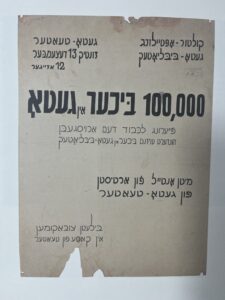

For the Sake of Radin! The Sugar Magnate’s Missing Yarmulke and a Zionist Revision

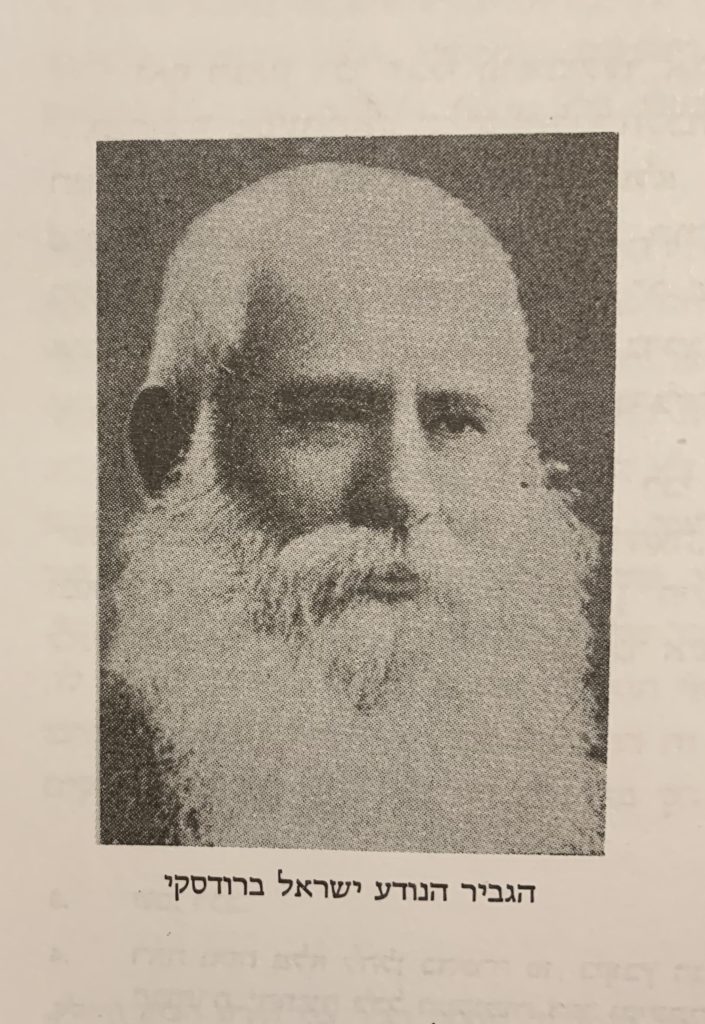

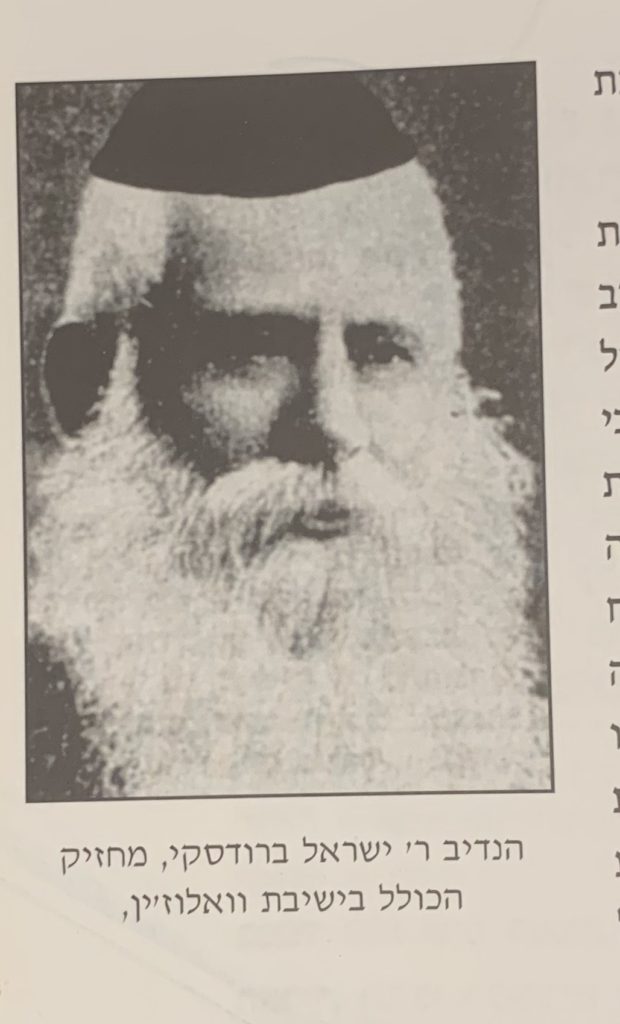

Israel Brodsky (1823-1888), built an empire on the sugar trade. After inheriting a substantial fortune, in 1843, he became a partner in a sugar refinery.[1] Eventually, he vertically integrated his business, and he controlled sugar beet lands, processing plants, refineries, marketing agencies, and warehouses throughout the Russian Empire. At its height, Brodsky controlled a quarter of all sugar production in the Empire and employed 10,000 people.[2] Brodsky sugar “was a household name from Tiflis to Bukhara to Vladivostok.”[3] Brodsky was a significant philanthropist, donating to Jewish and non-Jewish causes. In Kyiv, he and his sons virtually single-handedly founded the Jewish hospital, Jewish trade school, a free Jewish school, mikveh, and communal kitchen besides substantial individual donations, amounting to 1,000 rubles monthly, and donated to St. Vladimir University. Many of these institutions would bear the Brodsky name. Leading Shalom Aleichem to remark that the “the bible starts with the letter beyes and [Kyiv], you should excuse the comparison, also starts with beyes – for the Brodskys.” [4]

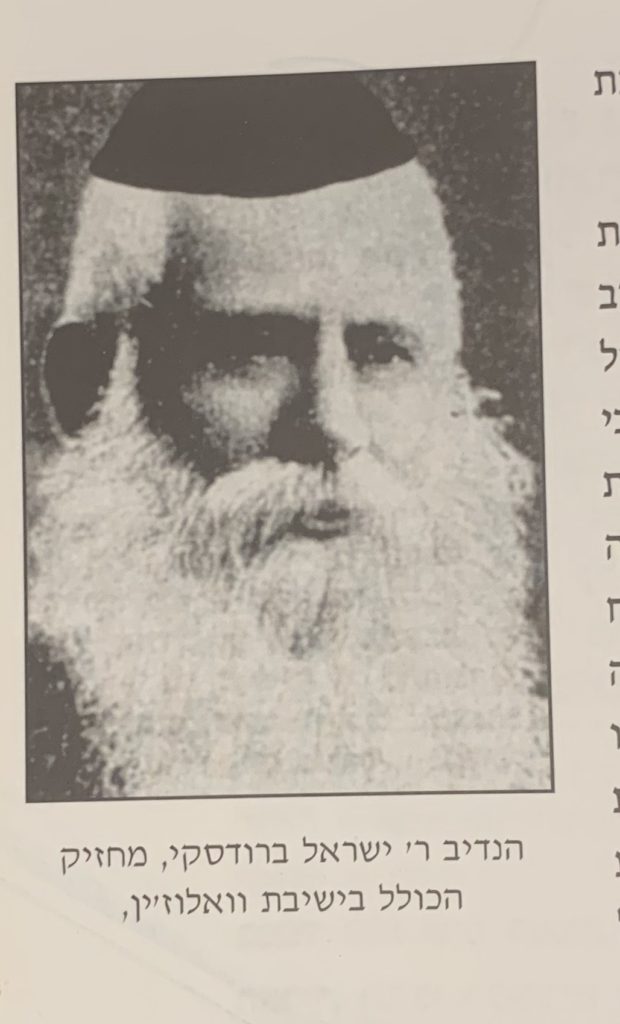

In addition to supporting local causes, he also helped other institutions outside of Kyiv. One was providing an endowment for a kolel at the Volozhin Yeshiva. The institution of the kolel, a communally subsidized institution that supported men after marriage, was originated by R. Yitzhak Yaakov Reines (1839-1915). Reines was a student of the Volozhin Yeshiva and would go on to establish the Mizrachi movement and the Lida Yeshiva, both of which were attacked by some in the Orthodox establishment.[5] Invoking the Talmudic passage Rehaim al Tsaverum ve-Yasku be-Torah?!, in 1875, he proposed an institution where “men of intellect . . . will gather to engage in God’s Torah until they are worthy and trained to be adorned with the crown of the rabbinate, that will match the glory of their community, to guide the holy flock in the ways of Torah and the fear of Heaven.” Without the communal funds, these “men of intellect” would “be torn away from the breasts of Torah because of the poverty and lack that oppresses them and their families.”[6] Reines intended that the kolel be associated with Volozhin. And, in 1878, an attempt to create such an institution began taking shape, with the idea to approach the Brodskys for funding. For reasons unknown, this never happened. Instead, through the generosity of Ovadiah Lachman of Berlin, the first kolel was established in 1880. The kolel opened not in Volozhin but Kovno. It would be another six years before Volozhin established its kolel.[7]

In 1886, Brodsky donated a substantial sum to create a kolel in Volozhin. He created an endowment fund that yielded 2,000 rubles annually. But unlike the Kovno kolel that produced some of the greatest rabbis and leaders of the next generation, according to one assessment the Volozhin kolel “had little influence on the yeshiva’s history” nor the general public.[8]

Comparing Brodsky’s donation to the kolel to that of his other contributions demonstrates that this donation was similar to his most significant gifts. His donation was in the form of stock, and while we don’t have an exact estimate of the value of those shares, we can extrapolate the total amount of Brodsky’s donations. Brodsky donated 60 shares of the Kyiv Land Bank, which was intended to produce 2,000 rubles per annum.[9] But the amount of the principle, the 60 stocks, is not provided in the source materials. In 1890, a similar endowment by the Brodskys produced 3,000 rubles annually from a principle of 50,000 rubles, a 6 percent rate of return. Assuming a similar rate of return, his initial donation to the Volozhin kolel nearly 35,000 rubles. That is the similar amount that he donated to the Kyiv free Jewish school, the St. Vladimir’s University, and Kyiv’s mikve and communal kitchen that all received 40,000-ruble bequests.[10] Consequently, Brodsky’s gift of 60 shares of stock to the Volozhin kolel is comparable to Brodsky’s other institutional donations.

The Brodskys aligned with the Russian Haskalah movement that today we would likely characterize as Modern Orthodox, although admittedly, the definitions of sects are amorphous. The Russian haskalah was notable for embracing modernity while maintaining punctilious observance of halakha. One example that involved both the intersection of society at large and religious practice was that when the Governor-General invited two of Israel’s sons to a prestigious gala at his home, the Governor-General also provided the sons with kosher food.[11] Another example of the Brodskys’ Jewish outlook was their involvement in Kyiv’s Choral Synagogue. Choral synagogues were already established in other cities throughout the Russian Empire, including Warsaw, Vilna, and St. Petersburg. The synagogue, known as the Brodsky Synagogue, was built in 1898 by Israel’s son, Lazer. Modern practices were introduced to the Kyiv Choral Synagogue, but even those are within the bounds of accepted Jewish law.[12] Indeed, those new practices are today unremarkable, hiring a hazan, incorporating a choir into the service, delivering the sermon in Russian, and enforcing decorum during the prayers.[13]

The Haredi histories of Volozhin discuss Brodsky’s contributions to the kolel. But one publication decided that his reputation needed some creative airbrushing to (presumably) make his involvement more palatable to the modern Haredi audience. Despite the fact that other Haredi publications provide an unvarnished version.

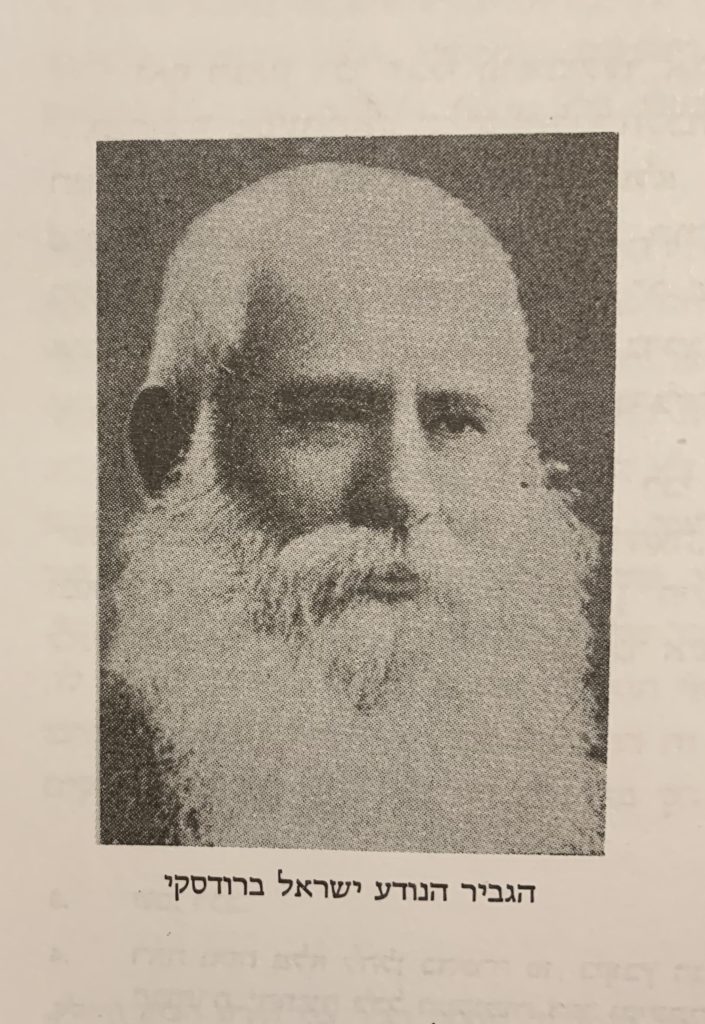

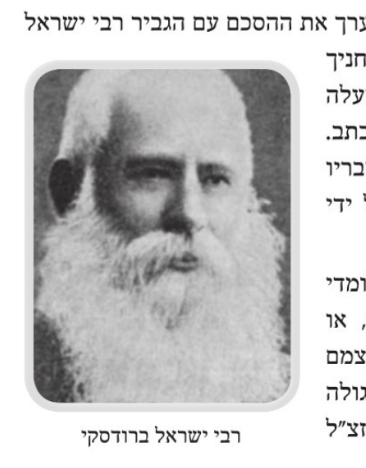

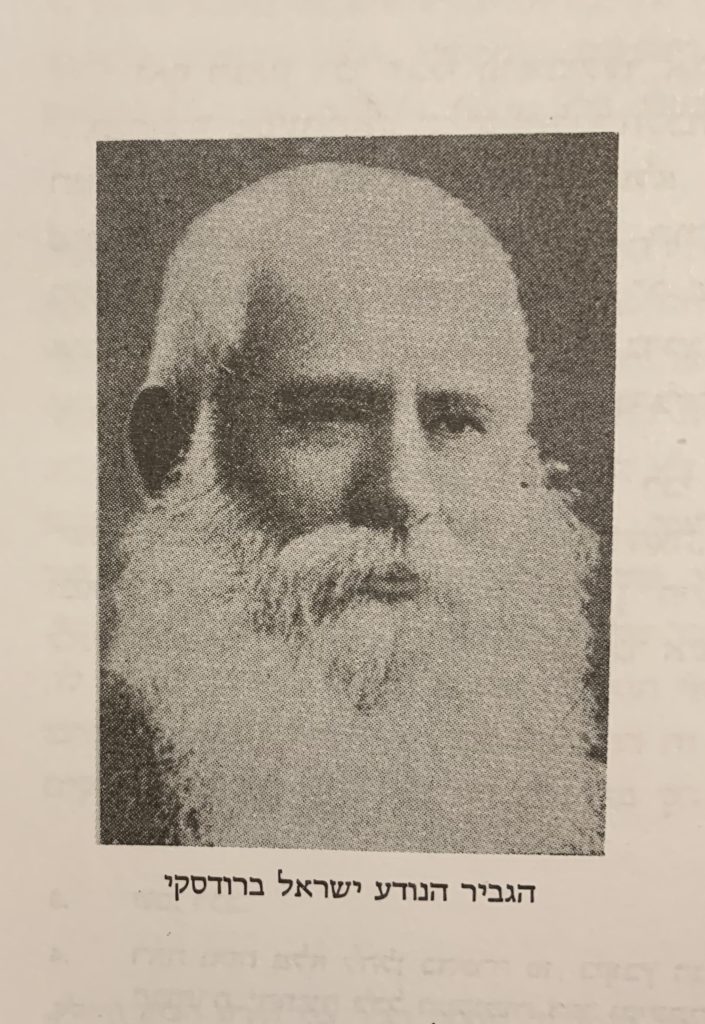

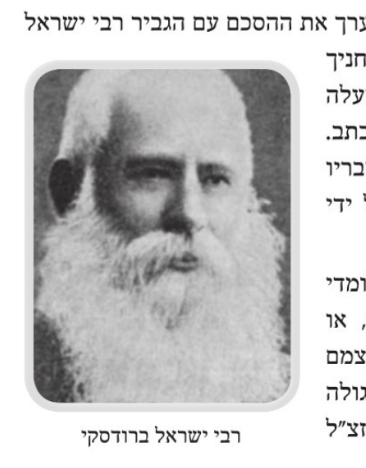

One person who met Brodsky described him as resembling that of a biblical patriarch in appearance, yet at the same time non-Jewish.[14] Indeed a photo from 1880, this biblical patriarch appears bareheaded. This lack of head-covering was not an issue for some Haredi authors. For example, Dov Eliach includes this photograph in his history of the Volozhin Yeshiva.[15] In 2001, not ten years after Eliach’s book another Haredi author decided that the photo required adjustment despite sharing the same publisher as Eliach.

Menahem Mendel Flato’s book, Besheveli Radin (Radin’s Paths), devotes an entire chapter to Brodsky’s kolel, with his photograph accompanying the text. Yet, in this instance, rather than a bareheaded Brodsky, a crudely drawn yarmulke now appears on his head.[16] This is not the first time that images were doctored to depict a yarmulke where there is none.[17] Those types of alterations occur decades after the original, by different publishing houses, in different cities, and for a different audience.[18] Here, however, Avi ha-Yeshivot and Besheveli Radin share the same audience and are only separated by ten years. [19]

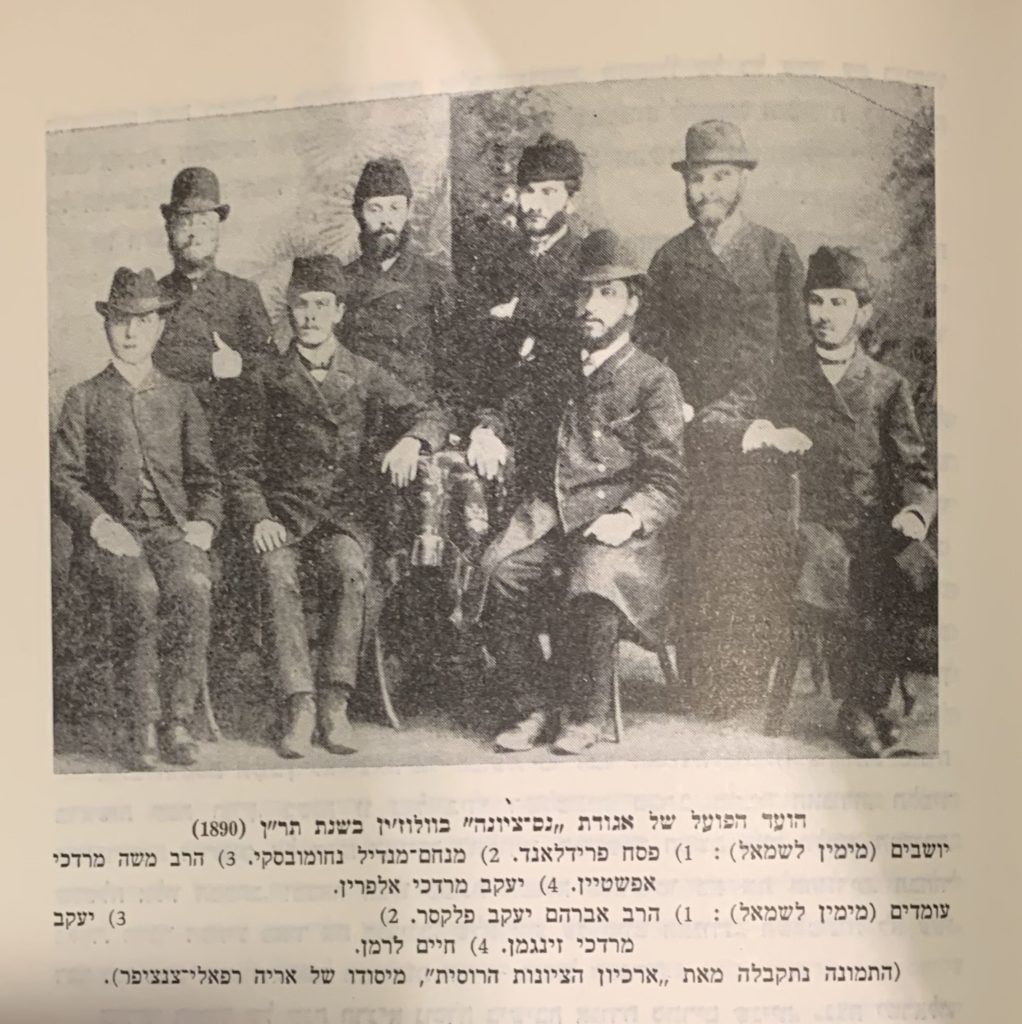

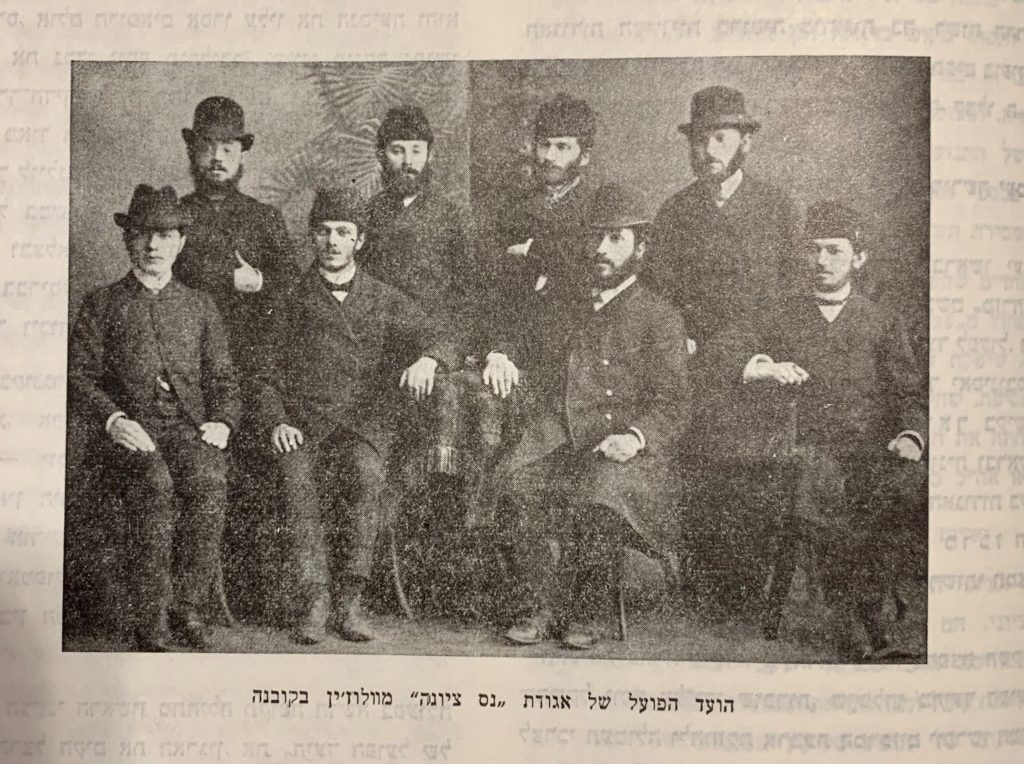

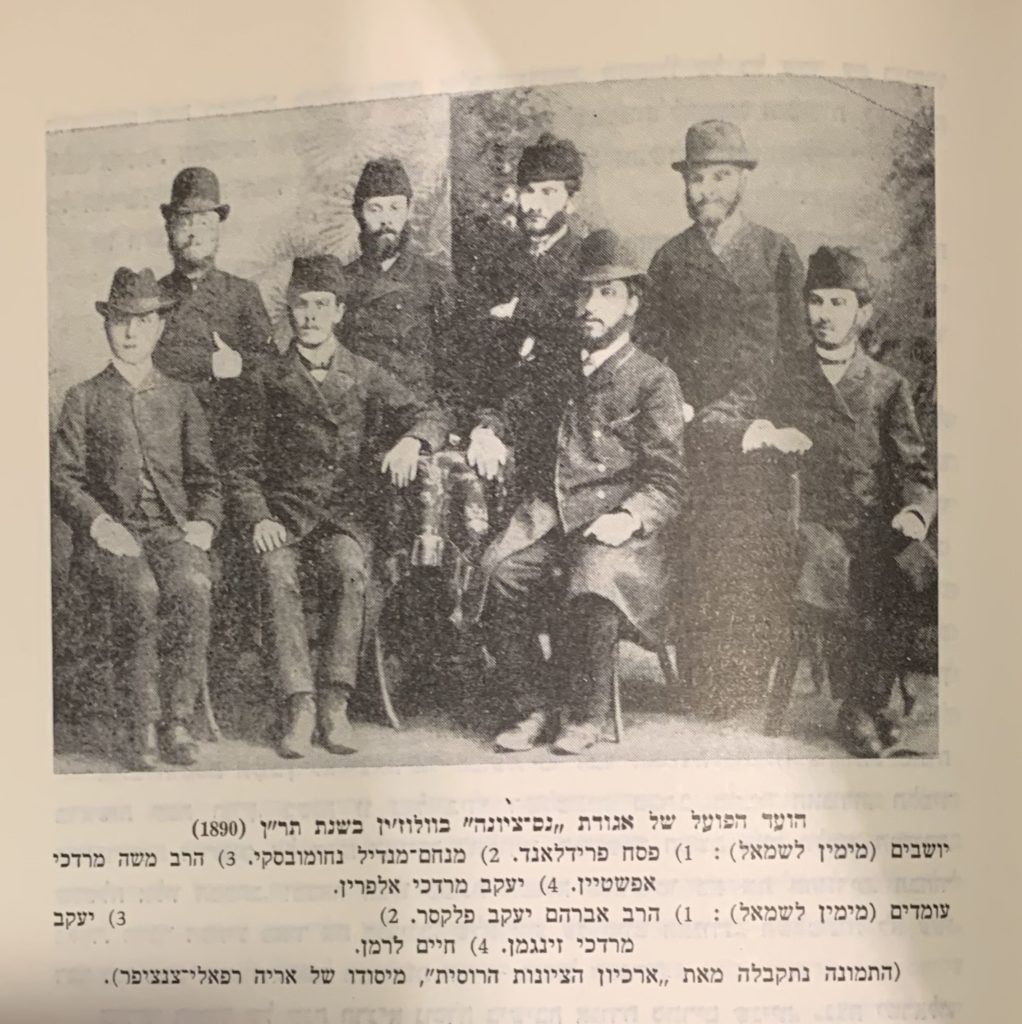

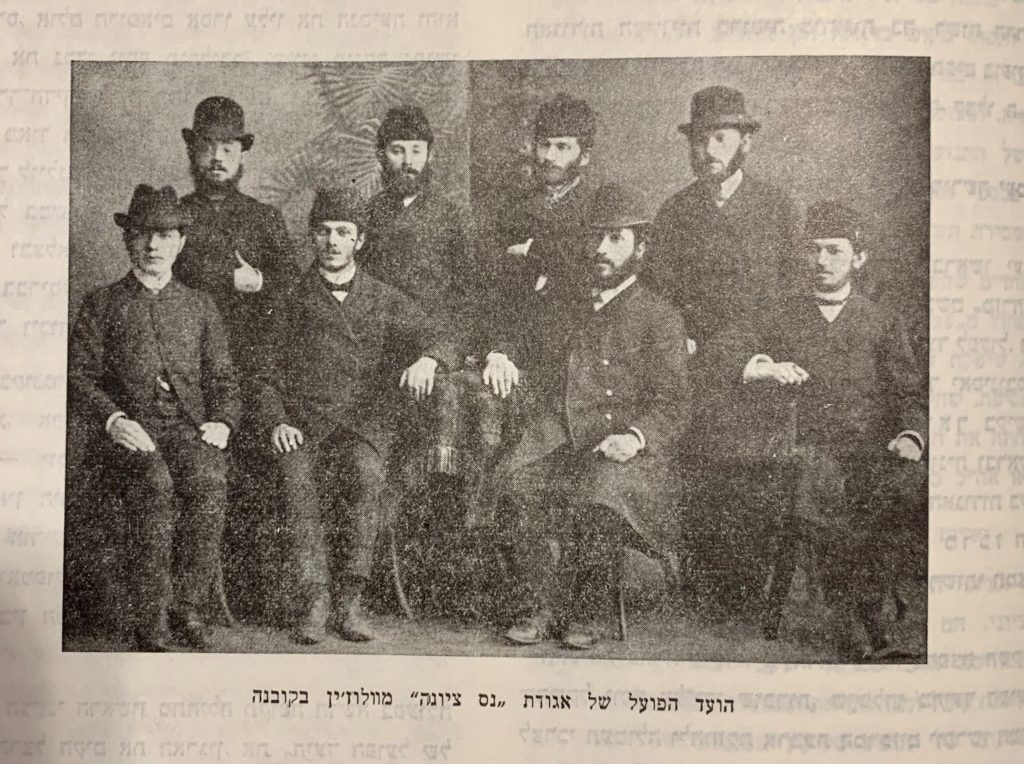

The alternation of Brodsky’s photo is not the only example of such censorship in Besheveli Radin. R. Moshe Mordechai Epstein studied in Volozhin and eventually went on to lead the Yeshivas Kenneset Yisrael in Slabodka. While he was in Volozhin, he was among those who established a proto-Zionist organization, Nes Tsiona. A photograph of the executive members appears in at least three places, yet only in Besheveli Radin is the connection to Nes Tsiona omitted.

In 1960 and 1970, two books published the photo from a copy in Russian Zionist Archives.[20] The 1960s’ version includes a legend that correctly identifies the photo as “the executive committee of the ‘Nes Tsiona’ in Volozhin in 1890.[21] The legend in the 1970 book contains the same language as before, indicating that it is a photograph of the Nes Tsiona executive committee and also identifies each of the men in the picture.[22] Yet, when the same photo appears in Beshvili Radin it is accompanied by an entirely different legend.[23] Instead, Beshvili Radin describes the photograph as depicting “a group of students from Volozhin from those days, R. Moshe Mordechai Epstein who eventually became the rosh yeshiva of Slaboka is sitting second from the right.” The purpose of the group photograph remains a mystery to Beshvili Radin‘s readers.

The history of Volozhin is complex and especially among Haredi writers raised issues that are uncomfortable truths. Some of these authors responded by obscuring or entirely omitting these including the inclusion of secular studies in the curriculum, establishment and membership in non-traditional religious organizations, and the religiosity of some of its students.[24] Beshvilie Radin is but one example. In his introduction, Flato discusses the purpose of Beshvilie Radin describing it as “providing the reader an entirely new perspective of that era.” We can now say that the “new perspective” is one that at times deviates from the historical record.

[1] Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, s.v. “Israel Markovich Brodsky,” (accessed November 20, 2019), https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Бродский,_Израиль_Маркович (Russian).

[2] Id.; Nathan M. Meyer, Kiev: Jewish Metropolis a History, 1859-1914 (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2010), 39.

[3] Meyer, Kiev, 39.

[4] Meyer, Kiev, 39, 40, 71.

[5] For a biography of Reines see Geulah Bat Yehuda, Ish ha-Meorot: Rebi Yizhak Yaakov Reines (Jerusalem: Mossad HaRav Kook, 1985)

[6] Shaul Stampfer, Lithuanian Yeshivas of the Nineteenth Century: Creating a Tradition of Learning, trans. Lindsey Taylor-Guthartz (Oxford, 2015) (original work published 1995 (Hebrew)), 338 (quoting Yitzhak Yaakov Reines, Hotam Tokhnit, vol. 1 (1880), 17n4). For sources regarding the Lida Yeshiva see Eliezer Brodt, “Introduction,” in Mevhar Ketavim m’et R. Moshe Reines ben HaGoan Rebi Yitzhak Yaakov (2018), 12n42. See id. 354-61 for correspondence between the Netziv to R. Yitzhak Yaakov Reines regarding the establishment of a kolel.

[7] Stampfer, Lithuanian Yeshivas, 337-40. One possibility regarding the failure to start the kolel at that time in Volozhin might be attributable to Reines’ recognition that governmental approval was necessary to establish the kolel. Volozhin had a difficult relationship with the Tsarist authorities. See id. at 191-98. Adding a new institution might have been seen as a risk to the operation of the Volozhin yeshiva itself.

[8] Stampfer, Lithuanian Yeshivas, 358-59. Among the conditions of the donation was that during the first year after his death ten men were selected and were required to visit the grave R. Hayim Volozhin’s and leading the prayers, and the recitation of the mourner’s kaddish, in addition to daily study of the mishnayot with the commentary of the Vilna Gaon, and leading the services. The same was done on the yahrzeit of Brodsky’s wife, “ha-Tzkaniyot ha-Meforsemet, Haya.” Dov Eliach, Avi ha-Yeshivot: MaRan Rabbenu Hayim Volozhin (Jerusalem, Machon Moreshet Ashkenaz, 2011) (second revised edition), 600-01. (Thanks to Eliezer Brodt for calling this source to my attention). The manuscript recording the conditions of Brodsky’s gift is currently in the possession of R. Meshulam Dovid Soloveitchik and portions are reproduced by Eliach. See id. 601,634-35.

[9] The Land Bank was created in 1877. Michael H. Hamm, Kiev: A Portrait, 1800-1917 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 10-11. The influence of the Brodskys was such that six members of the family were on the board of an earlier established bank, the Kiev Industrial Bank, (1871). This led some to remark that the bank should be referred to as the “Brodsky Family Bank.” Meyer, Kiev, 40. It is unclear if Israel also sat on the Land Bank board or was just an investor.

[10] Meyer, Kiev, 71.

[11] Meyer, Kiev, 40.

[12] Meyer, Kiev, 171-72. For a discussion of Vilna’s Choral Synagogue and its influence on Vilna’s maskilim see Mordechai Zalkin, “The Synagogue as Social Arena: The Maskilic Synagogue Taharat ha-Kodesh in Vilna,” (Hebrew), in Yashan me-Peni Hadash: Shai le-Emmanuel Etkes, vol. 2, 385-403; see also D. Rabinowitz, “Kol Nidrei, Choirs, and Beethoven: The Eternity of the Jewish Musical Tradition,” Seforimblog, Sept. 18, 2018.

[13] While today, these practices are unremarkable; at that time, there were some who opposed these changes. See generally Moshe Samet, Ha-Hadah Asur min ha-Torah: Perakim be-Toldot ha-Orthodoxiah (Jerusalem: Karmel, 2005). For an earlier discussion of the propriety of choirs and incorporating music in Jewish religious practices see R. Leon Modena, She’lot ve-Teshuvot Ziknei Yehuda, Shlomo Simonson ed. (Jerusalem: Mossad HaRav Kook, 1957, 15-20.

[14] Sergey Yulievich Vitte, Childhood During the Reigns of Alexander II and Alexander III (Russian) at 160.

[15] Dov Eliach, Avi ha-Yeshivot: MaRan Rabbenu Hayim mi-Volozhin (Jerusalem: Machon Moreshet HaYeshivot, 1991), 269. This photograph remains in Eliach’s second and updated version of Avi ha-Yeshivot printed in 2011. See Eliach, Avi ha-Yeshivot: MaRan Rabbenu Hayim me-Volozhin (Jerusalem: Machon HaYeshivot, 2011), 292. Although there are two changes in this version. First, the “well-known philanthropist” becomes a “Rebi” and conveniently the top of the Rebi’s head is cut off so that one can’t tell if the Rebi is wearing a yarmulke.

[16] Menahem Mendel Flato, Besheveli Radin… ([Petach Tikvah]: Machon beSheveli haYeshivos, 2001), 31; Marc Shapiro, Changing the Immutable: How Orthodox Judaism Rewrites Its History (Oxford: Littman Library, 2015), 136. Flato combines both of Eliach’s honorifics into “the philanthropist Rebi Yisrael Brodsky.”

[17] See Dan Rabinowitz, “Yarlmuke: A Historic Coverup?,” Hakirah vol. 4 (2007), 229-38.

[18] For examples see Shapiro, Changing the Immutable.

[19] Another Haredi history of Volozhin published the same year as Beshvili Radin also includes the unaltered photograph. Tanhum Frank, Toledot Beit HaShem be-Volozhin (Jerusalem, 2001), 254.

[20] Yahadut Lita vol. 1 (Tel Aviv: 1960), 507; Eliezer Leone, Volozhin: Sefrah shel ha-Ir ve-shel Yeshivat Ets Hayim (Tel Aviv: Naot, 1970), 121. Despite the attribution to the Russian Jewish Archive there is no other information regarding this archive.

[21] Yahadut Lita, 507. Regarding Nes Tsiona see Stampfer, Lithuanian Yeshivas, 170-72

[22] Leone, Volozhin, 121.

[23] Another Haredi history of Volozhin also uses the same photograph but crops out all but just Epstein. See Frank, Toledot, 256. But in that instance the photo is used as part of a collage of rabbinic figures and explains why the other people are missing.

[24] Stampfer, Lithuanain Yeshivas, 43, 206-07, (secular studies), 167-178 (societies), Abba Bolsher, “Yeshivas Volozhin be-Tukufat Bialik,” in Yeshivas Lita: Perkei Zikronot, eds. Emmanuel Etkes and Shlomo Tikochinski (Jerusalem: Zalman Shazer Center, 2004, Menahem Mendel Zlotkin, “Yeshivas Volozhin be-Tekufat Bialik,” in Etkes, Perkei, 182-92 (histories of Volozhin’s perhaps most well-known black sheep during his time there).

There are two notable works by R. Emden, his Siddur, (

There are two notable works by R. Emden, his Siddur, (