Review of Mada Toratekha: Studying Gemara in Broad-based Depth

Review of Mada Toratekha Rav Yehuda Zoldan: Studying Gemara in Broad-based Depth

ר’ יהודה ברנדס מדע תורתך מסכת ברכות, מכללת הרצוג, אלון שבות תשעט

The Following post is a short review on a new work from Rabbi Professor Yehuda Brandes on Berakhot.

For another recent article of Rabbi Brandes about Learning Gemara see this issue of Hakirah.

For a sample chapter of this new work or to purchase this work email Eliezerbrodt@gmail.com

Over the years, a variety of different styles and approaches have been developed and applied by people who devote themselves to the study of Gemara in a serious manner. Popular genres include: iyun, pilpul, emphasis on the halakhic outcome, ethical and value-based insights, academic studies, linguistic content and literary structures, historical aspects and Talmudic realia, among others. Few individuals can successfully apply all – or even most – of the styles in their own learning, as it would require the ability to understand and master different approaches and “languages” of learning.

Most people who sit down to learn and teach Gemara look at each issue on its own, using the approach with which they are most comfortable. They comment and suggest novel approaches on one specific matter or another, noting an interesting ruling of Maimonides or of one of the other commentaries on the issue, and so forth. In the commentaries of the aharonim (later commentaries), even after analyzing a topic in the Gemara and delving into its many details, we almost never find the presentation of a broad perspective containing insights that reflect on our place in the contemporary world.

Rabbi Professor Yehuda Brandes, who serves today as head of Herzog College in Alon Shvut, is one of the few individuals who is conversant in the almost all of the abovementioned areas. He has succeeded in weaving all of this together in an impressive whole in his newly published book Mada Toratekha on Tractate Berakhot, the tractate that is currently being studied in the new daf yomi cycle. His yeshiva background – at Yeshivat Netiv Meir and Yeshivat HaKotel – the academic track in the Talmud that he has pursued, his rich experience as a high school teacher and lecturer in academic settings and in his community, his experience with different types of learners of different ages, his personal skills including an impressive ability to analyze different “languages” in depth, and the broad perspective that he offers, create a new and unique mix that is manifest in the book. [A previous book in this series, on Tractate Ketubot, was published in 2007.]

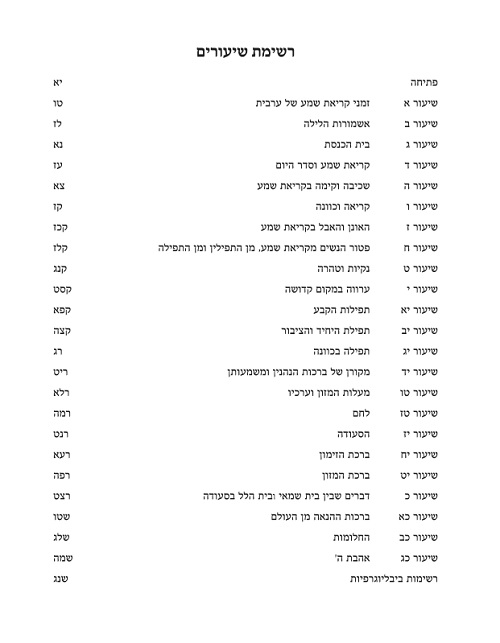

There are 23 presentations in the book, each of which deals with topics appearing in Tractate Berakhot. Each one of the presentations contains material from the Jerusalem Talmud and from Midrash Halakha, together with the approaches of rishonim and aharonim (early and later commentaries), classic Yeshiva-style exegesis, references in footnotes to academic research, together with Hassidic and theological works that relate to the topic under discussion. All of this is presented succinctly, with grace and sensitivity, using modern language. The writing is both challenging and thought provoking.

One place where this broad sweep can be seen is in the list of books and articles that appears in the bibliographic section at the end of the book – something that you rarely find in traditional commentaries. Under “alef,” for example, we find Rabbi Moshe Alashkar, Professor Hanoch Albeck, Rabbi Yosef Shalom Eliashiv, Professor Yaakov Nahum Epstein, Rabbi Yechiel Michel Epstein, and more – unusual neighbors to find sharing space on a bookshelf. This work represents a unique composite of different worlds.

Structural analysis and existential insights

Here is an example of one of the presentations in the book: “Praying with intent” (Chapter 13). The presentation opens with the well-known Mishnah that appears at the beginning of the fifth chapter:

One may only stand and begin to pray from an approach of gravity and submission (koved rosh). There is a tradition that the early generations of pious men would wait one hour, in order to reach the solemn frame of mind appropriate for prayer, and then pray, so that they would focus their hearts toward their Father in Heaven. Standing in prayer is standing before God and, as such, even if the king greets him, he should not respond to him; and even if a snake is wrapped on his heel, he should not interrupt his prayer.

(b. Berakhot 30b)

Rav Brandes gets right to the point, noting that the Mishnah contains three distinct messages:

– One must pray from an approach of gravity and submission (koved rosh);

– Serious preparation for prayer is an indication of piety;

– It is forbidden to interrupt one’s prayers. This is emphasized by the Mishnah by presenting extreme situations, e.g., when greeted by a king or challenged by a snake.

These three messages touch on different points. Submissive prayer describes the behavior and mental state of the worshiper. Preparation and focus in prayer concentrates on the content, the interpretations of the words, and the very consciousness of standing before God. The prohibition against interrupting one’s prayers is a practical issue emphasizing the need to maintain continuity in prayer even in the face of imminent danger.

From here Rabbi Brandes moves to the Gemara’s discussion, analyzing the four Amoraitic opinions offered, interpreting the concept of koved rosh. Although only one opinion will be accepted as law, Rabbi Brandes examines each of the four opinions – and the verses that they quote – deriving how we are to approach prayer, how we can connect awe and fear, joy and trembling. From here we are treated to a close reading of the baraitot that are brought by the Gemara that parallel the structure of the Mishnah:

One may neither stand to pray from an atmosphere of sorrow nor from an atmosphere of laziness, nor from an atmosphere of laughter, nor from an atmosphere of conversation, nor from an atmosphere of frivolity, nor from an atmosphere of purposeless matters. Rather, one should approach prayer from an atmosphere imbued with the joy of a mitzva.

We continue with the flow of the Gemara, as the author deals with such issues as how we can focus our hearts towards heaven in prayer, or how to train ourselves in “the art of restraint” by emulating Rabbi Akiva who prayed privately in an enthusiastic manner, in contrast with his restrained prayer when praying in public.

In the context of prayer, the Gemara brings a number of aggadic statements about Hannah, the prophet Shmuel’s mother, whose prayer (see 1 Sam. Chapter 2) serves as an archetype for Jewish prayer generally. These statements are analyzed and recorded under a series of headings, like: “Midrash Hannah – Characteristics of an eminent worshiper,” “Intoxicated prayer,” “The expanse of the worshiper.”

Having gathered the many sources appearing in the Gemara together with those that he introduced in his presentations, Rabbi Brandes sums them up with insights that are practical, yet existential, and applicable to the here and now. He writes: “Every individual, whether young or old, has his or her role in prayer. The Talmudic discussions, both halakhah and aggadah, can serve as a guide and a compass, directing us towards the study and experience needed for meaningful prayer. Still, the unique characteristics and personal meaning of prayer can only be attained through the efforts of the individual and the community in every generation. They must shape their experiences according to their own image and principles, based on the guidance of the prophets of Israel, its sages and its founders” (p. 217). In concluding his lesson on birkat hamazon (the Grace After Meals), Rabbi Brandes writes: “When reading the Shema and its blessings, the worshipper accepts the Yoke of Heaven ‘when you sit at home and when you travel on the way,’ with eyes closed and focused intent, disengaged from the surrounding environment. When going to pray in the synagogue, one stands before God in the midst of one’s community. It is at the dinner table at home when we have the opportunity to bring Godliness into the very heart of the physical world. This is the responsibility of the Jewish people living in God’s land, enjoying the sweetness of its fruit and enjoying God’s presence (p. 243).

The lessons on other topics that appear in this book are treated in a similar fashion. These include, for example: “Times of the evening recitation of the Shema,” “Women’s exemptions from the commandments of Shema, Tefillin and prayer,” “Sources of blessings and their significance,” “Bread,” “Points of difference between Bet Shammai and Bet Hillel in regard to a meal,” “Dreams,” and more.

Calling for a New Approach

The format of the book is also unusual. There are two columns on each page, with a different font for the sources quoted from the Talmudic works and the commentaries, and with rich footnotes for reference. The book is written in a literary Hebrew and is well edited. This design is reminiscent of the layout in traditional commentaries on the Talmud, which often appear in two columns, albeit usually in “Rashi script,” with no subheadings, no footnotes, no language editing and many abbreviations. One can assume that the choice of this format is meant to suggest that what is found in this book is “new wine in a venerable container.”

In his introduction to the book, Rabbi Brandes notes the context in which these lectures were presented over the years: in the Himmelfarb school in Jerusalem, in Beit Morasha and in community lectures. Each group contributed their part, and the unique structure of these lessons drew from their participation. The variety of students and their different ages reinforces the argument that a high quality and challenging Gemara class speaks to everyone. The tempo may be different, the emphasis might change – there are bound to be other differences, as well – but if a broad and in-depth presentation is offered, everyone becomes a partner in thinking and suggesting solutions. The outcome will be fresh insights and understandings with no limitations based on age or place.

Many of the Talmudic tractates – and Berakhot is among them – have a myriad of recent commentaries on them that have been published. To that list of books on Tractate Berakhot we now have a new – and unique – addition. This work offers a new approach that can speak to contemporary students. We are a generation that collects everything that has been written throughout the ages. The challenge taken up by Rabbi Brandes is to gather all those styles of learning in a respectful and harmonious fashion, and to use them to build additional layers, in a manner that both inspires and challenges.