Rabbi David Hoffmann, ZL

By Eliezer M. Lipschuetz

Introduction, Translation, and Notes by David S. Zinberg

__________

The story of his life – the properly developed life of a Torah scholar – was not eventful. His birthplace, Jewish Hungary, was unique; she experienced a late spiritual awakening, and for generations lacked any great Torah scholar or spiritual leader. But from the very moment her Torah began to shine, she was granted a short-lived daybreak full of light and vitality. She influenced much of the Diaspora, in many fields of study, both within and beyond the Jewish domain. He was born in the community of Verbó (Nitra province) in Hungary,

[2] on 1 Kislev 5604 (November 24, 1843). His father was a local religious arbitrator [

dayan]. He received the standard c

heder education, though it included personal attention and supervision. From the time of Rabbi Moses Sofer, Hungary was blessed with yeshivot whose curricula differed from those of Lithuanian yeshivot. Even as a young man, he earned a reputation as a Talmudic prodigy [

ilui]. He studied at the yeshivot of Verbó and Pupa

[3] and later at the yeshiva of that generation’s most prominent rabbi [

gadol ha-dor], Rabbi Moses Schick, in Sankta Georgen

[4] near Pressburg,

[5] where he was his teacher’s absolute favorite.

Around this time, a notable event took place in Hungary: Rabbi Esriel Hildesheimer, a German Torah scholar who served as rabbi of Eisenstadt, founded a yeshiva for both Torah and secular studies during a period of extremist agitation. The two opposing camps had separated angrily, and the Jewish community was split in two. At this inopportune time, the life of this yeshiva was cut short, as was the residence of its founder in Eisenstadt, due to the shrill protests of the ultra-conservative camp. It was feared that an extremist war would be waged against Rabbi Hildesheimer or, even worse, that he would mount a counter-offensive against the Torah leadership. Purity and Torah were in danger of becoming apostasy; alas, such is the power of communal dissension. He escaped the place of expected misfortune and returned to his native Germany where he became a rabbi and innovative leader of the Orthodox community.

Rabbi Hoffmann was Rabbi Hildesheimer’s student at his yeshiva in Eisenstadt and when his teacher departed, he did as well, arriving at the Pressburg Yeshiva, the central yeshiva in Hungary. Later, he studied at the University of Vienna and from there moved to Germany where he taught at the preparatory school of the Jewish Teachers Institute at Höchberg, near Würzburg. There, he was a colleague of Rabbi Seligman Baer Bamberger, another German Orthodox rabbi, whose goal was to safeguard the light of Torah within daily life. Rabbi Bamberger was a old-school scholar; he was mild mannered in ideological controversies and viewed the Jewish community as single entity which should not easily be split.

In 1875 [

sic], Rabbi Hoffmann composed a dissertation,

A Biography of Mar Shmuel,

[6] and received a doctorate from the University of Tübingen.

[7] He then married a woman from a prominent family, who survived him, and was invited by Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch to teach at the high school

he had founded. This was the first modern school for Orthodox students. Rabbi Hirsch fought the battle for Torah with the weapons of modern Enlightenment. He strove to consciously combine Enlightenment and Jewish ideology, but he viewed himself as a wartime general, and was inclined to separate and confine the Orthodox community. Rabbi Hoffmann served for a number of years as a teacher in Rabbi Hirsch’s school, and was close to him. After only a short time, Rabbi Hoffmann became closely connected with three of the spiritual leaders of the new Orthodox movement in Germany. At that time, Orthodox Judaism was aroused to defend itself, to establish relations with the new culture, and to create a Torah lifestyle within a foreign society. These three great leaders, though they had different personalities and goals, stood at the vanguard of the movement, to organize and dig in the troops. Rabbi Seligman Baer Bamberger continued to support earlier developments, disapproved of separatism, and strove to preserve an ideal of perfection untarnished by current fads. Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch understood the full extent of the battle; he felt obligated to pursue total, uncompromising Enlightenment, and a Judaism that included full intellectual awareness. He established an ideological basis for Judaism, founded on intellect, and created a rationalist system based on principles of faith. He considered his age one of creating boundaries and he preferred separatism. Rabbi Esriel Hildesheimer believed that his mission was to advance the scientific understanding of Judaism and to preserve its image in the eyes of science. He desired that Torah should never be forgotten in Israel, and although he too believed at the time in the need for separation, he maintained his sense of responsibility towards the wider community. The leadership of German Orthodoxy succeeded, then and forever, to create the type of Jew who combines within himself involvement in daily life [

derekh eretz] and the fear of God, and to create a modern Orthodox lifestyle, including an Orthodox literature and science, though not on a large scale. These were transitional years, and immersion in transitional conflicts did not cause Rabbi Hoffmann mental anguish or psychological trauma; “he came and he left in peace.”

[8] He was close with all three leaders at a formative period of his life; he was influenced by all three, but his approach was primarily that of his original teacher, Rabbi Esriel Hildesheimer. Together, they set themselves a goal, and worked towards it jointly throughout their entire lives.

When Rabbi Hildesheimer founded the Rabbinical Seminary in Berlin, as a center of Torah and Science in our time, he called on his student to teach Talmud. Rabbi Hoffmann taught Talmud and halakhic works [posekim] at that institution for forty-eight years. After the founder’s passing, he was appointed Rector of the Rabbinical Seminary (1899). The government and the University granted him the title of Professor (1918) and through old age he never left the Beit Midrash; he taught Talmud and posekim to the students and held a class on Talmud for lay members of the community.

Those who knew him while he was still alive know that his personality was as great as his Torah. One would have to return to the medieval period to witness such a persona among the German or French Hasidim. He was a man with no sense of his own greatness. He exuded humility and everything about him was simplicity. His words, in writing and in speech, were always to the point; he never spoke extravagantly, or used ornate speech, or showed off his knowledge. Truth was the expression of his personality. A measure of spirituality, piety, and modesty resided within his diminutive, silent frame, which was crowned by a brilliant mind. This is exactly how he appeared to me just weeks before his passing. He had attained a sort of calm, an equanimity, contentment, and clarity, which bestowed on him a peaceful beauty. He was always willing to serve even the most minor student; he was never indignant and no one could insult him. This man, who was as diligent in religious observance as one of the ancient righteous [tzadikim ha-rishonim], was shy by nature and humble before God and man. His integrity guided his relationships, without making him bitter or prickly. He had a sense of humor, was pleasant with everyone he met, and could even poke fun occasionally without ever hurting a soul. While his teacher Rabbi Hildesheimer was an activist, he was a “dweller in tents,” inclined to quiet research and study.

As much as he rarely left the “four cubits of Halakha,” he was not removed from daily life. He was well versed in the ways of the world and sensitive to life’s problems. There was no human or Jewish issue with which he was unfamiliar. Although not a political person, he participated in the movements of our people, joined in Orthodox undertakings, and had an appreciation for activism and political movements. In spirit, he was close to Mizrahi, but was an executive member of Agudath Israel, a member of the Aguda’s Council of Torah Sages, and a president of the Orthodox rabbinic association.

[9] (The latter group was ideologically close to the Berlin Rabbinical Seminary and was not radically secessionist. There is another rabbinical association based in Frankfurt

[10] which is completely secessionist, and yet another general union

[11] for rabbis of all camps). He valued equally the undertakings of all those loyal to Torah, and did not exclude even those Jews who rejected separatism. In general, it was not his nature to stand apart, create divisions, or engage in weeding out opponents. He was a true pursuer of peace [

rodef shalom]; he endeavored to abstain from conflict and was not combative in matters of Torah. He debated, but would not attack or behave triumphantly. The very essence of his being was peace [

hotamo hayya ha-shalom].

His German style is clear and simple, without excessive use of flowery expressions. It is the fine language of a scientist, suitable for scientific material; there is gentleness in such simplicity. His Hebrew style is rabbinic, and it too is not weighed down by flowery expression (though occasionally it does show the influence of Haskalah writing). But his Hebrew style is plodding, apparently unable to express modern ideas. Hebrew’s major effort in recent times has been the adaptation of the language to modern concepts, the expansion of word usages, and the substitution of archaic usages with modern ones. He never acquired this level of Hebrew (though we should not think that he opposed the recent effort towards linguistic adaptation). He did not write much in Hebrew. For the most part, he wrote in Hebrew only when he composed halakhic responsa, notes, and a handful of commentaries. For the sake of being recognized by Gentile scholars,

Wissenschaft Des Judentums sacrificed Hebrew on the altar of foreign language. German Orthodoxy committed a comparable sin by abandoning Hebrew in order to level the playing field between Orthodox Judaism and Liberal Judaism. It is a pity that Rabbi Hoffmann’s works were written in a foreign tongue, and were thus destined to have limited influence or value.

[12] In any language, his ideas are properly organized and clearly stated, the ordering and contents are lucid and plain, and there is no strain or drag in his writing. His method is to offer a theory, accompanied by evidence, in a convincing and logical manner.

Rabbi Hoffmann had an extensive, multi-faceted grasp of European learning. He knew classical languages thoroughly, studied Semitic languages, and mastered several European languages. His knowledge spanned the entire range of Enlightenment learning and science.

He was also a great Torah scholar [

gadol ba-Torah], without equal in Germany. We tend to measure a

gadol by

both erudition and intellect. Rabbi Hoffmann was great in both senses, in the sense of the term as used by elite Torah scholars [

lamdanim]. His erudition covered all areas of Torah learning. Unlike those modern scholars who consider the Talmud a subject for antiquarian study, he studied the early and late Talmud commentaries. Talmud was not only fit for historical research; it was a living subject that had never died, whose past could only be explained by its continuity through the ages. He would clarify and simplify, and remove later embellishments. During the course of his teaching and his analysis, complexities became clear. He disliked artificial Talmudic sophistry [

pilpul shel hidud],

[13] but valued Talmudic analysis based on true notions [

pilpul shel emet], which he practiced his entire life. He taught Torah publicly throughout his life; his teaching style was plain and clear. He would explain the topic under discussion in the simplest manner, and those who understood him realized that there was a thesis underlying this simplicity that could resolve halakhic disputes, determine the correct interpretation, and might even refute the opinion of an early or late Talmudic authority. Most scholars who teach Talmud disregard fundamental, introductory principles, relying on previously acquired knowledge; Rabbi Hoffmann did not. He would explain fundamental ideas that could be easily understood. These included synthetic words, popular expressions, halakhic issues, archeology, Talmudic methodology, the structure of Talmudic passages, and their textual context. He would explain all of these matters logically and lucidly.

His responsa

[14] were published posthumously; others edited them for publication. He never intended to publicize them

[15] and most were products of their time [

le-tzorekh sha’a]. For decades, critical issues and complex questions from every corner of Germany were sent to him, by laymen as well as rabbis, who considered themselves his disciples and relied completely on his wisdom. Sometimes, a village rabbi would be confounded by a halakhic question and would travel that day to Berlin to consult with his teacher, or else send a telegram, or write a letter with his halakhic query. He was like the Great Sanhedrin for all German Jewry. Most questions were on contemporary matters that remain of practical interest. Essentially, these were questions on the Jew’s relationship to daily phenomena and technology: Issues related to manufacturing and commerce; social and communal matters; prayer and synagogue practices; questions on electricity and the telephone pertaining to Sabbath law; attending non-Jewish schools on the Sabbath; business arrangements with non-Jewish partners with regard to the Sabbath; laws pertaining to medication on Passover; the question of an Orthodox rabbi presiding over a Liberal congregation; the law on taking an oath bare-headed; shaving for medical reasons; Torah education for girls (he permitted it); women’s suffrage. In his responsa, he determined the halakha in a straightforward manner, by reference to the early and late authorities; he categorized their positions, and arrived at a halakhic decision. There were times when he utilized modern science or critical methods to clarify Talmudic issues. He may cite the writings of natural scientists, quote the opinion of medical experts, refer to scientific works, and then reply with his halakhic ruling. He only rarely engaged in the lengthy give-and-take of halakhic argumentation. For the most part, he simply cited his sources and outlined his halakhic ruling. He did not hesitate to reference halakhic abridgements, which most great Torah scholars normally ignore. In this transitional period, circumstances required setting patterns of daily life and social norms for Judaism within the modern world which, willy nilly, impacted the Jew. An important creation of German Orthodoxy was this model of modern life within which the Orthodox Jew could live without conflict. Rabbi Hoffmann was involved in all of these questions. He helped establish Halakha’s attitude to modern life and set parameters for permitted and prohibited behavior. Some of the questions he was asked by laymen display a real integrity that bring honor to the questioner.

The secular courts regularly consulted with him to clarify points of Jewish Law. He was often called as an expert witness in court at infamous trials, i.e., trials of anti-Semites. These events affected him deeply. When the survival of the German Empire hung in the balance,

[16] I heard him say that this was divine punishment, measure for measure, for the monarchy’s lack of intervention in the trial of Fritsch,

[17] who blasphemed against Heaven. As he said this, his voice shook with emotion. As a result of such trials, he composed his work on the

Shulhan Arukh (first edition, 1885; second edition, 1895),

[18] in which he outlined the role of

posekim in our tradition – even though Rabbi Joseph Karo [

ha-Mehaber] is the normative

posek – and he clarified many details of the laws pertaining to Gentiles. Based on first editions of printed works, he explained the halakhic distinctions between Christians and other Gentiles. This work contains much detailed knowledge and explanations derived from his deep understanding.

The Wissenschaft establishment considered him one of its architects. Wissenschaft is primarily concerned with reconstituting the past from literary remnants, employing an historical-philological method, and embracing all aspects of Judaism. It is conservative by nature. Its originators held traditional beliefs but, over time, it became fundamentally antagonistic to Orthodox Judaism. The Orthodox were distressed over the inability of this heritage to strengthen tradition. The goal of Rabbi Hoffman and his teacher Rabbi Hildesheimer was to fortify the borders of Wissenschaft so that it could not harm tradition, and so that traditional ideology would not be harmed by Wissenschaft scholarship. They were determined to analyze the sources using the scientific method, and were confident that the Torah could not be damaged by true science. He demanded extreme caution, both from himself and from others. Whenever he discovered a conflict between scholarship and Torah he suspected that the conflict stemmed from a lack of precision, from flawed science or from superficial disregard of the sources. He was not narrowly constrained within his field; all of Jewish scholarship and all fields of Torah study were within his purview. Aside from the books he wrote, he published numerous articles. He stood constant guard, responding to every scientific discovery in his fields from the standpoint of both scientific criticism and traditional ideology. The truth of tradition was part of his consciousness. There was no boundary between his Talmudic analyses and his scientific research. He did not employ two methodologies, even if he was a master of two methodologies. He might clarify a halakha using textual variants or historical considerations, and he would employ all the tools of a Torah scholar to confirm details of critical study. For the benefit of critical scholarship, he made available a vast quantity of Talmudic and rabbinic material previously inaccessible to scholars.

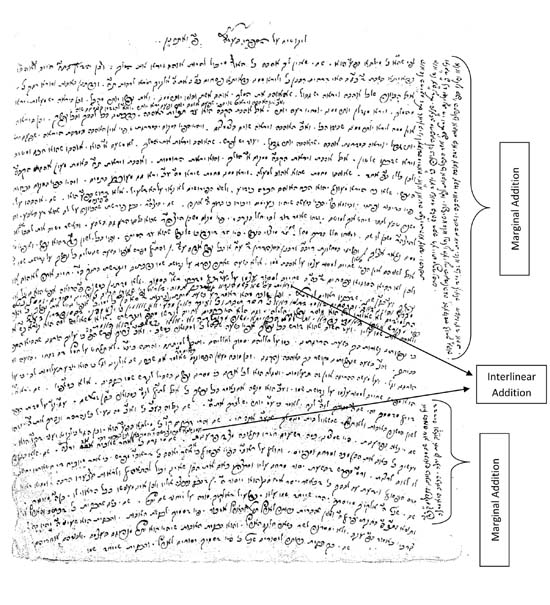

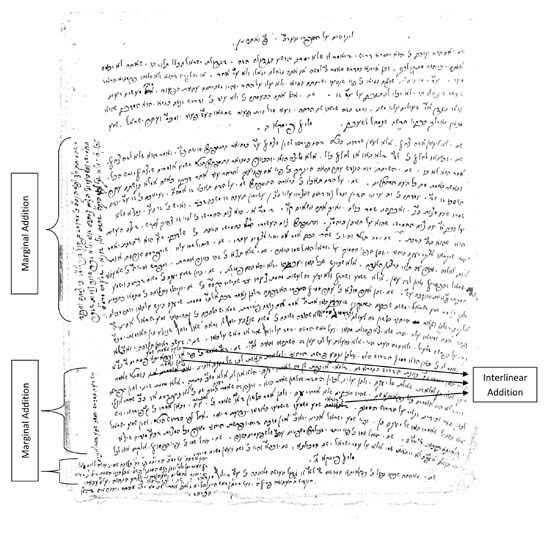

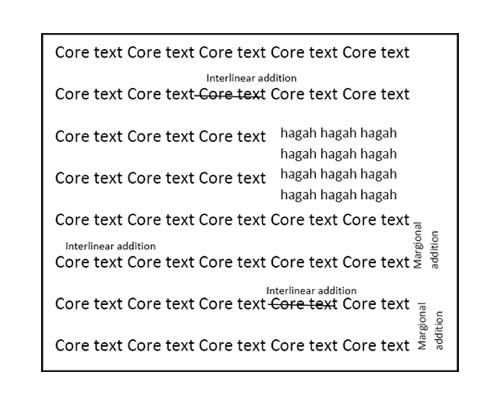

In his book

The First Mishna (1882, and translated into Hebrew by Dr. Samuel Greenberg),

[19] he cast new light on the history of the Oral Law, and laid a foundation for the new field of Mishna criticism. Previously, most scholars believed that prior to our Holy Teacher, Rabbi Judah the Prince, there were only scattered, disorganized, and disjointed halakhot, until Rabbi Judah compiled them. It was considered groundbreaking when someone tried to show that compilations of halakhot were available in the Beit Midrash in Rabbi Akiva’s day. Had this issue come up earlier, many scholars may have hesitated to address it; but the question with its full implications had not yet arisen. Rabbi Hoffmann came forward and proved – with proofs withstanding critical evaluation – that at the time of the elders of the Shamai and Hillel schools there existed a First Mishna, fully complied and having a fixed text. Major mishnayot and basic halakhot in our Mishna derive from the First Mishna, and the very expression

mishna rishona found in the sources is not only meant in contrast to a

late Mishna on a particular halakha, but that this was the title of a compilation of halakhot used in the Beit Midrash during this period. He adduced proofs from mishnayot which, he showed, were from the Second Temple period; from common terminology; from the internal arrangement of the halakhot; and, primarily, from Tannaitic disputes. He believed that for the most part, these disputes were based on disagreements about the original wording and interpretation of the First Mishna, and that the relationship of the later Tannaim to the First Mishna was like that of the Amoraim to the Mishna as a whole. From the time the First Mishna was compiled, it was subject to much editing and came out in several revisions, comprising layer upon layer, until it was finalized in Rabbi Judah’s time. He then attempted to determine, by precise criticism, the makeup of the First Mishna, using internal signs as well as statements of Amoraim who were familiar with the Tannaitic world (though he did not employ enough of the latter method).

As examples he used Tractate

Avot, in which he identified three revisions, and chapters in

Pesahim and

Yoma in which he identified multiple layers. He believed that mishnayot containing halakhic midrash were the oldest. He was of the opinion that prior to the compilation of the Mishna, the Soferim and the Tannaim studied the Oral Law in the format of halakhic midrash, accompanying Scripture. Associated with each verse they transmitted any relevant halakha, accepted interpretation, popular custom, and contemporary statute. These were attached to the biblical words and verses. The Soferim and early Tannaim proceeded from one verse to the next, interpreting each word, and associating halakhot with each and every letter. Mishnayot surviving from this early midrash are embedded in our Mishna, a clear sign that they derive from the First Mishna. Rabbi Yitzhak Isaac Halevy

[20] succeeded him and followed his method (without mentioning his name

[21]), though he disagreed with some of the details of Rabbi Hoffmann’s thesis. Rabbi Halevy dated the compilation of the First Mishna (which he termed the “Foundational Mishna” [

yesod ha-mishna]) earlier, to the period of the late Soferim, the last members of the Great Assembly. This theory is reasonable, but must be considered speculative, while Rabbi Hoffmann’s dating is supported by evidence and can withstand serious critical appraisal. Still, one should not dismiss Rabbi Halevy’s opinion as mere reasonable speculation. One may criticize Rabbi Hoffmann for underemphasizing the notion of gradual, anonymous, literary evolution, which could account for the Mishna’s creation from an historical perspective. Rabbi Halevy also disagreed with Rabbi Hoffmann’s view – a view shared by Rabbi Zechariah Frankel – that halakhic midrash preceded the Mishna. Rabbi Halevy took the opposite position, that the apodictic Mishnayot preceded halakhic midrash, and that the latter defined and restricted the apodictic halakhot. I believe that Rabbi Halevy was unsuccessful in shaking the foundations of Rabbi Hoffmann’s thesis. I believe one must distinguish between the midrash of the Soferim – which derives Halakha from Scripture, and for each new question applies exegesis to Scripture as an halakhic source – and the midrash of the Tannaim, which attempts to support and define previously compiled halakhot.

[22] In one fell swoop, Rabbi Hoffmann illuminated the entire process of the Mishna’s creation, explicated the Tannaitic period, and laid the foundation for the field of scientific criticism of the Mishna, a field whose future is bright. This discipline does not damage traditional belief. On the contrary, it pushes back the date of the Oral Law’s compilation, and thus bolsters the antiquity of tradition.

There is obvious scientific value to his book

An Introduction to Halakhic Midrashim (Berlin, 1887),

[23] in which he defined the evolutionary pathways of halakhic midrash. He discovered two trends or styles within halakhic midrash: One of the school of Rabbi Akiva and the other of Rabbi Ishmael. He identified the signs by which one may distinguish between these two schools: Variations in exegetical style; differences in the names of Tannaim cited; differences in linguistic expression and exegetical structure. He demonstrated that there were once two parallel sets of halakhic midrashim on four books of the Pentateuch, written according to each method. His thesis was validated when it helped discover remnants of Tannaitic midrash. He published these in edited and annotated versions:

1. “On a Mekhilta to Deuteronomy,”

in

Shai la-Moreh (Berlin, 1890)

[24]

2.

Likutei Batar Likute mi-Mekhilta le-Sefer Devarim (Berlin, 1897)

[25]

3.

Midrash Tannaim al Sefer Devarim (Berlin, 1908)

[26]

4.

Mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon al Sefer Shemot (Frankfurt, 1905)

[27]

5.

Midrash ha-Gadol al Sefer Shemot, two volumes (Berlin, 1913-1921)

[28]

Two of these books

[29] were published by the author in complete form; their conclusions are straightforward and they are clear and well-organized. When I discussed these two books with him, he admitted that with respect to his ideas, he was preceded by Rabbi Israel Lewy of Breslau, in the latter’s books

The Mishna of Abba Shaul[30] and

Mekhilta De-Rabbi Shimon.

[31] However, it must be noted that Rabbi Lewy – an unequaled scholar – wrote obliquely, whereas Rabbi Hoffmann constructed fully developed systems. Rabbi Hoffmann also translated and wrote a commentary on Mishna

Nezikin and began work on

Taharot.

[32] He calmly expressed doubt about completing the commentary on

Taharot in his lifetime. Although the translation was intended mainly for laypeople, the commentary includes notes and explanations of lasting value, especially on

Taharot.

Scattered among his articles and responsa are studies on Talmudic philology and Jewish History. He was among the first to use the Samaritan Aramaic translation of the Bible for linguistic study of the Mishna and Talmud. He made emendations to the Talmud; interpreted obscure passages; attempted to reconcile conflicting chronologies; researched the history of the Sanhedrin; resolved difficulties in the writings of Josephus; utilized Jewish Hellenistic literature to explain Talmudic passages; analyzed etymologies of loanwords from Greek and Latin; tried his hand at comparing Hebrew and Aramaic to other Semitic languages; interpreted difficult chapters in Tractate

Midot; elucidated Talmudic archeology; wrote commentaries on liturgy and

piyyutim; and, he founded a scholarly journal which he edited for several years (1876-1893), the

Magazin für die Wissenschaft des Judentums.

[33] He achieved his self-imposed goal: To study Judaism by the scientific-critical method, and to bring respectability to scholarship that is loyal to tradition. His spoke with equanimity and conducted himself with humility. No opponent could act presumptuously toward him, and no one could cast doubt on his commitment to scientific scholarship.

In the end, he crossed over the boundary he had originally set for himself, and engaged in biblical studies. At most rabbinical seminaries in the West, there was no study of the Written Law except for some instruction on medieval commentaries.

Wissenschaft scholars did not study Bible out of fear of taking a stand on fundamental principles concerning the Torah. They did not have the courage to challenge the prevailing opinions of Gentile scholars. Chumash was studied at two Berlin seminaries – at Maybaum’s Liberal seminary,

[34] and also at the Orthodox seminary founded by Rabbi Hildesheimer – since both academies recognized the challenges posed by modern biblical studies, and each had its own unique approach to Torah study. Teaching Chumash at the seminary led him to study exegesis and to analyze the conclusions of biblical criticism. He then wrote his book against Wellhausen, the most prominent biblical critic,

The Principle Arguments Against Wellhausen [

Re’ayot Makhr’iot Neged Velhoizen],

[35] published in 1904, in which he sanctified God’s name by his critique of criticism. He critically assessed the proofs employed by criticism, and highlighted the flaws in its arguments. In this way he attempted to destroy Wellhausen’s structure, removing each level, brick by brick. He especially fought the Documentary Hypothesis, refuting its assumption of multiple textual layers. He revealed its artificiality and its lack of foundation, as well as its internal inconsistencies, using proofs based on the methods and principles of the critics themselves. He refuted their proofs for the existence of separate biblical source-documents, based on the notion of distinctive terminology, by listing parallels between expressions used in the Prophets and in the Torah, thus negating the belief that the Prophets were unaware of sections of the Torah. He cited ironclad evidence regarding internal connections between the sources, showing how they were indeed parallel according to the critics’ own methodology.

After this fundamental work, he devoted himself to publishing his commentaries on Leviticus

[36] and Deuteronomy.

[37] Here he battled the destructive criticism on behalf of Scripture, using every available scientific and deductive weapon. At the same time, by citing a vast quantity of Talmudic and rabbinic material, he demonstrated the contribution of the Oral Law to understanding the simple meaning of Scripture. From one chapter to the next, he pursued critical theory, contradicted each of its conclusions, and made sense of the verses.

He also made an effort, in which he was preceded by several Jewish scholars (Rabbis Naftali H. Wesseley, Meir L. Malbim, J. Z. Mecklenberg), to demonstrate the unity of the Written and Oral Laws, both in the long introduction to Leviticus and within the commentary. He investigated the division and ordering of biblical paragraphs [parshiyot], and even addressed matters of philosophy and the rational justification of the commandments [ta’ame ha-mitzvot]. One might consider his commentary the “Orthodox version” of scientific exegesis. Before his time, Orthodox Judaism was resigned not to respond to criticism, choosing silence instead. He blazed a new path which, however, is not suited for the general public. It is a pity that he did not write his commentaries in Hebrew, but we can rejoice at the fact that his fundamental work against Wellhausen has now been translated.

One might fault him for responding to biblical criticism by negation only; for demonstrating the emptiness of the critics’ proofs but not offering a positive resolution to the problems they raise; for not confronting speculation with certitude; for not proposing a positive theory to resolve inconsistencies in the Torah. It is possible that he intended only to negate, and left the positive response to faith and tradition.

[38]

Six years ago today, on 19 Marheshvan 5682 (November 20, 1921), he passed away at the age of 78. At the time, we all felt that he had no replacement, and that the generation had been orphaned. He was accorded much honor by his students and by all of German Orthodoxy; an honor that cultured people confer on their teachers; an honor that brings honor to those who give it.

There is no replacement for a giant, but there is comfort in his teaching.

May his soul be bound in the bond of life.

19 Marheshvan 5688 (November 14, 1927)