Tevie Kagan: The Enigmatic R. David Lida Part II

by Tevie Kagan

R. Shmuel David Luzzato (Shadal) in his Mevo l’Machzor Beni Roma, discusses Kallir and the history of piyyutim at length.[1] “If you will ask who authored the first piyyut and who followed them, I will answer that the first is Yanni or Yinai, and the second is R. Eliezer Berebi Kalir. The product of both is apparent to all in the Haggadah as the piyyut “Az Rov Nissim” is from Yanni . . . and the piyyut “Ometz Gevoroteha” is from R. Eliezer berbi Kallir . . .” Interestingly, “regarding Yanni a nasty rumor has been spread (Zunz found it in a manuscript commentary to the Mahzor), however, anyone who hears it will laugh, . . . [and the rumor is] that Yanni became jealous of his student R. Eliezer and [Yanni] put a scorpion in [Eliezer Kallir’s] shoe and the scorpion killed Kallir.” Shadal, however, dismisses this rumor in light of the fact that Yanni’s piyyutim are still said, especially the one mentioned above during Pesach. Shadal argues that if Yanni was a murderer then there is no way Yanni’s piyyutim would be so popular. Additionally, Rabbenu Gershom mentions Yanni and uses honorific terms, something Rabbenu Gershom would not have done if the rumor is true.

Shadal then turns to the details of R. Eliezer Kallir’s biography. “In many places R. Eliezer signs his name as ‘R. Eliezer beribi Kallir from Kiryat Sefer.’ Many of the early ones believed that this indicated Kallir was from the biblical town of Kiryat Sefer, and many thought that Kallir was a tanna, either R. Eliezer the son of Simon … or R. Eliezer ben Arakh, both of these opinions are recorded in the Sefer HaYuchsin.” Shadal, however shows that it is highly unlikely that R. Eliezer Kallir was a tanna or that he was from the biblical town of Kiryat Sefer. Instead, Shadal quotes the opinion of R. Moshe Landau (grandson of the Noda Be-Yehuda) in his commentary to the Arukh, Maarkhe Lashon. [2]According to Landau Kallir is a reference to the Sardinian city Cagliari. Shadal disagrees with Landau. In the end, after citing other opinions, including identifying Kallir with an Italian city, Pumadisa in Babylon, and Sippara also in Babylon, and to those it should be added, Bari, Ostia, “Civitas Portas, the former port of Rome (Derenbourg); Constantinople; Civita di Penna in the Abruzzi; . . . Normandy, Speyer in Germany . . . Lettere in Souther Italy, . . . Antioch and Hama in Syria . . . Kallirrhoe in Palestine . .. [and finally] Tiberias.” E.J. p. 744. As should be apparent, there is no consensus on where Kallir was from.

Turning to his name – Kallir – the starting place is R. Nathan and his Arukh. He explains that Kallir, means cake (indeed in Greek kalura means cake). And, Kallir was called “cake” because “he ate a cake that had written on a kemiah (amulet) and, as a result, he became smart.” Arukh erekh klr. The idea to feed children cake with inscriptions is a well documented one. R. Eliezer from Worms, the author of the Rokekh records the custom to feed children cakes with the verses from Isaiah 50:4, id.50:5, and Ezekiel 3:3. The children would eat these when they were indoctrinated into Torah study on Shavout. [3]Of course, as noted above, some view the name Kallir as an indication of where Kallir was from. Indeed, many, including Shadal did not swallow (if I may) the Arukh’s interpretation of Kallir.

Again, as we have seen there is a bit of debate when it comes to Kallir, one of the more interesting debates regards which piyyutim can be attributed to him. While in many Kallir provides his name in an acrostic, according to R. Shelomo Yehuda Rapoport (Shir) one can also attribute those piyyutim that there is a gematria that equals some permutation of Kallir’s name. That is, Kallir sometimes signed his name Eliezer haKallir, Eliezer beribi Kallir, Eliezer Kallir me-Kiryat Sefer, and a combination of any of these. Thus, according to Shir, if in the first line equaled any of these Kallir was the author.

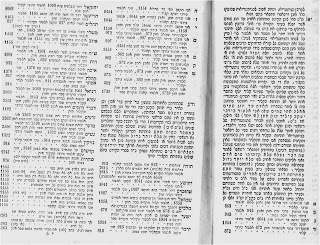

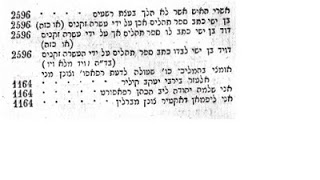

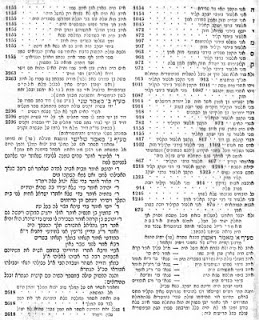

R. Efraim Mehlsack, however, took issue with Shir’s use of gematria. Specifically, Mehlsack wrote Sefer ha-Ravyah, Ofen, 1837, against Shir. Mehlsack was a prolific author, he supposedly authored some 72 seforim, but the only published sefer was this one. But before we get into the details regarding Mehlsack we need to discuss his critique of Shir. Mehlsack went to town on Shir and showed that using the gematria for the first line of a book, Mehlsack could make Kallir the author of just about every important Jewish book. Mehlsack goes through Tanakh and uses the first verse of each book to equal some form of Kallir’s name. For example, the first verse in Berashit equals 913 which equals “meni ha-katan Eliezer Kallir.” The first verse in Joshua equals 1041 which equals “ha-katon Eliezer beribi Kallir.” Mehlsack doesn’t stop with Tanakh, he then moves to Mishna noting that the first mishna in Berkhot is 2362 which equals “ani Eliezer berbi Ya’akov ha-Kallir mi-Kiryat Sefer yezkeh be-tov amen.” As a final shot at Shir, Mehlsack has the gematria of I am Shelmo Yehuda Rapoport = 1164 to Eliezer beRebi Yaakov Kallir =1164. Indeed, Mehlsack was not content to provide some 40 odd examples, he had even more and as a result of already printing the pages, the Sefer Ravyah is an interesting bibliographical oddity in that these gematrias appear on page 18 and then continue. Well Mehlsack includes an alternative page 18 in the back which has more examples of these gematrias. Thus, the book goes until page 32 and then there is another page 18. Both versions appear below.

Turning now to Mehlsack. As I mentioned Mehlsack supposedly authored 72 books. We know of 34 titles from that list.[4] Although most of those works have been lost, there are a few, around five, that are available in manuscript. In Boaz Hass’s recent book on the history of the Zohar, he mentions Mehlsack’s translation of the Zohar (Scholem also discusses this work). One of the works lost, is a work permitting one to travel via train on Shabbat. The introduction of this work has been published (in part) and appears below. Additionally, Sefer Ravyah was not Mehlsack’s only attack on Rapoport, Mehlsack attacked Rapoport in a few of his works, and some of his critiques were published in Bikkurei Ha-Ittim.

few, around five, that are available in manuscript. In Boaz Hass’s recent book on the history of the Zohar, he mentions Mehlsack’s translation of the Zohar (Scholem also discusses this work). One of the works lost, is a work permitting one to travel via train on Shabbat. The introduction of this work has been published (in part) and appears below. Additionally, Sefer Ravyah was not Mehlsack’s only attack on Rapoport, Mehlsack attacked Rapoport in a few of his works, and some of his critiques were published in Bikkurei Ha-Ittim.

Returning to Kallir, it goes without saying that Kallir’s piyyutim were controversial. Most famously, the Ibn Ezra complained about them and offered that one should refrain from saying Kallir’s piyyutim. Ibn Ezra’s critique is discussed by R. Eliezer Fleckels, who defends Kallir, and Heidenheim thought it important enough to include this lengthy responsum in Heidenheim’s edition of the Machzor.[For more on the Ibn Ezra see צבי מלאכי “אברהם אבן-עזרא נגד אלעזר הקליר – ביקורת בראי הדורות” פלס (תשם) 273-296)

Bibliography on R. Eliezer Kallir (provided by a kind reader of the blog.)אלבוגן, התפלה בישראל בהתפתחותה ההסטורית, 233 – 239יוסף זליגר, “לתולדות הפיוט והפיטנים (ר’ אלעזר קליר)”, כתבי הרב ד“ר יוסף זליגר, לאה זליגר מו”ל, ירושלים תרצ, צז – קבשלמה דוד לוצאטו, אגרות שד“ל א, 464 ואילך—, הליכות קדם, גבריאל פאלק, אמסטרדם תרז, מחלקה שניה, 56 – 64.צבי מלאכי, “הפייטן אלעזר הקליר – לחקר שמו ומקומו”, באורח מדע: פרקים בתרבות ישראל מוגים לאהרן מירסקי במלאות לו שבעים שנה, צבי מלאכי, מכון הברמן למחקרי ספרות, לוד תשמו, 539 – 543אהרן מרקוס, ברזילי: מסה בתולדות הלשון העברית, ירושלים: מוסד הרב קוק תשמג, 346עזרא פליישר, תרביץ נ, 282 – 302 —, “לפתרון שאלת זמנו ומקום פעילותו של ר’ אלעזר בירבי קיליר”, תרביץ נד ג, ניסן – סיון תשמה, 383 – 427שלמה יהודה ראפאפארט, תולדות גדולי ישראל, 24 – 55יעקב שור, ספר העתים, 364 – 365 בנועם שיח: פרקים מתולדות ספרותנו, מכון הברמן למחקרי ספרות, לוד תשמג, 114 – 156 המעין טז א, תשרי תשלו, 3 – 14. המשך: ב, טבת תשלו, 32 – 52.

[1] Mevo leMachzor Beni Roma, Habermann ed. Jerusalem[2] For more on this commentary see S. Brisman, History & Guide to Judaic Dictionaries & Concordances, KTAV Publishing House, Inc. 2000, pp. 19-20.[3] For more on this custom see Assaf, Mekorot le-Tolodot ha-Hinukh be-Yisrael, Jerusalem 2002, pp. 80-1 n.9 and the sources cited therein. See also, E. Kanarfogel, Peering through the Lattices, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 2000 pp. 140-41 and the notes therein (discussing the ceremony generally); id.p. 237 n.47 (discussing some of the halakhik issues with this custom including the “issue” of “excret[ing] these verses”)[4] See G. Kressel, “Kitvei Mehlsack,” Kiryat Sefer 17, pp. 87-96.

David Glasner, an economist at the Federal Trade Commission, is a great-grandson of Rabbi Moshe Shmuel Glasner, the topic of his recent post, “The Saga of Publishing the Works of Rabbi Moshe Shmuel Glasner: The Issue of Inclusion of Zionism and Rav Kook,” at the Seforim blog.

This is his second contribution to the Seforim blog.

Adderabbi wrote to inquire whether my father was his grandfather’s friend in Baltimore. The answer is yes. My parents were very fond of your grandparents, and it was a great loss to them when your grandfather passed away suddenly a number of years ago and again when your grandmother passed away not too long after that. My older brother is the one from State College, PA. And my question to you is whether Eugene is your father or your uncle.

About the fate of my unpublished introduction, I hope to revise it and submit it to a suitable Hebrew language journal for publication. I think we’ll just have to wait and see whether it ever gets posted on this blog.

I thank Yehudah Mirsky for his multiple contributions. After his first mention of Rav Amital, I immediately thought of the achingly beautiful tribute he wrote in memory of his Rebbi, R. Haim Yehudah Levi, a grandson of the Dor Revi’i. Rav Amital delivered a hesped at my father’s burial in Jerusalem just over three years ago and mentioned the closeness that he felt to the family of the Dor Revi’i and how important he believed it is to preserve the legacy of morality and justice and honesty that the Dor Rev’i represented. It is also a pleasure to renew, even if only via cyberspace, my acquaintance with Yehudah, with whom my wife and I enjoyably spent many a Friday evening in the splendid company of my illustrious cousins Menahem and Ruth Schmelzer, their family and friends.

Anonymous (02.16.08 – 6:47 pm) charged me with complicity in suppressing the truth about my great-grandfather. Well, obviously there were multiple values at stake and the outcome represented some sort of balancing of those not entirely congruent values. Did I clarify that for you? I also thank anonymous (2:17.08 – 12:31 am) for what I understood to be a sympathetic comment about the difficulty of the situation in which I found myself.

Thanbo asked about the new edition of Dor Revi’i published about five years ago. I had no role in that enterprise. I can’t really comment about its physical dimensions or about future editions.

Zalman Alpert is clearly more conversant with Haredi demographic trends than I, but I will just add another interesting tidbit, which is that although Hassidus was making inroads in Hungary before WWII, it was only after WWII that the great majority of Haredi Hungarian Jewry attached themselves to one or the other of the Hassidic dynasties. The Klausenburger Rebbe, for example, obviously had many thousands more Hasidim after the war than he ever did before the war. In my own family, my maternal aunt and uncle from fine upstanding Oberlanderish extraction became staunch Belzer Hasidim after the war. Hungarians I think did come to predominate after the war in a number of sects that, like Belz, were not mostly Hungarian before the war. While there may be something in Zalman Alpert’s conjecture that being from a separatist Hungarian background helped preserve the Dor Revi’i’s standing among the Haredim, I am not inclined to think that it mattered very much. His Zionism was of such an outspoken nature that he was reviled in his own time as a turncoat and a traitor to his roots and his upbringing. Indeed, the animosity toward him resulted from an existential feeling that his Zionism was not a mistake but a kind of treachery. By the way, there are at least two places in which he explicitly addresses the question of separation. First in a teshuvah (shut dor revi’i, 2:86, dated seder tetzaveh 5657) defending separation against the criticism of separation made by the rishon l’tzion, Rabbi Yakov Shaul Elisher (interestingly the only (?) other defense of separation against this criticism was by my great-great-grandfather, R. Amram Blum in shut beit she’arim). This teshuvah is largely a rhetorical recitation of the outrages perpetrated by the Neologs in trying to force the Orthodox to yield to their state-sanctioned domination, and a plea to Rabbi Elisher not to be duped by the misrepresentations made by the Neologs. Almost 25 years later, the Dor Revi’i revisited the question of separation in his essay on Zionism (my English translation is posted on http://www.dorrevii.org/). In the latter essay, he took a more analytical approach to the question of separation, arguing that separation was defensible only on the grounds that the hidden agenda of the Neologs was to promote assimilation. Since Zionism was aimed at maintaining the Jewish national identity, the precedent of separation was therefore irrelevant to the question whether cooperation by the Orthodox with irreligious Zionists was justified. He further accused the Haredim of his day of competing with the Neologs in unedifying displays of Hungarian patriotism (e.g., describing themselves as Magyars of the Mosaic faith), a withering condemnation that surely did not endear him to his Haredi antagonists. About Professor Moshe Carmilly-Weinberger, I didn’t forget him, but I wasn’t writing a comprehensive religious history of Klausenburg, so, with all due respect to him, I didn’t feel that he was particularly relevant to the story I was telling. But having warmed to the subject, I will note that in one of his writings (or perhaps a talk that someone once told me about) he described his boyhood experience of being taken by his father to see the Dor Revi’i and the lasting impression that the encounter made on his memory. I don’t have any statistics at my fingertips, but I would be really surprised if the Neolog community was much more than a tenth the size of the Orthodox community in Klausenburg.

Anonymous (2.17.08 – 12:01 pm) asks about the friendship between Rav Glasner and R. Shaul Brach. This relationship was certainly between my grandfather, R. Akiva (about whom more will be said below) and R. Brach. I have no specific information about their relationship except that R. Brach was one of a number of highly regarded Haredi rabbis from whom my grandfather obtained glowing haskamot for his first book, Dor Dorim. The choice of the title (as well as, if one reads carefully, the hashqafic discussion in the introduction) and the choice of rabbis to write haskamot show how delicate a balance my grandfather was trying to maintain between loyalty to his father and achieving a reconciliation with his father’s enemies.

To Yaakov R., without going into any details, I can assure you that the cast of characters involved in the story I told was international. I also did not mean, and am sorry if anyone thinks that I tried, to “bash” Haredim or to satirize them. If they appear in a less than favorable light, it is not because they are bad people, but because they face social pressures to conform that are very difficult to withstand.

Anonymous (2.19.08 – 7:13 am) wants to know if there is unpublished material of the Dor Revi’i. Yes, unfortunately there is a lot that has never been published, and, even more unfortunately, no one seems to know what has become of it. At the end of his introduction to Hulin, he mentions that he hoped to arrange and publish his hidushim on “rov sugyot ha-shas” as well as many hundreds of teshuvot and divrei aggada which he had in manuscript. He presumably took most of that with him to Palestine in 1923. I recall reading in some source, whose identity, to my great consternation, I can no longer recall, that his unpublished manuscripts were held by Mosad ha-Rav Kook. When I contacted someone in the mosad about those manuscripts, I was told that they had no knowledge of their existence and that in any case all extant manuscripts in Israel had been photographed and were held in the microfilm collection of the Jewish National Library. The only holdings of microfiche of works of my great-grandfather held by the JNL are of the 200 or so teshuvot that somehow came to light in the mid-1970s that were published in two volumes of shut dor revi’i.

To Zalman Alpert, since you mention the story about R. Koppel Reich, I will just note that Koppel Reich’s son married a daughter (possibly the oldest) of the Dor Revi’i. They died in the Holocaust and left no survivors. About my grandfather’s speech at the Knessiah Gedolah in 1937 at Marienbad, my father accompanied his father on that occasion (he was then 19). He told me that his father decided to join Agudah at that time, because at that meeting the Agudah dropped its opposition to the creation of Jewish state in Palestine. According to my father, that was the matir for his father to join Agudah, which contributed to his own fence-mending and furthered his (ultimately futile) desire to re-unite the Orthodox community in Klausenburg. As I pointed about above, to achieve that goal, my grandfather always sought to mend fences with his father’s enemies (though certain well known relatives of my dear and learned friend Mechy Frankel were utterly implacable), and he even made every effort to maintain cordial relations with Rabbi Halberstam. I have heard, though I have been unable to confirm, that at the wedding of one of his daughters he was mekhabeid Rabbi Halberstam with a brakhah at the hupa. At any rate, it was the change of position by Agudah that led my grandfather to join Agudah and make the speech from which you quoted. I was once told by my grandmother’s brother that in Mizrahi circles his speech was viewed as a betrayal and resulted in his not being offered a suitable rabbinical post in Israel after 1948 when he might have been receptive to such an offer. In the end, however, the resolution adopted in Marienbad in 1937 (which also precipitated the creation of Neturei Karta in outraged protest) reflecting the position of the majority in attendance at Marienbad was effectively negated by the determined opposition of Rabbis A. Kotler and E. Wasserman with the enthusiastic support of the Hungarian anti-Zionists. I would add as a postscript that b’sof yamav, my grandfather made totally clear his true convictions when in 1956 only a few months before his petirah (29 tishri 5717) he wrote a teshuvah ruling that one is obligated to say Hallel on Yom ha-Atzmaut. My translation of that teshuvah is available on the Dor Revi’i website (http://www.dorrevii.org/).

To Lawrence Kaplan, you are probably right to be surprised. While I knew that Rabbi Kook was not a hero to Haredim and his books were not recommended, I did not imagine that the mere mention of his name in connection with another person would suffice to pahsel the other person as well. I also thought that the fact that Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach and Rabbi Elyashiv were his students and always remained devoted to him and his memory provided a certain amount of cover for him. Nor did I imagine that there was anyone who knew about the Dor Revi’i that did not also know that he was a Zionist. Live and learn.

I’m not sure why the esteemed and learned Dr. Frankel seems to have a problem with my dating of events in Klausenburg near the time of the Dor Revi’i’s departure. Those dates are well established in publicly available sources. He is correct to say that the Klausenburg secessionists were not the first Sephardic community to be formed in Hungary, but the existence of earlier Sephardic communities elsewhere in the vicinity does nothing to establish that the Klausenburg chapter predated 1921. Whatever it was that happened in 1873 (and Dr. Frankel provides no details or documentation to support his assertion about that date), it was evidently short lived. If Dr. Frankel believes otherwise, I would most respectfully invite him to provide any information that he might have about the leadership (rabbinical or otherwise) or the makeup of the community in the nearly five decades between 1873 and 1921. It is well-established that there was a Neolog breakaway in Klausenburg in the 1880s (one oft-cited reason for which was my great-grandfather’s affection for Hassidim and Hassidut). That breakaway, at least, did last until the Holocaust. And I thank my friend for his nostalgic (to me, at any rate) references to bygone times when we were neighbors in geographic as well as hashqafic space.

Comments by Steve Brizel and Michoel Halberstam suggest that my posting misled them into thinking that something that the Dor Revi’i wrote was suppressed. That is not, repeat not, the case. What I withhold, out of consideration for the feelings of those who would have been embarrassed, offended, or would have felt otherwise aggrieved, by seeing such a reference in the newly published volume of his works was my introduction about the life and character of the Dor Revi’i, which mentioned both his Zionism and his close friendship with Rabbi Kook. I would just like everyone to be clear on those facts.