Truth be Told[1]

by Aryeh A. Frimer*

Comments on Changing the Immutable: How Orthodox Judaism Rewrites its History by Marc B. Shapiro (Oxford – Portland, OR: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2015).

*Rabbi Prof. Aryeh A. Frimer holds the Ethel and David Resnick Chair of Active Oxygen Chemistry at Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002, Israel; email:

Aryeh.Frimer@biu.ac.il. He has lectured and published widely on various aspects of “Women and

Halakha;” see

here. His most recent paper is: “Women,

Kri’at haTorah and

Aliyyot (with an Addendum on Partnership

Minyanim),” Aryeh A. Frimer and Dov I. Frimer,

Tradition, 46:4 (Winter, 2013), 67-238, available online

here.

I found R. Prof. Marc Shapiro’s new book Changing the Immutable a fascinating read and very hard to put down. The first seven chapters deal with censorship of halakhic and philosophical works, while the eighth focuses on lying and misrepresentation in pesak. As we know from his previous works, Shapiro has a very fluid writing style and the subject matter is always well researched. He does his best to be honest, unbiased and complete in his presentation. He is, moreover, intrigued with exploring the limits of the traditional consensus, which makes for some captivating reading. Yet, despite all these wonderful qualities – or perhaps, because of them, I found the present volume particularly unsettling and disconcerting.

R. Jacob J Schacter’s classic article “Facing the Truths of History” had already sensitized me to the fact that publishers censor and even rewrite portions of the books they bring to press.[2] They do so because they find some of their author’s positions “unacceptable” – views which don’t fit the publishers’ or the intended reader’s “party line.” That such censorship continues unabashedly in the 21st century is disappointing, but then “there is no shame anymore.” But these are, by and large, sins of omission; somehow, with that I could live.

But what I found particularly troubling with Changing the Immutable was the last chapter, which deals with lying in pesak. After going through the many examples Shapiro cites, the reader is left with one clear impression. One sometimes needs to be careful about trusting a Posek, since he may well be misrepresenting something in his ruling. It could be the source and authority of the prohibition. For example, is the prohibition based on a biblical commandment (positive or negative), rabbinic edict, custom or mere public policy (slippery slope) considerations? Alternatively, the expressed reason may not be the real grounds for the prohibition. In addition, the application may be much broader than halakhically permitted. To my mind these are shocking revelations: these are not sins of omission but commission; the perpetrators are scholars and religious leaders; and these deviations constitute intellectual dishonesty at its worst.

Our author is not insensitive to this dissonance. In an attempt to explain how these scholars justify not being fully honest in pesak, Shapiro writes in the last two pages of the book (pp. 284-285) about “redefining truth.” He indicates that these decisors see nothing wrong in what they are doing, since their ultimate goal is the “higher good”. As they see it, they have ultimately prevented their respective communities and congregants from sinning and deviating from the proper path of shemirat mitsvot. The fact that these scholars have bent the truth, and distorted Jewish law in the process, is of lesser importance. The ends in these cases, justify the means.

It is with these jarring observations that the book comes to an abrupt end, without any further comment or soul-searching. This is despite the fact that on page 239ff, Shapiro brings one citation from Hazal after another about the centrality of truth, and the seriousness of the sin of lying. After all, the Torah itself commands us: “mi-Devar sheker tirhak” – “From untruthfulness, distance thyself” (Exodus 23:7). If what the author writes in the last chapter is true, then Hazal’s eloquent statements about the importance of honesty have become nothing but a mockery. It raises serious moral questions with insufficient and unsatisfying answers. How are we now supposed to educate our children and talmidim as to the cardinal nature of truth and truthfulness?! How are we to live with such a clash between theory and practice?

In the course of our own study of Women’s Tefilla Groups, my brother R. Prof. Dov Frimer and I researched misrepresentation in

pesak in the context of women’s issues.

[3] Many leading Rabbis were deeply and justifiably concerned that some of the feminist practices introduced were ultimately “bad for the Jews” on public policy grounds.[4] But instead of saying so clearly, some rabbis adduced reasons that were not halakhically sound. Our own research has led us to the clear conclusion that the vast majority of the

gedolim do not condone this type of misrepresentation or that discussed in the last chapter of

Changing the Immutable. Giving an erroneous ruling – despite one’s good intentions, or even misstating the reason or source for a prohibition, violates the prohibition “

mi-Devar sheker tirhak“, if not a variety of other

issurim.

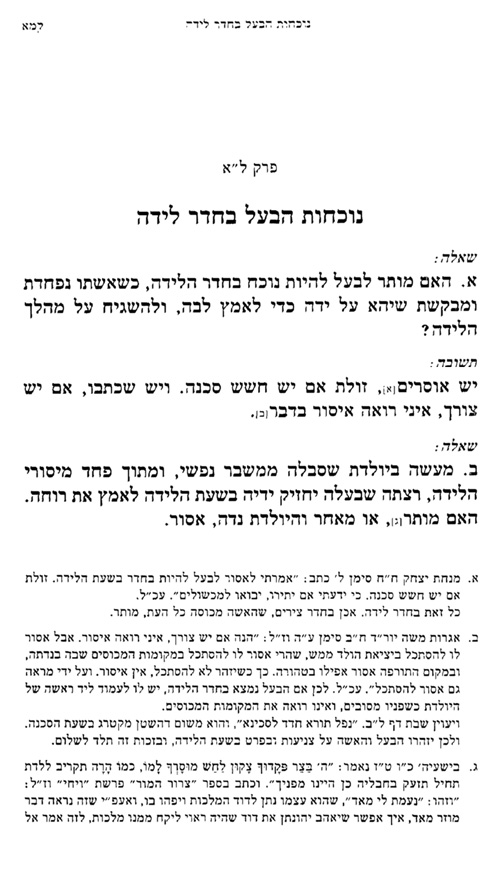

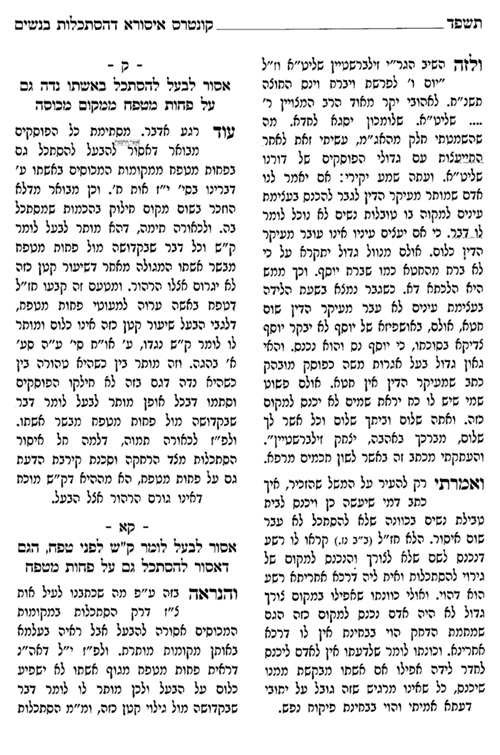

We begin our discussion of this issue with the famous

Pesak Din (halakhic ruling) promulgated by a conference of rabbis who met in Michalowce Hungary in 1865. This edict initially signed by twenty-five leading rabbinic figures and subsequently by many more, ruled that nine practices (including,

inter alia, synagogue choirs, sermons in the vernacular, synagogues weddings, absence of a central

bima, canonical robes for the

Hazan) were halakhically forbidden. Leading rabbis Moses Schick and Esriel Hildesheimer and many of their colleagues refused to sign. The fundamental claim of Rabbis Schick and Hildesheimer was that, contrary to the impression given by the

Pesak Din, the only grounds for some of the edicts were public policy (

mi-gdar milta) – not halakhic – considerations.[5] The term “

Pesak Din” (legal ruling) was in fact a conscious misnomer, an attempt to hide the truth, and, hence, a flagrant deviation from Jewish law with which they could take no part. R. Schick also argued that, since the

Pesak Din was promulgated by a Jewish court, it violated

bal tosif, adding a

mitsva to the Torah.[6]

Similarly, R. Zvi Hirsch Chajes[7] argues that it is forbidden to call a rabbinic edict a biblical prohibition because it violates not only bal tosif but also mi-devar sheker tirhak. Similarly, R. Chayim Hirschensohn[8] charges those rabbis who forbid women to become involved in politics with violating both bal tosif and lying. R. Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk[9], maintains that both Ra’avad and Rambam agree that “mi-devar sheker tirhak” forbids a posek from claiming that a rabbinic injunction is biblical. R. Jacob Israel Kanievsky,[10] refuting the suggestion that it is forbidden to take part in elections in the secular State of Israel, writes: “…And your Honor should know that even to be zealous, it is forbidden to teach Torah not according to the halakha (Avot V:8), and that which is not true will not succeed at all.” R. Haim David Halevi[11] prohibits a posek from misrepresenting halakha and/or giving an erroneous reason for a prohibition for two basic reasons: (1) the biblical prohibition of “mi-devar sheker tirhak” and (2) a total loss of trust in rabbinic authority would result should the truth become known (see more below). [See also the related opinions of Rabbis Ehrenberg, Rogeler and Sobel cited below.]

As Prof. Shapiro documents in

Changing the Immutable, some

posekim dissent. They argued, on various grounds, that “

mi-devar sheker tirhak” is not applicable to cases where

halakha is misrepresented so as to prevent future violations of Jewish law. Other scholars argue that the dispensation to modify the truth in order to maintain peace (

me-shanim mi-penei ha-shalom,

Yevamot 65b

) also applies to misrepresenting

halakha in order to maintain peace between

kelal Yisrael and the Almighty. Yet others maintain that if a

posek believes an action should be prohibited because of

mi-gdar milta, he may misrepresent the reason for or source of a prohibition; since there will be no change in the legal outcome,

mi-devar sheker tirhak does not apply.[12] Finally, some have argued that

mi-devar sheker tirhak only refers to lying in court.[13]

But these arguments have been seriously and vigorously challenged. Thus, R. Joshua Menahem Mendel Ehrenberg[14] demonstrates that the consensus of posekim – rishonim and aharonim – is that mi-devar sheker tirhak applies in all cases, inside court and out. R. Ehrenberg further argues that this is true even if it is intended to promote a religious purpose (ve-afilu li-devar mitsva). Similarly, R. Elijah [ben Samuel] of Lublin[15] chastises a colleague for lying in a decision, even though his intentions were noble. R. Ovadiah Yosef[16] discusses at length whether a judge, maintaining a minority position on a three judge panel, can lie and say “I do not know what to rule,” – so that two more judges will be added to the panel and his minority opinion will have a chance to become the majority view; he concludes that it is forbidden. R. Solomon Sobel[17] explicitly states that me-shanim mi-penei ha-shalom only allows one to change the facts, not the halakha. Both R. Jacob Ettlinger and R. Reuben Margaliot[18] maintain that me-shanim mi-penei ha-shalom allows one only to obfuscate by using language which can be understood in different ways, but not to lie; hence, misrepresenting halakhic reasons or sources would also be forbidden.

Also unmentioned is the long list of posekim (including the Radba”z)[19] who maintain that even if one is theoretically permitted to misrepresent Halakha, under certain unique circumstances – one is nevertheless forbidden to do so in practice. This is because “the truth will out.” Not only will this revelation ultimately lead to a terrible hillul Hashem, but it will undermine peoples’ trust in the rabbinic establishment. In this regard R. Benjamin Lau has observed:[20]

The rabbi is expected to know and present the various aspects of each issue and not to conceal those aspects that are inconsistent with his own point of view. If a rabbi is untrue to the sources and reaches his decision without taking account of conflicting views, he will be seen to be untrustworthy. And a lack of trust between a rabbi and his community of questioners will drive a wedge between that community and the Torah overall. Stating the truth, of course, does not require the decisor to remain neutral; his role requires him to reach a decision one way or the other. But the decision must be reached through disclosure, not concealment, of the alternatives….. Now, when everyone has access to the [Bar Ilan] Responsa Project data base and Google provides answers to all imaginable questions, everyone can check every responsum and examine its trustworthiness. A rabbi who rules in an oversimplified way, whether strictly or leniently, in a area of halakhic complexity will be caught as untrustworthy.

Having lived through the crises and confrontations of women’s prayer groups, women on religious councils, women in communal leadership roles and women’s aliyyot – I can testify that there is great need for both in-depth knowledge and truthfulness. The “hillul Hashem and loss of trust” argument is not just hype – but painfully all too accurate! Many of the rabbis in the 1970s lost control of the religious leadership of their communities because they were unprepared or unwilling to deal with the challenges honestly and head on. Many rabbis simply tried to stonewall the situation, while others were not forthright about the real reason for forbidding such practices. As previously noted, the Rabbis may well have been correct that many of the feminist practices introduced were halakhically unsound or “bad for the Jews” on a variety of public policy grounds.[21] But instead of saying so clearly (as Rav Joseph B. Soloveitchik zt”l had urged and himself practiced), some rabbis waffled, while others prevaricated. But the halakhic truth quickly became known – a consequence of the “information age.” And as a result, many balebatim lost trust in the religious leadership as a whole. For them the conclusion was simply: “Everything boils down to politics.”

It is, therefore, critically important to reiterate that the cases cited by our author, exemplify neither pesak in general, nor the consensus view of the posekim. It is forbidden to misrepresent in halakhic rulings as a matter of law and policy. In essence, then, Prof Shapiro’s scholarly and well-documented book presents the reader with a most fascinating review of an approach within halakhic decision making, which has been rejected by mainstream pesak. Indeed, such cases need to be actively addressed if they are to be uprooted.

Response by Marc B. Shapiro

I understand why Professor Frimer is troubled by what I wrote, and to a large extent my conclusions diverge from his own. All I would say is that the matter is complex, and rather than attempt to simplify matters, as I feel Frimer has done, we must attempt to understand how the same Sages who spoke about the importance of truth could at times countenance departure from it. This is a challenge that requires sensitivity and nuance, and appreciation of changing times and values. When Frimer sees a text that permits false attribution, he sees prevarication and hypocrisy. But a historically attuned outlook would seek to understand rather than condemn. Ironically, it is Frimer who is judging the Sages and decisors, because if their ideas do not conform to his understanding then these ideas are regarded by him as problematic.

Thus, Frimer cites the famous 1865 pesak din of Michalowce and tells us that R. Moses Schick and R. Esriel Hildesheimer opposed it since they saw it as departing from the truth. While their position is certainly significant, what about the fact that among Hungarian rabbis they were a minority, and most of the leading Hungarian rabbis supported the pesak? How is my argument refuted by citing Rabbis Schick and Hildesheimer if they were opposed by most of their colleagues? Doesn’t the fact that most of the Hungarian rabbis opposed Rabbis Schick and Hildesheimer support my position?

As for the various rabbinic opinions cited by Frimer, I don’t deny that these opinions exist, and in my book I refer to Frimer’s famous article on women’s prayer groups in which he cites these opinions. But I also make the point that there is an alternative tradition which allows much more leeway for authorities to at times diverge from the truth. I also believe, contrary to Frimer, that this is a mainstream position. Since this position is held by R. Ovadiah Yosef and R. Hayyim Kanievsky, I don’t see how it is possible for one to state that it is not a mainstream position.

The point of the chapter, however, was not to advocate for one position or the other, but to focus on the alternative tradition, the existence of which is more or less suppressed today. I was explicit that my aim was to show how far some were willing to go in sanctioning deviations from the truth, and I indicate that there are views in opposition to these. However, my intent was to study the views of those with a “liberal” perspective on the importance of truth. It is this tradition that I wished to explore, and to rescue it, as it were, from the well-intentioned apologetics. I never state that this is the only authentic position. On the contrary, one can find the opposite perspective presented in numerous articles. This is why I thought it was important to present alternative views, from the Talmud until the present, views which I think show that there is a rabbinic conception of the Noble Lie.

I also must dispute the following statement by Frimer: “R. Joshua Menahem Mendel Ehrenberg demonstrates that the consensus of posekim – rishonim and aharonim – is that mi-devar sheker tirhak applies in all cases, inside court and out. R. Ehrenberg further argues that this is true even if it is intended to promote a religious purpose.” How can Frimer state that R. Ehrenberg “demonstrates” such a thing? What R. Ehrenberg does is present an argument, and everyone can evaluate its cogency. The fact is that numerous authorities do not accept R. Ehrenberg’s position, which means that they would not agree that he has proven his case.

To Frimer, and others like him who have the same reaction after reading chapter 7, I can only say that modern views of how to understand texts, and what we today regard as truth, cannot be used as a measure with which to judge people who lived in a very different time and had a very different understanding of these sorts of matters. It is their understanding that I seek to explore, rather than foisting my own value judgments upon them. Unlike Frimer, who is involved in halakhic writing and attempting to influence the community in religious matters, I write from a more “objective” perspective, without such concerns. As such, while Frimer wishes to “uproot” what he regards as unacceptable views of certain poskim. I seek to understand the phenomenon and to describe it.

When, on p. 284, I speak about redefining truth, I am not speaking about poskim per se but about how to understand the entire phenomenon that I have documented in the book. The question is how does the importance of truth coexist with what we have seen, and it is in this context that I discuss how truth need not be seen as equivalent to factual or historical truth.

I agree with Frimer that none of the great poskim supported lying in pesak as a normative option on a regular basis. Yet as I have already indicated, I believe that there is a tradition that allows for not being frank at certain times, when it is thought that other values are at stake. In the book I state that we should understand this position in a sympathetic fashion even if it is at odds with how today we generally approach matters.

Frimer asks how are we supposed to educate our children and students as to the importance of truth and truthfulness if what I say is correct. This is a good question with which educators need to struggle, but it is not a refutation of what I have written. If my position is correct, the world will not collapse. It will just be one more Torah matter, alongside Amalek, yefat toar, slavery, homosexuality, etc., that at certain times is not in line with contemporary values.

Here are some more comments relevant to the issue of truth.

1. Amichai Markowitz called my attention to a talmudic text that I overlooked.

Nedarim 23b states: “The Tanna has intentionally obscured the law, in order that vows should not be lightly treated.” This relates to the issue of the truth not being made available to all. See also

Kovetz Iggerot Hazon Ish, vol. 2, no. 78, that one should not reveal to the masses that the Sages forbade things that the Torah permitted.[22]

2. R. Joseph Ibn Caspi writes that at times it is appropriate for members of the intellectual elite to lie.[23] This explains how Joseph lied to his brothers when he accused them of being spies (Gen. 42:9). In support of this view Ibn Caspi cites both Maimonides and Aristotle.[24] The mention of Maimonides no doubt refers to the latter’s notion of “necessary beliefs”, but it is not clear where Ibn Caspi got his quote from Aristotle, since as far as I can determine Aristotle says no such thing.[25]

3. R. Abraham Arbel writes as follows[26]:

ואם מצא לנכון המגדל עז לשבח חכם כהרמב”ם שלא שקר והיה אמיתי, משמע דפשיטא ליה שגם אצל חכם בדרגתו אפשר למצוא שישקר משום כבודו.

R. Arbel also adds the following passage which I am sure will be very troubling to Frimer (as Frimer rejects the notion that “one sometimes needs to be careful about trusting a Posek”). R. Arbel’s words should be understood in line with the many sources I cite in the last chapter of my book.

וע”ע טהרת ישראל (סי’ קפה אות סו) בדין אשה שאמרה שהחכם טהר לה הכתם ועתה מכחיש אותה החכם לומר שלא שאלה אותו, דחישינן שהחכם רואה עתה שטעה שטהר, ובוש לומר שטעה, ולכן משקר עתה לומר שלא שאלה אותו. וכ”כ בהפלאה (קונ’ אחרון סי קטו סק”א( שהחכם לא נאמן להכחיש אשה, שאומרת שהחכם טהר, כשהכתם לפנינו והוא טמא, שהרי הוא נוגע בדבר שהרי טעה.

4. R. Ovadiah Yosef stated that if X tells you something he wrote, you can tell others that you read it in X’s book, and this is not considered a lie.[27]

5. In Changing the Immutable, p. 253, I cite a passage from Devarim Rabbah which states that for the sake of peace, even “Scripture itself” recorded something false. I should have also cited Midrash Tanhuma 96:7, which is even more striking, attributing the falsehood directly to God (as opposed to merely speaking of “Scripture”):

ארשב”ג גדול הוא השלום שהכתיב [שכתב] הקב”ה דברים בתורה שלא היו אלא בשביל השלום.

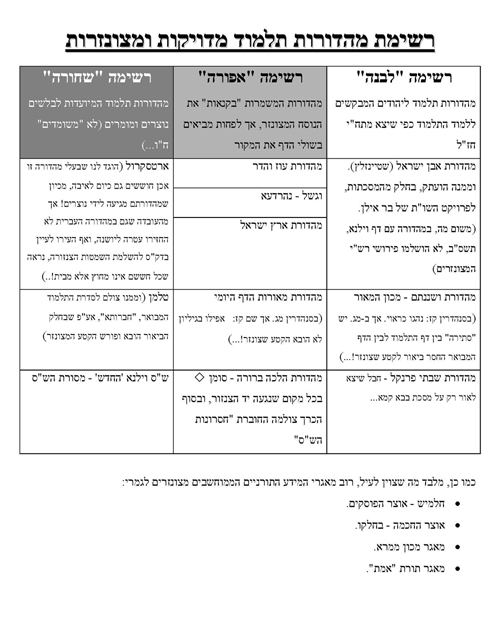

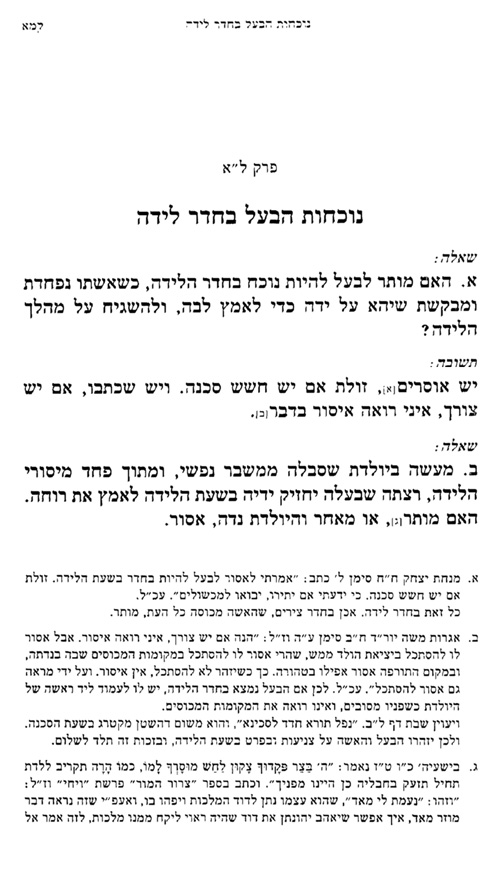

6. Let me offer another example of censorship in halakhic matters, the sort of thing that Frimer claims must be battled against and “uprooted” for the sake of Torah truth.[28] Here is page 141 from R. Yitzhak Zilberstein’s and R. Moshe Rothschild’s

Torat ha-Yoledet.

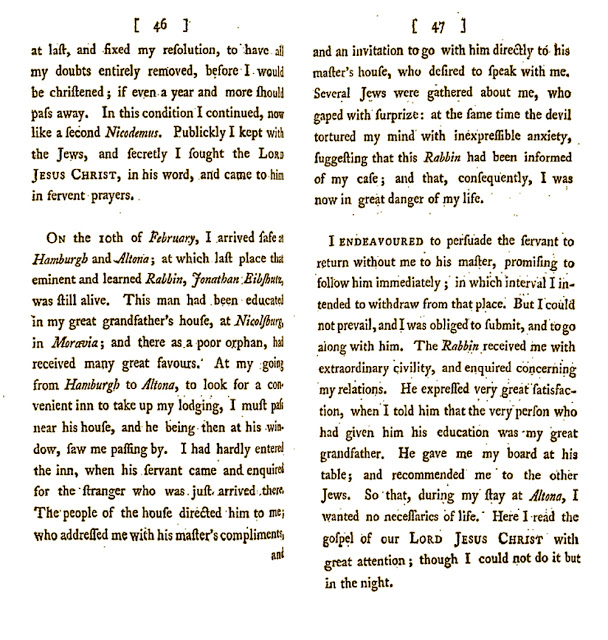

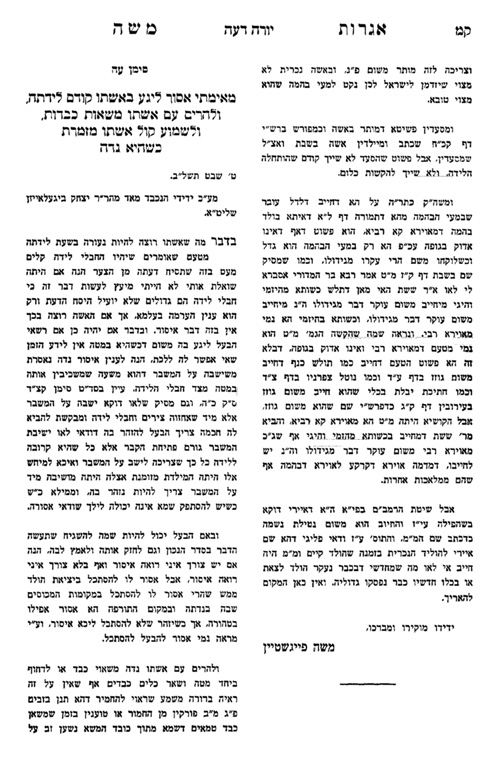

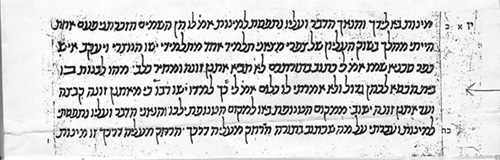

The matter dealt with is whether a husband can be in the delivery room. The authors quote the opinion that if there is a need the husband can be in the room. In note 2, R. Moshe Feinstein, Iggerot Moshe, Yoreh Deah II, no. 75, is quoted as follows:

הנה אם יש צורך, איני רואה איסור. אבל אסור לו להסתכל ביציאת הולד ממש . . .

However, if you look at the actual text of Iggerot Moshe, what he says is something different.

הנה אם יש צורך איני רואה איסור ואף בלא צורך איני רואה איסור, אבל אסור לו להסתכל ביציאת הולד ממש . . .

I have underlined the words that are deleted by

Torat ha-Yoledet. This deletion allows them to present R. Moshe Feinstein as saying that only if there is a need for the husband to be in the room can be there. Yet R. Moshe explicitly states that even if there is no “need”, he can still remain with his wife.

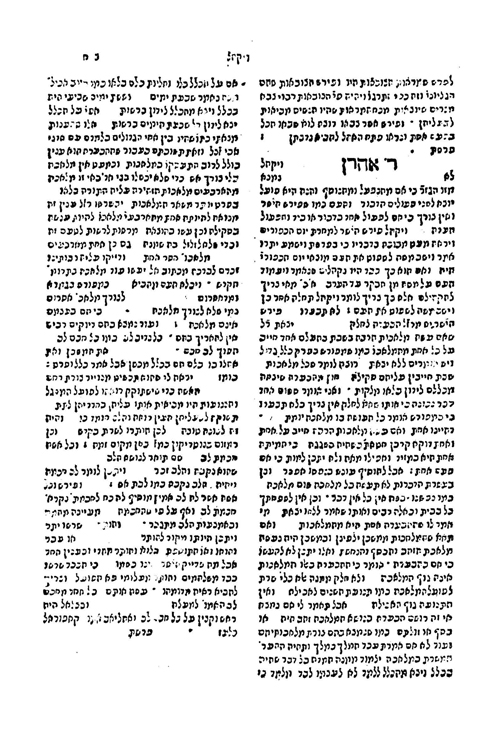

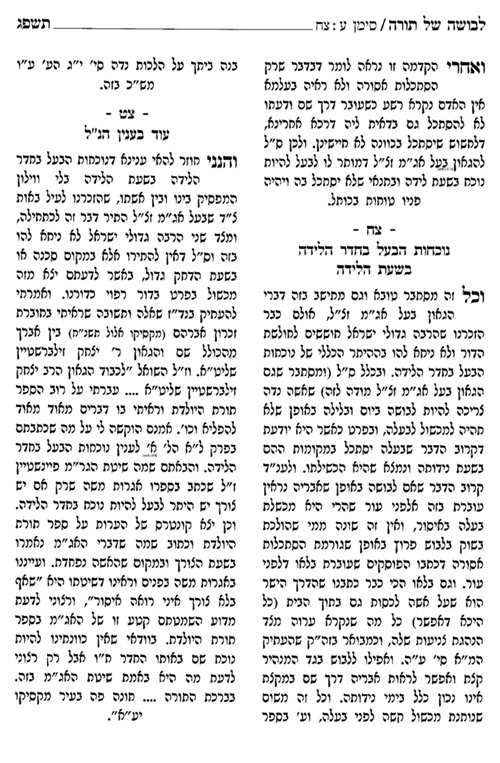

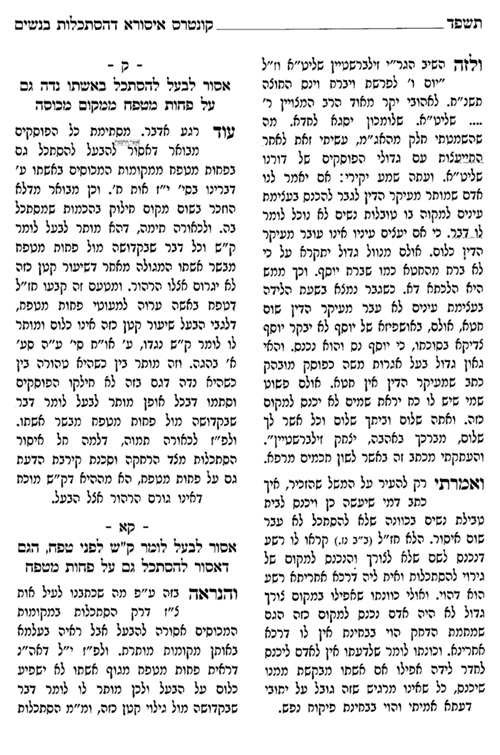

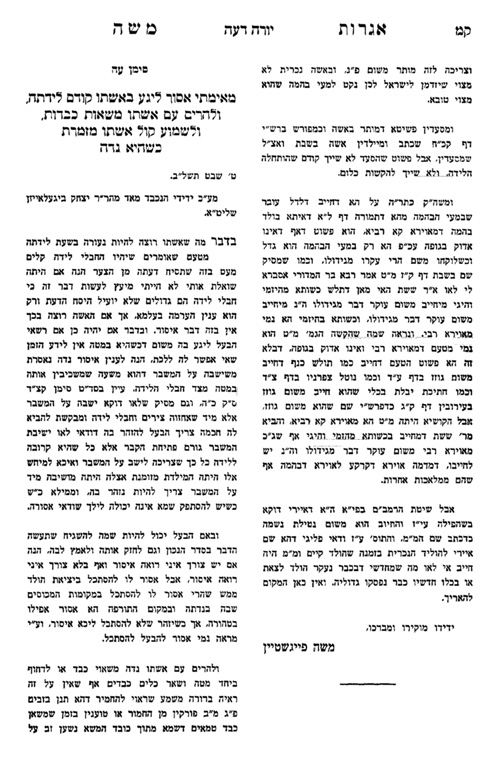

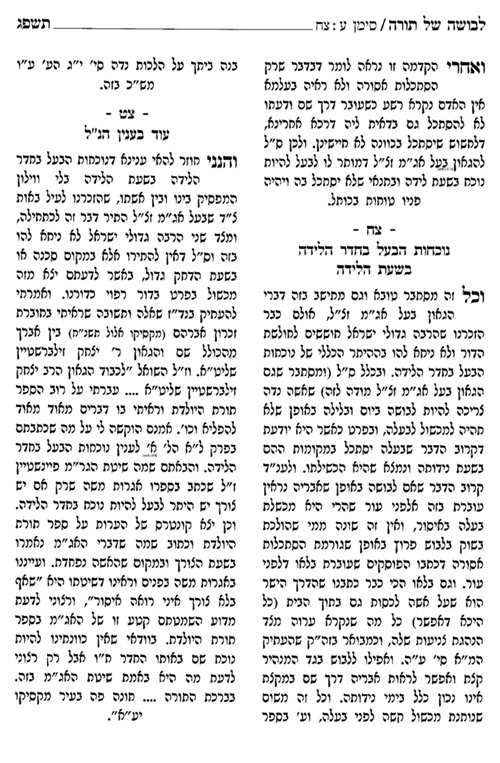

I know that there are some who are thinking that I am making a big deal out of nothing, and that it must have been an accident that the words were deleted as that no one would dare to purposely alter what R. Moshe wrote. I am sorry to say that this is not the case. Here are two pages from R. Pesach Eliyahu Falk’s Levushah shel Torah.[29]

From it we see that someone asked R. Zilberstein about the words that were deleted, and R. Zilberstein did not say that they were deleted in error. On the contrary, he tells the questioner that the words were deleted on purpose, after consultation with “gedolei ha-poskim”. In other words, these poskim disagreed with R. Moshe and therefore instructed R. Zilberstein that when he quoted Iggerot Moshe he should censor R. Moshe’s words so that people should not learn the extent of R. Moshe’s lenient view. After all that I have written in my book, I don’t think people will be surprised by this. Frimer, however, who has assured us that this sort of thing is not “mainstream”, and indeed is “forbidden”, will have to explain how it is that a respected posek like R. Zilberstein, acting on the instruction of other great poskim, could adopt such an approach, an approach which stands as a refutation of Frimer’s point.

As I have said already, I am not claiming that this sort of distortion is an everyday phenomenon. But I do claim that many poskim believe that they have the authority to alter the truth when they think that this is necessary. We can’t pretend that the texts I have cited don’t exist.

7. In his post Frimer writes: “R. Elijah [ben Samuel] of Lublin chastises a colleague for lying in a decision, even though his intentions were noble.” I don’t think the word “chastises” is appropriate in this case. R. Elijah disagrees with the other rabbi, but the disagreement is not strident. For example, R. Elijah writes as follows in Yad Eliyahu, no. 62:

ע”ד אשר האריך רום מעלתו בלשונו בשפת אמת להעמיד שפת שקר במקומי אני עומד שאינו כדאי להיות רגיל בכך ואף שמותר בו מאיזה טעם שיהיה.

8. In the next issue of

Masorah le-Yosef my article on “necessary beliefs” will appear. In this article I discuss how Maimonides and other figures say things that do not reflect their true opinion, but are merely “necessary beliefs”, i.e., “beliefs” that the masses should accept but which are not really true at all. If these authorities think that the masses can be fed false ideas when it comes to theology, why should halakhah be any different?

9. See R. Mordechai Eliasburg, Shevil ha-Zahav (Warsaw, 1897), p. 27-28, who claims that both Nahmanides and R. Jacob Emden recorded things in their writings that they did not really believe.

10. R. Chaim Sunitzky called my attention to R. Israel Weltz, Divrei Yisrael, vol. 3, no. 170, who doesn’t see such a problem with false stories if they lead people in a good direction.

.אין זה נורא כ”כ בספורי מעשיות כאלה כשהכוונה היא לטובה ללמוד ממנה מוסר ודרכי הי”ת

And now for some comic relief. A few weeks ago Ezra Glinter reviewed my book for the

Forward. See

here.

He used this opportunity to take some hits at the haredi world, focusing on matters that are not mentioned in the book. Rabbi Avi Shafran, who is paid to respond to this sort of thing, penned his own piece for the

Forward available

here.

The comedy starts in the first two paragraphs which read:

Psst! I’ve got a secret to share. It’s from deep inside the Orthodox Jewish world. Come closer… Okay, here it is: Orthodoxy changes!

It’s not much of a secret, actually. At least in these here parts. But it seems to be an unfamiliar concept for Marc Shapiro, a University of Scranton professor and author of the recent book, “Changing the Immutable: How Orthodox Judaism Rewrites Its History.”

It is obvious that Shafran has never even looked at my book and is only basing his comments on what appears in Glinter’s review. Those who have read the book know that a major theme of it is precisely how Orthodoxy changes. In fact, there is no one in the world today whose scholarship is more associated with the thesis that Orthodoxy changes than me. Much of the criticism of me is on precisely this point, that I have exaggerated the amount of change. Yet here Shafran comes and says that I am ignorant about how Orthodoxy changes. This is what I mean by comic relief.

Shafran then writes:

If a biography of Bertrand Russell can choose to elide the great philosopher’s serial marital infidelities and not be accused of rewriting the past, a hagiography of a great rabbi should certainly be permitted to overlook judgments he made with the best of intentions that in retrospect might seem misguided to some today. Such acts of civility are at times portrayed as scandalous by Shapiro and his reviewer.

A biography of Russel that chooses to omit his marital infidelities would indeed be rightly accused of rewriting the past. As for the second part of the sentence, I agree that a hagiography can leave out material of the sort Shafran mentions, but that is because it is a hagiography! If it intended to be a biography, then no, it cannot overlook mistaken judgments made by the subject, or else it ceases to be biography. I also do not think that it is an act of civility to refrain from writing about such mistaken judgments (as for example, R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg’s early misjudgment of the Nazi regime).

Shafran provides a few examples of how practice in Orthodoxy has changed, none of which I disagree with. But then again, my book has nothing to do with this. He writes:

One opinion in the Talmud, for example, permits fowl and milk to be cooked together and eaten. Just try ordering milk-braised chicken in your local kosher eatery these days; they’ll sic the mashgiach on you in a Borough Park moment. Men using mirrors was once forbidden as a “womanly” act, a once-true assessment that, for most Orthodox men today, is no longer considered applicable.

Let us say that a new edition of the Talmud was published that deleted the lines that tell us that one opinion permitted fowl and milk to be cooked and eaten together? Would Shafran be OK with this? I assume not, and it is thus unfortunate that he doesn’t know that it is precisely this sort of censorship that my book is focused on. What we have here is not only criticism without having read the book, but criticism without having any clue as to what the book is about.

And then, to top off the comic relief, Shafran ends his piece as follows:

“Why is that so hard for Orthodoxy’s critics to understand?”

I have been called some different things in my life, but this is the first time I have been referred to as one of “Orthodoxy’s critics”.

Let me also add that Changing the Immutable has sold very well in the haredi world, and this is not surprising since it is not an anti-haredi book at all.

[19] R. Yehuda Herzl Henkin, Resp. Benei Vanim, I, sec. 37, no. 12, argues that such misrepresentation most often results in gossip, hate, unlawful leniencies in other areas, hillul Hashem, and a total loss of trust in rabbinic authority should the truth become known. (This despite the fact that R. Y.H. Henkin maintains that when a posek upgrades a prohibition for a just cause, there is no prohibition of either bal Tosif or lying). Similar views are expressed by Resp. Torah liShma, sec. 371; R. Moses Jehiel Weiss, Beit Yehezkel, p. 77; R. Abraham Isaac haKohen Kook, Orah Mishpat, no. 111 (pp. 117-120) and 112 (pp. 120-129); R. Joseph Elijah Henkin, Teshuvot Ivra, sec. 52, no. 3 (in Kitvei haGri Henkin, II); R. Haim David Halevi, responsum to Aryeh A. Frimer, dated 7 Shevat 5756 – published in Resp. Mayyim Hayyim, III, sec.55; and R. David Feinstein, conversation with Aryeh A. Frimer and Dov I. Frimer, March 19, 1995. See also the commentary of Radbaz to M.T., Melakhim 6:3, where even normally permitted lying is forbidden lest it result in hillul Hashem should the truth be discovered. Similarly, in discussing Sanhedrin 29a and the cause of Adam and Eve’s sin, R. Hanokh Zundel, Eits Yosef, ad loc., s.v. “Ma,” comments that one must be particularly careful how a stringency and its rationale are formulated, for if no distinction is drawn between a stringency and the original ordinance, any error found in the stringency may lead the masses to believe that there is an error in the original ordinance itself.

[20] R. Benjamin Lau, “The Challenge of Halakhic Innovation,”

Meorot 8 Tishrei 5771, pp 43-57 at pp. 45-46, available online

here.