Nachmanides Introduced the Notion that Targum Onkelos Contains Derash

Nachmanides Introduced the Notion that Targum Onkelos Contains Derash

By Israel

Drazin

Onkelos and search it for derash, halakhah, and homiletical

teachings. The following will show that the rabbis in the Talmuds and Midrashim

and the Bible commentators who used the Targum before the thirteenth

century recognized that the Aramaic translation only contains the Torah’s peshat,

its plain meaning, and not sermonic material. It will survey how the

pre-thirteenth century rabbis and scholars used Onkelos and how

Nachmanides changed the way the Targum was understood. It was only after

this Nachmanides change that other interpreters of Onkelos read derash

into this Targum. The article also introduces the reader to Onkelos

and explains why the Talmudic rabbis required that it be read and why many

Jews failed to observe this rabbinic requirement.

Talmud and the later Jewish codes mandate that Jews read the Torah portion

weekly, twice in the original Hebrew and once in Targum Onkelos.[1]

Moses Maimonides and Josef Karo, whose law codes are regarded in many

circles as binding, felt that it is vital to understand the Bible text through

the eyes of its rabbinically accepted translation Targum Onkelos, and

many authorities agree that no other translation will do.[2]

This raises some questions.

is Targum Onkelos?

means “translation,” thus Targum Onkelos means a translation by Onkelos.

Targum Onkelos is a translation of the five books of Moses, from the

Hebrew into Aramaic. The rabbis placed their imprimatur upon Targum Onkelos[3]

and considered it the official translation. Although there are other

Aramaic translations[4]

and ancient Greek ones,[5]

and latter translations into other languages, Targum Onkelos is the most

literal. Yet despite being extremely literal, it contains over 10,000

differences from the original Hebrew text.[6]

Significance of Onkelos

extolled by all the Bible commentaries. Rashi states that the Onkelos

translation was revealed at Mt. Sinai.[7] Tosaphot[8]

made a similar statement and contends that there are places in the Torah that

simply cannot be understood without the Onkelos translation.

consider these comments as hyperbolic or metaphoric – that the authors meant

that Onkelos is so significant that it is as if it were a divine gift

handed to Moses at Sinai. But whether literal or metaphoric, it is clear that these

sages are expressing a reverence for Onkelos not accorded to any other

book in Jewish history, a reverence approaching the respect they gave to the

Torah itself. This veneration continued and is reflected in the fact that for

many centuries every printed edition of the Pentateuch contained an Onkelos

text that was generally given the preferential placement adjacent to the Torah.

did the rabbis require Jews to read Targum Onkelos?

that the Talmudic dictum was written when there were many important exegetical

rabbinical collections, the Talmuds, Genesis Rabbah, Mekhilta,

Sifra, and Sifrei, among others. Remarkably, the rabbis did not

require Jews to read these books, filled with interesting derash,

explanations written by the rabbis themselves. They only mandated the reading

of Onkelos when reviewing the weekly Torah portion.

by the time the Shulchan Arukh was composed in the sixteenth century and

the Talmudic law was stated in it, most of the classical medieval biblical

commentaries, which included derash, were already in circulation. While

Joseph Karo, its author, suggests that one could study Rashi on a weekly basis

in place of the Targum, he quickly adds that those who have “reverence

for God” will study both Rashi and Onkelos. The explanation offered by

TAZ, a commentary on the Shulchan Arukh, is that while Rashi enables the

student to read the Bible and gain access to Talmudic and Oral Law insights, Onkelos

is still indispensable for understanding the text itself.

rabbis, who composed books containing midrashic interpretations, felt that it

was so important for Jews to know the plain meaning of the Torah that they

mandated that Jews read Targum Onkelos every week.[9] When

did people stop seeing that Onkelos contains the Torah’s plain meaning

and read derash into the wording of the Targum?

problem understanding the intent of Targum Onkelos until the

thirteenth century, close to a millennium after it was composed. At that time,

Nachmanides was the first commentator to introduce the concept that people

should read Onkelos to find deeper meaning, meaning that went beyond the

plain sense of the text. These included mystical lessons, what Nachmanides

called derekh haemet, the true way.

the Torah is supported by an examination of how the ancients, living before the

thirteenth century, consistently and without exception, used Onkelos only

for its peshat. Although many of these Bible commentators were

interested in and devoted to the derash that could be derived from

biblical verses, and although they were constantly using Onkelos for its

peshat, they never employed the Targum to find derash or

to support their conclusion that the verse they were discussing contained derash.

This situation changed when for the first time Nachmanides mined the Targum to

uncover derash.[10]

Nachmanides used Onkelos to support his interpretation of the Torah.

rabbinical commentators were far more interested in derash than in peshat.

If they felt that Onkelos contained derash, they would have

used this translation, which they extolled, as Nachmanides later did, to

support their midrashic interpretations of the Torah. The following are the

ancient sources.

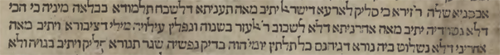

references to a Targum are in the Midrashim and the Babylonian Talmud. A

Targum is mentioned 17 times in the Midrashim[11]

and 18 times in the Babylonian Talmud.[12]

Each of the 35 quotes is an attempt to search the Targum for the meaning

of a word. Although these sources were inclined to midrashic explanations, they

never tried to draw midrashic interpretations from the Targum. Thus, the

Midrashim and the Babylonian Talmud understood that the Targum is a

translation and not a source for derash.

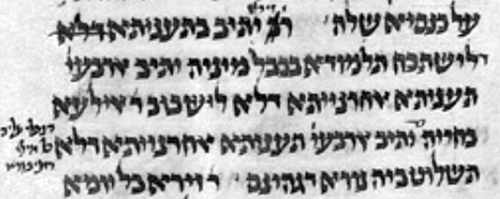

Onkelos

targumic traditions collected in Die Masorah Zum Targum Onkelos is said

to have been composed in the third century but was most likely written a couple

of centuries later,[13]

after the Talmuds. It also has no suggestion that Onkelos contains derash.

The book attempts to describe the Targum completely, but contains only

translational traditions about Onkelos. If the author(s) believed that Onkelos

has derash, he/they would have included traditions about it.

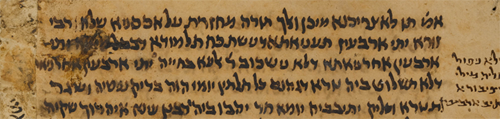

Saadiah Gaon, born in 882 C.E., also contain no indication that Onkelos has

derash. Saadiah composed a translation of the Bible into Arabic and used Targum

Onkelos extensively to discover the plain meaning of words. He never even

hinted that his predecessor’s work contains derash.[14]

This is significant since Saadiah emphasized the Torah’s plain meaning and

used Onkelos frequently in his Arabic translation.[15]

He quotes Onkelos on every page without attribution. His uses Onkelos

as a translation so extensively that if readers have difficulty

understanding Onkelos, they can look at the Saadiah translation and be

able to see what the targumist is saying.

Saruq, a tenth century Spanish lexicographer, was explicit on the subject. He

called Onkelos a ptr, a translation.[16]

Babylonian Academy at Sura in Babylonia during the years 997-1013 and wrote a

biblical commentary. He refers to Targum Onkelos on several occasions,[17]

uses the Targum to understand the meaning of words, and always treats it

as a literal translation without derash.

more on Onkelos than Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki, better known as Rashi, born

in 1040. He extols Onkelos, as stated above, mentions the targumist by

name hundreds of times,[18]

and incorporates the targumic interpretation without attribution in hundreds of

other comments. He has a non-rigid blend of peshat and derash in

his commentary,[19] and

frequently quotes the Talmuds and Midrashim as the origin of his derash.

He never uses Onkelos as a source for his derash or treats the Targum

other than as a translation. It should be obvious that since Rashi relied on Onkelos,

whom he considered holy, for peshat, if he saw derash in the Targum

he would have said so.

(also known as Rashbam, about 1085 – 1174) wrote his Bible commentary in large

measure to liberate people from derash and to show his disagreement with

Rashi’s frequent use of derash.[20]

He seldom mentions his sources, but draws from Onkelos with respect,

usually by name. In Genesis, for example, where Rashi is only named in

37:2, Onkelos is quoted in 21:16, 25:28, 26:26, 28:2, 40:11, and 41:45.

In Deuteronomy, to cite another example, Onkelos is mentioned in

4:28, 16:2, 16:9, 17:18, and 23:13. While he criticizes his grandfather with

and without attribution for his use of derash,[21]

and occasionally disagrees with Onkelos, he never rebukes the targumist

for using derash.[22]

Like his predecessors, he saw no derash in Targum Onkelos.

like Rashbam, was determined to distance himself from derash and

establish the literal meaning of the biblical text in his Bible commentaries,

as he states in his two introductions. He uses Onkelos frequently as a

translation, and only as a translation, to prove the meaning of words.

some few isolated instances of derash in the Targum. This first

observation of derash in Onkelos, I believe, is because derash

did not exist in the original Targum text.[23]

Various over-zealous well-meaning scribes embedded it at a later period,

probably around the time that Ibn Ezra discovered it. Ibn Ezra recognizes that Onkelos’

purpose is to offer peshat because he states that the targumist is

following his (ibn Ezra’s) own method, the “straight (or right) way” of peshat

to interpret the Hebrew according to grammatical rules.[24]

thereafter, Maimonides, born in 1138, supported part of his rationalistic

philosophy by using Onkelos. Maimonides recognized that the targumist

deviated frequently from a literal rendering of the biblical text to remove

anthropomorphism and anthropopathisms to avoid portraying God in a human

fashion, for this is “a fundamental element in our faith, and the comprehension

of which is not easy for the common people.”[25]

Maimonides never uses Onkelos for derash.

Joseph Bechor Schor

Joseph Bechor Schor (born around 1140) adopted the literal methodology of Rashbam.[26] However, he is not as consistent as Rashbam. He inserts homiletical comments along with those that are literal. He mentions Rashbam only twice by name but quotes Onkelos dozens of times to support his own definition of a word when his interpretation is literal. Although he used Onkelos and derash, he never states or even suggests that Onkelos contains derash [27] and never uses Onkelos to support his homiletical remarks.

(known as Radak, about 1160 – 1235) wrote biblical commentaries using the

text’s plain sense in contrast to the homiletical elaborations that were

prevalent during his lifetime. He followed the methodology of ibn Ezra and

stressed philological analysis. He refers to Onkelos frequently and

always treats the Targum as a translation. He, like ibn Ezra,

occasionally inserted homiletical interpretations into his commentary from

midrashic legends to add zest and delight readers, but he never used Onkelos

for this purpose.

Conclusion from Reading the Ancient

Commentators

history of all the commentators using Onkelos only for the plain

meaning of the Torah and never mentioning seeing derash in the Targum

is quite persuasive that no derash was in the original Onkelos

text. If any of the commentators who lived before the mid-thirteenth

century believed that Targum Onkelos contained derash, especially

those who delighted in or who were concerned with derash, they would

have said so. None but ibn Ezra did, and he called attention to only a very

small number of probably recent unauthorized insertions.

that many people today think that they see in Targum Onkelos come from?

First of all, I am convinced that most of the targumic readings that

individuals read as derash were really intended by the targumist as peshat,

the text’s simple meaning; people differ is what they see. Second, Ch. Heller

has shown us many examples where most, if not all, of the presently found derash

did not exist in the original Targum text.[28]

His findings are supported by the previously mentioned history showing that ibn

Ezra was the first to observe any derash at all in our Targum.

influenced by kabala, Jewish mysticism. He equated kabala with truth[29]

and felt[30] that

since Torah is truth, it must contain kabala. He stated that no one can attain

knowledge of the Torah, or truth, by his own reasoning. A person must listen to

a kabalist who received the truth from another kabalist, generation after

generation, back to Moses who heard the kabalistic teaching from God.[31]

He decided to disseminate this truth, or at least hint of its existence, and

was the first to introduce mystic teachings of the Torah into a biblical

commentary.[32]

exegetical methodology into his interpretations of our Targum.[33]

He felt this was appropriate. Onkelos, he erroneously believed, “lived

in the age of the philosophers immediately after Aristotle,” and like the

philosopher was so interested in esoteric teachings that, though born a high

placed Roman non-Jew, he converted to Judaism to learn Torah and later teach

its secret lessons through his biblical translation.[34]

problematical interpretations of Onkelos

which is still in draft, I studied all the instances where Nachmanides interprets

Onkelos. I found that Nachmanides mentions Targum Onkelos in his Commentary

to the Pentateuch while analyzing 230 verses. Most of his attempts to

see the targumist teaching homiletical lessons and mysticism seem forced. He

reads more into the Aramaic than the words themselves state.

interpretations of Onkelos in these 230 verses. This represents about 56

percent of the total 230. However, 55 of the 230 Nachmanidean comments are only

references to the Targum without any analysis. When these 55 comments

are subtracted from the total of 230, we are left with 175 times that

Nachmanides analyzes the Targum. The 129 problematical interpretations

represent about 75 percent of the 175 times that the sage discusses Onkelos and

uses it to support his interpretation of the biblical verse. The following are

seven examples.

God saw everything that He made, and, behold, it was very good (Torah: tov

meod – Onkelos: takin lachada).”

describes the results of the sixth day of creation as “very good.” The Onkelos

translator, who prefers to clarify ambiguous biblical phrases with more

specificity (good is which way), renders it “well established,” implying that

the world was established firmly. He may have recalled Psalms 93:1, “the

world also is established that it can not be moved” and Psalms 96:10,

“the world also shall be established that it shall not be moved.”

reads into the Onkelos words “well established” than the targumist is teaching

that creation contains evil, “the order (of the world) was very properly

arranged that evil is needed to preserve what is good.”[35]

This interpretation is a good homily, but is not the plain meaning of the

verse. It is problematical because “well established” does not suggest “containing

evil,” nor does it imply that evil is necessary to preserve what is good.

God, according to Genesis 2:7, “breathed into his nostrils the breath of

life, and man became a living being.” The bible uses nefesh for “breath”

and “being.” In later Hebrew, nefesh came to mean “soul,” a meaning it

did not have in the Pentateuch. Since the Hebrew “breath of life” does not

indicate how humans excel other creations, Onkelos alters the text and

clarifies that “man acquired the power of speech,” ruach memalela

(literally, “speaking breath”). Thus humans transcend animals by their

intelligence in general and their ability to speak, communicate, and reason in

particular. This is the Aristotelian concept, accepted by Moses Maimonides

(1138-1204), that the essence of a human is intelligence and people have a duty

to develop that intelligence.[36]

with Maimonides, the rationalist, and interprets the biblical nefesh

anachronistically as “soul.” The Hebrew verse, he declares, alludes to the

superiority of the soul that is composed of three forces: growth, movement, and

rationality.[37] Onkelos,

he maintains, is reflecting this concept of the tri-partite soul and that the

rational soul that God breathed into man’s nostrils became a speaking soul. How

the two Aramaic words, literally meaning “speaking breath,” suggests this

elaborate tri-partite theology is problematical. Again, Nachmanides seemingly

desired to have Onkelos, which he admired, reflect his own idea even

though what he reads into the Targum is not its plain meaning.

when Eve gave birth to Cain, she exclaimed, “I have acquired a man with the

Lord.” Since this statement has an anthropomorphic sound, suggesting physical

help from God, our Targum adds qadam, “before (the Lord),”

thereby supplanting, or at least softening this implication of physical aid by

distancing God from the birth.

was inserted in Onkelos in verse 4, and in seventy other instances in Genesis

for the same reason as well as 585 additional times in the other volumes of Targum

Onkelos to the Pentateuch.[38]

Nachmanides ignores the targumist’s frequent use of qadam to avoid

anthropomorphism[39] and its

plain meaning. He states that the correct interpretation of the biblical Hebrew

is that Eve said: “This son will be an acquisition from God for me, for when we

die he will exist in our place to worship his creator.” Nachmanides assures us

that this is Onkelos’ opinion as proven by the addition of the word qadam.

Thus, Nachmanides drew a conclusion from the Targum’s single word, a

word that is used over five hundred times for an entirely different purpose and

which cannot, by itself, connote and support his interpretation. Furthermore, qadam

does not have this meaning in the hundreds of other instances where it

appears.

changes a significant detail in the Aramaic translation. Abraham does not

“laugh” (Hebrew, vayitzchak) when he hears he will have a child in his

old age, but “rejoices” (Aramaic, vachadi). This alteration is not made

in 18:12 where Sarah “laughed” when she heard the same news. Rashi explains

that the couple reacted differently. Abraham trusted God and rejoiced at the

good news, while Sarah lacked trust and sneered; therefore God chastised her in

18:13.

states that Onkelos’ rendering in 17:17 is correct because the word tzachak

also means “rejoice,” and Abraham and Sarah’s reactions, he contends, were the

same, proper “rejoicing.”

defined by ibn Shoshan and others, tzachak is an outward expression, a

“laugh,” and not an inner feeling of contentment. Bachya ben Asher mentions the

Aramaic rendering, but he does not mention Nachmanides. He recognizes, contrary

to Nachmanides, that tzachak does not mean “rejoice,” but “laugh.” He

states that the targumist made the change to “rejoices” because in the context

in which the word appears here it should be understood as an expression of joy.

This example, while not expressing a theology, as in the first three instances,

also shows Nachmanides insisting by a forced interpretation that the targumist

is understanding the Torah as he does.

replaces the Torah’s “Is anything too wondrous for the Lord,” in Genesis

18:14, with “Is anything hidden from before the Lord.” The Hebrew “wondrous” is

somewhat vague and is seemingly not exactly on point with the tale of Sarah’s

laughter. The Aramaic explains the text and relates that Sarah’s laughter,

mentioned in the prior verse, although it was not done openly, was not “hidden”

from God. This is also the interpretation of Saadiah, Rashi, Chazkunee, ibn

Ezra, Radak, etc. Thus, in short, all that the targumist is doing is clarifying

the text, a task he performs over a thousand times in his translation.

Nachmanides states that Onkelos uses “hidden” in the translation to teach a

mystical lesson. Nachmanides, as generally happens, does not explain the

lesson, but the explanation is in Bachya ben Asher and Recanati. Bachya writes

that God added the letter hay to Abram’s name, turning it into Abraham,

and “the letter hay alludes to God’s transcendental powers”; thus God

gave Abraham the power to have a son. Abraham, he continues, exemplified the

divine attribute of mercy and Isaac the divine attribute of justice, and now

both attributes would exist on earth. It is difficult if not impossible to read

this Nachmanidean mystical interpretation of Onkelos into the word

“hidden.”[40]

21:7 quotes Sarah’s excited exclamation of joy:[41]

“Who (meaning which person) would have said to Abraham” that I would give birth

at the advanced age of ninety. The Targum renders her statement as a

thankful praise of God: “Faithful is He

who said to Abraham,” and avoids the risk of the general population reading the

translation and misunderstanding Sarah’s reaction as one of surprise, for she

should not have been surprised. God had assured Abraham that he would have a

son a year previously.[42]

Thus, by making the change, the Targum shows that she is not only not

surprised, but is thankful that God fulfilled His prior promise.

interprets the Torah’s “Who would have said to Abraham” to mean that everyone

will join Abraham and Sarah and rejoice with them over Isaac’s birth because it

is such a “surprise”; the possibility of the birth would never have occurred to

anyone. He writes that Onkelos’ rendition is “close” to his

interpretation of a community celebration. Actually as we stated, Onkelos’

“Faithful is He who said to Abraham” is quite the opposite. Rather than

focusing on the people and the unexpected event, the targumist deviated from the

Hebrew text to avoid depicting Sarah being surprised. His Aramaic version

concentrates on God, not the community, and how the divine promise was

fulfilled.

22:2 recounts God commanding Abraham to take his son Isaac to “the land of

Moriah” and offer him there as a sacrifice. Mount Moriah was traditionally

understood to be the later place of the Jerusalem Temple[43]

and the targumist therefore renders “Mount Moriah” as “the land of worship” to

help identify the area for his readers. This is a typical targumic methodology;

the Targum changes the name of places mentioned in the Bible and gives

its later known name.[44]

contends that Onkelos is referring to a midrashic teaching that was

recorded years after the targumist’s death in Pirkei d’R. Eliezer:[45]

God pointed to the site and told Abraham that this is the place where Adam,

Cain, Abel, and Noah sacrificed, and the site was named Moriah because Moriah

is derived from the word mora, “fear,” for the people feared God there

and worshipped Him.

several problems with Nachmanides’ analysis. First, as we already pointed out,

our targumist frequently updates the name of a site to help his readers

identify its location[46]

and this is a reasonable consistent explanation of the targumic rendering.

Second, the words “land of worship” do not suggest the elaborate midrashic

story that is not recorded until long after the death of the targumist. Third,

the story is a legend; there is nothing in any text to indicate that God had

such a conversation with Abraham or that the ancestors sacrificed in this area;

and it is contrary to the targumist’s style to incorporate legends into his

translation.

if the Bible commentators before Nachmanides saw derash in Onkelos

we would have expected them to say so, but none did until Abraham ibn Ezra and

he was probably referring either to recent scribal additions to the original Targum

or he was expressing his opinion that his view of peshat on certain

verses differed with those of the targumist. Nachmanides was the first to read derash

and mysticism into the Targum just as he was the first to read

mysticism into the Torah itself. We offered some examples that show the

difficulties of his methodology.

introduction of the notion that Onkelos contains mysticism may be the

reason why rabbis,[47]

who respected Nachmanides’ teachings, began for the first time to search the Targum

for derash.

Drazin is the author of thirty-three books, including twelve on Targum Onkelos.

His website is www.booksnthoughts.com.

This article appeared previously on www.oqimta.org.il.

Mishneh Torah, Laws of Prayer 13:25, and Shulchan Arukh, Orach Chayim,

The Laws of Shabbat 285, 1. The requirement is not in the Jerusalem Talmud

because Targum Onkelos did not exist when this Talmud was composed. See

I. Drazin, Journal of Jewish Studies, volume 50, 1999, pages 246-258,

where I date Onkelos to the late fourth century, based on the

targumist’s consistent use of late fourth century Midrashim.

Arukh, discussed below, say that a person can fulfill the rabbinic

obligation by reading Rashi.

are Targum Pseudo-Jonathan and Targum Neophyti.

translation by Aquila, composed about 130 CE.

as to clarify passages, to protect God’s honor, to show respect for Israelite

ancestors, etc. These alterations were not made to teach derash, as will

be shown below. The differences between peshat and derash is a

complex subject. Simply stated, peshat is the plain or simple or obvious

meaning of a text. Derash is the reading of a passage with either a

conscious or unconscious intent to derive something from it, usually a teaching

or ruling applicable to the needs or sensibilities of the later day, something

the original writer may have never meant.

8a, b.

their derash unless they first understood the Torah’s peshat.

is also supported by the following interpretation of the Babylonian Talmud,

Megillah 3a. The Talmud recalls a

tradition that the world shuttered when Targum Jonathan to the Prophets

was written. Why, the Talmud asks, did this not occur when Targum Onkelos was

composed? Because, it answers, Onkelos reveals nothing (that is, it

contains no derash), whereas Targum Jonathan reveals secrets (by

means of its derash).

(Jerusalem, 1974), pages 225-238, and J. Reifman, Sedeh Aram (Berlin,

1875), pages 12-14. The mention of a Targum in the Midrashim and Talmuds

are not necessarily references to Onkelos; the wording in these sources

and Onkelos frequently differ.

pages 8-10.

Drazin, JJS 50.2, supra, and note 15, for a summary of the

scholarly comments on this volume.

the introduction to Onkelos on the Torah: Leviticus, pages xvii-xxii.

Mossad Harav Kook, Jerusalem, 1986, and Daf-Chen Press, Jerusalem, 1984. The

uses of Onkelos are indexed in Genesis in the 1984 volume on page

471. See E. I. J. Rosenthal, “the Study of the Bible in medieval Judaism,” Studia

Semitica, Cambridge, 1971, pages 244-271, especially pages 248 and 249

regarding Saadiah.

philology as a prerequisite for the study of the literal sense of the Bible and

he used rabbinic interpretations in his translation only when it complied with

reason. He stated at the end of his introduction to the Pentateuch that his

work is a “simple, explanatory translation of the text of the Torah, written

with the knowledge of reason and tradition.” He, along with ibn Ezra and

Onkelos, as we will see, included another meaning only when the literal

sense of the biblical text ran counter to reason or tradition. His failure to

mention that Onkelos contains derash does not prove indisputably

that he saw no derash in the commentary. However, since he copied Onkelos’

interpretations so very frequently in his Arabic translation, it is likely that

if he saw derash in Onkelos he would have mentioned it.

editor), London and Edinburgh, 1854, pages 14a, 16b 17a, 17b, 20a, and others.

Mossad Harav Kook, Jerusalem, 1978, index on page 111.

by Charles B. Chavel, Mossad Harav Kook, Jerusalem, 1982, pages 628 and 629.

For Rashi’s struggle against derash, see, for example, his commentary to

Genesis 3:8. While Rashi believed he interpreted Scriptures according to

its peshat, ibn Ezra criticized him: “He expounded the Torah

homiletically believing such to be the literal meaning, whereas his books do

not contain it except once in a thousand (times),” Safah Berurah, editor

G. Lippmann, Furth, 1839, page 5a. See also S. Kamin, Rashi’s Exegetical

Categorization with Respect to the Distinction Between Peshat and Derash

(Doctorial Theses), Jerusalem, 1978; M. Banitt, Rashi, Interpreter of the

Biblical Letter, Tel Aviv University, 1985; and Y. Rachman, Igeret Rashi,

Mizrachi, 1991.

meant that his commentary frequently contains derash that seemed to him

to reflect the plain meaning of the Torah.

on Genesis, Jewish Studies, The Edwin Mellen Press, 1989. See especially

Rashbam to Genesis 37:2 and 49:16 where he criticizes his grandfather

with strong language.

Rashi’s Torah Commentary is the primary focus of Rashbam’s own commentary. Of

some 650 periscopes of interpretation in the latter’s commentary to Genesis,

only about 33 percent concern issues not relevant to Rashi. Of the remaining

two-thirds, in only about 18 percent does Rashbam feel Rashi is correct, and in

just over 48 percent he is in disagreement with him, consistently criticizing

him for substituting derash for peshat, exactly what Rashi

declared he would not do. With this sensitivity to and opposition to derash,

it is very telling that he did not sprinkle even one drop of his venom on the

targumist.

issues the accolade: “the plain meaning of scripture is the one offered by the

Targum.” It is significant to note that although Rashbam railed against the

insertion of derash into a biblical commentary, his own commentary was

frequently adulterated, as was Targum Onkelos, by the improper

insertions of derash by later hands. See, for example, Deuteronomy

2:20, 3:23, 7:11, and 11:10 in A. I. Bromberg, Perush HaTorah leRashbam,

Tel Aviv, 5725, page 201, note 25; page 202, note 111; page 206, 7, note 9; and

page 210, note 3.

the original text of Onkelos did not have derash. However, they

did not recognize that Nachmanides was the first commentator to argue the

opposite. The first is in A Critical Essay on the Palestinian Targum to the

Pentateuch, NY, 1921, pages 32-57. The second is in Targum Yonatan al

Hatorah, New York, 5685, page 5. See also Bernard Grossfeld in “Targum

Onkelos, Halakhah and the Halakhic Midrashim,” in D.R.G. Beattie and M.

McNamara (editors), The Aramaic Bible , 1994, pages 228-46.

commentary on the Pentateuch, ibn Ezra writes that he intends to mention by

name only those authors “whose opinion I consider correct.” He names Onkelos

frequently. In his commentary to Numbers, for example, the Targum is

cited in 11:5 where he gives another interpretation, but respectfully adds, “he

is also correct,” and in 11:22 he comments, “it means exactly what the Aramaic

targumist states.” See also 12:1; 21:14; 22:24; 23:3; 23:10; 24:23 and 25:4.

Asher Weiser, Ibn Ezra, Perushei Hatorah, Mossad Harav Kook, 1977.

respectfully, ibn Ezra uses the strongly derogatory terms “deceivers” or

“liars,” for the derash-filled Targum Pseudo-Jonathan to Deuteronomy

24:6. See D. Revel, Targum Yonatan al Hatorah, New York, 5685, pages 1

and 2.

addresses is the avoidance of a literal translation of most anthropomorphic and

anthropopathic phrases. See the listing in Moses Maimonides, The Guide of

the Perplexed, translated and with an introduction by Shlomo Pines, The

University of Chicago Press, 1963, volume 2, pages 656 and 658, and 1:28 for

the quote.

interpretation of negative commands 128 and 163 in part upon our Targum.

Maimonides, The Commandments, translated by Charles B. Chavel, The

Soncino Press, 1967, pages 116, 117 and 155, 156. This was not because Onkelos

deviated from the plain meaning to teach halakhah. Command 128 forbids

an apostate Israelite to eat the Passover offering. Onkelos translates

the biblical “no alien may eat thereof” as “no apostate Israelite” (Exodus

12:43). The targumist may have thought this was the necessary meaning because Exodus

12:45 and 48 state that a sojourner and an uncircumcised Israelite could not

eat this sacrifice; thus the earlier verse must be referring to someone else.

Command 163 prohibits a priest from entering the Sanctuary with disheveled,

untrimmed hair. Maimonides notes that

Onkelos translates Leviticus

10:6’s “Let not the hair of your heads go loose” as “grow long.” Again, the

targumist may have thought that this was the verse’s simple sense because it is

the language used by the Torah itself in Numbers 6:5 and because when

one loosens one’s hair it becomes longer. Indeed, Rashi states explicitly that

the peshat of “loose” in this instance is “long.”

brother Rabbeinu Tam. See the source in the next note.

Hatorah, Mossad Harav Kook, 1994, page 11, Schor went beyond Targum

Onkelos in his concern about biblical anthropomorphisms and his attempts to

whitewash the patriarchs.

others.

truth. Kabala is truth. Thus, Torah “must” contain Kabala.

and annotated by Charles B. Chavel, Shilo, 1978, page 174.

and annotated by Charles B. Chavel, Shilo Publishing House, Inc., 1971, volume

1, XII. Chavel points out that the extensive kabalistic influences on future

generations can be traced to Nachmanides.

facts. First, we know that he was the first to read Kabala in the Torah words

and phrases. Second, we know that he had enormous respect for Onkelos;

he referred to Onkelos about 230 times in his Bible commentary; although

he criticized others, he treated Onkelos with great respect, even

reverence. He considered Onkelos to be generally expressing the

truth. Thus it is reasonable to assume that he applied the same syllogism to Onkelos

that he applied to the Torah. Finally, we know of no one before him who

read mysticism into the targumist’s words.

75-76. Nachmanides’ error in dating Targum Onkelos “immediately after

Aristotle” was not his only historical mistake. He believed that the Talmud’s

implied dating of Jesus at about 100 years before the Common Era was correct. See

Judaism on Trial, editor H. Maccoby, Associated University Presses, Inc.,

1982, pages 28 and 29.

is the source of this teaching, mentions “death” and 9:9 “the evil inclination

in man” as examples of seemingly bad things, which are good from a non-personal

world-wide perspective. Bachya ben Asher, the student of Nachmanides’ student

Rashba, who was also a mystic, mentions 9:9, but not the Targum. He did

not see this idea in Onkelos.

had a similar developmental history as the Hebrew nefesh. T. Cahill, Sailing

the Wine-Dark Sea, Doubleday, 2003, writes on page 231.

was, to begin with, a Greek word for “life,” in the sense of individual human

life, and occurs in Homer in such phrases as “to risk one’s life” and “to save

one’s life.” Homer also uses it of the ghosts of the underworld – the weak,

almost-not-there shades of those who once were men. In the works of the early

scientist-philosophers, psyche can refer to the ultimate substance, the

source of life and consciousness, the spirit of the universe. By the fifth

century B.C., psyche had come to mean the “conscious self,” the

“personality,” even the “emotional self,” and thence it quickly takes on,

especially in Plato, the meaning of “immortal self” – the soul, in contrast to

the body.

but not the Targum, again not seeing Nachmanides’ idea in Onkelos.

published by Ktav Publishing House. Each contains a listing of the deviations

by the targumist from the Hebrew original.

Nachmanides was convinced that Onkelos never deviates to avoid

anthropomorphisms.

again not seeing the Nachmanidean interpretation in the Targum.

6.

is rendered “the land of worship.” He connected “Moriah” to “myrrh,” which was

an ingredient of the sacrificial incense and an important part of the Temple

worship. Rashi states that this is the targumic interpretation. Rashi may be

explaining why the site was called Moriah, which would not be derash,

but the plain sense of the word. Nachmanides interpretation goes far beyond a

simple definition. See Genesis Rabbah 55:7, Exodus 30:23ff, and

Babylonian Talmud, Keritut 6a.

alone.

they see in Onkelos. The most widely known is Netina Lager by

Nathan Adler (Wilna, 1886). Others include Biure Onkelos by S. B.

Schefftel (Munich, 1888), and Chalifot Semalot and Lechem Vesimla by B. Z. J.

Berkowitz (Wilna, 1874 and 1843). Modern

writers using this method include Y. Maori, who generally focuses on the Peshitta

Targum, Rafael Posen who writes a weekly column for a magazine distributed

in Israeli synagogues. One can find listings in B. Grossfeld’s three volumes A

Bibliography of Targum Literature, HUC Press, 1972.