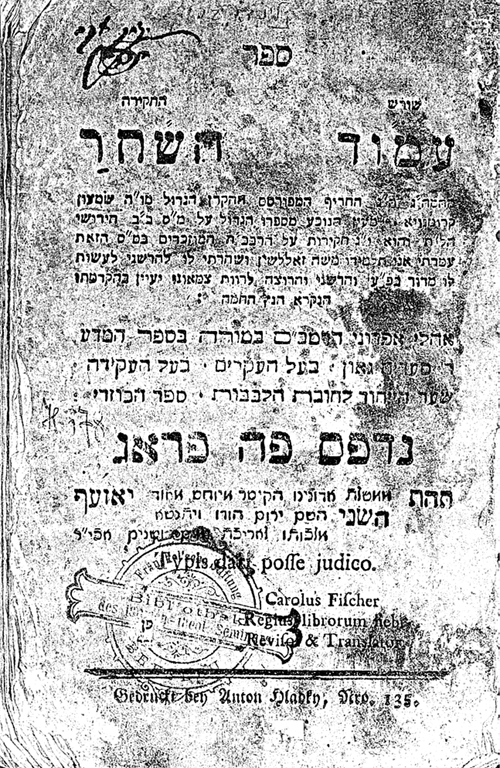

An (almost) Unknown Halakhic Work by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi and an attempt to answer the question: who punctuated the first edition of the Shulhan Arukh?

An (almost) Unknown Halakhic Work by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of

Liadi and an attempt to answer the question: who punctuated the first edition

of the Shulhan Arukh?

by Chaim Katz

Chaim Katz is a

database computer programmer in Montreal Quebec. He graduated from McGill

University and studied in Lubavitch Yeshivoth in Israel and New York.

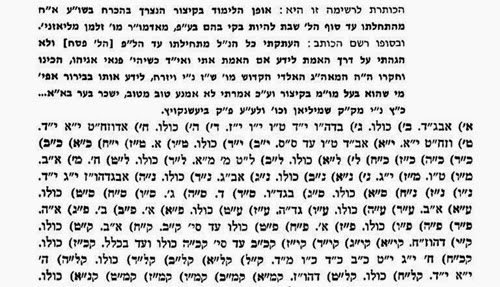

published a manuscript, which was a list of chapters and paragraphs (halakhot and se’fim), selected by Rabbi Shneur

Zalman of Liadi (RSZ), from the Shulhan Arukh (SA) of Rabbi Yosef Karo.[1]

(RYK)

Shneur Zalman and the preliminary and concluding notes written by R. Isakhar

Ber.

Isakhar Ber, who copied the original manuscript, explained the purpose of the

list in a preliminary remark:

of essential laws from the beginning of Shulhan Arukh Orah Hayim until the end of the Shabbat laws – to know them

fluently by heart, from Admur (our master, teacher and Rebbe), our teacher

Zalman of Liozna.

Isakhar also added an epilogue:

above, from the beginning until the laws of Pesah, but I didn’t check it

completely to verify that I copied everything correctly and G-d willing when

there’s time I will check it. Prepared and researched by the Rabbi and Gaon,

the great light, the G-dly and holy, our teacher, Shneur Zalman, may his lamp

be bright and shine, to know it clearly and concisely, even for those people who

are occupied in business. Therefore I thought I won’t withhold good from the

good. Isakhar Ber, son of my father and

master … Katz, may his lamp be bright, of the holy community of Shumilina and

currently in Beshankovichy.

manuscript was probably composed (or at least copied), between the years

1790-1801, when RSZ lived in Liozna. The existence of this list isn’t

acknowledged in any source that Rabbi Mondshine was aware of, and obviously the

list was never published in book form, either because RSZ

decided not to publicize it or because the list was simply put aside and

forgotten.

wasn’t the first who envisioned a popular digest of the SA. Rabbi Yehuda Leib

Maimon lists four works that preceded the famous Kitzur Shulhan Arukh.[2]

They preceded RSZ’s work as well and are all quite similar although they also

have their differences.

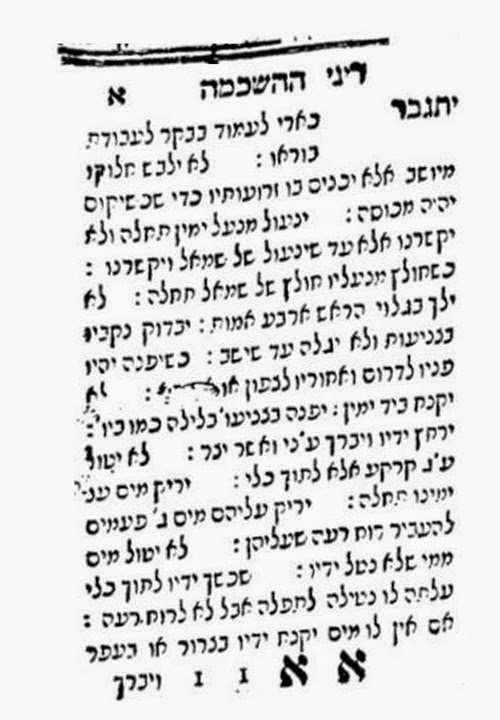

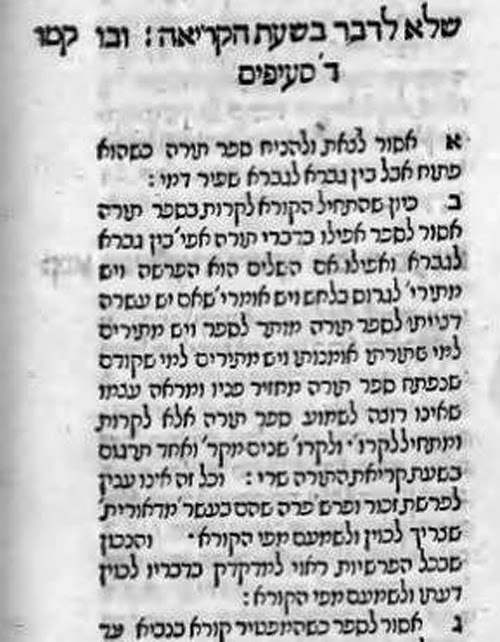

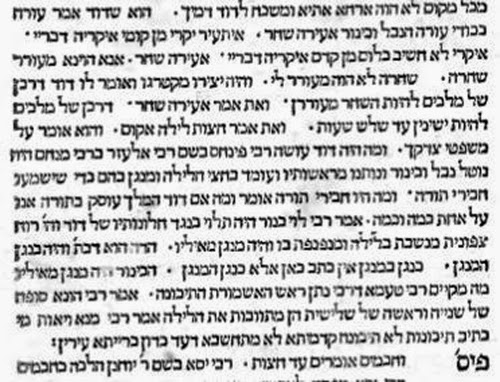

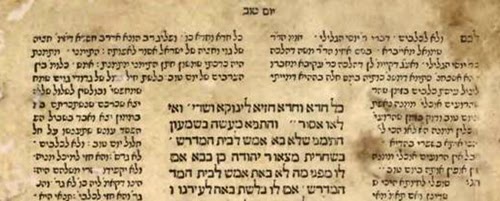

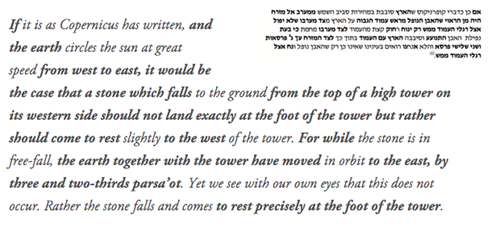

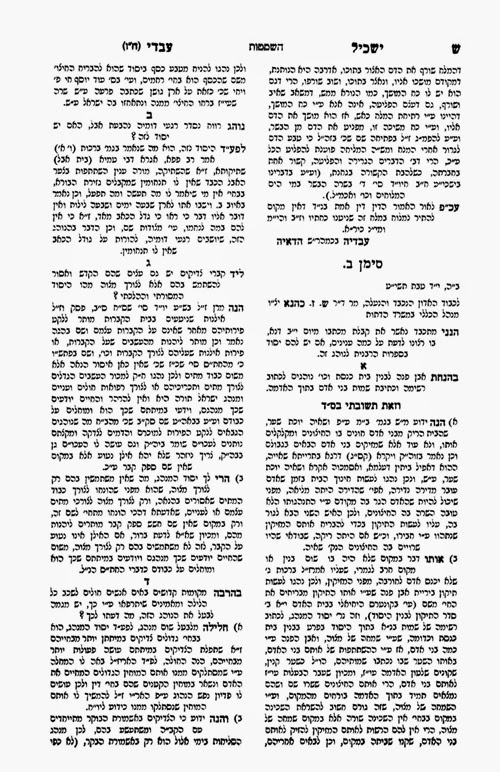

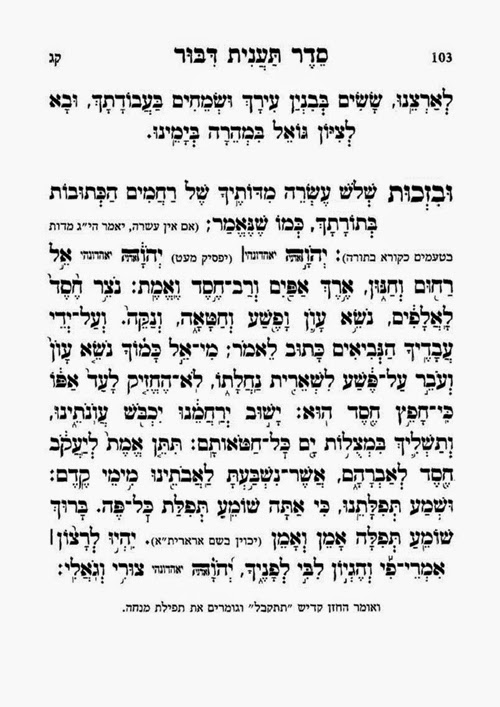

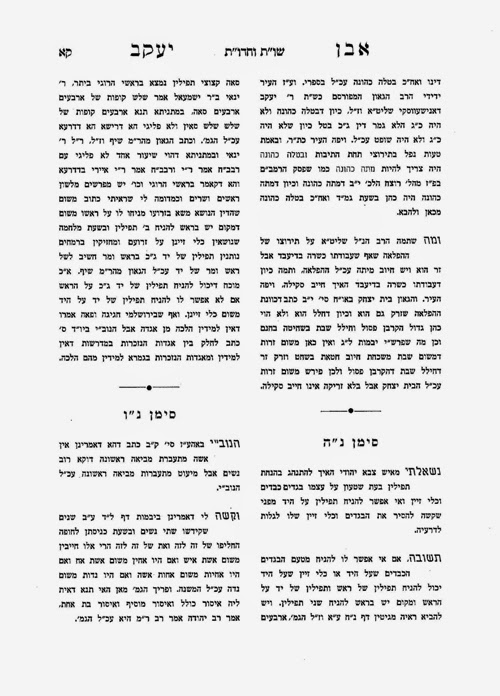

Figure 2: First edition of Shulhan Tahor by Rabbi Joseph Pardo (from

Hebrewbooks.org). The page summarizes three and a half chapters of the original

Shulhan arukh. Note how the author sometimes combines the words of RYK with the

words of Rema (line 11).

Others have a narrower scope and cover only Orah Hayim. RSZ covers even less.

Some collections are abbreviated extensively; others include more details.[3]

There are variations in the language and content; some quote opinions of later

authorities, some quote Kabbalah, some re-cast the language of the SA and some

retain the language as much as possible.

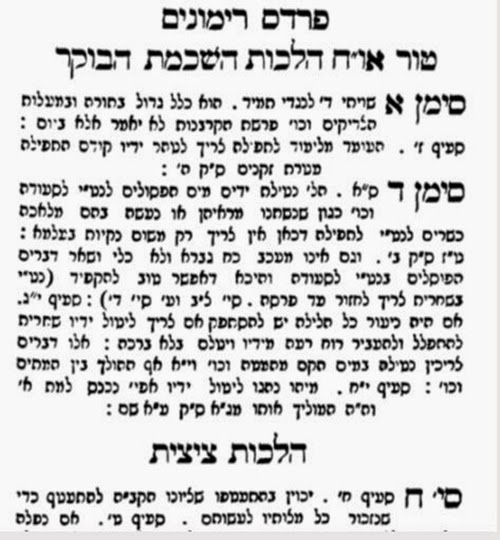

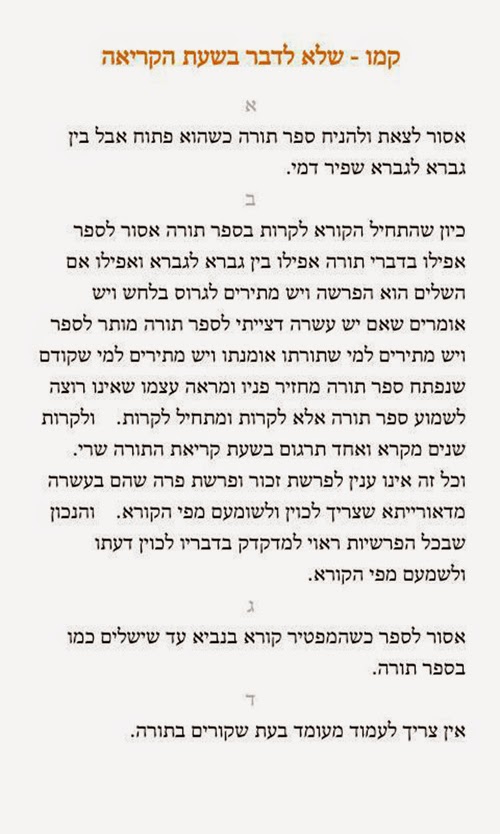

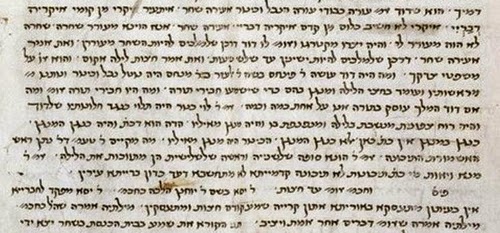

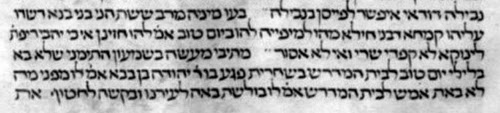

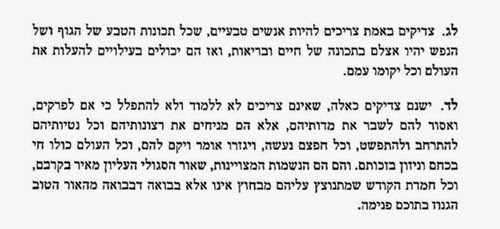

Hebrewbooks.org), composed in 1784. Note the author quotes Ateret Zekenim, (R.

MM Auerbach, published in 1702). The additions in parenthesis are by the

publisher of the 1879 edition.

two goals in mind. One of the goals was to make the basic rules and practices

of the SA more accessible. To this end, certain subjects or details were left

out because they were too technical for the chosen audience. Other rules were

omitted because the situations to which they applied happened only infrequently

(בדיעבד). Many regulations

were left out because daily life and its circumstances had changed so much

since the sixteenth century.

The other goal,

and arguably the primary goal, was to provide a text of law that could be

memorized. In the introduction to Shulhan Tahor, the author’s son writes:

“every man will be familiar and fluent in these laws (שגורים בפי כל האדם)”. Likewise, the

author of Pardes Rimonim defines the purpose of his work: “so that the reader

will be fluent in these rules (שגורים

בפיו)

and will review them each month”. In

the introduction to the Shulhan Shlomo, the author writes: “Put these words to

your heart and you won’t forget them”, and the motive of R. Shneur Zalman’s

work is: “to know [these laws] fluently by heart”.

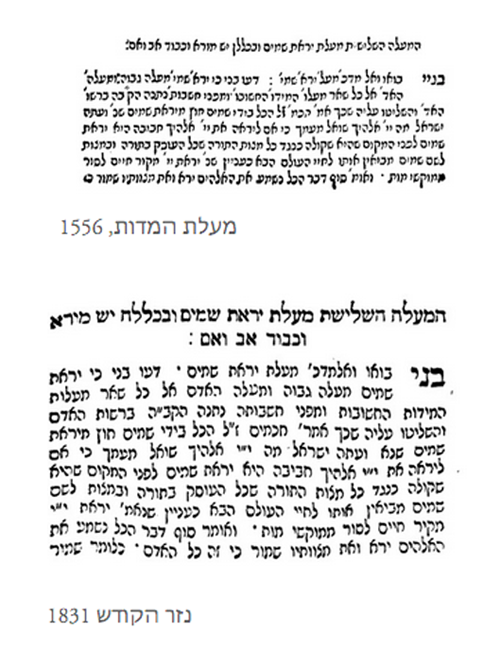

of the Shulhan Arukh, published in Venice in 1565 where memorization is

emphasized (from the scanned books at the website of the National Library of

Israel, (formerly the Jewish National and University Library.)

tradition of memorizing practical laws goes back to RYK himself, and probably

goes back even earlier.[4]

RYK writes in the introduction to his Shulhan Arukh:

that it is fitting to gather the flowers of the gems of the discussions [of the

Beit Yosef] in a shorter way, in a clear comprehensive pretty and pleasant

style, so that the perfect Torah of G-d will be recited fluently by each man of

Israel. When a scholar is queried about a law, he won’t answer vaguely.

Instead, he will answer: “say to wisdom

you are my sister”. As he knows his sister is forbidden to him, so he knows the

practical resolution of every legal question that he is asked because he is

fluent in this book… Moreover, the

young (rabbinical?) students will occupy themselves with it constantly and

recite its text by heart…

working on a phone version of RSZ’s work using the first print of

RYK’s SA for that portion of the text. However, (aside from the difficulty of

text justification in an EPUB), there is one typesetting decision that I’m

wondering about. The first edition of

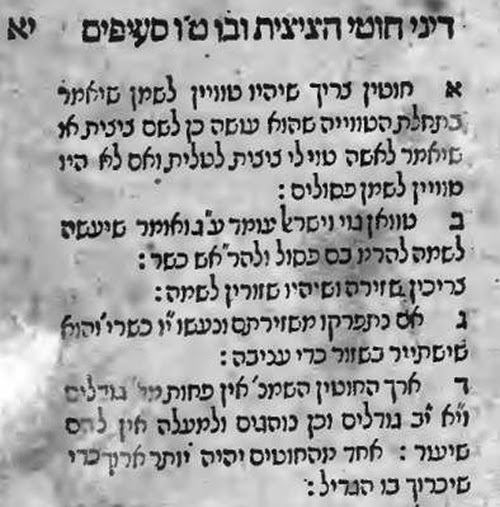

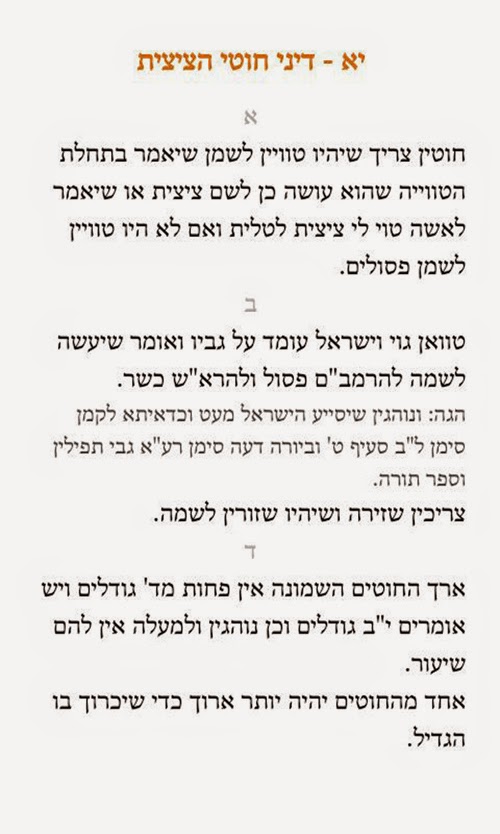

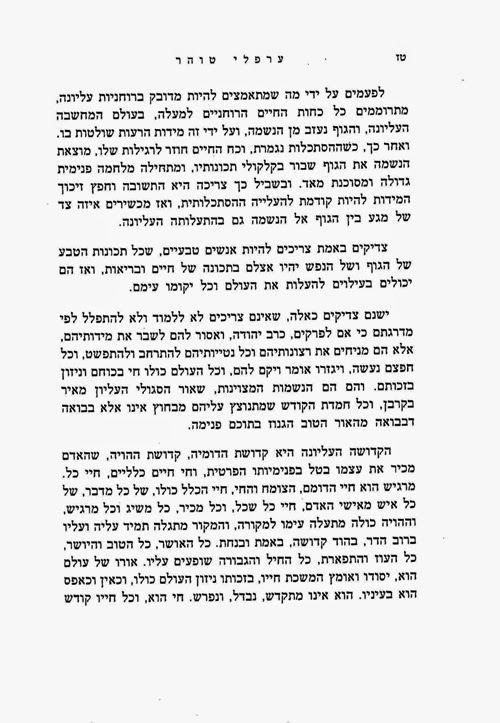

the SA is punctuated with elevated periods and colons. The colons always separate each halakha, but

infrequently colons appear in the middle of a halakha. Sometimes followed by a

new line and sometimes not. The periods may appear in the middle of a halakha,

sometimes followed by horizontal white space and sometimes not.

much in the past 450 years; the colons at the end of each paragraph are present

in most current editions of the Shulan Arukh, but the periods, colons and white

space in the middle of the paragraphs have largely been ignored in subsequent

prints.[5]

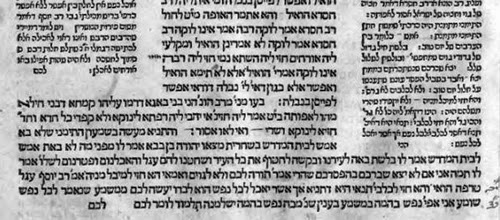

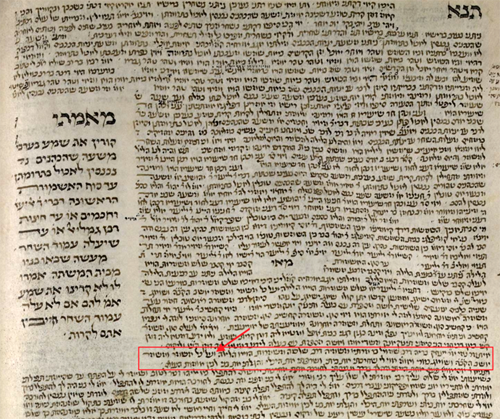

Do I try and duplicate this punctuation or not? Here are two examples where I

replaced the elevated period and colons with modern periods, but tried to keep

the original layout.

(from the National Library of Israel web site).

composition. Note periods and line feeds.

of chapter 11. See the colons in in the fourth halakha.

list – chapter 11

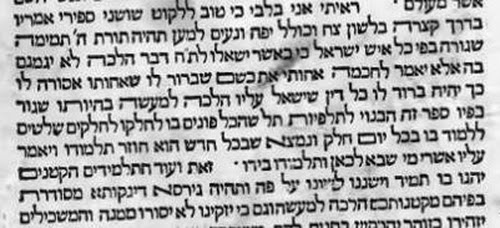

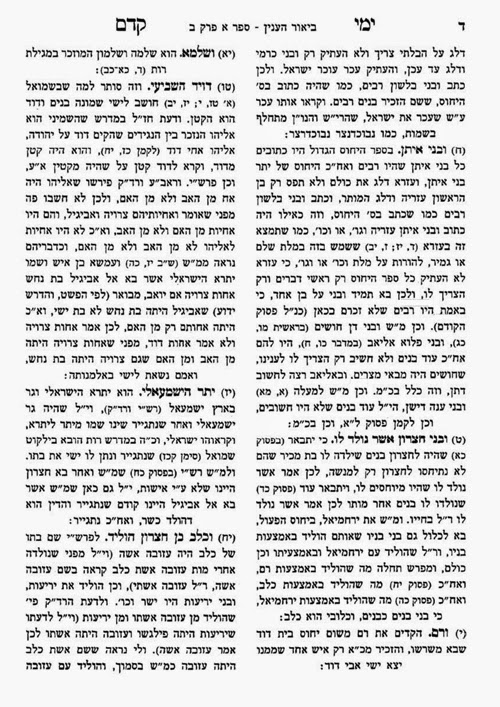

the punctuation of the first edition of the SA was copied from RYK’s manuscript. Prof.

Raz-Krakozkin writes: He (Karo) insisted on personally supervising its

publication and made sure that the editors followed his instructions[6]. On

the other hand, I can’t explain why the punctuation marks occur so rarely.

punctuated his manuscript before sending it to the printers, we can compare

other manuscripts that were printed then. For example, the Yerushalmi was first

printed in Venice (1523) from a manuscript, which is still extant today.

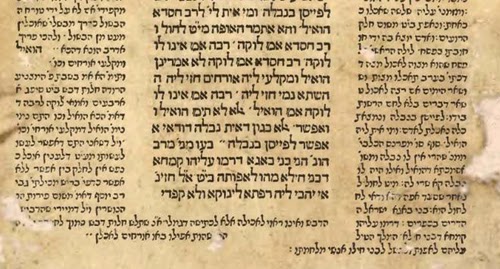

(Berakhot 1:1), with raised periods to separate word groups from the scanned

books at the website of the National Library of Israel, (formerly the Jewish

National and University Library.)

Yerushalmi has elevated periods that delineate groups of words. These markings

are already found in the source manuscript in the exact same places.

(1289 CE), Brakhot 1:1 from the Rabbinic Manuscripts on line at the National

Library of Israel web site, (formerly the Jewish National and University

Library).

speaks of two possibilities concerning the origin of the

Talmud Yerushalmi’s punctuation. The punctuation may be relatively recent – the

scribe punctuated the text or the punctuation existed in the manuscript that

the scribe copied from. Alternatively,

the punctuation might be a reduction or simplification of cantillation marks

that were common in much older rabbinic manuscripts. Either way, the printers

didn’t invent the punctuation.

dots”) in strategic places.[8]

These colons already exist in one of the first Talmud editions – the Bomberg

Talmud (Venice 1523).

colons. (The horizontal lines near the colons are either blemishes, or markings

by hand.) Note the horizontal white space after the colons.

edition were not printed from manuscript, but were copied from the Talmud

printed by Joshua Moses Soncino in 1484[9].

In the Soncino Talmud, we find separators in the exact places as the colons of

the Bomberg edition. The Soncino Talmud had two types of

punctuation: a top comma (or single quote mark) that marks off groups of words

(like the Yerushalmi has) and a double top comma (double quote mark). When

Bomberg printed his edition (40 years later), his printers replaced the double

commas with colons (and dropped the single commas).

page (21a) in Betza. Note the two elevated commas, where we have a colon and

the subsequent horizontal white space. (The Soncino Talmud does not have the

same pagination as us). From the National Library of Israel web site.

to our Betza 21a. Note again 2 commas where we have a colon.

We don’t know which manuscripts were used by the printers of the Babylonian

Talmud, and in any case the many Talmud burnings in the 1550’s in Italy

destroyed most of the manuscripts that were there. Nevertheless, there is at

least one old manuscript that has punctuation marks similar to what we find in

the Soncino Talmud.

manuscript showing the upper double comma separator for the same page – Betza

21a (From the Rabbinic Manuscripts on line at the National Library of Israel

web site, (formerly the Jewish National and University Library).)

The Gottingen manuscript is a Spanish

manuscript from the early thirteenth century[10] – almost three hundred years older than the Talmud printed

in Soncino. It doesn’t have the upper single commas that Soncino edition has,

but it does have the same double comma in the same places that the Soncino

print has. Just to repeat: the pauses

represented by colons, that we see in our Talmud are at least 800 years old!

punctuated just as the Talmudic manuscripts that he studied from were.

Summary

abbreviated (Kitzur) SA, and discussed it in the context of other similar

works. I mentioned that the authors aimed at producing collections of relevant laws

that could be memorized. I noted that the first edition of the SA was punctuated

differently from following versions. I suggested (based on comparisons with

early printed Talmuds) that the punctuation was probably the work of RYK and

not the work of the printers.

(1984). Migdal Oz (Hebrew), Kfar Habad: Machon Lubavitch , pp. 419-421. Dedicated to the memory of Rabbi

Azriel Zelig Slonim ob”m. Essays on Torah and Hassidut by our holy Rabbis, the

leaders of Habad and their students, collected from manuscripts and authentic

sources and assembled with the help of the Almighty.

Leib, The history of the Kitzur Shulhan Arukh (Hebrew), published in Rabbi Shlomo

Ganzfried, Kitzur Shulhan Arukh, Mossad Harav Kook Jerusalem Israel 1949. The

earlier works mentioned are: Shulan Tahor by R. Joseph Pardo,edited/financed by

his son David Pardo, Amsterdam 1686. Shulan Arukh of R. Eliezer Hakatan by Eliezer Laizer Revitz printed by his

son-in-law R. Menahem Azaria Katz, Furth

1697. Shulhan Shlomo by Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Mirkes printed in Frankfort

(Oder) 1771. Pardes Rimonim by R. Yehuda Yidel Berlin, composed in 1784 and

printed for the first time in Lemberg (Leviv) 1879.

beginning until the end of chapter 156 contains 18,000 words while the same

portion of the big Shulhan Arukh contains approximately 40,000 words. A word is

loosely defined as a group of characters separated by a space or by spaces.

the Mishne Torah, Maimonides writes: “I divided this composition into legal

areas by subject, and divided the legal areas into chapters, and divided each

chapter into smaller legal paragraphs so that all of it can be memorized.” See: Studies in the Mishne Torah, Book of

Knowledge Mossad Harav Kook, Jerusalem (Heb.) by Rabbi José Faur for a

discussion and explanation of the study methods of Middle Eastern Jews (page 46

and following pages, especially footnote 60).

Israel, (formerly the Jewish National and University Library) has the edition

of the Shulhan Arukh printed in Krakow in 1580. This is the second version with

the notes of the Rema (which was first printed in 1570) and it doesn’t have the

original punctuation marks.

to Venice: The Shulhan ‘Arukh and the Censor” (in: Chanita Goldblatt, Howard

Kreisel (eds.), Tradition, Heterodoxy and Religious Culture, Ben

Gurion University of the Negev (2007)

91-115).

A.M. Haberman, The First Editions of the Shulhan Arukh

(Heb.) on the daat.ac.il web

site, (from the journal Mahanaim # 97 1965 p 31-34.) suggests that the

editor/corrector of the first edition, Menahem Porto Hacohen

Ashenazi created its table of contents.

See also the discussion about who created the chapter headings, (a

pre-requisite for the table of contents), in Gates in Halakha (Heb.), Rabbi

Moshe Shlita, Jerusalem 1983, page 100. He argues that the chapter headings of

the Shulhan Arukh could not be the work of Rav Yosef Karo.

According to Ms Or 4720 of the Leiden University Library, Academy of the Hebrew

Language Jerusalem 2001 Introduction by Yaakov Sussmann.

beginning of Leviticus “What is the purpose of the horizontal white-space (in

the text of the Torah)? It gives Moshe some space to contemplate between a

section and the next section, between a topic and the next topic. (Rashi Lev. 1:1 s.v. vayikra el Moshe (2nd)

from the Sifra.

Rabbinovicz. Essay on the printing of the Talmud (Hebrew).

Oral Torah, Halakha, Mishna, Tosefta, Talmud, External Tractates (Compendia

Rerum Iudaicarum Ad Novum Testamentum)