Armin Wilkowitch about Shabbes Shekolim in his youth in Russia

Armin Wilkowitch about Shabbes Shekolim in his youth in Russia

by Gabriel Wasserman and Phillip Minden

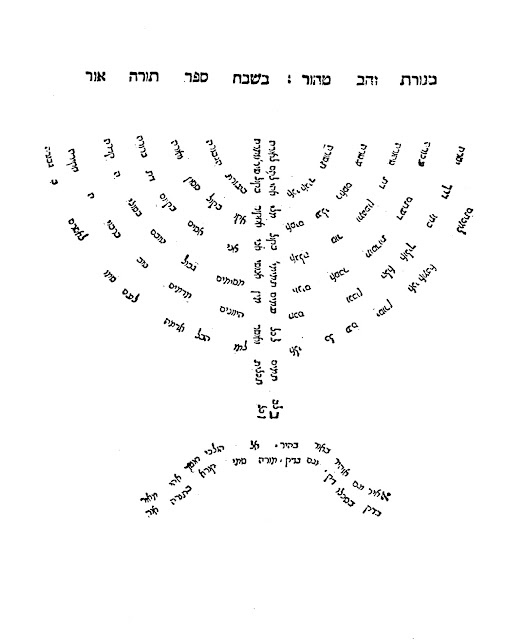

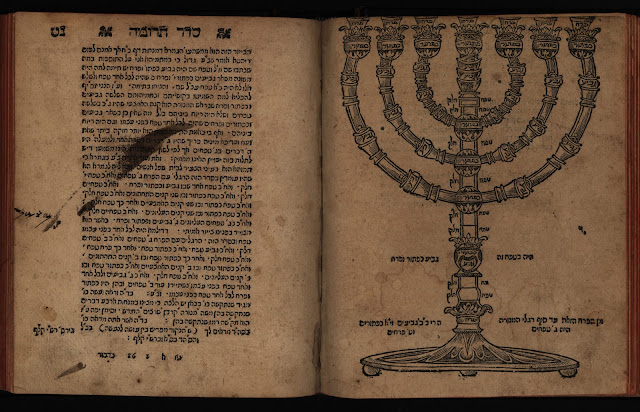

Shabbes Shekolim (Shabbat Sheqalim) is the first of the four special Sabbaths in or near the month of Adar, when special passages are read from the Torah. In addition to the special readings from the Torah, Ashkenazic Jewry has distinguished these four Sabbaths with the inclusion of special piyyutim in the Sabbath service; these piyyutim – most, and perhaps all – are by Eleazar b. Qallir (or Qillir) of sixth- to seventh-century Eretz Yisrael, and they have been part of the liturgy of Ashkenazic Jewry ever since there has been such a thing as Ashkenazic Jewry, since before the year 1000 CE. Although many Ashkenazic communities today omit the piyyutim for Shekolim, happily there are still many Ashkenazic communities that maintain them through today, unlike many piyyutim for other occasions in the year, which have suffered almost complete extinction in living usage.

(As an aside: In the middle ages, many non-Ashkenazic communities, as well, recited piyyutim, different from the Ashkenazic ones, on the four special Sabbaths of Adar. These have fallen into complete disuse today, other than the piyyut “Mi Khamokha” by R. Judah Hallevi for Shabbat Zakhor. These piyyutim will not be the subject of this post.)

In the past, Shabbes Shekolim and the recitation, or singing, of these piyyutim had an aura of great emotional significance for many Ashkenazic communities. As an example of this, the Seforim Blog will present here a piece by Cantor Armin Wilkowitsch, originally published in the Österreichisch-Ungarische Cantoren-Zeitung (supplement to Die Wahrheit), vol. 24 no. 10 (4 March 1904), p. 10. Wilkowitsch writes here about the composition of a setting for the piyyut “Eshkol Ivvuy” (אשכל אווי), the opening of the piyyutim for Musaf of this Sabbath. Wasserman’s research, in a project to collect musical settings for all Ashkenazic piyyutim for special Sabbaths, has uncovered thirty different musical settings for “Eshkol Ivvuy,” and further research may discover far more; this piyyut was clearly very important to cantors, and communities, in generations preceding ours.

According to the biography on Geni.com, Cantor Wilkowitsch, was born in Kalvarija, in the Russian Empire (see map here), today in Lithuania. He lived most of his adult life in the Austro-Hungarian empire, and served as chief cantor of a community in Eger (Erlau, Cheb), in Hungary, for 32 years. In 1939, under Nazi occupation, Wilkowitsch got a visa to escape to America, to join his wife and children who were already there. He boarded the ship, but, in light of the terrible events going on in Europe at the time, he lost the will to live and committed suicide by jumping off the ship. Very sad, and creepy.

In his youth, Wilkowitsch was a meshorer in his native Russia. Meshorerim were a standard phenomenon in pre-modern Ashkenazic synagogues: a group of men and small boys who would accompany the cantor as a kind of choir, though without the Western rules of four-part counterpoint that define modern choirs.

Perhaps the most picturesque line in the story is: “the Special Sabbaths are coming, which are soon bound to chase the polar bear out of the land” (es kommen die ausgezechneten Sabbathe, die den Eisbären bald aus dem Land verjagen).

Wilkowitsch refers to a species of fish, eaten at shalleshuddes, by the Yiddish word shtinkes. This word may be familiar to some readers of this blog from halakhic literature (see, e.g., the commentary of Rashash on Sukka 18a, and here).

The text of Wilkowitch’s piece will be presented here, first in the original German (the educated language throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire) and then in English translation. Hopefully it will give the readers a sense of what Shabbes Shekolim was like in those bygone days – as Wilkowitsch writes, in the Italian expression that concludes his story, tempi passati.

Jugenderinnerungen.

Von Kantor Armin Wilkowitsch.

Jüngst suchte ich unter meinen alten, längst ad acta gelegten Notenblättern herum. Wie pochte da plötzlich mein Herz, und als begegnete ich meinen besten Jugendfreunden, die mir Grüße von meiner Heimat brachte und längst vergangene und verschollene Geschichtchen auffrischten, so sprachen mich diese vergilbten, nach Moder riechenden Notenblätter an. Es waren hunderte von ein- und mehrstimmigen Kompositionen, die ich mir von verschiedenen Chasanim auf meinen Meschorer-Wanderungen mit vieler Mühe erworben hatte. Darunter auch russische und jüdisch-deutsche Liedlein, selbst Sabbathsemiroth, wie Zur mischelo ochalnu, oder Joh, ribbon olam, die ich in meinem Elternhause, im Vereine mit meinen Geschwistern, allsabbathlich sang. Später, als ich Einblick in die Harmonielehre gewann, gab ich den Semiroth regelrechte Rhythmen und bearbeitete sie für zwei Soprane und Klavierbegleitung.

Unter diesen losen Blättern fand ich u. a. für Sabbath-Schekolim einen Eschkol, welcher als Introduktion eine längere, polonaiseartige Melodie vorgespannt hatte und in einer „phrygischen“* Tonart sich bewegte. Herr Oberkantor Singer-Wien nennt, wenn ich nicht irre, diese Skala „jüdische Tonleiter.“ Den russischen Chasanim ist aber meines Wissens keine jüdische Tonleiter bekannt und, wie gerne ich auch uns Juden eine Eigenart in der Musik einräumen möchte, muß ich trotzdem gestehen, daß ich dieser Skala schon bei mehreren kleinrussischen Volksliedern begegnete; auch das rumänische Volkslied dürfte wohl diese Tonart sich zu eigen gemacht haben.** Daß Anton Rubinstein die Melodie für die Worte: „und der Sklave sprach“, in seinem „Asra“ einem jüdischen Chasan abgelauscht hat, möchte ich stark bezweifeln. Das eine ist jedoch gewiß, daß den Deutschen diese Intervalle fremd sind, aber deswegen sind sie noch nicht speziell „jüdisch“.

Bei diesem Eschkol verweilte ich lange, lange…. Habe ich doch denselben „mitkomponieren“ geholfen.

Der Kantor in Rußland betet nicht jeden Sabbath vor, höchstens, daß er am Sabbath-meworachim Jehi rozôn und Jechadschehu absingt, das weitere betet ein Balbos oder der Schammes, und hat der Chasan Chanukalichtlein mit den Meschorerim und Klesmorim entzündet, dann hält er seinen Winterschlaf, bis Sabbath-Schekolim, der erste von den ausgezeichneten Sabbathen, ins Land zieht.

Hui, wie tobt draußen der Sturm! Neue Schneeflocken häufen sich auf die längst zu Eis erstarrten und der grausame Winter herrscht noch mit unbeschränkter Macht. Was gilt ihm die Armut? Was die Not? Despot ist Despot! — Aber im Herzen regt sich die Hoffnung: es kommen die ausgezeichneten Sabbathe, die den Eisbären bald aus dem Lande verjagen, und ein Frühlingsahnen überkommt die geplagte Menschheit.

Es war Sabbath vor Schekolim. Wir, Meschorerim, saßen beim Chasan und halfen ihm zum Scholasch-sudos die länglichen, schmalen Stinkes (Fischlein) vertilgen. Da sprach Schimschon, der Tenor: „Nu, Chasanleben, was wird sein mit eppes a neuen Eschkol? Wieder und aber die alten Trallalaikes?!“ Der Chasan ließ sich Majim-acharonim zum „Benschen“ geben und machte dann eine Handbewegung, die soviel heißen sollte, wie: „Bleibt alle hier!” Nach dem Tischgebet sprach er: „Paßt auf!“ und fing leise eine Melodie zu singen an. Diese Melodie sangen wir, Soprane, einigemal nach, der Chasan sang indessen mit den Altisten die zweite Stimme, während die Tenöre und Bassisten sich nach eigenem Gutdünken ihre Stimmen bildeten. Und so entstand in zirka einer Stunde ein Eschkol fix und fertig, mit dem wir dann „die Welt eingenommen haben.“ Tempi passati!

Childhood memories

By Cantor Armin Wilkowitsch

Recently, I leafed through my old sheet music I had long filed away. How did my heart suddenly pound, and these yellowed sheets with their fusty odour talked to me as if I were meeting my dearest boyhood friends, who brought greetings from my homeland and revived stories long past and lost. There were hundreds of compositions for one and for several voices, which I had acquired with great effort from several chazzanim during my meshorer wanderings. Among them also Russian and Jewish-German songs, even Sabbath zemiroth such as Tzur mishelo ochalnu or Yoh, ribbon olam, which I used to sing every Sabbath in my parental home together with my siblings. Later, having gained some insight into harmonics, I gave regular rhythms to the zemiroth and arranged them for two sopranos with piano accompaniment.

Among other things, I found an “Eshkol” for Sabbath Shekolim in these unbound leaves, which was preceded by a longer polonaise-like tune as an introduction and moved in a “Phrygian”* mode. If I am not mistaken, Chief Cantor Singer of Vienna calls this scale “Jewish mode”. As far as I know, though, the Russian chazzanim are not aware of any Jewish modes or keys, and much as I should like to grant an original feature in music to us Jews, I have to concede that I’ve met this scale in several Little Russian [=Ukrainian] folk songs already, and it can be stated that the Roumanian folk song has embraced this mode as well.** I strongly venture to doubt that Anton Rubinstein overheard a Jewish chazzan and copied the tune for the words “und der Sklave sprach” [“and the slave said”] in his “Der Asra”. These intervals are certainly alien to Germans, but that does not make them specifically “Jewish”.

I dwelled long on this “Eshkol”… After all, I helped compose it.

A cantor in Russia doesn’t lead the prayers every Sabbath; at most he will sing “Yehi rotzon” and “Yechadshehu” on Sabbath Mevorachim, and a balbos or the shammes will lead the other prayers. As soon as the chazzan has kindled the Chanukkah lights with the meshorerim and the klezmorim, he goes into hibernation until Sabbath Shekolim, the first of the Special Sabbaths, comes round.

Oh, how does the storm rage out there! Fresh snowflakes pile onto those long frozen to ice, and grim winter still rules with unlimited power. What does it care about hardship? About affliction? A despot is a despot! But hope is rising in the hearts: the Special Sabbaths are coming, which are soon bound to chase the polar bear out of the land, and a hunch of spring spreads in plagued humankind.

It was the Sabbath before Shekolim. We meshorerim were sitting with the chazzan, helping him to devour the oblong, narrow shtinkes (little fish) during sholash-sudos. Shimshon, the tenor, then said: “So, my dear chazzan, is there maybe going to be a new ‘Eshkol’? Again and again the old trallalaikes?” The chazzan had mayim acharonim given to him for “benshen” and then waved his hand in a sense of “Everybody stay here!” When Grace After Meals was finished, he said “Listen!” and started to sing a tune in a low voice. We, the sopranos, repeated this melody a few times, the chazzan added the second voice with the altos, while the tenors and basses formed their voices as they seemed fit. And so, an “Eshkol” came into being, all done and ready in the course of approximately one hour, with which we then “conquered the world”. Tempi passati!

[1] d, es, fis, g, a, b, cis, d. Warum die Chasanim diese Skala „phrygisch“ nennen, weiß ich freilich nicht, vielleicht aber findet sich ein Kollege, der uns Aufschluß zu geben vermag.

[2] Ich hatte einst Gelegenheit, in Wien eine Familie kennen zu lernen, die mehrere Jahre in Bukarest gelebt hatte. Eine Tochter des Hauses, die sich dem Gesangsstudium widmen wollte, trug mir ein rumänisches Lied mit Klavierbegleitung vor, in welchem ich wieder derselben Tonleiter begegnete.

[3] D, E flat, F sharp, G, A, B flat, C sharp, D. Why the chazzanim call this mode “Phrygian”, I cannot tell, however. But maybe a fellow cantor will be found who can enlighten us there.

[4] Once I had the opportunity to make the acquaintance of a family in Vienna who had lived in Bucharest for several years. The daughter of the house, who intended to dedicate herself to voice studies, performed a Roumanian song with piano accompaniment for me, in which I again encountered the same mode.