To Censor or Not to Censor, that is the Question

To Censor or Not to Censor: Electricity on Yom Tov, Illustrations and Other Items of Interest at Legacy Judaica’s March 2020 Auction

By: Eliezer Brodt & Dan Rabinowitz

Legacy Auction’s latest auction will take place on March 26, 2020. Their catalog provides us the opportunity to discuss a few items of interest to bibliophiles.

There are many examples of the phenomenon of censoring or declaring forgeries of teshuvot and other halakhic rulings especially when those rulings are contrary to contemporary practices. Nonetheless, there is at least one example where the urge to suppress contrary halakhic rulings was rejected.[1]

R. Yehiel Mikhel Halevi Epstein of Novogrudok is most well-known for his pseudo commentary on the Shulkhan Orakh, Orakh ha-Shulhan. [2] In addition to that work, he also wrote teshuvot and other important material, some of which was recently reprinted (see our post here) in Kitvei ha-Orukh ha-Shulkhan. One was controversial responsum regarding turning on and off electric lights on Shabbat.

R. Dov Baer Abramowitz was born in 1860 in Lithuania but left at age 10 for Jerusalem. He received ordination from R. Shmuel Salant and in 1894 emigrated to the United States. He held a handful of rabbinic positions, eventually, in 1906 becoming the chief rabbi of St. Louis. Abramowitz sought to reverse the trend of American Jews abandoning the faith and issued a variety of publications that sought to accomplish the goal of strengthening American Orthodoxy. He was involved in the establishment of REITS, the Agudath Harabbonim, and the first branch of Mizrachi in America. [3] In 1903, Abramowitz, as part of his educational program, began issuing his journal, Bet Vaad le-Hakhamim, “the first rabbinic journal in America, to address the waning of religious observance and the lack of unity among religious authorities in America.” [4]. The annual subscription was $2, a fairly substantial sum when the average weekly wage in 1905 was approximately $11. The journal lasted one year with six issues.

The first issue begins with an important announcement regarding the “new technology in the new land” that is a hot water heater and using it on Shabbat. (Bet Va’ad vol. 1, 4). Many important American (in addition to a few international) rabbis participated in the journal. For example, R. Chaim Ozer Gordzinsky’s older cousin and with whom he studied, Zevi Hirsch the rabbi of Omaha, Nebraska, wrote a lengthy responsa regarding riding a bicycle on Shabbat. He argues that the issue is carrying an object on Shabbat in a public space or even in a karmelit, but he identifies no other prohibition. (Bet Va’ad no. 5, Sivan 5663 [1903], 3-7). Thus, it is unclear whether where there is eruv whether he would have permitted riding a bicycle. The journal also includes a letter detailing the revolutionary production process of Manischewitz machine matzot and the various benefits of that process. (Bet Va’ad, vol. 1 25-27). The letter is from the Chief Rabbi of Cincinnati because Manischewitz was originally founded in Cincinnati and only began production in the New York area in 1932 and shuttered its Cincinnati operations in 1958.[5]

The first issue includes four letters discussing the use of electricity on Yom Tov and whether one can turn on and off electrical switches, R. Epstein’s is the first. (Bet Va’ad, vol. 1, 1). Therein he argues that one can turn on electrical switches on Yom Tov. He identifies the issue of nolad or creating something as potentially prohibiting the action but concludes that one is merely connecting the circuits and nothing new is created. But he caveats his responsum with the disclaimer that electricity is uncommon in Novogrudok and his opinion is based upon his best efforts to understand electricity. Indeed, R. Shlomo Zalman Aurbach refers to R. Epstein’s responsum as containing “devarim tmuhim” and explained that they are a product of a faulty understanding of the technology.(Shlomo Zalman Aurbach, Me’orei Or (Jerusalem, 1980), appendix). Lot 85, includes this volume as well as the second issue.

R. Epstein was not alone in permitting electricity on Yom Tov, indeed, the other three letters in Bet Vaad similarly permit electricity. Other contemporary rabbis also rule in favor of electricity.

Nonetheless, those are minority views and today the common Orthodox practice is to refrain from turning on and off electrical switches. When the publishers of R. Epstein’s writings were deciding what to include in Kol Kitvei, they approached R. Chaim Kanievsky and asked whether they should exclude R. Epstein’s responsum regarding electricity. Presumably, they were concerned that one of the greatest halkhic authorities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries permitted what is “established” law to the contrary (despite the other opinions). But R. Kanievsky rejected that position and held that the responsum should be reprinted.[6]

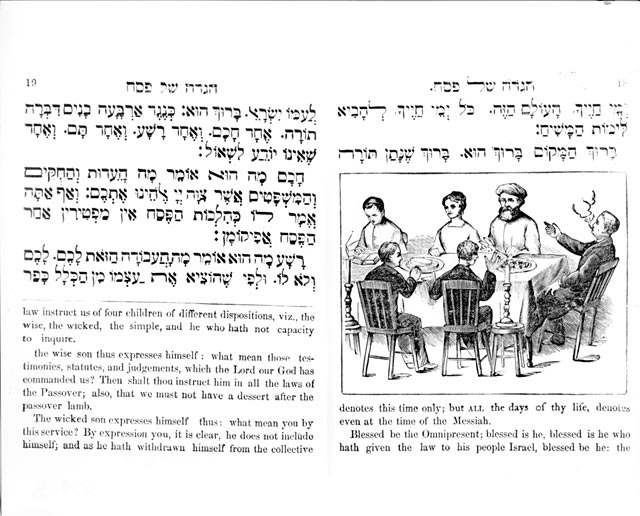

Another example of Americana and the use of fire on Yom Tov appears in one of the first haggadot printed in the United States. The 1886 illustrated Haggadah contains a depiction of the four sons. Depicting the four sons is very common in the illustrated manuscripts and printed haggadot. In this instance, the wicked son’s disdain for the seder proceedings shows him leaning back on his chair and smoking a cigarette. According to many halakhic authorities, smoking is permitted on Yom Tov, nonetheless, the illustration demonstrates that at least in the late 19th-century smoking was not an acceptable practice in formal settings. (For a discussion of smoking on Yom Tov, see R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin, Mo’adim be-Halakha (Jerusalem: Mechon Talmud Hayisraeli, 1983), 7-8).

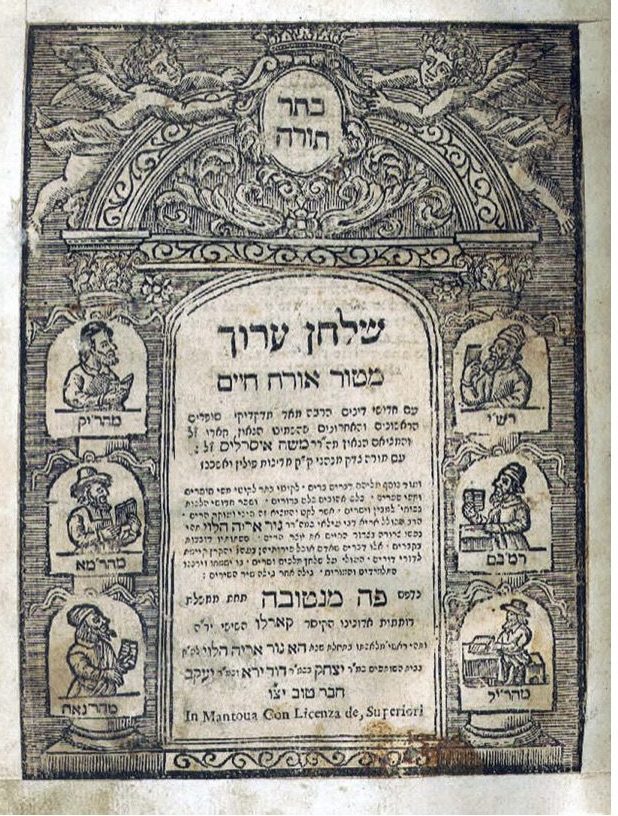

One of the other lots that also implicates illustration is lot 94, Shulhan Orakh im Pirush Gur Areyeh, Mantua, 1722, that contains the commentary of R. Yosef ben Ephraim Gur Areyeh Halevi. As we have previously discussed at the end of this post, the Gur Areyeh’s title page to the first volume depicts six relevant personalities, Rashi, Rambam, MahaRIL, R Yosef Karo, R. Moshe Isserles, and R. Gur Areyeh. According to some accounts, this illustration roused the ire of some rabbis because they felt the depictions were crude, and in some instances seem to show at least one rabbi in violation of Jewish law. Allegedly, they claim that the Rambam is shown with insufficient peyot (sidelocks) in addition to long hair (as do others). Thus in the remaining volumes of this edition, the illustrations were removed and they no longer appear (although at least in one preserved copy the illustration is repeated in the Yoreh De’ah volume).

One lot, # 161, is an incredible discovery: R. Yosef Dov Halevi Soloveitchik’s (Bet Halevi) copy of the Halakhot Gedolot (BeHaG). This copy contains hundreds of unpublished glosses, citations, and cross-references. This copy establishes that the Netziv was not the only Rosh Yeshivah of Volozhin who was involved in the works of the Geonim. One only can hope that whoever purchases this copy will publish the notes.

Another such item is # 87 is a presentation copy of Derishat Tzion that contains the commentary of R’ Tzvi Pesach Frank. Although not noted in the description R. Frank presented this copy to R’ Chaim Hirschenson. In his Shut Malkei Bakodesh,(4:10) R’ Hirschsenson prints a very interesting letter from R Frank after he received a copy of one of R. Hirschenshon’s book. R Frank took issue with some of R. Hirschenshon’s conclusions and to his credit, he prints it without censoring it. The book being auctioned might have been a gift from R Frank in return for the gift he received. R. Frank’s letter is full of fascinating contemporary descriptions of Jerusalem.

Finally, for a discussion regarding lot 93, Menukha ve-Kedusha and censorship see our post here.

Finally, for a discussion regarding lot 93, Menukha ve-Kedusha and censorship see our post here.

[1] See, for example, Yakkov Shmuel Speigel, Amudim be-Tolodot Sefer ha-Ivri: Ketivah veha-Atakah (Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press, 2005), 241-97; Marc Shapiro, Changing the Immutable: How Orthodox Judaism Rewrites History (Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2015), 81-118.

[2] For a biography see R. Eitam Henkin, Tarokh le-fani Shulkhan (Jerusalem: Maggid, 2019). Regarding this book see our discussion here.

[3] Yosef Goldman, Hebrew Printing in America 1735-1926: A History and Annotated Bibliography (Brooklyn: [YG Books], 2006), vol. 1, no. 584, 514. See our reviews of Goldman’s bibliography here and here.

[4] Goldman, Hebrew Printing, no. 591, vol. 1, 521.

[5] See generally, Yossi Goldman, vol. 1, no. 591, 520-21. Bet Vaad contains materials beyond responsa and halakhic discussions, including poetry, discussions regarding Jewish life in America such as yeshivot, restaurants, and a fable written in verse.

For a discussion of Manischewitz, see Jonathan D. Sarna, “How Matzah Became Square: Manischewitz and the Development of Machine-Made Matzah in the United States,” in Rebecca Kobrin, ed., Chosen Capital: The Jewish Encounter with American Capitalism (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2012), 272-288; Jonathan D. Sarna, How Matzah Became Square: Manischewitz and the Development of Machine-Made Matzah in the United States (New York: Touro College, 2005).

[6] Regarding the position that seeks to portray Orthodox Judaism a monolithic halakhic process and view as legitimate only certain opinions see Adiel Schremer, Ma’ase Rav: Shekul ha-Da’at ha-Halakhati ve-Eytsuv ha-Zehut ha-Yahadut (Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press, 2019), 191-97.