Rav Shmuel Ashkenazi: a Hidden Genius

Rav Shmuel Ashkenazi: a Hidden Genius

By Eliezer Brodt

This Monday night is the first yahrzeit marking the passing of a unique Talmid Chacham, R’ Shmuel Ashkenazi of Yerushalayim, at the age of ninety-eight. R’ Shmuel was one of the hidden giants of the seforim world, in both ultra-orthodox and academic circles. I had the Zechus to learn much from him and in this article, I wish to describe this fascinating but hardly known Gaon and what we can learn from his life. An earlier abridged version of this article appeared in the Ami Magazine last year. IY”H in the future I will expand this essay.

One day back in 2000, while learning in the Mir as a Bochur, I was having a conversation with a friend, R’ Yaakov Yisrael Stahl, and R’ Shmuel Ashkenazi’s name came up, R’ Yaakov described him as an extraordinary Talmid Chacham. A little while later, during one of my daily seforim store trips I noticed a recent arrival, a very heavy sefer (844 pp.) with a peculiar title, Alfa Beta Kadmita de-Shmuel Zeira. I opened it up and immediately put two and two together, realizing that the author is the same R’ Shmuel Ashkenazi I just heard about. Upon purchasing it, I could not put it down. Learning through it I was immediately able to tell that my friend had not exaggerated in the slightest way. It appeared that this person knew literally everything about anything connected to Torah.

First Meeting

At the time, I had been working on researching and publishing my first article which dealt with tracing everything about the custom of not sleeping on Rosh Hashanah. One of the earliest sources quoted was in the name of a Yerushalmi which appeared to have been lost at some point. I had been searching all over for any information on this topic, and it was then that I noticed that R’ Ashkenazi was planning on writing about this topic in the next volume of his. I am not sure why but at the time I did not make an effort to speak with him about this. I returned to the US for a few years, and while in the US I drafted a letter to him listing all of my issues on this topic but I never got around to sending it. When I returned to Eretz Yisroel in 2004, one of the first of my planned stops was to visit R’ Shmuel Ashkenazi. Almost immediately upon returning a newly made friend, R’ Duvid Vieder, a Toldos Aharon Chossid who was close to R’ Ashkenazi, brought me into him to visit. From then on, I began to visit him regularly, this custom continued until a few weeks before the 2020 coronavirus lockdowns. At times I visited him once a week for an hour or so, other times once a month, other times I would speak to him on the phone.

I must preface my reminiscences by saying that, sadly, I did not heed the advice of the Chasam Sofer who told his children and talmidim that since he won’t be around forever, they should “chap arein” and listen to his stories. Unfortunately, this is not the first person with whom this has happened to me. I took for granted that Rav Ashkenazi would be around forever, (he did die at the age of 98!) and assumed I would always be able to ask him again for a particular story or an idea that he mentioned.

What was the connection?

Basically, each visit I would prepare lists of questions to ask him. I would also bring him new seforim or articles (printed out in big letters, to help him read it easier). Sometimes when I would ask him something, he would say he is old and his head does not work, other times it was amazing what he remembered – on the spot. Sometimes he would pull down a file of material stored in – no jokes here – old cornflakes boxes.

I would then scan some of the material. Other times he offhand did not have anything to add on a particular topic but when looking at a particular sefer I would find a note written on the side or in a paper stored in the sefer that would be related to what I was searching. Other times I would find something else which was of great importance. Rarely did I leave his house empty handed. We both shared a love for seforim and information on a wide range of topics.

Love of Seforim

What drew me to him, and particular developed my relationship with him, was our shared love of seforim. I would update him on new seforim. At times he would ask me to purchase it for him or would borrow my copy for a bit. He told me numerous times how he enjoyed visiting and buying seforim from various shops for many years and that he started collecting when he was seven years old! Now he could not go to stores as he was too old; I got to know him when he was over eighty.

When I joined the editorial board of the journal Yeshurun, I would bring him each new volume as it was printed. Each visit he would ask me to check on the shelf where he kept them, to see if he was up to date and if needed, to update him with any missing volumes. A true lover of seforim, his face would lit up at each new volume. I would then point out some of the articles I thought he would enjoy and he would put in markers to read them.

I always wondered if he read the various volumes of Yeshurun I brought him. After he was niftar, while going through his seforim, I found inserted in one rare book a small paper which he wrote: “for more information about this author see the article in Yeshurun”. Then in a different pen he added another cite from another issue from Yeshrun from a few years later.

This small story also demonstrates a bit of his methodology; he would collect all kinds of information and store them at times in a related sefer and would constantly update these notes.

His love for seforim was something unique, the glow on his face when he opened up a new sefer, especially of someone he was into, was simply priceless. He would look carefully at the Shaar and if it was a reprint of an older sefer he would immediately check if they included the front page of the older edition to compare. He had seforim in every space possible in the four rooms of his apartment, including his porch. Many visitors noticed how even his kitchen was lined with seforim!

Dikdueki Sofrim Haskomot

An interesting story happened with me and his library. While working on an article about the Dikdueki Sofrim I was unable to track down some recorded Haskomot that the author R’ R.N.N. Rabinowitz had received for the first edition of his work. I, along with other scholars, had searched numerous copies of the first edition, but with no luck. Late one night, I came to R’ Ashkenazi’s house and mentioned to him my problem. He said “show me the issue inside,” keeping with his custom to take care to always view the source material firsthand (Osiosi Machkemios – a topic he wrote a lot about). I took down his copy of the sefer, and lo and behold it was a first edition with the missing Haskamot! I published these missing Haskamot in my article on the Didukei Sofrim, and attributed this rare and miraculous find to his extraordinary library.

His History:

Where this unique Talmid Chacham came from is simply a mystery. He was born in Yerushalayim and lived in Batei Ungarn. He learned by Rav Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky of the Edah HaChareidis. Originally, his name was Deutsch but, at some point changed it to Ashkenazi. He had four children with his wife who died over forty years ago. Since then, he lived alone in his apartment near some of his children. His son did an excellent job of Kibud Av bringing him food every day and looking on him a few times a day. Yom Tov and Simchos he spent time with his family.

When I and others asked him, who was his Rebbe, he would just smile and say no one in particular. The truth is the Mishnah in Avos states: Knei Lecha Chaver. Aside from the simple peshat, Rashi explains this Mishnah by citing some who say it means via Seforim others commentators explain this as ‘buying a pen’ (see R’ Ashkenazi’s in-depth article on this for sources). R’ Ashkenazi employed all of these methods; his friends and teachers were his seforim and his pen.

R’ Ashkenazi was a short, quiet and unassuming person. Most, having seen him walking on the street, would never believe he was such an erudite Gaon. Many times, R’ Ashkenazi did not express much emotion except to give a pleasant smile and was friendly and polite in conversation. But there were times he got very excited; for example, when he recalled a good story from his younger years or something unique that he discovered years ago. He was very polite and was a real Yekeh; for example as soon as they bentched Rosh Chodesh Kislev his Menorah was already prepared in the window.

R’ Yechiel Goldhaber, a Talmid Chacham and author of numerous articles and seforim had a close relationship with R’ Ashkenazi for many years. He recalled when he was introduced to R’ Ashkenazi for the first time by his father-in-law, he thought to himself who is this simple looking man? He soon learned that this man was a master of all of Torah and swiftly became a close Talmid of his.

Many times, he would tell me he wishes he could come visit my library. In Later years he would spend his Yomim Tovim at his daughter. One Chol Hamoed Succos, when he was over ninety, he made the difficult trek from her house to mine in order to spend time in my library.

He would love to read everything he could get his hands on. I visited him at many different times of day, even late at night and I always found him learning a sefer – even when he was over ninety. He read everything newspapers, books – he was just curious about everything with an incredible thirst for knowledge.

I recall visiting him a few times when he eighty-five and noticed he was learning the Shelah Hakodosh very carefully. I asked him why (of course he had learned through this sefer numerous times before!) and he responded that someone is reprinting the sefer and asked him to go through the sefer and send comments. He therefore sat down to learn the whole sefer, line by line, after which he wrote a ten-page letter with his comments on the sefer.

Over time, I learned again and again that R’ Ashkenazi personally believed his purpose in this world was to help people with the incredible amounts of information that he had gathered over the years of intense learning. This incredible Middah can be seen in this light; he did not feel that he was the “owner” of this extraordinary wealth of information he had collected, and thus gave very willingly without any conditions. He never asked me to cite him when he gave me some rare source even – although I always told him I would; he just was so happy to help someone else.

He would collect and catalog much of what he read. He had all kinds of systems to file the information he had gathered over eighty plus years of learning. When he would read an important article in a magazine or journal, he would cut out the parts and store them in their appropriate place. He gathered information on thousands and thousands of subjects (not an exaggeration in any form) which had some connection to our rich heritage. What’s more astounding is that R’ Ashkenazi never used a computer or the internet; all of his erudition came about simple by learning through thousands of seforim; a great many of them rare or unknown.

Over the years he helped so many people and for many years after he retired, he would visit the National Library of Israel on Tuesdays, where throngs of people would line up in wait to speak with him about all kinds of subjects.

Many years ago, he received a call from a young chassidish Talmid Chacham living in Monsey who was starting to work on publishing a new edition of the classic historical work Seder Hadorot. He started asking him questions about various issues he had. Over many phone-calls R’ Ashkenazi answered many of his difficulties while training him in proper research and writing skills. This year some volumes finally were published (see here). And this was not a onetime occurrence – he helped so many more people. He used to remark to me that when he was younger so many people would come to visit him – until the late hours of the night.

He was an expert in so many different topics, whether it was the standard ones like Tanach, Chazal, Halacha, Minhag or Chassidus or less commonly studied subjects such as Tefilah, Piyut, Dikduk, Kabbalah, Philosophy, Machshavah, History and Bibliography. In all of these areas his expertise was remarkable.

His Uniqueness

A sample of his bekius; one time I noted that the Maharsha often quotes a “Sefer Yoshon Noshon” and asked if we have any idea which sefer this is? He immediately responded that he found it usually refers to R’ Todros Abulafiah’s Otzar Hakavod.

His incredible Bekius was bolstered by an almost photographic memory, as the following story demonstrates. Once someone used the Bar-Ilan Responsa search engine to locate a passage in the Tana DeBei Eliyahu to no avail. He went to ask R’ Ashkenazi who immediately told him where the passage could be found. Checking the Bar-Ilan text, it was discovered that when the sefer was being entered into their database the passage in question had been mistakenly omitted. I first heard this story from someone else, so to make sure it was accurate I asked him about it and he confirmed it. A similar story happened with him and a passage from the Shut Chasam Sofer.

A few years back a friend was working on publishing out an esoteric Rishon on Mesechet Megillah. He thought no one ever heard of this author and randomly mentioned this to R’ Ashkenazi – without batting an eyelash – replied “of course, and one can find material by this author in the work of Rav Shlomoh Alkabetz on Megillas Esther (Manos Halevi). The fellow was stunned in elation; he had just been gifted new and important material for his project.

This remarkable Bekius which even beat out computer search engines, was just one aspect that made him remarkable. He would receive numerous calls and letters from all over the world from people of all walks of life seeking his assistance in tracking down a statement. He had an incredible knowledge of all of Chazal. I do not just mean the “standards”; Bavli, Yerushalmi and Midrash – even all the numerous and very often almost unknown Midrashim printed over the years. He was also expert in what is known as the lost Midrashim. Over the years many Midrashim we had were lost but some traces of them can be found in various Piyutim, cited by Rishonim or in other obscure places. Through his incredible amounts of learning and his phenomenal memory he was able to recall so much in this field.

To illustrate this with some samples. A few years back someone who was editing for publication a never before printed pirush of a Rishon on Avos came across a few statements in the name of Chazal. This person, a Talmid Chacham in his own right and familiar with tracking down such material, could not locate sources for these statements. Immediately he penned a letter to R’ Ashkenazi. A few days after he received a letter from R’ Ashkenazi with various incredible sources for his questions. This was a very common occurrence.

Piyut, Tefilah and language

Earlier, I mentioned his expertise in Piyut, Tefilah and language. A bit of background is needed to explain this. Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, when describing Rabbi Elazar Hakalir’s greatness, (Koren Mesorat Harav Kinot (pp. 386-388) wrote the following:

The piyutim of Rabbi Elazar HaKalir, including his kinot, serve two purposes. The first is limmud, learning. Every sentence of the piyut quotes m’aamarei Chazal… The second purpose is tokhaha, rebuking the people for their misdeeds and instructing them in the proper way to act. These piyyutim deal with… repentance… acknowledgment of God’s justice. The shali’ah Tzibbur was not merely a chazan…, but was one of the great scholars of the generation who was the principal… moral critic of the people… Rabbi Elazar HaKalir was (also) a master of the Hebrew language and very creative in his use of Hebrew. If not for him, modern Hebrew could not have come into existence. Before HaKalir, the Hebrew language was very rigid. For example, the noun and verbs were fixed in their form… But HaKalir made a critical contribution to the development of the Hebrew language by endowing the language with flexibility… Rabbi Elazar haKalir’s piyutim served two purposes: limmud, study… As for the element of study, one of the dimensions of HaKalir’s piyyutim is that they are compilations of the statements of the sages. Most of us, who are expert in neither Hebrew nor aggadot Hazal, find HaKalir’s corpus of piyutim boring. But it is not boring at all; it is like a gold mine. His piyutim for Yom Tov explain the essence of the Yom Tov. The midrashim concerning Sukkot are replete with information about the sukka, etrog and lulav, and all the explanations in the Midrash, all the ta’amei sukka, the reasons for the sukka, all of the ma’amarei Hazal, are together in the HaKalir’s piyutim for the first day of Sukkot… If one were to study carefully and thoroughly the piyutim of Rabbi Elazar HaKalir for Rosh HaSahana, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, and Pesah, one would find many applicable halakhot and the entire pertinent Midrash, including many midrashim that are unknown to us from any other source.

Rav Ashkenazi was an expert on everything related to Tefilah and Piyut. He somehow read it all and retained it. But in addition, he was able to use his expertise in Chazal and Hebrew language to understand it on a much higher level and as a result was often contacted by the world experts on Tefilah and Piyut for his assistance. These requests came from experts such as Professor Shalom Speigel, Chaim Schirmann, Avraham Haberman, Ezra Fleischer and Daniel Goldschmidt who constantly sought his assistance while working on their Tefilah and Piyut related projects.

In an interview with Ami Magazine printed a few years back, Professor Shulamit Elitzur mentioned:

“there’s another amazing thing I find when doing research. I am constantly coming across midrashim that were lost to the ages… example, everyone knows that Haman was referred to as ‘the Agagi’ because Shaul allowed Agag to live one extra night, which allowed Haman’s ancestor to be born. However, the earliest makor we find in writing in the 16th century; this fact was discovered by Rav Shmuel Ashkenazi of Yerushalayim. But I found a ktav yad of a piyut about Purim that describes this very story and explains how Haman’s ancestor was born, which gives us a source from 1,000 years earlier! And there are many similar examples of lost midrashim being kept alive through unknown piyutim.”

R’ Ashkenazi wrote some articles on Piyut and Tefilah, but we have found much more among his papers and hopefully if I can raise enough funding all his fascinating material on Tefilah will come to light.

When the important Siddur Ezer Eliyahu (sponsored by his late friend Yeshaya Vinograd) was first printed, one can see R’ Ashkenazi’s name in the introduction, thanking him for his assistance (he assisted them for some of the later additions) and his great knowledge in this field.

I mentioned that he had an incredible knowledge of Dikduk and the Hebrew language and used it towards better understanding Piyut and Tefilah. He also authored articles on these subjects and in 1967, when reviewing an important dictionary, wrote a long article demonstrating this very point – and article that garnered much praise. He was very proud of this essay and mentioned it to me many times. A few years ago, I reprinted it with additions he had made in his own copy and a nine-page topical index.

One of the ways he developed this expertise was via learning Tanach so many times. He was an expert in Tanach and all the Rishonic commentaries (including the unknown ones); he even authored a small book of Riddles of Tanach.

He also used his extraordinary skills to become a master editor. However, in addition to the work he was born with an incredible innate sensitivity for text and language which made him one of the best editors out there. For many years he worked at the famous publishing house Mossad HaRav Kook, editing various works. He told me more than once how there was an expert there who would brag (jokingly) that after he read through an article it was impossible to find mistakes. The only person who could still find mistakes was R’ Ashkenazi. He had razor-sharp vision and could immediately spot a mistake.

Many times, I would bring an edited piece of mine to read. As soon as I put it down in front of him, he would take out a red pen and start marking it up and say to me “are you sure it’s been edited?”. He told me he had to mark up everything before he could read it properly, errata were so painful for him to see that it was hard for him to read something on Shabbos! He told me he was punished; when his work Alfa Beta Kadmita de-Shmuel Zeira came out, although he had edited it numerous times, he still found mistakes.

During his learning over the years, he found many people, great Gedolim as well as famous academics, had made mistakes, sometimes quite basic ones. At one point he printed two articles about this. However, he prefaced his articles that his intent was not to mock those who erred but to vividly illustrate that people are human and mistakes will happen. He was a master of humility and never held it over anyone that they did not know what he knew.

He was not only a great expert in all aspects of the Hebrew language but was an expert in Aramaic and Yiddish, both of which he displayed in various publications of his. Related to his expertise in Aramaic, which is very important for learning Gemara, is a very unique essay which he authored related to the Rambam as a translator of the Gemara. One of the world experts in old Yiddish is Professor Chava Turniansky, who has noted on many occasions that one of the people who have always helped her from her days as a student, was R’ Ashkenazi.

Related to this was another talent of his, which at first appears trivial; he was an expert on acronyms. This led to authoring a thesaurus of acronyms together with Dov Yardan, called Otzar Roshei Tevot, with a multitude of obscure and often almost impossible entries. His sensitivity to the text and work in the field of editing drew him to this field. Anyone who learns a lot, especially older material comes across abbreviations, and many times they cause great difficulty in understanding various passages. Abbreviations were employed in writing, sometimes as mnemonic devices and other times simply to save on printing costs. But over time many meanings were forgotten. This work is an extremely useful tool for solving this issue.

Ghostwriting

One day I was in a used bookstore and I noticed a small sefer titled Harif Umishnaso about the Rif. I recalled that this title appeared in the list in beginning of his work, Alfa Beta Kadmita de-Shmuel Zeira which listed out the various works he helped with over the years. I asked R. Ashkenazi if it’s worth buying and what his connection to the book was, as a different name appears on the cover.

R’ Ashkenazi replied “I can tell you it’s an important sefer and worthwhile to buy.” I noticed he was hesitant to continue the conversation. He then said “I will tell you something I did not tell anyone in over forty years – I wrote the whole sefer from beginning to end and it was one of the most important works I ever wrote.” The original plan was to for him to write a series of biographies on various Rishonim – in this book he already references a work on the Ri Migash – but due to a lack of funding this series was discontinued. However, not all of this remained unpenned; he wrote numerous entries in various encyclopedias. It turns out that R’ Ashkenazi had over fifteen different pen names!

I would like to elaborate on this work a bit more and thus cast further light upon R’ Ashkenazi’s uniqueness and greatness. The Rif’s Halachic work is one of the most important sources in Halacha, but what exactly makes it so unique has remained a mystery. R’ Ashkenazi sought to answer this question by collecting and collating all the authentic information we have about the Rif, from the Rif and from other Rishonim. He went through the Rif carefully examining what he did to each Gemara evaluating if remarks or material was added or not and to figure out why, allowing the reader to begin to understand the Rif’s significance. R’ Ashkenazi’s writing methods were honed to precision. He had an uncanny ability to utilize every piece of information without writing an extra letter and assemble it all in perfect order sans speculations commonly found in historical works. At times one does not need grand theories to understand something; just seeing all the known material in proper order helps one understand things. The wealth of material that Rav Ashkenazi commanded in producing this work is outstanding; this book was written in 1967 – long before any of the various search engines used today.

Haggadah Sheleimah

Similar to this is another work by R’ Ashkenazi, Haggadah Sheleimah. I hope to publish an article about this work in the near future, including the numerous additions R’ Ashkenazi found over the years and kept in his files. This work is highly unique for the following reasons. The collected bibliographies by Avraham Ya’ari and Yitzchak Yudlov bear witness to thousands of Haggados written throughout the generations in a multitude of styles, such as Pilpul, Peshat, Kabbalah, Derush and more. However, until 1955 there was no one work on the Haggadah which collected all the sources for each and every Halacha and minhag related to the Seder night. There was no volume which dealt with the various manuscripts of Geonim and Rishonim and at the same time to deal with the exact text of the Haggadah. Haggadah Sheleimah set out to fill those needs, and at the same time offer a running collection of Pirushim culled from over fifty different commentators focusing just on Peshat. In order to produce such an exacting work, it’s not good enough to just be a talented writer, one must also possess a keen understanding of all the material and relay this with incredible clarity. R’ Ashkenazi was such a person; one who sought out the simple Peshat, able to put this myriad of information together in so beautiful a fashion, and with tremendous clarity. His work in Haggadah Sheleimah is so clearly organized and always straight to the point that it is no wonder that to this day Haggadah Sheleimah remains a classic in both the Torah and Academic worlds.

Rav Ashkenazi once explained to me that one has to write precisely and to the point, not lengthily. He said he believed that one of the reasons Rashi’s works survived was due to his concise way it was written, as opposed to various works of Geonim which did not really survive as they were written in a much lengthier format.

Why didn’t he publish his material?

A few years ago, a partial bibliography of his writings was printed in his Alfa Beta Kadmita de-Shmuel Zeira. The listing is close to three hundred articles and seforim that he wrote or assisted in on some level. He started writing under various pen names over eighty years ago. The background to the publication of this volume was, as I mentioned previously, R’ Ashkenazi had been writing and collection information on thousands of topics for over eighty years. Unfortunately, he did not print much of what he gathered. The main reason for this was R. Ashkenazi’s “weakness”; he demanded incredible levels of perfection from himself. Although he strived for great perfection, nonetheless he stressed to me numerous times that he was mistaken in that approach and that I should not follow in his path. In his words it is better I print my work to the best of my current abilities and that worse comes to worse you can always reprint with additions and corrections. Over twenty years ago, R’ Teflinsky somehow convinced R’ Ashkenazi that his material needed to be printed. Together they began compiling some of his material for print, resulting in a volume over eight hundred pages!

After that experience both R’ Ashkenazi and R’ Teflinsky stopped, with no plans of continuing this project. A few years later my good friend, R’ Yaakov Yisrael Stahl and myself were able to convince him to continue. R’ Stahl took upon himself the daunting task to prepare the material for publishing; since, than three more volumes were printed.

Here is a small video clip of R’ Ashkenazi, when we brought him copies of the second and third volumes of his writings, ten years ago.

The topics that these works deal with cover, on some level, virtually everything; sources for expressions and idioms, for minhag, Halacha, the evolution of famous stories, bibliography, corrections of authors’ errors, encyclopedic style information on thousands of topics culled from thousands of seforim – many of them very rare or unknown. (A PDF of the Table of contents of this work is available upon request).

His Letters

Earlier I mentioned the story of someone who wrote him a letter seeking help. This was not a one-time occurrence. He authored well over a thousand such letters in response to such questions. Some requests were for sources to various Halachos or Minhagim, numerous others are various queries related to out rich literature. R’ Ashkenazi always invested his time to answer properly and clearly. Recently, R’ Stahl and I collected these letters for publication and the result is a three-volume set, available for purchase.

Over seventy years ago he purchased a typewriter which he used until his passing.

In an article written by the late Gaon R’ S. Deblitsky, he writes out various proper actions a Rav should “observe.” One of them is to respond to people who write to him, whether the issues are big or small. R’ Ashkenazi was very careful to try to respond promptly. Many people would send him their seforim after they were printed asking him for his comments. He would usually respond with a multi-page letter, beginning by thanking the author for sending it to him, then listing out some criticisms, usually written delicately, while adding all kinds of comments. He always tried to look to say something positive. Some people who heard of him through various channels over the years contacted him before they printed their works. Many times, he would write a collection of comments and corrections to such works. A sample listing of some of those works that benefited from him before going to print include recent editions of: Sefer Zechirah, Kav Hayasher, Sefer Hachayim and many others.

Thanks to the efforts of my special friend Menachem Butler, various academics wrote some praises about the significances of these letters; to partially quote one letter written by the esteemed Professor Shnayer Z. Leiman:

Reb Shmuel was

“bibliographer, bibliophile, and book collector, and his encyclopedic knowledge of all of Hebrew and Yiddish literature remains unparalleled in our time.” His collected writings are an intellectual treasure trove, “covering a wide range of topics in the field of Jewish Studies. Aside from his scholarly distinction, R. Shmuel Ashkenazi wrote in an elegant Hebrew with its own special charm. Not only did he advance discussion, but he did so in an aesthetically pleasing manner. Let it be said openly: this… set will enlighten every reader and will significantly advance scholarship. Anyone concerned with advancing the cause of quality Jewish scholarship will take special delight in the publication of these volumes…During his lifetime [Ashkenazi] corresponded with the greatest Jewish scholars and bibliographers the world over. They wrote to him, for only he could solve the countless historical and literary problems that stumped them…”

Another person to whom Menachem Butler reached out to via his numerous contacts was former editor of Mekizei Nirdamim’s journal Kabez Al Yad, Professor Shulamit Elizur of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In her aforementioned interview in Ami Magazine several years ago she said this:

“I am unequal to the task of adequately singing the praises of Rabbi Shmuel Ashkenazi, an erudite bibliophile. His familiarity with rabbinic writings from throughout Jewish history is unparalleled, and he is well-versed in the research literature of academic Jewish studies as well. I first met Rabbi Shmuel Ashkenazi through my teacher, the late Professor Ezra Fleischer. Prof. Fleischer, who was one of the greatest scholars of all time, would often chat with Rabbi Ashkenazi on scholarly topics, and he was careful to send Ashkenazi every article or book he published, knowing that in return he would receive enlightening comments on his work. When I began my own research, Prof. Fleischer instructed me in turn to send my publications to Rabbi Ashkenazi, and I too was privileged to learn a great deal from his comments. It once happened that I was searching for a particular midrashic theme which was alluded to in a liturgical poem (piyut), and although I consulted the leading scholars of Jerusalem who responded that it was a well-known homily, I was unable to locate its specific source. In my hour of need, I turned to Rabbi Ashkenazi, who immediately gave me several references. It emerged that every one of these references post-dated the piyut by almost a thousand years, and that this ancient tradition alluded to in the poem had been transmitted orally for that long period before being committed to writing in the later midrashim. Rabbi Shmuel Ashkenazi’s correspondence is a tremendous resource of Torah and scholarship. Every paragraph encapsulates a great deal in just a few words, and sometimes even with allusions whose explication require deep learning.”

Here is a short letter from Professor Gershom Scholem to R’ Ashkenazi:

Expressions and famous stories

In his writings some of the topics of these are about tracing expressions or the evolution of famous stories. Based on his knowledge, he was able to contribute a lot to these areas even editing some works on these topics.

One such story related to a supposed legend of a portrait of Moshe Rabbeinu which caused a great controversy over a century ago. In 1830, Rav Yisroel Lipschutz started printing his magnum opus, a commentary on the Mishnah titled Tiferes Yisroel. In the section on Maseches Kiddushin first printed in 1843, he brings a story about a king who lived in the time of Moshe, who, after hearing incredible things about this great leader, hired a painter to paint a picture of him so he could have his features analyzed by experts. The people who analyzed the picture reported that the person pictured was evil. The king went in person to visit Moshe Rabbeinu in the midbar and asked him how was it that an analysis of his pictures showed him to be of such wicked character. Moshe told him that the analysis was indeed true; however, after much work, he changed his character and became the great Moshe Rabbeinu.

In 1894 a booklet by the Vilkomir Maggid was printed railing against this story. This booklet presented numerous sources stating that Moshe Rabbeinu was born a kadosh and it was unthinkable to print such a story about him. Indeed, this story was censored out of the 1956 edition of the Tiferes Yisroel. In truth, this ancient legend can be found in various sources and in regard to different luminaries, some claiming it about Aristotle others, Socrates. In fact, R’ Ashkenazi documented it was long used in various Musar and Chasidus sefarim cited as an important lesson that one can change one’s born nature for the good, but not that it actually was true about Moshe Rabbeinu.

Another such story relates to a famous legend about the site where the Beis Hamikdash was built. Told in short, two brothers inherited a field, one brother had a family one did not. At the end of the harvest they divided up the wheat equally. That night the childless brother felt bad for his brother with a large family and said to himself “it’s unfair that while my brother needs more than I, we shared equally”, so he brought over from his pile to his brothers. The other brother thought that since his brother was childless, he should have a larger share of the crop, as consolation, so he added from his share to his brother’s. In the morning each brother realized their piles remained the same and this went on for two more nights. On the third night they met, realized each of their intentions was out of deep consideration for the other and hugged. Numerous people have searched for the early sources for this story. I decided to ask R’ Ashkenazi if he had any material on the subject. He found his file on the story and within was a letter from R’ Yudlov who had been asked by someone in the Education Ministry for the sources on this story. R’ Ashkenazi traced its first appearance in print to 1832 and from there he traced it to other sources.

Bibliography

I would like to conclude with just one more area in which R’ Ashkenazi was truly a legendary master: Bibliography. For many years, R’ Ashkenazi worked in the (now) National Library’s Bibliography of the Jewish Book Project. He also contributed to some of the important bibliographical works and journals written in the past century such as Kiryat Sefer, Otzar Sefer Haivri (Vinegrad) and Sifrei Yerushalyim Harishonim.

A few years back, while working on an article about the origins of eating Hamantaschen (see here), I found an important article from Dov Sadan containing sources on this topic. One of the sources was the interesting, controversial work Machberet Emanuel. I had a nice conversation with R’ Ashkenazi about this work – he had helped Dov Yardan prepare a critical edition of the work and even wrote a long book review on it (which he said he received a lot of Kovod for).

He mentioned two points of interest which will serve as a sample to some of his expertise. One, he noted that Emanuel of Rome wrote a commentary on sefer Mishlei. Interestingly, the preface to the Mishlei commentary sefer is signed Emanuel son of Yaakov, whereas Emanuel’s father’s name was Shlomo. Some have noted that this discrepancy and explained it is a mistake. R’ Ashkenazi suggested this was not a mistake, rather an intentional typo intended by the author to hide his connection to his controversial Machberes Emanuel. The second point he made to me was how the Chida writes in Shem Hagedolim that the best commentary to learn on Mishlei that by Emanuel of Rome. R’ Ashkenazi said he checked into the words of the Chida and he learned through all the works on Mishlei and concluded that the Chida was quite correct. He once had a dream to write a whole work on Mishlei, he even started to pen his comments in a special notebook, but the plans never worked out.

One final last story about R’ Ashkenazi’s bibliographic acumen. In 2009 my special friend Dr. S. Sprecher z”l (about him see this article on the seforim blog here) wished to reprint and distribute a small work called Tshuvah Be’Inyan Kriat HaKetubah, in honor of his son’s upcoming wedding, under that assumption that, just as the title page and the publisher’s introduction indicated, it represented an actual Halakhic Responsum issued in 1835 by the Chief Rabbi of Bialystok, one Rabbi Nechemiah. Sprecher wrote:

However, our close reading of this Tshuvah led us in an entirely different direction. To us, the work’s style manifested clear Maskilic echoes, and its arguments rejecting the binding nature of centuries-old Minhagim were clearly not in accord with 19th–century Halakhic thought. Our reaction was that the work must certainly be pseudepigraphal and could not have arisen from the pen of the Chief Rabbi of Bialystok. In fact, a quick perusal of the reference literature demonstrated that there never was any Chief Rabbi of Bialystok named Nechemiah.

At an impasse, we reached out to Professor Shnayer Z. Leiman, who suggested that the scholar most likely to solve the mystery would be the doyen of Israeli bibliographers, Rabbi Shmuel Ashkenazi. We were rewarded thanks to the tireless efforts of Eliezer Brodt who, on our behalf, pestered the aged Jerusalem sage until he successfully unmasked the name, but not quite the identity, of the author. Rabbi Ashkenazi concluded that the first line of the introductory poem that prefaced the Halakhic query contained the acrostic – “Meir Ish-Shalom”. (His initial contention was that this could not be the noted 19th–century Viennese scholar, Meir Ish-Shalom, because his heretofore known literary output began only some five years later, with his publication of the Sifre in 1864.)

Once Rabbi Ashkenazi had provided the key to the author’s name via the acrostic, it became apparent that all along the title page had been proclaiming that very same message. Let us recall the passage in Bavli Eruvin 13b where it is recorded that the celebrated Tanna, known to us as Rabbi Meir, was actually named Nehorai, according to one opinion; or alternatively, that both Meir and Nehorai were laudatory appellations reflecting his enlightening wisdom, whereas his actual name was Nechemiah. Recall also that the query first originated with Rabbi “Shalom” of Novgorod, and the word “shalom” appears twice more on the title page and is highlighted by the placement of a circle above one of its appearances.

In his copy of this work that Dr Sprecher printed for the Chasunah which I brought him, I found this paper inside:

A few weeks after R’ Ashkenazi’s Petirah the national library held a session devoted to him where Professor Zev Gries, Professor Chava Turniansky and R’ Yechiel Goldhaber spoke about him (here is a link to the whole session). I too had the privilege of being interviewed about him that night (Here is a link to my interview).

Publication of his writings

Last year, immediately after Rabbi Shmuel Ashkenazi was niftar I, along with my special friend Menachem Butler, initiated a campaign to raise funds to publish R. Ashkenazi’s letters via the Seforim blog. Baruch HaShem, and thanks to the help of some readers, enough money was raised to go to print and in the beginning of this past January copies of the book, coming in at over 1,700 pages, (three volumes!) arrived as announced (here). The Letters sold out in a few days. A second edition was printed right before Pesach (see here). Currently copies of the second edition are available for sale.

Future volumes

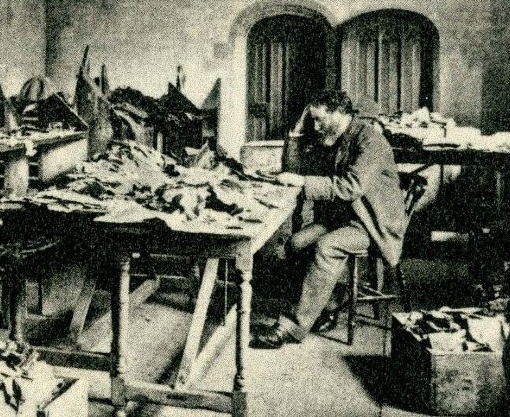

Already during the Shivah, R’ Stahl began going through the materials of R’ Ashkenazi to sort out what materials are print worthy.

Here is a picture of R’ Stahl taken during one such session which a friend of his humorously put side by side a famous picture of Solomon Schecter when working on Geniza documents.