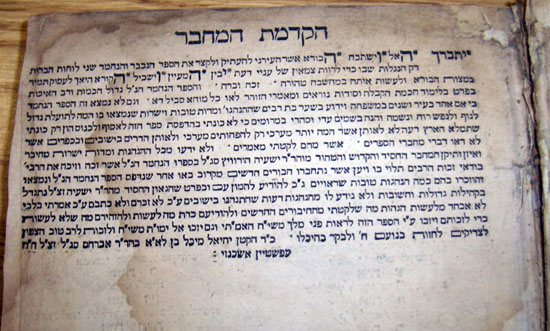

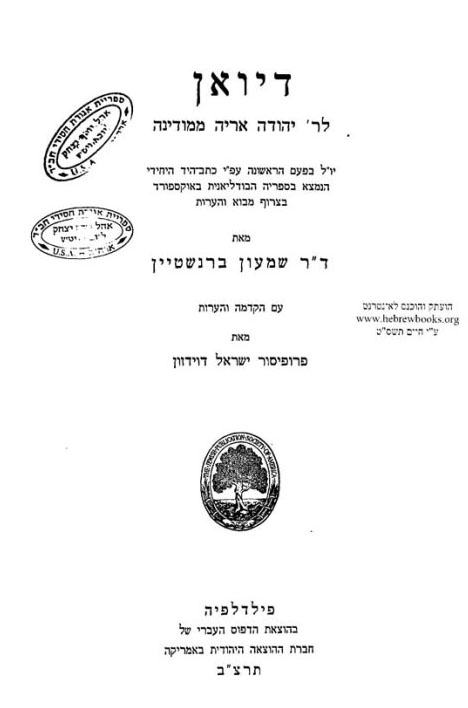

One area that benefited greatly from the later discoveries of Goitein was the history of R. Yehuda Halevi. Before this discovery, the biography of R. Yehuda Halevi was written by the early scholars of Jewish history such as Shadal[47], David Kauffman, Chaim Schirmann and many others. Their work was based heavily on the poems of R. Yehuda Halevi, for this was just about the only source. These poems existed in many manuscript collections. For example, R. David Conforte (1618-1678) in his Koreh Hadoros mentions seeing one such collection.[48] Before the aforementioned discoveries, all that was known about R. Yehuda Halevi was that he was a great poet, a medical doctor,[49] and an Askan. He was possibly a talmid of the Rif[50]and was certainly close with the Ri Migash, and may have even been his secretary for a short time.[51]And of course, in addition to his piyutim he was most famous for his important work of Jewish thought, the Kuzari.

However, among the Genizah discards Shlomo D. Goitein found many documents relating to R. Yehuda Halevi, all written around 1130-1141, including many in R. Yehuda Halevi’s own handwriting! Many of these documents can be viewed online today. Starting in 1954, Goitein printed his discoveries with his explanations of the material, in various journals, mostly inTarbitz. Later on, in his classic multi-volume A Mediterranean Society (volume V, pp. 448-468), he included an excellent chapter on R. Yehuda Halevi based on all the material which he had found over the years. Most of his interpretations of the material he discovered have been accepted by Professors C. Schirmann and Ezra Fleischer, renowned experts on Piyut.

In

A Mediterranean Society, Goitein writes, “a full publication of all the geniza letters referring to Judah Halevi would fill a book.”

[52] Although Goitein never got around to writing that book, in 2001, Professors Moshe Gil and Ezra Fleischer did write such a book. The title of the book is

Yehuda Halevei U’vnei Chugo, and it is a six hundred and forty page study of all the material from the genizah discovered by Goitein relating to R. Yehuda Halevi. This book includes all the original documents (55!) with notes and an in-depth history of all that can be gleaned from these letters. The discoveries of Goitein, followed by Gil and Fleischer are simply astounding.

For the purposes of this article, we will focus on discoveries related to R. Yehuda Halevi’s journey to Eretz Yisrael

[53]. The relevant documents were written by a Cairo business man named Abu Said Halfon who was a very close friend of R. Yehuda Halevi. I should mention at the outset, that we have more in depth information of R. Yehuda Halevi’s last year of his life from these letters than we have of the rest of his life. It is also incredible to see from these letters how popular R. Yehuda Halevi was and how beloved he was by everyone.

[54] This was before the Kuzari was widely read and learned, since R. Yehuda Halevi had just completed this work right at that time. A description of him from the letters reads, “God has been beneficent to you and sent you the quintessence and embodiment of our country our refuge and leader the illustrious scholar and unique and perfect devotee rabbi Judah the son of Halevi”.

[55]What follows is a brief time-line of R. Yehuda Halevi’s journey to Eretz Yisrael based on the research of the aforementioned professors.[56] In 1129, when R. Yehuda Halevi was fifty four years old, he decided to make the journey to Eretz Yisrael. In the year 1130, R. Yehuda Halevi began his journey. He intended to travel through Egypt. We don’t know why he didn’t. But we do know that he ended up in North Africa. In North Africa, he became good friends with Ibn Ezra. For some unknown reason, he ended up back in Spain.[57] Not too much information is known about why this journey to Eretz Yisrael did not end up happening. Ten years later, in 1140, R. Yehuda Halevi began the journey again. He ended up in Alexandria on September 8. He had intended to leave from Egypt to Eretz Yisrael immediately, but was delayed. He ended up staying in Cairo until Pesach. After that he returned to Alexandria. A few days before Shavuos of 1141, he boarded the boat, and on Shavuos, he set sail to Eretz Yisrael.[58] A letter written about 6 months later indicates that R. Yehuda Halevi was no longer alive. It seems that he was alive for 2 months in Eretz Yisrael and that he died in either Tammuz or Av.[59] We don’t have any information about his stay in Eretz Yisrael. It would seem that either he got sick or died a natural death. From the documents there is no clear answer as to whether the legend is true or not (except by omission). It’s rather disappointing that with all the manuscripts discovered in the Cairo Geniza that enriched us with an in-depth, heavily detailed history of R. Yehuda Halevi’s last years until he left to Eretz Yisrael, we do not know anything more, but of course the documents could not refer to the unnatural death if that had not happened or been dreamed of yet.

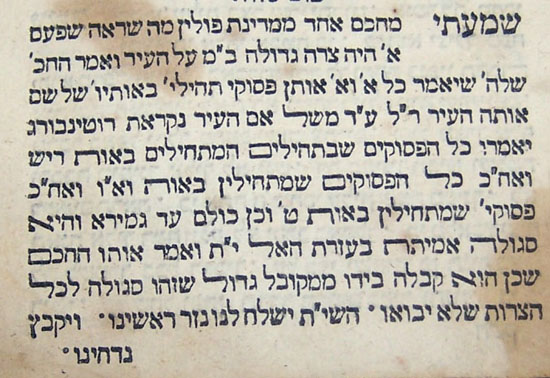

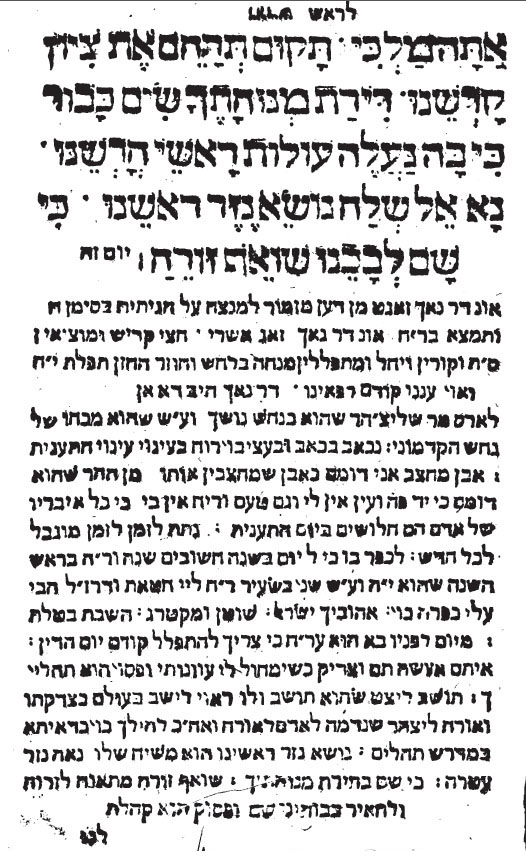

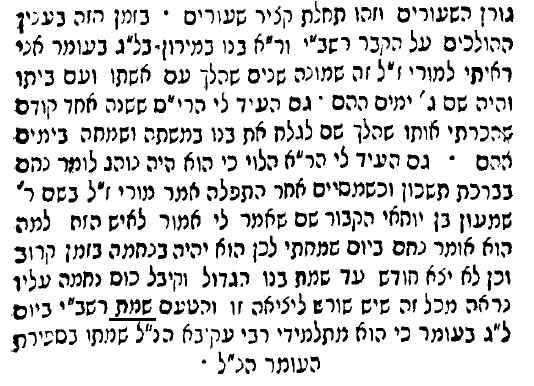

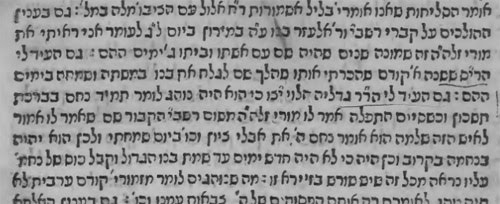

However, there is one letter written three months after the death of R. Yehuda Halevi that does seem to indicate that perhaps the legend is true. The letter reads as follows (the ellipses appear in the original):

ולא נעלם ממנה אודות רבינו יהודה הלוי הצדיק החסיד זק”ל אשר עליו באמת ניבאו נביאי האמת עין לא ראתה, ההיה גבור ביראת אלהים ובתורתו, ומאמרי פעליו מעידים צדקו, באודותיו ירונו כצפורים בעתותן למנוחת עולם הוטע כבוד גן אלהים, וברמה הוא נשא נס גדולותיו והליכות גבורותיו, אשר תרונה ביקרו, והתיקר… וביקרו, ותמונת ה’ הביט… בשדה צען להאירה… זק”ל לא… צור… מחנה שדי… להתנחל לרשת… עזי…וישם… בדמות השכינה ובמראה… בשערי ירושלים

This letter was first printed by Jacob Mann in 1920 but he dismissed the possibility that it was referring to the author of the Kuzari.[60] Goitein highlights the line “ולא נעלם ממנה אודות רבינו יהודה הלוי הצדיק החסיד זק”ל,” which would seem to indicate that his death was not natural (calling him a kadosh is typically reserved for martyrs). Note that the last words, בשערי ירושלים, would seem to support the legend. However, the letter is damaged and hard to read so one cannot say anything conclusively. However Fleischer is willing to use the letter, even with its missing parts, to support the legend. Especially since, he says, the author of the letter used the word קדוש twice in the phrase זק”ל instead of the usual ז”ל. He also has other proofs from a careful reading of the letter. Fleischer concludes from this that the legend about R. Yehuda Halevi’s death is not so far-fetched. In light of this possibility, Fleisher notes, that one should be careful not to make fun of legends.[61] Additionally ,there is also another letter in this collection that refers to R. Yehuda Halevi as a kadosh.[62]

We have shown, in light of the documents discovered in the Cario Genizah that R. Yehuda Halevi did indeed make it to Eretz Yisroel. And it would seem that there is also a good chance that the story that the Shalsheles Hakabbalah brings is true, and that he died a strange death through unnatural causes. The question remains as to why he decided to go to Eretz Yisroel at that time.[63] There were no real communities of any sort there, traveling was dangerous, and he was an older man. It is clear from many of his poems and especially from specific passages that he had a tremendous love for Eretz Yisroel. Professor Elchanan Reiner notes that he was one of the first known people that actually made the dangerous voyage to Eretz Yisroel in the times of the Rishonim. Reiner says that it was due to his strong desire to daven there, especially at various Kevarim.[64] There is strong support for this, especially in his kina Zion Halo Tishali,where he mentions this desire to daven at the kevarim. Ezra Fleischer suggests that R. Yehuda Halevi thought others would follow him to Eretz Yisroel.[65]

Goitein writes: “one might argue that the themes of Israel’s uniqueness, of the holiness of Palestine… are overdone in the Kuzari and in Ha-levi’s poetry. They are but for good reasons. It was a time of extreme urgency. Constant and gruesome warfare was going on in Spain. As Judah Ha-Levi emphasizes in his poems, whenever Christians and Muslims fought each other, the Jews were affected most by the disturbance of peace. The feeling of impotence in the absence of any signs of relief was dangerous forebodings of despair and loss of faith… All in all, the voice of encouragement ringing out from Ha-levi’s poems was stronger than whimpers of despair.”[66]

Rabbi Yehuda Leib Gerst, without seeing what Goitein wrote, suggested that since this was a time that Jews were downhearted, especially about Eretz Yisroel, he wanted to reawaken love for Eretz Yisroel. Even though it was dangerous to go at that time and it seems that many tried to convince him not to go, he still gave up everything: family, friends and a comfortable life style. He writes that even if the story of the Shalsheles Hakabbalah did not happen exactly as he heard it, his trip to Eretz Yisroel still caused a tremendous Kiddush Hashem.[67]

Although R. Yehuda Halevi’s trip did increase the Jewish people’s hope and did increase its emphasis on Eretz Yisrael, it is not clear that this was his own personal intention for going. In one of the letters discovered in the Geniza, it sounds as if he wanted to go quietly. He knew his days were numbered and he wanted to be in Eretz Yisrael alone.[68]

There is one last point worth mentioning: R’ Shlomo Yosef Zevin wrote a beautiful piece that shows that in addition to the Kuzari being a philosophical work, it also has many halachic aspects and was accordingly used by many.[69] One recent example is in the famous controversy between the Chazon Ish and many other gedolim regarding the placement of the International Dateline – specifically regarding which day the bochurim of the Mir yeshiva should celebrate Yom Kippur in Japan. One of the main sources on the topic of the Chazon Ish was the Kuzari.[70]Regarding the halachic aspect of going to Eretz Yisroel, the Kuzari writes that it is a Mitzvah even nowadays, making him one of the earliest sources to say such a thing. Even more importantly, he says one should go even if it’s dangerous.[71] In this light, it is evident why he made this trip: he held that he was halachically obligated to even though it was dangerous![72]

I would like to conclude with one last point that is related to all this. I mentioned earlier that R. Abraham Zacuto in Sefer Yuchasin writes that “R. Yehuda Halevi was fifty [years old] when he came to Eretz Yisroel and he is buried together with his first cousin, Ibn Ezra.[73] Now we know that there was certainly a strong connection between Ibn Ezra and R. Yehuda Halevi. D. Kaufmann gives a listing of the many times which Ibn Ezra quotes R. Yehuda Halevi throughout his works.[74] In addition, there are many other places in his works which clearly indicate that R. Yehuda Halevi had a great influence on his works.

R. Azariah de Rossi, in his Me’or Eynaim, writes that R. Yehuda Halevi was Ibn Ezra’s father-in-law (chapter 42). Koreh hadoros also brings this down. R. Immanuel Aboab in his Bemavak ‘al Erko shel Torah, written in 1615, claims that Ibn Ezra was both R. Yehuda Halevi’s son-in-law as well as a cousin.[75]

The Shalsheles Hakabblah brings a legend which he had heard about how exactly Ibn Ezra became the son-in-law of R Yehuda Halevi.[76] The gist of the story was that R. Yehuda Halevi was working on a poem and he got stuck. He left his notebook open and went away, and when he returned, he found the poem completed. It turned out that Ibn Ezra had completed it, and because of this, R. Yehuda Halevi let him marry his only daughter. There are many versions of this story, but strangely, if this were true, in the many times that Ibn Ezra quotes the Kuzari in his works, he never once refers to him as his father-in-law.[77]

R. Yehuda Al-charizi writes in his Sefer Tachkemoni, (written between 1195-1234) that Ibn Ezra had a son Yitzhak who was also a great poet but he tragically left the proper path, apparently converting to Islam.[78] Some took this as a license and went so far as too say that any of the problematic ideas[79] mentioned in the writings of Ibn Ezra were added in by this son.[80] For many years scholars were searching for more details about this sad saga. Finally they found a collection of Yitzchak’s poems which they hoped would shed some light on the matter, but the owner wanted a ridiculous sum of money for it. It was not purchased, and during the Second World War it was lost. Eventually, the collection was found and printed but it turned out that it did not really shed much light on this story.

However, in the same documents that Goitein found about R. Yehuda Halevi, there were many mentions of Yitzchak Ibn Ezra (some in the documents written by R. Yehuda Halevi himself). Both Goitein and Fleischer concluded that although R. Yehuda Halevi was not the father-in-law of Ibn Ezra, his son Yitzchak did marry R. Yehuda Halevi’s only daughter.[81] They go so far as to show that Yitzchak and his wife, R. Yehuda Halevi’s daughter, were supposed to follow him to Eretz Yisroel eventually. So there was indeed a family connection between Ibn Ezra and R. Yehuda Halevi. There is even a letter with instructions from R. Yehuda Halevi for a Yehuda ibn Ezra which some want to suggest was his grandson, son of Yitzchak![82] In Sefardi communities it is not unique at all to name after a living relative.

In conclusion I have shown based on documents from the Cario Genizah that it is likely that the legend recorded by Shalsheles Hakabbalah regarding R. Yehuda Halevi is true and he did indeed make it to Eretz Yisroel and that he died an unusual death. We also see from these documents that the legend which is brought by many that there was a family connection between R. Yehuda Halevi and Ibn Ezra is also true, as Yitzchak, Ibn Ezra’s wayward son married R. Yehuda Halevi daughter.

I would just like to conclude with a great quote from the Chazon Ish which I think is very appropriate here:

דברי הימים וקורות עולם הם מאלפים הרבה את החכם בדרכו, ועל תולדות העבר ייסד אדני חכמתו. ואמנם בהיות האדם אוהב לחדש ולהרצות לפני הקהל, נצברו הרבה שקרים בספרי התולדות, כי בן אדם אינו שונא את הכזב בטבעו, ורבים האוהבים אותו ומשתעשעים בו שעשועי ידידות, ועל החכם להבר בספורי הסופרים לקבל את האמת ולזרות את הכזבים, וכאן יש כר נרחב אל הדמיון, כי טבע הדמיון למהר ולהתקדם ולהגיד משפט, טרם שהשכל הכין מאזני משפט לשקול בפלס דבר על אפנו, והדמיון חוץ משפטו כרגע, מהו מן האמת ומהו מן הכזב (אמונה ובטחון, פרק א אות ח).

[1] For his basic history see Y. Baer,

A History of the Jews in Christian Spain, 1, pp. 66-77;

Encyclopedia Judaicia, 11, pp. 492-501;

Yehudah Halevi, A. Doron, Ed. 1988 and the sources in note 4. See also

S. Werses in

B-Orach Maadah, (Aron Mirsky Jubilee volume), pp. 247-86.

[2] See for example what R. Menahem di Lonzano writes:כי היה מנהג ישראל… לשורר לש”י בליל שבת… וחשובי קדמוני המשוררים… ורבי יהודה הלוי… (דרך חיים, דף כג ע”א).

[3] Its influence is the subject of the beautiful book, A. Shear,

Kuzari and the Shaping of Jewish Identity, 1167-1900, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008 (based on his Phd,

The Later History of a Medieval Hebrew Book, Studies in the Reception of Judah Halevi’s Sefer Ha Kuzari, University of Pennsylvania, 2003)

.

[4] For some more information on R’ Yehuda Halevi in relation to this topic: See; D. Kaufmann,

Mechkarim Besafrus Haivrit Byemei Habenyim pp. 166-207; C. Schirmann,

Toldos Hashirah Haivrit Besefard Hamuslamit, pp. 441-443; M. Ish Sholom,

Kivrei Avos, 1948, pp. 190-192;

Kovetz R. Yehudah Halevi, 1950, pp. 47-65; Y. Burlu, R’ Yehuda Halevi, 1968; Zev Vilnay,

Matzevos Kodesh Beretz Yisroel 2:298-299; E. Reiner revisited this in,

Pilgrims and Pilgrimage to Eretz Yisrael (1099-1517),(PhD dissertation, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1988), pp. 30-33; T. Ilan,

Kivrei Tzadikim, 1997, p. 255; A. Shear,

The Later History of a Medieval Hebrew Book, Studies in the Reception of Judah Halevi’s Sefer Ha Kuzari, (PhD dissertation, University of Pennsylvania), 2003, pp. 95, 513-514; Y. Yahalom,

Judah Haevi: A life of Poetry, Jerusalem 2008, pp. 7-8; R. Scheindlin,

The Song of the Distant Dove: Judah Halevi’s Pilgrimage (Oxford University Press, 2008), pp.150-152, 249-252; Hillel Halkin,

Yehuda Halevi (New York: Nextbook/Schocken, 2009), pp. 236-242. See also Lawrence J. Kaplan,

The Starling’s Caw’: Judah Halevi as Philosopher, Poet, and Pilgrim, Jewish Quarterly Review 101:1 (Winter 2011): 97-132; David J. Malkiel – Three perspectives on Judah Halevi’s voyage to Palestine,

Mediterranean Historical Review, Vol. 25, No. 1, June 2010, 1–15. (Thanks to Menachem Butler for the last two sources).

[5] For more sources on R. Yehuda Halevi and his love of Eretz Yisrael, see: D. Kaufmann, (

supranote 4), pp. 193-194; A. Shear,

supra, pp. 516-517; C. Schirmann,

Letoldos Hashirah Vehadramah Haivrit, vol. one, pp. 319-341; C. Schirmann,

Toldos Hashirah Haivrit Besefard Hamuslamit, pp. 466-480. Franz Kobler,

A Treasury of Jewish Letters, vol. one, p. 155; Abraham Haberman,

Toldos Hashirah Vhapiyut, vol. one, p. 185; R’ Yosef Dov Soleveitchik,

Lord is Righteous in All His Ways: Reflections on the Tish’ah Be-Av Kinot,pp. 304-312.

[6] R’ Yosef Dov Soleveitchik,

Lord is Righteous in All His Ways: Reflections on the Tish’ah Be-Av Kinot,p. 304.

[7] On this

Piyut and how famous it became see A. Doron in

B-Orach Maadah, (Aron Mirsky Jubilee volume), 1986, pp. 233-238[=

Yehudah Halevi, A. Doron, Ed. 1988, pp. 248-254]; B. Bar Tikvah,

Sugot Vesugyot Be-fiyut Hapravencali VeHakatloni, pp. 395-425; I. Davidson,

Otzar Ha-shira Ve-hapiyut, 3, pp. 321-322.

[8] Below I demonstrate that this date is incorrect and that the correct death date is 1141.

[9] The Complete tisha B’av Service, 1998, p. 328. See also R. Yakov Weingarten,

Kinos Ha-Mifurush, 1988, p. 43, 276; Rabbi Berel Wein,

Patterns in Jewish History, 2011, pp. 75-76 (as an aside its worth mentioning that this book is excellent).

[10] The Lord is Righteous in All His Ways: Reflections on the Tish’ah Be-Av Kinot, p. 303. [I would like to thank my friend Rabbi Dov Loketch for bringing this source to my attention]. In the new edition of the Rav’s Kinos this is recorded slightly differently.

[11] See the Gemarah at the end of

Kesuvot.

[12] Sefer Chardeim, p. 208. See also his

Mili Deshmayhu, pp. 4-5. The truth is the author of

Shir Yidddus was not R. Yehuda Halevi, see R. Menachem Krengel in his notes to

Shem Hagedolim, p. 35a; I. Davidson,

Otzar Ha-shira Ve-hapiyut, 1, p. 348.

[13] p. 217, Filipowski ed.

[15] Shalsheles Hakabbalah, p. 92.

[16] Shalsheles Hakabbalah, p. 92.

[17] Koreh Hadoros, p.33. He writes that he heard it from ‘old people’ and then saw it in the

Shalsheles Hakabbalah.

[18] Seder Hadoros, p. 201

[19] Tevous Haaretz, p.443. Benjamin the Second, in his book,

Asia & Africa from 1846-1855, also brings down this story (p.13) but it only appears in the English edition of his work not in the Hebrew.

[20] A. Shear,

Kuzari and the Shaping of Jewish Identity, 1167-1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, pp.162-163.

[21] Besulas Bas Yehuda, pp. 25-29.

[23] Knesset Yisroel,1, p. 400.

[24] Die religiöse Poesie der Juden in Spanien, Berlin: Veit, 1845, pp. 287-291.

[22] Interestingly enough, David Kaufmann uses other evidence to prove that the poems of R. Yehuda Halevi indicate that Jerusalem was under Christian rule (

Mechkarim Besafrus Haivrit Byemei Habenyim p. 194). See also

Sefer Yerushalyim 1099-1250; M. Ish Shalom,

Betzalon Shel Malchus, p. 234. A.M. Luncz in his edition of

Tevous Haaretz, p. 443 also did not believe the story.

[25] See my article in

Yeshurun 24 (2011), pp. 467-468.

[26] Mivchar Kitavim, pp. 215-216. See also Chida,

Shem Hagedolim, Vol. 1, p. 2, Vol. 2, p. 24; A. David, Mifal

Histographi shel Gedaliah Ibn Yachi, Baal Shalsheles Hakabbalah,(PhD dissertation, Hebrew University Jerusalem, 1976) and E. Yassif in

Sippur Ham Haevrei pp. 351-371.

[27] Kovetz R. Yehudah Halevi, 1950, p. 29. See also A. Aderet,

Itineraries in Yiddish to Eretz Yisroel in the 17th and 18th century, (Heb.), Phd Bar Ilan 2006, p. 236.

[28] Machberes Hauruch p. 5.

[29] Independently, we know that during R. Yehuda Halevi’s stay in Egypt he was a prolifi composer. Perhaps, what is meant by the above story, is that he was going to limit the focus of future compositions, not that he was abandoning composing entirely.

[30] Toldos Safrus Byisroel, vol. 1, p. 115. On this trip to North Africa see

Yehudah Halevei U’vnei Chugo, p. 192.

[31] Mechkarim Besafrus Haivrit Byemei Habenyim p. 195.

[32] Amudei Avodah, p.70.

[33] Amudei Avodah, p.76.

[35] Mechkarim Besafrus Haivrit Byemei Habenyim p. 195. Shadal writes it was written in Spain.

[36] There are actually various readings of these words in the manuscripts, but Adler accepts this as the correct reading See his edition of

The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela, London 1901, p. 29. R. Scheindlin (note 5), p. 276 disagrees with Adler’s reading.

[37] See

Masos Eretz Yisrael, pp. 51-53 and

Kovet Al Yad 13:267-269.

[38] Avraham Yari,

Masos Eretz Yisrael, p. 110. Also see J. Prawer,

Toldos Hayehudim Bemamleches Hazelvonim, p. 150

[39] Kovet Al Yad 14:292.

[40] Masos Eretz Yisroel, p. 113.

[41] Iggrot Eretz Yisroel, p. 301.

[42] Masos Eretz Yisroel, p. 438. I would venture to say the author confused R. Shlomo Ibn Gabriel with R. Yehuda Halevi. Both being famous composers, they are sometimes confused. Furthermore, we have no source that R. Shlomo Ibn Gabriel ever came to Eretz Yisrael (aside from a very late letter written in 1747 printed in

Egrot Eretz Yisrael, p. 273). (See also David Kaufmann, p. 205 and

Sinai, vol. 28, p. 290). I have written about this elsewhere. See also R. Moshe Riescher,

Sharei Yerushlayim. p. 151, 145.

[43] Sinai vol. 28, p. 284.

[44] There are a great many articles on this topic see: R. Brody in B. Richler,

Hebrew Manuscripts: A Treasured Legacy, Ofek 1990, pp. 112-133; N. Danzig,

A Catalogue of Fragments of Halakha and Midrash from the Cairo Genizah in the Elkan Nathan Adler Collection of the Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary of America (New York, 1997), 3-39 (Hebrew); A. Hoffman and P. Cole,

Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found World of the Cairo Geniza (New York: NextBook/Schocken, 2011). See also E. Hurvitz,

Catalouge of the Cairo Geniza Fragments in the Westminster College Library, Cambridge, N.Y. 2006

[45] See for example

Yehsurun, 23 (2010), pp. 13-34; S. D. Goitein Moses Maimonides, Man of Action – A Revision of the Master’s Biography in Light of the Geniza Documents,

Hommage à Georges Vajda: études d’histoire et de pensée juives. Louvain: Peeters 1980, pp. 155-167.

[46] R. Brody,

The Geonim of Babylonia and the Shaping of Medieval Jewish Culture (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998)

[47] Shadal first printed a collection of his poems in 1840 but, continued working on it for the many years. Right after he died, in 1864 the

Mekizei Nirdamim Publishing House printed as its first work a more complete edition of R. Yehuda Halevi’s poems from Shadal.

[49] D. Kaufmann, (note 5), p. 175; C. Schirmann,

Toldos Hashirah Haivrit Besefard Hamuslamit, p. 437;

Yehudah Halevei U’vnei Chugo, p. 177.

[50] D. Kaufmann, (note 5), p. 169.

[51] D. Kaufmann, (note 5), p. 170; C. Schirmann,

Toldos Hashirah Haivrit Besefard Hamuslamit, p. 435;

Yehudah Halevei U’vnei Chugo, p. 59, 122; Y.Ta- Shema,

Rebbe Zerachia Halevi, 1992, p. 37.

[52] A Mediterranean Society, p. 462.

[53] There is a lot related to R. Yehuda Halevi in these documents unrelated to this article. Such as an autograph letter where he discusses why he wrote his classic work Kuzari. See

Yehudah Halevei U’vnei Chugo, pp.182-184;

A Mediterranean Society, p. 456, 465; Mordechai A. Friedman,

Judah Ha-Levi on Writing the Kuzari: Responding to a Heretic, in B. Outhwaite and S. Bhayro, eds., ‘

From a Sacred Source’: Genizah Studies in Honour of Professor Stefan C. Reif (Leiden 2011), 157-169. (Thanks to Menachem Butler for this last source). Some of the other autograph letters show him dealing with Pidyon Shivuyim. See

A Mediterranean Society, p. 462-465;

Yehudah Halevei U’vnei Chug, p.178-181. See also Mordechai A. Friedman, “On Judahha-Levi and the Martyrdom of a Head of the Jews: A Letter by Halfon ha-Levi ben Nethanel,” in Y. Tzvi Langermann and Josef Stern, eds.,

Adaptations and Innovations: Studies on theInteraction between Jewish and Islamic Thought and Literature from the Early Middle Ages to the Late Twentieth Century, Dedicated to Professor Joel L. Kraemer (Leuven: Peeters, 2007), 83-108.

[54] Yehudah Halevei U’vnei Chugo, pp. 202-203. See also R. Yehuda Al-charizi,

Sefer Tachomoni, 1952, pp. 46-48

[55] Yehudah Halevei U’vnei Chugo, p. 330. The translation is from S. Goitein,

A Mediterranean Society, volume V, p. 289.

[56] See also C. Schirmann,

Toldos Hashirah Haivrit Besefard Hamuslamit, pp. 421-480.

[57] This is the trip mentioned above from R. Shlomo Parchon. It is pretty clear that he was good friends with Ibn Ezra even before this.

[58] Yehudah Halevei U’vnei Chugo, p. 483. On the significance of his departure being on Shavuos see Y. Ta-Shema,

Halacha, Minhag U-mitzios Be-Ashkenaz 1100-1350, 2000, p. 179; J. Katz,

The Shabbes Goy, 1989, pp. 35-48.

[59] Yehudah Halevei U’vnei Chugo, pp. 253-254, 494, 495.

[60] The Jews in Egypt and in Palestine under the Fatmid Caliphs, 1, 1920, pp. 224-225.

[61] Yehudah Halevei U’vnei Chugo, pp. 254-256, 484-490. See also Goitein in

Tarbitz, 46:245-250.

[62] Yehudah Halevei U’vnei Chugo, p. 256, 496.The truth is this proof alone is not enough as a friend pointed out to me in Genizah documents we do find זקל and זל for example if one looks in the Shut of R. Avraham ben HaRambam printed by Goitein, in 1937 which is based on documents from the Cario genizah one will see זל, זצל andזקל for זל andזצל see p. 1,4, 7,10,13,26 & many more place. Forזקל see p. 9,104, 161,170. A search on the Princeton Genizah Project shows thatזל and זצל are much more common than זקל but זקל does appear over 36 times.

[63] For other possible explanations why R. Yehuda Halevi wanted to go to Eretz Yisroel see. S. Abramson,

Kiryat Sefer, 29 (1953), pp.133-144; David J. Malkiel – Three perspectives on Judah Halevi’s voyage to Palestine,

Mediterranean Historical Review, Vol. 25, No. 1, June 2010, 1–15. Also see J. Prawer,

Toldos Hayehudim Bemamleches Hazelvonim, pp. 154-156.

[65] Pe’amim 68, pp. 4-15.

[66] A Mediterranean Society, volume V, pp. 449-450. On the political situation in the times of the Kuzari, see Y. Baer,

Mechkarim, pp. 251-268.

[67] Peletas Beis Yehudah, 1971, pp. 84-88. (I would like to thank my friend Rabbi Eli Meir Cohen for bringing this source to my attention.)

[68] Yehudah Halevei U’vnei Chugo, p. 205.

[69] Le-Or Ha-Halachah, 2004, pp. 358- 377.

[70] Chazon Ish,

Kuntres Yud Ches Shoess, p. 186. See also

Genazim Ve-shut Chazon Ish, pp. 205-290 just printed this week [make sure to get it while it is still around] See also

here for an interesting work on the topic. See B. Brown,

Ha-Chazon Ish, 2011, pp. 612-637. See also R Alexander Moshe Lapides,

Toras Hagoan Rebbe Alexander Moshe, p. 20, 23; see also R Chaim Zimmerman,

Agan Ha-sahar, p. 427. R. Aryeh Rabinowitz,

Toras Haolam Ve-Hayehadus, part 4, 29a. [As an aside, on this author see what the Chazon Ish writes:

וראיתי להגאון האדיר ר’ אריה ממינסק בספרו באר היטב… (חזון איש, קדשים ס’ כו אות טז).

The Chazon Ish does not use such language frequently. [Thanks to my Uncle, Rabbi Sholom Spitz for pointing out this source to me].

The truth is this whole issue is not so simple as the Ravad comments on the Baal Ha-Maor:

והריח אשר הריח מן הכוזרי ומחבורי רבי אברהם ב”ר חייא הספרדי כי הם פירשו ההלכות הללו על זה הדרך עצמו והוא מתעטר בעדים שאינם שלו, אין לנו ללמד מדברי מי שאינו מאנשי התלמוד לפי שהם מסבבים פני ההלכה לדבריהם כאשר לא כן. וכבר שמענו כי הנשיא רבי יצחק ב”ר ברוך ז”ל שהיה בקי בזו החכמה והיה בקי בהלכה שבר את הדברים האלה ויישר כחו ששבר… ועם כל זה ואריכות דבריו אין הלכה יוצאה לאור מדבריו, רק ממה שכתב בספר הכוזרי…יוצא לאור לפי הסברא ההיא(כתוב שם, לראב”ד, ראש השנה ה ע”א).

He is complaining that he plagiarized from the Kuzari but we do not pasken like him anyways…and was not a talmudist! The truth is it is possible that the Chazon Ish gave much more weight to Kuzari as he held there is no such thing as being a

Baal Aggdah alone. I am referring to the censored passage from the

Chazon Ish Emunah U-bitchon where he writes:

אלה שלא זכו לאור הגמ’ בהלכה, המה משוללים גם מאגדה באפיה האמיתי. כי בהיותו חסר לב חכמה, אי אפשר לו לקנות מושגים שמימיים אמיתיים, גם אינו מסוגל ללימודים מישרים. ומה שהזכירו בגמ’ בעלי אגדה – היינו חכמים בהלכה שהוסיפו עיונם גם באגדה, אבל לא יתכן להיות ריק מהלכה ולהיות בעל אגדה. ויתכן אנשים שעסקם בהגיונות בני אדם כעין פילוסופי’ ריקנית, פעם במדות פעם בקורות הדורות ועוד כיוצא בהם, ומשתדלים לקבוע הגות לבם במסגרת התורה, ויתכן שיצליחו למשוך לב השומעים ולהנעים זמירות באזני המקשיבים. ואמנם אלה אין להם חלק בתורה, לא בהלכה ולא באגדה, כי כיסוד ההלכה יסוד האגדה. אין אגדה הגיון לב – האגדה היא חלק התורה שקבלנוה דור אחר דור, אשר מסרה משה ליהושע ויהושע לזקנים וכדתנן באבות. ולהיות בעל אגדה החובה להיות בקי במקרא בתורה בנביאים וכתובים, להיות בקי בכל אגדות שנאמרו בגמ’ בקיאות נאמנה, להיות בקי במדרש בקיאות שנונה ומסודרת, ואחר כך לשאת ולתת בהן בהבנת המסקנות שבהם, וכמו שלא יתכן חכם בהלכה בלא קנין הבקיאות המרובה.

So the Kuzari had to be a star Talmudist too. On this issue see Y.Ta- Shema,

Rebbe Zerachia Halevi,1992, p. 4; I. Twersky,

Rabbad of Posquieres, p. 266.

On these censored pieces of the Chazon Ish see B. Brown,

Ha-Chazon Ish, 2011, pp. 166-167 (and see

here). It’s worth mentioning these pieces have been finally printed in an authorized version from the family this week in a work called

Genazim Ve-shut Chazon Ish, pp. 106-112.Besides for the Ravad writing against the Kuzari on this topic see also in the sefer

Divrei Chachomim on the dateline, p. 27:

וראיתי כי אין ללמוד להלכה מדברי הכוזרי הנ”ל, כי כמו שאין למדין הלכה מן ספרי המקובלים… כן אין למדין הלכה מן ספרי מחקר ודרוש כהכוזרי…

[72] See Y. Zisberg,

Medieval Rabbinic Attitudes towards the Land of Israel and the Religious Obligation of its Settelment, (PHd Bar Ilan 2007), pp. 48-57 who has an excellent discussion on this topic.

[73] It is not clear if Ibn Ezra ever even made it to Eretz Yisroel see N. Ben Menachem,

Inyani Ibn Ezra, pp. 182-190, 239; Uriel Simon, Transplanting the Wisdom of Spain to Christian Lands: The Failed Efforts of R. Abraham Ibn Ezra, S

imon Dubnow Institute Yearbook 8 (2009) 139-189; Zisberg, supra, pp. 58-68. Regarding where he is buried see: M. Ish Sholom,

Kivrei Avos, 1948, p.189; Zev Vilnay,

Matzevos Kodesh Beretz Yisroel 2:299; T. Ilan,

Kivrei Tzadikim, 1997, p. 255.

[74] supra p. 206. See also Yakov Reifman,

Iyunim BeMishnat Harav Ibn Ezra, 1962, pp. 95-97, 56; N. Ben Menachem,

Inyani Ibn Ezra, pp. 225-233; Y. Ibn Shmuel,

Kuzari, pp. 371-372; E. Fleischer,

Hashira Haivrit Besefard, 2, pp. 266-267. However see A. Shear,

Kuzari and the Shaping of Jewish Identity, 1167-1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 23 and his doctorate,

The Later History of a Medieval Hebrew Book, Studies in the Reception of Judah Halevi’s Sefer Ha Kuzari, (PhD dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 2003, pp. 96-97) who concludes that Ibn Ezra did not see the Kuzari’s work.

[77] N. Ben Menachem,

Inyanei Ibn Ezra, pp. 233-240, 346-356 collected many version of this Legend. See also: R. Dovid Ganz, Tzemach David, p. 121; R. Yosef Sambori,

Divrei Yosef, p. 100;

Shut Chavos Yair, siman 248; R’ Yosef Dov Soleveitchik,

Lord is Righteous in All His Ways: Reflections on the Tish’ah Be-Av Kinot, p. 304-305;

Kovetz R. Yehudah Halevi, 1950, pp. 84-93. See also A. Shear,

Kuzari and the Shaping of Jewish Identity, 1167-1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008. p. 298.

Interestingly enough the Meiri in his

Seder Hakablah and the

Sha’ari Zion make no mention of this relationship between Ibn Ezra and R. Yehuda Halevi.

[78] Sefer Tachkemoni, 1952, p. 45.

[79] A topic worthy of its own article in the Future B”h.

[80] N. Ben Menachem,

Inyani Ibn Ezra, p. 255.

[81] Yehuda Halevei U’vnei Chugo pp. 148-173. Many agree with this suggestion but some still disagree (see ibid, pp. 250-251). See Halkin, (note 5) pp. 330-335. For more on this whole sad affair with the son of Ibn Ezra see E. Fleischer in

Toldos Hashirah Haivrit Besefard Hanotzrit, pp. 71-92; E. Fleischer,

Hashira Haivrit Besefard, 2, pp.264-270. See also Y. Levine, Avrhom Iban Ezra, 1970, p. 17.

[82] Yehuda Halevei U’vnei Chugo pp. 491-494. See also E. Fleischer,

Hashira Haivrit Besefard, 2, pp. 270-273; D. Kaufmann (note two), p. 190, 201.

Interestingly enough the Meiri in his Seder Hakabbalah and the Sha’ari Zion make no mention of this relationship between Ibn Ezra and R. Yehuda Halevi.