Marc B. Shapiro

1. Numbers 34:15 states: “Two and a half tribes have taken their inheritance on the side of the Jordan by Jericho, to the front, eastward.”

Rashi comments:

קדמה מזרחה: אל פני העולם שהם במזרח, שרוח מזרחית קרויה פנים ומערביות קרויה אחור לפיכך דרום לימין וצפון לשמאל

This passage is translated as follows in ArtScroll’s Sapirstein edition:

To the Front, Eastward: This means to the front of the world, which is in the east, for the eastern direction is called “face” and the western direction is called “back.” This is why the south is to the right and the north is to the left.

What does the “front of the world” mean? Furthermore, how could Rashi say that south is to the right? Anyone who looks at a map can see that south is not to the right and north is not to the left. Rather east is to the right and west is to the left.

ArtScroll begins its explanation by referring to Psalms 89:13: צָפוֹן וְיָמִין אַתָּה בְרָאתָם

“The north and the south [right], Thou hast created them.” What we see from this verse is that “right” is used synonymously with “south”, which means that “north” also signifies “left”. But what does this mean, that “south” is “right” and “north” is “left”?

See also Genesis 13:9: אִם–הַשְּׂמֹאל וְאֵימִנָה וְאִם–הַיָּמִין וְאַשְׂמְאִילָה

Onkelos and Ps.-Jonathan translate: אם את לצפונא אנא לדרומא ואם את לדרומא אנא לצפונה

As you can see, the Targumim also understand “right” to mean south and “left” to mean north.

Genesis 14:15 states: וַיִּרְדְּפֵם עַד–חוֹבָה אֲשֶׁר מִשְּׂמֹאל לְדַמָּשֶׂק

Old JPS translates: “[He] pursued them unto Hobah, which is on the left hand of Damascus.” But this is incorrect. The word משמאל here means “to the north”, and this is how it appears in the new JPS (and also in ArtScroll). See also Ezekiel 16:46 where again the words “right” and “left” refer to south and north.[1]

In its commentary to Rashi, Numbers 34:15, ArtScroll provides examples of other places where Rashi explains “south” to mean “right”. For example, Ezekiel 10:3 states: וְהַכְּרֻבִים עֹמְדִים מִימִין לַבַּיִת בְּבֹאוֹ הָאִישׁ. “Now the cherubim stood on the right side of the house, when the man went in.” Rashi comments:

מימין לבית: בדרום

“On the right side of the house: In the south [of the Temple].”

ArtScroll does not mention Rashi, Genesis 35:18, where he explains the name בנימין as meaning “of the south”, that is, the only son who was born in the south.

Returning to Rashi’s comment in Numbers 34:15, where he says that south is to the right and north is to the left, ArtScroll explains as follows: “When one faces east, his right is to the south, his left is to the north, and his back is to the west.” This explanation is earlier found in the Silbermann translation of Rashi, Exodus, p. 261: “In reality these terms describe the points of the compass relative to one who is facing the place of sun-rise (מזרח) so that ימין, the right, is the South and שמאל, the left, is the North.” Neither ArtScroll nor Silbermann mention that this explanation is already found in Nahmanides, Exodus 26:18.

Now let us look at two passages in Maimonides. In Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Terumot 1:9, Maimonides states:

איזו היא סוריה? מארץ ישראל ולמטה כנגד ארם נהריים וארם צובה כל יד פרת עד בבל כגון דמשק ואחלב וחרן ומגבת וכיוצא בהן עד שנער וצהר הרי היא כסוריה

What constitutes Syria? From Eretz Yisrael and below parallel to Aram Naharaim and Aram Tzovah, the entire region of the Euphrates until Babylonia, e.g., Damascus, Achalev, Charan, Minbag, and the like until Shinar and Tzahar. These are considered like Syria.

I have underlined the problematic word. How can Maimonides say that Aram Naharaim etc. are below the Land of Israel? As R. Mordechai Emanuel notes, the Rambam is placing Damascus south of the Land of Israel which is clearly mistaken.[2] Here is the map, and if we inserted all the places places Maimonides mentions we would find them north of Israel.

R. Isaac Klein writes as follows in his translation in the Yale Judaica Series (p. 436):

“Outward” – literally “below.” The term is due to the belief that the Land of Israel was situated higher than all other lands, hence all other countries were considered below it. In modern Hebrew he who immigrates into Israel is termed oleh, “he who has ascended,” while he who leaves Israel is called yored, “he who has descended.”

The Touger edition of the Mishneh Torah comments:

The term “below” in this context is problematic. It does not mean “south,” because significant portions of Syria are more northerly than Eretz Yisrael. Some commentaries understand it as meaning in height, because as Kiddushin 69b states, Eretz Yisrael is higher than other lands.

Rambam le-Am states that the word “below” should be understood as meaning “outside of”, which is how Klein also translated the passage:

כלומר, מחוצה לה, וכתב “למטה” לפי שארץ ישראל גבוהה מכל הארצות – קידושין סט:

Yet this doesn’t make much sense. Maimonides is giving the borders of Syria so saying מארץ ישראל ולמטה cannot possibly mean “outside Eretz Yisrael”. The fact that Eretz Yisrael is higher than the surrounding lands is also not relevant. In other words, the three editions of the Mishneh Torah we have just mentioned don’t have a clue as to why Maimonides writes למטה, when anyone looking at a map would conclude that he should have written למעלה.

The same problem can be seen in Hilkhot Kiddush ha-Hodesh 11:17 where Maimonides states that Jerusalem is found below the equator.

מתחת הקו השוה המסבב באמצע העולם

Both Solomon Gandz in the Yale Judaica Series and the Touger edition translate this as “north of the equator” without explaining how מתחת can mean north. Again, anyone can look at a map and see that Jerusalem is above the equator, so what is going on here?

The answer to the questions I have asked is that maps in the Islamic world were generally oriented with south at the top. I can do no better than cite Jerry Brotton’s wonderful bookת A History of the World in Twelve Maps (London, 2012), pp. 58-59:

Most of the communities who converted to Islam in its early phase of rapid international expansion in the seventh and eighth centuries lived directly north of Mecca, leading them to regard the qibla as due south. As a result, most Muslim world maps, including al-Idrisi’s, were oriented with south at the top. This also neatly established continuity with the tradition of the recently conquered Zoroastrian communities in Persia, which regarded south as sacred.

This orientation would have appeared on the maps that Maimonides was familiar with, and thus it makes sense for him to describe Aram Naharaim, etc. as below Israel, or Jerusalem as below the equator, as that is what he saw when he looked at a map.[3] Here is an example of such a map by the famed twelfth-century cartographer Muhammad al-Idrisi. This map is known as Tabula Rogeriana as it was made for King Roger II of Sicily.[4]

As you can see, Saudi Arabia is on top. Here is a twentieth-century map which also puts south on the top.[5]

We have other examples of maps in Jewish sources that show the directions differently than what we are used to. For example, here is Gittin 7b and the maps in Rashi show west on top.

We also have maps in medieval manuscripts of Rashi’s commentaries that show east on top, as well as north on top.[6]

Here is Maharsha, Gittin 7b, which shows west on top. Below this you can see the map in R. Meir of Lublin’s commentary that has east on top.

Here is Maharsha, Berakhot 61b, and east is on top.

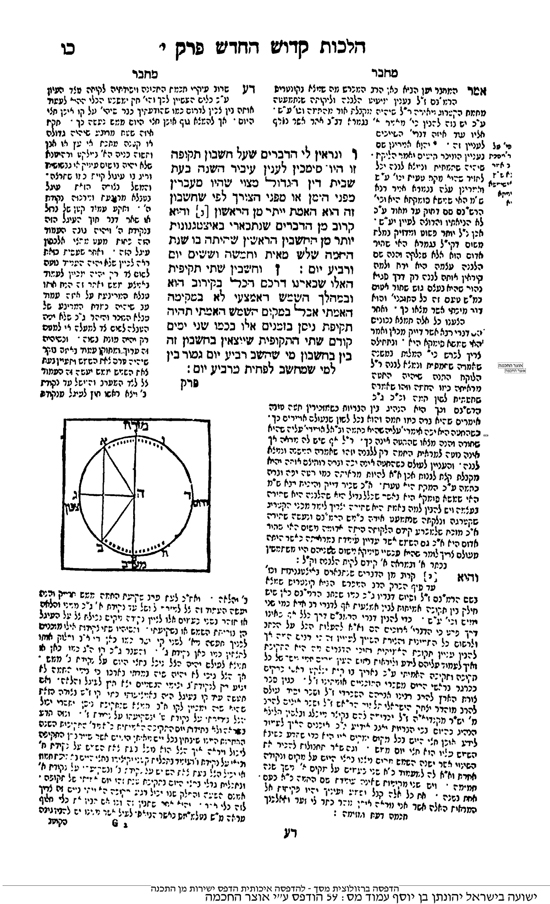

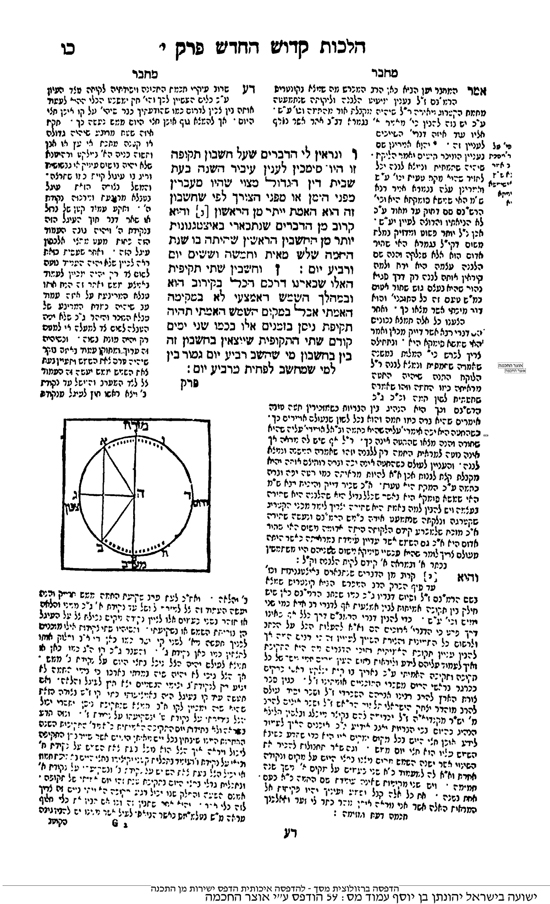

Here is a page from R. Jonathan ben Joseph’s Yeshuah be-Yisrael, a 1720 commentary on Maimonides’ Hilkhot Kiddush ha-Hodesh (ch. 10), and you can see again that east is on top.

Many people probably assume that what we have seen are printers’ mistakes, but that is not the case. European cartographers regularly put east on top, as Jerusalem was in the east relative to Europe, and the top was often regarded as the most important place on a map.[7] We also have examples from Europe with the west on top, although this is much rarer.[8] The important point is that our current maps that have north on top are not any more correct than these other maps. It is simply a matter of convention which direction should be on top, and interested readers are referred to Brotton’s book mentioned already.

As we have been discussing maps, here are some examples of what appear to be geographical mistakes in rabbinic literature, in no particular order. (In a future post I will deal with rabbinic views about whether the earth is round or flat, and why they thought there was no human habitation in the southern hemisphere.)

Rashi, Shabbat 65b, s.v סהדא, and Kiddushin 71b s.v. עד נהר, states that the Euphrates flows from the Land of Israel to Babylonia.[9] The Talmud, Shabbat 65b, quotes Rav that when the water rises in the Euphrates this is a sign that there has been rain in the Holy Land.[10] I believe the simple explanation of this passage, contrary to Rashi, is that there was an assumption that if there was significant rain in Babylonia then there was also rain in Eretz Yisrael. Presumably, this is also the meaning of pseudo-Rashi to Nedarim 40a s.v. סהדא (this commentary is not by Rashi):

כשנהר פרת גדול הוי עדות לגשמים שיורדין לא“י דא“י גבוה מכל הארצות ובאין גשמים ונופלין בפרת ומתגדל מהן

Rashi, however, had a different approach, and believed that the Euphrates flows all the way from the Land of Israel to Babylonia, so when the level of the Euphrates is raised this is proof that in the Land Israel it rained. Yet this is incorrect as the Euphrates does not flow from the Land of Israel to Babylonia. See also Tosafot, Shabbat 65b s.v. סהדא, who also think that the Euphrates is found in the Land of Israel, but reject Rashi’s understanding since Tosafot claims that rivers only flow from east to west (so the Euphrates must flow from Babylonia to the Land of Israel).[11]

However, R. Samuel Strashun, note to Shabbat 65b, tells us that he looked at a map and saw that the Euphrates indeed flows from west to east. He further notes that the Danube River also flows from west to east, meaning that Tosafot’s reason for rejecting Rashi is incorrect. We know that the Tosafot on different tractates do not necessarily come from the same school, and Tosafot, Bekhorot 44a, s. v. לא, and 55b, s.v. מיטרא, mention Rashi’s idea that the Euphrates flows from the Land of Israel to Babylonia.

Returning to Rashi, many have wondered how Rashi could describe the Euphrates as flowing from the Land of Israel, although I don’t see what is so difficult, since without accurate maps how could one expect Rashi to have perfect knowledge of the geography of the Middle East?[12] Nahmanides famously records in his commentary to Genesis 35:16 that only when he came to the Land of Israel and could see the geography did he realize that an explanation he had offered was incorrect. Interestingly, Nahmanides never updated his commentary to Genesis 35:18 where he criticizes Rashi for his supposed geographic error regarding Aram Naharaim. Yet most would say that it is Ramban who is mistaken when he writes that “Aram is southeast of the Land of Israel, and the Land of Israel is to its north.”[13]

R. Strashun calls attention to what he thinks is another geographical mistake in Rashi. In his note to Sukkah 36a he mentions that Rashi is mistaken (היפך המציאות) about where Kush is located, as R. Strashun tells us that Kush is Ethiopia. However, as R. Yaakov Hayyim Sofer has noted, Rashi routinely explains Kush as being identical with הינדואה, not Ethiopia. Presumably, Rashi understands הינדואה as India, which means that Hodu, mentioned in Esther 1:1, is a different place. While most people have understood Esther 1:1 to mean “from India[14] unto Ethiopia,” Rashi on Esther 1:1 tells us that Kush and Hodu are next to each other (which is one talmudic opinion in Megillah 11a).

Leaving aside Rashi’s identification of Kush as הינדואה, the real problem is Rashi’s understanding of הינדואה as a different place than Hodu. Interested readers can examine my earlier post here where I discuss this issue and explain why הדו has a dagesh in the dalet.[15] As for Kush, there is no uniformity of opinion as to what it refers to, and it is possible that the different biblical references do not all refer to the same place.[16] In agreement with Rashi, Tosafot, Bava Batra 84a s.v. בצפרא, mention that the Midrash places Kush in the east. R. Jacob Emden, who knew his geography, states that in addition to Ethiopia there was another land near India that was called Kush.[17] No less a figure than R. Abraham Maimonides confesses that he does not know where the Kush mentioned in Genesis 2:13 is to be found.[18]

There is actually a long mountain range called Hindu Kush that passes through Pakistan, which until the second half of the twentieth century was included in the territory called India.[19] Since the term “Hindu Kush” has been in existence for over a thousand years, it was obviously not incorrect for medieval writers to speak of a Kush near India. In my earlier post I also cited P. S. Alexander who writes: “It was a common view in ancient geography, shared by Ptolemy and probably also the author of the book of Jubilees . . . that Ethiopia was joined to India in the east. It is this idea that lies behind the [talmudic] statement that Cush and Hodu are adjacent.”[20] He also notes that the Indians’ dark skin was a reason for the identification. Furthermore, Alexander tell us, there was an ancient belief that there was a land connection between Ethiopia and India south of the Indian Ocean.

Speaking of geographical inaccuracies, Rabbi Natan Slifkin writes as follows in his new book Rationalism vs. Mysticism, p. 517:

The Zohar makes many statements about places in the Land of Israel which are incorrect, but which would be perfectly understandable if they were authored by someone living in Spain. For example, in multiple places the Kinneret is described as being in the territory of Zevulun, and as being the source of the chilazon that produces techelet, even though it was actually derived from the Mediterranean. Lod is described as being situated in the Galilee, and Cappadocia is described as a village near Sepphoris rather than as a province in Asia Minor.[21]

Avraham Korman called attention to a passage in Yalkut Shimoni, Joshua, remez 15.[22] The Midrash is commenting on the verse in Joshua 3:16:

וַיַּעַמְדוּ הַמַּיִם הַיֹּרְדִים מִלְמַעְלָה קָמוּ נֵד–אֶחָד, הַרְחֵק מְאֹד באדם (מֵאָדָם) הָעִיר אֲשֶׁר מִצַּד צָרְתָן

The waters which came down from above stood, and rose up in one heap, a great way off from Adam, the city that is beside Zarethan

The Midrash states:

שמעת מימיך עיר נקראת אדם? אלא על אברהם נאמר “והאדם הגדול בעקים” (יהושע יד, טו)

Korman believes this Midrash was authored by someone who did not know the Land of Israel, and thus could not believe that there was actually a city named Adam. Therefore, the sage offered a midrashic understanding of “Adam”. Yet there was indeed such a city, and it is mentioned in Yerushalmi, Sotah 7:5. It was later called Damiyeh by the Arabs.[23] However, Korman’s notion that the author of the Midrash did not know any of this, and the passage should be read as a denial of the literal existence of the city of Adam, strikes me as complete nonsense.

R. Ovadiah Bartenura in his commentary to Genesis 12:6 strangely does not realize that Hebron is in the south of biblical Eretz Yisrael.[24] R. Ovadiah would eventually journey to the Land of Israel, so this comment must have been made before his arrival there.

R. Moses Sofer, She’elot u-Teshuvot Hatam Sofer, Even ha-Ezer II no. 49, cites Deuteronomy 11:24, which refers to the boundaries of “Greater Israel.”

כָּל–הַמָּקוֹם אֲשֶׁר תִּדְרֹךְ כַּף–רַגְלְכֶם בּוֹ לָכֶם יִהְיֶה מִן–הַמִּדְבָּר וְהַלְּבָנוֹן מִן–הַנָּהָר נְהַר–פְּרָת, וְעַד הַיָּם הָאַחֲרוֹן יִהְיֶה, גְּבֻלְכֶם

“Every place whereon the sole of your foot shall tread shall be yours: from the wilderness, and Lebanon, from the river, the river Euphrates, even unto the Western Sea shall be your border.”

R. Sofer wonders about the words מן המדבר והלבנון, as these are both in the south, so how could this establish borders when what the verse should have is a site in the north together with a site in the south?

ויש לי מקום עיון בלשון הקרא . . . שלכאורה אין לו שחר כי המדבר והלבנון הוא גבול דרומית לא“י שבין צפון ים סוף לדרום א“י

This passage is surprising, to say the least, as how could R. Sofer say that Lebanon is in the south of Israel? Ever since this passage appeared in print it has mystified readers and many have simply thrown up their hands without any explanation, as it is impossible to imagine that R. Sofer did not know that Lebanon is located to the north of Israel. R. Sofer was attacked on this point by Leopold Loew in his Hungarian periodical Ben Chananja.[25] R. Joseph Natonek in a German booklet offered an explanation of R. Sofer, but I confess to not understanding his point. Here is how R. Natonek’s position is summarized by Shmuel Weingarten.[26]

הרב נטונק מוכיח איפוא שה“אתנחתא” בדברי החת“ס צריכה להיות אחרי המלים “שבין צפון” והוו של והלבנון אינה ו‘ החבור (konjunktiv) אלא ו‘ הפרוד (disjunktiv) . . . דברי החת“ס ברורים איפוא: “כי המדבר והלבנון הוא גבול דרומית לא“י שבין צפון” מן המדבר שבדרום עד הלבנון שבצפון וכו‘

R. Sofer made his comment regarding Deuteronomy 11:24, and he sees the words מן המדבר והלבנון as indicating that the wilderness and Lebanon are in the same place. The same words are found in Joshua 1:4:

מהמדבר והלבנון הזה ועד הנהר הגדול נהר פרת

“From the wilderness, and this Lebanon, even unto the great river, the river Euphrates.”

Here, too, if we didn’t already know where Lebanon is we would assume that the wilderness and Lebanon are together, as that is the simplest way to read the text. It is so obvious, in fact, that Metzudat Tziyon is forced to explain “Lebanon” as referring to the name of a forest. The Vilna Gaon, in his commentary printed in the Mikraot Gedolot, also does not regard this “Lebanon” as referring to the Lebanon we know but a different Lebanon in the southeast of Israel.[27] So we see that R. Sofer was not alone in his understanding.

Avraham Moshe Luntz, who wrote much about the geography of the Land of Israel, also argues that the “Lebanon” referred to here is not the Lebanon we know.[28] He thinks the verse is referring to the borders of a future Greater Israel and the Lebanon mentioned is actually Wadi al-Abyad in the south, in the Land of Edom. (Abyad=white, which is also the root of the word Lebanon.) However, I don’t know which place he is referring to, as while there is a Wadi al-Abyad in Jordan it is not in the south but on the east of Jerusalem.

Here is how Luntz connects what he says with the Vilna Gaon’s comment (p. 83):

והנה כל הדברים האלה אף כי חדשים הם לא שערום הראשונים בכל זאת הרגיש בהם הגר“א ז“ל מטעם סוד ה‘ ליראיו אם כי לא שמע מעולם מן ועד–אל–אביאט ורק מרוח הקודש אשר הופיע בבית מדרשו כתב בבאורו על הגבולין דיהושע והלבנון זה מזרחו של ארץ ישראל הקרוב לצד דרום ולכן אמר “הזה” ששם היו עומדים והרב בעל תבואות הארץ כתב עליו “נפלאים בעיני דבריו“. אמנם, לא נפלאים ולא רחוקים המה, רק נפלאת היא בעניניו רוח קדשו של הגר“א ז“ל אשר מאת ה‘ נתנה לו.

In Mesorat Moshe, vol. 2, pp. 158-159, R. Moshe Feinstein discusses Venice and Shushan Purim.[29] In the note the following appears:

ואחר כך הזכיר רבינו שונציה שנזכר בפיוטים הוא חלק מרוסיה, פעם היה שם רב אליהו פרושנער, אבל אפשר שונציה שמוזכר בשער דף של ספרים, למקום הדפוס, מכוין ל-Venice [ונציה], שמוצאים זה על ספרים עתיקות, בשנים שברוסיה וכו‘ לא היו בתי דפוס, ואפשר שבאיטליה כן היה.

R. Moshe says that the Venice that is mentioned in piyutim is not Venice, Italy, but a place in Russia. He must have had in mind the town of Vinnitsa – וויניצא – which you can read about here. He also says that R. Elijah Feinstein (of Pruzhan) was there, which appears to mean that he served as a rabbi in Vinnitsa (although this appears to be inaccurate). As for the first point about Venice being mentioned in piyutim, I have never heard of this and if it is the case, it could only refer to Venice, Italy. Perhaps R. Moshe was referring to something like this book of Yotzrot which on the title page says it was published in Venice, and refers to Venice, Italy.

The note in Mesorat Moshe continues that R. Moshe was aware of the name Venice on the title page of seforim, and thought it is “possible” that this refers to Venice, Italy. This is all very strange, and despite what the note says I find it impossible to believe that R. Moshe did not know that Venice was a center for Jewish printing, even if he did not know the extent of this printing. (Venice was where the first Mikraot Gedolot[30] Bible, as well as the first complete Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds were printed.) I am inclined to assume that this note does not accurately inform us of what R. Moshe’s point was.

Regarding Venice, Rashi has an interesting passage in his commentary to Isaiah 42:10:

ומלואו: הקבועים בים ולא באיים אלא בתוך המים שופכים עפר כל אחד ואחד כדי בית והולכים מבית לבית בספינה כגון עיר ווניציי“א

[Those who go down to the sea and] those therein: Those whose permanent residence is in the sea and not in the islands, but in the midst of the water they spill earth, each one of them, enough for a house, and go from house to house by boat, like the city of Venice.

Rashi mistakenly thought that the islands of Venice–of which there are 118—were man-made. He also seems to have thought that there was only one house on each island and you travel from house to house by boat. Incidentally, as Yitzhak Baer has noted, other than Venice the only other contemporary (European) city Rashi mentions by name is Rome.[31] For the reference to Rome, Baer refers to Rashi’s commentary to Isaiah 33:23, but he neglects to note that Rashi also mentions Rome in his commentary to Micah 7:8. Furthermore, in Bomberg’s 1525 Venice Mikraot Gedolot, Rashi to Zechariah 13:7 reads: את מלך רומי הרשעה. Yet in the standard Mikraot Gedolot the following appears: את מלך בבל.

Manfred Lehmann[32] thought that there was something else related to Venice in Rashi’s commentary to Nehemiah 7:3 where in manuscripts, but not in the Mikraot Gedolot printed version, Rashi explains the word משמרות (watches) as: גיט“א בלעז. Lehmann states that this is the first time the word “Ghetto” appears in Jewish literature, and that the word originates in Venice. Lehmann then states that he doubts that there was already a ghetto in Venice in the days of Rashi. I don’t understand this at all, because if Lehmann (correctly) doubts that there was a ghetto in medieval Venice, then how could he not realize that the word גיט“א cannot refer to “ghetto”. (The Venice ghetto was established in 1516.) This is quite apart from the fact that the word “ghetto” would not make sense in the verse. If you want to know what גיט“א means, the place to look is Moshe Katan, Otzar Loazei Rashi (Jerusalem, 1990), p. 88, where he provides the Hebrew translation of the old French word: תצפיות, מארבים. I must also note that the commentary to Nehemiah attributed to Rashi was not actually written by him.[33]

In the first draft of this post I wrote that I didn’t understand how R. Hayyim Joseph David Azulai, Shem ha-Gedolim, ma’arekhet gedolim, s.v. ע no. 2, could write that R. Ovadiah of Bertinoro came from a town in “Romania.” R. Azulai refers to Romania in Shem ha-Gedolim, ma’arekhet gedolim, s.v. א no. 169, and ma’arekhet seforim, s.v. ח no. 15, and it means Byzantium. I didn’t think it was possible that R. Azulai was unaware that Bertinoro is a town in Italy, some 200 miles from his home in Livorno. Furthermore, I have no doubt that every Torah scholar who lived in Italy in R. Azulai’s day would have known and been proud of the fact that R. Ovadiah came from Italy. So I didn’t know what to make of R. Azulai’s comment. Shimon Steinmetz enlightened me that when R. Azulai refers to Bertinoro as being in Romania, he actually has in mind the Italian historical region called Romagna. In an era before there was a country named Italy, it makes sense that R. Azulai would refer to the region that R. Ovadiah of Bertinoro came from.

Let me offer one final example where the mistake is not made by the medieval authority, in this case Maimonides, but by his critic, R. Jacob Emden. In the Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Tzitzit 2:2, Maimonides writes about how tekhelet is produced: “A chilazon is a fish whose color is like the color of the sea and whose blood is black like ink. It is found in the ים המלח.” We all know that ים המלח means the Dead Sea, and the Dead Sea is referred to as such numerous times in the Bible. R. Jacob Emden is shocked that Maimonides makes the error of thinking that fish could live in the Dead Sea.[3] He ends his comment with the strong words: לכן שיבוש גמור הוא זה לר“מ ז“ל. A number of later commentators also call attention to Maimonides’ “problematic” words, and some refer to R. Emden’s comment.

Yet the mistake here is not by Maimonides but by R. Emden, who didn’t realize that when Maimonides referred to the “salt sea” he meant the Mediterranean.[35] Maimonides was just translating into Hebrew the Arabic term used to designate the Mediterranean[36]: אלבחר אלמאלח. At the end of his Commentary on the Mishnah, Maimonides mentions that he wrote this work while on אלבחר אלמאלח, and in his commentary to Kelim 15:1 he speaks of ships that that go from the Land of Israel to Alexandria by way of אלבחר אלמאלח. In the Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Arakhim ve-Haramim 8:8, the best texts have: ישליכן לים הגדול ים המלח כדי לאבדן, thus explicitly identifying what he means by “salt sea”. When Maimonides refers to the Dead Sea in Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Shabbat 21:29, he calls it ים סדום [37]. This is not his own term as Bava Batra 74b refers to ימה של סדום. Yerushalmi, Shabbat 14:3 refers to the Dead Sea as מי סדום. Interestingly, Yerushalmi, Kil’ayim 9:3 refers to it as ימא דמילחא [38].

2. In a number of posts I have documented how material from an archive at Bar-Ilan University ended up in various auctions. I was quite surprised that no one in any position of authority at Bar-Ilan seemed to care at all about what I had discovered. R. Elli Fischer recently discovered something similar, but with a much more expensive manuscript from the Jewish Theological Seminary. The story in this case is that the manuscript was sold by JTS. See the report here. Maybe the story with the archive from Bar-Ilan is similar to what happened with JTS, and it was actually Bar-Ilan which sold the archive. This would explain why they expressed no interest in finding out how the archive ended up at auction.

* * * * * * * *

Some years ago Rabbi Jonathan Sacks told me that in addition to writing scholarship I should also write for the larger world. He specifically mentioned that I should write for the Wall Street Journal. I finally took up his suggestion a few months ago and submitted an opinion piece to the Journal. They get hundreds of submissions a day, so I was not very surprised when they turned it down. Maybe the message in this is that I should stick to what I do best instead of involving myself in the culture wars. Rather than having the piece go to waste, I present it to you here.

Is it all Bad News at Our Universities?

For many people, the campus seems like a scary place these days. One can read about social justice warriors running roughshod over anyone who crosses the latest woke standards. Professors have been raked over the coals, and worse, for even mildly crossing the new woke thought police. We have also been treated to the spectacle of professors confessing their sins and promising to do better in the future, in scenes that look like they came out of Chinese Cultural Revolution re-education camps.

While I don’t wish to downplay any of this, and there have indeed been shocking violations of free speech at some of the top universities, I think that many Americans are getting a warped sense of what takes place at the typical university. I am sometimes asked by people if my university is anything like what they have been reading about, to which I can happily reply that no, I have never had the misfortune to experience that. To begin with, the various excesses are almost always centered in a few departments in the humanities. As one who teaches in a Theology/Religious Studies Department at a Catholic university—which, it bears noting, had in-person classes this academic year unlike so many other institutions—it is hard to see how the woke mentality and cancel culture would play out. Are we to remove the Bible, Augustine, and Aquinas because passages in these works are not in line with twenty-first century woke values?

This clearly is a non-starter, but just as important is that there has never been a push for this from students, who often are the ones behind the most damaging of campus controversies. I daresay that my experience is no different than my colleagues at hundreds of other colleges and universities in the country, institutions that are not what is commonly called “elite” institutions of learning, but which do a wonderful job in educating a student body that reflects middle-class America. Yes, we have liberal and even progressive students, but what we don’t have in any numbers—or at least I have not come across them—are students who speak woke and know all the Marxist lingo, who can go on and on about intersectionality, white supremacist capitalism, and America as the center of evil in the world, and who get outraged (or pretend to be outraged) at things that even a couple of years ago no one would have batted an eye at.

It is certainly possible that things will change in the future, and the wokeness and cancel culture currently infecting the “elite” universities, as well as so many other aspects of elite society, will filter down to the rest of the country including my university. If this happens, it might be a good time to think of retirement, as I wonder—to give an example from one of my courses—how I could teach about ethics under a woke regime. Could we actually have a unit on Affirmative Action where together with Ronald Dworkin’s spirited defense of racial preferences we also read those who see any discrimination on the basis of race, even if it is called “equity,” as deeply immoral? Could we do the unit on capital punishment where we examine whether our criminal justice system is “systemically racist,” instead of assuming that as a given? Could we focus on abortion, where we examine if women really do have a “right” to choose to terminate a pregnancy? Then there are the student presentations where all subjects are open for discussion, including such hot-button matters as immigration, war, sexual ethics, and transgender issues. Never once has a student tried to shut down the freewheeling class debate or complained that another’s point of view makes them feel “unsafe.” That is the way it should be, and I am confident that is how matters will remain in the vast majority of our colleges and universities. For those who are worried that higher education is leading us into the abyss, I can only say that from where I am standing, it is actually higher education that is succeeding where the “elite” universities have often failed.

* * * * * * * *

[1] Rashi, quoting Midrash Tanhuma, identifies Hobah with Dan. Yet as R. Meir Mazuz notes, it is hard to know what to make of this, as Hobah is described as north of Damascus which is not where the territory of Dan was. See

Bayit Ne’eman: Bereshit 14:15.

[2] “Gevulot Eretz Yisrael (2),”

Ha-Ma’yan 33 (Tevet 5753), p. 15.

[3] This is noted by R. Yisrael Ariel, Otzar Eretz Yisrael (Jerusalem, 2012), vol. 4, p. 13. I have checked numerous editions of the Mishneh Torah and the only one to explain this point is the Makbili edition, Terumot 1:9. Here is the relevant page which also includes a map found in manuscripts which also has south on top.

[4] See here from where I took the map.

[5] This map is found here.

[6] See Portraying the Land: Hebrew Maps of the Land of Israel from Rashi to the Early 20th Century (Berlin, 2018), ch. 1, available here.

[7] They also placed Jerusalem in the center of the known world. There is a commentary attributed to Maimonides on Tractate Rosh ha-Shanah. According to this commentary, the Land of Israel is to be regarded as on the western part of the world. Where then is Europe to be placed?

Here is “Maimonides” comment, Hiddushei ha-Rambam le-Talmud, ed. Zaks (Jerusalem, 1963), p. 79:

צריך אתה לידע שארץ ישראל סמוכה למערבו של עולם הרבה מכל הארצות

[8] See here. See also here. How pre-modern people imagined the world, which was based on the maps they saw, has relevance to the question of where to place the halakhic dateline. See e.g., the important articles, complete with historical maps in color, by R. Dovid Yitzchoki and R. Efraim Buckwold in Tevunot 2 (2018), pp. 969-1095.

[9] See also Rashi, Shabbat 145b s.v. הני. In the Soncino translation to Shabbat 65b the following note appears: “Obermeyer, p. 45 and n. 2 rejects this [Rashi’s opinion] on hydrographical grounds, and explains that in most cases the rains in northern Mesopotamia in the Taurus range, where the Euphrates has its source, are the precursors of rain in Palestine.” The book by Jacob Obermeyer referred to is Die Landschaft Babylonien im Zeitalter des Talmuds und des Gaonats: Geographie und Geschichte nach talmudischen, arabischen und andern Quellen (Frankfurt, 1929).

[10] The term “Holy Land” with reference to the Land of Israel is actually not mentioned in the Bible, the Talmud, or the geonic writings. According to Hayyim Asher Berman, who has investigated the matter, the term in its Hebrew version first appears in the medieval period. Berman also notes that the Zohar uses the term ארעא קדישא hundreds of times. Berman claims that it is actually due to the Zohar’s use of this term that the Hebrew version became so popular. See Ha-Ma’yan 61 (Tevet 5781), pp. 102-103. (Understandably, others will see this as another sign that the Zohar was written in the medieval period.) Berman’s investigation was spurred by R. Shaul Yisraeli’s rejection of the term “Holy Land,” which he saw as a Christian invention in opposition to the term “Land of Israel.” R. Yisraeli noted that unlike ארץ הקודש, the term אדמת קודש is a Jewish expression and relates to the many mitzvot relevant to the Land of Israel. See R. Meir Schlesinger, “Hirhurim al Hibat ha-Aretz,” Ha-Ma’yan 60 (Tamuz 5780), p. 50. R. Yisraeli was obviously aware that the term“Holy Land” was often used by Jews for the last thousand years. However, I believe his intention was about the present, not the past. Today you can find Christians who speak of visiting the Holy Land and are careful to never actually mention the name “Israel.” This has to be seen for what it is, an anti-Zionist delegitimization of the existence of the State of Israel.

[11] See also Tosafot, Kiddushin 71b. s.v. עד.

[12] See R. Jacob Emden’s note to Arakhin 15a where he criticizes Tosafot for a geographical mistake that was also due to not having a reliable map:

ואמנם כל מ“ש תוס‘ כאן אינו נכון גם ציור הארצות והים הוא מתנגד למציאות

To this I would add R. Meir Mazuz’s melitzah: אין אחר המציאות כלום (The expression is based on Bava Batra 152b [end]: אין אחר קנין כלום)

[13] See e.g., R. Elijah Mizrahi, Commentary to Genesis 32:2. In his super-commentary to Nahmanides, Gen. 38:18, R. Menahem Zvi Eisenstadt writes:

הדברים קשים להולמם, שהרי צדקו דברי רש”י שא”י בדרום ארם היא, והדבר ידוע

[14] The Soncino translation says as follows: “The Hebrew Hoddu is really ‘Indus,” and refers to the north-western portion of the Indian peninsula which was drained by the Indus. This territory was added to the Persian Empire by Darius.”

[15] To the sources listed there, see also Tosafot Yom Tov, Yoma 3:7, who does not make the connection between the

נ in הינדואה and the dagesh in the ד of הדו.

[16] See

Avodah Berurah, Sukkah, vol. 2, p. 128.

[17] See his note to

Megillah 11a.

[18]

Perush ha-Torah le-Rabbenu Avraham ben ha-Rambam, ed. Moshe Maimon, vol. 1, p. 150.

[19] See here.

[20] “Toponomy of the Targumim,” (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Oxford University, 1974), p. 134.

[21] The issue of the Zohar’s knowledge of the Land of Israel has been discussed for a long time. Gershom Scholem, in his article on the Zohar in the

Encyclopaedia Judaica, writes as follows: