The Image of the Menorah in the Early Printed Hebrew Book

The Image of the Menorah in the Early Printed Hebrew Book

By Dan Rabinowitz

The menorah is one of the most recognizable Jewish symbols. Today it has been adopted by the State of Israel as her official symbol, and throughout history there are numerous examples of its use. Coins, headstones, paintings and synagogue walls etchings, lamps, mosaics, manuscripts, and books, all provide examples of the widespread usage and mediums. Many of these examples have been addressed by scholars, but there is a lacuna regarding the depiction of the menorah in the Hebrew book.[1]

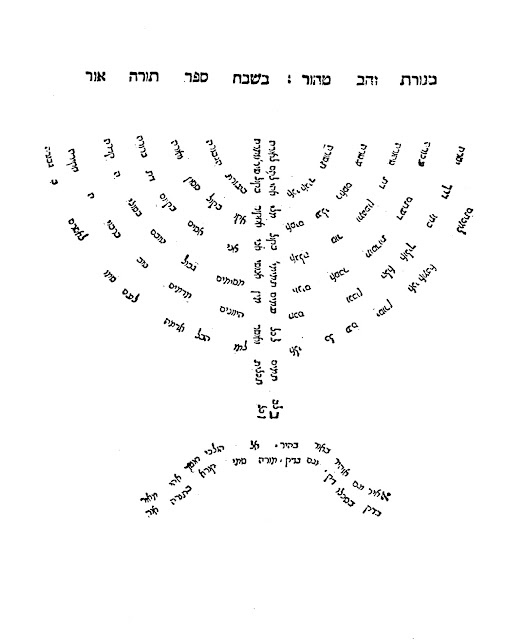

Despite that it is one of the most recognizable and ubiquitous symbols, the image of the menorah barely makes an appearance on Hebrew books. The first appearance of the menorah in a Hebrew book was Yosef Yikhya’s, Torah Or, Bologna, 1538. There is appears on the verso of the titlepage. The menorah is created via micrography and extols the value of the work. The designer even correctly places the menorah on a stand (and not a solid base as shown in the Arch of Titus). [2]

From the inception of printing, Hebrew printers, like others, created and populated their works with their unique marks. These symbols served advertising for the publisher. Perhaps the only other symbol with such wide resonance and connection to the Jews as the Menorah is the star of David. There are over 200 printers’ marks, or emblems, close to 20 examples of the Magen David, and multiple appearances of other Jewish symbols, lions, David, Solomon, eagles, but two only of a menorah. [3]

Meir ben Jacob Parenzo, (aka Parentio, Parintz, or Maggius Parentinus), operated in Venice from 1545 until his death in 1575. He apprenticed in Daniel Bomberg’s printing shop, and in 1545 he began working for the Venetian printer, Cornelio Adelkind. Although most of his career was in the service of others, he did publish a handful of books on his own. He did not own a press and likely used Bomberg’s Press. All of these books bear Parenzo’s printers mark, a menorah. Whatever ambiguity there is about his surname, his personal name, Meir, alludes to lighting, thus a natural connection to the menorah. On either side of the menorah, “This is Meir’s menorah, he is the son of Yaakov Parenzo.”

Parnezo’s mark comprises around half of the title page. This grotesque design was called out for being unique among his contemporaries, but that it was “a pathetic bid for immortality.” As a measure of divine justice, according one scholar of Hebrew Italian printing, that “Meir Parenzo, notwithstanding his hope for immortality, is completely forgotten except for a small circle of Hebrew bibliographers, who, although conscious that the individual contributions of the men they commemorate are negligible in the great current of human affairs as it flows majestically down through the ages, nevertheless handing down (or transmitting) the knowledge of the existence of so many faithful men who have contributed their share to the enlightenment of the world.” [4]

Another printer, also a Meir, incorporated the menorah into his mark, although on a much smaller scale. Meir ben Yaakob Ibn Ya’ir, here too, the surname, Ibn Ya’ir, references light. The menorah appears inside a border, flanked by olive trees surrounded by four verses, all mentioning either oil or light. Meir was active between 1552 and 1555. He published a few books abridged books on the laws of shehitah, as well as a work on Hebrew grammar, all exceedingly rare. [5]

The menorah next makes an appearance in Moshe Cordovero’s, (1522-1570), first book, Pardes Rimonim. This illustration is not of the biblical menorah, rather it is a kabbalistic representation of the sefirot overlaid on the menorah frame. This illustration was printed in most subsequent editions of Pardes Rimonim, although not as an exact reprint of the first edition.

The first illustration of the menorah that was an attempt to depict and elucidate complexities of the biblical menorah only occurred in 1593. There were two books that include the illustration, Biurim and Omek Halakha.

R. Yaakov ben Shmuel Bunim Koppelman, (1555-1594) studied with R. Mordechai Jaffe, author of the Levush. In addition to traditional subjects, he was also well-versed in (my astronomy and mathematics. He published Omek Halakha in Cracow, 1593, a commentary on the Talmud. This slim volume of just 95 pages, is rich in illustrations, which appear on nearly every page. For example, there is a thirteen page an in-depth discussion of astrology with two full page diagrams of the lunar paths and many of the other pages include multiple illustrations. Koppelman includes a detailed diagram of the menorah with an accompanying commentary. [6]

The Biurim on Rashi was published in 1593 in Venice and attributed to R. Nathan Shapira. Shapira had died in 1577; his work includes three illustrations, the menorah, a map of Israel, and a diagram of how the spies carried the large bunch of grapes. This is the first Hebrew book to contain a map.

The book is one of the handful of examples of literary forgeries in Hebrew books. R. Shapira’s son, Yitzhak, published his father’s comments on Rashi in 1597 in a work titled Imrei Shefer. In the introduction he explains why there are two books that are attributed to his father on the same topic published within a few years of one another.

ואתם קדושי עליון אל תתמהו על החפץ שזה שתנים ימים יצא בדפוס איזה ביאורים הנקראים על שם הגאון אדוני אבי ז”ל, כי המציאוהו אנשים, אנשי בלי עול מלכות שמים, חיבור אשר מצאו, ומי יודע המחבר אם נער כתבו ורצו לתלותו באילן גדול אדני אבי ז”ל, חלילה לפה קדוש להוציא מפיו דברים אשר אין בהם ממש, כי הכל תוהו ובוהו ומזויף מתוכו, כלו עלו קמשונים כסו פניו חרולים. וכאשר הגיעו הספרים ההם בגלילות אלו הכרוז בהסכמת כל רבני ורשאי המדינות שלא ומכרו ויהיו בבל יראה ובבבל ימצא בכל ארצות אלו. ואשר קנו מהם יחזר להם המעות ולא ימצא בביתך עולה

[“Do not wonder why I am publishing what was published just two years ago, the Biurim, in my father’s name. As wicked people, people who found a book, a book which may have been written by a child. However, they wanted to use my father’s good name to publish their work. But, my father would never say such stupidities which appear in that book, their book is worthless and a forgery. When this was discovered all the Rabbis agreed that this book [Biurim] should be under a ban, no one should be allowed to keep it. Whomever purchased it should have their money returned, they should not allow a stumbling block into their home.”]

According to R. Shapiro’s son, the Biurim, is illicitly associated with his father. His son was not the only one to question the authenticity of the Biurim. R. Yissachar Bear Ellenburg in his Be’er Sheva and in his Tzedah L’Derekh states unequivocally that R. Shapiro did not write the Biurim.

The diagram of the menorah does not appear in Imrei Shefer. [7]

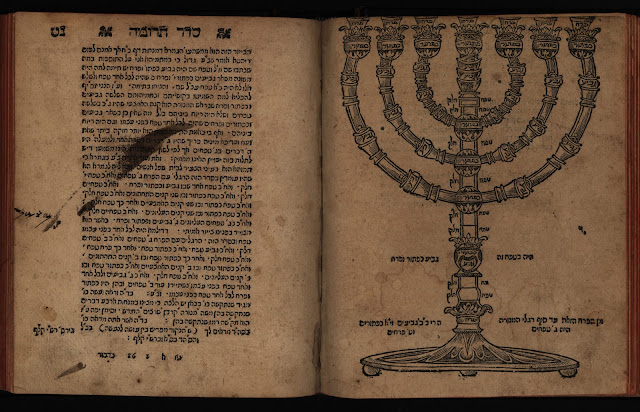

The diagram of the menorah appears in Yosef Da’at printed in Prague in 1609 by Rabbi Yosef ben Issachar Miklish (1580 -1654). He was a student of the Maharal of Prague and of Rabbi Ephraim Lonchitz, the author of the Klai Yakar. The purpose of the book was to correct errors in Rashi’s commentary. He used a 14th century manuscript to make those corrections. To better facilitate studying Rashi, the book includes illustrations including the menorah. This a full page with detailed descriptions of each part of the menorah. Interestingly, the base seems to combine two different approaches, one that has three legs and the other with a solid base. Miklish reproduces a solid base on top of three legs.

In 1656/57 Yalkut Shimoni with the commentary of Berit Avraham was published in Livorno, Italy. This one includes a menorah created via micrography, but unlike the others that appear at the front of the books, this one appears at the end. It is a colophon.

A unique example of the menorah appears in the 1684 edition of the Humash. It is the sole illustration on the title page. When the menorah appears on the title page, it is almost always in conjunction with other vessels or other symbols. This is perhaps the only instance of a stand-alone menorah on a title page.

The next appearance is the first time it illustrated a titlepage, in R. Shabbati ben Joseph Meshorer Bass’s (1641-1718), most well-known work, his commentary on Rashi, Siftei Hakhamim. This edition was published in Dyhernfurth, Germany at Bass’s press. This was the second edition of the work, (the first was published in 1680 in Amsterdam), and includes one of the most unusual Hebrew titlepages.

The titlepage depicts Moshe and Aaron, with the ark and other temple vessels, and prominently, and occupying the bottom third of the page, a menorah. Bass makes multiple luminary allusions on the title page. This edition includes

“.עם תרגום אנקלוס וביאור מאור הגדול רש״י ז״ל: ועליו מפרשי דבריו ככוכבים יזהירו: ובש״בעה נרות יאירו”

The menorah makes another appearance on the next page. Like the Torah Or, Bass uses micrography, in praise of the book, to form the shape of the menorah.

Aside from the figurative arts there was also a musical component to the page. This is not surprising as Shabbati was a musician and singer, and a noted bassist singer, hence the “Meshorrer”/“Bass” surname. On the bottom of the page, in the left corner, appears “Az Yashir Moshe” the beginning of the one of the fundamental Jewish musical pieces, and musical notes appear at the bottom of the page, in what appears to be a composition of sorts. This is one of the few times musical notations appears in early Hebrew religious books. Another is Immanuel Hayi Ricci’s commentary on the Mishna, Hon Ashir, printed in Amsterdam in 1731. Appended to the end of the book are three songs, two set to music with notation.

Another menorah appears in Bass’s edition. On the next page, like the Torah Or, the menorah is comprised of micrography extoling this edition with the commentary. [8]

In 1694, R. Avraham Tzahalon published a portion of his grandfather’s, R. Yom Tov Tzahalon’s (c. 1559-1638), responsa. R. Yom Tov was a child prodigy, only eighteen when he published his first work. That same year he was included in granting an approbation alongside R. Moshe Tarani (Mahrit) and R. Moshe Alschech. R. Yom Tov was no shrinking violet. And he had a dim view of R. Yosef Karo’s Shulhan Arukh. He belittled it, calling it only fit for children. The title page and the verso of the 1694 edition include depictions of the temple vessels and specifically the menorah. But his responsa do not discuss the temple vessels and this was included, “to beautify and embellish the title page of the book in a manner fit for print; the students illustrated holy concepts, the form of the Tabernacle and the Third Temple.” A rare of example of acknowledging the aesthetic beauty in the Hebrew book.

Three years later, the Italian scholar, Moshe Hafetz, (1663-1711), (aka Moses Gentili) published Hannukat ha-Bayit which discusses the Temple in great detail and includes numerous illustrations. Because of the illustrations, the book was printed in two parts. First all the text was printed with space left for the illustrations and illustrations were then added using etched copperplates.

His other work, Melekhet Mahshevet, includes his portrait, the first rabbinic portrait included in a Hebrew book, which is somewhat controversial because he is bareheaded. In a 19th century edition, a yarmulke was drawn on his head.[9]

The Bass titlepage served as the model for another lavishly illustrated titlepage. Although it served as a model, it was only a model and not a perfect facsimile. This was intentional. In this instance, the Menorah was the most important visual element of the titlepage and therefore is significantly larger than before and is in the center not the bottom of the page. Of course, this is because the book’s title includes menorah, Menorat haMeor. The book’s structure is based upon the biblical menorah and divided into seven parts, like the seven branches of the menorah. The title page was likely executed by the well-known engraver, Avraham ben Jacob, whose lavishly illustrated 1695 edition of the Haggadah, remains among the most remarkable illustrated haggadot and served as a model for dozens of other illustrated haggadot. Like in the Biruim, Jacob also produced a map, this one much more refined than the basic one in the Biruim. It is a large fold-out map of the Jews travels from Egypt to Israel. Most of his illustrations are copied from the Mathis Maren, a Christian, whose biblical illustrations were very popular. [10]

The illustration was reused by another Amsterdam printer, Solomon Proops, in 1723. Thus, this is one of the few instances of Hebrew titlepage images reflecting the title or the work itself rather than serving a mere ornamental purpose. The titlepage imagery was reused for a 1755 edition of the Torah. This time the menorah is significantly reduced in size.

While these menorahs depicted in Hebrew books, might differ in small details, they are consistent in depicting curved, and not straight, arm. Nearly every manuscript and all the archeological finds similarly depict the curved branches. Of late, this is subject to controversy. The Lubavitcher Rebbe heavily promoted his position that the arms of the biblical menorah were straight and not rounded. In the main, he based this on a manuscript in the Rambam’s hand that includes a depiction of the menorah with straight arms and the confirming testimony of his son that, according to Rambam, the arms were straight. This produced one of the more unusual exchanges in a haredi journal, in his instance, Or Yisrael, published in Monsey, New York. Those historic and documentary materials are used by R. Yisrael Yehuda Yakob, from Kollel Belz, as evidence against the Rebbe’s position. The article uses the mosaics in the 7th century Shalom al Yisrael Synagogue. The menorah is at the center of a large mosaic. The inscription near the mosaic indicates that the entire congregation, men, women, old and young, all took part in the creation of the mosaic. The Burnt House in Jerusalem’s Old City, that dates to the Second Temple period. Yakob then moves on to numismatic, citing a coin from the Hasmanoim period. Section three is then devoted to a discussion of the menorah on the Arch of Titus. Yakob references unidentified “hokrim” who posit that the base of the menorah was broken en route to Rome and was replaced with a base of a Roman creation. This explains why the base does not conform with the Rabbinic description and contains bas reliefs of various mythical and real animals. It was not the true one. Although unidentified, this position is that of the former Chief Rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Herzog as well as the nineteenth-century British Protestant academic, William Knight. Only in section four does Yakob turn to the more traditional Medieval Jewish commentaries. Ultimately, Yakob concludes that the rounded arms is the correct depictions and “justifies” the custom to draw it that way. Following the text, is a reproduction of the menorah from the second century synagogue, Dura Europas. A most unusual conclusion for a rabbinic article. (The image of the Dura Europos menorah actually depicts a straight arm menorah, that follows the Rebbe’s opinion. This is one of the only archeological examples of a straight arm menorah. The value of this image, however, is questionable. The menorah appears four times at Dura Europos. The straight arm one appears at the upper left corner of the opening for entrance. But, in the panel that specifically depicts the Mishkan and its vessels, there is a rounded arm menorah. While we don’t know what to attribute the differences to, it is more likely that greater care was placed in the accurate reproduction of the menorah within the context of the mishkan rather than were it serves as mere decoration.)

As would be expected, there was a rebuttal article that is more in line with the Haredi approach. The author concedes that his main objection is to Yakob’s approach, the “fundamental point which is almost litmus test of one’s religiosity: any evidence adduced from pictures and archeological evidence, God forbid, to rely upon these things or the conclusions of archeologists.” Although never directly discussed, presumably the author would dismiss the examples in the Hebrew book.[11]

* I would like to thank the bibliophile par excellence, Marvin Heller, for his assistance and close read of the article, and William Gross, whose library of objects and books is among the richest private collections, and provided most of the images, with credit to the Gross Family Collection. Many are available at the Center for Jewish Art website (https://cja.huji.ac.il/browser.php).

[1] See for example, Rachel Hachlili, The Menorah, The Seven-Armed Candelabrum (Leiden: Brill, 2001) who exhaustively catalogs the examples of menorah depictions but does not discuss the Hebrew book.

[2] For the history of the menorah, see Steven Fine’s comprehensive study, The Menorah, From the Bible to Modern Israel (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016). Also see L. Yarden, The Tree of Light, A Study of the Menorah (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1971.

[3] Avraham Yaari, Degali Madfisim ha-Ivriyim (Jerusalem: Hebrew University Press, 1944), see index s.v. magen David and menorah; Yitzhak Yudlov, Degali Madfisim (Jerusalem: Old City Press, 2002); For examples of lions, eagles, and fish, see Marvin Heller, Essays on the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Leiden: Brill, 2021), 5-84

[4] See Steinschnider, Catalogus Libr Hebr., col. 2984, no. 8761 (discussing his surname); Yaari, Degali, 128-29; Encyclopeadia Judaica, vol. 13 col. 101-02 (1996); David Amram, The Makers of Hebrew Books in Italy (London: Holland Press, 1963), 367-71.

Parenzo may have a second printers mark that only appears once, in the 1574 Bragadini edition of the Rambam. On the verso of the title page is, according to EJ, “a rather daring design” illustrating Venus hurling arrows at a seven-headed dragon. Unmentioned is Venus’ clothes, or lack thereof.

This mark is similar to the Cremona-Sabbioneta, printer, Vincenzo Conti’s mark, with the seven-headed hydra. His, however, has Hercules rather than Venus.

A nude Venus was also used by Allesandro Gardano for his printers mark. He only published one book, a pocket edition of the Shulhan Orakh in 1578. A naked Venus rising appears at the bottom.

Hans Jacob, who published in Hanau in the 1620s, also has a naked Venus rising from a seashell at the bottom of at least four works, R. Moshe Isserless, Torat Hatas, Sefer Mahril, and a Siddur.

For a detailed discussion of Parenzo’s printing activities, see A.M. Haberman, “Ha-madfeshim beni R’ Yaakov Parenzoni be-Veniztia,” in Areshet 1 (1959), 61-88.

[5] See Yudolov, Degali Madfisim (Jerusalem: Old City Press, 2002), 23-24.

[6] See Marvin Heller, “Jacob ben Samuel Bunim Koppelman: A Sixteenth Century Multi-Faceted Jewish Scholar,” Gutenberg-Jahrbuch (Mainz, 2018), pp. 195-207.

[7] Introduction Imrei Sefer, Lublin 1697 (on differences in the printings of the Imrei Shefer see Yudolov, Areshet, 6 (1981) 102 no. 7); Biurim, Venice 1693; R. E. Katzman, “Rabbi Nathan Nata Shapiro – Ha-Megaleh Amukot” in Yeshurun 13 (Elul 2002) 677-700; Introduction [R. E. Katzman], Seder Birkat HaMazon im Pirush shel R. Noson Shapiro, 2000 Renaissance Hebraica, 1-10.

[8] His original surname may have been Strimers. See Shimeon Brisman, A History and Guide to Judaic Bibliography (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1977), 267n.33. For additional biographical information see id. collecting sources.

[9] Dan Rabinowitz, “Yarlmuke: A Historic Cover-up?,” (here) Hakirah (4).

[10] Regarding the map, see Harold Brodsky, “The Seventeenth-Century Haggadah Map of Avraham Bar Yaacov,” in Jewish Art 19-20 (1993-1994): 149-157; David Stern, “Mapping the Redemption: Messianic Cartography in the 1695 Amsterdam Haggadah,” in Studia Rosenthaliana 42/43 (2010-2011), 43-63; Amir Cahanovitc, “Mappot be-haggadot pesah” (Masters thesis, Achva Academic College, 2015), 34-85. For a discussion of this edition and reproductions of some of its images and a comparison with Mathew Merian’s illustrations see Cecil Roth, “Ha-Haggadah ha-Metsuyyeret she-bi-Defus,” Areshet 3 (1961), 22-25; Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Haggadah and History (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 2005), plates 59-62, 67, 69.

[11] See R. Yisrael Yehuda Yakob, “Tzurot Kani Menorah,” in Or Yisrael 18 () 131-139; R. Nahum Greenwald, “Kani Menorah Ketzad Havei,” in Or Yisrael 18 () 140-154.