Mayim Hayyim, the Baal Shem Tov, and R. Meir the son of R. Jacob Emden

Sources contemporary to the Baal Shem Tov that attest to his deeds, or that even discuss him at all, are sparse. Although some secular sources, including tax records and other documents, have recently been unearthed by academic researchers, there is a paucity of Jewish texts. Most of the “historical” record regarding the Baal Shem Tov comes from a collection of stories, Shivhei Ha-Besht.[1] That work, however, was collected much later and is less reliable than others when assessing the Baal Shem Tov. [2] One important text regarding the Baal Shem Tov, however, appears in the Teshuvot Mayim Hayyim.

Mayim Hayyim was published in Zhitomer by Shapira press. The Shapira press is well-known for publishing hassidic works, and the press was originally in Slavita. As a result of dubious circumstances, the press moved to Zhitomer and in 1857 the Mayim Hayyim was published.[2a] While the publication of that book took place long after the Baal Shem Tov’s death in 1760, Mayim Hayyim consists of responsa both from the time of the Baal Shem Tov and later. Mayim Hayyim mainly consists of the responsa of R. Hayyim HaKohen Rapoport (1772-1839), was published by R. Hayyim’s son, R. Yaakov HaKohen Rapoport. R. Yaakov HaKohen Rapoport included material from other relatives as well (i.e., aside from his father, R. Hayyim). One such responsum is from R. Meir, son of R. Jacob Emden, who we shall return to later.

This undated responsum begins with a technical question regarding a lesion found in the lungs of an animal after shechitah. The slaughterer could not remove the lesion and took it to the local rabbi in Medzhybizh, a Rabbi Falk, who appeared to be unsure of the status of the animal. Based upon the remainder of the responsum, however, R. Falk eventually permitted the animal. It appears that some disagreed with the decision of R. Falk and thus sent the question to R. Meir to see if the local rabbi got it right. In an effort to ensure that R. Meir would get the whole story, it was recorded and signed by R. Mordechai, the ne’eman (literally, the trustee; but in this context, probably the secretary); the following appears after the question:

In our presence, the court signed below, our teacher, the aforementioned Mordecai, related all that is written above as testimony and then wrote all of this in his own handwriting and signed it with his very own signature. Therefore we have confirmed it and substantiated it as proper

Signed Israel BA”Sh [Ba’al Shem] of Tluste [this was the city the Baal Shem Tov lived prior to moving to Medzhybizh]

Signed Moshe Joseph Maggid Mesharim of Medzhybizh [3]

Thus, one of the three signatories was R. Israel Baal Shem Tov. The questioners then continue to flesh out their question as to whether or not Rabbi Falk paskened correctly. As Moshe Rosman notes, this question places the Baal Shem Tov as an important figure within Medzhybizh. That is, the Baal Shem Tov involved himself in this controversy, a controversy that may have resulted in the dismissal of their local rabbi. Furthermore, this episode illustrates how the Baal Shem Tov was important enough to be one of the three persons picked to sign on this letter. As Rosman states: “this incident presents a dimension of the Besht not usually emphasized by the interpreters of the hagiographic stories about him in Shivhei Ha-Beshet. It makes it difficult to portray him – as has often been done – as an unalloyed populist figure, alienated from the rabbinic or political establishment” (118).

Aside from the above value of the letter, there is the additional importance of how R. Meir treated the Baal Shem Tov, thus providing a contemporary account on how others viewed the Baal Shem Tov. Although the letter was from three people, R. Mordechai, R. Moshe Joseph and the Baal Shem Tov, R. Meir in his response only addresses himself to the Baal Shem Tov. Moreover, the honorifics R. Meir uses demonstrates that he surely held the Baal Shem Tov in the highest regard. R. Meir addressed the Baal Shem Tov as:

Champion in Yehuda and Israel! He who succeeds there at the small and the great. He provides balm and medicament to the persons without strength. He is great in Bavel and famous in Teveriah and has prevailed in all things. The great sage, the eminent rabbi, famous for his good name, our teacher Israel, may God protect and bless him. And all of his colleagues, all of them beloved rabbis, the great and eminent sage, our teacher Gershon, may God protect and bless him; and those who I don’t know [by name] I greet; may they all be granted the highest blessing.

As is apparent from the titles provided, “champion in Yehuda and Israel” and with the use of the terms “the great sage, the eminent rabbi” that R. Meir held the Baal Shem Tov in very high regard. Additionally, from both the Baal Shem Tov’s own use of “Baal Shem” to describe himself and R. Meir’s mention that the Baal Shem Tov “provides balm and medicament to persons without strength,” the term “Baal Shem” as used here refers to a medicine man. That is, aside from whatever else the Baal Shem Tov was known for, he was known for being a healer – thus Baal Shem means healer. This understanding is confirmed by tax records that refer to the Baal Shem Tov as a “Doctor.” From all this is should be apparent that the Baal Shem Tov was respected by his peers and was known outside of Medzhybizh while he was there.[4] Teshuvot Mayim Hayyim

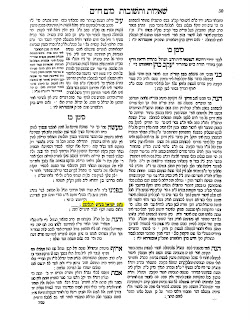

Teshuvot Mayim Hayyim

There is a question, however, regarding when the foregoing letter was written. Most place it sometime around 1744, but, at the latest, 1747. They do so based on the mention of “our teacher Gershon.” They understand that the Gershon referenced here is Avraham Gershon of Kutower, the Baal Shem Tov’s brother-in-law. As R. Gershon moved to Israel in 1747, and the letter mentions R. Gershon, it must have been while he was still in Medzhybizh.[5] Personally, I think that that conclusion assumes that R. Meir was intimately familiar with R. Gershon’s whereabouts. While there is no doubt that R. Meir heard of R. Gershon, it does not automatically follow that he was informed regarding when R. Gershon moved to Israel. It could very well be the letter was written after R. Gershon left for Israel and R. Meir then merely assumed that R. Gershon was still living in Medzhybizh – it is not as if there was an announcement in the Międzybórz Times or at OnlySimchas.com that R. Gershon had made Aliyah! Either way, this letter was written while the Baal Shem Tov was alive, and provides a virtually unimpeachable source for his participation in the community-at-large and about how others viewed him. I don’t think Rosman is exaggerating when he says that “[t]his responsum, then, would seem to be an excellent starting point for attempting to gauge the Besht’s position in his community and his relationship to the political and religious establishment” (119).

Aside from the above points that can be gleaned from this responsum, R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin, in an article that originally appeared in Sinai and has now been reprinted in the nice, new edition of his le-Ohr Halakhah uses this responsum for a different purpose. R. Zevin wants to disprove the notion that “the Hassidim and their Rebbes don’t care about studying the revealed Torah and thus they did not spend much time on studying talmud and poskim.” R. Zevin notes, as well, that this attitude towards Hassidim was prevalent right from the start of the Hassidic movement. That is, “even today, those who are not hassidim allege that the founder of the Hassidic movement, the Baal Shem Tov, was not a ben torah, heaven forbid.” R. Zevin totally rejects this notion as “false and incorrect.” As proof the Baal Shem Tov was indeed learned R. Zevin cites to the above responsum. R. Zevin explains:

In the Shu”t Mayim Hayyim from R. Hayyim Kohen Rapoport from Austria, printed there is a responsum from Medzhybizh regarding a lesion in the lung, from the Baal Shem Tov to the gaon R. Meir, the son of R. Jacob Emden, who was the chief rabbi in Constantine, and the response from the goan [R. Meir] to him [the Baal Shem Tov]. As is common knowledge, the Baal Shem Tov was not the Rabbi of Medzhybizh, even so the Baal Shem Tov is one of the signatories to the letter, singing it “Yisrael Baal Shem of Tluste” – “and the Maggid Mesharim of Medzhybizh.” [6] The response of R. Meir is a long one. R. Meir was not a hassid. It is important to note the honorifics R. Meir uses at the beginning of his response: “Champion in Yehuda and Israel! He who succeeds there at the small and the great. He provides balm and medicament to the persons without strength. He is great in Bavel and famous in Teveriah and has prevailed in all thins. The great sage, the eminent rabbi, famous for his good name, our teacher Israel, may God protect and bless him. And all of his colleagues, all of them beloved rabbis . . .” And would a goan [R. Meir] who is not a hassid uses such language on someone who is not a godal b’torah?

Therefore, R. Zevin, with this responsum, demonstrates that the notion that the Baal Shem Tov was not learned and not respected is utterly false.

Until now, we have been focusing on the Baal Shem Tov, but there is another important person in this responsum, the author – R. Meir (1717-1795)[7], the first born son of R. Jacob Emden.[8] R. Meir was the rabbi in Constantine in the Ukraine. R. Meir was highly respected in the area, as is demonstrated by this responsum. This is so, as you will recall, in that the purpose of the responsum was to settle a controversy in the town of Medzhybizh – a controversy between the local rabbi and some of the persons in the town. This was a serious controversy — indeed the petitioners describe it as “a fire burning in the community” — and, especially in light of R. Meir’s response, where he notes that the rabbi was wrong and if the rabbi refuses to admit that he is wrong, he is to be dealt with as a zakan maamrei as the rabbi, according to R. Meir, is denying a portion of the torah. This was no small matter. As the three persons picked R. Meir to adjudicate the matter, they must have respected him and thought that his answer, what ever it would be, would settle the issue.

Unfortunately, until now, we only had a tiny amount of written material from R. Meir, the bulk of which appears in Mayim Hayyim. Specifically, of the six extant responsa from R. Meir, four can be found in Mayim Hayyim. Now the reason they are included in Mayim Hayyim is because R. Meir is related to R. Hayyim HaKohen Rapoport.[9] What is shocking is that in his introduction to the Mayim Hayyim, R. Yaakov HaKohen Rapoport, publisher of the Mayim Hayyim, uses his relationship to R. Meir as the sole reason for publishing R. Meir’s responsa. That is, although the Mayim Hayyim was published by the Shapira hassidic publishing house in Zhitomer, and done so in the mid-19th century, R. Yaakov HaKohen Rapoport never mentions that he includes a responsum — the only one of its kind — from the Baal Shem Tov. Instead, the reason for the inclusion of the responsum is R. Meir.

As mentioned previously, today, Shmuel Dovid Friedman has attempted to fill the void of R. Meir’s works in publishing the first volume of R. Meir’s hiddushim. These hiddushim are on Mishnayot Seder Nashim and on the Rambam’s Mishneh Torah. The title of the book is taken from the above responsum. As R. Meir was referred to as “HaMeor HaGodol” thus the title of this new work is HaMeor HaGodol. See Meir Konstantine, HaMeor HaGodol, ed. R. Shmuel Dovid Friedman (Brooklyn, NY, 2007), [30], 352. [6]

While the publication of the Hiddushei Torah of R. Meir is indeed welcome, this particular work is plagued with numerous deficiencies. Firstand foremost is the problem with the manuscript itself. It does not appear that the Meor HaGodol was published from R. Meir’s actual manuscript. Instead, R. Meir’s manuscripts were copied over time by the Bick family and it is from these copies that the Meor HaGodol is comprised. Thus, there is no independent method of verifying that this material actually came from R. Meir. Aside from the manuscript, the introduction is rather bizarre. The introduction includes various stories about R. Meir, most of which focus on his relationship to hassidim. The bulk of the stories are then shown to be false, but only in the footnotes. So, the body of the text are the stories and then a careful reader will see that most of the stories likely never occurred. For instance, there is a story that R. Meir’s daughter — when R. Meir was sick and unbeknownst to him– sent a request to the Baal Shem Tov to ask him to heal R. Meir. The editors of Meor HaGodol, in note 49, then say it is hard to reconcile the story with the facts known about R. Meir. Or, another example is that the introduction includes a story that after R. Meir became a hassid — there is no evidence that he ever did so, but the story assumes so — his father, R. Jacob Emden, disowned R. Meir. Again, the editors, in note 59, state that “there are many difficulties with this story” and then proceed to enumerate them. Why a story for which there is no support would be included to begin with is left unexplained. Perhaps the reason is that the editors are unduly interested in demonstrating that R. Meir was a full hassid (indeed, the main chapter in the introduction is entitled “[R. Meir’s] Connection with the Baal Shem Tov”). It is particularly ironic that they present such shaky evidence in light of the fact the responsum in Mayim Hayyim from R. Meir is the only objective contemporaneous evidence of the Ba’al Shem from a Jewish source.

Moreover, the introduction seems to have missed and, in fact purposely left out, some material. Specifically, in note 3, the editors of HaMeor HaGodol note that R. Jacob Emden at some point added the name Yisrael. In the introduction they then attempt to understand what precipitated this change. They cite the following from R. Jacob Emden’s Hitavkut, (p. 112,a)

מבטן אמי קראני יעקב, אליו פי קראתי ורומם תחת לשוני, והוא יתברך שלחני בשמי קראני, וכעת הראני לקרוא שמי ישראל וכו’, ע”כ

“from birth I was called Yaakov, this is what I was called and my name elevated, and then God sent [a message] to me that I should be called in God’s name, and thus I will now be called Yisrael.”

Although we can see from that quote that R. Emden added his name, the introduction does not tell us exactly why. What is astounding is that the editors ought to know why R. Emden added his name. The reason is because the above quote from Sefer Hitavkut continues beyond the portion quoted and explains that the name Yisrael was added because it was a testament that R. Jacob Emden was correct in his battle with R. Jonathan Eybeschütz. Instead, the editors cut off the quote right before R. Emden explains precisely that. Therefore, I assume that the omission is because they would rather not bring up that R. Emden had a fight with R. Eybeschütz, or that R. Emden viewed himself as having been correct. It is worth noting that the Sefer Hitavkut is not the only place R. Emden offers his victory as the reason for the name change. Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter, on page 754 (n.11) of his dissertation about Rabbi Jacob Emden (Harvard, 1988), refers to a passage in Mitpachat Sefarim (p. 118 in the Lemberg, 1871 ed. and p. 171 in the most recent 1995 ed. – provided below) where R. Emden says “that after he battled with IS”H [R. J. Eybeschütz] a name was added” — a play on the verse in Genesis 32:24, 28. So it is incorrect to assert, as the editors of HaMeor HaGodol do, that “why and when R. Emden’s name was changed is unclear.” Rabbi Schacter also notes that Emden’s earliest reference “to himself as ‘Yaakov Yisrael’ is in a responsum SY [She’elat Yaavetz] II:24) dated February 22, 1765. In another responsum dated just six days later (SY II:144), Emden was addressed as ‘Yaakov Yisrael.’ For other references to this name, see SY II:25, 71, 72, 73, 112, [and] 146” (p. 754, n.11 – special thanks to Rabbi Schacter for his discussions with Menachem Butler about this aspect about Rabbi Jacob Emden).

Thus, in the editors’ effort to highlight the connection of R. Meir to hassidim, they downplay any opposition R. Meir’s father, R. Jacob Emden, had to hassidism (see n.59). They apparently were unaware (?) that an additional important statement from R. Jacob Emden has recently been published. (see here )

One final note. It is particularly disappointing today to find a sefer that does not contain an index. With technology as it is today, publishers easily should be able to provide a decent index to a book; it is quite surprising, then, that Meor HaGodol, does not contain an index.

Notes

[1] There are other sources as well, including letters. Many of the letters are highly controversial as to their authenticity. See Moshe Rosman, Founder of Hasidism: A Quest for the Historical Ba’al Shem Tov (University of California Press, 1996), 99-113, 119-126; Nahum Karlinsky, Historia SheKeneged (Jerusalem, 1998); and Immanuel Etkes, The Besht: Magician, Mystic and Leader (UPNE/Brandeis University Press, 2005), chapter six, “The Historicity of Shivhei Habesht,” 203-248, among many other sources.

[2] See Rosman, Founder of Hasidism, 143-155 and 162-8 (lending credence to some of the stories in Shivhei Ha-Besht based on governmental records), as well as his earlier article, “The History of a Historical Source: On the Editing of Shivhei Ha-Besht,” Zion 58 (1993): 175-214, and in his recently published monograph, Stories That Changed History: The Unique Career of Shivhei Ha-Besht (=The B.G. Rudolph Lectures in Judaic Studies, new series, 5) (Syracuse University Press, 2007), Rosman notes how through this text of some two hundred stories, one can “explore such themes as the Besht’s miraculous birth and childhood, his initiation into the mystical secrets, his revelations, his prayers, his dreams, his travels, his encounters with noblemen and priests, his contests with doctors, his attraction of various associates, and, most of all, the miracles, large and small, that he performs” (1). Rosman notes, as well, that over the past sixty years alone, “there have been five new Hebrew editions, some printed more than once; one Yiddish and two Hebrew reworkings; a German translation and critical edition, and an English translation printed four times. All this was in addition to various adaptations in fiction and in educational materials used by all types of Jewish schools, from Israeli secular to American Reform and Brooklyn Ultra-Orthodox” (24), and Rosman notes quite humorously how “Shivhei Ha-Besht has been analyzed as inspirational literature, political tract, holy writ, silly stories, historical source, and theological doctrine. It has entertained, inspired, embarrassed, inspired repentance, and formed the basis for doctoral dissertations. For nearly two hundred years it has been read with passion and diligence by people of many approaches and predilections. In search for the wellsprings of modern Jewish culture, it surely represents a unique source” (20).

[2a] For a discussion of the Shapira press see Ch. B. Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography in Poland (Tel Aviv, 1950), 104-09 (discussing the Slavita period) and 135 (discussing the Shapira press in Zhitomer). For what precipitated the move, see Saul Moiseyevich Ginsburg, The Drama of Slavuta, trans. by Ephraim H. Prombaum (Lanham, Maryland, 1991).

[3] I have essentially used Rosman’s translation of this responsum.

[4] See Rosman, Founder of Hasidism, at 168.

[5] Dinur, B’Mifaneh HaDorot, vol. 1, pp. 205-6, cited in Rosman, Founder of Hasidism, 119 n.29.

[6] This is actually incorrect. The Baal Shem Tov does not sign himself as the Maggid of Medzhybizh, rather the final signatory, R. Moshe Yosef signs himself as the Maggid.

[7] 1795 is the death date given in HaMeor HaGadol, (there are no page numbers provided in the introduction thus I will use the footnote numbers to attempt to give a rough citation) at n.60. The source given is “a letter from R. Mordechai Blechman z”l the chief rabbi of Constantine to R. Hayyim Bick the chief rabbi of Medzhybizh.” The editors of HaMeor HaGodol, however, fail to provide where this source is located, i.e. is it in their possession, is it in some library or perhaps somewhere else. Moreover, they do not provide the context of the letter – was R. Meir’s death date mentioned in passing or was that the focus of the letter. Nor do they mention how R. Blechman knows this date. Did he pull it off of R. Meir’s tombstone or was it simply a legend? This sort of lack of information plagues the entire introduction of the Meor HaGodol.

This same death date, however, is given by Abraham Bick, Rebi Yaakov Emden (Jerusalem, 1974), 17, 182. Bick doesn’t either provide a source for this date. See also id. at 17-8, citing to where R. Jacob Emden and others quote R. Meir. About Bick’s 1974 biography, Schacter writes in his dissertation, that this work “is uncritical, incomplete and simply sloppy. it is barely more useful than an earlier historical novel in yiddish about emden by the general author with the same title published in New York, 1946. In general, all of Bick’s work is shoddy and irresponsible and cannot be taken seriously.” See Jacob J. Schacter, “Rabbi Jacob Emden: Life and Works,” (PhD dissertation, Harvard, 1988), 17.

The editors of HaMeor HaGodol explain that most of the biographical information on R. Meir comes from Kitvei HaGeonim (Pietrokov, 1928), 127-30, n.3. Additionally, R. Meir is mentioned a few times in his father’s autobiography, Megilat Sefer, Kahana ed., (Warsaw, 1896), 104 and 110. R. Jacob Emden mentions that he was unable to attend R. Meir’s wedding in 1732 even as his wife attended, though as Schacter notes in his dissertation, R. Emden had “travel[ed] to Amsterdam during this period” (152, n. 126).

[8] R. Meir was related to R. Rapoport through the marriage of R. Meir’s daughter to R. Hayyim HaKohen Rapoport’s grandson, Dov Bear. See R. Jonathan Eybeschütz, Luchot Edut (Altona, 1755), 62a. Additionally, R. Meir was the brother-in-law of R. Shlomo Chelm, author of the Merkevet HaMishna. One of the responsum in Mayim Hayyim, no. 28, from R. Meir is to R. Shlomo.

[9] In fact, this is the only reason why the responsum that includes the mention of the Ba’al Shem Tov appears in Mayim Hayyim. As mentioned above, when the Mayim Hayyim was published, it was done so not by R. Hayyim HaKohen Rapoport, the author of the bulk of the teshuvot, but instead by his son R. Yaakov. R. Hayyim had died prior to publishing his own works. Thus, R. Yaakov decided to include not only his father’s responsa but those from other relatives, as well. Thus, the Mayim Hayyim contains two title pages. After the first title page, the approbations that R. Hayyim received for his responsa are included (one additional later approbation is included but the main are addressed to R. Hayyim). R. Yaakov then included a second title page after which two additional approbations are included. These approbations were collected by R. Yaakov and mention not only R. Hayyim’s responsa but the inclusion of other luminaries including R. Meir. The second title page is used a division between the two types of approbations, those directed at R. Hayyim and those at the book Mayim Hayyim. It is worthwhile noting that in the electronic editions they have removed the second title page. For instance, www.hebrewbooks.org only includes the first. This is but one example of the need to actually obtain a hard copy of a book and not solely rely on such databases. See Anthony Grafton, “Future Reading, Digitization and its Discontents,” The New Yorker (Nov. 5, 2007) and his New Yorker web-supplement, “Adventures in Wonderland,” for other limitations of digitization.