[1]: א״ל הקב״ה … יודע אני כוונתו של אהרן היאך היתה לטובה On a Short Wedding Wish to the Lichtensteins from the Pen of Rabbi Jehiel Jacob Weinberg

Wish to the Lichtensteins from the Pen of Rabbi Jehiel Jacob Weinberg

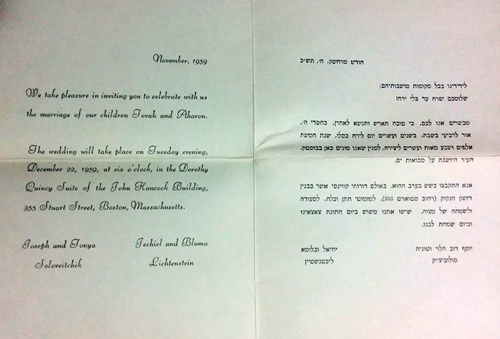

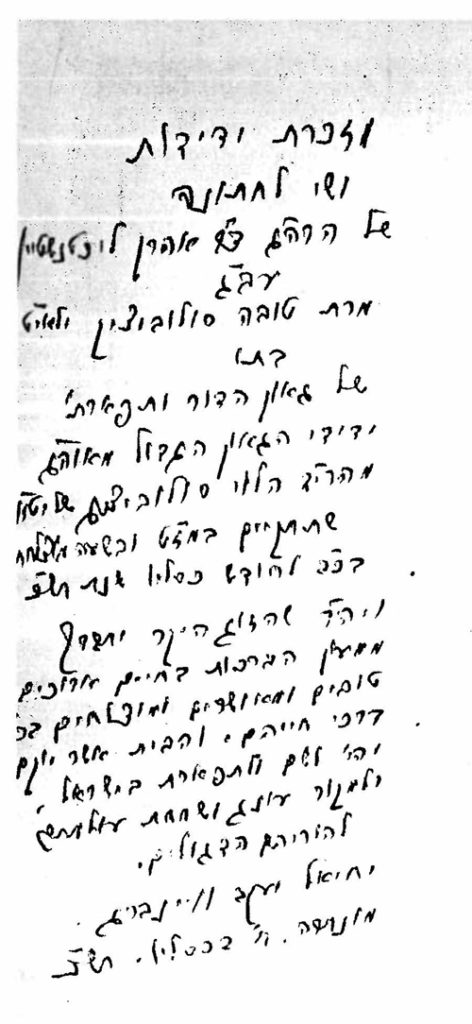

In anticipation of the joyous occasion, to which he apparently could not arrive in person, Rav Weinberg sent an inscribed volume of Yad sha’ul,[26] a collection of essays compiled in memory of his beloved talmid muvhak (and the person primarily responsible for bringing him to Montreux in the first place),[27] Rabbi Saul Weingort (ca. 1914–1946),[28] who had passed away following a tragic train accident while on his way to deliver a shi‘ur at the yeshivah in Montreux.[29] Through some serendipitous twist of fate, it is this copy of the sefer which made its way into the open stacks of the Gottesman Library. The dedicatory text (see Fig. 2) and my translation thereof follow:

A gift and token of friendship presented on the occasion of the marriage of the ga’on, Rabbi Dr. Aharon Lichtenstein, to his soul mate, Ms. Tovah Soloveitchik[31] – may their years be long and good – the daughter of this generation’s pride and splendor, my friend, the great ga’on and Luminary of the Diaspora, our teacher, Rabbi Joseph B. ha-Levi Soloveitchik – may his years be long and good, amen – which is set to take place, under a lucky star and at an auspicious hour, on 22 Kislev [5]720. May it be His will that this precious couple be blessed from the Abode of Blessing with long, good, and joyous lives and with success in all of their endeavors. And may the home that they build be of fame and of glory in Israel [see I Chron. 22:5] and a source of eternal delight and happiness for their distinguished parents.

Jehiel Jacob Weinberg

Montreux, 8 Kislev [5]720 [December 9, 1959]

between Rabbis Weinberg and Soloveitchik, two leading rashei yeshivah whose formative years were spent in both the Lithuanian yeshivah world and the German academy. We know from other sources that they first met while the Rav was a student at the University of Berlin in the 1920s; according to testimony cited by Rabbi Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, the Rav audited classes at Rav Weinberg’s Seminary during the 1926–1927 academic year.[33] Their encounters extended well beyond the classroom, however,[34] and even though Rav Weinberg was generally not enamored of the Brisker derekh ha-limmud espoused by Rav Soloveitchik and his forebears,[35] these two intellectual powerhouses maintained a deep appreciation for one another throughout their lives[36] – as can certainly be seen in Rav Weinberg’s above inscription.

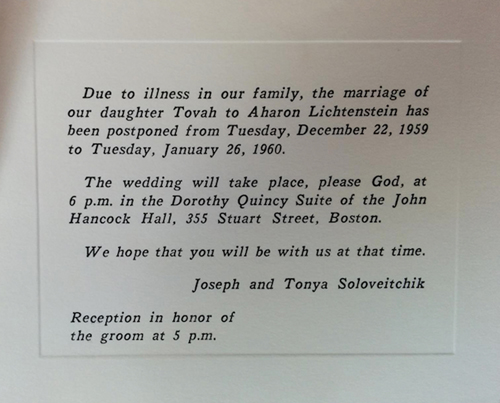

The second issue that I wish to discuss here relates to the date of the wedding itself. As of 8 Kislev 5720, Rav Weinberg, quite justifiably, thought that it would take place two weeks hence. However, that very evening, December 9 – the same night the Rav delivered the aforementioned (n. 35) hesped for his uncle, Rabbi Isaac Ze’ev Soloveitchik (1886–1959) – Rav Soloveitchik “informed his family that he had been diagnosed with colon cancer, and would be returning to Boston the next day for surgery. His daughter Tovah and her fiancé R. Aharon Lichtenstein postponed their wedding (which had been set to take place in the coming days) until a few weeks later, so that the Rav could participate.”[37] Thus, the wedding was not actually held until Tuesday night, 27 Tevet 5720 (January 26, 1960) (see Figs. 3 and 4),[38] something Rav Weinberg could not have predicted at the time he penned his wishes to the young couple.

Looking back over

the past 50 years, what I am proudest of is what some would regard as being a

non-professional task. I’m proudest of having built, together with my wife, the

wonderful family that we have. It is a personal accomplishment, a social

accomplishment, and a contribution – through what they are giving and will

give, each in his or her own way – in service of the Ribbono shel Olam in the future.[42]

I wish at the outset to express my appreciation to yedidi, Reb Menachem Butler, ne‘im me’assefei yisra’el, for furnishing me with the opportunity, as well as many of the bibliographical sources (including the primary text itself!) required, to compose this essay. Additional thanks go to his fellow editors at the Seforim Blog for their consideration of this piece and, generally, for their great service to the public in maintaining such an active and high-quality platform for the serious discussion of topics of Jewish interest. Finally, I am indebted to my friends Eliyahu Krakowski, Daniel Tabak, and Shlomo Zuckier for their editorial corrections and comments to earlier drafts of this piece which, taken together, improved it considerably.

[1] See Shemot

rabbah (Vilna ed.) to Parashat

tetsavveh 37:2.

[4] One set of verses to which maspidim kept returning when describing

Rav Lichtenstein was those that appear in Malachi 2:5-7, together with the

rabbinic interpretation thereof: “If a given rabbi can be compared to an angel

of the Lord of Hosts, let them ask him to teach them Torah, and vice versa” (Hagigah 15b, Mo‘ed katan 17a). See the hespedim

of Rabbis Mayer Lichtenstein here

(listen at about 7:50), Mordechai Schnaidman here

(listen at about 23:00), and my friend Mordy Weisel here

(listen at about 5:05). Similarly, others have described him as angelic without

specific recourse to the verses in Malachi; see the hespedim of Rabbis Mosheh Lichtenstein here

(listen at about 9:25) and Avishai David here

(listen at about 1:03:25).

[5] So according to Rabbi Mordechai

Schnaidman here

(listen at about 16:00); see also Yosef Zvi Rimon, “Keitsad magdirim gedol dor?”

JobKatif (May 4, 2015). Similarly,

Rabbi Ari Kahn compared Rav Lichtenstein to Rabbi Israel Salanter (1810–1883) here

(listen at about 9:00 and 48:55), and Mrs. Esti Rosenberg said that the stories

people tell about her father remind her of those told about Rabbi Aryeh Levin

(1885–1969); see her interview with Yair Sheleg: “Yaledah ahat mul 700 otobusim,” Shabbat: musaf le-torah, hagut, sifrut

ve-omanut 927 (May 15, 2015).

[6] See her hesped here

(listen at about 0:35 and 2:25).

[7] See the hesped of Mrs. Tanya Mittleman, Rav Lichtenstein’s youngest, here

(listen at about 10:15).

[8] See the hesped of Rabbi Nathaniel Helfgot here

(listen at about 46:55).

[9] See the hesped of my friend David Pruwer here

(watch at about 18:50).

[10] See the hespedim of Rabbis Mosheh Lichtenstein here

(listen at about 4:50), Mayer Lichtenstein here

(listen at about 12:35), and Assaf Bednarsh here

(listen at about 14:05), as well as the video produced in honor of Rav

Lichtenstein’s eightieth birthday here (watch at about

9:25 and 11:35) and that of a public conversation between Rabbi Benny Lau and

Rav Aharon and Dr. Tovah Lichtenstein on the topic of “Education and Family in

the Modern World” held in Ra’anana on May 13, 2012 here (watch at about

27:45 and 28:55). See also the recently-released essay “On Raising Children,” The Israel Koschitzky Virtual Beit Midrash

(May 2015), based on a sihah

delivered by Rav Lichtenstein in July 2007.

[11] See the video produced in honor of Rav

Lichtenstein’s eightieth birthday here (watch at about

11:25), as well as the hesped of Mrs.

Tanya Mittleman here

(listen at about 19:05) and Mrs. Esti Rosenberg’s interview with Yair Sheleg, “Yaledah ahat mul 700 otobusim.”

[14] See the hesped of Rabbi Shay Lichtenstein here

(listen at about 23:00). See also the hesped

of David Pruwer here

(watch at about 18:45), as well as Rav Lichtenstein’s “On Raising Children.”

[16] See the hesped of Mrs. Tanya Mittleman here

(listen at about 19:10).

[17] Ibid. (listen at about 10:30).

[18] See his hesped here

(listen at about 16:50).

[20] Rabbi Assaf Bednarsh recounted here

that when Rav Lichtenstein would call his wife on the phone, he would address

her as “darling,” rather than “rebetsin” (listen at about 14:35). (Dr.

Lichtenstein herself reminisced here about how her

husband would sometimes jokingly address her as “Mrs. L.,” and she, in turn,

would call him “Reb Aharon” [watch at about 1:10]). Noach Lerman talked here

about how Rav Aharon would open the car door for his wife when they drove

somewhere (listen at about 34:25). Similarly, see the video here for a picture of

husband and wife going rafting together (watch at about 12:22) and, of course,

the dedication Rav Lichtenstein inscribed at the front of his two-volume Leaves of Faith (Jersey City, NJ: Ktav

Pub. House, 2003–2004): “To Tovah: With Appreciation and Admiration.”

toward the institutions of marriage and family and how they square with more

modern conceptions, see his “Ha-mishpahah ba-halakhah,” in Mishpehot beit yisra’el: ha-mishpahah bi-tefisat ha-yahadut

(Jerusalem: Misrad ha-Hinnukh ve-ha-Tarbut – Ha-Mahlakah le-Tarbut Toranit,

1976), 13-30, esp. pp. 21-30; “Of Marriage: Relationship

and Relations,” Tradition 39:2

(Summer 2005): 7-35, esp. pp. 10-13 (reprinted here

in Rivkah Blau, Gender Relationships in

Marriage and Out [New York: Michael Scharf Publication Trust of the Yeshiva

University Press; Jersey City, NJ: Ktav Pub. House, 2007], 1-34, and in Aharon

Lichtenstein, Varieties of Jewish

Experience [Jersey City, NJ: Ktav Pub. House, 2011], 1-37); and “On Raising Children.”

[21] In the course of the aforementioned (n.

10) public conversation on the topic of “Education and Family in the Modern

World” here, Dr. Lichtenstein

recalled that at the berit milah of

the couple’s firstborn son Mosheh, her father, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik

(1903–1993), sensing that Rav Lichtenstein harbored grand aspirations to save

the world, spoke about the importance of the father’s role in raising his

children and not leaving the job solely to his wife (watch at about 26:00). See

Rav Aharon’s parallel account in “On Raising Children,” as

well as his comment there that “I feel very strongly about the need for

personal attention in child-raising, and have tried to put it into practice.”

[23] Shlomo Zuckier and Shalom Carmy, “An Introductory

Biographical Sketch of R. Aharon Lichtenstein,” Tradition 47:4 (2015): 6-16, at p. 7. His dissertation would

eventually appear as Aharon Lichtenstein, Henry

More: The Rational Theology of a Cambridge Platonist (Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press, 1962).

[24] According to my friend Jonathan Ziring, in

an e-mail communication dated May 28, 2015, the Lichtensteins first met, by

chance, at the home of Rabbi Ahron Soloveichik (1917–2001), the Rav’s brother

and another major influence on Rav Lichtenstein. The Rav would later encourage

Rav Aharon to court his daughter, and the rest, as they say, is history.

[25] Image courtesy of Naftali Balanson’s Facebook page, as brought

to my attention by Rabbi Jeffrey Saks.

[26] Jehiel Jacob Weinberg and Pinchas Biberfeld (eds.), Yad

sha’ul: sefer zikkaron a[l] sh[em] ha-rav d”r sha’ul weingort zts”l (Tel Aviv: The

Widow of Saul Weingort, 1953).

[27] See Rav Weinberg’s memorial essay,

“Le-zikhro,” printed at the beginning of Yad

sha’ul, pp. 3-19, at p. 13.

[28] The date of Rabbi Weingort’s birth seems

somewhat controversial. Rav Weinberg himself, in “Le-zikhro,” 4,

estimates that his student was born in either 5673 or 5674 (1913 or 1914),

whereas the frontmatter

of the Yad sha’ul volume gives the

precise date 12 Kislev 5675 (November 30, 1914); Marc B. Shapiro, Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy: The Life and Works of

Rabbi Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, 1884–1966 (London; Portland, OR: Littman

Library of Jewish Civilization, 1999), 161, claims he was born in 1915; and the website of the Yad Shaoul

kolel in Kokhav Ya’akov, opened in

2011 and dedicated in Rabbi Weingort’s memory, concurs with Shapiro.

[29] See Weinberg, “Le-zikhro,” 15.

[30] Most readers are probably familiar with

the more common Hebrew spelling of “Soloveitchik” with a final kof. Rav Weinberg, however, generally

preferred ending the name in a gimel

(except, strangely, in the case of the Rav’s daughter Tovah).

[31] Dr. Lichtenstein would go on to complete

her doctoral studies in social work at Bar-Ilan University following the

family’s arrival in Israel in 1971, writing her dissertation on “Genealogical

Bewilderment and Search Behavior: A Study of Adult Adoptees Who Search for

their Birth Parents” (1992). She is therefore referred to here without her

doctoral title.

[32] It should be noted that Rav Lichtenstein

served as coeditor of the rabbinic periodical Hadorom during the mid-1960s and, as such, may have been involved

in editing some of Rav Weinberg’s last publications to appear during his

lifetime. (For a partial bibliography of Rav Weinberg’s oeuvre, see Michael

Brocke and Julius Carlebach, Biographisches

Handbuch der Rabbiner: Teil 2: Rabbiner im Deutschen Reich, 1871–1945, vol.

2 [Munich: K. G. Saur, 2009], 639-640 [no. 2657]. For a fuller inventory, see Shapiro,

Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy, 239-246.) Discovery and analysis of any

potential remaining correspondence between the two during this period remain

scholarly desiderata.

[33] See Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, The Rav: The World of Rabbi Joseph B.

Soloveitchik, ed. Joseph Epstein, vol. 1 (Hoboken, NJ: Ktav Pub. House,

1999), 27 with n. 13. Similarly, see Shalom Carmy, “R. Yehiel Weinberg’s Lecture on Academic Jewish

Scholarship,” Tradition

24:4 (Summer 1989): 15-23, at p. 16.

[34] See Werner Silberstein, My Way from Berlin to Jerusalem, trans.

Batya Rabin (Jerusalem: Special Family Edition Published in Honor of the Author’s 95th

Birthday, 1994), 26-27, as quoted in Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, “Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik: The Early Years,” Tradition 30:4 (Summer 1996): 193-209,

at p. 197; idem, The Rav, 28; and idem, From

Washington Avenue to Washington Street (Jerusalem; Lynbrook, NY: Gefen; New

York: OU Press, 2011), 108 (available here).

[35] See his letter to Rabbi Jacob Arieli of

Jerusalem composed sometime after 2 Nisan 5711 (April 8, 1951), as reproduced

in Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, Seridei esh:

she’elot u-teshuvot hiddushim u-bei’urim be-dinei orah hayyim ve-yoreh de‘ah, vol. 2 (Jerusalem:

Mossad Harav Kook, 2003), 355-357 (sec. 144), at pp. 356-357; his letters to Dr. Gabriel Hayyim Cohn,

dated 27

Tevet 5725 (January 1, 1965) and 19 Kislev 5726 (December 13, 1965), as

reproduced in Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, Kitvei

ha-ga’on rabbi yehiʼel yaʻakov weinberg, zts”l, ed. Marc B. Shapiro, vol. 2

(Scranton, PA: Marc B. Shapiro, 2003), 219 n. 4 (esp. the latter one); and the

beginning of the selection from his eulogy for Rabbi Weingort printed in Yad sha’ul, 16. For a partial translation of the Rav’s famous hesped “Mah dodekh mi-dod,” which

originally appeared in Hebrew in Hadoar

43:39 (September 27, 1963): 752-759 and is referred to by Rav Weinberg in the

last letter cited above, see Jeffrey Saks, “Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik on the Brisker Method,” Tradition 33:2 (Winter 1999): 50-60.

Judith Bleich, “Between East and West: Modernity and

Traditionalism in the Writings of Rabbi Yehi’el Ya’akov Weinberg,” in Moshe Z. Sokol

(ed.), Engaging Modernity: Rabbinic

Leaders and the Challenge of the Twentieth Century (Northvale, NJ;

Jerusalem: Jason Aronson Inc., 1997), 169-273, at p. 239; Marc B. Shapiro, “The Brisker Method Reconsidered,” Tradition 31:3 (Spring 1997): 78-102, at

p. 86, with n. 25; idem, Between the

Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy, 194-195, with nn. 95-98; and Nathan

Kamenetsky, Making of a Godol: A Study of

Episodes in the Lives of Great Torah Personalities, vol. 1, 1st

ed. (Jerusalem: Hamesorah, 2002), 432-433. See also Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits’

assessment of his teacher’s derekh

ha-limmud in “Rabbi Yechiel Yakob Weinberg zatsa”l: My Teacher and Master,” Tradition 8:2 (Summer 1966): 5-14, at

pp. 5-10. For Rav Lichtenstein’s own reflections on the types of criticisms of

the Brisker derekh expressed by Rav

Weinberg, see his “Torat Hesed and Torat Emet: Methodological Reflections,”

in idem, Leaves of Faith, 1:61-87,

esp. at pp. 78-83, as well as an earlier version of this essay cited in

Shapiro, “The Brisker Method Reconsidered,” 93-94. (I am indebted

to Eliyahu Krakowski for bringing the Kamenetsky and Lichtenstein references to

my attention.) See also Aharon Lichtenstein, “The Conceptual Approach to Torah

Learning: The Method and Its Prospects,” in idem, Leaves of Faith, 1:19-60, esp. at pp. 43-44, 48-50.

“Rabbi Moses Soloveitchik” in Rav Weinberg’s published works, excluding those made

in the above letters, generally refer not to the Rav’s father (1879–1941) but

to his Swiss first cousin (1915–1995), son of Rabbi Israel Gerson Soloveitchik

(1875–1941), son of Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik (1853–1918).

[36] Indeed, Rav Weinberg would consistently

refer to the Rav in writing by his honorific rabbinic handle, “Ha-g[a’on]

r[abbi] y[osef] d[ov],” or a variant thereof (as in our case); see his Seridei esh, 2:196-201 (sec. 78),

at p. 198 (dated 29 Adar 5716 [March 12, 1956]), and idem, Kitvei ha-ga’on rabbi yehiʼel yaʻakov weinberg, zts”l, 219 n. 4. According to Shapiro, Between the Yeshiva World and Modern

Orthodoxy, 163, Rav Weinberg also contacted the Rav after the War to seek

his assistance during his long recovery.

record with which I am familiar is a bit more reticent, although Rabbi Howard

Jachter reports the following in the context of a discussion of the prohibition

of kol ishah and Rav Weinberg’s

now-famous lenient ruling on the question:

asked Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik in July 1985 whether he agrees with this

ruling of Rav Weinberg. The Rav replied, “I agree with everything that he

wrote, except for his permission to stun animals before Shechita” (see volume

one of Teshuvot Seridei Eish). Rav Soloveitchik related his great appreciation

of Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg. Rav Shalom Carmy later told me that Rav

Soloveitchik and Rav Weinberg had been close friends during the years that Rav

Soloveitchik studied in Berlin.

Literature (New York: Ktav Publishing House, Inc., 1977), 183-189; Bleich,

“Between East and West,” 260-261, 271-272;

and Shapiro, Between the Yeshiva World

and Modern Orthodoxy, 117-129, 192. For Rav Soloveitchik’s own involvement

in questions relating to the humane slaughter of animals, see Joseph B.

Soloveitchik, Community, Covenant and

Commitment: Selected Letters and Communications, ed. Nathaniel Helfgot

(Jersey City, NJ: Toras HoRav Foundation, 2005), 61-67.

[37] Jeffrey Saks, “Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik and the Israeli Chief

Rabbinate: Biographical Notes (1959–60),” BDD 17 (September 2006): 45-67, at p.

53.

[38] Fig. 3 is courtesy of Naftali Balanson’s

Facebook page, as

brought to my attention by Rabbi Jeffrey Saks. Fig. 4 derives from the video

produced in honor of Rav Lichtenstein’s eightieth birthday here (watch at about

1:03). (I am indebted to Rabbis Dov Karoll, Jeffrey Saks, and Reuven Ziegler

for confirming some of the details of the Lichtenstein wedding for me.)

[39] See the interview with Rabbi Dov Karoll

on Voice of Israel here

(listen at about 2:55). See also the hesped

of Rabbi Mosheh Lichtenstein here

(listen at about 5:15). Similarly, at a sheloshim

event held at the Hechal Shlomo Jewish Heritage Center in Jerusalem on May 18,

Mrs. Esti

Rosenberg, in speaking of her father’s self-identification with the Levites as

the prime exemplars of ovedei Hashem par excellence, commented that just as the

Levites were netunim netunim to Aaron

and his sons in Parashat be-midbar (Num.

3:9) (which also happened to be Rav Lichtenstein’s bar mitzvah parashah), so was Rav Aharon completely

dedicated to his family. See the video here (watch at about 11:40). And for a

visual representation of just how central avodat

Hashem was to Rav Lichtenstein’s core identity, see the photograph of his matsevah posted to Yeshivat Har Etzion’s

Facebook page.

[40] From a forthcoming article to be published

in Jewish Action.

[41] See his hesped here

(listen at about 10:30).

[42] See Rav Lichtenstein’s interview with

Yaffi Spodek: “Reflecting

on 50 Years of Torah Leadership,” the

YUNews blog (October 11, 2011). Similarly, see this video produced in honor

of Rav Lichtenstein receiving the Israel Prize in 2014 (watch at about 10:20),

as well as the hespedim of Mrs. Esti

Rosenberg here

(listen

at about 8:45) and Rabbi Baruch Gigi here (listen at about 16:30) and the

former’s interview with Yair Sheleg, “Yaledah ahat mul 700 otobusim.” Finally, see Rav Lichtenstein’s sihah “On Raising Children,” where

he states unequivocally: “There are very few people about whom it can […]

genuinely be said that there is something objectively more important in their

life than raising children.”