Kitniyot and Mechirat Chametz: Paradoxical Approaches to the Chametz Prohibition

“Contemporary Rabbis don’t bother to interrogate the sources of law and custom; instead, their purpose is to traffic in chumrot and create new prohibitions. They are unable to appreciate their hypocrisy … on the one hand, they roar like a lion against those who are open to change and the reformists, that one cannot alter an iota from what the kadmonim imposed, while on the other hand, casually discard the kadmonim whenever the achronim create new chumrot and they fight with all their might…to impose these new prohibitions.”

R. Yitzhak Shmuel Reggio, Yalkut YaShaR, Gorizia 1854.

Kitniyot and Mechirat Chametz: Paradoxical Approaches to the Chametz Prohibition

By Dan Rabinowitz

Some Pesach rituals trace their history for millennia. Others are of more recent vintage and continue to evolve significantly without any indication of stopping. Two in that category define the contours of chametz prohibition, one expanding and the other contracting its perimeters. Each’s creation was itself a radical departure from the status quo. In both instances, rabbis readily overcame established legal precedent. But their methodologies differ substantially and, at times, are contradictory. Yet, the intersection between the two, mechirat chametz and kitniyot, remains unexplored, and their conflicts unresolved.[1]

Mechirat Chametz

The present-day practice of “mechirat chametz” consists of the pre-Pesach transference of the title to the Jew’s chametz to a non-Jew, and upon the conclusion of Pesach, the chametz reverts to the Jew at no cost. The Torah prohibits any relationship between a Jew and their chametz on Pesach. Aside from the usual restrictions against eating or otherwise enjoying a prohibited item, here, the Torah proscribes even possession. One must destroy their chametz. The Mishna (Pesachim, 21a) and Talmud (Pesachim 13a) recognize that one can avoid liability if they sell their chametz to a non-Jew. But those transactions were permanent and irreversible, and the chametz never returned to the Jew. The first instance of a reversible transaction appears in the Tosefta (Pesachim 2:6).

ישראל ונכרי שהיו באין בספינה וחמץ ביד ישראל ה“ז מוכרו לנכרי ונותנו במתנה וחוזר ולוקח ממנו לאחר הפסח ובלבד שיתנו לו במתנה גמורה

A Jew and a non-Jew are boarding a ship on the eve of Pesach, and the Jew has chametz, he can gift it or sell it to the non-Jew and get it back afterward so long as it was an absolute gift.

The Jew is boarding a ship on Erev Pesach,[2] on a journey that will extend beyond the holiday. There is enough non-chametz for Pesach, but if he destroys his chametz now, he likely will not survive the remainder of the journey. Can one violate Pesach and keep the chametz? If the chametz is necessary to survive Pesach, he can keep it and even eat it on the holiday. But does a future pikuah nefesh issue justify violating the law now? According to the Tosefta, a reversible transaction will avoid liability for the chametz, so long as it is “matanah gemurah,” an unconditional gift, and not matanah ‘al meant le-hachzer. One can justify relying on pure legal formalism and comply with all the technical requirements of a transaction, even if the practical effect of this transaction is a nullity.

Another version of the Tosefta seems to envision an even more restrictive view of the transaction. In this version, in addition to the requirement that the transaction is a “matanah gemurah,” there is one more caveat, “u-belvad she-lo yarim,” “so long as it is not a trick.” [3]

According to Rav Amram Gaon (810-875) and Rishonim, “no trickery” codifies the implicit limitation of the Tosefta, that this solution is exceptional (expressed nautically) and can never become the norm. This approach remained the practice for hundreds of years, and there was no yearly mechirat chametz. The Rambam and the Rosh repeat the case described in the Tosefta, occurring on a ship, not in any other context. [4]

R. Yisrael Isserlein (1390-1460), in his collection Terumat HaDeshen, is the first recorded instance of a Jew seeking to avoid financial loss affirmatively engaging in the Tosefta’s solution. He discusses a case where someone owns a significant amount of chametz and would incur a loss if he destroys it. But there is a non-Jewish acquaintance that is willing to accept the chametz gift with the understanding that he will return it after Pesach. Isserlein permits this approach so long as it is a gift without explicit conditions. Isserlein does not limit the frequency of resorting to this approach.[5]

The immediate impact, and rate of adoption, of his decision, remains unclear. Indeed, some question the historicity of Isserlein’s responsa. They claim that the issues described are theoretical and are not in response to actual queries or events.

In the 16th century, R. Yosef Karo (1488-1575) discusses the legal issue of the retrievable sale in his commentary on the Tur, Bet Yosef, and records Isserlein’s ruling in Shulchan Orach but does not indicate whether it was commonplace. In his commentary on Shulchan Orach, R. Moshe Isserless (1530-1572) (Rema) is silent on this issue entirely and does not mention a yearly custom to sell chametz. The first to widely apply this technique and significantly lower the requirements was R. Yoel Sirkes (1561-1640).

With the introduction of propination laws in the 16th century and the rise of the arendtor, there was consolidation in the alcohol industry, shifting control from localized production by peasants to the ruling class. Many of those licenses were managed or leased to Jews. By the late 16th century, Jews in Poland and Lithuania were firmly entrenched in the alcohol industry. For many non-Jews, arendtor and Jew were synonymous. According to one account, Jews held a monopoly on the entire alcohol trade in Cracow. This created an issue for Pesach. While Isserlein and Karo, and many others accept that one can sell their chametz, they all explicitly require, like any standard transaction, that the non-Jew remove the chametz he bought. Karo, in Shulchan Orach, codifies the requirement that the chametz is “me-chutz le-bayit,” outside of the Jews’ control. The Jew’s house was chametz-free. But it was impractical to remove the distillers’ chametz from their property because of the substantial amounts and the fear that with alcohol, the non-Jew might not return it. [6]

Faced with these issues, Sirkes created a new approach to the sale. Mechirat chametz is not just chametz, he also counseled to sell the ground underneath the chametz. It effectively created non-Jewish property within the Jew’s home. The chametz was “me-chutz le-bayit,” but remained in situ.

Sirkes’ ingenious solution created another issue. When the sale was just for chametz (a transportable good), a monetary transaction, even a nominal one, sufficed. But a written contract is required to sell land to a non-Jew. Rather than change the process for the sale of chametz and mandate a written contract, Sirkes relaxed the contractual requirement. He reasoned that requiring a contract for mechirat chametz potentially created another economic issue. He explained that a written agreement might otherwise induce the non-Jew to think the Jew fully sold the chametz and might keep it! This would trigger significant losses, and Sirkes was willing to forego the contract entirely. He justifies both the sale and the diminution of its legal requirements because of potential economic harm.[7]

Sirkes’ solution generally relaxed the legal requirements, but he did add two new aspects to mechirat chametz. First, one must explicitly acknowledge the deficiency of the sale and announce that “I am selling you the room where the chametz is for money and even though I didn’t write a contract.” He explains that this formulation works according to Tur and R. Karo in Bet Yosef (Choshen Mishpat 194), even for a land sale. Left unmentioned is that Sirkes rejects that position in that same section.

Second, the Jew must give the non-Jew a key to the house. Without that, no external action signifies the chametz is not the Jews, and the sale is clearly a sham. By the early twentieth century, R. Yisrael Meir Kagan, in his Mishna Berurah, further eroded the key requirement and nullified the need for it entirely for all intents and purposes. Rather than a physical transfer of the key, the Mishna Berurah allows one merely to identify the key’s location. Like the chametz, the keys can remain in the Jew’s possession, on their regular hook, and in the Jew’s control. There is no independent source for this leniency. Instead, according to R. Kagan, it is “pashut.” [8]

The key requirement was not the only aspect of Sirkes’ formula that fell by the wayside. Almost immediately after Sirkes created his workaround, it was being degraded. Both R. Avraham Gombiner (1635-82), in his Magen Avraham, and R. David HaLevi Segal, in his Turei Zahav, hold that even giving a key is unnecessary. Simply setting aside a place for the chametz is enough. (Although it seems that the key’s association with mechirat chametz was so pervasive that people began to sell the key rather than the chametz.) [9]

Sirkes’ idea that one can include non-chametz items in the fictional sale was adopted in a different context, again because of the effect of the alcohol trade. At the time, most distilling occurred with rye. The process produced a significant amount of spent rye, while otherwise useless, could be turned into cattle feed. Jewish cattle farmers recognized that they needed to sell their animal feed, and they did so. But, without that feed, the animal’s health and well-being were affected, and it took them time to recover after Pesach. Thus, it became customary to sell not only the chametz but also the cow. Now the non-Jews could come and feed the now non-Jewish cattle their regular diet. While this was initially frowned upon by some, many ultimately accepted it. [10]

The Dispute in Jassy Regarding Modifications to the Process

Despite all of these changes, until the 19th century, one aspect of the sale remained consistent; the individual conducted it, and there was no public communal sale of everyone’s chametz. Yet, leaving it to the individual proved problematic. According to some, there were widespread issues of sales not conforming with the (then) acceptable formulations, inattention to the transaction details, and a general failure to consummate the sale. To accommodate those realities, another shift in the process occurred. The most conspicuous example of introducing the new approach occurred in Romania in the 1840s. R. Yosef Landau and R. Aaron Moshe Taub, two of the leading rabbis in the same city, Jassy, disagreed about the propriety of instituting this new method. Collectively, they published six titles and five books supporting their respective opinions.

Additionally, Landau asked one of the most well-known legal authorities in the region, R. Shlomo Kluger (1785-1869), to adjudicate the dispute. He wrote a lengthy teshuva siding with Landau’s approach. Yet, this remained unsettled in his mind, and some years later, he retracted his position and agreed with Tauber.

R. Yosef Landau (1791-1853) came from a rabbinic family and, in his youth, studied with R. Levi Yitzhak of Bardichiv. He married young, and when his first wife died at 18, he remarried. His father-in-law was wealthy and generously supported Landau, enabling him to study full-time. At 22, he accepted the position as Liytin’s rabbi. In 1834, at the suggestion of the Ruzhiner Rebbe, Landau took the position of chief rabbi of Jassy.

Jassy (Iași) is today located within northeastern Romania, near the border with Moldovia. In 1565, it became the capital of the former principality of Moldovia and today is the second-largest city in Romania. Jassy had long been the spiritual center for Jews throughout Romania/Moldovia. By the early 19th century, it became a hub for Chasidim. In 1808, R. Yehoshua Heschel Shor, the Apter Rebbe, settled in Jassy.

The early to mid-19th century was arguably the high point of Jewish life in Jassy. At the opening of the century, there were less than 2,000 Jews. By 1838, there were almost 30,000 Jews, accounting for over 40% of the total population. Concurrent with the influx of Jews into Jassy was a general improvement of its finances, especially after the Russian Turkish peace of Adrianople in 1829. Jews played a sizeable role in the city’s overall commerce. They held monopiles to several industries, cattle, cheese, cereals, and dominated in others, such as banking, and owned most commercial buildings in the center of town.

While progress had been good for Jassy, it came with challenges. The combination of the sprawling populace and robust commercial market created complexities that required a revision to the process. After Landau arrived in Jassy, he instituted a new form of mechirat chametz. He established a system where individuals would no longer transact directly with a non-Jew. A handful of select people would buy everyone else’s chametz, and those designated ones would execute the final sale to the non-Jew. Appointing a few knowledgeable people ensured consistency and greater compliance.

Sometime before 1842, Landau published the rationale for this decision. There are no extant copies of that book, Seyag le-Torah, and consequently, the publication date has confused some bibliographers. Friedberg, and after him, Vinograd, date Seyag le-Torah to 1846, which would place it at the tail end of the controversy, its final book, published after three years of silence. But Shmuel Ashkenazi demonstrated that Seyag le-Torah is the first book published regarding the communal mechirat chametz controversy in Jassy and was printed around 1842. The rest of our discussion follows Ashkenazi’s reconstruction of the dispute. [11]

By 1842 Landau could no longer lead the community alone. He requested for the Jewish community to hire a second rabbi. With Landau’s blessing, R. Aaron Moshe Tauber (1787-1852), originally from Lviv, was engaged. Tauber also came from a storied rabbinic family and was the grandson of R. Yoel Sirkes. He also married into a wealthy family in Przemysl, Poland, and studied there for a few years after marriage. He began a relationship with R. Yaakov Meshulum Orenstein (author of the Yeshuot Ya’akov), then rabbi in Jaroslaw, about ten miles from Przemysl. Tauber eventually left Przemysl and returned to Lviv. By this time, Orenstein was the chief rabbi of Lviv, and he and Tauber reconnected. Tauber also began regularly studying with R. Shlomo Kluger, then rabbi in Kulykiv, on the outskirts of Lviv. In 1817, Kluger would leave Kukykiv for Brody, but Tauber remained until 1820. When he was 32, he took a position in the hamlet of Snyatyn, Ukraine, over 150 miles south of Lviv. In 1831, he made an unsuccessful bid for the chief rabbi of Óbuda (one of the three towns that merged in 1873 to form Budapest). In 1842, after 24 years in Snyatyn, Tauber moved further south to Jassy as the new co-rabbi.

Soon after arriving, he learned of Landau’s mechirat chametz process and disapproved. In a public address, Tauber criticized the practice but declined to take any more concrete action against it because he deemed it an entrenched and accepted custom. Nonetheless, he counseled those “who have the fear and trembling of God in their heart” to execute a private sale. According to Tauber, Landau started a whisper campaign that all private sales of chametz are ineffective. Nonetheless, Tauber “remained silent” and held himself back from a direct conflict with Landau.

By Pesach of 1843, all the gloves were off. Tauber claimed that he identified additional issues with the new procedure that convinced him he must act; otherwise, all Jassy’s Jews risked liability. On the eve of Pesach 1843, he published Modo’ah Rabba (An Important Announcement), identifying issues with Landau’s approach to a communal mechirat chametz. Landau had his response ready and published Mishmeret Seyag le-Torah defending his position in Seyag le-Torah within a month. A second title, Bitul Modo’ah (A Nullification of the Announcement), specifically addressed the issues Tauber raised in Modo’ah Rabba appeared at the end of the book. While Landau was formulating and printing his response, Tauber was working to explain his position further.

A short time later, Tauber published Hagu Segim (Remove the Detritus, based upon Misheli 25:4), offering additional evidence against the new practice. But, he wrote this before seeing Landau’s Mishmeret Seyag le-Torah and did not discuss its arguments. To address that, soon after, Tauber published another pamphlet, Hareset Mishmeret (Destroying the Guardian), that attempted to rebut Landau’s rejoinder of Tauber’s rejoinder of Landau’s original defense.

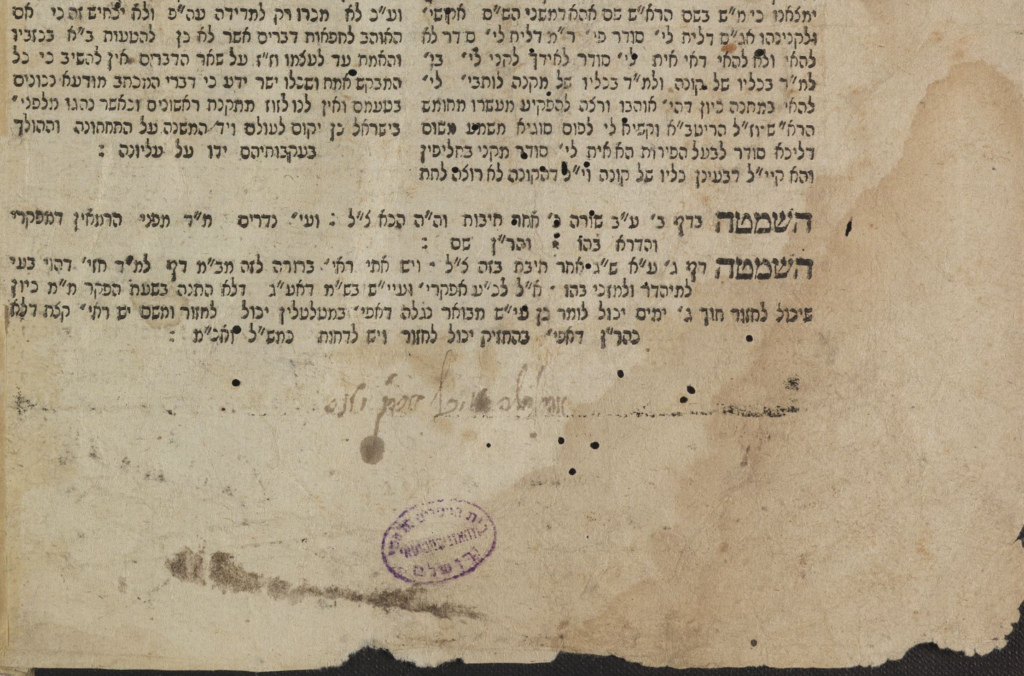

A few copies of Landau’s Mishmeret le-Seyag with Bitul Mo’dah and Tauber’s Hareset Mishmeret survive. There are no extant copies of the other books. Mishmeret le-Seyag/Bittul Mo’dah and Hareset Mishmeret are now available online. But both digital versions are flawed. The National Library of Israel’s copy of Hareset Mishmeret is damaged, and some text is lost. But Tauber autographed the final page of that copy.

The issue with the copy of Mishmeret le-Seyag le-Torah on Hebrewbooks.org is more significant. There is no title page, and the text begins on the first page. Typically, the verso of the title-page is blank or contains copyright information. This copy was originally reproduced by Copy Corner. In the pre-internet era, the Goldberg brothers photocopied rare and out of print books and bound them in a rudimentary hardcover and distributed them through Beigeleisen Books in Boro Park. Through their efforts thousands of seforim were accessible to the wider public at very reasonable prices. For those without access to libraries with significant seforim collections, Copy Corner’s catalog stepped in to address that gap. When Copy Corner photocopied the books they added their publication information to the verso of the title page. Normally not an issue, here it results in a blank page with just the Copy Corner legend substituted for the second page of the text of Mishmeret le-Seyag le-Torah.

Hareset Mishmeret was the last public missive, but the two sides remained at loggerheads privately. Communal leaders unsuccessfully pressed for a resolution but eventually, the two reconciled. Love instigated the cessation of hostilities.

In 1846, R. Landau’s son, Mattityahu, married Tauber’s daughter. But the marriage almost didn’t happen. Not because of the controversy over mechirat chametz. Instead, the bride’s and groom’s mothers shared the same name, Hindi. Some view such a match as taboo. But the Ruzhiner Rebbe, R. Yisrael Friedman, endorsed the match. He reasoned that there is no prohibition here because neither mother uses her given name. They both go by “Rebbetzin.” [12]

Sometime before the intermarriage of the two families, Landau requested R. Shlomo Kluger’s assistance to resolve the dispute and determine which approach to adopt. Kluger’s reply begins that he is personally unacquainted with R. Landau but that Tauber is a childhood friend. Despite that friendship, Kluger sides with Landau.

Tauber only recently arrived in Jassy, the largest city in Moldovia, and was unwise to the realities of a big city. Kluger attributes Tauber’s objections to his naivety. Tauber spent the last twenty-two as the rabbi of the small town of Sniatyn, where there were around 2,000 Jews compared to Jassy’s 30,000. The traditional practice of private transactions might work in a town the size of Sniatyn, where Tauber was able to supervise the process. Jassy was a different animal. Landau was responding to those realities when he restructured mechirat chametz. Kluger was the rabbi of Brody, a substantial city of an estimated 15,000 Jews, and saw first-hand the challenges of a large and more cosmopolitan community. Like Landau, Kluger adopted the revised mechirat chametz. Indeed, he had already done so six years earlier! Over the next seven printed double-column pages, Kluger justifies his and Landau’s mechirat chametz ritual, concludes that Landau’s approach is correct, and describes it as “takanah Gedolah,” a worthy edict. Kluger, however, notes that he finds the whole episode distasteful and that he doesn’t have time to engage in these sorts of controversies and communicates his mystification that such a vicious dispute could arise over a “davar katan” like this.

Despite Kluger’s comprehensive defense of the communal mechirat chametz ceremony, he ultimately regretted that position. Kluger included an addendum when this responsum went to press in 1851. After seeing the effects of the new approach, he explained that he was reversing his stance. With the consolidation of mechirat chametz into a communal sale, an industry arose. Profiteers saw an opportunity and began competing for people to sell them their chametz. With money as their only motive, they were incredibly sloppy with the sales. With the single points of failure, there was often no legally recognized transfer, leaving countless people owning chametz on Pesach. Kluger disavowed his lengthy defense. He ascribed it to alternative motives, preserving Landau’s honor. Kluger concluded with the recommendation that every individual execute their own contract with the non-Jew, i.e., Tauber’s position.[13]

During that same period, R. Moshe Sofer, in a very lengthy responsum, supports preserving the less than 100-year-old practice of selling chametz and rebuffing the many reasons it seemingly conflicts with established Jewish law. Despite his leading the rallying cry of “hadash assur min ha-Torah,” Sofer, who rejects new approaches because of their novelty, unqualifiedly approved of mechirat chametz.

R. Ephraim Zalman Margolis wrote to Sofer and raised issues with the current process as it was nothing more than “ha-aramah” and that certainly selling one’s animal is prohibited. Sofer began by noting that there are instances where ha-aramah is permitted. Hazal crafted those exceptions because they recognized that “אין כל המקומות והזמנים שוים.” Ultimately, he concluded that despite the sham nature of the modern procedure, it is a fully-realized transaction that discharges ownership for purposes of chametz and even permits the Jew to sell their cattle with the chametz. [14]

Sometime after the widespread adoption of communal mechirat chametz, there was another revision to the practice. Now, the individual no longer sells his chametz to the rabbi and the individual never directly executes a sale. Instead, the individual approaches the rabbi not to sell him the chametz but appoint him an agent to sell it on their behalf.[15]

The most recent shift in mechirat chametz is that it is no longer de facto but de jure. According to some, R. Shlomo Yosef Eliashiv among them, today, mechirat chametz is obligatory even if one destroyed their chametz. [16]

(Bardak, recently satirized the contemporary practice, with all its details, in an episode that imagined a very sophisticated purchaser that presses their rights, legal and political.)

Kitniyot

The historical approach to mechirat chametz and the willingness to adapt biblical law to the realities of modern society stands in sharp contrast to another chametz-related issue, kitniyot. There is no doubt that the biblical prohibition against chametz did not include kitniyot. The Mishna and Talmud agree that it is permissible. At best, it is an Ashkenazi custom and/or edict whose earliest record is the 13th century and was never universally adopted by all Jews. Consequently, many rabbis explicitly rejected the prohibition as either a “minhag ta’ot” or even a “minhag shetut.” Yet, according to some, kitniyot is such a powerful legal concept that even in instances of severe famine, kitniyot remains prohibited. Kitniyot is even more pervasive now than ever before, with new items added yearly to the list. [17]

There have been attempts to repeal kitniyot custom since the 18th century, without significant success. In the case of the nascent Reform Judaism movement, like many other laws and customs, it overturned kitniyot without any specific halakhic justification. But the other attempts came with substantial legal analysis that supported removing the prohibition. Many raised economic arguments to justify reversing kitniyot. In the case of mechirat chametz, the initial beneficiaries of the sale were well-to-do Jews who held large amounts of chametz. The kitniyot restrictions mainly affected the poor who could not afford expensive matza and for whom kitniyot’s low cost would provide a more economically feasible alternative to satisfy their daily caloric needs.

R. Tzvi Ashkenazi, Chakham Tzvi (1656-1718), one of the leading rabbis in Western Europe, first articulated this argument. Chakham Tzvi concluded that the economic harm justifies removing the restriction. Nonetheless, he declined to act alone, and without others joining his approach, the rule remained in effect even in the communities he served. Likewise, his son, R. Yaakov Emden (1697-1776), agreed with removing the restriction against kitniyot but required consensus among rabbis to make any practical change. [18]

Eventually, beginning at the turn of the 19th century, a handful of communities in Western Europe acted upon the approach of Hakham Tzvi (in addition to marshaling other arguments) and abolished the prohibition against kitniyot.[19] The first to do so was a community under French control, the Consistory of Kingdom of Westphalia, created by Napoleon in 1807, today located in the north-western corner of Germany. The argument for the repeal was initially only on behalf of garrisoned soldiers in the area. They did not have access to large amounts of matzo, and permitting kitniyot would alleviate their hunger. Ultimately, the kitniyot repeal applied to all Jews in the area. Perhaps the most well-known rabbi involved, R. Menahem Mendel Steinhardt, authored a lengthy defense of the dispensation and many other changes and sent it to his close friend R. Wolf Heidenheim (1757-1832). Although Steinhardt specifically told Heidenheim to keep the letter private, Heidenheim believed that the analysis was too compelling to hold back from the public. Heidenheim went ahead and published it without consent at his own expense. He also appended some of his notes to the book. The book, Divrei Iggeret, published in 1812, contains one of the most cogent published arguments for the abolition of kitniyot. Nonetheless, Steinhardt’s defense was rejected by many.

Despite those rejections, in addition to Heidenheim, others continued to support him, if not his kitniyot position. His former havruta, R. Betzalel of Ronsburg (1760-1820), who provided a haskamah to Steinhardt’s responsa work, Divrei Menahem, still held him in high esteem long after Divrei Iggeret. He also secured two subsequent rabbinic positions in other Jewish communities. Others, however, cast him as a villain.

One recent book characterizes Steinhardt and others as “the wicked maskilim may their names be blotted out” and ascribes their motivations as solely driven “to disparage the kadmonim.” Rather than concern for the poor, according to the book, the true purpose of reversing the prohibition against kitniyot is to permit chametz on Pesach eventually. [20]

Heidenheim’s support troubled some because he is an accepted orthodox figure. One approach is to attribute Heideheim’s willingness to publish Divrei Iggeret as a favor to Steindhardt’s uncle, R. Yosef Steinhardt, with whom Heidenheim studied in his teens.[21] This explanation seems implausible. First, this approach ignores Heidenheim’s unreserved praise of the force of Menahem’s arguments. Heidenheim justified his decision to unilaterally publish Menahem’s letter so that “every honest, sensitive, and intelligent person will see that [Menahem’s] purpose is to teach Beni Yehuda avodat Hashem, to fear and love Him in the ways of truth and peace . . . and to respond to the detractors and support the poor and provide them as much food as possible.” Second, when Divrei Iggeret was published, Yosef Steinhardt had been dead thirty-six years, and when he passed, his nephew, Menachem, was only seven years old. Indeed, another author, Benyamin Shlomo Hamburger, highlights this lack of connection between uncle and nephew to diminish any family prestige that might inure to Menachem.

Likewise, Hamburger turns Menachem’s adoption of his uncle’s surname (and not the more traditional approach of using his birthplace, Hainesport, as the surname) into a liability. Hamburger sees this as a blatant example of carpetbagging, trading on his uncle’s reputation. Similarly, Hamburger delegitimates Menachem’s responsa work, Divrei Menachem, and describes it as entirely self-interested, simply “an attempt to get any rabbinic position.”

Although Steinhardt’s approach to kitniyot did not significantly alter the orthodox practice, he substantially changed Jewish liturgical practices despite attempts to marginalize him. Steinhardt’s Divrei Iggeret comprises ten letters, one of which is devoted to kitniyot. The other nine argued for changes to other Jewish practices. The seventh letter addresses the custom to recite the mourner’s Kaddish.

Until the 19th century, the accepted Ashkenazi custom was to have each mourner recite the Kaddish individually. Steinhardt argued for adopting the Sefardic tradition of all the mourners reciting Kaddish in unison. While some rejected that position as a change to the status quo, including R. Moshe Sofer, Steinhardt’s modification of the practice is today widely accepted. His opinion was first cited approvingly in the commentary to Shulchan Orach, Piskei Teshuva, with the instruction to review Divrei Iggeret for its compelling arguments. Many of those arguments mirror those Steinhardt relied upon for his repeal of kitniyot. Among those that kitniyot lacks Talmudic sources, the current restriction did more harm than good, the Sefardim already do it, and R. Emden theoretically permits its annulment.

Steinhardt first categorizes the entire kaddish ritual as a custom that “has absolutely no root or foundation.” He challenges any attempt to find early sources that support incorporating Kaddish into the standard prayers. Neither the Bavli nor Yerushalmi nor the “Rishonim” incorporate the practice. Steinhardt dismisses midrashic sources, presumably the Zohar Hadash (Achrei Mot, 112), as irrelevant to determining practice. Second, the current custom of assigning only one mourner to right to lead Kaddish is detrimental because it leads to fighting for priority and a general lack of decorum. Third, the modification is the standard practice amongst Sefardim. Fourth, in theory, R. Yaakov Emden’s willingness to overturn the Ashkenazi custom in favor of the Sefardic one. Fourth, he cites R. Moshe Hagiz’s that implies reciting kaddish unison is permitted. He concludes that despite canceling the historical practice, his position is also ancient.[23]

Steinhardt’s change was embraced by conventional rabbis, explicitly citing the Divrei Iggeret and incorporating the change into their codifications. For example, Kitzur Shulchan Orach, Ta’amei Minhagim, Kol Bo’ al Avelut, and the more recent Peni Barukh associate the change with Divrei Iggeret. R. Gavriel Zinner, in his work on the laws of mourning, Neta Gavriel, didn’t just cite the Divrei Iggeret; he reproduces the entire letter from “ha-Gaon Rebbi Mendel Steinhardt.”[24]

Hamburger is again troubled by the seeming approval of Menahem’s modification of Kaddish and asks, “how is it possible that Divrei Iggeret received such a positive reception that he became the source of this [new] law?” The answer: Steinhardt hoodwinked the Eastern European rabbis. They thought that the change occurred with the consent of all the German rabbis and was unaware that Menahem acted alone and his true purpose was radical reform. Left unexplained is why many of the same Eastern European rabbis were aware of his actual intentions when it came to kitniyot.[25]

Likewise, many of those same personalities that vigorously defended the retention and extension of the leniency of mechirat chametz refused to budge on the custom of kitniyot. Despite the lack of supporting evidence, R. Moshe Sofer held that repealing the kitniyot restriction is impossible because it is a universally accepted formal edict. Nonetheless, among his arguments in defense of mechirat chametz was that “any restriction that the Talmud does not explicitly mention we cannot decree that is prohibited.” [26]

R. Tzvi Hirsh Chajes defends the practice of mechirat chametz. He accepted that the justification for mechirat chametz is economic. Nonetheless, he rejects the elimination of kitniyot as a too substantial reformation of Jewish practice to allow, even though it too caused significant financial hardship. According to him, because the Reform movement abolished kitniyot, any other attempt is tainted and assumed to be driven by the same anti-Orthodox sentiments and must be rejected to maintain the status quo. Even though the first major successful attempt to remove kitniyot was not a Reform congregation but an Orthodox one, headed by notable Orthodox rabbis, who based their decision on the law. [27]

The practice of mechirat chametz significantly altered the landscape of Pesach compliance. Each stage of its evolution required creative solutions to contemporary issues as they arose. Rather than invoking the general rule that chametz demands a strict reading of the law, leniencies were repeatedly devised and were near-universally adopted. Indeed, R. Isserlein, in his responsum permitting mechirat chametz, rejects that principle’s applicability to mechirat chametz. With limited exception, until the 17th century, Jews complied with the straightforward reading of the Biblical restriction, “chametz shall not be found in your houses.” The changing economics of the 17th century forced the rabbis to confront a new reality where it was no longer financially possible to physically remove one’s chametz. One rabbi’s solution was universally adopted, altering the mechirat “chametz” to include a second sale, that of the land. In less than a century, his formulation proved insufficient to deal with the continuing changing reality. Other Rabbis instituted additional modifications to the process. Now there is no direct sale of chametz, and the mechirat chametz ritual consists of appointing an agent. Each of these changes required reliance on leniencies, and in nearly every instance, the modifications themselves created ancillary issues. Ultimately, rabbis overcame all the objections, and the mechirat chametz ceremony remains in full effect.[28]

Paradoxically, kitniyot, despite the many reasons marshaled against retaining the practice, each of these is ruled insufficient to justify repealing kitniyot. Instead, the principle of “the severity of the prohibition of chametz (leavened food) mandates rejecting leniencies” was applied to kitniyot (non-leavening foods) to justify its endless expansion and ignored for mechirat “chametz.” As of now, mechirat chametz does not apply to kitniyot, and the two practices remain isolated from one another, just as they have in their development and legal approach. Both, however, remain examples of the dynamic nature of Jewish practice even within Orthodoxy.

NOTES

[1] This article is not intended to provide a comprehensive survey of all the literature regarding mechirat chametz and kitniyot. The focus of the article is the historical modifications to the practices. For a general discussion regarding the history and application of mechirat chametz, see Shmuel Eliezer Stern, Mechirat Hametz ke-Hilkhato (Bene Brak: 1989); R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin, Ha-Mo’adim be-Halakha, vol. 2 (Jerusalem: Talmud HaYisraeli HaShalem, 1980), 294-304; Tuvia Friend, Mo’adim le-Simha, vol. 4 (Jerusalem: Otzar haPoskim, 2004), 151-223.

For a comprehensive discussion regarding kitniyot, see the recently published book by Yosef Ben Lulu, Kitniyot be-Pesach: Gilgulo ve-Hetatputhoto ha-Halakhtit ve-Historiyt shel Minhag Zeh be-Adat Yisrael ’ad Yamenu (Be’er Sheva: Dani Sefarim, 2021); see also our discussion, “Kitniyot and Stimulants: Coffee and Marijuana on Passover,” Seforim blog, March 9, 2010.

[2] The scenario of boarding on the eve of Pesach is problematic. The Tosefta prohibits boarding a ship within three days of Shabbat. Tosefta Shabbat 13:13. He is already in breach of one prohibition confirms that this is an extraordinary case.

[3] This is an alternative text and not a later interpolation. See Leiberman, Tosefta ke-Peshuto, Seder Mo’ad, vol. 4 (New York: JTS, 2002), 495-96. But R. Yosef Karo mistook this just to be the commentary of the BaHaG and not part of the text because otherwise, it would prohibit the then-current form of mechirat chametz. Karo dismissed “shelo yarim” as an independent requirement and treated it as simply a reiteration of the prohibition against an explicitly conditional gift. See R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin, Ha-Mo’adim be-Halakha, vol. 2 (Jerusalem: Talmud HaYisraeli HaShalem, 1980), 295.

[4] See Lieberman, id. at 496, collecting sources.

[5] See R. Israel Isserlein, Shmuel Avitan ed., Terumat ha-Deshen (Jerusalem: 1991), no. 120, 93. Of note is that Isserlein does explicitly cite the Tosefta as his source. Indeed, his “rayah” “prooftext” is a passage from Talmud Bavli (Gitten 20b). He argues that the Talmudic source generally recognizes a transaction even when the parties’ intent is for the recipient to return it. It is possible that he held the Tosfeta alone is insufficient justification for the broad applicability of a reversible gift. Instead, he needed to prove the general efficacy of this type of transaction.

[6] Gershon Hundert, Jews in Poland-Lithuania in the Eighteenth Century (Berkley: University of California Press, 2004), 14-15, 36-37; see generally, YIVO Encyclopedia, Tavernkeepers; Glenn Dynner, Yankel’s Tavern: Jews, Liquor, & Life in the Kingdom of Poland (Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 2013). Jews’ association with the liquor trade persists today in Poland. Since the 1980s, Kosher and “Jewish style” vodka has become popular with Poles. These vodkas are considered premium brands, allegedly so pure as to stave off any ill effects the next morning. See Andrew Ingall, “Making a Tsimes, Distilling a Performance: Vodka and Jewish Culture in Poland Today,” Gastronomica, 3 (1), (2003), 22-27.

[7] Sirkes assumes that a written contract is unnecessary. The contemporary practice of executing a written agreement occurred later. See Mechirat Chametz ke-Helkhato, 68-9.

[8] For a survey of sources requiring giving the key, see Mechirat Chametz ke-Hilkhato, 13n18. Mishna Berurah, 448:12 & Sha’arei Tzyion, id. He asserts that this position is alluded to in the Hemed Moshe. But the Hemed Moshe (448:6) discusses an instance where the non-Jew decides to return the keys to the Jew unilaterally. In that instance, the Jew does not violate the law. But this scenario still contemplates the Jew physically transferring the key to the non-Jew. There is no indication that the Jew can forego the entire transaction by simply referencing the existence of a key.

R. Yechiel Epstein (Arukh ha-Shulchan 448) also rules that the mere identification of the key’s location is sufficient to avoid liability. He also holds that he need not go alone if the non-Jew uses the key to access the room, not for chametz but to get something else. The Jew is permitted to accompany him to ensure the integrity of the goods.

[9] See Mechirat Chametz Ke-Hilkahto, 13.

[10] For an exhaustive collection of sources, see R. Yitzhak Eliezer Jacob’s 2003 book, Tevu’at be-Ko’ah Shor, devoted to the topic; see also Mehirat Hametz ke-Hilkhato, 30-31.

[11] See Yisrael Landau’s son, Mattityahu Landau, wrote a biography of his father. Toldot Yosef, (Bardichiv, 1908), 13-16; Shmuel Ashkenazi, “Ha-Mahloket bein Rabanei Yus be-Shenat 1843,” Ali Sefer, 4 (June 1977), 174-77. Iasi, Yivo Encyclopedia; Iasi, Pinkas Kehilot Romania.

For biographical information for Tauber, see Hayyim Nasson Dembitzer, Kelilat Yofei (Cracow, 1888), 151n1.

[12] Landau, Toldot Yosef, 15.

[13] Shlomo Kluger, Shu” T meha-Gaon Mofes ha-Dor R. Shlomo Kluger, in David Shlomo Eibsheuctz, Na’ot Desha (Lemberg: 1851) 3a-6b (at the back of the book). Avraham Binyamin Kluger, Shlomo Kluger’s son, published the book.

A few years later, another Pesach controversy, machine-made matza, also involved R. Shlomo Kluger. He was against using the new technology for Pesach. See Meir Hildesheimer and Yehoshua Lieberman, “The Controversy Surrounding Machine-made Matzot: Halakhic, Social, and Economic Repercussions,” Hebrew Union College Annual 75 (2004), 193-26.

[14] Shu’T Hatam Sofer, OH, 62.

[15] Like the other solutions, using an agent created its issues. But none were significant enough to undermine the efficacy or acceptance of the practice. See Mechirat Chametz ke-Hilkhato, 5-6, 110-19.

[16] See Mechirat Chametz ke-Hilkhato, 7. The legitimacy of the sale is of such force that even if someone completely ignores it and continues to eat and use their chametz, the sale is still effective for anything that remains. See R. Moshe Feinstein, Iggerot Moshe, Orach Hayim 1 (New York: 1959), 203 (no. 149).

[17] Ben Lulu, Kitniyot, 31-93.

[18] Yaakov Emden, Mor u-Ketiah, 453.

[19] Another early attempt to rescind kitniyot was the inclusion of a responsum in Besamim Rosh that alleges kitniyot source is from the Karaites. There is no basis for this assertion. On the contrary, the extant evidence demonstrates that Karaites affirmatively rejected any prohibition against kitniyot. See Ben Lulu, Kitniyot,173-75. See here for our previous discussions regarding the Besamim Rosh.

[20] Moadim LeSimcha 241-42

[21] See R. Nosson David Rabinowich, “Be-Mabat le-Ahor: Kamma he-Orot be-Inyan “Heter” Achilat Kitniyot be-Pesach,” Kovetz Etz Chaim 15(2011), pp. 345–348.

[22] Binyamin Shlomo Hamberger, Ha-Yeshiva ha-Ramah be-Feyorda: Ir Torah be-Dorom Germaniyah ve-Geon’eha (Bene Brak: Machon Moreshet Ashkenaz, 2010), 398-422.

[23] See Divrei Iggeret, no. 7, 10b-11a; Tzvi Hirsch Eisenstadt, Piskei Teshuva, Yoreh De’ah, 376:6.

[24] Gavriel Zinner, Neta Gavriel: Helkhot Avelut (Jerusalem: Congregation Nitei Gavriel, 2001), 344n2.

[25] Hamburger, Ha-Yeshiva, 412-417.

[26] For a discussion of R. Moshe Sofer’s position regarding kitniyot and his involvement in the controversy, see Ben Lulu, Kitniyot, 185-88.

[27] See Darkei ha-Hora’ah, chap. 2, Kol Kitvei MaHaRiTz, vol. 1, 223-225; Minhat Kenot, Kol Kitvei MaHaRiTz Hiyut, vol. 2, 975-1031.

[28] Some refrain from selling certain forms of chametz out of an abundance of caution, but the custom of the vast majority of Jews is to sell all types of chametz. See Mehirat Chametz, 5-6.