Pandemic Bibliopenia: A Preliminary Report of Disease Eradication

אין חכמת אדם מגעת אלא עד מקום שספריו מגיעין[1]1

ר‘ יצחק קנפנטון

(ואין ספריו מגיעין בשעת המגיפה[2])

Pandemic Bibliopenia:[3] A Preliminary Report of Disease Eradication

Rabbi Edward Reichman, MD

The number of seforim written during, about or related to the Covid 19 pandemic continues to grow at breakneck speed.[4] What has largely gone unnoticed among the other unprecedented aspects of this pandemic, is that since the development of the printing press, we have not seen so much quality rabbinic literature produced in the midst of a pandemic.[5] In fact, if anything, a diminution in the quantity and quality of literature was more the norm during previous pandemics. This literature proliferation during Covid 19 heralds in a new age and reflects the eradication of a common condition prevalent in the premodern era- Pandemic Bibliopenia (heretofore, PB).

Few alive today have previously experienced a pandemic of the magnitude of Covid 19. While those Torah scholars and bibliophiles who weathered pandemics of the past would surely have been familiar with PB, possibly even from personal experience, the scholars of today are simply unfamiliar with this condition and have likely never seen a case. Furthermore, we are unlikely to see many cases of PB in the future as well (see “treatment” section below).

Since cases of PB in the present and future are likely to be exceedingly rare, the possibility of misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis is therefore a significant concern. We therefore review this condition and some illustrative cases to record its history for posterity, lest we completely forget this previously incurable disease that afflicted the Jewish community for centuries.

Definition/ Diagnosis

Pandemic

adjective

Associated with a widespread outbreak of a contagious disease.

Bibliopenia

noun

Biblio- relating to a book or books

Penia (suffix)- lack or deficiency

A lack or deficiency of books

Pandemic Bibliopenia (PB) is defined as the lack or deficiency of books available to scholars during times of widespread disease.[6] This often leads to quantitative or qualitative decline in literature produced during times of plague or pandemic.[7]

Etiology

While the Talmud explicitly recommends one to shelter in place during times of plague,[8] the practice evolved from at least the late Middle Ages and onwards to flee the urban areas for more rural, less densely populated locations.[9] Access to rabbinic works was often severely limited, if existent at all, in these remote areas. Production of literature was thus severely hindered or curtailed in areas of disease. Plagues often lasted for many months or longer.

Literary Manifestations

PB appears to be more explicitly manifest in halakhic, specifically responsa, literature, with less impact on other genres, such as poetry,[10] or other forms that do not require or rely heavily on texts. Halakhic writing often requires referencing a wide spectrum of legal writings. Furthermore, due to the often-urgent nature of halakhic queries, the response cannot await the passing of the pandemic. Elective works, however, can simply be delayed until calmer times, when access to libraries, be they private or public, can be restored.

Epidemiology

The impact and prevalence of PB throughout history is difficult to assess,[11] though it has likely been significantly underreported. Cases can only be definitively identified from manuscripts and printed works where PB is explicitly mentioned. One of the primary manifestations of Pandemic Bibliopenia is the unwritten book. How many works were conceived, and perhaps even gestated, though not birthed as a result of PB? As this is manifestly impossible to quantify, as no evidence of such remains, we will thus never know the extent of the bibliographic mortality of PB throughout history.

PB shows no innate predilection for age, gender or geographic location and is associated solely with the presence of pandemics.

Case Studies

There are a number of possible presentations of PB.

Severe Cases of Pandemic Bibliopenia

Below are two clear cases of severe PB.

- Rabbi Yom Tov Tzahalon (c. 1559-1638)[12]

Rabbi Yom Tov Tzahalon (known as Maharitz) authored a number of halakhic works in the late sixteenth-early seventeenth centuries and lived in Tzfat for part of that time. There were a number of plagues in Tzfat during this period. In Tzahalon’s responsa we see clear evidence in a number of places of his affliction with Pandemic Bibliopenia.[13]

Siman 8

Due to plague in Tzfat, Tzahalon was forced to flee from mountain to mountain, village to village, and states explicitly that he lacks sufficient access to works of poskim to answer the question properly. He nonetheless offers a limited response to appease the questioner.

Siman 19

Tzahalon again notes his lack of access to rabbinic literature in the midst of plague, including the tractates of the Talmud, with the exception of tractates Bava Kama and Bava Metzia, and a portion of Rambam.

During the writing of the above responsum Tzahalon resided, albeit temporarily, in Kfar Par’am, located to the Northeast of the city. People generally fled to villages on the outskirts of their city of residence.

(the pin represents Par’am)

Siman 44

During the writing of this responsum Tzahalon appears to have returned to wandering between villages and once again laments his inability to provide an in depth and expansive response.

Siman 81

In our final, albeit less explicit, example of PB in Tzahalon’s responsa, written in 1589, Tzahalon bemoans his prolonged exile and the toll it has taken, though does not allow this to prevent him from offering a halakhic analysis of the issue.

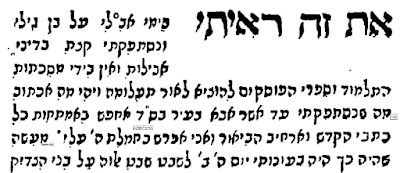

We not only have mention of Pandemic Bibliopenia in Tzahalon’s responsa, it also surfaces in his Talmudic commentary.[14] Tzahalon wrote his commentary on the fifth chapter of Bava Metzia, at least partially, while in exile. Parenthetically, this may explain why the only volumes of Talmud he possessed in exile were Bava Kama and Bava Metzia, as he likely packed these specific tractates for his travels anticipating work on his commentary. In the midst of his Talmudic commentary[15] we are introduced to Tzahalon’s personal tragedy while in exile in Kfar Par’am with the following line:

Tzahalon digresses from his commentary to share the details of the tragic death of his infant son.[16] The timing of the death, associated with a delayed burial, precipitated a halakhic question for the author:[17] Here again he reiterates his lack of access to required Talmudic tractates and poskim. He writes of his intent to review and expand his analysis upon his return to the city and to his library after the cessation of the plague.

Of note, while this passage is physically situated in the midst of this Talmudic commentary, it is in essence a halakhic responsum.

- Rabbi Hayyim Palachi (1788-1868)[18]

Rabbi Palachi was the Chief Rabbi of Izmir in Turkey. During his lifetime a cholera pandemic affected Turkey. In a number of his works he acknowledges suffering from Pandemic Bibliopenia. An explicit reference is below:

Hikikei Lev, vol 2, H. M., n. 51, p. 164a

Palachi was exiled to the village of Boron on the outskirts of Izmir. While lamenting that there is “no wise man without seforim,” he endeavors to respond to a halakhic question with the resources he has available him in addition to relying on his memory. Below we see the repeated mention of PB throughout multiple works reflecting a most serious case of the condition.[19]

Hikikei Lev, vol 1, E. H., n. 57, p. 114b

Hayyim Biyad n. 79, p. 98a

In a letter to Rabbi Hayyim Yehudah Avraham, published in the latter’s Ahi vaRosh[20] Palachi writes while still in exile in the village of Boron:

Varied Prevalence of PB

In the following case, we see the clear impact of PB on one Torah scholar, while another scholar during the very same pandemic appears to enjoy immunity from the condition.

In perhaps our most poetic example, Rabbi Yehudah Ibn Verga[21] corresponds with Rabbi Yosef Karo, author of the Shulhan Arukh, about a financial matter.[22] After lengthy praise for Rabbi Karo, he launches into a lament about the current state of plague in Tzfat.

Ibn Verga’s invokes the same phrase from Tehillim[23] (nikhsifah vigam kaltah nafshi) as does Tzahalon (Siman 81 above) to express the emotions evoked by the plague. His comment at the end of this passage about his elation upon meeting another person in the midst of the plague will sound familiar to those of us who have weathered complete lockdown during the current pandemic.

The next passage reflects the duration of Ibn Verga’s exile. Ibn Verga remarks that his exile had passed the entire summer, now into the winter, and the plague still lingered. “We have said, it is long due to the sins of the generation.” Ibn Verga and Karo both lived in Tzfat. Ibn Verga had hoped to speak to him directly about this case, face to face, but as the plague dragged on, he had no recourse but to commit his comments to paper.

Ibn Verga concludes that he had wanted to cite a responsum of Rosh in support of his position but was unable to include it due to his affliction with PB.[24]

In his response, Rav Yosef Karo likewise longs to speak face to face with Ibn Verga:

He concurs that sin has caused them to be in a state of “mistar panim” until the plague passes. Rabbi Karo then proceeds to discuss the halakhic issue and makes no mention of lack of access to literature. He also lived in Tzfat and endured the same plague. In fact, we know Rabbi Karo fled Tzfat during the plague to live in the village of Birya.[25] It is in Birya in 1555 that he completed the first volume of his Shulhan Arukh. While the Shulhan Arukh was only first printed in 1565 in Venice, the colophon of each volume reflects the date and place of its completion.

Colophon at end of the 1565 edition of the first volume of Shulhan Arukh:

By the time he had completed the second volume, Yoreh De’ah, less than one year later, he had already returned to Tzfat, presumably after the cessation of the plague.

Colophon at end of the 1565 edition of the second volume of Shulhan Arukh:

While Rabbi Ibn Verga was clearly a victim of PB, Rabbi Yosef Karo does not appear to have been affected whatsoever. We thus have evidence of the variable prevalence of the condition during the same pandemic.

Mild or Implicit PB

Some cases of Pandemic Bibliopenia are not as explicit or easily diagnosed as those of Rabbis Tzahalon and Ibn Verga. At the same time as the aforementioned were experiencing plague in Northern Israel, Rabbi Moshe Isserles faced advancing disease in Cracow. Rabbi Isserles describes his dire situation in the introduction to his Mehir Yayin, a commentary on Megilat Esther that he wrote for his father-in-law, in lieu of mishloah manot, while in exile in the city of Shidlov.

While Rabbi Isserles does not explicitly refer to Pandemic Bibliopenia, he makes passing references possibly alluding to the condition. For example, he writes:

which means that his intellect still remained, despite his lack of access to an extensive library.

In describing the work, he writes:

Perhaps PB is reflected in his choice of composition, a work relying heavily on his textual analytic skills, and less so on obscure or hard to obtain texts, likely unavailable to him in Shidlov.[26]

Furthermore, his qualifying statement,

might reflect a lack of bibliographical resources. Whether this case meets the diagnostic criteria for PB remains a question.

Differential Diagnosis

Pandemic Bibliopenia may possibly be confused with other forms of Bibliopenia. To be sure, many individuals have lost access to their libraries due to personal tragedies,[27] but here I refer specifically to systemic forms of Bibliopenia that impacted entire communities. In these cases authors were similarly deprived access to rabbinic literature, though for entirely different reasons. One such example will suffice.

The Physician Abraham Portaleone was a prominent figure in Renaissance Italy, treating royalty, authoring several medical works.[28] At the age of 62 he suffered a stroke which prompted a reevaluation of his life. He concluded that his affliction befell him as he had not devoted enough of his life to Torah learning. He undertook to write a work on prayer and the Beit HaMikdash which he dedicated to his children. At the end of chapter thirty-two, which discusses the shulhan in the Temple, we find the following comment.

Portaleone notes that, “Perhaps some place in the Talmud Hazal spoke of this, and I am not aware. As a result of the known deficiency [my emphasis] I have not been able to properly ascertain this.”[29] One might erroneously assume that he is referring to Pandemic Bibliopenia as the etiology for his lack of access to the Talmud. In fact, Portaleone is referring to a variant form of the condition, called Censorship Bibliopenia. A review of the entire work of Portaleone, including his introduction, will clarify any confusion.

In his introduction, Portaleone details the nature of his early education, and recalls how while a student studying Talmud with R’ Yaakov MiPano, the infamous decree led to the Talmud “being consumed by fire before our eyes.” This refers to the burning of the Talmud in Rome in 1553.[30] After the initial burning of the Talmud in Rome, other Italian cities followed suit with their own citywide burnings. Portaleone was witness to one such event. Decades later, as he penned his classic work, Shiltei haGibborim, the Talmud still remained largely unavailable in Italy. Portaleone was forced to use substitute works that alluded to or quoted the Talmud, if available, but sometimes the information was simply not accessible. One such example is his discussion of the Shulhan above.

In one remarkable instance Portaleone reveals his elation at being able to acquire a bona fide Talmudic reference. He writes that after he completed the chapter on the Lishkat haGazit (Chamber of Hewn Stone), God ordained (hikra) that he happen upon a wise man from the city of Tzfat (where the Talmud was available) who had come to Italy to seek financial support for his family. “From his mouth I heard the sugya in the second chapter of Yoma on the laws of the Lishkat haGazit, and I write them here for you (my children) from his mouth…”[31]

In yet another place he excitedly relates of his accessing a small passage from Tractate

Chagigah from a tattered manuscript remnant in the library of a great Torah scholar (Gaon) of Verona.[32] All of these instances are examples of Censorship Bibliopenia.

Treatment

During previous pandemics, in the pre-modern era, PB was considered untreatable. Fortunately, however, it was temporary and ultimately resolved with the cessation of the pandemic. Today, however, the treatment for PB is readily available and inexpensive, though its safety has been called into question. Despite the fact that the understanding of disease transmission has evolved, people still, if feasible, flee their homes in urban areas for less populated locations. As such, they could still be susceptible to PB. However, PB is now completely remediable through internet access to Rabbinic literature.[33] Not only is virtually the totality or rabbinic literature widely and freely available for scholars (rabbis, poskim and laymen) via the internet, facilitating the production of quality work; the publication and dissemination of these works can be accomplished with ease on the internet as well. It is only today, in the midst of the current Covid 19 pandemic, that we are witnessing the eradication of PB. As a result, there have likely been more pages written of rabbinic discourse (both halakhic and aggadic, related to the pandemic or not) during the present pandemic than during all previous pandemics combined.[34]

Conclusion

Pandemic Bibliopenia is an underrecognized phenomenon in Jewish history. In addition to the medical impact of pandemics in the past, our ancestors experienced spiritual and intellectual suffering by being deprived access to the Torah library, our life blood. Today, however, even in the midst of a worldwide pandemic, while libraries have shuttered, and some have fled their homes, there has been little diminution in the access to rabbinic literature. As the world may never again experience Pandemic Bibliopenia and the unique literary impact of plagues and pandemics, it behooves us to recall it in appreciation that despite the many adversities associated with this pandemic, loss of access to our beloved Torah literature is not counted among them. Not only have we eradicated Pandemic Bibliopenia, it appears to have been replaced with a new diagnostic category, Pandemic Polybiblia,[35] though in this case, fortunately, a healthy and desired condition. May we be zokheh to the continuation of Polybiblia without any associated pandemics in the future.

[1] Isaac Canpanton (15th century), Darkei HaGemara. This oft quoted phrase refers specifically to the purchase of one’s own seforim. I take literary license with its use here.

[2] My addendum.

[3] This condition has been variously called epidemic or plague bibliopenia. We use the term pandemic in light of the present Covid 19 pandemic.

[4] See Eliezer Brodt, “Towards a Bibliography of Coronavirus-related Articles and Seforim written in the past month (updated), Black Weddings and others Segulot,” Seforimblog.com (May 4, 2020).

[5] The proliferation of literature specifically related to the pandemic is also noteworthy and unprecedented but is not the focus of this article. On the history of literature written during times of plague, see Abraham Yaari, biOhalei Sefer (Reuven Mass, 5699), 82-90. The other essays in this volume chronicle the impact of various natural occurrences, such as fires, and personal experiences, such as imprisonment, miraculous salvation, or infertility, on the writing of Hebrew books.

[6] The etiology may be related to either closure of public libraries, which is a more widespread form PB, or due to required or elective relocation away from one’s personal library to remote areas devoid or deficient of seforim.

[7] Plague and the migration to the rural areas affected not just the writing, but the printing of Hebrew books as well. See Yaari, op. cit.; Avraham Haberman, Perakim biToldot haMadpisim haIvrim (Reuven Mass: Jerusalem, 5738), 314.

[8] Mishnah Ta’anit 3:4.

[9] See Yaari, Moshe Dovid Chechik and Tamara Morsel Eisenberg, “Plague, Practice and Prescriptive Text: Jewish Traditions on Fleeing Afflicted Cities in Early Modern Ashkenaz,” Journal of Law, Religion and State (2017), 1-27. I thank professor Susan Einbinder for bringing this article to my attention.

[10] For poetry in times of plague, see Susan Einbinder, After the Black Death: Plague and Commemoration Among Iberian Jews (University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, 2018). idem, “Poetry, Prose and Pestilence: Joseph Concio and Jewish Responses to the 1630 Italian Plague,” in Haviva Yishai, ed., Shirat Dvora: Essays in Honor of Professor Dvora Bregman (Ben-Gurion University: Beer Sheva, 2019), 73-101; idem, “Prayer and Plague: Jewish Plague Liturgy from Medieval and Early Modern Italy,” in Lori Jones and Nükhet Varlik, eds., Death and Disease in the Medieval and Early Modern World: Perspectives from Across the Mediterranean and Beyond (York Medieval Press, 2021), forthcoming.

[11] We do not address here the impact of disease and illness on literary output.

[12] On Tzahalon, see, Shimon Vanunu, Arzei Halevanon (Jerusalem, 5766), 862-865; Shalom Hillel “Sefer Magen Avot– Rabbeinu Yom Tov Tzahalon” Mekabtziel 33 (Kislev, 5768), 10. Vanunu lists all the references discussed below.

[13] Here we do not address the substance of the responsa, rather focus on the impact of PB on the author. I mention the responsa in number order, assuming this is chronological.

[14] Tzahalon’s Talmudic commentary was first published by his grandson in Venice, 1693, where it appears after the former’s responsa. A corrected and annotated version of the Talmudic commentary was published by S. Mertzbach in Benei Brak in 5752.

[15] This was written in the manuscript in the middle of his commentary on the fifth chapter of Bava Metzia, but is printed separately as n. 14 as part of his responsa.

[16] His son’s death does not appear to have been plague related, as he recounts that his son was perfectly healthy just prior to his death.

[17] The delayed burial generated a question for Rabbi Tzahalon as to which day was considered his first day of mourning and thus whether he should put on tefillin.

[18] On Palachi, see Shimon Aryeh Leib Eckstein, Toldot haHabif (Halevi’im Press: Jerusalem, 5759). All of the citations mentioned he are referenced on p. 183, n. 17.

[19] See also his Nishmat Kol Hay, vol 2, E. H., siman 3, page 6.

[20] (Izmir, 1840), H. M., n. 14, p. 88b.

[21] This Yehuda Ibn Verga is not to be confused with the Spanish historian and kabbalist of the fifteenth century.

[22] Rabbi Yosef Karo, Avkat Rokhel, 99 and 100.

[23] 84:3.

[24] If I am reading this correctly, it seems that Ibn Verga was still in Tzfat when he wrote this but had sent his library ahead to his location of exile.

[25] See R. Ephraim Greenblatt, “B’Inyan Kiddush Levanah,” Noam 12 (5729), 113. Birya can be seen on the map above, between Tzfat and Par’am.

[26] This work does reference texts from the Talmud and Tanakh as well as the Rambam’s Moreh Nevukhim. These may have been his available texts.

[27] See, for example, Yehuda Rosenthal, “ The History of the Jews in Poland in Light of the Responsa of the Maharam of Lublin,” (Hebrew) Sinai 31:7-12 (Nisan– Elul, 5712), 320 regarding Maharam miLublin and his limited access to his library due to a fire in Cracow.

[28] On Portaleone, see H.A. Savitz, “Abraham Portaleone: Italian Physician, Erudite Scholar and Author, 1542-1612,” Panminerva Medica 8:12 (December, 1966), 493-5; S. Kottek, “Abraham Portaleone: Italian Jewish Physician of the Renaissance Period- His Life and His Will, Reflections on Early Burial,” Koroth 8:7-8 (August 1983), 269-77; idem, “Jews Between Profane and Sacred Science: The Case of Abraham Portaleone,” in J. Helm and A. Winkelmann (eds.), Religious Confessions and the Sciences in the Sixteenth Century (Brill, 2001); A. Berns, The Bible and Natural Philosophy in Renaissance Italy (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

[29] End of Chapter 32.

[30] See Menachem Butler, The Burning of the Talmud in Rome on Rosh Hashanah, 1553 theTalmud.blog (September 28, 2011).

[31] Chapter 23, p. 109.

[32] For discussion of these cases, see Y. Katan and D. Gerber, eds., Shiltei haGibborim (Machon Yerushalayim, 5770), 28-29.

[33] See Jacob J. Schacter, “The Challenges and Blessings of the Internet: Technology from An Historical Perspective,” Jewish Law Association Studies, vol. 29 [The Impact of Technology, Science, and Knowledge] (2020), 5-20. Rabbi Dr. Schacter highlights some striking parallels regarding challenges created by the development of printing and the development of the internet.

[34] I admit being guilty of contributing to this phenomenon.

[35] The diagnostic criteria for this new entity have not yet been adequately formulated and will require a fuller evaluation with the passage of time. A preliminary definition has been proposed: The proliferation of rabbinic works relating to pandemics written in the midst of the pandemic itself.