The Haftarah of Parashat Shemot

The Haftarah of Parashat Shemot[1]

By Eli Duker

The Babylonian haftarah for Parashat Shemot was from Ezekiel 16: “Hoda’ et yerushalayim.”

The haftarah appears in at least six fragments from the Cairo Geniza,[2] is the haftarah used in the “Emet” piyyut of R’ Shemuel Hashelishi[3] and in the “Zulat” piyyut of R’ Yehuda Beirabbi Binyamin,[4] and is listed in the Seder Hatefillot in Rambam’s Yad Hahazakah as well as in the Siddur of R Shlomo Beirabbi Natan.[5]

This haftarah, an extremely graphic and difficult prophecy, was chosen because it begins by describing the Egypian enslavement and the Exodus. In all of the fragments that describe where the haftarah ends, the last verse is verse 16:15, likely so as not to continue with the difficult words of rebuke that follow that do not have anything to do with the parasha. The Baylonian custom allowed for haftarot that were less than twenty one verses even if the subject is left uncompleted because they still had the practice to read Jonathan’s Targum along with the haftarah, and thus were exempted from the twenty-one verse minimal requirement, as per the ruling of R’ Tahlifa bar Shemuel (Megilla 23b).[6]

This choice of haftarah seems to be problematic in light of the Mishna (Megilla 4:10):

מעשה ראובן נקרא ולא מתרגם מעשה תמר נקרא ומתרגם מעשה עגל הראשון נקרא ומתרגם והשני נקרא ולא מתרגם ברכת כהנים מעשה דוד ואמנון נקראין ולא מתרגמין אין מפטירין במרכבה ורבי יהודה מתיר ר’ אליעזר אומר אין מפטירין (יחזקאל טז, ב) בהודע את ירושלם.

The Mishna brings, without dissent, the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer, which forbids this haftarah. However, the Tosefta as it appears in MS Vienna National Library Heb. 20 seems to allow this haftarah, while Rabbi Eliezer’s view is brought as a dissent:[7]

הודע את ירושלם נקרא ומתרגם ומעשה באחד שהיה קורא לפני ר’ ליעזר הודע את ירושלם אמ’ לו צא והודע תועבותיה של אמך.

However, according to that same Tosefta as it appears in MS Berlin Staatsbiliothek Or. Fol. 1220, the Tanna Kamma merely permits haftarot with general rebuke directed at Jerusalem (תוכחת ירושלים), while Rabbi Eliezer objected to the particular choice of Ezekiel 16:

תוכחת ירושלים נקרא ומתרגם ומעשה באחד שהיה קורא לפני ר’ ליעזר הודע את ירושלים ואמ’ לו צא והודע תועבותיה של אמך.[8]

Like the Mishna above, the Talmud Yerushalmi brings Rabbi Eliezer’s prohibitive opinion regarding this haftarah, and presents no other view:

ר’ אליעזר אומר אין מפטירין בהודע את ירושלם את תועבותיה מעשה באחד שהפטיר בהודע את ירושלם את תועבותיה אמר לו ר”א ילך אותו האיש וידע בתועבותיה של אמו ובדקו אחריו ונמצאו ממזר.[9]

The following appears in both printed versions of the Talmud Bavli [10] as well as in three manuscripts of the Bavli:

הודע את ירושלם את תועבותיה נקרא ומתרגם פשיטא לאפוקי מדרבי אליעזר דתניא מעשה באדם אחד שהיה קורא למעלה מרבי אליעזר הודע את ירושלם את תועבותיה אמר לו עד שאתה בודק בתועבות ירושלים צא ובדוק בתועבות אמך בדקו אחריו ומצאו בו שמץ פסול .

This is very difficult to understand. How can the Gemara assume (פשיטא) that this haftarah can be read if the Mishnah already brought Rabbi Eliezer’s unchallenged opinion forbidding it?

Accordingly, two other manuscripts do not have the word פשיטא.

For example, MS. Columbia 294-295 has the following:

הודע את ירושלם את (..)[ת]ועבותיה נקרא ומיתרגם ומעשה באחד שקרא לפני ר’ אליעזר הודע את ירוש’ את תועב’ אמ’ לו צא והודע תועיבות שלאימך עד שאתה בודק בתועבות ירושלם צא ובדוק בתועבות אמו בדקו אחריו ומצאו בו שמץ פיסול.

Here, the story with Rabbi Eliezer is brought within the context of the view of the Tanna Kamma that it is permissible to read this haftarah. Rabbi Eliezer clearly does not reject this view outright, but still deemed this haftarah a poor choice and an inappropriate one at least under the circumstances.[11]

All of the other manuscripts besides this one feature an explicit disagreement between the Tanna Kamma, who permits this haftarah, and Rabbi Eliezer, who forbids it. The Gemara rejects Rabbi Eliezer’s opinion.

Communities that followed the triennial cycle of the Torah reading never read the beginning of Ezekiel 16 as a haftarah. However for the sidra of V’atta Tetzaveh, they did begin the haftarah from Ezekiel 16:10.[12] It could very well be that this haftarah was deemed permissible despite the Yerushalmi’s ban on the preceding prophecy due to the fact that they held a view later cited by the Levush[13] that the problem with Ezekiel 16 is not the severity of the rebuke but but merely verse 16:3, “Your father was an Amorite and your mother a Hittitess,” which was referenced in Rabbi Eliezer’s retort, seemingly because it casts aspersions of the kind with which no one would be comfortable.

In Europe there were two alternative haftarot for Parashat Shemot: Jeremiah 1:1 and Isaiah 27:6. It seems that many communities either did not want to read Ezekiel 16 even though it was allowed by Halacha because of the weight of Rabbi Eliezer’s rejection, or because they had versions of the Talmudic sources which unanimously presented the haftarah as permissible but undesirable.

In the Iberian peninsula, there were communities that retained the haftarah of Ezekiel 16. It is brought as the haftarah for Parashat Shemot by the Sefer Hashulhan, which was authored by Rabbeinu Hiya ben Shlomo ibn Habib, a student of the Rashba. However, R’ Shemuel Hanagid’s list of haftarot in Sefer HaEshkol lists Jeremiah 1 as the haftarah of Parashat Shemot. The same can be found in Sephardic haftarah books in manuscript[14] and in Sephardic lists of haftarot found in the Cairo Geniza.[15] The reason for this choice of haftarah is the parallel between Jeremiah’s first prophecy and that of Moses. Abudarham lists both of these practices, although it is unclear whether he meant that they were both read in Sepharad or whether he had other locales in mind.

In an early printed humash that is assumed to be Spanish and from around the year 1480, the haftarah for Parashat Shemot is Jeremiah 1:1, while the Hijar Humash from 1487-90 (the only dated humash with haftarot printed before the Expulsion) has Ezekiel 16 as the haftarah.[16] It would be at least over two hundred years later before any other humash was again printed with this as the haftarah.

The Italians adopted Jeremiah 1 as the haftarah for Parashat Shemot as well[17] which is quite surprising, as they preserved more Babylonian haftarot than any other community.[18]

In Ashkenaz, France-England, and Provence the practice was to read Isaiah 27:6 as the haftarah for Parashat Shemot. The same was used as the haftarah for the sidra of V’Eila Shemot in the triennial cycle of Eretz Yisrael.[19] This haftarah was chosen due to its literary rather than thematic associations with the Torah reading, as was generally the case with the rest of the haftarot read according to the triennial cycle. (The haftarot favored in the annual cycle were chosen for their thematic content.)

The first verse of the haftarah,הבאים ישרש יעקב יציץ ופרח ישראל parallels the first verse in the sidra: ואלה שמות בני ישראל הבאים מצרימה את יעקב איש וביתו באו. Three of the haftarah’s first six words are in the first verse of the sidra.[20] We also find that the Romaniote community, which often adopted haftarot from the triennial cycle, adopted Isaiah 27:6 as the haftarah for Parashat Shemot.[21]

This haftarah is also attested to in the Ginzburg manuscript of Mahzor Vitry, in Sefer Etz Haim, in the Sefer HaEshkol’s glosses on the Nagid’s list (where it begins at 27:5, one verse earlier), and in all Ashkenazic humashim and sifrei haftarot in manuscript (although three of them also begin the haftarah one verse earlier).[22]

This haftarah was read in some Morrocan communities.[23]

There were different practices regarding the end of this haftarah. In some manuscripts the final verse is 28:13 making it a “classic” haftarah of exactly twenty one verses, especially appropriate as it was never read with its translation by any community using the annual cycle. Some, in order to end on a clearly positive note, would skip from 28:13 to 29:22 and read two more verses. This is how it appears in all printed humashim with Ashkenazic haftarot. In other manuscripts, we find an alternate practice of extending the reading to verse 28:16, instead of skipping to a later point.

The ensuing printed humashim with Sephardic haftarot post-Expulsion all listed Jeremiah 1 as the Sephardic haftarah for Parashat Shemot

In spite of its absence from the printed humashim, Ezekiel 16 was still retained by many communities as the haftarah for Parashat Shemot. This created a bit of difficulty for those communities. In the recently published Kaf Naki, R. Khalifa Malka, who was active in Agadir, Morocco, between c. 1720-1760,[24] wrote:[25]

The early Magreb practice, as well as our practice, is to read for Parashat Shemot the haftarah of “Hoda’,” based on the Rambam at the end of Sefer Ahava. It is proper to act this way, as he is the rabbi of the Sephardim and the Magrebim. Also concerning this haftarah,[26] I requested of the printer, R’ Shlomo Proofs, to print it together with the haftarah of Hoda’…and he did this to please me in the humashim that he published later on, which had not been done in the days of the publishers who preceded me.[27]

I have not been able to locate any such humashim.[29] The first printed post-expulsion humash I was able to find with this haftarah was printed in Jerusalem by Zuckerman in 1866.

Besides Agadir, this haftarah was (dare I say, miraculously,) retained in many places in various Medditerian and Middle Eastern communities including Algiers,[29] Tafilalt,[30] Fez,[31] Libya,[32] Djerba,[33] Persia/Bukhara,[34] Yemen, and Baghdad.[35] In order to deal with the fact that it did not appear in printed humashim, the practice in Baghdad was to print this haftarah along with the haftarah from Isaiah they would read for Parashat Bo (that was not commonly featured in many printed humashim[36]) in special “Nokh” booklets which had lists of verses and selections from the Mishna that would be recited at home on Shabbatot.[37]

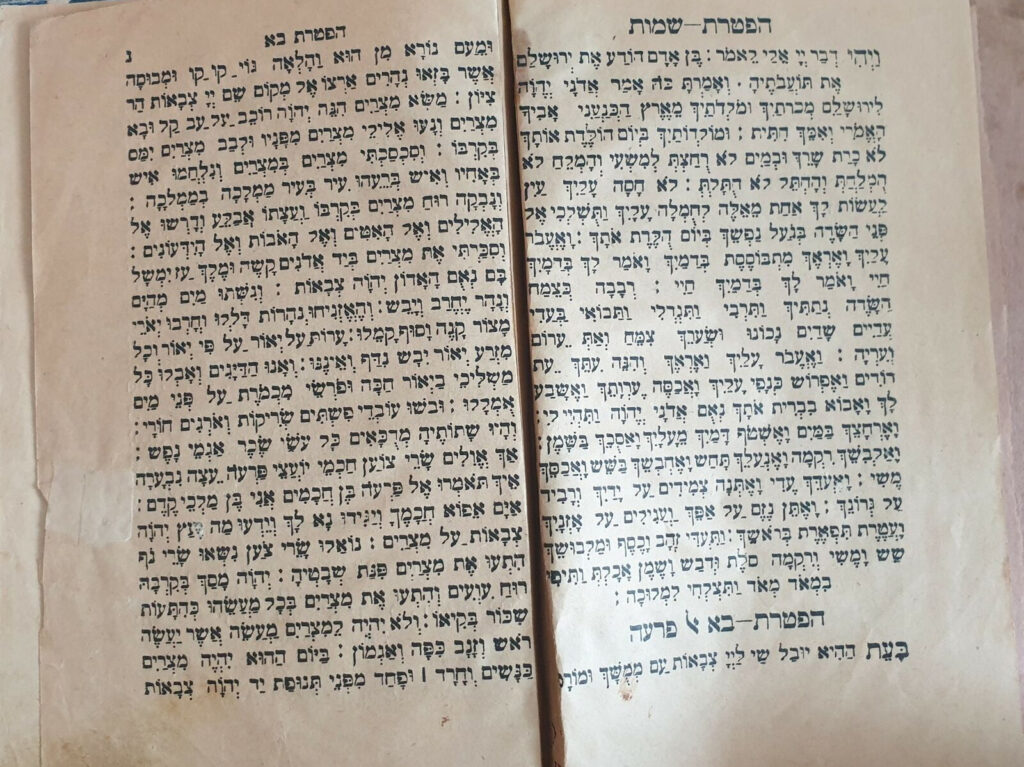

Nokh booklet with the haftarot for Shemot and Bo according to the Bavli custom. (Baghdad, 1930)

[1] I would like to thank Rabbi Avi Grossman for editing this.

[2] Cambridge T-S A-R A13, T-S A-S 19.241, T-S B14.54, T-S B14.62f, T-S B15.5, T-S B20.4

[3] The Yotserot of R. Samuel the Third, Yahalom and Kastuma ed., Vol. 1, pg. 294-295.

[4] Piyyutei R’ Yehuda Beirabbi Binyamin, Elitzur ed., P. 136.

[5] Siddur Rabbeinu Shemuel Beirabbi Natan Hagi ed. Pg. 200.

[6] See Teshuvot Hageonim, Sha’arei Teshuva 84, in the name of R Hai.

[7] Megilla 3:34

[8] See Tosefta Kifshuta, Part V, pg. 1216

[9] Megilla 4:12, This is the version in MS Leiden and all printings of the Yerushalmi.

[10] Vilna, Venice 1520-3, and Pesaro 1509-17.

[11] See Hiddushei HaRan there for an explanation as to why he objected in spite of its permissibility.

[12] See Ofer’s list at https://faculty.biu.ac.il/~ofery/papers/haftarot3.pdf

[13] Levush Hahur 478. See also Duker, Hahaftarot Lefarashiyot Aharei Mot UKdoshim L’fi Minhag Ashkenaz in Hitzei Gibborim Vol. 11, pg. 387-498.

[14] PARM 2054 and Angelica Rome 55.

[15] Cambridge T-S B20.2 and T-S B20.14

[16] Based on this and the Sefer Hashulchan, it could be that the retention of that haftarah was an Aragonian practice

[17] MS Parm 2169.

[18] Besides from retaining the original haftarot for Bo, Behar, and Behukkotai, the Italians only read the special haftarot of Destruction and Consolation during the month of Av, but not in Tammuz or Elul, thus retaining the Babylonian haftarot for the parashiyot of Matot, Masei, Shoftim, Ki Tetzei, Ki Tavo, and Nitzavim. The fact that, unlike as in other communities, the Italians did not read Jeremiah 1 on the Sabbath following the Seventeenth of Tammuz, may indicate that the practice of reading Jeremiah 1 as the haftarah for Shemot originated in Italy, but this is just conjecture at this point.

[19] Ibid. Ofer’s list.

[20] Heard orally from Prof. Yosef Ofer.

[21] See Fried list in the back of Encyclopedia Talmudit Vol. 10

[22] The haftarah appears as such in Geniza Fragment Cambridge T-S B16.19b as well. It is also the haftarah in the “Emet” piyyut of R’ Shelomo Suleiman al-Sinjari, but he vacillates between using haftarot from the Babylonian custom and the haftarot from the triennial cycle. See The Yoserot of Rabbi Selomo Suleiman al-Sinjari for the Annual Cycle of Torah Reading. Hacohen, ed. Pg. 368-370.

[23] Naziri, Otzar HaMinhagim VeHamesorot LiKhillot Tafilalt V’Sijilmasa pg. 84 footnote 128, and Danino, Miminhagei Yahadut Morocco. Avaialble at http://www.daat.ac.il/daat/toshba/minhagim/mar-tfi.htm. Avitan, Minhagei Halacha Lefi Kehillot Morocco., link. The fact that Isaiah 27:6 was read as the haftarah for Parashat Shemot in Morocco opens up the possibility that this may have been the practice somewhere in Spain prior to the Expulsion. Moroccan communities retained all three of the haftarot that we have for Parashat Shemot, as Jeremiah 1 was read in Sefrou (Naziri, ibid.) and is still read today in at least some communities that follow Morrocan practices. Others read Ezekiel 16, as discussed below.

[24] Published 2012, Orot Yehudei HaMagreb, Halamish M. ed.

[25] I would like to thank Rabbi Yehoshua Duker for translating this.

[26] Referring to Isaiah 19 as the haftarah for Parashat Bo.

[27] He proceeds to claim that it had not been printed due to the influence of the Levush which, (in his opinion,) was influential because of the dearth of other works on the Shulhan Aruch back then. I think it is merely because the haftarah was not printed in the Venetian humashim published by Bromberg (in particular, the 1524 edition), which had a heavy influence on the selection of haftarot in later humashim. I will address this in an article on the haftarot of Vayetze and Vayishlach that I hope to publish soon.

[28] He clearly saw the humash with these haftarot as he wrote about how the last verse of the haftarah for Shemot was left out.

[29] Zeh Hashulhan, Minhagei K”K Algier p. 245

[30] Naziri, pg. 84

[31] Ibid. footnote 128 quoting Sefer Ahavat HaKadmonim pg. 6a. It is also written there that this was the practice in Izmir and Turkey.

[32] Biton, Nahalat Avot, p. 65

[33] HaCohen, Brit Kehuna, pg. 16.

[34] Zuckerman Humash

[35] Sitbon, Alei Hadas, pg. 360.

[36] It was only printed in humashim with Italian haftarot (before the late 20th century) such as the following: Manitoba 1589, Amsterdam 1712 (Proofs), 1729 (Binyamin ben Uri Katz), and Venice 1820.This list not exhaustive.

[37] Simanei Pesukei Nokh, 1920. A complete listing of the various printings (seven in all) can be found in Ben Yaakov, Minhagei B’nei Bavel B’Dorot HaAharonim.