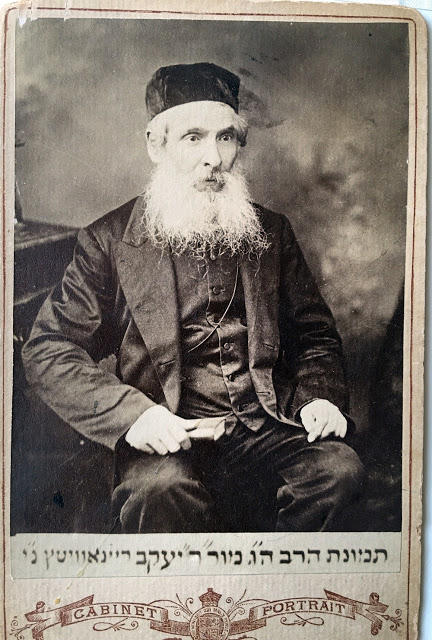

Zvi Hirsch Masliansky:

Memoirs from the Hebrew Periodical Ha-Doar

By Zviah Nardi

Introduction.

Zvi

Hirsch Masliansky, known as “The National Preacher” (1856-l943), was a member of

the Hibbat Zion movement in Russia from the time of its inception in l882, and served

as its itinerant preacher in the early 1890s. After his expulsion from Russia

in 1895, he went to the United States, where he became a leading figure in the

integration of the mass immigration of Eastern European Jews to American life.

He wrote memoirs of those two

periods of his life in the l920s. Published in Yiddish in 1924, they were followed

by a Hebrew version, for which the author was also responsible, in l929. The

family has recently published an English translation: Memoirs; an account of

my life and travels, Jerusalem, Ariel, 2009, which has been distributed to

family and friends, as well as to leading libraries.

In the l930s Masliansky wrote

another memoir, which was published in installments in the Hebrew periodical

Ha-Doar, mostly in vols. 13-14, 1933-5; four segments in vol. 15 and one, which

has been translated into English and incorporated into the English 2009 book,

in vol. 16 (1937).

The focus of these memoirs is far

more personal then that of the book. Here Masliansky describes his childhood,

his education, the early stages of his career and his marriage. Other segments

focus on various people he knew and loved back in Russia, including some great

Rabbis and important public figures.

Despite their literary quality

and importance to social history, these memoirs, hidden in the large bound

volumes of Ha-Doar, are even less known to the public than those published in

the book. A number of excerpts from the Ha-Doar memoirs have been translated by

Zviah Nardi (co-translator of the 2009 English book) for the benefit of family

members. To the best of our knowledge, this is their first English version. The

unpublished continuation of these memoirs in Masliansky’s handwriting is in

possession of the family.

We are most thankful to Eliezer

Brodt of the Seforim blog for putting this partial translation on the web, and

thus making it accessible to all interested in Zvi Hirsch Masliansky and in the

life of the Jews in the Pale of Settlement in the late 19th century.

We are also thankful to Moshe Maimon for bringing us together, and reviewing

the excerpts. We hope to continue the translation of both the published and the

hand written material in the future, and propagate them in the same fashion as

the work continues.

Finally, I would like to conclude

with a personal note: In 2006, four of our progeintor’s descendants made the

decision to publish his memoirs in an English version: his grandsons James and Marshall Weinberg of

New York and his great- granddaughters Zviah Nardi and Meira Nardi Bossem of

Jerusalem. As these excerpts of his second memoir from Ha-Doar appear on the

web, only two of us remain. My dear cousin-once-removed James Weinberg, a

businessman and prominent Jewish leader, passed away in October 2013; my dear

sister, Meira, just a year ago (on kaf-gimmel Tamuz). Meira was the first

reader of both memoirs as the work progressed — a wonderful first reader and

advisor. We would appreciate the

willingness of our readers to join us for a moment of thought about our dear

departed.

Zviah Nardi, Marshall Weinberg.

For further details contact znardi@bezeqint.net.

Excerpts from Masliansky‘s

Second Set of Memoirs,

Ha-Doar, 1933-1935.

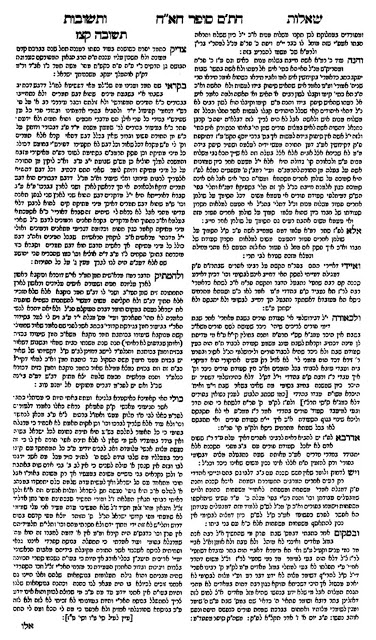

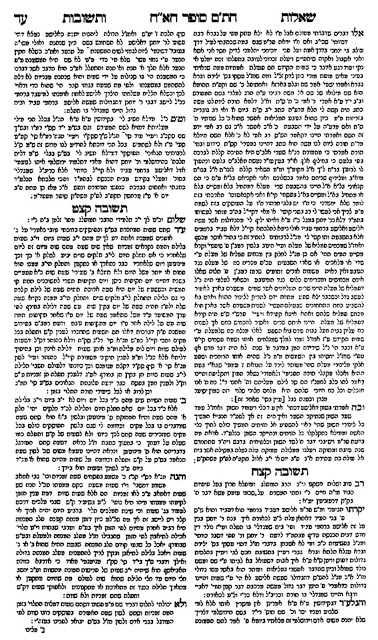

Ha-Doar vol. 13, 1933-4,

no. 38, p. 724

“Tachlith” – In search for

a purpose in life.

(A Chapter from my Memoirs)

My days as a “Yeshivah Bochur” [student at a religious academy], those

“days” devoid of goal and practical purpose, have come to an end. I felt a growing aspiration to study at the

modern, government-authorized Teachers’ Seminary in Zhitomir. I walked from

Novogrudok to Pinsk, where I planned to board a ship headed for Kiev on the

river Dnieper, and then walk from Kiev to Zhitomir.

“Tachlith, Tachlith”

[purpose, purpose] – this word sounded in my ears day and night, as I walked

and as I sat, as I ‘lay down and as I got up’. What will be my purpose in life,

what will become of me? I do not want Rabbi Yosel the Dayan [judge

according to religious law] as a role model, nor do I want Rabbi Eliezer the

preacher or the fanatical ascetic who tore the [modern Hebrew] novel “Ashmat

Shomron” [by Avraham Mapu] to shreds. This problem gave me no rest and kept

buzzing in my mind like the proverbial mosquito in the head of Titus. I had

dwelled long enough among fanatic savages. I am a grown boy, fifteen years old,

and back in my native town of Slutsk my mother, the elderly widow, is suffering

hunger, and she and my orphaned brother of eleven years, are expecting my help.

And what is my purpose in life? Tachlith! Tahclith! – the

cry was echoing inside me at that time as I walked along the road.

I became weaker by the hour, and

when I reached Mir, I felt that I should give my weak body and my swollen feet

a rest; I shall rest and then continue my quest for a purpose.

I was drawn to visit the Yesivah,

I so loved and adored, once more. I found this “molder of the nation’s spirit”

in fine order. Hundreds of students were chanting their gemorrah lessons

in loud voices. I found my cousin Avraham Yitzhak Masliansky[1] son of my

uncle Arieh Leib there (I used to call him ABIM in my letters). Our meeting was

one of loving excitement, as we had not seen each other since I had left

Slutsk. He told me that my younger brother Avraham was in Mir as well, studying

at the Talmud Torah [elementary school.] I was excited and moved to hear

this, and soon hugged and kissed my brother, and yet I said to myself with a

broken heart: “my miserable mother, you have lacked twice – a widow who is now

also bereaved of her children; left behind by both your sons.”

My cousin ABIM and I went to

visit our teacher Rabbi Chaim Leib[2]. He received

me cordially and discussed various issues with me. I did not tell him my

destination, as I did not wish to aggravate him. He suggested I return to the Yeshivah

and promised to provide for all my needs. My heart was indeed inclined to

accept his offer, but my mind reminded me “Tachlith!” I thanked him, he

blessed me, and I left the Yeshivah, with a heart full of longing.

After two days of rest I took my

wandering staff in my hand and put my sack on my back; my relatives escorted me

to the main road where we kissed each other and parted in tears.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Ha-Doar, vol. 14, 1934-5,

no.1, pp. 8 – 9.

Pinsk

(a Chapter from “My Life.”)

Two Yeshivah students

seeking a purpose in life are walking along the main road leading from Kapulya

to Pinsk. They walked for six days and ‘in the seventh day’ they arrived in

Pinsk; they came to this foreign city, where they had neither a relative nor ‘a

redeeming kinsman,’ with sore feet but with courageous spirits and high hopes. The city of Pinsk at the time excelled in its

commerce more than any other city in Lithuania. Along the river Pina, a

tributary of the Dnieper, its ships sailed to Kiev, Kremenchuk, Yekaterinoslav

and Odessa. We immediately noticed the difference between Pinsk and the surrounding

cities. The city was full of life and tumult, being the center of commerce for

grain and lumber shipped to the south of Russia by boats and rafts. Thousands of peasants bringing their

commodities filled its streets causing this turmoil.

At that time there were a number

of rich families living in Pinsk that were renowned throughout Russia. I am

referring to the Luria, Zeitlin, Eisenberg and Greenberg families, all had

among them learned men skilled in Torah and wisdom [secular studies]. The most

illustrious family were the Lurias, descendants of Rabbi Shlomo Luria (the

MaHaRSHaL) or of the Holy Ari [the mystic Rabbi Yitzhak Luria Ashkenazi.] They

excelled in both looks and character, in their skills and in their communal

work for charitable institutions, hospitals, Talmud Torah schools,

orphanages and homes for the elderly. The head of the family at that time was

the generous lady Haya’le Luria with her sons Moshe and David, and their sons

Aharon and Isar and sons-in- law Moshe Haim Eliasberg and Jonah Simchovitch of

Slutsk, all of them renowned Talmidei Chachamim [famous for their Jewish

knowledge.]

Pinsk is divided into two cities

– Pinsk and Karlin…

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Suddenly I received a letter from

Slutsk, informing me that my abandoned, widowed mother and my orphaned brother

are suffering cold and hunger. And so, what was I to do?!

This was an awful quandary and I

was totally hopeless. There were no Yeshivoth in Pinsk, and its

residents were unfamiliar with the practice of “eating by days” [having Yesivah

students eat in a different resident’s home each day], a practice I myself was

sick and tired of. Traveling any longer without documents had become impossible

[as the authorities were kidnapping men and boys for prolonged military service

in the area.] My friend Benyamin bid me goodbye and returned to his native town

of Poltava. Our parting was a heart wrenching sight. Little Jews, almost

children, deserted and alone, hugging and kissing each other, weeping and

sobbing on each other’s necks, separating from one another, devoid of hope to

find their purpose in life…

Absentmindedly I entered a Jewish

inn on the bank of the Pina River. The innkeeper, a man by the name of

Katchinovsky, was educated and respected students of the Torah. He took one

look at me and instantly liked what he saw. The inn served the rural Jews, the

tavern leasers and operators, living in the countryside around Pinsk. One of

the guests, a man of stature, had asked the inn keeper whether he knew of a

young man, a Torah student, who would agree to travel to the village with him

to be a melamed [teacher] for his children. It was summer, the first day

of the month of Tamuz, with three months left for the school year; He

was ready to pay thirty rubles for this period and to raise the salary for the

next year, provided he was satisfied with the man’s performance as instructor

and teacher for his children. The innkeeper turned to me and asked me if I

would agree to go with the man? I agreed.

Two days later the villager Eliezer

Rubinstein took me to his village of Harinich. He was a kind and honest man by

nature, and regarded me as a son from the very first day, treating me in a

loving and friendly manner: it was as though his heart foretold that in two

years time I would be his son-in-law.

The trip from Pinsk to Harinich

lasted for about four hours. On the way he started couching me in his own

manner. He clarified that country life was simpler and healthier than life in

the city. He proved ‘with signs and marvels’ that country people are healthier

physically and of a more honest spirit than city folk. He advised me to get

slightly more accustomed to physical work, to take long walks, gain strength

and ride a horse. ‘He said and acted’[3].

A horse he had bought in Pinsk was running behind the carriage; he put me on

the horse and I rode behind the wagon.

My heart was pounding rapidly for

the first ten minutes – the heart of a Yeshivah student who had never

touched a horse, and was suddenly studying the theoretical Talmudic issue of

‘the rider and leader’[4] in practice.

But I made the effort, straightened my neck, raised my head and rode like a

cossack in the regiment. He was surprised that I sat on the horse and rode

securely, as though accustomed to doing so, and expressed his feeling with the

Jewish proverb: “wer Torah, dort ist chochmeh!” [“Where there is Torah there is

wisdom!”]

As we were traveling I started to

understand what the world famous “Marshes of Pinsk” were. I had searched for

them in Pinsk without success, for Pinsk itself is a fine and dry city – no

swamps to be found in its streets, which stone-pavements are superior to those

of the neighboring towns. En route,

however, I learnt the nature of the terrifying swamps of Pinsk.

These swamps have gained their

widespread reputation for a good reason. They were large broad and deep,

extending for hundreds of miles… The roads, covered with branches of Birch and

Oak trees, were called “grebliyes’, and woe to the man or horse who took

one slanted step and got their leg into the ‘grebilyeh’ branches.

I rode my horse with the utmost

care and after a number of hours we reached a wonderful and beautiful place in

the wilderness of the swamp – thick forests, green fields, planted gardens,

pastures with sheep and cows grazing. Suddenly I saw a windmill far away, its

large, broad wings spinning fast.

Reb Eliezer Rubinstein turned to

me most happily and said: “Do you see, Hirsch’le, the mill, the house next to

it and all these fields till the distant mountain? – All this is mine. We are

now in our home in the village of Harinich.”

Ha-Doar, vol. l4, 1934-5,

no. 4, pp. 61-62

In the Country

(A Chapter from “my Life”.)

It was evening. The sun was

setting in the west, earth and sky kissed each other in a sea of molted gold;

the mill and the small hills around it were glowing in red. The air was full of

the delicate sounds of bells, the bells of herds returning from pasture. The

farmers’ wives were waiting for the herds, pails in hand, while the dogs, who

had spent the entire day with the flocks, were running and jumping towards

them, barking happily as their work day had ended and the time for rest had

come. Farmers, large and small, men and woman, all dressed in thick cotton

shirts, barefoot and tired, were returning, group by group, from their labor in

the fields to their small low houses covered with straw, there they were met by

their virtually naked toddlers and children, who rushed into the arms of their

mothers they had missed so.

“Good Evening!” called the head

of the family, as he opened the door of his dwelling wide.

The mistress of the house with

her children, who were waiting for their father and for the new teacher,

surrounded me. Six pairs of lovely eyes measured me with their glances from

head to toe.

Mrs. Devorah Rubinstein, a pretty

and graceful woman of about thirty, stood by her husband and looked at me with

a mother’s eye…

“Children!” – the head of the

household turned to his sons and daughters, two boys and three girls, the

oldest among them twelve years old, “say hello to your new teacher, he will

instruct you and you are obliged to obey him and follow his orders.”

The children approached me

respectfully and handed me their little hands, Yetta, the oldest, lowered her

glance as she came to me, as though her heart told her that it would not be

long – in three years time[5] – before

relationship would far exceed that of teacher and pupil…

I enjoyed my first meal and ate

it with zest. For the first time in my life I felt that I was eating my own

food. I then slept peacefully through the night. The next morning I examined my

pupils and saw that the two boys had studied a bit, but the girls did not even

know the [Hebrew] A-B-C. I started to work and within a number of weeks my

pupils were doing well in their studies.

The rural Jews living near

Harinich heard my praise from Reb Eliezer and came to see me. Some of them

brought their small children who joined my pupils, so that my salary doubled. I

was ever so happy when, for the first time, I sent my poor mother ten rubles.

That was a holy and festive day for me and I shall never forget it.

And yet the question of “tachlith”

remained unsolved – what will my life purpose be, what will my future hold? I

am living here, in a remote and deserted village, far from the rapid pace of

life, surrounded by peasants with whom I have no spiritual bond. They regard me

as worthless, an idle person who does not really work for a living, and I –

living here I shall forget everything I have learnt. I am but fifteen years

old, what will my purpose in life be? I will grow and develop in body but when

will I see to my soul and spirit…?

A Jewish tavern leaser in one of

the villages not far from Harinich had a small library. His name was Reb

Yitzhak Rutzky. He was a Torah scholar and knew Hebrew. After we got to know

each other he was pleased with me and opened up his library so I could take

whatever I needed. This encouraged me to continue my studies of the Talmud with

great desire. But a complete Jew does not live by Talmud alone. I felt, that

with all my proficiency in the Holy Writings my knowledge of Hebrew grammar and

medieval literature, which I knew only by name, was lacking. I searched through

the small library and found “The Guide to the Perplexed” and “The Principles”

[by Maimonides], “The Kuzari” [by Yehudah ha-Levi] and “Chovot Ha-Levavot”

[ by Behya ibn Pequda]. I fell upon these profound books overzealously and

enjoyed their study. I asked Mr. Rubinstein to bring me three books I wanted

from Pinsk: “Talmud Leshon Ivri” [a grammar of the Hebrew language by Judah Leib Ben Zeev], the

Biblical book of Isaiah, translated into Russian by Yehoshua Steinberg, and “Sefer

Ha-Brith.”[6] These books

occupied much of my time and I did not go idle.[7]

I studied the “Talmud Leshon

Ivri” most diligently from beginning to end, including the appendix by the

poet Adam HaCohen Lebensohn, and became quite a grammarian writing notes on the

margins of the book. The book of Isaiah in its Russian translation was

extremely useful: I imitated the first generation of Maskilim [adherents

of modern Jewish learning, Haskalah or Enlightenment] who learnt the

German language from Mendelsohn’s translation and commentary of the Bible [Bi-ur],

till I was able to read Russian with the help of a dictionary and thus read the

great works of Russian literature in the original.

“Sefer Ha-Brith“ (“The

Book of the Covenant” which includes tenuous information in all the branches of

science known at its time, carried me off to another world. Later on, however,

I learnt that the author of the book was a Yeshivah student like me, who

had never studied the natural sciences he was interested in, and yet wrote

modestly: “And I shall now confront Master Copernicus.”

And yet, I am grateful to the

author of this book. He was extremely important to me, a rural melamed,

with no school, no guidance. He opened my eyes to see that there are sciences

and important topics in this world that are worth learning.

My employer’s affection towards

me grew daily. He would sit at the table while I taught my students and audit

the lessons most eagerly; he secretly repeated the verses till he knew them by

heart. He especially liked the sayings from the Book of Proverbs about

“jealousy”, “hatred”, “lust”, and “honor”, but his favorite theme was

“idleness”, for he detested the lazy with all his heart, and so he always liked

to recited the 24th chapter of Proverbs out loud: ‘I passed by the

field of a lazy man, by the vineyard of a man lacking sense. It was all

overgrown with thorns; Its surface was covered with chickweed. And its stone

fence in ruins. I observed and took it to heart; I saw it and learned a lesson.

A bit more sleep, a bit more slumber, a bit more hugging yourself in bed, and

poverty will come calling upon you, and want, like a man with a shield.’

When he finished reciting the

original Hebrew he started translating it to Yiddish with the same chant and

intonation I used with the students. He continued to “recite” these verses till

we arrived at his mill, where he took me nearly every day after the lessons. He

taught me how to adjust the wings towards the wind and how to help him

inside. I especially liked sitting in

the mill during the evening hours, a highly suitable time and place to engage

in thought and to recite the declinations of Hebrew verbs to the rhythm of the

large grinding stones. And so I worked as a teacher by day and as assistant

miller by evening.

Some evenings I would stay long

hours at the mill, keeping the miller company till midnight. He was an elderly

Catholic peasant, very loyal to his faith. He loved me and felt sorry for me,

not being member to his religion. He told me as a fact that the Pope is

immortal and that old age has no power over him. He is like the moon, born

again every single month, and will never die.

The hours I spent with this innocent

old man were amazing and mysterious. The silvery moon, the rustle of the wings

of the mill, the noise of the large grinding stones as the aged man related his

stories, his nonsensical, imaginative stories enveloped in secrets and

mysteries. We pitied one another – he pitied me for my heresy and I him for the

figments of his hallucinating spirit, which he believed in with all his heart.

Ha-Doar, vol. 14,

1934-1935, no. 5, p. 79

A groom living in his

father-in-law’s home

(A chapter from “My Life”)

It was a bright pure spring day –

the third day of the third month of the year 5734 (1874), my birthday – I am

seventeen years old! I finished teaching

my pupils at noon. The sun stood high in the sky blessing the entire universe

with majestic splendor. My employer, Reb

Eliezer Rubinstein, stretched out his strong warm hand, kissed me and

congratulated me in honor of my birthday. He then took me by the arm and walked

with me down the narrow path leading to the hay fields he had been leasing from

the Pravoslave priests for more than twenty years. We reached a small lovely

hill; the grown hay gave a pleasant scent; the grass was sparkled with blue and

yellow flowers that seemed like little stars in the green sky beneath us.

We were walking very slowly when suddenly

Mr. Rubinstein halted and started to recite his favorite verses from the Book

of Proverbs: ‘I passed by the field of a lazy man, by the vineyard of a man

lacking sense’ etc. When he completed

reciting the verses he held me by my right arm and looked at me lovingly for

several minutes, then spoke as a man restraining his emotions.

“You know, Hirsch’le, that I love

you very much, and so my words will come from a pure and loyal heart. You are

seventeen years old today, may you live to a hundred and twenty, it is time for

you to find “tachlith”, to seek a purpose in life. You, with all your

talents, have not been destined from birth to be a melamed. And so I

have a wonderful proposition for you, if God helps me to accomplish it: You

should get engaged to be married to a kind hearted and pretty girl, daughter of

honest and wealthy parents and become betrothed this very day. And next year,

when you will be eighteen years old, you will marry at the very age established

by our sages of blessed memory. If you take my advice I shall congratulate you

on this very day and say ‘Mazal tov’ upon your engagement.”

He then was silent, looked me in

the eye and awaited my answer. His innocent and kindhearted monologue made a

great impression on me. Some minutes later I said: “Reb Eliezer, two sides are

needed for a shiduch [match] and I’m but one. Where is the other side?”

“Quite so, my son!” he answered,

“The other side is standing before you, and I am ready, and my eldest daughter,

Yetta, agrees full heartedly, because she loves you. I shall not sing her

praises in your ears, for I am her father, but I believe that you have eyes to

see and a mind and brain to understand. You can see her beauty and understand

that she shall be a ‘woman of valor’ and a ‘splendid crown’ on her husband’s

head. She is fourteen years old, as lovely as an eighteen year old and as wise

as a twenty year old. What then have you to say as it is the shadchen

[match maker] who is speaking to you.”

“Yes, Reb Eliezer, you mentioned

the word ‘tachlith’. Do you know that it was ‘tachlith’ that

uprooted me, that tore me away from my studies and from city life and brought

here to seek my livelihood? The question

of ‘tachlith’ is to become even more difficult now: what ‘tachlith’

will we have now if I marry and have a family?”

“Yes, my son,” he answered, “you

are right, but with God’s help I will find a solution to the problem. Open your

eyes and see this entire plain that brings me a yearly profit that could easily

support two families. I have leased all these fields for many years,we will

both live and work together. You will no longer be a ‘melamed’, and I

will build you a little house near mine and you will lack for nothing.”

Absentmindedly I put my small

hand into his large one, and our eyes filled with tears of joy.

Overjoyed, my schadchan

[match maker] and father-in-law returned home with me and with a cry of “Mazal

Tov” that echoed through the entire house approached his wife, my

mother-in-law, and said: “I congratulate you, Devorah’le. Mazal Tov, our eldest daughter Yetta’le,

has become a bride today and Hirsch’le is her betrothed for years to come.”

The sound of greeting and kisses

filled the house. Tears of joy streamed from everyone’s eyes, for the entire

family loved me and they all fell on my neck, kissed me and hugged me. The

young couple, the seventeen year old youth and the fourteen year old girl,

hugged each other[8] and cried,

but they did not kiss, ‘for they were ashamed…’[9]

My days as a melamed came

to an end, and the family members treated me as a master of the house from that

day on. One day the door opened suddenly and my little brother appeared. He had

walked from Slutsk to Pinsk to see his older brother who had almost reached his

“tachlith.” He brought with him the kisses of my widowed mother and

described her miserable situation. My brother and I were different – he was of

a courageous spirit, hated to complain and was always satisfied, contented with

his lot. He stayed with me for about ten days and then I sent him to our mother

in Slutsk with considerable help, according to what my situation at the time

enabled me.

*

The Days of Awe had come – the

most exciting days of the year for the Jews of the villages. The leaseholders

and innkeepers started the preparations for the journey in the month of Elul.

This journey was to take them to the cities and towns [stetalach] to

pray on Rosh Ha-Shana [the New Year] and Yom Kippur [the Day of

Atonement], that is to say, to hold proper services in a synagogue with a legal

quorum [a minimum of ten adult men].

They would take their gentile maids, who were acquainted with all the

Jewish customs, with them. They were

also equipped with a sufficient number of chicks and white chickens enabling

them to perform the custom of “Kapparot” for the entire family[10]. Traditional

pastries for these days were also prepared…. Indeed, it was a time when even

the fish in the rivers were terrified. In addition the country people would

take small sacks of ‘the choice products of the land’, the crops of the earth and

of the fruit of the trees, various types of beans and grits, oats and spelt, as

gifts for the home owners in the towns, who were to be their hosts for the

holidays.[11]

The town closest to our village

was Navliyah, which numbered about forty Jewish families. There were a few

affluent families, but most were impoverished and beggars; they waited all year

for the gifts their rural brethren would bring them for the Days of Awe. All

the rural Jews, the leaseholders and innkeepers, from the neighboring villages…with

their children and maids, their chicken and roosters, their sacks and

belongings would gather in the village of Womit on the shore of the pond, where

small boats awaited to lead them to the river that flowed to a spot near our

destination – the town of Navliyah.

The boats rowed on the lake, full

to capacity with young and old, men and woman, happy healthy youngsters, pretty

and shy maidens in full bloom. Christian maids, watching over the children,

were seated on sacks full of grain, foodstuffs and chicken coops carrying

roosters and chickens, future victims of “Kapparot” to atone for the

passengers’ sins. The boats sailed heavily on the pond towards the town to

celebrate the Days of Awe there.

Ha-Doar, 1934-5, no. 7, p

123

My First Sermon

As in the gathering of the exiles

the convoy of pilgrims descended from their boats to Navliyah, and the small

town was suddenly filled with a multitude of people. All the leaseholders and

innkeepers also brought their children’s teachers. Most of them were old and

feeble, men who had spent themselves as teachers [melamdim] in the

cities; their strength gone, they resorted to teaching in the villages where

they hoped to find a remedy for their ailments, sickness of the heart or

weakness of sight. Most of them were ignoramuses, all they knew was to read the

prayer book and hold the whip in hand to flog the “naughty” children, who

indulged in pure childhood mischief, refusing to listen to the teachers whom

they did not understand.

I went to see the local Rabbi, a young

man recently arrived from the Volozhin Yeshivah [religious academy]

equipped with an authorization. He understood Hebrew. When I came to the

synagogue he honored me, seated me at his side and introduced me to the leader

of the community who gave me the honor of delivering the sermon before the

prayer of “Kol Nidrei” [at the outset of the Yom Kippur Eve

prayers.]

For the first time in my life I

was to stand by the Holy Ark, wrapped in a Talith [prayer shawl] and

preach to an audience. True, I had already

tried to conduct a study of the Pentateuch with Abarbanel’s commentary in

public, and to explain a chapter of the prophets to my friends at the Mir Yeshivah,

but I never dreamt of preaching in a synagogue before Kol Nidrei. How

could anyone imagine that this sermon would be the first of thousands I would

deliver in my lifetime? While at the time my mind was occupied with the issues

concerning the mill and the harvesting of my father-in-law’s hay in the heart

of the famous marshes of Pinsk…

I gathered my courage and

ascended towards the Holy Ark. I felt my blood burning like a divine flame in

the heat of the large wax candles that lit the small synagogue. I remember that

a few minutes into the sermon the entire crowd was sobbing with me and terrible

shrieks were heard from the women’s gallery. I spoke for close to an hour about

the situation of our brethren in dark Russia, about our murky sources of

livelihood – the war between Turkey and Russia broke out that year [sic],[12] and I quoted

the verse: ‘The snorting of their horses was heard from Dan’ [Jeremiah 8,16),

and interpreted it in homiletically: the war had started from the river

“Donau”, Esau [Christendom] is fighting with his father-in-law Ishmael

[Islam]. I concluded with a prayer:

“Lord of the Universe, remove the goat [=Se’ir = the land of Esau, Edom] and

his father-in-law, ’for liberators shall march up to Zion!’”[13]

There was a drunken and evil man

in the audience, known as “Benjamin the Factor”. His livelihood was to supply

“Pan Lapitzki”, who was single all his life, with girls, farmers’ daughters,

and he served as the Pan’s [Polish landlord] matchmaker every single day. My

sermon about our “murky sources of livelihood” must have insulted him, and

immediately after the prayer of “Kol Nidrei”, he went to the Christian

priest and informed on me, reporting that I had cursed the government, the

Christian faith and first and foremost the Russian Czar…

Imagine the fear that seized the

Rabbi and the leader of the community when, on the next day, the town policeman

burst into the synagogue during the prayers and led the three of us to the

government official. He brought us into the official’s bureau, where we found

the priest and the informer, waiting for the three of us.

“Tell me, young Jew, what did you

speak about in the synagogue yesterday? For if what I was told is true, I shall

arrest you and send you to the district capital in chains.”

I answered him calmly: “Yes, Sir,

I spoke yesterday to a large audience, and they can all testify that what I

shall tell you is true. I talked about interest, saying it is a great sin, and

that my Jewish brethren should stop taking interest. They should work and

engage in various sustaining livelihoods. I spoke about the ‘factors’ that

disgrace their people. I hope that this sermon brings me the thanks and praise

of the government, rather than arrest and being led off in chains.”

The official looked at the

priest, gave me his hand and asked the three of us to forgive him for

interrupting our prayers on this holy day. The snitch left the bureau ‘his head

covered in mourning.’[14]

This event, that took place

during my first sermon, was ominous of my future fate – to be ready always to

confront the government officials, high and low, from without and our informers

and enemies from within, until I was exiled from the country, much to my

happiness and to the happiness of my family.

The last winter before my wedding

was also the last of my days as a melamed. I thought I had reached my

goal and found my tachlith (my purpose in life). From time to time I

sent money to support my widowed mother and orphaned brother. My brother was

happy for me. But deep down in my subconscious I felt I was not meant to be a

country man; that the meaning of my life was not to be found in the mill and

the fields, that my rightful place was in the city, and that my work should be

of a spiritual nature. I continued my study of the Talmud, persevered in

learning Hebrew grammar, and in reading our modern literature, and Russian

literature as well.

On the third day of the month of

Adar 5635 [March 10th, l875], I celebrated my wedding with the child bride,

Yetta Rubinstein, who was fifteen years old, while I was eighteen. The reader

nowadays may regard this marriage of young children, who know nothing of life,

appalling, a legacy of the middle ages. Yet he who reacts so knows nothing and

understands nothing of the pleasure of fathers as they look at forty- two

beautiful and fresh images of boys and girls, their descendants, grandchildren

and great grandchildren of the third and forth generations. He will not feel

what our predecessors felt, namely, that timely marriage leads to a beautiful

life, a life of morality and health, that leaves an eternal legacy for many

generations to come.

*

I am no longer a single man. God

has entrusted me with the responsibility for my family’s livelihood. I girded

my loins in leather and rose early in the morning to assist my father-in-law

with his work. I tried to engage in commerce as well, and was full of hope to soon

become my father-in-law’s partner in his fields and in the rest of his

endeavors as he had promised me.

One morning, as we were all

sitting at the table for breakfast, joyous, happy and eating heartily, the door

opened suddenly and the district policeman appeared bearing a government

document for Eliezer Rubinstein. It proclaimed that all his rights in the

fields and gardens belonging to Christian churches were ‘annulled and made

void’ from that day on, since the government had issued a new law prohibiting

Jews from buying or leasing landed property from Christians. The policeman

handed him the document and ordered him to sign it. My father-in-law was

terribly upset, his face became pale and he signed the order with a trembling

hand.

The policeman left and all of us

remained mute and dumbfound – staring at each other with horrific astonishment…

‘Tachlith” – practical

purpose and livelihood – had evaporated in thin air. The oil had spilled from

the pitcher, and what was to be done with an empty pitcher now?

My kind and generous

father-in-law made the utmost effort to gather his courage so as to console and

encourage us. He said that this evil

decree affected the public at large, it was directed against all the Jewish leasers

and tavern operators, and a general disaster is, as the proverb says, half a

consolation. But what is there to be done with the other half, for which there

is no consolation at all?

For a year I tried my best to

become a “wheeler dealer”, but I was not destined for commerce. I could not

adjust myself to petty trade and to the deceitful cheating talk it always

involved.

At that time my child-wife gave

birth to our eldest son – Chaim who was named for my father. The question of

our “tachlith” – our practical purpose in life – became even more acute.

Ha-Doar, vol. 14, 1934-5,

no. 9, p.158

Thanks to a Poem.

(A chapter from “My Life.”)

In time of trouble one never

knows ‘from where will… help come.’ In the midst of despair help suddenly comes

and restores you.

In my pitiful state I was saved

by one of the poems I had written while teaching in the country, though I had

never been a poet. My library consisted

of three books at the time: [the Hebrew grammar book] “Talmud Leshon

Ha-Ivri”, “Sefer Ha-Brith” [on basic sciences] and the Russian translation

of the Book of Isaiah. These three books supplied my spiritual nourishment.

Thank to the first I became a grammarian, the second introduced me to “The

Seven Wisdoms,” and the through the third I came to understand Russian, as did

the Maskilim in the early days of the Haskalah [the early

adherents of modern Jewish learning, Haskalah or Enlightenment] who

studied German with the aid of Mendelssohn’s[15]

translation of the Bible.

The poem mentioned was one of six

stanzas, which I wrote on the title page of Steinberg’s Russian translation [of

Isaiah]. In the first three stanzas I praised and lauded Steinberg for his

translation, and in the last three I cautioned him, saying he was not of the

same stature as Ben Menachem [Mendelssohn]. I had no idea whether there was any

poetry in that poem, but it did have some sensible ideas. I wrote it, left it

in the book, and forgot about it.

One day, one of my rural pupils

wished to enroll in the Hebrew School in town to complete his education. He

traveled to Pinsk, where the government-appointed Rabbi, Avraham Chaim

Rosenberg, had established a Hebrew School. The boy and his father reported to

the principal of the school; the youngster happened to be holding Steinberg’s

translation in his hand, for I had given it to him as a gift for his Bar

Mitzvah. Rabbi Rosenberg took the book in his hand and when he opened it

saw the poem on the title page. He immediately asked the boy’s father:

“Could you tell me who wrote this

poem?”

“ Yes, Rabbi, the poet was my

son’s teacher for three years.”

“Could I perhaps see him today?”

“He is in Pinsk now, at the

Katchinovsky Inn. He came to sell his merchandise, for he left teaching and is

trading in fish and hides, though with little success. If you wish to see him,

send for him and he shall come here,” answered the boy’s father.

That day as I was eating my lunch

at the inn, a man came forth and asked: “Is the son-in-law of Eliezer

Rubinstein from the village of Harinich here?” The innkeeper pointed to me, and

the man turned to me and said: “I have been sent by the Rabbi of the

congregation; he wishes you come with me to see him.”

All the people present were very

surprised: “What does the government-appointed Rabbi have to do with this young

villager?” for I was dressed in rural clothes.

I followed the man to the Rabbi

and found him in his school. For the first time in my life I saw a modern

school – a hall, large and broad, rows of benches with their desks. In the

center of the hall was a wooden black board. The teacher stood next to it,

chalk in hand, writing Hebrew words. He would call one of the pupils by name

and instruct him to read the words, add the proper vowels and explain them to

him. When the pupil erred he ordered him to return to his place and called upon

another pupil. The order and regime pleased me.

Rabbi Rosenberg handed his work

to another teacher and took me to his office. He was a tall man with a large

and handsome head, big black eyes and a round black beard. He looked at me,

observing my rural attire, the leather loincloth on my waist, and a slight

smile crossed his lips. He gave me his hand and asked that I sit next to him.

On the desk I saw Yehoshua

Steinberg’s translation. The book was open with my poem on the title page. I

was surprised – how did this book get here? The entire scene seemed like a

dream to me. He understood my confusion and did not keep me waiting. He then

asked me smilingly: “Is your name Zvi Hirsch Masliansky?”

“It is, Sir.”

“Did you write this poem?” he

asked again pointing at the title page.

“Obviously, my signature is on

it.”

“Kindly read it to me, young

man.”

I read the poem out loud,

emphasizing a certain place in a way that clarified my intention he had not

formerly understood.

He looked at my strange clothes

again, and addressed me affectionately: “And what are you doing? Where do you

live? What are your plans for the future?” I answered all his questions, from

the first to the last.

He got up, held me by the lapel,

and said: “Listen to me, young man, and take my advice. You are not destined

for country life, wheeling and dealing among the peasants. You should settle in

the city among your fellow Jews who will understand and cherish your talents,

and with time you will develop and become one of the great men of your nation. I advise you to become a Hebrew teacher.

Divide the day into hours, and spend each hour teaching in a different home.

But be aware of the melamdim and their Hadarim [traditional

teachers and schools] for they are in a very bad state. Teaching by the hours

will give you a status and provide you with a livelihood.”

He continued talking as he walked

me to the hall of the school, and said to me: “I shall be the first and give

you an hour or two of teaching in my school for the same salary I pay all the

other teachers.”

I looked at him with both

gratitude and amazement. “I do thank you, Sir, for your generous spirit, taking

interest in the fate of a desperate and lonely person like me. I am ready to do

anything you instruct me, but I don’t know if I can fulfill your wish as far as

teaching goes. This is the first time I have had the merit of seeing a modern

school. Till now all I saw were the old fashioned Hadarim devoid of any

order and regime.”

“This ‘lack’ can ‘be made good.’

I will spend a few days with you and instruct you in the modern methods of

teaching,” was his relaxed answer.

That very moment he brought me to

the best class in the school. The room was full of pupils and the great teacher

Feitelsohn stood next to the black board explaining the difference between the

definite particle and the interrogative particle in both meaning and vowels.

The teacher too looked at my clothes with surprise. The principal introduced me

to the teacher and asked him to allow me to take over for half an hour.

The teacher handed me the chalk;

On the black board I wrote several sentences that included the two articles

without vowels. The pupils added the vowels and seemed satisfied with my work.

The Rabbi then told me to ask the

pupils a grammatical question about verbs. I did as he wished, asked them about

the passive tense, and explained the answer to them. Rosenberg and Feigelsohn[16] approved of

my answer.

“And now, young man, return to

your home,” the Rabbi said as he bid me goodbye, “Cast off ‘the filthy

clothes…and… be clothed in [priestly] robes… and I will permit you to move

about among these attendants.’” [Zachariah 3; 4,7]

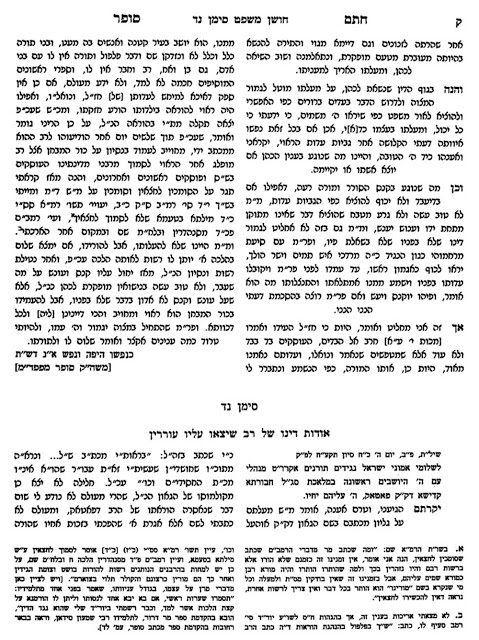

Ha-Doar, vol. 14, 1934-5,

no. 11, p. 194

Teacher and Preacher

(A Chapter from “My Life.”)

I succeeded in my first trial,

and immediately after the test was appointed as teacher in the school run by

the government-appointed Rabbi, Rabbi A. Rosenberg, in Pinsk.

With little delay I took my small

family, my sixteen-year-old wife and my half-year-old eldest child Chaim, and

brought them with me to Pinsk. I shouldered my burden – the burden of a Hebrew

teacher. I divided the day to twelve periods and spent each hour in a different

house with a different pupil.

I became known in the town thanks

to my teaching and when I would teach a chapter of the prophets [in the school]

with the windows open, men and woman, young and old, would gather in the yard

to listen. A few weeks later the wealthy families of Pinsk and Karlin, the

families of Luria, Zeitlin, Greenberg and Eisenberg invited me to teach their

children.[17]

And so I was burdened with work

every day from eight o’clock in the morning till eleven o’clock at night. I got

to see my only son only on Saturdays and Holidays. My kind father-in-law was

very disappointed that I could not spend any time talking to him when he came

to visit, for I was terribly busy.

With all that I devoted a few

hours a week to study science with Rabbi Rosenberg, the principal of the

school. Later in his life he wrote the ten-volume book “Otzar Ha-Shemot.”

I was not satisfied with teaching

the young. I felt I had sufficient talent to propagate my teaching and views

among adults as well. Much to my joy I became acquainted with the Rabbi of

Pinsk, the great and renowned Rabbi Elazer Moshe Ish Horovitz, one of the

greatest luminaries of his generation, a man of clear and broadminded ideas

about life in general and Jewish life in particular. The fanatic ultra-Orthodox

and the pious Hasidim were displeased with him and regarded him with suspicion.

But his vast knowledge of the Talmud and his righteous deeds protected him, and

they could do him no harm. At that time he came out publicly against various

customs [preceding the Day of Atonement] like “Kaparoth” and “Tashlich.”

He was especially irritated with a prayer [recited prior to blowing the Shofar

– ram’s horn – on the Days of Awe], which was full of weird named angels, and

ordered it to be eliminated from the prayer service in all the synagogues…

I became acquainted with this

wonderful Rabbi, and was considered as a member of his household and family. He

was a wonderful mathematician and excellent grammarian[18].

He spent many hours with me discussing Hebrew grammar and clarifying difficult

passages in the Bible using the methods of the modern commentators.

It was to him that I divulged my

desire to speak to [adult] audiences and he fulfilled it instantly. He sent for

the Gabai [synagogue director] of the Heckelman Schul and ordered

the synagogue to be opened every Friday night. I started delivering lectures on

the Psalms that very week for a large audience that filled the house

completely.

I recall these sacred evenings

with joy and glee, for they laid the foundation for my sixty-year-long carrier

as a preacher, addressing the people of Israel from the pulpit. I gave these

lectures for three years, performing this sacred duty for a hundred and fifty

evenings and reached chapter 50 of the Psalms. The audience was so enthusiastic

that a new institution was formed: “Masliansky’s Tehilim Sagen” [The

Masliansky Reciting of Psalms].

But there were some benighted

fanatics who started to persecute me, seeking evidence to support various

religious suspicions and allegations. Tudros the enthusiastic Hasid swore

solemnly that he had seen me carrying a handkerchief in my pocket on the

Sabbath and Moshe Itzel the bum watched me as I prayed and swore that I did not

rise for the prayer “Va-Yevarech David” [and David Blessed] and did not

spit during the prayer of Aleinu… But all this was to no avail – they

could not disgrace my name or humiliate me in the eyes of the people, who were

always ready to protect me in the face of any trouble, may it not befall us.

Once in my speech I reached the

verse in Psalm 31 [verse 7]: ‘I detest those who rely on empty folly, but I

trust in the Lord.’ I then poured my wrath on the superstitions, amulets,

incantations, demons and notes placed in graves addressed to the living and the

dead.

This speech affected all the

Hasidim, especially the “confedrazim”, those who have no Rabbi and

belong to all the courts. Their fanaticism is ‘unfathomable’ and their wrath is

as a ‘spider’s venom.’ They incited groups of little Hasidim, naughty and

mischievous, who ran after me in the streets ‘crying after me as a mob’ in

strange voices: “wil Gut ist einer, und weiterer keiner” [God is one and

there is none beside Him] – the words [of the famous Passover song] with which

I ended my speech. My adult persecutors sent a committee to the rich Hasidim

whose children I taught, telling them to banish me from their homes, but they

were unable to accomplish that, because the great Rabbi Ish Horowitz, learning

of their escapades, summoned the chief persecutor, Rabbi “Tudros the Hasid” and

reprimanded him and his friends. He ordered them to stop persecuting me, for he

knew me well and found no fault in me. The persecutors were frightened and left

me alone.

*****

[1] Grandfather of Joseph Masliansky.

[2] R. Chaim Leib Tikitinsky (1823-1899), Rabbi of Mir and head of its legendary yeshiva. (M.M.)

[3] Reference to the daily prayer service: ברוך אומר ועושה .(M.M.)

[4] Reference to T.B. Bava Metzia 8b. (M.M.)

[5] Earlier he was referring to his engagement when he said “it was as though his heart foretold that in two years time I would be his son-in-law”; the current statement factors in a year-long engagement after which he married his wife. (M.M.)

[6] “The Book of the Covenant“, an early 19th century attempt to harmonize natural sciences with Jewish religion and especially mysticism by Rabbi Pinchas Eliahu of Vilna, popular in ultra-Orthodox circles till this day.

[7] These three books indicate three ways contemporary Jews would follow in the quest for Haskalah, for broader horizons, beyond the confines of Yeshivah: Systematic study of Hebrew (especially Biblical Hebrew) and grammatically correct usage, leading to proper understanding of the Bible (as against the disorderly treatment of the language in the Rabbinical Responsa of the time); the study of a foreign language to gain access to European Culture (German in early Haskalah, and later, in Russia, Russian as well); the study of natural sciences.

[8] This behavior is quite liberal, as the prohibition against touching still applies even to engaged couples in ultra-Orthodox circles till this day.

[9] Reference to Gen. 2:25. (M.M.)

[10] According to this custom a person’s sins are supposedly transferred to a chicken, which is circled around his or her head. The chicken is later ritually slaughtered and the meat donated to charity. Nowadays this controversial ceremony is often substituted by a monetary donation, yet it is still performed in (mostly Ashkenazi) ultra-Orthodox circles

[11] The roots of the sociological structure described here are to be found in the Polish rule over these areas that lasted till the end of the 18th century. The Polish nobility owned vast tracts of land, comprised of rural areas and towns. To manage their rural estates they would hire managers (mostly Jews) who would pay a yearly advance for the operation of the estate or parts of it (such as a mill, an inn with a tavern). The leasers would charge the peasants for the services of the estate and keep the profit at the end of the year. The leaser (called ‘Yeshuvnik’ in Yiddish) and his family were often the only Jews for miles around. Hence the need to hire teachers for their children (as Masliansky was hired by the Rubinstein family) and to gather together for the High Holidays (The Days of Awe). The Russian authorities disapproved of this structure and during the 19th century tried, time and again, to have the Jews expelled from the villages. This effort culminated in the notorious “May Laws” of 1882; This expulsion and resulting lose of livelihood was one of main causes for the emigration to the United States and other countries, as were the actual pogroms that took place sporadically, mostly in southern Ukraine, following the murder of Czar Alexander II by revolutionaries in March 1881.

[12] The unrest in the Balkans started in the mid 1870s, but massive Russian intervention on behalf of the Slavic nations and a full scale war between Russia and Turkey did not occur till 1877. The events described here, on the other hand, relate to autumn l874, when Masliansky, born in l856, was eighteen years old. His wedding with Yetta Rubinstein took place in spring l875. When he wrote the memoirs he must have remembered quoting this biblical phrase and explaining it as referring to the tension between Russia and Turkey in the Balkans. This probably led him to assume that the war had already broken out at the time.

[13] The complete verse in Obadiah verse 21 reads: “For liberators shall march up on Mount Zion to wreak judgment on Mount Esau; and dominion shall be the Lord’s.” (JPS translation, l978) Masliansky was confident that his audience knew the end of the verse well and could understand his intention.

[14] A description of Haman in the book of Esther, 6,12.

[15] Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1789), German Jewish philosopher, considered as founder of the movement of Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah.)

[16]Unclear if it is Feigelsohn or Feitelsohn. (M.M.)

[17] The Hebrew writer, Yehuda Karni, then a child in Pinsk, gives a vivid description of the excitement and admiration the new teacher arose in the city, see (in Hebrew): N. Tamir-Mirsky, ed., Pinsk, a book of witness and memory of the Pinsk-Karlin community, vol. 2, Tel Aviv, Pinsk Organization in Israel, l966. We thank Prof. Zvi Gitelman of The University of Michigan for this information.

[18] Cf. the biographical elegy on him penned by his son in law, R. Boruch Halevi Epstein, נחל דמעה. (M.M.)