Marc B. Shapiro

One of the most famous examples of haredi censorship relates to R. Zevin. In his classic Ha-Moadim ba-Halakhah, in the section “Ha-Tzomot”, end of ch. 5 (p. 442 in the most recent edition), in discussing if one still needs to do keriah upon seeing the destroyed cities of Judea, R. Zevin writes:

מסתבר, שעם שיחרורן של ערי יהודה משלטון נכרים והקמת מדינת ישראל (אשרינו שזכינו לכך!) בטל דין הקריעה על אותן הערים.

The first thing to notice is that while R. Zevin wrote מסתבר, which must be translated as “it is reasonable”, “it makes sense”, or something similar, Artscroll has turned this into a tentative argument (“it could be argued”). Yet this is not what R. Zevin is saying. “It could be argued” implies that R. Zevin is on the fence on this matter, while מסתבר shows clearly what his view is.[3]

However, the really egregious action of Artscroll comes later in this sentence where Artscroll deletes mention of the establishment of the State of Israel and, most significantly, R. Zevin’s feeling of joy at this event: אשרנו שזכינו לכך!

I have learnt that the men who run Artscroll did not originally know about the censorship just mentioned. They never authorized any distortion of the translation and were surprised to find out what had been done. Yet once learning what had happened, they never took any steps to correct the translation and even defended the alterations. To this day, the matter has not been rectified. It is one thing if in its own works Artscroll tolerates or even encourages distortions, but to take the work of someone else, especially a great Torah scholar, and “correct” it so as to bring it into line with haredi “Daas Torah” is unforgivable. Furthermore, it is a violation of a sacred trust which every translator should be cognizant of. I also wonder if there isn’t a real issue of geneivah involved. If you sell a book supposed to be a translation, and you alter the translation, it is not merely a matter of geneivat da’at but real thievery, since you are selling a product that is not authentic.[4]

Mr. Holder has, for many years, maintained the closest contact with Rav Zevin’s family and has been a prime force in the dissemination of this great Tzaddik’s writings, in both Hebrew and English. It is unthinkable that he would tolerate or engage in any attempt to misrepresent Rav Zevin’s thoughts. . . . According to Mr. Holder, the lines which Mr. Feinholtz quotes were added to the edition published just a few months after the State of Israel was founded, a time when Rabbi Zevin and others still held high hopes for the spiritual impact of the State upon the lives of those Jews living there. As time went on, Rabbi Zevin became disappointed and, in the opinion of the members of his own family, his final Halachic opinion with regard to the law of rending garments on seeing the Judean hills is more accurately reflected in the Artscroll translation than in the version of the passage cited by Mr. Feinholtz.

There is a good deal of falsehood here. To begin with, other than Shemirat Shabbat ke-Hilkhatah, I think Ha-Moadim ba-Halakhah has been reprinted more times than any other modern halakhic text. Neither R. Zevin nor his family ever made any changes to the work. So who are these mysterious family members that Mr. Holder consulted with? R. Nahum Zevin, the one grandson of R. Zevin who is a haredi rabbi, is completely honest in his descriptions of his grandfather’s strong Zionist feelings.[6] R. Nahum tells anyone who asks that the change in the English translation was done without his (or anyone else in the family’s) knowledge or approval. He completely rejects the attempts to distort his grandfather’s legacy, as his grandfather never moved from his Zionist outlook. Thus, in addition to what has already been noted, the distortion of R. Zevin’s words must be seen as a betrayal of the family’s trust. (See also the second to last paragraph of the Hebrew article included in this post.)

More offensive than Artscroll’s distortion of R. Zevin’s halakhic opinion is the omission of his words of thanks for the creation of the State, an omission that goes unmentioned in the letter of Scherman and Zlotowitz. In a typical debating tactic, they offer a response that allows them to pretend that the only issue being discussed is R. Zevin’s halakhic view of rending garments rather than the deletion of his comments about the State of Israel. (Regarding the first matter, does this really have anything to do with Zionism? Is there anyone today, even among the non-Zionist haredim, who rends his garment upon seeing the cities of Judea?[7] Even when it comes to mekom ha-mikdash it seems that for many the practice of keriah has fallen by the wayside, and a number of people have written to justify this. And while I am on the topic, is there any halakhic justification for people not to do keriah when they see places like Bethlehem that have been returned to Arab rule?[8])

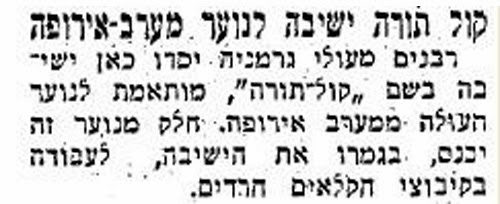

Before going further, let me present a short article in Hebrew written by a friend of mine that also details Artscroll’s fraudulence in this matter.

In Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox, I called attention to two other examples of censorship (omitting Lieberman’s rabbinic title) in Artscroll’s translation of R. Zevin, so it is obvious that the translators felt it was OK for them to take liberties with the text. I know from speaking to people in the haredi world that this sort of thing is very distressing to them. It is no longer surprising when we see censorship and intentional distortions in haredi works. We even expect this and are surprised when a haredi work is actually honest in how it presents historical matters and issues that are subject to ideological disputes. Yet it doesn’t have to be this way. There is no fundamental reason why haredi works can’t express their position without the all-too-common falsehoods. I think the ones most offended by this are those who are part of the haredi world and believe in its ideology, and don’t understand the need to resort to distortions in order to further the truth.

It is noteworthy that R. Henkin saw fit to mention on the tombstone that Hayyim was a student at Yeshiva College (= Yeshivat R. Yitzhak Elhanan).

I would now like to point to an unintentional error in Artscroll’s translation of Ha-Moadim ba-Halakhah. Before last Pesah I took out my copy of The Festivals in Halachah. In reading the chapter on kitniyot, p. 118, I came across the following.

By way of reply, Rav Shmuel Freund, “judge and posek in the city of Prague”

((דין ומו”צ בק”ק פראג published the pamphlet Keren Shmuel, in which he demonstrates at length that no one has the authority to make these prohibited items (kitnios) permissible.

I immediately suspected something wasn’t right, and when I looked at the original I saw that R. Freund was described as דיין מו”ש דק”ק פראג. In translating these words into English, דיין מו”ש became דין ומו”צ (since the English version puts vowels on the Hebrew words דיין became דין), and דק”ק became בק”ק (this latter point is only a minor error).

R. Zevin’s description of R. Freund is put in quotation marks since it is taken from the cover of his Keren Shmuel, as you can observe here.

The translators (who must never have seen the title page of Keren Shmuel) didn’t know what to make of מו”ש and assumed that it was a mistake for מו”צ. They therefore “corrected” R. Zevin’s text. This is one of those cases where a few well-placed inquiries would have solved the translators’ problem. Some of the blame for this error should be laid at the feet of R. Zevin, for he never bothered explaining what מו”ש is and he should have realized that that the typical reader (and translator) wouldn’t have a clue as to its meaning.[9]

מו”ש refers to the highest beit din in Prague, as used in the phrases דיין מו”ש and בית דין מו”ש. But what do the letters מו”ש stand for?[10] This is the subject of an essay by Shaul Kook,[11] and he points out that there has been uncertainty as to the meaning of מו”ש.[12] In fact, R. Solomon Judah Rapoport, who was chief rabbi of Prague and a member of the בית דין מו”ש, was unaware of the meaning.[13] After examining the evidence, Kook concludes that מו”ש stands for מורה שוה. This appears to mean that all the dayanim on the beit din were regarded as having equal standing. The בית דין מו”ש of Prague actually served as an appeals court, something that was found in other cities as well, even going back to Spain.[14] R. Yair Hayyim Bacharach, Havot Yair, no. 124, refers to one of the dayanim on this beit din as אפילאנט, and the new edition of Havot Yair helpfully points out that the meaning of this is דיין לערעורים.[15]

Some people have the notion that the appeals court of the Israeli Chief Rabbinate is a completely new concept, first established during the time of R. Kook. This is a false assumption.[16] (The Chief Rabbinate’s בית דין לערעורים is also known as בית דין הגדול).

R. Moshe Taub has called my attention to another error in the translation of Ha-Moadim ba-Halakhah. In discussing what should be done first, Havdalah or lighting the menorah, R. Zevin writes (p. 204):

ברוב המקומות נתקבל המנהג שבבית מבדילים קודם, ובבית הכנסת מדליקים קודם

The translation, p. 89, has this sentence completely backwards: “Most communities have adopted the following custom: at home – Chanukah lights are lit first; in the synagogue – Havdalah first.”

Since we are on the issue of errors in Artscroll, here is another one which was called to my attention by Prof. Daniel Lasker. In the commentary to Numbers 25:1, Artscroll states:

After Balaam’s utter failure to curse Israel, he had one last hope. Knowing that sexual morality is a foundation of Jewish holiness and that God does not tolerate immorality – the only time the Torah speaks of God’s anger as אף, wrath, is when it is provoked by immorality (Moreh Nevuchim 1:36) – Balaam counseled Balak to entice Jewish men to debauchery.

Yet Rambam does not say what Artscroll attributes to him. Here is what appears in Guide 1:36:

Know that if you consider the whole of the Torah and all the books of the prophets, you will find that the expressions “wrath” [חרון אף], “anger” [כעס], and “jealousy” [קנאה], are exclusively used with reference to idolatry.

The Rambam says that the language of “wrath” is only used with reference to idolatry, but somehow in Artscroll idolatry became (sexual) immorality. This text of the Moreh Nevukhim is actually quite a famous and difficult one, and the commentators discuss how Maimonides could say that ויחר אף is only used with reference to idolatry when the Torah clearly provides examples of the words in other contexts. In his commentary, ad loc, R. Kafih throws up his hands and admits that he has no solution.

ושכאני לעצמי כל התירוצים לא מצאו מסלות בלבבי, והקושיא היא כל כך פשוטה עד שלא יתכן שהיא קושיא, אלא שאיני יודע היאך אינה קושיא

Returning to the issue of

kitniyot, in a

previous post I raised the question as to why, according to R. Ovadiah Yosef, all Sephardim and Yemenites who live in Israel are to follow the practices of the

Shulhan Arukh but he doesn’t insist on this when it comes to Ashkenazim. If R. Joseph Karo is the

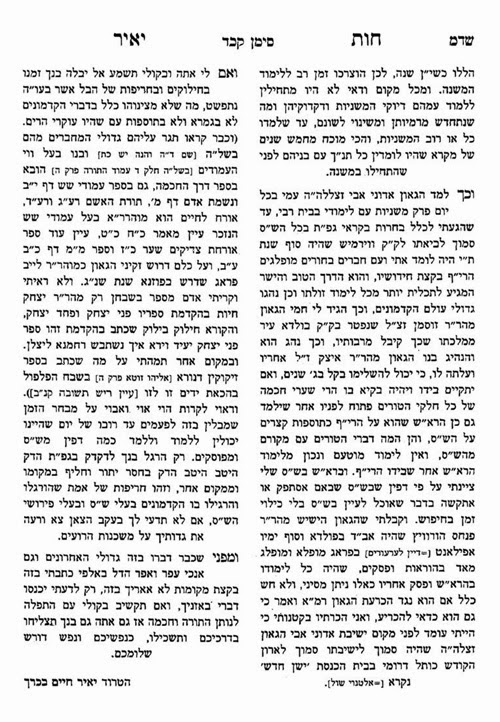

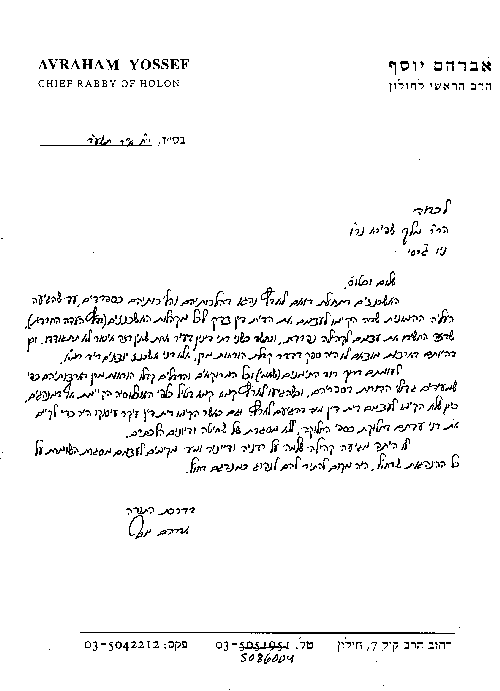

mara de-atra, shouldn’t this apply to Ashkenazim as well?[17] I once again wrote to R. Avraham Yosef and R. Yitzhak Yosef seeking clarification. Here is R. Avraham’s letter.

Unfortunately, his history is incorrect. To begin with, it is not true that all of the Ashkenazim who came on aliyah before the “mass aliyah” (which apparently refers to the late nineteenth century) adopted the practices of the Sephardim.[18] It is also not true that the beit din established by the Ashkenazim in the nineteenth century is the beit din of the Edah Haredit. The Edah Haredit is a twentieth-century phenomenon. The historical successor of the beit din of R. Shmuel Salant was the Jerusalem beit din of which R. Kook was av beit din, as he was the rav of Jerusalem (and R. Zvi Pesah Frank served on the batei din of both R. Salant and R. Kook). The Edah Haredit beit din was a completely new creation. As for the Yemenites, Moroccans, and Iraqis, when the great immigration of these groups occurred, many thousands came on aliyah together, (i.e., as complete communities) and thus they never saw themselves as required to reject their practices in favor of the Shulhan Arukh. The fact that they didn’t establish special batei din is irrelevant. In fact, R. Avraham’s last paragraph is a good description of how these communities arrived in the Land of Israel, and is precisely the reason why their rabbinic leaders almost uniformly rejected R. Ovadiah Yosef’s demand that they adopt the Shulhan Arukh in all particulars.

Here is R. Yitzhak Yosef’s letter to me, which has a different perspective.

He cites R. Joseph Karo’s responsum, Avkat Rokhel, no. 212, which requires newcomers to adopt the practices of the community to which they are going even if they come as large groups. He then says that Ashkenazim never adopted this viewpoint, but instead held to the opinion of R. Meir Eisenstadt (Panim Meirot, vol. 2, no. 133). According to R. Eisenstadt, only individuals who come to a town must adopt the local practice, but not if they come as a group and establish their own community.[19]

Let me now complicate matters further. If you recall, in the earlier post I discussed how R. Ovadiah Yosef’s writings assume that Ashkenazim have to abstain from kitniyot on Pesah. I raised the question if an Ashkenazi could “become Sephardi” and thus start eating kitniyot (and also follow Sephardic practices in all other areas). R. Avraham Yosef wrote to me that this is permissible while R. Yitzhak Yosef wrote that it is not.

R. Yissachar Hoffman called my attention to the fact that in the recent Ma’yan Omer, vol. 11, p. 8, R. Ovadiah was himself asked the following question:

אשכנזי שרוצה לנהוג כמו הספרדים במנהגים ולדוגמא לאכול קטניות בפסח, אך רוצה להמשיך ולהתפלל כנוסח אשכנז. האם הדבר אפשרי.

R. Ovadiah replied:

יכול רק בקטניות, אך עדיף שבכל ינהג כמרן

What R. Ovadiah is saying (and see also the editor’s note, ad loc., for other examples) is that R. Avraham’s answer is correct, namely, that an Ashkenazi can “become Sephardi” (and eat kitniyot). It is significant that R. Ovadiah allows such a person to continue praying according to Ashkenazic practice. Here are the pages.

2. On my recent tour of Italy I spent a good deal of time speaking about the great sages of Venice and Padua. One such figure was R. Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen (1521-1597), known as מהרשי”ק, the son of the famous R. Meir Katzenellenbogen, known as Maharam Padua. While R. Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen is basically forgotten today, he was the most important Venetian rabbi in his day. He was also the father of Saul Wahl, who became famous in Jewish legend as Poland’s “king for a day.”[20]

In 1594, R. Katzenellenbogen’s collection of derashot, entitled Shneim Asar Derashot, appeared. Here is the title page.

When the volume was reprinted in Lemberg in 1798, the publisher made an error and on the title page attributed the volume to מהר”י מינץ , the son of Maharam Padua.

Apart from not knowing who the author of the volume was, the publisher also didn’t realize that R. Judah Mintz (died 1508[21]) was the grandfather of Maharam Padua’s wife, meaning that he was the great-grandfather of R. Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen.

When the volume was reprinted in Warsaw in 1876 the publisher recognized the problem but confounded matters.

Rather than simply correcting the mistake from the 1798 title page by attributing the volume to R. Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen, he kept the information from the mistaken title page but tells the reader that מהר”י מינץ is none other than “R. Samuel Judah Mintz”, a previously unheard of name.

The most recent printing has gets it even worse.

Now the original title of the book, שנים עשר דרשות, is simply omitted, and the book is called דרשות מהר”י מינץ

The authentic R. Judah Mintz of Padua is known for his volume of responsa that was published in Venice in 1553, together with the responsa of R. Meir Katzenellenbogen. Here is the title page.

R Judah Mintz’s responsa were reprinted in Munkacs in 1898 together with a lengthy commentary by R. Johanan Preshil.

The book was also reprinted in 1995, edited by R. Asher Siev.

Unfortunately, Siev was unaware of the 1898 edition. He also makes the mistake (see p. 353) of stating that R. Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen was referred to as מהר”י מינץ because his mother’s family name was Mintz. I have seen no evidence that he was ever referred to as such in his lifetime or in the years after, and as mentioned, this was simply a printer’s mistake. I consulted with Professor Reuven Bonfil and he too is unaware of any reference to Katzenellenbogen being referred to as מהר”י מינץ, which supports my assumption that this all goes back to the mistaken title page.[22]

3. In my last post I mentioned how in years past there were shiurim combining students from Merkaz and Chevron and also Merkaz and Kol Torah. This is obviously unimaginable today. For another example showing how Yeshivat Kol Torah has changed, look at this picture, which appears in Yosef and Ruth Eliyahu, Ha-Torah ha-Mesamahat (Beit El, 1998), p. 105.

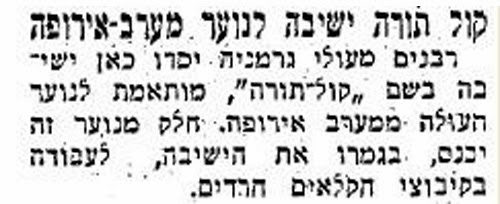

I guarantee you that even on the hottest of days, none of the Kol Torah students will be wearing shorts. For those who don’t know, Kol Torah was founded by German Orthodox rabbis and was originally very different than it is today. Here is how it was described upon its founding, in a short notice in Davar, August 27, 1939.

It is hard to imagine today, but this was a yeshiva that actually intended for some of its students to take up agriculture. See also

here which cites R. Hayyim Eliezer Bichovski, Kitvei ha-Rav Hayyim Eliezer Bichovski (Brookyn, 1990), p. 180, that the Chafetz Chaim said that yeshiva students in Eretz Yisrael should learn nine months a year and work the land the other three months

Speaking of shorts, here are a couple of pictures showing how the boys of the German Orthodox separatist Adass Jisroel community looked when playing sports (also notice the lack of kippot).

This was the community of R. Esriel Hildesheimer and R. David Zvi Hoffmann. The pictures come from Mario Offenburg, ed., Adass Jisroel die Juedische Gemeinde in Berlin (1869-1942): Vernichtet und Vergessen (Berlin, 1986).

Here is how the girls dressed for sports, also with shorts and sleeveless.

And here is how the boys and girls looked when not at a sporting event.

These pictures come from Max Sinasohn, ed., Adass Jisroel Berlin (Jerusalem, 1966).[23]

4. Some people didn’t appreciate the humor in

my post with regard to the Gaon R. Mizrach-Etz. I think they should lighten up, and in a previous post, available

here, I gave some references to humor in rabbinic literature. This was followed up by a more extensive post by Ezra Brand, available

here.

According to the commentary Siftei Hakhamim, it is not just the talmudic sages who would at times show their humorous side, but on at least one occasion Moses thought that God himself was joking with him!

In Ex. 33:13 Moses says to God: ועתה אם נא מצאתי חן בעיניך. Rashi explains this to mean: “If it is true that I have found favor in Your eyes.” This means that Moses was in some doubt as to whether he found favor in God’s eyes, but this is problematic since in the previous verse Moses quotes God as saying to him, “you have also found favor in My eyes.” So if God told Moses that he found favor in His eyes, how can Moses be in doubt and say to God, “If I have found favor in Your eyes”?

Here is the Siftei Hakhamim.

According to Siftei Hakhamim, Moses was in doubt if he really found favor in God’s eyes, since even though God said he did, perhaps God was joking just like people joke around!

דלמא מה שאמרת מצאת חן בעיני מצחק היית בי כדרך בני אדם

5. I want to call readers’ attention to a recent book, Shevilei Nissan, which is a collection of previously published essays from R. Nissan Waxman. There is lots of interesting material in the book, and let me mention just a few things.

In Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters, p. 75 n. 302, I referred to R. Yaakov Avigdor’s strong criticism of R. Hayyim Soloveitchik’s approach. R. Avigdor also criticized R. Solomon Polachek, the Meitchiter. R. Waxman was a student of the Meitchiter, and on p. 23 n. 1, he comes to his teacher’s defense.

On p. 150, R. Waxman, who was the rav of Lakewood, mentions the problem of how some yeshiva students are halakhically more stringent than their teachers. He quotes R. Yaakov Kamenetsky in the name of R. Aharon Kotler how a student once visited R. Kotler and when the latter offered the student some cookies, the student was reluctant to take before asking which bakery they came from. (Perhaps this behavior can be explained by what I have heard – and maybe someone can confirm this – that in R. Aharon Kotler’s day the Lakewood bakery Gelbstein was not under hashgachah, and yet R. Kotler bought his challot from it. See also

here and

here The original post referred to in these links has definitely been taken down.)

On p. 233, R. Waxman notes that even though we have the principle, “A Jew who sins remains a Jew”, in actuality, it is possible for a Jew to so remove himself from the Jewish people (e.g., apostasy) that as far as most things are concerned, he is indeed no longer regarded as Jewish. This essay was written concerning the “Brother Daniel” case, and R. Waxman’s approach is similar to that of R. Aharon Lichtenstein who also wrote a famous article on the topic, “Brother Daniel and the Jewish Fraternity,” republished in Leaves of Faith, vol. 2, ch. 3.

On pp. 251ff., R. Waxman deals with Menahem Mendel Lefin’s Heshbon ha-Nefesh, an influential mussar text which as many know was influenced by a work of Benjamin Franklin.

6. I want to also call readers’ attention to two other books recently sent to me. The first is R. David Brofsky, Hilkhot Moadim: Understanding the Laws of the Festivals. This is very large book (over 700 pages) dealing with the Holidays and is a welcome addition to the growing number of non-haredi halakhah works in English.. In a future post I hope to deal with it in greater depth. The second book is Haym Soloveitchik, Collected Essays, vol. 1, published by Littman Library, my favorite publisher. This book is required reading for anyone with an interest in the history of medieval halakhah. I was happy to see that it also includes two essays that appear here for the first time. Furthermore, Soloveitchik’s classic essay on pawnbroking (which was his first significant article) has been expanded to almost double the size of the original. In the new preface to the essay, he writes: “Every essay is written for an imagined audience, and mine was intended for the eyes of Jacob Katz, Saul Lieberman, and my father.”