The Twice Told Tale of R’ Yonasan Eybeshutz and the Porger[1]

Moshe Haberman

Moshe Haberman currently lives in Los Angeles and is a businessman. Originally from New York, he learned in Brisk and publishes the Torah journal Chitzei Giborim.

Introduction

The only Halachic sefer[2] published in the lifetime of R’ Yonasan Eybeshuts was the ספר כרתי ופלתי which is a פירוש on Shuchan Aruch Yoreh Deah, dealing with issues of treifos, basar b’chalav, taaruvos, etc. The sefer was published in 1763, a year before his death in 1764 in Altona, which at that time was in the dominion of the King of Denmark.

In his preface to כרתי ופלתי, R’ Yonasan explains that he had already written other seforim, including Urim Vtumin, B’nei Ahuva, and Ya’aros Dvash. However due to the difficult situation he found himself in over the controversies regarding Kameos ascribed to him, that were allegedly Sabbatean in nature, he felt it was impolitic to publish his works earlier in his lifetime. He also shied away from getting the approbations customary upon the publication of a work, and כרתי ופלתי was published without any haskamos.

Despite the seriousness of the Sabbatean allegations, there is no doubt that he was considered to be a genius in Torah, and his influence over his many students was immense. His works are widely used by later generations of Halachic decisors; in many halachic issues, his views are considered normative.

In סוף סימן ס’ה, which is focused on the issur of Gid Hanasheh, the “displaced” nerve that is not allowed to be eaten, he discusses a story illustrative of how difficult the removal of the nerve can be, ie. Porging. There was someone considered to be a Talmud Chochom and expert in porging that claimed that the nerve that the general practice to remove was in actuality the wrong one, and he was being taken seriously in the German communities. When he came to Prague, he met with R’ Yonasan, who was the acknowledged Posek in this field, and (as R’ Yonasan relates the story) he was told by R’ Yonasan that he was wrong, the nerve that this expert was referencing was only found in male animals and not in female animals. R’ Yonasan showed him in the Semag[3] that Gid Hanashe applies to males and females. Apparently this expert accepted this authority and stopped his agitation.

The problem with this is that there is no such סמ”ג. The סמ”ג does not mention anything about males or females in his section on Gid Hanashe at all.

Worse, due to the fact that the סמ”ג is a sefer that counts and expounds on the 613 Mitzvos, many understood the structure of the סמ”ג to be similar to other Sifrei Hamtizvos (such as the Chinuch) where there is a listing of who the Mitzva applies to. Therefore, it was understood that what R’ Yonasan was actually saying was that since the Mitzva applies to male and female people, it should also apply to male and female animals.

This is a strange logic to say the least. It almost seems that he made a mistake where he fundamentally does not understand the issues.

This was the conclusion of R’ Yechezkel Feivel in his sefer, Toldos Adam[4] that R’ Yonason Eybeshutz just made a mistake and that mistakes just sometimes happen, and he goes on to discuss a number of mistakes that he found in Rabbinic literature.

In his article on this subject, R’ Shnayer Leiman[5] lists a number of Maskilim that used the list of mistakes that are mentioned in Toldos Adam to undermine the authority of the rabbinical leadership, stating surprise how one that studies these texts day and night could possibly make such a grave error, one that a child should be able to spot.

Many other authorities discuss this issue. Some take the approach that an emendation is needed, and that the reference is meant to be to a different sefer with a similar acronym such as Semak[6] or possibly Behag.[7]

Most prominently among these rabbinic authorities, the Chasam Sofer[8] grapples with this issue. He also seems to understand the issue as described, that the סמ”ג does make mention of males and females, however referring to male and female people. He also contemplates the possibility that since the proof that R’ Yonason provided was not correct, maybe we should be careful and not eat the other nerve as well.

Based on this question the Chasam Sofer states that as a general rule men and women are included in any מצות לא תעשה as there is no reason to exclude them, however when there is a reason to exclude women, there would need to be some kind of extra לימוד to include them. Therefore if the nerve is particular to the male animal then that would serve as a reason to exclude women, and there would need to be a לימוד to include them, which we do not have.

I believe that the proper understanding of the Chasam Sofer requires one to look at the source of the reasoning behind why the Gid Hanashe is proscribed in the first place. Yaakov was fighting with the angel of Esav, his brother, and his nerve was displaced due to a blow from that angel. The Torah then states, therefore B’nei Yisroel do not eat the Gid Hanashe (עַל־כֵּ֡ן לֹֽא־יֹאכְל֨וּ בְנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֜ל אֶת־גִּ֣יד הַנָּשֶׁ֗ה אֲשֶׁר֙ עַל־כַּ֣ף הַיָּרֵ֔ךְ עַ֖ד הַיּ֣וֹם הַזֶּ֑ה כִּ֤י נָגַע֙ בְּכַף־יֶ֣רֶךְ יַעֲקֹ֔ב בְּגִ֖יד הַנָּשֶֽׁה). If this nerve was only in males (animals and people), it would make sense that women would be excluded, as the whole reasoning has nothing to do with them.

This logic was disputed by R’ Shlomo Kluger[9] for a couple of reasons. One, he doesn’t believe that the type of logic is appropriate to apply to R’ Yonason, who would have explained his thought process more clearly, and second, the logic of the Chasam Sofer should also apply to Shabbos, for example, as it is a Mitzvas Aseh with a set time, which as a general rule women are excluded from, women should not be included in the negative prohibitions of Shabbos without a limud, based on the principle explained by the Chasam Sofer. Especially as in the prohibition regarding Shabbos it also says “speak to the Bnei Yisroel” why would we not exclude the women?

In 1930 in a publication from Chicago known as Hapardes[10], there was an article written by R’ Shlomo Michoel Neches of Los Angeles. He writes that in his possession (אצלי) he has a first print of the כרתי ופלתי, and R’ Yonasan, the author, emends the סמ”ג to סה”נ and then writes Seder Hilchos Nikkur. It is not entirely clear which Sefer this refers to, as there is no sefer of that exact name.

This answer was picked up by the Pardes Yosef[11], and it appeared to be the final word on the matter. As a matter of clarity, this answer rings true as to what the author’s original intent was, for the following reasons;

-

This “expert” that came to Prague appeared to be satisfied with the answer given to him by R’ Yonason. It is doubtful that someone that went through all that trouble would accept a source that is non-existent, or logic that appears to be dubious.

-

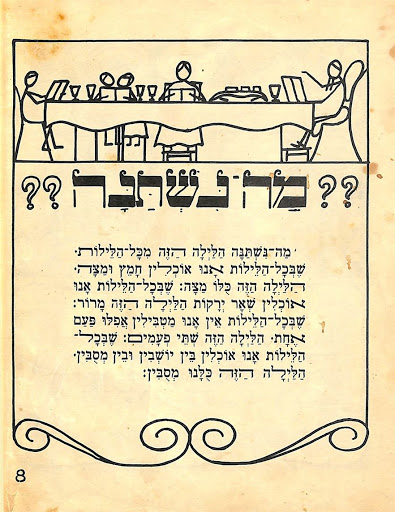

It is clear that R’ Yonasan himself was not the one that prepared the text for printing. It was a student named R’ Ahron Katz[12] .I have in my possession a 1763 Altona edition, and there are many annotations that would point out where there is a good question or a good answer. Here is an example:

It is highly unlikely that R’ Yonasan himself would write in his own sefer “good answer”.

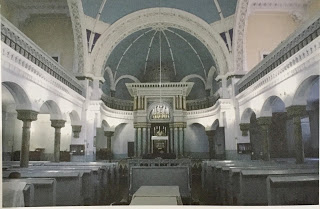

Rabbi Neches was born in Jerusalem and came to Los Angeles in 1910. He was the Rabbi of the famous Breed Street Shul in Boyle Heights (now listed on the national register of historic places) and was the founder of what is now Sharei Tfilah, a shul in the Hancock park area of Los Angeles. He was a collector of seforim and he published articles in Torah journals.

When I moved to Los Angeles it became a mission of mine to track down this volume of the כרתי ופלתי with emendations in R’ Yonasan’s own hand. I spoke with those that had attempted to find this sefer and had been unsuccessful. Apparently Rabbi Neches’s collection was auctioned off after his death and parts of it were donated to the Jewish Federation. No records of this volume were found.

I was able to track down one of the old librarians of the Federation and she told me that most of what they had went to AJU, but she did remember there were boxes of notebooks and other items that were never cataloged. I went to the AJU library and indeed they had boxes that appeared to be never opened. I spent an afternoon going through everything they had, and alas, no כרתי ופלתי.

However, I did find a handwritten catalog of the seforim that Rabbi Neches had in his collection, it was hard to tell if there were more pages due to the degraded condition, however there was no Kreiti Upleiti listed. Not only that but I started to notice that there were no first prints or older seforim on the list. It appeared to be that he was primarily collecting seforim that were printed contemporaneously.

This got me thinking, what if he never had it in his collection? Maybe he saw it in someone else’s collection? There weren’t too many seforim collectors in Los Angeles in the 1920’s but maybe someone had it in his possession as a family heirloom. I decided to look at the academic libraries in California and see if they had a 1763 edition of the Kreiti Uplaiti. With the help of R’ Yaakov Yitzchak Miller, we found it in the Theodore E. Cummings Collection in UCLA[13].

Just as advertised, the Shaar Blat showed the signature of R’ Yonasan Eybushutz, and the emendation was there in siman 65. However, something was wrong. The signature was from R’ Yonasan Halevy Eybeshutz of Leshitz. The author of כרתי ופלתי wasn’t a Levi, nor was he from Leshitz.

This volume wasn’t the personal property of the author of כרתי ופלתי, who fixed an unintentional error, it was the property of an entirely different person, albeit with the same name, that lived 150 years later.

This information, that Rabbi Neches provided was wrong, and therefore the issue of R’ Yonason’s mistake was back in play, was made public a few years back[14], and it would appear that we are back to square one, that this apparent mistake has other potential answers, including that of the Chasam Sofer.

Is it possible that Rabbi Neches simply made a mistake? It did not appear likely to me as it is pretty clear what it says, and he would know that R’ Yonasan, the author, was not a Levi.

Furthermore, in the private collection of Dr. Steven Weiss, there is a sefer, Shaar Yonason written by R’ Yonasan Eybeshutz of Leshits, that was acquired from the collection of Rabbi Neches, and it has the distinctive binding that Rabbi Neches would put on his seforim, so Rabbi Neches clearly knew of that there was another R’ Yonasan Halevi Eybesutz of Leshitz.(See Appendix B)

Rabbi Neches was right.

Rabbi Neches did not make a mistake. Incredibly, this particular volume that was owned by Rabbi Yonasan Halevi Eybeshutz of Leshitz, was also owned by Rabbi Yonason Eybeshutz, the author of כרתי ופלתי.

The odds would appear to be stacked against this, however if you look at the Shaar Blatt of the volume, reproduced here you can see two distinct handwritings, both say “Yonason Eybeshutz”, one appear to be more elongated and cursive and the other more rounded and of an older type, where each letter was not formed in one continuous stream.

Towards the top middle you can see under the first signature reproduced here

And on the left side center you can see a very different autograph, reproduced here

I was able to obtain with the kind assistance of R’ Shnayer Leiman images of signatures that have been verified to be R’ Yonasan Eybeshutz (see Appendix A), and if you put them together, the conclusion is inescapable.

From a receipt for money received that is verified to be R’ Yonason Eybeshutz, the author. (Appendix A)

From the Shaar Blatt of the כרתי ופלתי in UCLA.

This is clear evidence that this volume was the personal copy of the author himself.

Now let’s turn to the emendation, reproduced here

The letters are the rounder letters that are consistent with the author’s writing than the angular writing of the other R’ Yonason Eybeshutz.

It turns out that my thought process in tracking down this volume was actually wrong. The Cummings collection in UCLA was not donated by a local collector, it was actually purchased in 1963 from Israel, from the defunct publishing firm of Bamberger and Wahrman.[15] Mrs. Cummings merely footed the bill for the acquisition in honor of her husband.[16] I corresponded with Arnold Band, who was in charge of the acquisition, and he confirmed that it only made it to Los Angeles in 1963, and he had personal knowledge that the Kreiti Upleiti was part of the acquired collection. As Rabbi Neches moved to Los Angeles in 1910 and his article was published in 1931, he must have been working off of memory or notes that he took from when he saw it in Israel.

The only issue with that is the language Rabbi Neches used in the article, which that it was in his possession (אצלי), which it clearly wasn’t.

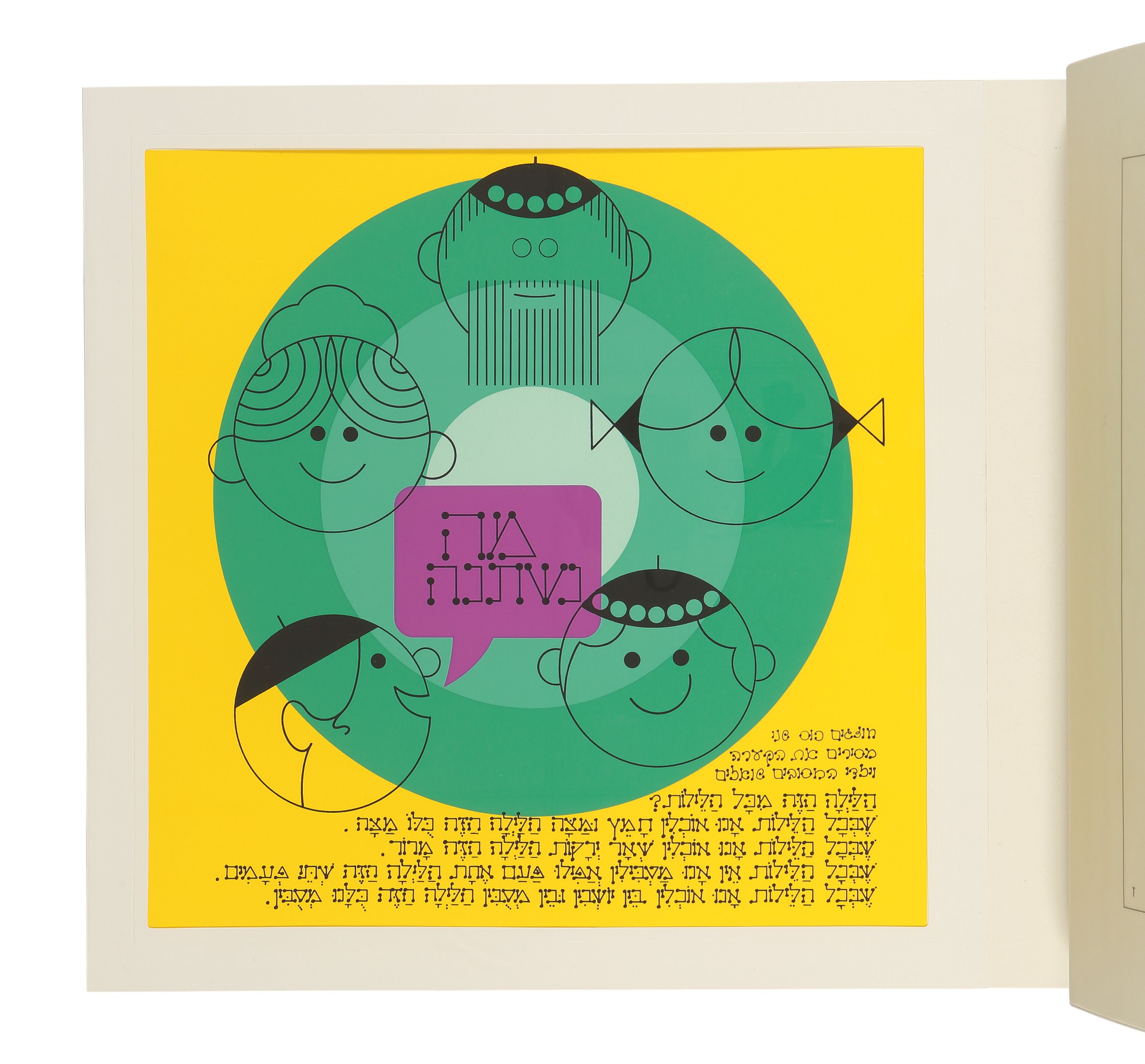

Sefer Hilchos Nikkur

There are a number of candidates for this sefer. Although there are no seforim with this exact title, Leiman[17] makes a persuasive case that the reference is to a 1577 volume printed in Cracow with the title הלכות הניקור , with the section title of סדר הניקור . With the conflation of the two titles, this is probably what R’ Yonason is referring to. The annotations were made by Rabbi Zvi Bochtner, who states that he consulted with Rabbi Moshe Isserles, the Rema, on his conclusions.[18]

This is a sefer that is unusual in that it is highly focused on one area of halacha, annotated by someone that wrote no other sefer and is not a well-known Rav, yet has authority. This sefer would be familiar to those that were in the practical business of porging, however would be unknown to the general learned public. The Rema’s endorsement, of course as the Posek of the German communities would be accepted by the expert as dispositive.

Conclusion

Despite the many twists and turns of this tale, it appears that R’ Yonason Eybeshutz did not make a mistake. The person that prepared the manuscript for printing made an understandable error due to the very unique nature of this particular sefer, and misunderstood which sefer the author was referencing, and subsequently the author himself fixed the issue. Rabbi Neches also did not make a mistake, although some confusion still exists how he actually saw this volume. To use the phrase that Rabbi Neches wrote in his article regarding his discovery of the emendation in R’ Yonason’s own hand, it is a mitzva to publicize this fact.

Appendix A

Appendix B