Concerning Athei Merahiq, Nasog Ahor, and the Ravia Mugrash, and More

Concerning Athei Merahiq, Nasog Ahor, and the Ravia Mugrash, and More

by Rabbi Avi Grossman

(The author would like to express his gratitude to those who supported the recent publication of his Haggadat Hapesah. Contact him at avrohom.grossman@gmail.com to obtain a copy. Parts of this post originally appeared here.)

Recently, I was privileged to be part of a fun-yet-esoteric discussion on matters of Hebrew grammar. First, some background: there is a grammatical phenomenon in Biblical Hebrew known as “nasog ahor,” literally, “stepped back.” In certain words that are accented on the last syllable but have an earlier syllable that is open, sometimes the accent is shifted to that earlier syllable if the proceeding, grammatically connected word is accented on one of its earlier syllables. Examples with which many are familiar include the blessing on the Torah, wherein the word בחר, when connected to the next word, BA-nu, becomes “a-sher BA-har BA-nu,” or the blessing on the bread, wherein the word would normally be ham-mo-TZI, but when connected to LE-hem, it becomes ham-MO-tzi LE-hem.

The second is a phenomenon that is often a consequence of the first, and it is not well known at all. “Athei merahiq,” lit. “coming from afar,” is when a word ends with an open, unaccented syllable vowelized with a qamatz or segol and is joined to the proceeding word that is accented on the first syllable, placing a dagesh in the first letter of that latter word. The fact that the first word’s last syllable is unaccented may be due to the “stepped back” phenomenon described above, but not always. Examples that come to mind from recent Torah readings include Genesis 30:33, w’A-n’tha BI, in which the beth has a dagesh, and 31:12, O-seh LACH, in which the lamed has a dagesh.

While the nasog ahor phenomenon makes sense to me, and interestingly enough, has its parallels in spoken English, for instance, I do not understand the latter phenomenon, nor am I aware of any explanation among the various authorities. However, based on the theories I outline in my book, I can tolerate why this phenomenon of basically closing the final syllable of the first word would happen only with the segol or qamatz. The segol is a t’nu’a q’tana, a minor or short vowel, and the only t’nu’a q’tana that occurs in open, accented syllables that end words, making it more versatile than the patah, the only other short vowel that occurs in open or accented syllables, and because it does not have a natural semivowel at its end (the Y sound at the end of the long E and A sounds, or the W at the end of long O or U sounds), closing its syllable does not result in an unaccented consonant cluster, which, as explicated by Gesenius, is not allowed. As for the qamatz, it is the only t’nu’a g’dola, major or long vowel, that does not have a natural semivowel conclusion, and once again closing its syllable does not result in the formation of a consonant cluster, although this would then require us to explain why an ordinary qamatz is treated like the other major vowels if it is lacking this essential feature.

Like every rule, athei merahiq has its exceptions. For example, we read A-sa LO in Genesis 37:3 , and in that case, the lamed should have a dagesh, but it does not, or in 1:5, QA-ra LAY-la, and once again the lamed should have a dagesh, but it does not. It seems that whenever a past tense, singular, masculine verb in the pa’al conjugation that ends with a silent hei or alef is accented on its first syllable, it does not place a dagesh at the beginning of the next word. I have not yet found an explanation as to why this class of verbs should not follow the athei merahiq rule, and it is quite surprising being that their female counterparts (words like קראה and עשתה, etc.) are sometimes accented on their first syllables and then follow the rule of athei merahiq.

Recently, Dr. Marc Shapiro, k’darko baqodesh and blogs, released another must-read article on the Seforim blog. In it he made the following point:

In the ArtScroll siddur, p. 86 it reads:

ועל מאורי אור שעשית, יפארוך, סלה

There is a dagesh in the ס of סלה. This means that the comma after יפארוך is a mistake, as you cannot place a dagesh in this ס if preceded by a comma.

Dr. Shapiro’s assumptions in this matter are that the samech of sela receives a dagesh because of the athei merahiq rule, meaning that the previous word, y’fa-a-RU-cha, must be connected to it, and therefore it would be wrong to have a comma between the words. If there were a comma, then the samech would not receive a dagesh. It is then that I took issue with his argument, and wrote the following to him:

Actually you can have a dagesh. For example, אַ֭שְׁרֵי יֽוֹשְׁבֵ֣י בֵיתֶ֑ךָ ע֝֗וֹד יְֽהַלְל֥וּךָ סֶּֽלָה.

This is a well-known verse from the Psalms.

Now, you might be initially inclined to dismiss this example, as in this case, sela is connected to the previous word by the trop, but the truth is that in the Sifrei Emeth, what would normally be a mercha tip’ha (pause) siluq succession (in the other 24 books), does not and cannot exist when the word with the siluq is less than three whole syllables (or when accented before the last syllable, four whole syllables). Instead, what would be the tip’ha, the mafsiq, becomes the m’shareth of the siluq. For example, in Chronicles we have this well-known verse

הוֹד֤וּ לַֽיהוָה֙ כִּ֣י ט֔וֹב כִּ֥י לְעוֹלָ֖ם חַסְדּֽוֹ׃

But in the Psalms, because the word hasdo only has two syllables, the last three words are all connected, and hasdo is connected to the previous word:

:הוֹד֣וּ לַֽיהוָ֣ה כִּי־ט֑וֹב כִּ֖י לְעוֹלָ֣ם חַסְדּֽוֹ

The trop of the word ki is not the tip’ha-mafsiq that exists in the other books, rather, it is also a m’shareth:

This happens to also hold true for the etnah in Sifrei Emeth, which, according to R’ Breuer, and as you can see from this example, has the weight of a zaqef of the other books, and also converts its mafsiq mishneh into a m’shareth when the word with the etnah is “short.” I have yet to figure out why this is. So, for example, if the verse lha’alot ner (mafsik) tamid were to be in Psalms, it would just be lha’alot ner tamid. Or the verse nagila w’nism’ha vo. In the Torah, it would have been nagila w’nism’ha (pause) Bo, but because bo is a short word, it is automatically connected to the previous. Every time the word sela appears at the end of a verse, it must be connected to the previous word, even if in context, the mafsiq that was supposed to be right before it would indicate the highest grammatical disjunction. For example, in the above verse, if sela were not there, it would be read “ashrei (pause) yosh’vei veithecha; od, y’hal’lucha (full stop).” And the same is true for basically every verse in Psalms that ends with sela.

:יְהוָ֣ה צְבָא֣וֹת עִמָּ֑נוּ מִשְׂגָּֽב־לָ֨נוּ אֱלֹהֵ֖י יַֽעֲקֹ֣ב סֶֽלָה

Logically, according to our accepted use of commas, all of those verses should have a comma, or perhaps even a period, right after the penultimate word. “The Lord of Hosts is with us; Our stronghold is the God of Jacob. Sela!” Yet, here sela is once again connected to the previous word.

So yes, if “m’orei or she’asita, y’faarucha, sela” were a verse in Psalms, the last two words would be connected (because y’fa’arucha is accented on an early syllable and ends with a qamatz) and the samech would have a dagesh.

Dr. Shapiro had some follow up questions:

I see that you are assuming that a tipcha equals a comma (and let’s assume we are dealing with Tehillim). Leaving aside the issue of since when do siddurim insert commas before words like they did before סלה? I have not seen that anywhere. But is a tipcha really a comma?

He also complimented me, and I wrote the following response to him:

The answer is that tip’ha is sometimes a comma. The rule in the 21 ordinary books of scripture is that tip’ha is the mafsiq before the siluq. Every verse in those books has at the very least a siluq and a tip’ha.

This needs to be clarified. There are probably only a few dozen or so verses wherein the last mafsiq before the siluq is an ethnah, but in those cases, the ethnah is preceded by a tip’ha.

However, the objective value of the tip’ha depends on the entire context of the particular verse. In a short verse, like “Adam Sheth Enosh” (I Chronicles 1:1) it corresponds to absolutely no punctuation. In וַיָּ֥זֶד יַֽעֲקֹ֖ב נָזִ֑יד וַיָּבֹ֥א עֵשָׂ֛ו מִן־הַשָּׂדֶ֖ה וְה֥וּא עָיֵֽף׃, the second tip’ha has the value of what we would call a comma, while the first tip’ha (under Yaakov) [does not.] If the word sela would ever end any verse in the 21 books, it would be preceded by a tip’ha, by definition, or perhaps the even stronger ethnah, and then you would have to examine the verse’s context and meaning to determine what ever mafsiqim are featured. As you know, in some verses, there aren’t even zaqefim, let alone etnahim, before the tip’ha, e.g. וְהָי֞וּ הַדְּבָרִ֣ים הָאֵ֗לֶּה אֲשֶׁ֨ר אָֽנֹכִ֧י מְצַוְּךָ֛ הַיּ֖וֹם עַל־לְבָבֶֽךָ׃

In contrast, the verses in Sifrei Emeth have almost half a dozen ways of ending! Some have a ravia mugrash where the tip’ha would be, some turn the final ravia into a m’shareth (like the examples I showed you earlier), and some have a string of m’shar’thim with no mafsiqim, once again due to the shortness of all the words: עֵֽינֵי־כֹ֭ל אֵלֶ֣יךָ יְשַׂבֵּ֑רוּ וְאַתָּ֤ה נֽוֹתֵן־לָהֶ֖ם אֶת־אָכְלָ֣ם בְּעִתּֽוֹ׃

My guess is that this has something to do with certain musical rules.

The sages noted that the verses of Sifrei Emeth tend to be shorter than the verses in the rest of the Bible. I would also add that after careful analysis, including a thorough comparison of the verses and passages that appear in both (David’s victory song, for example), the verses of Emeth tend to have less mafsiqim. I would really like to find someone with whom to work to understand these phenomena, but alas, I immigrated to Israel after R’ Breuer and R’ Kappah left us.

Therefore, in answer to your question, I insert the comma because that is how the verse is to be understood when translated, and that is how the English language and modern Hebrew work, but in the scriptural form, the laws of grammar/music dictate that the pause be subsumed due to the shortness of the word. My belief is that the siddur makers should always leave in the trop where ever possible, but certain liturgies are not biblical, and therefore the siddur makers try to help the reader by adding our Western conventions.

(75:4 is also a perfect example, by the way: נְֽמֹגִ֗ים אֶ֥רֶץ וְכׇל־יֹשְׁבֶ֑יהָ

אָנֹכִ֨י תִכַּ֖נְתִּי עַמּוּדֶ֣יהָ סֶּֽלָה

If we were to parse this verse using modern commas and periods, the period would be before the word sela. And that is how, for example, the JPS 1917 has it.)

Consider: How should one say “al tig’u bimshihai“? In Chronicles, there is a disjunctive pashta on the first word, leaving the dagesh in the following beth, but in the Psalms, tig’u has a conjunctive mercha, making the next word “vimshihai.” Or “Lo tirtsah, lo tinaf.” When read with one set of trop, the tavim are strong, while when read with the other set, the tavim are weak. When you are speaking or lecturing, or perhaps reciting those verses as part of your prayers but not as part of whole paragraphs, which set of trop do you use? I have no answer at the moment. But this doubt must exist when the liturgy adds sela to the end of a sentence. Do we read it as though it were one of the Psalms?

In the three books of Emeth, there are many verses that conclude with a series of connected words, whereas in the other books, such a series would demand a number of mafsiqim preceding the end of the verse. However, with regards to the beginnings of verses, the opposite is true, when we deal with unusually long words. In the books of Emeth, the tendency is to have more mafsiqim, whereas in the other books, there are sequences of many connected words, usually leading into the flourishing mafsiqim of the fourth level, pazer, t’lisha, gershayim, etc. This might have something to do with those flourishes. Because the books of Emeth are more musical, the flourishes tend to be at the ends, so that would allow for more conjunctives, whereas in the other books, the flourishes and conjunctives are concentrated at the beginnings of verses.

…

There is much to be said about the ravia mugrash (the trop that marks words such this: נַ֝פְשִׁ֗י,) one of the most common disjunctives found before the conclusion of verses in the books of Emeth. Most often, it does fill the role of the tip’ha found before the conclusion of the vast majority of verses in the rest of the Bible, but not always.

The zaqef gadol that occurs on “long” words that, due to their lack of an open syllable that is not accentable, can not receive a secondary accent (ta’am mishneh) is represented by the ordinary symbol for the zaqef qaton and another symbol, called a m’thiga, the symbol that normally represents the qadma or pashta, placed above the second letter of the word. Together, these two symbols signify the zaqef gadol, and not, as many believe, that the word is actually hosting both the accent of the zaqef and the secondary accent of the pashta/qadma. An illustration: לְזַ֨רְעֲךָ֔. In this case, all of the accents and musical notes should be placed on the final syllable, and no accent whatsoever is put on the first syllable, zar, the one under the m’thiga. Many are misled by the m’thiga, and it is unfortunate.

The ravia mugrash is similar to this type of zaqef gadol in that it is represented by the combination of two symbols, in this case the common ravia above the accented syllable plus another symbol, the one that normally represents the geresh, above the first letter of the word. Once again, these two symbols combine to form one unified symbol, and the presence of the geresh symbol on the first letter does not indicate secondary accentage. However, there are a number of cases in which a single word does have multiple trops, and the lesser of the two does indicate a secondary accent, for example, in words that have a munah and a zaqef qaton, or both qadma and azla (geresh), or, in rare cases, a tip’ha and an ethnah (Numbers 28:26) or the like on exceptionally long words.

The ravia mugrash most often appears toward the end of a verse when what follows is a “long” word, or at least two words. Generally speaking, a “long” word is one that has three full syllables, whereas two words will do the trick even if combined they only have two full syllables. When discussing post-talmudic Hebrew poetry, the terms t’nu’a (lit., a “movement”) and yathed (lit., a “peg”) are used to describe the two types of syllables that can be formed in Hebrew. The former refers to a pure syllable, whether closed by a consonantal sound or not, while the latter refers to a pure syllable preceded by the sound of a consonant marked with a sh’wa na‘* (or a guttural letter vowelized with some sort of hataf vowel, which are types of sh’wa na’.). For the purposes of Emeth, both t’nu’oth and y’thedoth are (often literally) counted as syllables, whereas in the other books of the Bible, there are cases in which this categorical lumping is not admitted. (In later Hebrew terminology, including modern Hebrew, t’nu’a is also the word for a vowel sound, with the connection being that every syllable has but one vowel sound, with options for consonantal sounds to both precede and follow the vowel.) Rabbi Meir Mazuz uses this piyut as an example for beginners:

adon (yathed, as the alef is vowelized with a hataf patah) ‘o-lam (two t’nu’oth, pure syllables) asher (yathed) ma-lach (two t’nu’oth)…

These definitions of syllables are entirely unlike the ones with which we are familiar from our spoken languages. Indeed, we must also keep in mind that throughout the Bible, words connected by maqqafim (hyphen-like symbols) are, for all of our grammatical intents and purposes, considered as one word. Whether a compound noun, adjective, or adverb is “hyphenated” into one compound word or not is a delicate syntactical matter, and sometimes both forms appear in a single verse.

In a particular verse, if there is only one word (according to our liberal definition) after the word that can potentially receive the ravia mugrash, in order for the ravia mugrash to appear, that ultimate word must, as we have said, have at least three syllables. Therefore, the following are not considered syllables:

- Any syllable that may be after the accented syllable. That is, in words accented mil’eil, before the last syllable, the latter syllables do not count. Thus, words like KE-sef and ME-lech are considered monosyllabic for our purposes, while huq-QE-cha, and yag-GI-du are merely disyllabic.

- Similarly, the patah g’nuva necessitated by the combination of long vowels closed with final guttural consonants also does not count as a syllable: ya-REI-ah and ma-NO-a’ only have two syllables for our purposes, while Noah is a monosyllabic name.

- Any letter vowelized with a sh’wa na’ or hataf vowel also does not form a countable syllable. Therefore, words like l’o-LAM only have two syllables. In poetry terms, both y’thedoth and t’nu’oth count as only one syllable each.

- When a prefix waw with a sh’wa is converted to a shuruq because it precedes a labial letter, and therefore seemingly forms a third syllable, it still does not count, and it is viewed as though it remained a waw with a sh’wa na’. Examples: u-va-A-retz (Psalms 113:6) and u-vi-NA (Proverbs 23:23) are both still considered as disyllabic, the former because the last syllable is after the accented syllable. (When the prefix waw becomes a shuruq because the first letter of the word is vowelized with a sh’wa, in most cases a new, countable syllable is formed with the original first letter, e.g., וּשְמוֹ ush-MO or וּבְיוֹם uv-YOM, and in some exceptional cases recorded in the masora, the waw/shuruq forms its own syllable, and the subsequent sh’wa is na’ is still connected to the next syllable, e.g., u-Z’HAV (Genesis 2:12). In either of these cases, a syllable is added to the count.)

- Lastly, if a word has every type of additional factor that does not increase its syllable count, i.e., both of its true syllables are preceded by some form of sh’wa na’ or hataf and it has another, third syllable after the accented syllable, then it may be considered a long word, e.g., l’sho-L’HE-cha (Proverbs 22:21), y’va-R’CHU-cha (Psalms 145:10) , and y’sha-R’THEI-ni (Psalms 101:6), but as can be seen from Psalms 145:6, asap-P’REN-na, this is not always the case.

Thus, in Proverbs 29:22, the hyphenated word rav-PA-sha is not considered two words because of the maqqaf, nor is it considered a “long word” because it only has “two syllables,” the third syllable not being considered because it proceeds the accent, and therefore the preceding word is marked with a conjunctive munah, and the same can be said about the word y’shar-DA-rech five verses later, while in Psalms 145:4 EIN HE-qer does allow for a preceding ravia mugrash despite its lack of syllables because the words remain unhyphenated.

The d’hi, (as in: ר֭וּחוֹ ) which we have addressed earlier, is also slightly misleading, due to its resemblance to both the disjunctive tip’ha of the rest of the Bible and the connective tip’ha of Emeth, and the fact that it is always written before the word, thus never indicating which syllable is to be accented. Further, the rules we have stated above regarding the ravia mugrash before the silluq apply to the d’hi that appears before the ethnah, i.e., that it is replaced by a connective trop in certain circumstances, but with one important addition: If no other word appears in the ethnah‘s domain before the word that is to receive the d’hi, and no other words are to appear connected to the word with the ethnah after the d’hi, the d’hi is replaced by a mercha, its counterpart conjunctive. This explains the phenomenon in the example I brought earlier, in the following verse with which many are familiar (I Chronicles 16:22):

אל־תִּגְּעוּ֙ בִּמְשִׁיחָ֔י וּבִנְבִיאַ֖י אַל־תָּרֵֽעוּ׃

The second word is bim-shi-HAI, with a strong beth sound, whereas in the corresponding verse in Psalms(105:15),

אל־תִּגְּע֥וּ בִמְשִׁיחָ֑י וְ֝לִנְבִיאַ֗י אַל־תָּרֵֽעוּ׃

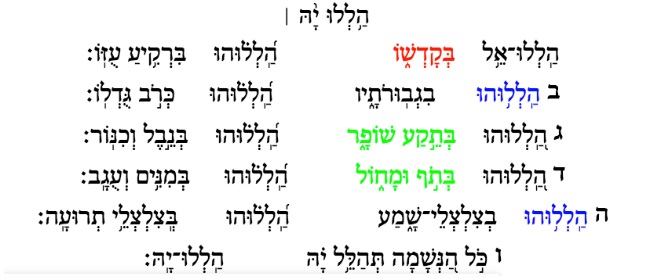

the word is vim-shi-HAI, with a weak, veth sound. The (compound) word al-tig-G’U before the (long) word vim-shi-HAI has no other words before it, and therefore it is not marked with the disjunctive d’hi. This also explains the following noticeable break in the pattern in the final psalm, which is a good illustration of most of the rules we have discussed until this point:

As you can see, the word hal’luhu, is usually marked with a disjunctive, because it is a verb followed by an object composed of multiple words (as in the conclusions of these verses), but in the second and fifth verses, the first hal’luhu‘s (in blue) have no words before them, nor do the subsequent words with the ethnah’s have other conjoined words. Thus, the hal’luhu‘s in those verses lose their disjunctive d’hi’s, and the following words (or hyphenated compound word), are modified, vig-vu-ro-THAW or v’tzil-tz’lei-SHA-ma’, respectively, and the prefix beth in each word is weak. In verses 3 and 4, the word hal’luhu in the first halves is proceeded by multiple words in the domain of the ethnah (the green words), and therefore it keeps its disjunctive d’hi. Now, one may ask, why is it that in verse 5 b’tziltzlei shama’ becomes one hyphenated word, whereas in verse 3, the seemingly shorter words b’theqa shofar remain separate? The answer lies in the fact, that, based on what we wrote above, b’tziltz’lei and b’theqa are both “short” words, but b’theqa has an open syllable capable of receiving an accent, whereas b’tziltz’lei does not have an accentable syllable that would not be adjacent to the accented syllable of SHA-ma’. Its latter syllable is obviously unfit due to proximity, and its first syllable is closed, making it also ineligible. Secondary accents may only be placed on open syllables.

…

A major exception to these rules occurs a number of times in the shortest verses of Emeth. In the verses that open each of the principles speeches in Job, (3:2, 4:1, 6:1, etc.) there are only three or four words, and we find that either a ravia (in the three-word verses that introduce Elihu or Job’s speeches) or a ravia mugrash (in the four-word verses that introduce the others with the longer names) precedes the final word, even though that final word is accented on its penultimate syllable. This can be explained by the perhaps-necessary proposition that every single verse needs at least one internal disjunctive trop, and there is no other place to put one in those verses, or that the final word actually is a “long” word, and we are just left with the question as to why “way-yo-MAR,” which is normally accented milra’, is here accented mil’eil, like its counterpart way-YO-mer, which has the same meaning, but normally appears at the beginning of a phrase. I hope the readership has any insights regarding this matter.

An opposite exception is in Job 6:4, whereby the “long” word YA-‘ar-CHU-ni is still connected to the previous word. I can hypothesize that this word should be considered short, as it was once pronounced with “only” two countable syllables, as though vowelized thusly: יַעְרְכוּנִי, ya’-R’CHU-ni.

….

One will also take note of the fact that in the Mechon Mamre edition (the online edition from which I borrowed these visual aids) and the various MHK editions edited by R’ Breuer, some verses have ordinary ravia’s instead of the ravia mugrash. For example, in the last verse of Psalm 150 above, the penultimate word has a ravia, but in the various Koren publications, for instance, and other traditionally Ashkenazi texts, those words also have a ravia mugrash. Apparently, R’ Breuer was of the opinion that a ravia mugrash can only appear in verses that already have an ethnah (or one of its replacements). The others do not subscribe to such a rule. Also, I find it interesting that in verses like those that conclude the last five psalms, we find a striking pattern that effectively divides the verse into three parts, instead of the usual two. Most verses in the Psalms follow the symmetrical division pattern, with the half-way point marked by an ethnah, and the quarters marked by a d’hi and ravia mugrash, respectively, but in these cases, the ordinarily symmetrical verse has the climactic Hallelujah added at the end, and because the ravia (mugrash) has to come before the silluq, what would have been the silluq is downgraded to a ravia mugrash, necessitating the downgrading of the the ethnah at what would have been the verse’s midpoint, resulting in it also receiving a ravia. This dispute between the publishers and the phenomenon of the verse being effectively divided into three by the ravia’s indicates to me that for our purposes both types of ravia (ordinary and mugrash) have the same punctuational value, and that in whatever theory we use to explain the hierarchy among the ta’amei emeth, the simple analogy of emperors, kings, viceroys (primary, secondary, and tertiary disjunctives), etc., that features in the other books of the Bible is not adequate for the books of Emeth. For example, in his introduction to the Daat Mikra Psalms, R’ Breuer wrote about how there are no “emperors” in ta’amei emeth, except for the silluqim, and how both the ravia and ethnah are on the same level, both being “kings.” I would like to offer that if we must use the nomenclature and analogies familiar from the other books, the silluq and oleh w’yoreid are the emperors, and the ethnah is the king, ravia’s are viceroys, etc., except that, in a radical departure from the rest of the Bible, most of the verses of Emeth, due to their shortness, have only one emperor, the silluq, and often the kings are also missing, as in those verses in which, as pointed out by R’ Breuer, some sort of ravia takes the ethnah‘s place because there are not enough words proceeding it that can be furthered divided.

One should also note how in the following two verses,

:וַיְדַבֵּ֣ר יְהוָ֔ה אֶֽל־אַהֲרֹ֖ן לֵאמֹֽר

and

:וַיְדַבֵּ֥ר יְהוָ֖ה אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֥ה לֵּאמֹֽר

the only difference is that the name of the object in the latter verse is slightly longer, and not even by a syllable. We see that the mere addition of a hei with a hataf patah lengthens the name Aharon enough so that it justifies upgrading the mercha before the silluq to a tip’ha, and the tip’ha that was already marking the Divine Name to be upgraded to a zaqef. Not only would this not fly in Emeth, as I have mentioned before, this shows the general tendency of the cantillation in most biblical books to have more disjunctives, especially when close to the “emperors,” whereas in Emeth the tendency is toward more conjunctives, especially as words get closer to the primary disjunctives. It is telling that the silluq, ethnah, zaqef, and tip’ha of most of the Bible have at most two words in their immediate domains connected to them by the trop, whereas the lesser disjunctives, e.g. the pazer, t’vir, and pashta are often preceded by three and sometimes four words marked with conjunctives. A comparison of similar words and phrases indicates for example, that the disjunctive t’vir of the rest of the bible is often converted to a conjunctive in Emeth.

….

In the rest of the books of the Bible, this idea that the sh’wa na’ forms one syllable with that which follows is often preserved in the phenomenon of the athei me’rahiq. In the second reading of Wayeira, we have the combination ha-LI-la L’CHA, whereby the lamed of l’cha receives a dagesh because it is part of an accented syllable that is immediately preceded by a connected word that ends with an unaccented qamatz in an open syllable.

Yet, there is also the phenomenon that a rule that distinguishes between two possible trops is even more specific than syllable count; sometimes, for instance, whether a word is marked with a qadma or munah, both conjunctives, depends on whether that word is accented on its very first letter, and that, in turn, effects the subsequent disjunctive. Two ready examples are Deuteronomy 15:7, V’CHA, and 17:18, w’CHA-thav. Words like these are either marked 1.with a munah if accented on their first letters, or 2. marked with a qadma if accented on any other letter. These examples show how exactly this rule is followed, as in both of them the first (compound) syllable is accented, but that is not sufficient to allow for the munah. Consequently, the following words are then, despite their being eligible to receive a gershayim, marked with a geresh, as there can not be a word marked with gershayim immediately following a word marked with a qadma.

With this in mind, we can understand an unusual difference of opinion. In Numbers 33:9, most of the tiqqunim have the words שתים עשרה marked with a qadma and azla (geresh). Had the word esreh appeared alone, (which technically could not happen because the word, as vowelized, only exists in conjunction with another,) it would have been marked with a gershayim because it is accented on its latter syllable, but because the word שתֵּים, which by our definition is monosyllabic, is not accented on its first letter, it therefore receives a qadma, which in turn converts the gershayim on עשרה into a geresh. (The word gershayim itself is unusual in that if it or any word of its mishqal were to appear in the Bible, it could never be marked with a gershayim precisely because it is accented mil’eil! It is very odd that thousands of young men are taught the trop by singing their names, thus becoming familiar with the “ger-sha-YIM.”) However, in MHK publications and in the Mechon Mamre edition, שתֵּים is marked a munah, and this makes perhaps more sense, as in the words שְתַּיִם, שְתֵּי, and שְתֵּים the taw is still strong, indicating the tradition that in these words, the sh’wa under the shin is not pronounced na’ and it would have been more appropriate for me to represent שְתֵּים as shteim, without the apostrophe I have been using to represent the sh’wa na. If the shin is indeed read in one consonant cluster with the taw, then this word is now accented on its very first letter (along with all four of its letters), thus calling for its trop to be a munah and not a qadma. In Diqduq Eliyahu and Lehem Habikkurim, this strange circumstance is illustrated by placing a phantom alef vowelized with a short vowel before the shin, thus making the shin appear to close a syllable and “immobilizing” its sh’wa. In a similar word, the singular masculine form of the imperative “drink,” שְתֵה, the shin is pronounced with a sh’wa na’ and therefore the taw is weak, while when the word שְתֵּי is prefixed with a mem, e.g., in Judges 16:28, indicating the contracted word מִן, the shin does receive a dagesh to compensate for the missing nun, making its sh’wa a sh’wa na’, and the taw does lose its dagesh.

Taking Issue with the Ish Matzliah

Rabbi Mazuz is the leading authority on all things grammatical, and it is a testament to his influence and greatness that two of his more questionable opinions, opinions that can not be reconciled with the traditions we have received, have become more and more popular, and is partly attributable to the fact that the tiqqun published by his students, Tiqqun Qor’im Ish Matzliah, and the subsequent Hummash of the same name for synagogue use have become fixtures in many synagogues.

The first involves the public reading of Genesis 35:22, the Reuben incident. According to the traditional practice, this verse describing Reuben’s actions is combined with the next verse (what should be 35:23, “And the children of Israel were twelve,” but in many editions is not numbered) thus eliminating its silluq, the Torah reader’s cue for the Targum reader, depriving the Targum reader a chance to actually read the translation to the former verse aloud, and when he hears the silluq of the latter verse, he only reads the Targum thereto. The author of the weekly letter “Tamey Torah” (spelled in Hebrew טעמי תורה, tameytorah@gmail.com) has pointed out in the name of the Rabbi Jacob Emden that this is the explanation for the alternate sets of trop that accompany the Decalogue, both iterations of which are traditionally read publicly in the ta’am elyon, a set of trop which recombines the traditional verses, i.e. rearranges the silluqim, such that some verses are thereby combined into one verse, whereas another verse is divided into multiple short verses, thus cuing to the Targum reader to read his lines after individual commandments and not actual verses. The standard set of trop is referred to as the ta’am tahton, and the usual systems of numbering the verses follow it.

For centuries now, most Jewish communities have not been reading the Targum along with the public Torah reading, and based on this explanation, there is no longer any reason for us to continue reading these three sections with the ta’am ‘elyon, and indeed there are places in which the practice of reading the Decalogue with the ta’am ‘elyon has been suspended. However, in places where the Targum is still read publicly, this upholds the talmudic imperative to not translate the account of the Reuben incident (M’gilla 4:10, Laws of Prayer and Torah Reading 12:12). Rabbi Emden’s understanding is even mentioned by Rabbi Mazuz in his introduction to his tiqqun, yet, it was his father’s practice (see Tamey Torah for written sources) to read Genesis 35:22 twice, once on its own and once connected to the next verse, in order to thereby read the verse with both sets of trop, as though to satisfy all of the opinions because we can not know which is the correct set of trop to follow. Tamey Torah has documented a number of sefarim, all of North African origin, that record this practice, which, aside from the fact that it utilizes the Reductio Ad Opinionibus At Dissiderent fallacy instead of trying to come to sort of halachic solution, has the negative consequence of now having Reuben’s incident read in front of native Hebrew-speakers twice, ensuring that they clearly hear the verse as is, and maybe even provoking them to look into it further, because attention has now been drawn to it. In both this case and the next, it is surprising that the Lehem Habikkurim “died from a kashya” and altered the practice, because in other lands, the answer to his kashya (“why are there two sets of trop?”) had already been offered and accepted, thereby upholding the traditional practice. Tamey Torah also notes that the Vatican manuscript they claim as a source is misunderstood: its marginal note is merely pointing out the existence of two sets of trop, and does not literally mean that both sets should somehow be read publicly.

As a side note, the other peculiarity found in the Vatican manuscript, indicating that Genesis 35:22 should feature a zarqa–segol series in the ta’am elyon, was also included in the tiqqun. Now, there are two competing schools of thought regarding what exactly a segol is supposed to be:

- Segol is a disjunctive trop on the level of an ethnah, and together they divide the verse into three parts, the first third concluding with the segol, the second with the ethnah. This explains why the segol always precedes the ethnah. (I know of only one verse in the Bible that has a segol but no ethnah.) When examining many verses, you can see that this makes a lot of sense, and is attributed to the Ibn Ezra and others, and is also endorsed by Rabbi Mazuz.

- Segol is a disjunctive on the level of a strong zaqef, and when a verse calls for many trops of that level, the first becomes a segol, under specific conditions. Jacobson brings a number of verses, including I Samuel 5:3-4 to illustrate this, and this is the position of Rav Breuer, among others, and explains why the segol‘s second mishneh is a ravi’a and not a zaqef, but it does not explain why segol is always before the ethnah.

According to the common tradition, Genesis 35:22 is to be read thusly:

:וַיְהִ֗י בִּשְׁכֹּ֤ן יִשְׂרָאֵל֙ בָּאָ֣רֶץ הַהִ֔וא וַיֵּ֣לֶךְ רְאוּבֵ֔ן וַיִּשְׁכַּ֕ב אֶת־בִּלְהָ֖ה פִּילֶ֣גֶשׁ אָבִ֑יו וַיִּשְׁמַ֖ע יִשְׂרָאֵֽל

and the subsequent verse, which as I mentioned, is not independently numbered in many editions, appears thusly:

וַיִּֽהְי֥וּ בְנֵֽי־יַעֲקֹ֖ב שְׁנֵ֥ים עָשָֽׂר׃

Now, there are two main ways we could have combined these verses into one long verse and preserve the hierarchy of the trop:

- The first verse is now only half a verse, and therefore, it’s silluq is downgraded to an ethnah, and its z’qefim and tip’hoth should be downgraded to pashtoth, r’vi’im, t’virim etc.,

or

- being that the latter verse has no ethnah, we could perhaps divide the combined verse into thirds, with the first verse containing the first two thirds, and its silluq becoming an ethnah and its own ethnah becoming a segol, but, as pointed by R’ Breuer and others, even if one were to assume that a segol is a disjunctive on the level of an ethnah, there is no such thing as a segol in such proximity to an ethnah. Therefore, this possibility is ruled out.

Yet, in the original verse, the zaqef on the word ההִוא is the strongest internal disjunctive after the ethnah of אביו, and when the verses are combined, because the original ethnah is downgraded, it stands to reason that the zaqef of hahi should have been downgraded to a ravia, and certainly not upgraded to a segol as it has been in the Tiqqun Ish Matzliah. On the contrary, if the Reuben verse is then extended by a new phrase that is “ruled by an emperor,” then the segol should at least be placed where the Reuben verse’s ethnah appeared, and I would therefore argue that if anything, we could only entertain a segol on the word hahi in the ta’am tahton of that verse.

Elsewhere in the tiqqun, the words ohela (genesis 18:6 and elsewhere) and tzo’ara (ibid 19:23) are, in accordance with the opinion of the Lehem Habikkurim, accented on their last syllables, o-he’LA and tzo-a’RA’, respectively, whereas in most tiqqunim, the words are accented on their first syllables, as is seemingly indicated in the oldest manuscripts, O-he’la and TZO-a’ra’. The argument for this position is as follows: Normally, the addition of an unaccented suffix qamatz-silent hei is an alternate form of the directional el or the prefix lamed (the same suffix when accented indicates femininity). “To Hebron” can either be el hevron, or l’hevron, or hevrona. In the latter case, the accent stays on the syllable that is normally accented, and the additional syllable formed by the qamatz and silent hei is not accented. Note also what happens to a word like goshen, which is of the same mishqal as tzo’ar and ohel. The normal pronunciation of the word is GO-shen, and when the directional is appended, it becomes GOSH-na, with the shin now closing the strong vowel of the accented syllable, but in the case of these two words, the presence of the guttural letter vowelized with a hataf, hei with a hataf segol and ‘ayin with a hataf patah, respectively, creates what appears to be a third syllable. Now, according to the rules of grammar with which we are familiar, those gutturals can not receive the accents because they have hatafim, and no hataf or sh’wa na’ is accented. Further, and this is the crux of the dispute, the first syllables of these words should not receive the accents either because that would result in words that are primarily accented too far away from the end of the words, and they are vowelized with holam, necessitating the subsequent guttural letters to be vowelized with forms of hataf vowels, themselves types of shwa na’, which according to another rule, can not follow a full vowel, a tnu’a g’dola, that is accented. Normally, Hebrew words are accented milra’, on the last syllable, whereas in some cases the word is mil’eil, accented before the last syllable, but even in those cases, the accent is at least on the syllable right before the last. There is no such thing as a word accented on a syllable two or more syllables away from the last syllable, and when there is a full vowel in an accented syllable, it can be closed by a shwa nah. For example, in אומרים o-m’RIM, the accented syllable has a hiriq gadol and is closed by the (unwritten) shwa nah of the mem, and in אומר o-MER, the tzeirei of the accented syllable is closed by the shwa nah of the reish.

However this argument is mistaken, because, as we have now learned, consonants, whether guttural or not, when vowelized with sh’wa na’ or any form of hataf do not count as syllables. Therefore, in the words ohela and tzoara, it is not the case that the first of three syllables is accented. Rather, it is just that the first of two syllables is accented. Also, because this first argument could be rejected by the editors of the tiqqun because they may not hold of this theory of explaining the vowels, it must be pointed out that even according to their own theory, when words do have full vowels in their final, accented and closed syllables and the final consonant is a pronounced guttural letter (‘ayin, heth, or a non-silent (“mappiq“) hei), then we add a phantom patah between the vowel and the consonant. If words like ohela and tzo’ara were to follow this model, we would have to pronounce them like אֹ ַהְלָה Oah-la and צֹ ַעְרָה TZOa’-ra, thus adding another seeming syllable to the word. (I added spaces within these words to show where the patah sound would be inserted. In words like תפוּחַ most people know to articulate the patah between the shuruq and the final heth.) In a word like GOSH-na, we would not be confronted with any problem because we already have a precedent for closing a holam‘s accented syllable with a shin sound without having to add a phantom patah, e.g., ראש, rosh. The truth is that in these unusual words, which are ideally accented on their first syllables which feature full vowels closed by guttural consonantal sounds, we have few options.

I welcome whatever insights the readers can offer.

* For almost twenty years, I have followed the Soncino Talmud’s convention of representing the waw as a “w” and thaw as “th” in transliteration. This, despite its unpopularity, eliminates many ambiguities and more accurately reflects the proper pronunciation.