The Chief Rabbi of Amsterdam: A Jewish Convert

R. Yitzhak was extremely successful in his studies and was widely respected within the Amsterdam community; so much so, that when he attempted to move to Israel, R. Saul (ben Aryeh Löb) Löwenstamm (1717-1790) – then Chief Rabbi of Amsterdam – convinced him not to for the sake of the Amsterdam community. R. Yitzhak was for a short period of time a gem cutter, after which he moved to full time study and working. After R. Löwenstamm died, R. Yitzhak became the interim chief Rabbi of Amsterdam. Later, he became the Chief Rabbi of a new synagogue in Amsterdam, Adat Yeshurun. As this was a new synagogue, there were some from his old synagogue who were upset with the move. R. Yitzhak was known as “Yitzhak the Ger” (Yitzhak the Convert), some members of the old synagogue began referring to him instead as “Yitzhak Getz” (Yitzhak the Fool).

R. Yitzhak died in 1807 and his epitaph reads as follows:

זאת מצבת קבורת אדונינו מורנו ורבינו אב”ד ור”מ דקהלתנו, הנודע שמו בישראל בשם הגאון הצדיק החסיד מוהר”ר אהרן משה יצחק בן כ”ה אברהם זצוק”ל. רועה צאן עדת ישרון, גאה וגאון השליך נגדו, הצנע היה לכתו, רק לאמונה גבר בארץ, להורות עם ה’ את הדרך ישכון אור, להטות לבבם ליראת ה’ כל הימים, ולגלות למסור אזנם, ויקם עדות ביעקב ותורה שם בישראל, אף אם הציון הלז יכסה את גויתו, אהבתו תשאר תקועה

בלבנו, כי בזרע יצחק עוד יאיר שמשו ואור חכמתו ותורתו לעד בעולםThis is the monument of our master, our teacher, our Rabbi, the Chief Rabbi and Teacher of our community, who is known as the great one, pious, and righteous Rabbi Aharon Moshe Yitzhak son of the wise on Avraham ztsuk”l. The leader of Congregation Adat Yeshurun, the great and high one, who was humble in his ways, his relied upon faith, and taught the path to light, to lead their hearts to fear God all their days, and to reveal the ethical path to their ears, and he upheld the congregation and gave Torah to Israel, even though this monument covers his body, our love for him remains in our hearts, with the seed of Yitzhak will still guide by his light, and his light of wisdom and Torah will remain forever.

There appears to be but one depiction of R. Yitzhak, a statue of him which unfortunately disappeared during the Holocaust. The statute is reproduced on the side and as you can see his book, Zera Yitzhak, is also included next to the statute.

Sources: For biographical information see: Shmuel Yosef Fuenn, Kenesset Yisrael (Warsaw, 1886), entry R. (Ahron Moshe) Yitzhak b”r Avraham Graanboom; A. Ya’ari, “R’ Yitzhak ben Avraham haGer” in Mizrach u’Ma’ariv 5 (1931), 323-325. On converts who were involved in other aspects of Hebrew books, see A. Ya’ari, Mehkere Sefer (Jerusalem 1958), 245-255. The picture of R. Yitzhak as well as some biographical information is taken from Mozes Heiman Gans, Memorbook: History of Dutch Jewry from the Renaissance to 1940 (Netherlands, 1977), 291. Aside from R. Yitzhak’s Zera Yitzhak, he also composed a song for the inauguration of the Synagogue of Adat Yeshurun which was published in 1797 and is titled Zot Hanukat HaBayit.Appendix:

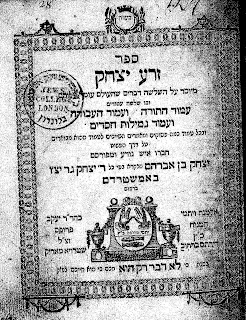

Zera Yitzhak (Amsterdam, 1789)