A Third Way: Iyyun Tunisai as a Traditional Critical Method of Talmud Study[1]

by Joseph Ringel

The following is an excerpt from an article with the above title by Joseph Ringel. The full article, including the footnotes detailing the source materials, and the appendix, have been published in the Fall 2013 issue of Tradition (46:3), and is available for purchase at http://www.traditiononline.org/.

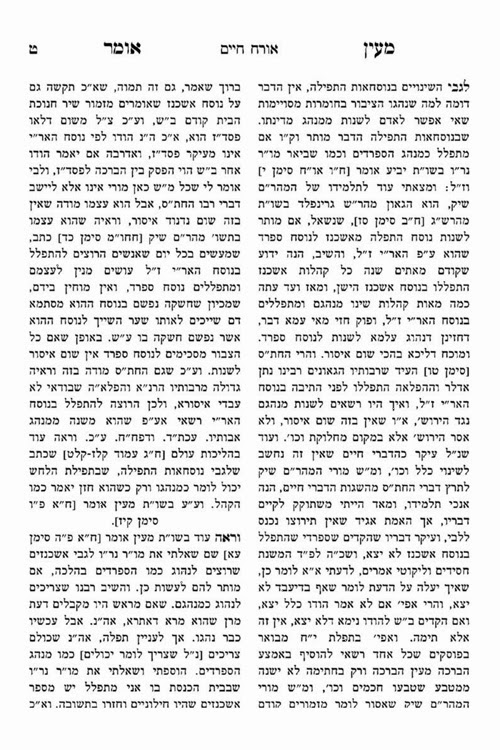

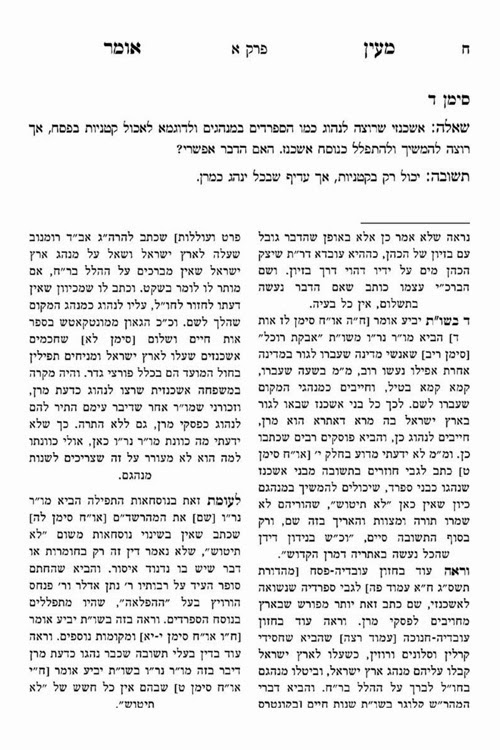

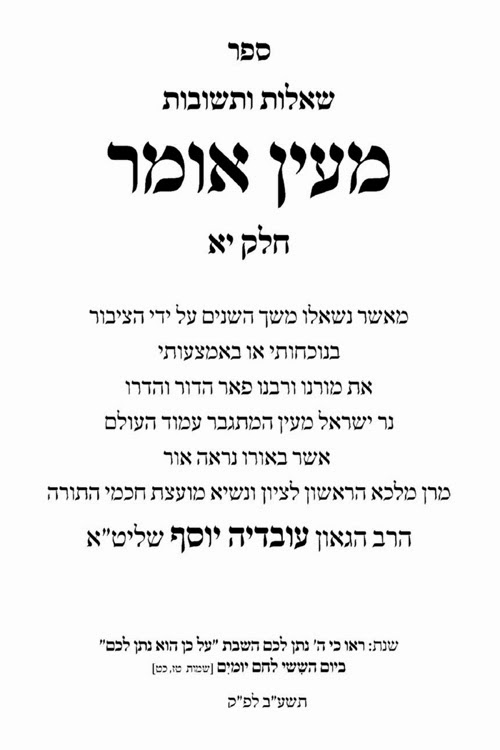

In recent years, scholars have taken a renewed interest in elucidating the specific methods used to study Jewish texts in yeshivas, both past and present. For example, Daniel Boyarin elucidated the classical late medieval/early modern Sephardic approach to Talmud study, and Norman Solomon published his dissertation on the development of the Analytic/Conceptual/“Brisker” approach to Talmud study in Lithuania in book form. These works are historical monographs, the purpose of which is to relate to the development of specific methods at specific times in history, not to connect those methods to the approaches utilized in present-day yeshivas. More recently, Mordechai Breuer wrote a magnificent work detailing the curricula and educational methods used in yeshivas throughout the ages until the present. Yet, despite Breuer’s painstaking research, he misses some of the more recent incarnations of older methodologies that he himself mentions. In 2006, Yeshiva University published the proceedings of the 1999 Orthodox Forum, which dealt with issues surrounding contemporary lomdut, in a volume entitled Lomdut: The Conceptual Approach to Jewish Learning. As can be seen from the title, the volume conflates contemporary lomdut (a term that is hard to define with precision but which will be used to describe any form of in-depth study of a text) with the Conceptual/Analytic /Brisker Approach and does not deal extensively with other specific forms of lomdut. In some cases, alternatives to the Brisker approach are presented as either halakha-oriented methods uninterested in more theoretical discussions or as academic approaches that are hostile to Jewish tradition.

This article will present the basics of one alternative method of lomdut, which is dubbed by its main contemporary champion, R. Meir Mazuz, as “Iyyun Tunisai,” or “Tunisian Analysis.” The first section of the article will present the basics of Iyyun Tunisai and its origins in Jewish tradition, thereby showing that not only is it a viable alternative to the Brisker approach but it is a fully traditional method with roots in classic rabbinic sources. The second section presents R. Mazuz’s critiques of alternative methods of study, in which he claims that the critical approach utilized by the Tunisian method allows the analyst to reach the correct understanding of the text at hand and to appreciate why each element of the text is an integral part of that text. Thus, unlike academic methodologies, which often undermine the sugya (the Talmudic discussion), Iyyun Tunisai uses a critical approach in order to explain and link the different terms of the sugya, thereby strengthening the integrity of the sugya. The third section concludes with an analysis of the place of Iyyun Tunisai in the yeshiva world and its prospects for the future.

I. Jerba in Bnei Brak: Yeshivat Kisse Rahamim and the Renewal of Sephardic Iyyun

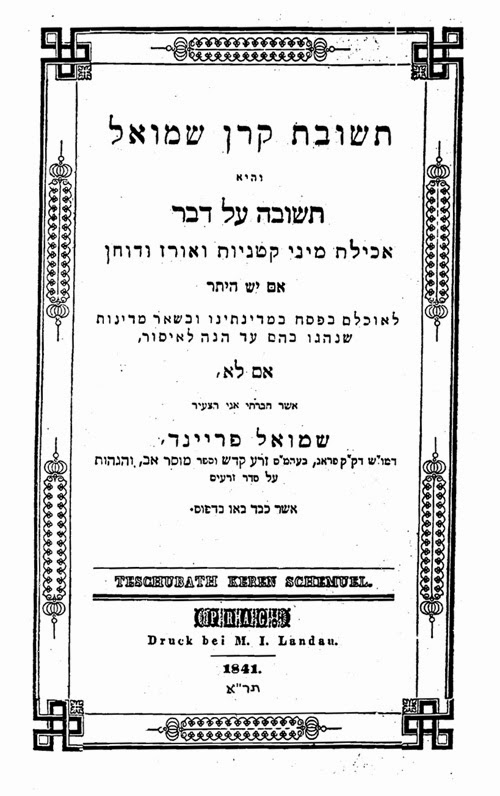

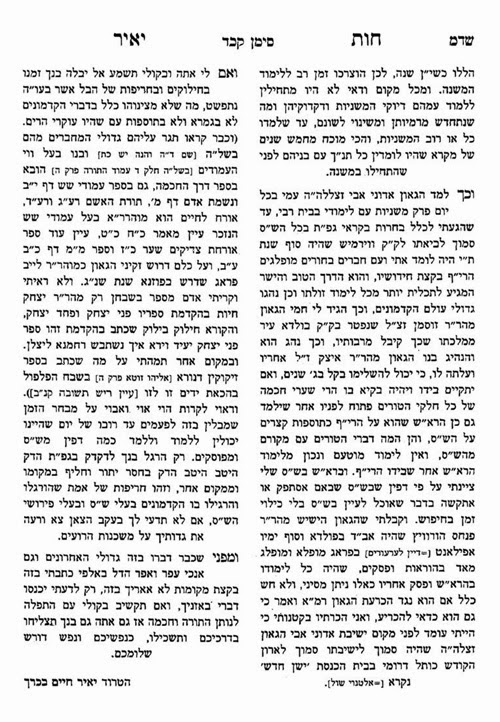

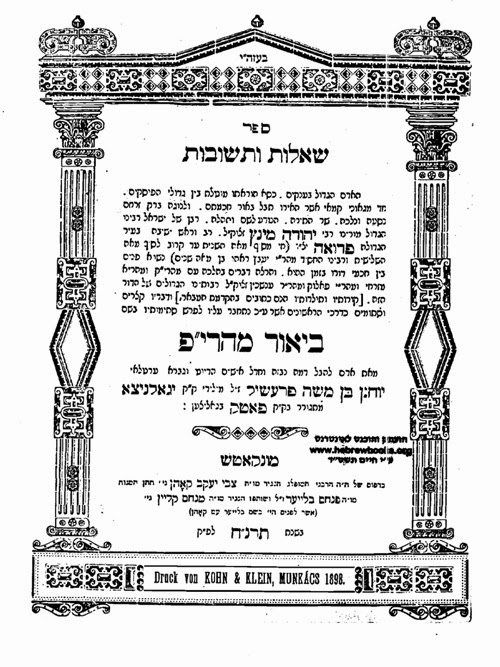

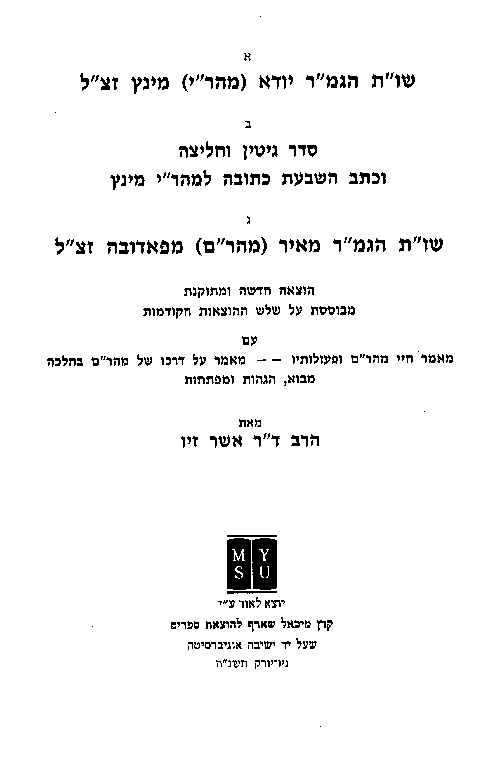

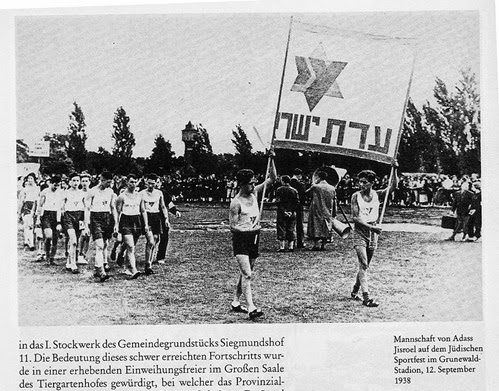

As noted above, one of the main competitors for intellectual dominance in the yeshiva world is Iyyun Tunisai, a Sephardic method of study whose roots go back hundreds of years. Rabbi Meir Mazuz of Yeshivat Kisse Rahamim in Bnei Brak is the one responsible for the revival of this method. In order to gain a full appreciation for the context in which this method is being revived, it is necessary to give a brief overview of Yeshivat Kisse Rahamim. The yeshiva was founded by R. Meir Mazuz’s father, Rabbi and Tunisian Supreme Court Justice Matsliah Mazuz in Tunisia in 1962/63, and then re-established by his sons (Rabbis Meir and Tsemah Mazuz) in Israel in 1971, after having fled their native Jerba (an island off the Tunisian coast whose Jewish community was renowned for its scholarship) following the murder of their father by an Arab nationalist. Their school is an elite yeshiva with a rigorous examination process (only twenty-five percent of applicants are accepted), and its methodology is in keeping with its desire to produce not merely scholars but the leading posekim (jurists) of the next generation. The yeshiva also houses a bookstore that carries books published by Mekhon ha-Rav Matsliah, a press named for R. Matsliah Mazuz that (re-) publishes old Jerban and Tunisian commentaries on Talmud, grammatical works, new commentaries and textbooks written by students, graduates, and rabbis of the yeshiva, as well as siddurim and tikkunim based on the Jerban custom.

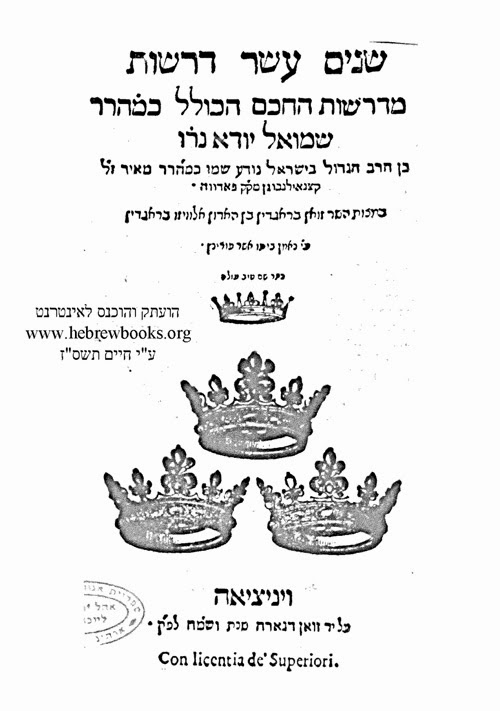

It is in this context of Sephardic-Jerban-Tunisian religious revival that the renewal of this method of iyyun is taking place. In two essays that he wrote on the subject of method of study (derekh limmud), R. Meir Mazuz (henceforth “R. Mazuz”) insists that, though he terms the method he champions “Tunisian analysis,” he assures his readers that the method was not limited to that geographical area but was at one point used throughout the Jewish world. Indeed, Iyyun Tunisai was originally codified not by a Tunisian rabbi, but by the Castilian R. Yitshak Canpanton (or Campanton; 1360-1463) in his Darkhei ha-Talmud (“The Ways of the Talmud”). Sephardic Iyyun as it was originally

practiced was the subject of a seminal study by Daniel Boyarin, who claims that R. Canpanton interpreted various methods of analysis used in the Talmud in light of theories of semantics and language that were current in medieval Scholastic-Aristotelian works. Boyarin remarks that the method spread following the expulsion of the Jews from Spain to the sixteenth and seventeenth-century academies of “Safed and Jerusalem… Constantinople and Salonika… Cairo and Fez,” and then exclaims, “and how surprising it is that this method of learning has been almost entirely forgotten and is barely mentioned in the research laboratory (sadnat ha-mehkar) and in the house of study (beit ha-midrash) up until our very generation.” This carefully worded statement shows that the method has nevertheless not been entirely forgotten, even as the author does not seem to be aware of its existence in any significant beit midrash. This section will show that Sephardic iyyun has in fact been preserved in the “houses of study” of North Africa and is now undergoing a revival in Israel. Because Ashkenazi methods have dominated the yeshiva system for so long, a successful revival must encompass two elements: 1) a re-codification of the fine points of the methodology, with which most yeshiva-educated rabbis would not be familiar, and 2) a well-articulated attack on the regnant

Ashkenazi methods that threaten the revival. R. Mazuz’s writings do both. What follows is an analysis of R. Mazuz’s positions as expressed in his first essay on methods of study, aptly entitled “Ma’amar be-Darkhei ha-Iyyun” (“Article on Methods of Analysis”).

The Basic Assumptions of the Method

R. Mazuz introduces his first article by terming his analytical approach ha-iyyun ha-yashar, “the straight analysis,” a term that functions as a polemical tool against other methods that he feels muddle the text instead of elucidating it in a step-by-step process. In vouching for the approach of ha-iyyun ha-yashar, R. Mazuz quibbles with Ramban’s theory of law, which asserts that, while scientific discussions result in exact conclusions, Jewish legal argumentation does not allow for definitive proofs. In contrast, R. Mazuz contends that over the centuries a methodology developed with the type of exactness necessary to properly determine the law. R. Mazuz’s rejection of inexactness in law parallels the same rejection that, according to Daniel Boyarin, stood at the heart of R. Canpanton’s methodology and its Aristotelian assumptions, which viewed any idea or interpretation of a text as provable or disprovable based on rational analysis. R. Mazuz’s confidence in the scientific acumen of his method becomes explicit when he states that the method’s goal is to “dig into and penetrate the original intention of the statements [at hand] with full confidence, without any hesitation or doubt.”

After a discussion of his method’s roots in the rabbinic tradition, R. Mazuz goes on to describe the method in depth:

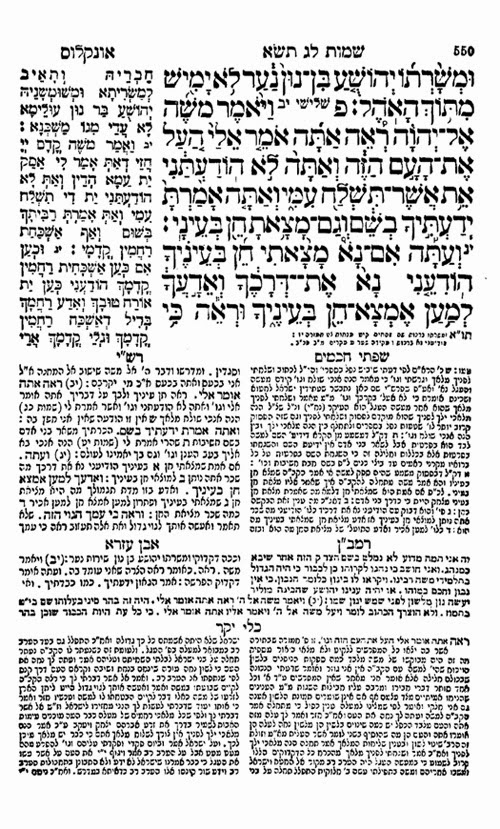

The foundation of the foundations of iyyun is that there is nothing missing [from] or added onto the language of the Gemara, Rashi, and Tosafot. There is nothing missing – because the text has not come to shut out [information] but to explain [matters], and it is not proper [to think] that the main elements of the matters [under consideration] are missing from the Talmudic discussion [Aramaic sugya] and its commentaries, for they [the rabbis] have not come to test us with riddles… And there is nothing added – because our rabbis have always tried to write with brevity and exactness, [with] the small carrying the abundant [i.e. with a small number of words carrying great depth].

What R. Mazuz considers to be the foundation of Iyyun Tunisai is in fact already elucidated by R. Canpanton. Elements of one passage of R. Canpanton are echoed in R. Mazuz’s description above:

And always attempt to impute necessity for all of the words of a commentator or an author in all of his language: why did he say it

and what did he intend with that language, whether to explain [an issue] or to derive [a concept] from another explanation or to resolve a difficulty or a problem. And take heed to limit [le-tsamtsem] his language and to derive [concepts from] it in a way that there will not be an extra word, for if it were possible express his intent, for example, in three words, why did he express [himself using] four [words]? And so you should do with the language of the Mishna and Gemara, that is, you should check their language so that there not be an extra word, and when it appears to you to be extra go back and analyze well, for they did not expand their words unnecessarily, for it is not a small matter, and the splendor of sages is to minimize words so that many concepts are included in small [numbers of] words, and to make their words few in quantity but great [lit. “many”] in quality, and there should not be within their words an extra word, even [if it consists] of one letter, as they [the Sages] have said ([B.T.] Hullin 63b), “A person should always teach his students in a concise way,” as you see in our Holy Torah, which was given from the Mouth of the Mighty One, which speaks with a concise language but includes many things…

The Importance of Syntax

R. Mazuz identifies the importance of syntax as the second major element of Iyyun Tunisai. He criticizes those who downplay the importance of understanding each word and its implications and the proper stopping points of statements, and complains that many students do not know the meanings of basic expressions, which can change depending on context. R. Mazuz then offers an example that highlights the importance of paying attention to syntax. In this example, an erroneous interpretation of a statement could have easily been averted if the commentator had thought about where to properly end the sentence.

R. Mazuz’s focus on the meaning of words is not paralleled in R. Canpanton’s codification, possibly because it is so simple that no reiteration is needed. However, in the current educational climate, R. Mazuz feels that stating what should be obvious is necessary. It seems that the tendency in many yeshivas to emphasize advanced analysis contributes to the lack of focus on more simple syntax. R. Mazuz feels that this lack of focus on the basics leads to avoidable misinterpretations of the text.

Commentary for the Purpose of Preventing Alternative Mistaken Interpretations

R. Mazuz proceeds to describe the third major element of Iyyun: “The third general rule of the methods of Iyyun is to ask, in every place, what was Rashi, Tosafot, or Maharsha bothered by, and from which error they were protected from that word and that sentence…”” In other words, the analyst studying the text should ask himself why a classical commentary would add in a seemingly extra word, or would use a seemingly odd phrase. Most often, the answer is that the commentator in question wanted to prevent his readers from making a mistaken assumption about the subject at hand, which they would have made without the quixotic phraseology that the commentator used. It follows that the seemingly extra word or the seemingly awkward phrase is in fact neither extra nor awkward, but necessary for the correct understanding of the text under discussion.

This type of linguistic analysis assumes that the unusual language of a commentator is used to prevent the reader from coming to an incorrect conclusion. This conclusion is referred to by the classic Sephardic me’ayyenim as sevara mi-baHuts, lit. “the logical construction from the outside” – i.e., a thought process whose origin comes from outside the text. R. Canpanton writes as follows:

… And afterwards [i.e. after reading through the text a number of times and determining what is stated explicitly and what should be

understood implicitly] return to analyze if there is a novelty in what is understood from the language or not… if there is no novelty, raise a difficulty with the one who makes such a statement… “What is it [i.e. the statement] teaching us? [It is] obvious!” And if there is a novelty in its inference [i.e. if there is a novelty in what you have inferred from the statement], but there is no novelty in the essence of the statement [i.e. in the plain meaning of the statement], it is possible to say that he [i.e. the speaker] chose it [i.e. chose to make the statement in the way that he did] because of the inference… And certainly look carefully at every statement [and ask] what you would have thought based on your logic or what you would have adjudicated based on your sense before the tanna or amora would have come [to make his statement], for a great benefit will result for you from this [method], for if you yourself would have thought as he [did], ask him, “What [does this statement] teach us? It is obvious!” And if your logic contradicts his, you should know and search out what the necessity was that caused him to say thus, and [find out] what the weakness or bad element was within what you yourself had thought, and this [i.e. the logic you would have originally assumed] is called “the logical construction from the outside.”

Due to the abstract nature of this section, it is highly recommended that readers look through the appendix, which offers a concrete example of sevara mi-baHuts.

The Logical Flow of the Text

R. Mazuz identifies a fourth element of ‘Iyyun Tunisai, which relates to the logical flow of the text of Tosafot, who are known for posing many questions and answers in a row. R. Mazuz suggests stopping after each question-and-answer pair to analyze how each question was

answered and how the next question relates to the previous question-and-answer. In this way, the student can identify in what way the main issue being discussed is resolved. This resolution is known as “the center of the resolution,” or merkaz ha-teruts.

The assumption that every element in a rabbinic text relates to the previous one or next one is spelled out explicitly by R. Canpanton at the beginning of Chapter Ten of his Darkhei ha-Talmud: “Always, for every statement and for every concept that is situated next to another, whether in Talmud or in Scripture (ba-Katuv), carefully observe the relationship and connection between those concepts situated next to each other, including what order the speaker is leading (molikh) with his words.”

R. Canpanton’s statement was made in reference to the literary structure of all rabbinic texts and specifically the Talmud. R. Mazuz’s focus on the literary structure of Tosafot is a natural outgrowth of Sephardic Iyyun’s general concern with the flow of the text. The emphasis on Tosafot began, at the very earliest, during the generation after the expulsion from Spain, with the spread of printed editions of the Talmud that included Tosafot’s commentaries. R. Canpanton himself never mentions Tosafot in his work, probably because manuscripts of Tosafot’s writings did not have widespread circulation in Spain. Instead, other passages highlight the importance of carefully analyzing Rashi and Ramban, whose commentaries were available at the time.

The Role of Writing and Revision

The fifth and final major element of Iyyun Tunisai that R. Mazuz identifies is the importance of writing and revision following one’s studies. The student should summarize his understanding of the commentary or Tosafot he is studying as a test to see whether he has understood it properly. If the student’s own words seem to match the commentator’s but are simply more expansive, the student has understood; if not, the student should review the commentary and revise his statement. Aside from the clarity of understanding the student gains, frequent writing and revision allows the student to express his ideas clearly. R. Mazuz notes that the rabbis of Jerba traditionally educated their students in such a manner, training their students to write their own novellae in a clear and organized fashion.

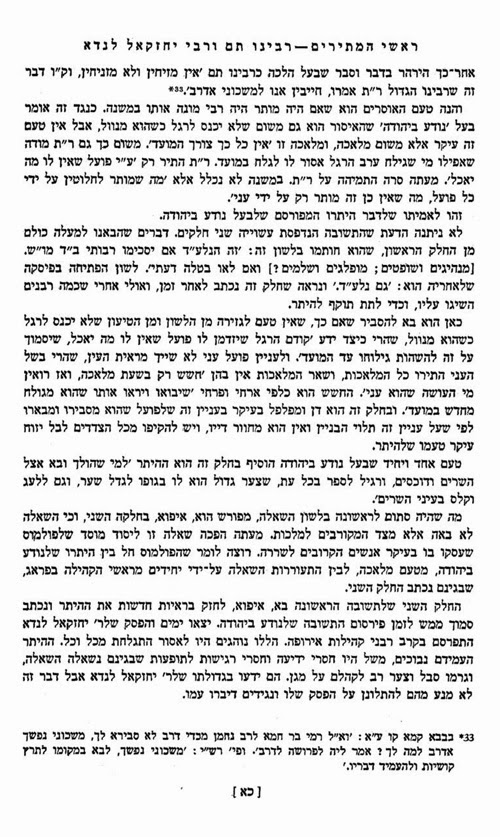

R. Mazuz’s Polemic against Lithuanian-style Methodologies and Its Significance

After having stated earlier in his essay that there is nothing extraneous to, or missing from, the language of the classical Jewish texts, R. Mazuz launches into a justification of this assumption and a polemic against alternative methods of study:

It follows that, if a person overloads explanations and commentaries regarding the intent of the early commentaries that do not flow necessarily (be-hekhreah) from the implication of the language and [of] the style or from the force of a contradiction… we should not accept his commentaries, but [instead] we should ask him, “What forced you [to say] thus? If you would like to dress [i.e., add on layers of meaning to the subject] and to expound [on it], expound and receive reward [for your efforts to come up with original ideas], but to say that Rashi or Rambam or one of the early commentaries intended abstract ideas and definitions that are ‘the finest of fine to the point where they cannot be examined’[2] – from where did this [conclusion] come to you? According to your words [i.e. explanation], why didn’t they [the early commentators] write [what you have expounded] explicitly? Do they speak in secret? Were they, God forbid, challenged [in their ability] to express [themselves] in writing, or did the matter in their eyes [have the status of] ‘the Mystery of Creation and the ‘Mystery of the Chariot,’ until hundreds of years later others arose to explain [their ideas] to them?” – From here derives the expression which is common among us [i.e. the Tunisian Jews], “rather, it is necessary” (ella mukhrah). And it is almost impossible to go through a single discussion in Iyyun Tunisai without [encountering the expression] “rather, it is necessary” tens of times… And in truth, through the necessity, the one who studies arrives at a straight and clear understanding, without dark cracks or crevices [an expression equivalent to “without any ambiguity”]. Everything is clear and lucid. If an objection is

found from elsewhere [i.e. a different source not under discussion], let it remain an objection, as “a person does not die from an [unanswered] objection.” And this is the strength of iyyun: one who learns according to the method of pilpul and of the innovation of and breaking of logical constructions (sevarot) [that derive] from the air [i.e. one who resolves difficulties by advocating ungrounded logical constructions] will many times come across a specific discussion or source that uproots his entire pilpul, and because of his concern for his work, he will [come up with]… different forced explanations and will bend what is upright… But [for] one who learns in depth (ha-me’ayyen), this is not so. If he finds a possibility to iron out difficulties and to resolve contradictions, he is praiseworthy, but if he does not find [a solution], he does not retreat from his iyyun because of this, but says, “this is the [proper] understanding of the matters [at hand], and one should not veer off from the simple explanation (peshat).” Our rabbis the Tosafists, who resolved contradictions between hundreds of Talmudic discussions and [thereby] “made the entire Talmud into the likeness of a sphere”… were not ashamed to admit that there are no fewer than thirteen contradictory Talmudic discussions that are impossible to resolve… but that, nevertheless, the simple explanation should not be stripped [of its plain meaning], and what is concrete [i.e. obvious] should not be denied.

As a whole, R. Mazuz’s description is much less technical than that of R. Canpanton, thereby showing that it is intended for a different type of audience. This wide audience is the system of yeshiva students and the general community that draws from it, most of whom are studying according to the methods of pilpul mentioned by R. Mazuz. For this reason, R. Mazuz’s description of the method is polemical – he attacks alternatives to Iyyun Tunisai because he feels they project their own ideas onto the statements of earlier commentaries. R. Canpanton’s description is very technical and, in other passages, makes use of contemporaneous philosophical terminology. His style is descriptive in nature and seems to be merely codifying the specifics of an approach to text that had been developing since the previously popular Tosafist method of dialectic had achieved its aims.Unlike R. Canpanton, R. Mazuz is fighting an uphill battle against dominant alternative forms of learning that he dubs pilpul.

The term pilpul translates literally as “sharpness” and can be used in a non-technical sense to describe a general way of looking at a text or problem, or it can be a technical term for a very specific type of methodology. (In the past, the expression was even used to refer to methods that were similar to or identical with that of R. Canpanton.) Moreover, the term’s connotation can be positive (if the speaker intends to point out the advantages it offers in solving complex problems), neutral, or negative (as in the present case). By juxtaposing the term to pilpul to the phrase “the innovation and breaking of logical constructions” and by making specific arguments against it, it is clear that R. Mazuz is using pilpul in a technical sense to describe a specific methodology or specific methodologies. While, in theory, R. Mazuz can be referring to any number of alternative methods, it is likely that his polemic is directed against the “Brisker” approach to Talmud study, an approach that will be discussed in the coming paragraphs. There is evidence to support such a contention.

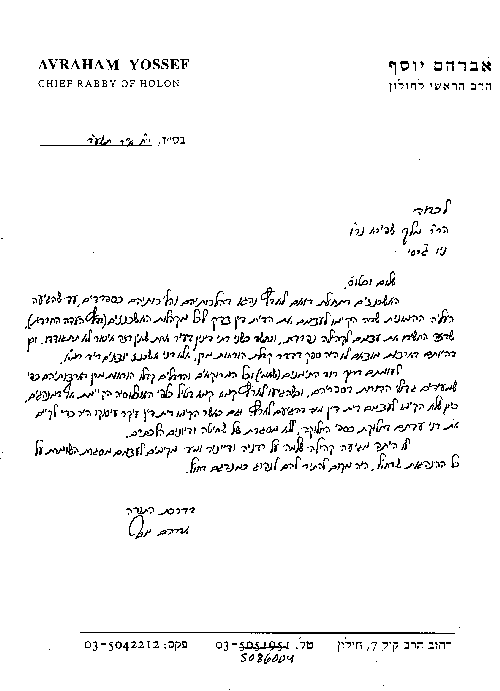

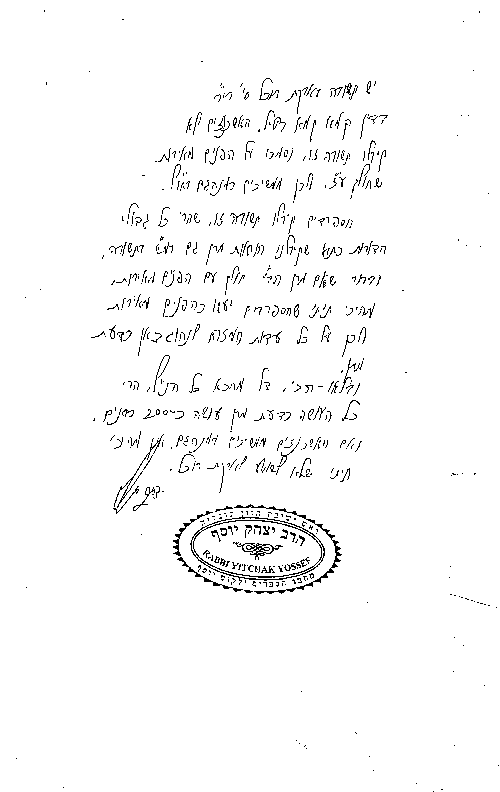

The first piece of evidence is R. Mazuz’s comments on R. Yehiel Ya’akov Weinberg’s critique of R. Chaim Soloveichik’s “Brisker” approach; these comments were posted by Marc Shapiro in

The Seforim Blog in the name of an anonymous

rosh yeshiva, but they are

in fact the comments of R. Mazuz. R. Weinberg accuses R. Chaim of inventing elaborate explanations of the Rambam and the Gemara that do not fit the language of the texts he is interpreting. In contrast, R. Weinberg praises the Vilna Gaon’s more simple analysis as reflecting the true meaning of the text.

[3] Upon seeing R. Weinberg’s critique, R. Mazuz responded that Yeshivat Kisse Rahamim uses the method of the Gaon of Vilna [rather than that of R. Chaim]. Thus, it is clear that R. Mazuz was including the

Brisker derekh in his critique of methods that, in his mind, failed to arrive at the original intent of the sources. The second piece of evidence is an interview conducted by David Lehmann and Batia Siebzehner. In this interview, R. Tsemah Mazuz (R. Meir Mazuz’s brother mentioned previously) claimed that, until about two hundred years ago, the methods of study used by Ashkenazim and Sephardim were the same. Apparently lacking knowledge of rabbinic texts and the history of rabbinic thought, these interviewers mistakenly suggest the possibility that he was referring to the onset of the Enlightenment. Rather, it is more likely that R. Tsemah Mazuz was referring to the flourishing of Ashkenazi

rabbanim such as Aryeh Leib ha-Kohen Heller (d. 1813, often known by the name of his major work,

Ketsot ha-Hoshen), Ya’akov Lorberbaum of Lissa (d. 1832, often known by the names of his major works,

Netivot ha-Mishpat and

Kehillat Ya’akov), and Akiva Eiger (1761-1837), who were pre-cursors to the Brisker school in terms of the type of analysis evident in their works. Third, because the paragraph under discussion functions as a contemporary polemic, R. Mazuz is most likely referring to the popular methods used in yeshivas today; the perception among many analysts is that a large proportion of the yeshiva system has been dominated by the Lithuanian Brisker approach and related methods. For a fuller understanding of R. Mazuz’s polemic, it is necessary to describe the general contours of the Brisker approach as they relate to R. Mazuz’s objections.

While a number of competing formulations exist for explaining the goals and methods of the “Brisker” approach, Norman Solomon’s is the most extensive. According to Solomon, proponents of the “Brisker” or “Analytic” approach [often referred to as “Briskers” in yeshiva

circles] seek to understand how various legal concepts that underlie a specific text operate. Consequently, Briskers develop every possible meaning they can think of for each concept within the text under discussion. They then re-read the text based on each of those meanings in order to figure out which understanding best sheds light on the subject. In doing so, they often encounter the contradictory ways in which the local text and alternatives sources seem to use the concept. In order to resolve the contradictions, Briskers create a hakirah, (in this case,

the term would best be translated as a “distinction” or “dichotomy”) in which they would argue that one concept can have different facets that express themselves in different situations. Note that, because these distinctions are often based on the contradictory implications of a concept rather than on a textual ambiguity, they do not flow “necessarily” from the text and are often speculative, an issue that is the crux of R. Mazuz’s critique.

Conclusion: The Re-Codification of Iyyun

R. Mazuz’s (re)-codification of Iyyun Tunisai functions as a way to make the method meaningful in the contemporary world. His descriptions of the method therefore lack the widespread use of philosophical terms so common among the original codifiers of Sephardic Iyyun. Instead, they focus on justifying the method through logical argumentation, which this article has already explored, and by reference to the perceived usage of this method by the great rabbis of the past, which lends legitimacy to his project. Even before embarking on his description of the method, R. Mazuz notes that his use of the phrase Iyyun Tunisai does not connote the geographical origin of the method, merely the fact that Tunisian rabbis took pride in perfecting it. He claims that the method was used in all of the classic schools of thought within the Jewish world, starting with the Geonim, moving on to the Tosafot and Rishonim, and lastly, by Maharsha, Rashash, and others, “who excel in the straightness and depth of the[ir] analysis.” Taken literally, this statement is misleading, as it lumps together rabbis with very different approaches to text. While Maharsha, along with many other Polish rabbis of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, did use this method, other commentators such as Tosafot were interested in harmonizing other contradictory texts with the local text through dialectical reasoning rather than focusing on literary issues within the local text – a process not conducive to simple readings of the local text. It is doubtful that R. Mazuz, who is fully familiar with these differences, intends that this statement be taken literally. Rather, the last clause of the sentence, which emphasizes the “straightness” (Heb. yosher) of the commentators’ analysis, is emphasized. The statement is a rhetorical device that situates Iyyun Tunisai within the mainstream of Jewish tradition. By mentioning that great Ashkenazi rabbis, such as Maharsha, used this method, Mazuz legitimizes its usage for Ashkenazi Jews as well, since, by rejecting the Analytic approach in favor of Iyyun Tunisai, Ashkenazi Jews would not be rejecting their own traditions but reclaiming the “Tunisian” tradition as their own, “going back,” as it were, to the “original” Ashkenazi tradition. In fact, other than the name Iyyun Tunisai and occasional mention of the Tunisian/Jerban community and its rabbis, there is no indication within the article that the method uniquely represents the global Sephardic tradition, as none of the early modern and late medieval Sephardic rabbanim, such as Canpanton or Shemu’el ibn-Sid (or Sidilyo or Sirilyo), are ever cited. Despite the fact that previous sections of this article have proven the method’s Sephardic roots and its historical

uniqueness, most of the rabbis cited in R. Mazuz’s essay are well-known, “classical” Ashkenazi and Sephardic/Jerban rabbis.

R. Tsemah Mazuz’s claim that, until about two hundred years ago, the methods of Talmud study used by Ashkenazim and Sephardim were identical should be analyzed more fully. One controversial hallmark of the “Analytic/Brisker” approach was the rejection of most of the

later Ashkenazi rabbis such as Maharsha, whose commentary, which often elucidates difficult passages in Tosafot, had been an essential part of the yeshiva curriculum in Ashkenazi lands. Instead, the “Analytic” school favored independent analysis of the classical Rishonim, especially Rambam’s Mishneh Torah, and rejected previous traditional methods of interpretation, and it was this rejection that was the subject of severe censure by critics within the Ashkenazi world. By showcasing the role of tradition in his argument for the revival of Iyyun Tunisai, R. Mazuz taps into this already ongoing debate and reveals that he is not fighting for the supremacy of the Tunisian Method merely within the Sephardic world, but within the yeshiva world in general. The revival of his method is therefore not a separatist attempt to preserve his own tradition (though it certainly encompasses that element) but a hegemonic approach that seeks to influence the entire religious world. R. Mazuz’s fight should therefore not only be analyzed “vertically,” as an expression of a line of Sephardic tradition, but also

“horizontally,” as one battle in an ongoing war against Brisk that dates back to the early years of the movement’s spread. This war has intensified in recent years, which have seen the supremacy of the “Analytic” method challenged by a number of alternative approaches. Therefore, the revival of the Tunisian method is a reflection of current socio-ideological developments within the broader Orthodox world.

The question, then, is what the prospects for Iyyun Tunisai and other similar methodologies may be. On the one hand, one might argue that, in order to successfully compete with Brisk, Iyyun Tunisai would need to allow for a certain amount of legal conceptualization inherent within the Analytic methodology, since such conceptualization captures the imagination of specific types of students who are attracted to Brisk. While questions focused on syntax and sentence structure would be too “basic” for such conceptualization, questions focused on turns of phrase and flow of text can more easily lend themselves to further conceptualization.

On the other hand, Iyyun Tunisai can serve as an alternative to the “Analytic” school precisely because it takes literary and historical elements into account, elements that are often ignored within the “Brisker” method. Iyyun Tunisai is ideal for those who want to develop textual skills, and its focus on basic grammatical and syntactic analysis will attract students who feel, as R. Mazuz does, that these elements should be studied before embarking on further analysis. Advanced students who are sensitive to literary structure and grammatical ambiguity will find meaning in the types of questions that Iyyun Tunisai encourages, questions that deal with unusual turns of phrase and that try to connect the different elements of the text. Critics of the Analytic School’s often a-historical approach to text would be pleased with R. Mazuz’s focus on close textual readings and critical analysis. Speaking of the original Iyyun ha-Sefaradi, Daniel Boyarin comments, “It is possible to say that, until the Historical-Philological School of later generations, there did not arise in Israel another house of study that applied with such scope the contemporary general scientific method to analysis of the Talmud.” While this claim may have held true then, strict modern-day historians hoping for a full academic approach would not agree with other assumptions upon which the method is based, most notably the assumption that the Talmudic sages and early commentators foresaw all possible alternate interpretations and rejected them. Yet this non-critical element is precisely the method’s strength. Most students in yeshivas would not be comfortable assuming that an Amora or Rishon should not be given the benefit of the doubt, and would likely view academic interpretations of a sugya as just as speculative as the very explanations that the academic approach purports to “correct.” Iyyun Tunisai strikes a balance between an overly-critical approach, which would undermine the legitimacy of the text under discussion, and an approach that is not self-critical enough to be able to discern between likely and forced interpretations. It is this balance that allows ha-Iyyun ha-Yashar to serve as an alternative to other methods of study current in the yeshiva world.