Comments on recent books by R. Benji Levy and R. Eitam Henkin; R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik; and the first color photographs of R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg.

Comments on recent books by R. Benji Levy and R. Eitam Henkin; R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik; and the first color photographs of R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg

Marc B. Shapiro

1. Benji Levy, Covenant and the Jewish Conversion Question: Extending the Thought of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (Cham, Switzerland, 2021)

The last few decades have seen a lot of discussion regarding conversion, and what is and is not required before someone is accepted into the Jewish community. This is obviously a halakhic matter, as conversion is a halakhic procedure and the rabbis supervise it and are the ones to decide who is to be accepted for conversion. The issue also has a sociological component and in the State of Israel it has national and political significance as well. The fact that halakhic conversion standards in the last generation have become stricter, and conversions have even been revoked, shows that we are dealing with a matter that is far from simple. As most are aware, this has led to a good deal of tension in Orthodoxy.

Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903-1993) was the leading Orthodox thinker in the post-World War II era. Combine this with his standing as a great talmudist and it is obvious that he will have important insights in the matter of conversion. It is to this that R. Benji Levy turns his attention in this valuable new book which analyzes the Rav’s halakhic thinking together with his philosophical perspectives. It is a book which all students of the Rav’s thought will want to examine.

Before his discussion of the Rav’s position, Levy deals extensively with earlier rabbinic views on the status of an apostate. This is helpful in and of itself, but also in terms of seeing the novelty of the approach advocated by the Rav. Bringing the Rav’s notions of Covenant of Fate and Covenant of Destiny into the halakhic arena, Levy argues the Rav arrived at his position by positing that holiness is not inherent, something one is born into. As such, one can lose this holiness. For the Rav, this is not only stated with regard to people, as he also that he felt that there is no such thing as holiness “inherent in an object.” Rather, holiness is “born out of man’s actions and experiences” (Levy, pp. 58-59, quoting from the Rav, Family Redeemed, p. 64). As is well known, R. Meir Simcha of Dvinsk had the same perspective. The Rav also offers this perspective when it comes to niddah. See Nathaniel Helfgot, ed., Community, Covenant and Commitment, pp. 325-326: “The entire concept of tum’at niddah, ritual impurity of the menstruant, is not an inherent description, but rather a relational one, for the niddah herself is not ritually impure at all. The ritual impurity expresses itself only in relation to the other.” This is definitely not the mainstream perspective in rabbinic literature.

In chapter 5, Levy gives us a good summary of the different halakhic positions regarding conversion. In the popular mind, this is often reduced to strict or lenient positions. But this is not really accurate, as the fundamental issue under dispute is what exactly does kabbalat ha-mitzvot means. It is often unclear which side is lenient and which is strict. For instance, if a rabbi voids a conversion because someone is thought to have converted without proper acceptance of mitzvot, this can be seen as strict when it comes to conversion. But the voiding of the conversion means that this individual does not need to fast on Yom Kippur, and if he is married he can leave his wife without giving her a get. So from this perspective, the voiding of the conversion is “lenient.”

Levy also calls attention to a fascinating “hiddush” of the Rav when it comes to conversion. According to the Rav, not only does a convert need to accept all the mitzvot, but he must also commit to a life of study of Torah. “A convert who wants to enter the congregation and accept upon himself the yoke of mitsvot, but is unprepared to toil in Torah, this is lacking in their conversion” (pp. 134-135). As Levy notes, this position is in line with the Rav’s stress on serious learning as opposed to the “sentimentality of ceremonialism” (p. 135). Levy adds that this stress on study “achieves a radicalization of the overall conversion process” (p. 135). I wonder, though, is this something that the Rav actually insisted on, or was this simply a point he mentioned in shiur like so many other ideas that sound appealing but are without practical significance? In fact, do we have any evidence that the Rav ever supervised conversions? If so, it would be fascinating to know what he required from future converts and how he guided them.[1]

Levy claims that R. Aharon Lichtenstein’s position in his famous article, “Brother Daniel and the Jewish Fraternity,” is not identical with the Rav’s outlook. This was surprising to me, as it is generally understood that R. Lichtenstein’s 1963 article was an attempt to explain the Rav’s approach in the wake of the Brother Daniel episode. Levy, p. 84, quotes the Rav as saying that “however much an irreligious Jew attempts to cast off his faith, he is fated to be unsuccessful.”[2] He contrasts this with R. Lichtenstein’s statement that there is “a point beyond which the apostate cannot go and yet remain a Jew” (p. 84). Yet these statements are not in opposition. The Rav is referring to an irreligious Jew, not an apostate. A document I recently published which quotes the Rav’s explanation of his position makes this very clear.[3] It also shows that R. Lichtenstein’s points are directly in line with those of the Rav, and knowing their relationship, the article itself must have been written under the close guidance of the Rav.

Usually people think of Jewish identity as an inherent part of someone, an inheritance that cannot be given up. Yet the Rav departs from the usual approach and considers Jewish identity as something that can be lost, but only in extreme circumstances. One who is not religious does not lose his halakhic standing as a Jew. However, one who actually converts to another religion is regarded by the Rav as having severed his connection to the Jewish people, and for most intents and purposes would no longer be regarded as Jewish. (I do not know how he would regard the child of an apostate woman.)

As such, I must also reject Levy’s conclusion that for the Rav a Jew may lose his individual holiness, but his “holiness qua member of the Jewish collective is unshakeable.” It is this point that I believe to be mistaken, and as noted already, I assume that the Rav’s settled position is as explained by R. Lichtenstein. I also believe that we need not be concerned that in shiur the Rav offered a different reading of a text, as what he said in shiur was often provisional, an exploration of different possibilities.[4] In the case at hand we have more than one testimony that R. Lichtenstein’s description, that in many ways an apostate is not to be regarded as Jewish, is exactly in line with the Rav’s position. With this in mind, we also need to review Levy’s discussion of the Brother Daniel controversy (pp. 186f.). To say that the Rav supported the ruling of the Israel Supreme Court and leave it at that creates a misinterpretation. Yes, the Rav agreed with the Supreme Court that Brother Daniel was not to be regarded as Jewish. Yet the Court’s assumption was that halakhah would regard him as Jewish. However, since the Law of Return is a secular law, the Court had to decide based on how the law was understood by “the ordinary simple Jew,” and such a Jew would never regard a Catholic religious figure as being part of the Jewish people. The Rav could not be more adamant that the Court was in error, as in his view, even from a purely halakhic perspective, Brother Daniel could not be regarded as Jewish.[5]

One final point: Levy deals with authorities who have seen circumcision or immersion as conveying what can be termed “limited sanctity” or “partial conversion.” There is another source that should be added to this discussion. R. Hershel Schachter records the Rav’s understanding that the Patriarchs had moved beyond the status of benei Noah, but had not yet achieved the full status of kedushat Yisrael. Nevertheless, they still had some kedushat Yisrael.[6] This puts them somewhere between non-Jews and Jews, a “partial Jew” if one might use the term.

2. Eitam Henkin, Studies in Halakhah and Rabbinic History (Jerusalem, 2021).

It has been eight years since the murder of R. Eitam Henkin, and the deep sadness over what was taken from us remains. A glance at what Henkin was able to accomplish in his short life— three books and numerous articles, all of the highest caliber—shows us what the future would have held for him in both rabbinic and academic scholarship. As Eliezer Brodt puts it in his introduction to Henkin’s Studies in Halakhah and Rabbinic History: “He was a unique combination of an outstanding talmid hakham and historian who was also blessed with exceptional research and writing skills.” Fortunately, in his short years R. Eitam left us with much to treasure.

Studies in Halakhah and Rabbinic History, published through the great efforts of Seforim Blog editor Eliezer Brodt, is a treat for anyone who values Torah and Jewish scholarship. All of us are in great debt to Brodt for this labor of love, which began immediately after Henkin’s murder, when Brodt was the prime mover behind the publication of Ta’arokh Lefanai Shulhan, Henkin’s posthumously published book on R. Jehiel Mikhel Epstein and the Arukh ha-Shulhan. The essays in the current volume are translations of many of Henkin’s important Hebrew articles, and the translators, volunteers all, also deserve our great thanks.

The first section of the book focuses on halakhah. R. Eitam deals with the kosher status of strawberries, modern utensils and absorption of taste, the sale of land in Eretz Yisrael to non-Jews, and other topics. The second section, which has more than 250 pages, deals with the girls’ dance on the 15th of Av, the famous (or infamous) Bruriah story, the Shemitah controversy, the Novardok yeshiva, haredi revisionism when it comes to Rav Kook, and a number of other topics. The final section focuses on R. Joseph Elijah Henkin, offering a general survey of his life and significance, and a second article dealing with his statements about R. Shlomo Goren and the Langer Affair.

There is so much that can be said about this this rich book, but in the interests of space I will only offer a few comments. I am certain that in future posts I will have the opportunity to come back to it.

In chapter 2, Henkin discusses the fascinating issue of absorption of taste in modern utensils. If the halakhic concept of beliah is based on actual absorption, then when dealing with stainless steel, which does not absorb, the halakhic issues should disappear. Following this line of thinking, it could still be appropriate, for a variety of reasons, to have separate meat and dairy stainless steel utensils. But if one mistakenly cooked dairy in a meat stainless steel pot that had been used with meat in the last day, bediavad the food should be OK to eat and the pot should not need to be kashered. If one were to follow this approach, stainless steel would be treated just as Sephardim treat glass, which can be used for milk and meat as the glass does not absorb.

In response to such a claim about stainless steel, Henkin puts forth the original argument that the real issue is not the new type of materials we use for utensils, but that our ability to perceive taste is not what it used to be. In other words, if our taste buds have deteriorated, then we can no longer use them as the basis of determining if there are beliot.

To prove that our sense of taste has weakened compared to the days of the Sages, Henkin did an experiment:

I took a wooden spoon (an old one, like utensils in the average kitchen) and for about half a minute I used it to stir milk that had been boiled in a glass cup. I then washed the spoon well, and then stirred with it, also for a half minute, about half a cup of tea which had been boiled in a small metal pot (a cezve). At the same time, I stirred the same amount of tea using a new metal spoon. I tasted it myself and gave it to my family to taste (as mesihim lefi tumam, without knowledge of the experiment) and no one could discern any difference in taste between the cups. Even when the family members were asked to guess which of the two cups was “dairy,” the success of the guesses wavered as expected at around 50% (pp. 25-26).

The results he obtained led Henkin to conclude that our sense of taste has weakened. This is because it is clear from the talmudic sages that milk leaves a taste in wooden spoons, and yet in reality we see that this is not the case.

This is a very interesting point that I will leave to scientists to discuss, but I do not think it fundamentally changes the problem. Even if our sense of taste has weakened, and we cannot taste what in previous generations we would have been able to, the fact is that stainless steel by definition does not absorb taste. So even if in the days of the Sages they could sense the flavors absorbed in wood, they would not have been able to taste anything had they used stainless steel. Thus, we return to the question of whether there should be a halakhic concept of beliot when it comes to stainless steel.

I must also mention that Henkin’s teacher, R. Dov Lior, specifically states that one can use stainless steel for both meat and dairy (although in practice he requests that two other poskim agree with this position). [7] I find it hard to believe that this will ever become an accepted practice, but is there any halakhic reason why not, or is it only be a matter of continuing what we have done in the past even if there is no strict halakhic reason to do so? Must we assume, as stated by R. Yaakov Ariel, that the entire concept of beliah is a halakhic notion, which like other halakhot operates according to its own rules that are not tied to scientific facts?[8]

Finally, I must note that unfortunately when the essays were translated no attention was paid to Henkin’s website here. On occasion, Henkin corrected his essays, and when the essays were translated R. Eitam’s corrections should have been included. For example, in chapter 24 he discusses R. Shlomo Goren and the Langer affair. On p. 413 n. 17, he mentions various rabbis who were identified as having been on R. Goren’s special beit din that concluded that the Langer children were not mamzerim. Yet on his website here he notes that two of the names he mentioned are not correct. There are other articles of his where he added more material on the website, so readers who want the most up-to-date scholarship of Henkin are recommended to check there.

3. At the end of my last post I mentioned that the next post would include an unknown article by R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik. I was mistaken, for not only is the article not unknown, but it is also included in R. Nathaniel Helfgot’s collection of the Rav’s letters and public statements, Community, Covenant and Commitment, pp. 263-265. Helfgot tells us that the article appeared in the Rabbinical Council Record (no date is given). I thought it was unknown because I found it in Jewish Horizon, Sep.-Oct. 1964, and didn’t at first realize that it was also reprinted in Helfgot’s book. What accompanies the Rav’s article is another article that is pretty much unknown. Although it is recorded in the bibliography of R. Lichtenstein’s writings found here, I have never seen anyone refer to it. While new material from the Rav is obviously very exciting, the same can be said for anything from R. Lichtenstein’s pen.

Since I promised something new from the Rav, how about the following which I believe is the first time that the Rav’s name ever appeared in print. It is from the German Orthodox paper Der Israelit, February 7, 1929, and mentions the shiurim for advanced students that the Rav delivered at an Ezra youth movement gathering in Berlin.

In my Torah in Motion classes on the Rav’s letters, available here, I also discussed the Rav’s reason for rejecting numerous pleas that he put forth his candidacy for the Israeli Chief Rabbinate after the 1959 death of R. Isaac Herzog. A lot has been written about this episode.[9] However, we also have the Rav’s testimony from the 1970s that he was again approached about becoming Chief Rabbi.[10] And there is even one other testimony about the Rav and the Chief Rabbinate, but this time I am referring to the Chief Rabbinate of the United Kingdom. Bernard Homa, Footprints on the Sands of Time (Gloucester, 1990), p. 127, writes as follows about the discussion of who would succeed Chief Rabbi Joseph Hertz:

I was one of the representatives of the Federation on the London Board for Shehita, where I served as Vice-President from 1946 to 1948. I also represented the Federation in 1947 on the committee, under the Chairmanship of Sir Robert Waley Cohen, dealing with the appointment of a successor to Dr. Hertz, who had passed away in 1946. I recall two items worthy of mention. Among the several names that came up was that of the famous Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik of Boston. There was no discussion as to his merits but he was quickly excluded from consideration for a very silly reason. The Chairman reported that he had been informed that he did not know how to use a knife and fork properly.[11] His informant was clearly unaware that in the U.S.A. table customs are different from those in this country and the allegation against him was thus not only trivial, but entirely without foundation.[12]

In my article in Hakirah 32 (2022), I published a number of letters from the Rav. Let me share an additional letter, to R. Irwin Haut, which was originally supposed to be included in my article. Unfortunately, I only have the first page. (The family also only has the first page. If any reader has the complete letter, please be in touch.) I thank Professor Haym Soloveitchik for granting me permission to publish it.

י“ג אדר השני, תשי“ט

March 23, 1959Dear Rabbi Haut:

Acknowledge receipt of your letter.

1. Liquids which were cooked or boiled before the Sabbath and remained on the covered gas range during the בין השמשות period may be put back, after being removed for the night to the refrigerator, on the covered flame on Saturday morning, provided that the liquid foods do not reach the temperature of יד סולדת. If, however, the liquids are kept near the flame so that their temperature remains above the house temperature, we do not have to concern ourselves with the aspect of יד סולדת.

2. I would advise you to put a a [!] tin or tin-foil cover on the [next page missing]

The issue here is heating up liquids on Shabbat, and the position of the Rav is more liberal than the standard Orthodox approach today which is not to allow any reheating of liquids (other than Yemenite Jews who follow Maimonides’ opinion). To understand the Rav’s position, we must first note that this was actually the opinion of his mother, Rebbetzin Pesha, who was a scholar in her own right. In this case, I think we can say that the Rav was simply following his family tradition.

This is what appears in Yeled Sha’ashuim, p. 30, a book devoted to R. Ahron Soloveichik[13]:

Rebbitzen Pesha would place cold soup on the hot Shabbos blech and be careful to remove the soup before it became יד סולדת בו. She was not concerned about the איסור חזרה because the psak of the Rama is that if the food was on the Shabbos blech for the duration of בין השמשות on Friday night and was later removed from the Shabbos blech, then there is no איסור חזרה. The only question then is whether there it is forbidden from the standpoint of the איסור בישול. Rebbitzen Pesha reasoned that it is permitted to do this on the basis of ספק ספיקא. First of all, there is a מחלוקת ראשונים as to whether in דבר לח we say אין בישול אחר בישול. The view of חכמי ספרד is that even in דבר לח we say אין בישול אחר בישול. But, in this case, one removes the soup from the Shabbos blech before it reaches the heat of בישול. The soup becomes only lukewarm. There is a מחלוקת רש“י ותוספות whether this is permitted or it is אסור מדרבנן גזירה שמא ישכח וזה יגיע לידי בישול. The question in this case revolves only around an איסור דרבנן. Rebbitzen Pesha, therefore, reasoned that it is permitted on the basis of ספק ספיקא.

Quite apart from the specific issue of liquids, the Rav’s position allowing food on the blech or even in the oven during bein ha-shemashot to be placed in the refrigerator and returned to the blech or oven the next morning is well known and has been discussed by many. This leniency can be traced to R. Nissim of Gerona who derives it from the Jerusalem Talmud.[14] Let me, however, me add two points. The first is that R. Ahron Soloveichik told me that I could adopt this position in practice. (I only asked about food, not liquids). The second point is that the Rav’s position has been portrayed as only referring to foods, not liquids. Yet we see from his letter to Haut that he, together with his mother, also held this position with regard to liquids.

Having said this, I think people will find the Rav’s instructions to caterers at the Maimonides school of interest. I thank Steven DuBois for calling my attention to this document, which is found here.

In one of these instructions I think it is obvious that the Rav was adopting a more stringent approach because he was dealing with caterers, who will not be as careful in these matters as individuals at home. As you can see, the Rav only mentions removing solid foods from the refrigerator, but nothing about liquids. I think the reason is clear. An individual at home can be careful that liquids not reach the level of yad soledet bo, but this is not something the Rav was willing to entrust to a caterer who while busily preparing the Shabbat meal will often not be so careful to make sure that the liquid does not reach yad soledet bo.

We only have the first page of the Rav’s letter to Haut, but it is clear that the Rav’s second point is his advice to put a tin or tin foil cover over the stove knobs in addition to the blech. He does not state this as an absolute requirement but as a preferable procedure. However, in his instructions to caterers, this is listed as a requirement.

Let me share some more things related to the Rav, the first one of which comes courtesy of Ovadya Hoffman. In 1993 R. Yitzhak Hershkowitz published the first volume of his responsa Divrei Or. The second section of this volume includes responsa from the sixteenth-century scholar R. Abraham Shtang. In the introduction we find the following sentence:

אחדים מתשובות אלו נדפס ביובל ע“י ר‘ יצחק זימער

This is a very strange sentence, because what does נדפס ביובל mean? It actually refers to the 1984 Sefer Yovel for R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik where Yitzhak (Eric) Zimmer’s article appears (and Zimmer himself spells his name זימר). As Hoffman notes, this is a sort of “the wise will understand” reference. The editor did not feel that his readership could “handle” the actual title of the book, so instead he refers to it in code.

Growing up, maybe the first thing I knew about practices of the Rav was that he stood up with his feet together for the entire repetition of the Amidah. I recall how certain YU students would imitate this practice of the Rav, which sometimes created problems when people would try to exit the row while the students were standing with their feet together. Regarding the Rav’s practice, see R. Schachter, Nefesh ha-Rav, pp. 123-124, and here.

Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Tefillah 9:3, actually explicitly states: “Everyone – both those who did not fulfill their obligation [to pray] and those who fulfilled their obligation – stands, listens, and recites ‘Amen’ after each and every blessing.” You cannot be much clearer than this, but nevertheless, there are those who offer a different interpretation of Maimonides. According to them, when Maimonides writes והכל עומדין ושומעין it does not mean literally to stand. Rather, עומדין ושומעין means to be quiet and listen. This argument is made by R. Ovadyah Hadaya[15] and R. Isaac Liebes,[16] and they both make the same point in support of their position. R. Moses Isserles, Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 124:4, writes: “There are those who say that the entire congregation should stand when the prayer leader repeats the prayer. (Hagahot Minhagim).” Both R. Hadaya and R. Liebes note that R. Isserles could have cited Maimonides to support the view that the congregation should stand for the repetition of the Amidah. The fact that he instead cites Hagahot Minhagim shows that R. Isserles also did not understand Maimonides to literally mean that the congregation stands.

The problem with this is that R. Hadaya and R. Liebes were unaware that the reference to Hagahot Minhagim, and all similar references to books in parenthesis, does not originate with R. Isserles. It was added by a later editor, and thus the point made by R. Hadaya and R. Liebes has no relevance to R. Isserles’ opinion.

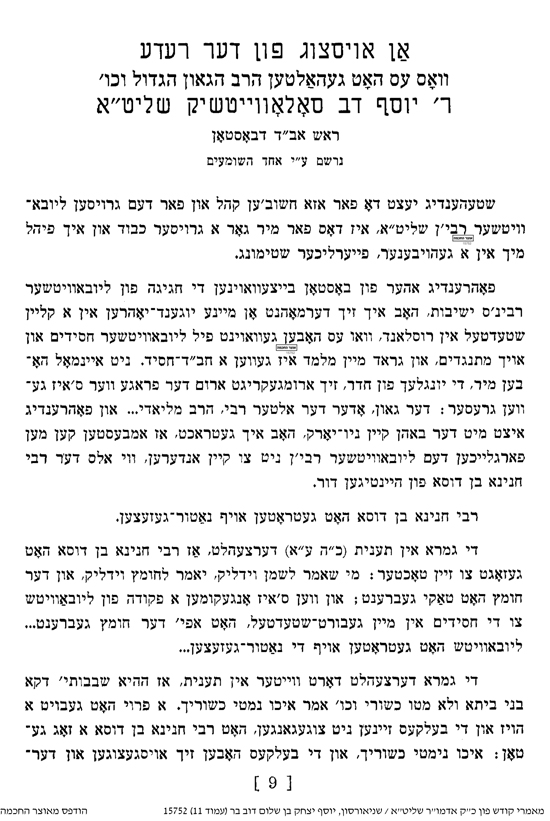

Two more points about the Rav: I do not think it is widely known that one of the first publications of the Rav—based on notes of a listener—appeared in a Habad publication in 1942. Here is the title page which on Otzar haChochma is called מאמרי קודש פון כ“ק אדמו“ר שליט“א.

Here is the first page of the Rav’s article.

In a few of my online classes I dealt with the Rav’s opinion that even in contemporary times the hazakah of tav le-meitav tan du mi-le-meitav armelu (that a woman prefers almost any husband to being single) remains applicable. Here is what appears in R. Elyashiv’s Kovetz Teshuvot, vol. 4, no. 117. It sure seems like R. Elyashiv is rejecting the approach of the Rav.

4. In my post here I stated that Saul Lieberman began his studies at the Hebrew University in 1928. This information is based on Elijah J. Schochet and Solomon Spiro, Saul Lieberman: The Man and His Work, p. 8. However, a reader points out that in the August 16, 1927 entry of the unpublished diary of R. Mitchel Eskolsky, who was studying in Jerusalem at Yeshivat Merkaz ha-Rav, he speaks of meeting Saul Lieberman who was at that time a student at Hebrew University.

Regarding Lieberman, I thank Aron Rowe who called my attention to the fact that JTS has put some talks of Lieberman online. Before this, I had never heard Lieberman’s voice. See here, here, and here.

For those interested in Lieberman, I recently did eighteen classes on him. You can find them on Youtube here, and they are also currently being turned into podcasts which are on Spotify and other platforms. One interesting point about Lieberman which I did not mention is found in his letter to Gershom Scholem, dated July 10, 1967. (Lieberman’s letters to Scholem are found at the National Library of Israel.) Here he states that he was upset that he was not in Israel during the Six Day War, which would have enabled him to suffer together with Israel’s inhabitants. He comforted himself with the knowledge that he was able to have more of a positive impact in the U.S. than his presence would have had in Israel. He tells us what he has in mind, namely, that he permitted collecting money for Israel on the holiday. As Dr. Aviad Hacohen has pointed out to me, this must be referring to Passover, when tensions between Israel and its neighbors were already at a high level, rather than Shavuot, which came out after the war was over. Here are Lieberman’s words:

הצטערתי מאד שלא הייתי בארץ לפני פרוץ המלחמה ובפריצתה ולא זכיתי להצטער עם הציבור במקום הדאגה והצער, ונֶחׇׇמׇתי היא שהבאתי תועלת כאן הרבה יותר מאשר מציאותי בארץ. התרתי כאן לאסוף כספים ביו“ט, והרבנים שלנו פחדו לעשות כן בפומבי, ופסקתי להם שיטילו את כל האחריות עלי. מעניין שהרבנים האורטודוקסיים שהתנגדו לכך לא פצו אח“ז את פיהם למחות נגדי. אני מכיר יפה את אמריקה ואת ההתלהבות הגדולה שהיא גם עלול להצטנן קצת במשך שעות

We see that his pesak was for the Conservative movement, and when he says “our rabbis,” he means the Conservative rabbis, which he distinguishes from the Orthodox rabbis.

When people think of Lieberman they often think about another instructor in Talmud at JTS, namely, Rabbi David Halivni. I think readers will enjoy two recent publication by Zvi Leshem that record all sorts of interesting stories about Halivni, much like similar collections have been put together about so many great rabbis. See here and here.

Regarding Halivni, the following is also of interest. In 2006 a two-volume book about R. Menahem Mendel Hager of Visheva was published, Ha-Gaon ha-Kadosh mi-Visheva. Here is the title page.

R. Menahem Mendel was the grandfather of Halivni’s wife, and in the second volume there is a dedication from Halivni and his sons in memory of her. Notice how Halivni is referred to as Ha-Gaon and shlita.

5. Unlike today where there are thousands of color pictures of the current gedolim, in the past pictures of great rabbis were uncommon. Just think of the few that are available of for each gadol who lived before the Second World War. When it comes to R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, who died in 1966, we have a good number of pictures of him. However, until now no color pictures of R. Weinberg have ever appeared. I am happy to present the only color pictures of R. Weinberg that I have ever seen. They were taken by R. Weinberg’s nephew, Dr. David Corn, on a visit to Montreux in 1958 or 1959. I thank the Corn family for granting me permission to publish these pictures. The originals are now kept at Ganzach Kiddush Hashem in Bnei Brak.

In this picture we see a young R. Yitzhak Scheiner and a young R. Aviezer Wolfson on the right. Thanks to R. Jeremy Rosen for the identification of R. Wolfson.

Here is Dr. Corn with R. Weinberg.

Here are the remaining pictures he took.

6. In July 2023 I led what I was told was the first ever kosher tour to Tunisia, courtesy of Torah in Motion. Seeing this unique Jewish community up close was an amazing experience for all.

Here is a beautiful picture from last summer’s trip to Tunisia. The photographer is Alan Messner and it was taken in Djerba. (I encourage everyone who studies Talmud Yerushalmi to check out Alan’s valuable index here.)

Quiz

Please identify the following and email me your answers:

1. There are two se’ifim in the Shulhan Arukh that only contain two words.

2. There is one siman in the Shulhan Arukh whose number is the gematria of the subject of the siman.

Coming next: More on Saul Lieberman, and R. Moshe Zuriel: A Great Teacher in Israel

* * * * * * *

[1] Regarding the Rav and converts, in R. Chaim Jachter’s fascinating new book, Gray Matter, vol. 5, p. 163, he mentions that in a 1985 shiur the Rav stated that non-Jews have a “right to convert.” R. Jachter elaborates on the halakhic implications of this notion.

[2] David Holzer, ed., The Rav Thinking Aloud (Miami Beach, 2009), p. 319.

[3] “Letters from the Rav,” Hakirah 32 (2022), p. 152. Here the Rav is quoted as attributing his position to his father, R. Moses. However, in Reshimot Shiurim: Yevamot (ed. Reichman), p. 211 (to Yevamot 17a), it is attributed to his grandfather, R. Hayyim. After mentioning R. Hayyim’s position that descendants of Jews in Spain who identify as Christians are to be regarded as non-Jews both le-humra and le-kula (meaning their children are also not halakhically Jewish), he adds: והוא חידוש נורא. Levy, p. 82, refers to this page in Reshimot Shiurim, but he focuses on the first possible explanation that the Rav offers, rather than the explanation of R. Hayyim which in practice was what the Rav adopted.

I have to say, however, that the Rav seems to have contradicted himself in a 1965 interview with Ha-Aretz (printed in Community, Covenant and Commitment, pp. 220-221). He stated:

During the “Brother Daniel” episode, I wrote to the Chief Rabbis urging that they should stop attempting to decide this issue according to [formal] Halakhah and decide it based on their emotions. Acccording to [formal] Halakhah, Brother Daniel is a Jew. . . . I prayed that the Justices would not follow the Halakhah.

I must also note that during the Brother Daniel episode in the early 1960s there was only one chief rabbi, R. Isaac Nissim.

[4] It might be an interesting project for someone who listened to many of the Rav’s online shiurim to put together a list of ideas he expressed that are not found in his writings or that are in contradiction to what he wrote. I am sure that there are plenty of examples where the Rav offers an idea that he is not sure about and never would have included in a published work. This is obviously relevant to how much weight we give passages in the series of books The Rav Thinking Aloud.

I thought of this when I read the summary of the Rav’s YU graduate school lecture from the late 1940s published in Hakirah 27 (2019), p. 51:

The commandment of lo tirtzah was not [meant to be] self-evident to the intellect. It is also a hok, as is the eating of hazir. The only difference is that it fits into our moral concept of thinking, whereas hazir doesn’t. [It is not obvious] reasoning that I should not murder someone who stands in my way.

Was this really the Rav’s settled opinion, or was he just trying to be provocative with the students, in order to bring out a point? I do not see how the Rav could have really thought that lo tirzah is a hok, and I do not know of anyone who has made such a claim. After all, the prohibition of murder is one of the Noahide Laws, none of which are hukkim.

In Community, Covenant and Commitment, p. 333, the Rav accepts that there are “rational laws.” He adds that when the Jews were commanded about rational laws, “an internal-natural instinct was transformed into a Divinely revealed command.” Furthermore, “the normative field of operation was expanded and deepened and reached the depths and farthest boundaries of idealism, which are unknown to the psychological instincts and predilections.”

In Shiurei Harav, ed. Joseph Epstein (Hoboken, 1974), p. 114, the Rav includes lo tirtzah among the mishpatim, but here too he seems to be denying what we can call a natural law prohibition against murder according to R. Akiva. If one were to follow this approach, I do not see how the prohibition against murder can be regarded as a mishpat.

R. Akiva is saying that since you said “Do not murder,” we don’t murder; but if you did not say it, we might do it. R. Ishmael says that even without God, man would know better. For R. Akiva, a man is capable of murder and is stopped only because of God.

Today, not much proof is needed of R. Akiva’s point of view. There is some devil in man; some satan who can suddenly come to the fore. To prevent this, we need the word of God. For R. Akiva, the mishpatim, those rules for which we think we know the reason should be done on the same basis as the hukim, for which we do not know the reason.

Some might wish to bring proof that the prohibition against murder can be seen as natural law since God judged Cain guilty of murder and this was before the giving of the Torah. Yet this is not a strong point because according to Bereishit Rabbah 16:6, and see also Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Melakhim 9:1, Adam was already commanded against murder. Yet the fact remains that non-Jews are forbidden to murder, and are called to account for violation of this command. This applies even if they had never heard of God’s revelation to Noah or Moses. Doesn’t this mean that this law is in principle knowable by reason?

Marvin Fox has a different approach.

“Ye shall keep my statutes (Lev., 18:5). This refers to those commandments which if they had not been written in Scripture, should by right have been written. These include the prohibitions against idolatry, adultery, bloodshed, robbery and blasphemy [Yoma 67b].” There is no suggestion here that human reason could have known by itself that these acts are evil, nor is it suggested that they are not consistent with man’s nature. What is asserted is only that, having been commanded to avoid these prohibited acts, we can now see, after the fact, that these prohibitions are useful and desirable.

Fox. Interpreting Maimonides (Chicago and London), p. 127. When it comes to Maimonides, the crux of the problem revolves around Guide 2:33 where he categorizes murder (and the other final seven commandments of the Ten Commandments) as belonging to the “class of generally accepted opinions,” as opposed to the first two commandments which are rational, “knowable by human speculation alone.” For the most recent discussion of Maimonides and Natural Law, see Shalom Sadik, Maimonides: A Radical Religious Philosopher (Piscataway, N.J., 2023), ch. 4.

In the Hakirah article mentioned earlier in this note, the Rav also states as follows:

Those who possess greater knowledge and skill possess also the higher ranks in society. Yet Judaism tried to equate the dignity of every individual regardless of his possession of knowledge. [It differentiated] only in regard to his intellectual drive. Where Judaism gave preference to the hakham over the am ha’aretz, it was not with regard to his accumulation of wisdom but simply because he was engaged in this great ethical drive. If a man tries and fails, he is not condemned. [Rather] he receives equal respect [to that] of the hakham.

These are nice sentiments, but the Rav knew full well that this was never how Jewish society functioned. The am ha’aretz, even one who tried, and failed, to become learned in Torah, was never given equal respect to the hakham.

In reading over this note, I see that I have another point to add. I wrote: “After all, the prohibition of murder is one of the Noahide Laws, none of which are hukkim.” I do, however, know of one source that disagrees with my statement. R. David Kimhi, Commentary to Gen. 26:5, writes:

גם יש בשבע מצות שנצטוו בני נח שאין טעמם נגלה אלא לחכמים והם הרבעת בהמה והרכבת האילן ואבר מן החי לפיכך אמר: חקותי, ואמר: מצותי, כלל לכל המצות השכליות בין בלב, בין ביד ובין בפה מצות עשה ולא תעשה

This is a problematic passage. Leaving aside his assumption that ever min ha-hai is a hok, the other two examples he gives, mixed breeding of animals and grafting of trees, are not included in the Seven Noahide Laws. There is a dispute among the rishonim if these actions are forbidden for non-Jews. Those who hold they are forbidden see these as additional prohibitions separate from the Seven Noahide Laws.

In a future post I will deal with the issue of positive commandments that non-Jews might be obligated in. These are also not included in the Seven Noahide Laws which are only negative commandments.

[5] See my “Letters from the Rav,” p. 151.

[6] Eretz ha-Tzvi, p. 140. This is noted by R. Chaim Jachter, Gray Matter, vol. 5, p. 188.

[7] See p. 25 n. 7, where Henkin tells us that after presenting his approach to R. Lior the latter agreed that one should also perform a comparative analysis with stainless steel and other materials. It does not appear that this would have any impact on his halakhic decision, and he has not publicized a retraction. I would say to R. Eitam, and I regret that I did not have the opportunity to do so in his lifetime, that if scientifically it has been shown that there is no absorption in stainless steel, then as I mentioned in the text, I do not see why the comparative study he suggests accomplishes anything.

[8] See his letter in Ha-Ma’yan 53 (Tevet 5773), pp. 90-93. See also the discussion in Nadav Shnerb, Keren Zavit (Tel Aviv, 2014), pp. 314-322.

[9] See Jeffrey Saks, “Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik and the Israeli Chief Rabbinate,” B.D.D 17 (2006), pp. 45-67. See also the lengthy new article by Aviad Hacohen which focuses on the 1935 candidacy of the Rav for chief rabbi of Tel Aviv, but also discusses the period after R. Herzog’s death, “Ki mi-Neged Tir’eh et ha-Aretz ve-Eleha lo Tavo,” in Dov Schwartz, ed., Tziyonut Datit 9 (2023), pp. 153-222.

[10] See David Holzer, ed., The Rav Thinking Aloud (n.p., 2009), p. 143.

[11] R. Meir Mazuz, Mi-Gedolei Yisrael, vol. 1, pp. 197-198, points out that in the first printing of R. Hayyim Joseph David Azulai (Hida), Ma’agal Tov (Livorno, 1879), the printer omitted the details that the Hida recorded about the way Jews in Tunis ate, which their coreligionists in Europe would have viewed as distasteful. This was restored in the Freimann edition, Ma’agal Tov ha-Shalem (Jerusalem, 1934). One of the things the Hida mentions is that in Tunis they ate with their hands, and you can see how uncomfortable it made him (p. 56):

ואוכלים בידיהם ורגליהם וכל שמנונית מלא חפניהם והיה מגביה הגביר חתיכת שומן בעודה בכפו יבלענה ומנקה ידו במטפחת שעל ברכיו והמטפחת נעשה כבית המטבחיים

“And they eat with their hands and with their feet, and with all the fat are their hands filled: the g’vir would lift up a piece of fatty meat and, while holding it in his hand, would he swallow it and then wipe his hands on a towel on his knees; and this towel would become like a butcher’s shop.”

The Diary of Rabbi Ha’im Yosef David Azulai, trans. Benjamin Cymerman (Jerusalem, 2006), Part 2, p. 20.

R. Yisrael Dandrovitz has a fascinating article devoted to the issue of eating with silverware, including the dispute over whether the sages of the Talmud ate with silverware or with their hands. He also deals with the practice of many hasidic rebbes to eat with their hands (some only eat fish with their hands). See “Al Ketzeh ha-Mazleg” Etz Hayyim 21 (5774), pp. 238-269.

[12] I was skeptical about this report of the Rav being considered, and wondered if Homa had remembered correctly. But R. Abraham Lieberman called my attention to Meir Persoff, Hats in the Ring: Choosing Britain’s Chief Rabbis from Adler to Sacks (Boston, 2013), p. 116, where we see that the Rav was indeed one of proposed candidates. The documentary evidence provided by Persoff contains nothing about the Rav’s table manners as a reason for him not being invited to interview for the position of Chief Rabbi.

[13] See also R. Bezalel Naor’s letter in Or ha-Mizrah, Nisan 5766, p. 192 n. 1. R. Naor, who is nothing less than a treasure in the world of Jewish scholarship, continues to amaze with his many contributions. His most recent book is Souls of the World of Chaos, which while focused on Rav Kook also encompasses the entire range of Jewish thinkers.

[14] Shabbat 17b in the Rif pages, s.v. u-mihu.

[15] Yaskil Avdi, vol. 2, no. 2.

[16] Beit Avi, vol. 3, no. 115:6.