Keter Shem Tov: A Study in the Entitling of Books, Here Limited to One Title Only

Keter Shem Tov: A Study in the Entitling of Books, Here Limited to One Title Only[1]

by Marvin J. Heller

Entitling, naming books is, a fascinating subject. Why did the author call his book what he/she did? Why that name and not another? Hebrew books frequently have names resounding in meaning, but providing little insight into the contents of the book. This article explores the subject, focusing on one title only, Keter Shem Tov. That book-name is taken from a verse “the crown of a good name (Keter Shem Tov) excels them all (Avot 4:13). The article describes the varied books with that title, unrelated by author or subject, and why the author/publisher selected that title for the book.

- Simeon said: there are three crowns: the crown of Torah, the crown of priesthood, and the crown of royalty; but the crown of a good name (emphasis added, Keter Shem Tov) excels them all (Avot 4:13).

“As a pearl atop a crown (keter), so are his good deeds fitting” (Israel Lipschutz, Zera Yisrael, Avot 4:13).

Entitling, naming books, remains, is, a fascinating subject. Why did the author call his book what he/she did? Why that name and not another? Hebrew books since the Middle-Ages often have names resounding in meaning, but providing little insight into the contents of the book. A reader looking at the title of a book in another language, more often than not, is immediately aware of the book’s subject matter. This is not the case for many Hebrew titles, the name having been selected by the author for any one of a number of reasons, least of all the book’s subject matter, but rather the intention is/was to give the book “the crown of a good name (Keter Shem Tov).”

Book titles have been addressed in both books and articles. Menahem Mendel Slatkine wrote a two volume work, Shemot ha-Sefarim ha-Ivrim: Lefi Sugehem ha-Shonim, Tikhunatam u-Te’udatam (Neuchâtel-Tel Aviv, 1950-54) on book names; it has been the subject of encyclopedia articles in both The Jewish Encyclopedia and the Encyclopedia Judaica; and such authors as Abraham Berliner, Joshua Bloch, and Solomon Schechter have written articles on book titles, all this apart from this subject being mentioned in passing in numerous other works. I too have addressed the subject, first in “Adderet Eliyahu; A Study in the Titling of Hebrew Books,” describing about thirty books with that single title, two only related to each other, and in “What’s in a name? An example of the Titling of Hebrew Books,” describing varied books taken from a single verse “Your neck is like the tower of David built with turrets, on which hang one thousand bucklers, all of them shields of mighty men (Song of Songs 4:4).[2]

What then is the justification for yet another article on the same subject? It is, as suggested above, the allure of how authors of varied unrelated works came to entitle their books, reflective of their intellectual or emotive processes or objectives. The title selected here, Keter Shem Tov, unlike Adderet Eliyahu, is not the title of as large a number of books, but the titles here are certainly as varied as those in the previous articles. Indeed, the works so entitled are sufficiently different, again providing insight into authors’ thoughts and, perhaps, an article of interest to the reader. We will not attempt to second guess or analyze an author’s motives, all of whom intended their book to have the crown of a good name (Keter Shem Tov), but rather we will let the authors speak for themselves when describing their books

In several instances, books are so entitled as to reflect the author’s name, Shem Tov. The use of a line from Avot, to reiterate the injunctions noted previously (“Adderet”), rather than directly using the author’s name, is to avoid violating R. Judah ben Samuel he-Hasid of Regensburg’s (c.1150-1217) proscription to not do so, so as to not benefit from this world, thereby decreasing one’s portion in the world to come, or to not reduce their offspring and the good name of their progeny in this world.[3] The Roke’ah (R. Eleazar ben Judah of Worms, c. 1165–c. 1238), however states at the beginning of the introduction to his Roke’ah, that everyone should inscribe his name in his book, as we find in the Tanna de-Vei Eliyahu.[4] Indeed, the Sefer ha-Roke’ah, is so entitled because the numerical value of the family name, Roke’ah (רקח=308), equals his personal name, Eleazar (אלעזר=308). It is, therefore, permissible to allude to the author’s name, for example, a Shem Tov using the title Keter Shem Tov, a quotation from Avot. Indeed, a substantial number of the books described here refer to the author’s name.

Our selection encompasses homilies on the Torah, Kabbalah on the Tetragrammaton, halakhah and minhagim (customs), the sayings of the Ba’al Shem Tov, in praise of Sir Moses Montefiore, a letter on behalf of the Jewish community in Tiberias, and a highly unusual work on the Dead Sea scrolls. Finally, this article is a vignette, no more no less, an insight into and, in a manner of speaking, a photograph of one manner of how Hebrew books are named.

Several caveats. First, our Keter Shem Tovs are organized within subject categories, beginning with 1) discourses, both literal and kabbalistic on the Torah, followed by 2) halakhah and minhag (custom), 3) biographical and related anecdotal works, 4) miscellanea, all ordered chronologically within category, and concluding with 5) a brief summary. Secondly, our approach will be somewhat expansive, the various Keter Shem Tovs giving us entry into related aspects of Hebrew printing and Jewish history. Lastly, while the number of works entitled Keter Shem Tov is not large, that notwithstanding, our examples are an overview and not meant to be all inclusive or comprehensive but intended as an interesting insight into an aspect of Hebrew book practice.

I Discourses, Literal and Kabbalistic on the Torah

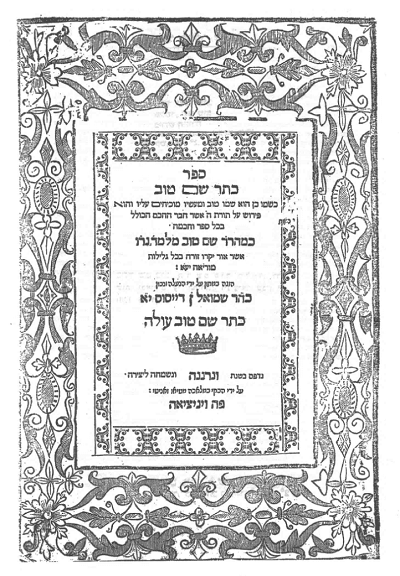

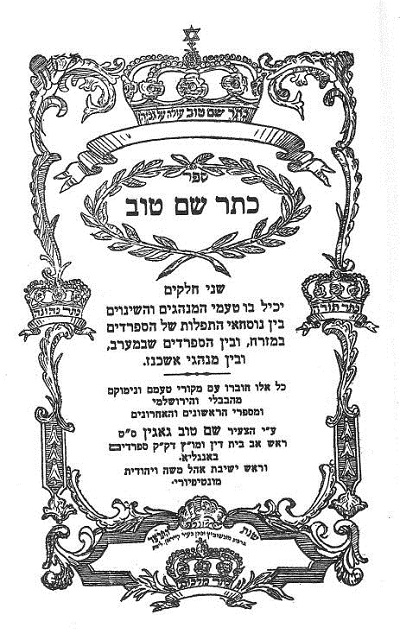

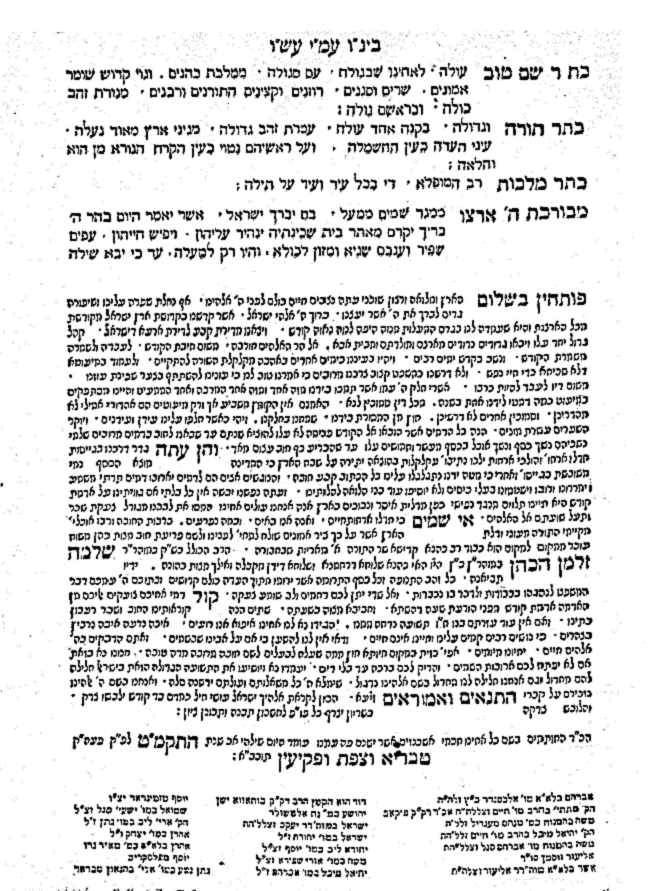

Keter Shem Tov, R. Shem Tov ben Jacob Melamed, Venice, 1596: Our first Keter Shem Tov is a commentary on the Torah by R. Shem Tov ben Jacob Melamed. It was printed in Venice (1596, 20: 136, 16 ff.) at the press of Matteo Zanetti. This Zanetti, a member of the famous Venetian printing family of that name, established his print-shop on the Calle de Dogan, publishing seven books from 1593 to 1596. Among his titles, in addition to Shem Tov Melamed’s Keter Shem Tov, are R. Nathan Nata Spira’s (Shapira) Be’urim, R. Bezalel Ashkenazi’s responsa, and R. Solomon le-Bet ha-Levi’s Divrei Shelomo.

The title page has the decorative frame employed by Zanetti on several of his books with a smaller frame in the center about the text. The title-page states that,

Keter Shem Tov

As is its name so is his name good and his deeds confirm it of him. It is a commentary on the Torah of HaShem written by the sage, the complete, in every book and wisdom.

Shem Tov Melamed

Whose precious light shines throughout [may

God shield him].

Edited patiently by the lofty and exalted

Samuel ibn Dysoss [may God watch over him]

Keter Shem Tov excels

Printed in the year, “that we may rejoice ונרננה (5356=1596) and be glad [all our days]” (Psalms 90:14) from the creation.

The introduction, from a student of the author, R. Samuel ben Solomon Segelmassi follows (2a), then a page of verse from the editor Samuel ibn Dysoss, the text (3a-136a), his apologia (136b), indexes (1a-16a), errata (16a), and the colophon (16b), which states that it was completed, “on the very day that Moses went up to the firmament (6 Sivan) and the Egyptians drowned in the sea (21 Nissan), in the year, “Then he saw it, and declare it ויספרה (5356=1596) (Job 28:27), from the creation.” It is unclear why there are two apparently contradictory completion dates. The text is in two columns in rabbinic type, excepting headings and initial words.

In the introduction Samuel ben Solomon writes that one who knows matters in truth and faithfully,

“shall come back with shouts of joy” (Psalms 126:6), “to perceive the words of understanding” (Proverbs 1:2) and this is the first intent of every man who presumes in his heart (Esther 7:5) to write “goodly words” (Genesis 49:21) in a book to leave after him a blessing. . . . It is a commentary on the holy Torah, “high and lofty” (Isaiah 6:1, 57:15), on each and every parshah . . .

The introduction continues that it contains derashot (discourses) according to the literal meaning, casuistic (pilpul), and very sharp. In the following paragraph we are informed that not everything that was said on every parshah was printed because of financial restraints. In the apologia ibn Dysoss adds a familiar plaint for the period, type set late erev Shabbat could not be properly corrected. Moreover, the compositors, not Jewish and not fully familiar with Hebrew and Hebrew letters, did that which was right in their eyes, and for which he should not be held responsible.

That the title clearly alludes to the author’s name, R. Shem Tov ben Jacob Melamed, is further suggested by the last line of verse at the end of the introduction, which states that “you will find that the crown of a good name (KETER SHEM TOV) excels them all. This is, as noted above, that authors’ names were frequently employed in book-titles, but, in keeping with the injunction of R. Judah he-Hasid, indirectly, here by referencing a quote from Avot.

Shem Tov Melamed was also the author of Ma’amar Mordekhai (Constantinople, 1585), a commentary on Megillat Esther, printed by Joseph Jabez. Melamed is described on the title of this work as a physician.

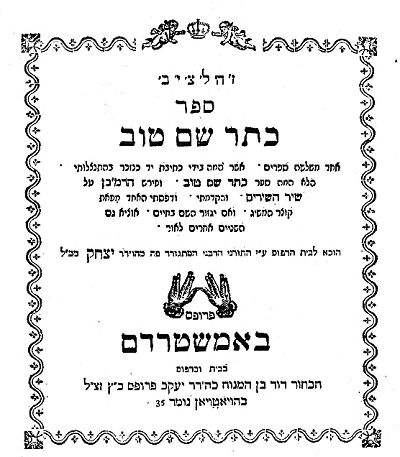

Keter Shem Tov, Amsterdam, R. Abraham ben Alexander (Axelrad) of Cologne, c. 1810-16: A kabbalistic Keter Shem Tov on the Tetragrammaton by R. Abraham ben Alexander (Axelrad) of Cologne (13th century). In Judaism the Tetragrammaton, the four letter divine name, is not directly expressed but instead referred to with a euphemistic name for God. The title-page describes this Keter Shem Tov as,

זהלציב [This is the gate of the Lord: the righteous shall enter through it] (Psalms 118:20)

Sefer

Keter Shem Tov

One of three books in my hand in manuscript, as described in my apologia. They are Keter Shem Tov and the commentary of the Ramban (R. Moses ben Nahman, Nachmanides, 1194–1270) on Shir ha-Shirim (Song of Songs). I have first printed one book only due to limited means. If the Lord will so decree I will publish the other two books. . . .

Although the title-page refers to three books two only are mentioned. The third work, noted in the editor’s apologia, is a commentary on the Merkavah of Ezekiel. Keter Shem Tov is not dated, so that various bibliographic sources date it as 1810 or 1816. The title-page is embellished by the Proops’ family press-mark, consisting of the kohen’s spread hands at the time he pronounces the priestly blessing. This edition of Keter Shem Tov (80: 5, 7 ff.) was printed in Amsterdam by David ben Jacob Proops. The Proops’ press, founded by Solomon Proops in 1704, was the longest lasting and most productive of the Hebrew printing-houses in Europe in the eighteenth century; it would continue to print Hebrew books until the mid-nineteenth century when, in 1869, the widow of David Proops sold the press to the Levissons, who printed until 1917.

Abraham, a student of R. Eleazar ben Judah of Worms (c. 1176–1238, Roke’ah), traveled through Spain between approximately 1260 and 1275, where he reportedly studied with R. Solomon ben Adret (Rashba, 1235–1310), the latter praising Abraham’s oratorical skills. Keter Shem Tov, as noted above, deals with the Tetragrammaton and also the Sefirot, addressing sacred names, using gematriot and synthesizing the mysticism of the Ashkenaz pietists (Hasidim) and Sephardic Kabbalistic methodologies.[5] Here too the reason for the title is not explicitly stated but, given the subject matter, is obvious.

This is not the first printing of Abraham ben Alexander’s Keter Shem Tov. It appeared earlier, included in a collection entitled Likkutim me-Rav Hai Gaon (Warsaw, 1798), under the title Ma’amar Peloni Almoni (ff. 26-32a). It has since been reprinted several times, often among collections of other works.

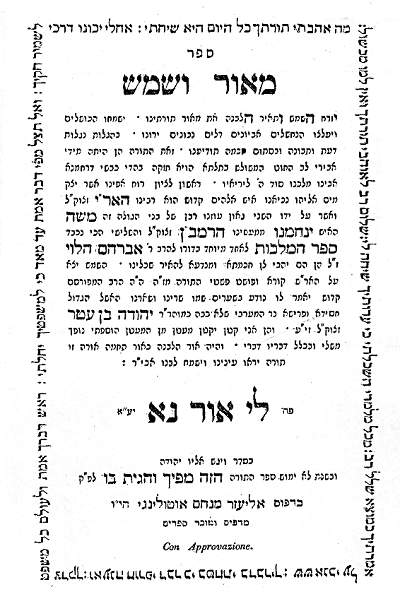

Ma’or va-Shemesh, R. Shem Tov ben Abraham ibn Gaon, Livorno, 1839: The next Keter Shem Tov, by R. Shem Tov ben Abraham ibn Gaon, is also a kabbalistic discourse on the Torah, this part of a larger multi-volume work entitled Ma’or va-Shemesh (Livorno, 1839, 80: [3], 3-11, [1], 128 ff.) printed by Eliezer Menahem Ottolenghi. The inclusion of Ma’or va-Shemesh represents a more expansive view of works entitled Keter Shem Tov as it is an independent work included in a larger collection of dissertations. The author (compiler) of Ma’or va-Shemesh, R. Judah ben Abraham Coriat (d. 1787) of Tetuán, was a scion of a distinguished Moroccan family.

- Shem Tov ibn Gaon (c. 1287-c. 340) was born in Soria, Spain and went up to Eretz Israel in 1312, settling in Safed where he wrote most of his books. He was a student of R. Solomon ben Adret (Rashba, 1235–1310) and R. Isaac ben Todros (13th cent.). Best known of ibn Gaon’s titles is Migdal Oz, on Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah as well as several works in manuscript. Keter Shem Tov, his first book, was reportedly written in Spain, while Rashba was still alive.[6]

The title-page of Ma’or va-Shemesh has a frame comprised of verses, all from Psalm 119:

“O how I love your Torah! It is my meditation all the day” (Psalms 97);

“O that my ways were directed to keep your statutes!) (5);

“The sum of your word is truth; and every one of your righteous judgments endures for ever” (160);

“So shall I have an answer for him who insults me; for I trust in your word” (42);

“So shall I have an answer for him who insults me; for I trust in your word” (162);

“I have more understanding than all my teachers; for your testimonies are my meditation” (99); “Great peace have those who love your Torah; and nothing can make them stumble” (165).

An additional verse is employed for the date, “This Book of the Torah shall not depart from your mouth; but you shall meditate on it הזה מפיך והגית בו (599 = 1839)” (Joshua 1:8). The title too is from Psalms, “The day is yours, the night also is yours; you have prepared the light and the sun (Ma’or va-Shemesh)” (Psalms 74:16).

The text of the title-page notes several of the authors whose kabbalistic works comprise Ma’or va-Shemesh, notably the Ari ha-Kadosh (R. Isaac Luria, 1534 – July 25, 1572), R. Moses ben Nahman (Ramban), Sefer ha-Malkut, and R. Judah ben Attar, Coriat’s maternal grandfather. The verso of the title-page has a pressmark, a lion rampant holding thistle under crown and below it the phrase Gur Aryeh Yehudah. This device was used previously in Livorno by Eliezer Saadun. When employed by Ottolenghi the lion has been turned to face right, it having previously faced left.[7]

There are introductions from R. Elijah Benamozegh and Abraham ben Judah Coriat, the former comprised of five paragraphs, each beginning with the word Kol and concluding with Judah, the latter’s introduction comprised of eight paragraphs, each beginning with Ben and concluding with Av. The text is comprised of several kabbalistic works, among them Shem Tov ben Abraham ibn Gaon’s Keter Shem Tov (ff. 25-54a), here not explicitly stated but rather entitled Perush Sodot ha-Torah. Shem Tov was a kabbalist, who studied with the Rashba and R. Isaac ben Todros. He was greatly influenced by the Ramban (R. Moses ben Nachman), reflected in his Keter Shem Tov, which is a kabbalistic super-commentary on Ramban’s Torah commentary. Here too, the title comes from the author’s name, Shem Tov.

A small portion of ibn Gaon’s Keter Shem Tov was printed previously (ff. 41b-44a), in R. Jehiel ben Israel Luria Ashkenazi’s Heikhal ha-Shem (Venice, 1601), on the ten Sefirot, Likkutei Kabbalah Kadmonim.

This much expanded version of Keter Shem Tov is based on an 1810 manuscript prepared by R. Elijah Lombroso.

II Halakhah and Minhag

Keter Shem Tov, R. Shem Tov ben Isaac Gaguine, Kaidan, Lithuania, 1934: An encyclopedic work on the varied customs and liturgy of eastern and western Sephardim and Ashkenazim by R. Shem Tov Gaguine (Gaguin, 1884-1953). Gaguine, scion of a famous Moroccan Rabbinical dynasty which emigrated to Palestine from Spain, was a great-grandson of R. Hayyim Gaguin the first Hakham Bashi of Eretz Israel in the Ottoman Empire and a great-great grandson of the kabbalist Sar Shalom Sharabi. Gaguine, who received semicha (ordination) from R. Hayyim Berlin, served as a dayyan in Cairo, rabbi and dayyan in Manchester, England, Rosh Yeshivah of Judith Montefiore Theological College, Ramsgate, and, from 1935, as head of Sephardi Medrash Heshaim in London.[8]

This Keter Shem Tov is comprised of seven volumes, the first two published in 1934, and the last four published posthumously by his son Dr. Maurice Gaguine. The complete work has been republished several times.

As noted above, Keter Shem Tov is a comprehensive work describing the liturgy and customs of eastern and western Sephardim and of Ashkenazim, accompanied by detailed footnotes from the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds and later halakhic authorities. Although most of the entries explain more familiar customs, many are unusual. Example of the latter are:

The custom in [Eretz Israel and Syria, Turkey and Morocco] when the father, grandfather, father-in-law, one’s rabbi, or elder brother has an Aliyah, to stand on one’s feet until he returns to his place, and to go to them, kiss their hand and receive a blessing (I:213).

An unusual custom of the Sephardim in the city of Algiers is the phrase “marror zeh (this marror)” is said three times and then thrown to the ground, and afterwards picked up and returned to the ka’arah (Seder plate).[9]

Why is the marror called hasa or hazeret (lettuce or horse raddish)?

The Ashkenaz custom is to take, in place of hazeret a type of dry radish called in their language hrain, which is as sharp as mustard and does not have a bitter taste. The Sephardic custom is specifically hazeret. . . . (III: 158-59).

Keter Shem Tov, R. Avishai Taharani, Jerusalem, 2000: Another work on halakhah and customs, this most specific, described on the title-page as “a treasure of all the halakhot and personal customs concerning naming sons and daughters” by R. Avishai Taharani. The title-page continues that in it are explained the basic guidelines for giving names “by whose observance man shall live” (Leviticus 18:5, Ezekiel 20:11, 13, 21). Also addressed are the names that one should refrain from using.

In the introduction (pp. 1-23) to this two volume work, Taharani informs that he has so entitled the book, based on the injunction of the Roke’ah (above), as well as several other works. He has done so, however, with gematriot (numerical equivalencies) for “Avishai Taharani ben my lord and father Isaac אבישי טהרני בן לאדוני ואבי יצחק (977) which corresponds to Keter Shem Tov כתר שם טוב (977).” The text is wide ranging, comprehensive, and accompanied by detailed footnotes. Several examples of the more unusual entries in the text are:

If a father errs and calls his son or daughter with two names, forgetting that the additional name was given to another child, there are those who say that until thirty days he may change the name (I:118).

Some say that if one has a child from an unmarried woman, the child should be called with a name that predates [the time of the] Patriarch Abraham or with a name that is not customary, for example, Dan, so that he will be judged according to his problem. There are places that it is customary to give these names to those who are kosher and Heaven forfend one should come to question those who are kosher (I: 237-38).

Some say that one should not call [a child] with one of the names that predates the Patriarch Abraham, for example: Adam, Noah, and all who call by a name that predates the Patriarch Abraham is not in the category of one who “labors in the Torah, and does not give pleasure to his Creator” (cf. Berakhot 17a). (I:397-400).

It is permissible to shorten a name, whether for a son or a daughter, as long as that name is used only casually, and it is best to use the full name at least once a day in order that the short form dies not become customary (II:110-13).

In a lengthy footnote to the third entry concerning names that predate the Patriarch Abraham a source for the entry is given, ha-Mabit (R. Moses ben Joseph of Trani, 1500 – 1580). It is followed by a number of contrary sources by other prominent rabbis, and then a lengthy discussion. That this Keter Shem Tov has proven to be a relatively popular work is evident from the publication of two additional editions, the last in 2007.

Keter Shem Tov, Kollel Keter Shem Tov, Kiryat Bialik, 2002: Collection of discourses and responsa on Shulhan Arukh Hoshen Mishpat by rabbis from the Kollel Keter Shem Tov in Kiryat Bialik, located in the vicinity of Haifa. There is an introduction from R. Mahluf Aminadav Krispin, Chief Rabbi of Kiryat Bialik, followed by the text, comprised of nineteen articles, including one by the Rosh Yeshiva R. Solomon Shalosh. Examples of the articles are 5) “on the prohibition turning to secular courts” by R. Efied Hagibi, member of the Kollel; 6) finding a relative or one who is unfit among the judges by R. David Alharar, member of the Kollel; 9) witnesses who have fulfilled their charge” by R. Evied Elul, member of the Kollel; 11) “the obligation of rent after divorce, the portion in the residence” by R. Abraham Atlas, av bet din, Haifa; 14) “acquisition through forgiveness (relinquishment) by R. Solomon Shalaoh; and 19) “the wages of a worker and contractor who did not provide the agreed upon benefit” by R. Abraham Atlas.

The title-page numbers the volume as no. one, but it is not known whether additional volumes were published.

III Biographical and Related Anecdotal Works

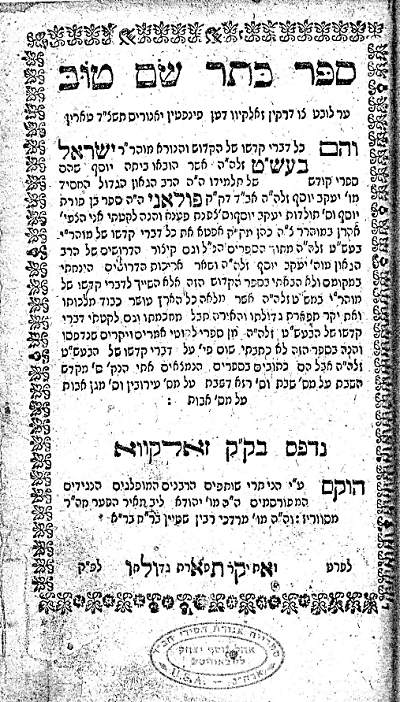

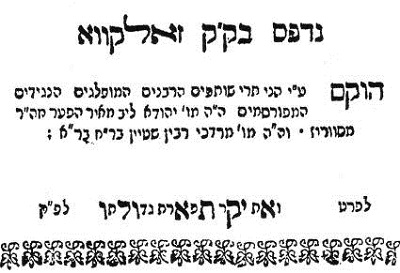

Keter Shem Tov, R. Aharon ben Zevi ha-Kohen of Apta, Zolkiew, 1794/95: The most popular of our Keter Shem Tovs, based on the printed editions, is the collection of tales and stories of the remarkable and astounding deeds of the Ba’al Shem Tov (R. Israel ben Eliezer, Besht, c. 1700–1760), founder of the Hasidic movement, as well as his recorded sayings, assembled from the works of his disciples. This collection of tales and sayings was assembled by R. Aaron ben Zevi Hirsch ha-Kohen of Opatow (Apta).

The book is in two parts, each with its own title-page but identical text, except that the first title-page is dated with a chronogram, the second title-page, printed a year later, is dated in a straightforward manner, תקנ”ה (555 = 1795). Perhaps the reason that the second title-page is so dated is that the first title-page exists in two forms, the rare first title-page, is dated “and the glory of his splendid majesty ואת יקר תפארת גדולתו (544 = 1784)” (Esther 1:4), which is incorrect, the book having been printed a decade later. The error was likely quickly caught, for the corrected and much better known title-page has the same chronogram, now reading ואת יקר תפארת גדולתו, the yod in the second word enlarged and emphasized, for a correct total of 554 (1794).[10] The variants are recorded separately in several bibliographic works.[11]

The title-page informs that that much of the contents are from the works of R. Jacob Joseph ben Zevi ha-Kohen av bet din of Polonnoye (d. c. 1782), the Ba’al Shem Tov’s leading disciple, that is, Toledot Ya’akov Yosef, Ben Porat Yosef, and Zafenat Pa’ne’ah, as well as discourses, also from other works. Among these latter sources are Likkutei Amorim and the sayings of the Ba’al Shem Tov, all collected by R. Aaron ben Zevi Hirsch ha-Kohen of Opatow (Apta).

In addition to the variations to the first title-page, the second title-page also exists in two formats, with, unlike the first title-page, some textual variations. Within the text of the book, despite Aaron ben Zevi Hirsch ha-Kohen’s comments that he has assembled the Ba’al Shem Tov’s words from the above mentioned titles, he did not, in fact, merely transcribe them in toto, nor did he distinguish which were the words of the Ba’al Shem Tov and those of Jacob Joseph.[12]

Keter Shem Tov has an approbation from R. Menachem Mendel of Liska, followed by the famed Iggeret Hakodesh, a letter from the Ba’al Shem Tov to his brother, dated Rosh Ha-Shanah, 1747, in which he relates that his soul ascended to heaven where he met with the Messiah, and then the text. This Keter Shem Tov, as noted above, has proven to be an enduring and popular work; it was printed soon after in Korezec (1797), Lemberg (1809) and several times afterwards there, in numerous other locations, and continues to be republished to the present.

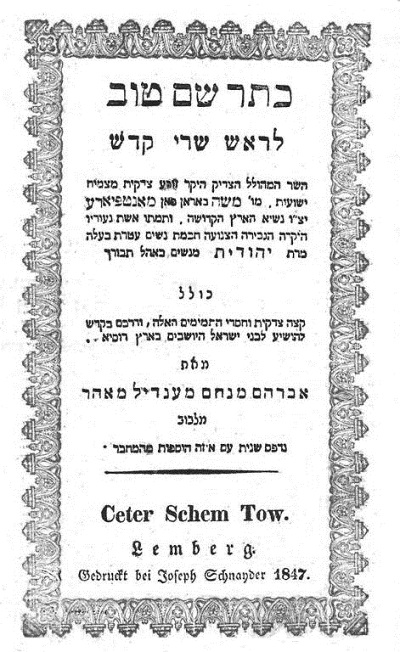

Keter Shem Tov, Abraham Menahem Mendel Mohr, Lvov (Lemberg), 1847: Sir Moses Montefiore (1784–1885) was one of, if not the most prominent member of English Jewry in the nineteenth century. Cecil Roth described him as “the most notable Jew, and indeed one of the most notable Englishmen, of the 19th century by virtue of his outstanding philanthropic work extending over a period of three-quarters of a century, into his venerable old age.”13 Montefiore traveled to the Middle East during the Damascus Affair, to Russia, Morocco, and Rumania on behalf of persecuted Jewry, as well as providing leadership and support of Jewry at home and in Eretz Israel. His indefatigable efforts on behalf of world Jewry are recorded and acknowledged in books, articles, and newspapers, several works entitled Keter Shem Tov.

The first Keter Shem Tov praising Sir Moses Montefiore is by Abraham Menahem Mendel Mohr (1815–1868), a scholarly maskil, author of a number of Hebrew and Yiddish books. The title-page states that it is,

Keter Shem Tov

For the chief, holy prince

The praiseworthy, the righteous, the dear, who sows righteousness and brings forth salvation. Our teacher, Moses Baron from Montefiore [May his Rock and Redeemer protect him], prince of the holy land. And the pure wife of his youth, the honorable lady, the modest, the wisdom of women “is a crown to her husband” (Proverbs 12:4), the lady Judith “blessed shall she be above women in the tent” (Judges 5:24). . . .

The title-page continues that the text includes some of the righteousness and perfect kindness on behalf of the Jews in Russia. A small book, (80: 16 pp.: Joseph Schnander), the text begins with verse, with the header “from Moses to Moses there was none like Moses” normally referring to Maimonides but here applied to Montefiore. The verse beginning,

“Moses ben Amram brought Israel out from the burdens of Egypt

and Moses Montefiore redeemed them from death to life.

Moses ben Amram “struck the rock, so that the waters gushed out” (Psalms 78:20)

and Moses Montefiore softened the heart of stone with “words of lips” (cf. II Kings 18:20, Isaiah 36:5). . . .

The volume concludes with a letter of appreciation from Sir Moses Montefiore.

A Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) version of Mohr’s Keter Shem Tov was printed in Salonika (1850, 80: 48, 53-80 ff.) together with two other works, Tiferet Yisrael on the Rothschilds, and Ma’aseh Eretz Israel on Eretz Israel from the destruction of the Temple to the nineteenth century. Among the many other works either praising or including a section on Montefiore are Kol Kitvei Rabbi Ya’akov Saphir ha-Levi (Jerusalem, 1934), the writings of R. Jacob Saphir (1822–1886), an emissary of the Jewish community in Jerusalem and the author of Even Saphir on the Jewish communities in such varied places as Yemen, Egypt, India, and India that he visited. In Kol Kisvei is a section entitled Keter Shem Tov Kenaf Renanim Sir Moses Monrefiore, accompanied by a cameo of Montefiore.

Yet another Keter Shem Tov about Montefiore was published by Hayyim Guedalla (London, 1884). The Hebrew title-page is followed by an English title-page that states,

The Crown of A Good Name

a brief account

of a few of the

Doings, Preachings, and Compositions

On

Sir Moses Montifieore’s Natal Day,

November 8th, 1883,

on which he was favored with a succession of telegraphic

Congratulations from the QUEEN OF ENGLAND and many

Eminent People of all Creeds.

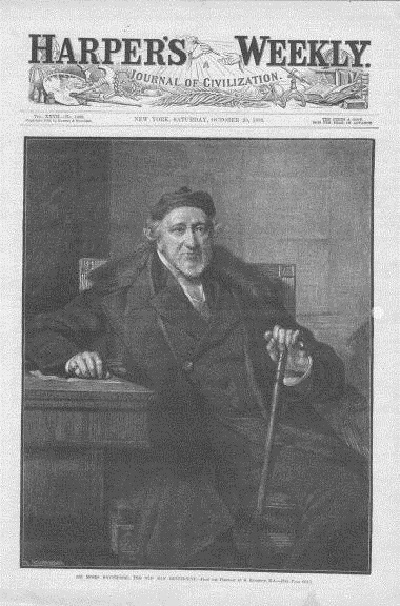

Below is the quote from Pirke Avot. The text includes congratulatory letters from the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh, many others, and special services in both Hebrew and English. In addition, many other publications relate to Moses Montefiore, among them, albeit this not directly pertinent to the article but of interest as a further example of how widespread the high esteem in which the venerable Sir Moses Montefiore was held, is the title page of the October 20. 1883 Harper’s Weekly Journal of Civilization (New York), with a full cover portrait of Montefiore.

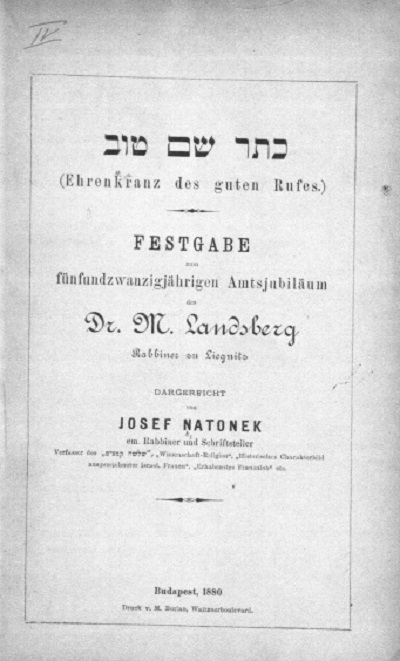

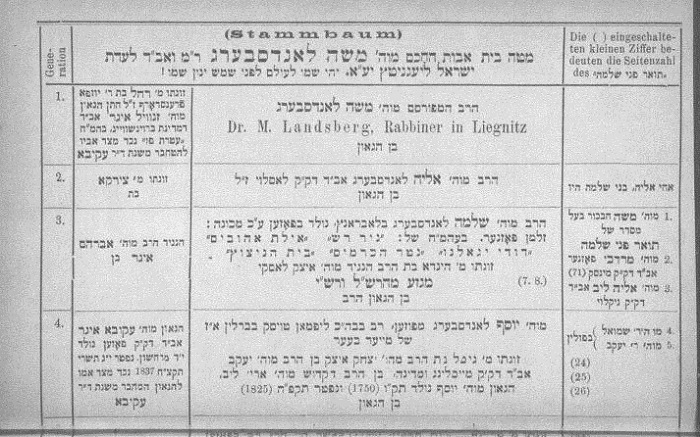

Keter Shem Tov (Ehrenkranz des guten Rufes), R. Josef Natonek, Budapest, 1880: German Keter Shem Tov by Josef Natonek in honor of Rabbi Dr. Moritz Landsberg (1824-80), son of R. Elias Landsberg (1800-79). Except for a Hebrew header the title page is entirely in German, as is the text (32 pp.), with only occasional Hebrew.

The title, Ehrenkranz des guten Rufes, is our “crown of a good name,” a Festgabe zum fünfundzwanzigjährigen Amtsjubilaeum des Dr. M. Landsberg, Rabbiner zu Liegnitz dargereicht von Rabbiner Josef Natonek em Rabbiner und Schriftsteller verfasser, that is a festive volume presented to Landsberger on the twenty-fifth jubilee of his service as rabbi in Liegnitz, by R. Josef Natonek (1813-92), a rabbi and author. Landsberg, doctor of philosophy educated in Berlin, became, in 1854, the rabbi of Legnica. Born in Rawicz, He served as rabbi for twenty-five years until his death in Liegnitz (Legnica, Silesia).[14] Landsburg was also the author of a number of studies on the history of medicine, particularly in ancient times, published for the most part in the journal Juno, published by von Henschel.[15]

At the end of the volume is a two page Stammbaum (family tree) of the Landsberg family.

IV Miscellanea

Keter Shem Tov, R. Solomon Zalman ben Zevi Hirsch ha-Kohen, Livorno, c. 1789: Our next Keter Shem Tov is a quarto sized page printed in Livorno in c. 1789 for the Hassidic Tiberius Kollel Ashkenazim. It informs that R. Solomon Zalman ben Zevi Hirsch ha-Kohen (d. 1799) is an emissary of the Merciful One and of us (the Ashkenaz Hasidic community of Tiberias). The letter is signed by twenty-one rabbis.[16]

The letter begins with a reference to Keter Shem Tov followed by a list of honorifics “but the crown of a good name (Keter Shem Tov) excels them all. To our brothers in the exile, a treasured people, ‘a kingdom of priests and a holy nation’ (Exodus 19:6), keepers of the faith, princes and chieftains, princes and leaders, ‘a lampstand all of gold’ (Zechariah 4:2) Torah scholars and rabbis.”

It informs about their joy in the merit to live in Eretz Israel. Until now they had relied upon support from the country from which they had come; but now, however, due to war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, they could no longer depend on that funding, so that they are now turning to Jews in other lands for support. Indeed, in describing the situation the letter notes the dire financial situation and that the land “‘is infested with bandits’ (Yevamot 115a, 122a) ‘the task masters hurried them’ (Exodus 5:13), they ‘lie in wait for blood’ (Micah 7:2). . . . ‘But now our soul is dried away; there is nothing at all (Numbers 11:6)’”

Solomon Zalman had traveled twice previously as an emissary to Russia (1779-81/1784-85), but this was his first trip to Western Europe. Avraham Yaari relates that Solomon Zalman’s undertaking was not without objection. The Sephardic community protested that the Hasidic community, which had previously received support from Eastern Europe, a venue now closed to them, was, by sending an emissary to Western Europe, entering into the domain of the general Tiberias community. The dispute was resolved several years later when joint representatives of both communities went to Eastern Europe.[17]

The letter begins with that part of the phrase from Avot referring to Keter Shem Tov intimating that a way one obtains the “crown of a good name (Keter Shem Tov)” is through good deeds and charity, which, as noted above, is “As a pearl atop a crown (keter), so are his good deeds fitting,” certainly appropriate for an appeal for the destitute community in Israel, the subject of the our Keter Shem Tov.

Keter Shem Tov, Shani Tzoref, Ian Young, Editors; Piscataway, NJ, 2013: A highly unusual Keter Shem Tov, this the proceedings of a conference on the Dead Sea scrolls held in memory of the late emeritus professor Alan David Crown in late 2011 at the University of Sydney, Mandelbaum House. This volume is part of a series entitled Perspectives on Hebrew Scriptures and its Contexts published by Gorgias Press, which describes itself as “an independent academic publisher of books and journals covering several areas related to religious studies, the world of ancient western Asia, classics, and Middle Eastern studies.” Among their subject matter is Ancient Near East, Arabic and Islam, Archaeology, Bible, Classics, Early Christianity, Judaism, Linguistics, Syriac, and Ugaritic.

Professor Alan David Crown (1932-2010) in whose memory this book was published, was Professor in Semitic Studies at the University of Sydney, and a renowned scholar and author. As noted on a website referring to him the title relates to the name Crown (Keter), for “He may have inherited the name Crown from his parents, but he earned the title ‘CROWN’ – the Crown of Torah, through his own merit, his sharp intellect and his deep respect for scholarship.”[18] The editors are Dr. Shani Tzoref, Ph.D., Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, New York University and currently a Qumran Institute Fellow, Seminar für Altes Testament, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, and Dr. Ian Young, Associate Professor, Chair of Department at the University of Sydney, Australia, teaching Classical Hebrew and Biblical Studies.

This edition of Perspectives on Hebrew Scriptures and its Contexts 20: Keter Shem Tov (x, 400 pp.) is comprised of sixteen articles on various subjects in the field of Qumran studies (Dead Sea scrolls) from scholars in the field. The articles encompass the development and phases of Qumran scholarship; textual transmission of the Hebrew Bible, including Samaritan texts and Masada Biblical Scrolls; reception of Scripture in the Dead Sea Scrolls; community and the Dead Sea Scrolls; and eschatology and sexuality in the So-Called Sectarian Documents from Qumran; and the Temple and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

V Summary

This concludes our survey of books with the title Keter Shem Tov. As noted above, the article is vignettes of books so entitled. There is no single pattern in the use of the title, it being applied to a wide variety of books. There are discourses on the Torah, both literal and kabbalistic, works on Jewish law and customs, biographic or anecdotal, and several miscellaneous works, among them an appeal for support of Jewish communities in the Holy Land and on the Dead Sea scrolls. The title Keter Shem Tov has been chosen because it refers to an author’s name, for example, R. Shem Tov Melamed, R. Shem Tov ibn Gaon, and R. Shem Tov Gaguine; bibliographical works such as those referring to the Ba’al Shem Tov, Sir Moses Montefiore, and Rabbi Dr. Moritz Landsberg; and more diverse works, such as one being the novellae of a Kollel, the Dead Sea scrolls, and even topically related as in R. Avishai Taharani’s Keter Shem Tov, which actually deals with laws and customs applicable to names.

We began by noting that the title of Hebrew books, unlike books in other languages, may have “been selected by the author for any one of a number of reasons, least of all the book’s subject matter; rather the intention is/was to give the book ‘the crown of a good name (Keter Shem Tov)’.” Indeed, not one book in this article, with the possible exception of Taharani’s Keter Shem Tov, indicates its subject matter by the title. What each of these examples do have in common, is the intent to associate the name of the author, subject, or even organization with the Mishnah in Pirke Avot, which states,

- Simeon said: there are three crowns: the crown of Torah, the crown of priesthood, and the crown of royalty; but the crown of a good name (emphasis added, Keter Shem Tov) excels them all (Avot 4:13).

[1] I would like to thank Eli Genauer for reading the article and his comments and my son-in-law, R. Moshe Tepfer, for his assistance and research in the National Library of Israel, including getting the 1789 Livorno illustration from

[2] Marvin J. Heller, “Adderet Eliyahu; A Study in the Titling of Hebrew Books,” in Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2008), pp. 72-91; idem. “What’s in a name? An example of the Titling of Hebrew Books,” in Further Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2013) pp. 371-94.

[3] Judah he-Hasid, Sefer Hasidim (Jerusalem, 1973), ed. Re’uven Margaliot, pp. 210-11, n. 367 [Hebrew].

[4] Eleazar ben Judah, Sefer Roke’ah ha-Gadol (Jerusalem, 1967), ed. Barukh Shimon Shneurson, p. 1 [Hebrew].

[5] Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah (New York, 1974), p. 51.

[6] Shimon Vanunu, Encyclopedia Arzei ha-Levanon. Encyclopedia le-Toldot Geonei ve-Hakhmei Yahadut Sefarad ve-ha-Mizrah IV (Jerusalem, 2006), pp. 2152 [Hebrew].

[7] Avraham Yaari, Diglei ha-Madpisim ha-Ivriyyim (Jerusalem, 1943, reprint Westmead, 1971), pp. 96, 174 no. 160, [Hebrew].

[8] Shimon Vanunu, Encyclopedia Arzei ha-Levanon. Encyclopedia le-Toldot Geonei ve-Hakhmei Yahadut Sefarad ve-ha-Mizrah IV (Jerusalem, 2006), pp. 2155-56 [Hebrew].

[9] In contrast, the Mishnah Berurah (477:1:5) quotes the Shelah ha-Kodesh who states that ” have seen people of status who kiss the matzah and the marror . . . all to cherish the mitzvah.”

[10] Such errors and their corrections are known as stop-press corrections. Sheets were proof read while the press-run was under way; while it certainly was preferable to correct the sheets before the run began, reading also took place while the run was under way. When the corrector would find an error he would stop the run, remove the forme, quickly correct the error, and resume printing. Unless substantial, stop-press corrections did not necessitate disposing of the previous sheet – four pages in a folio, more so in a smaller format – but rather both the altered states and the originals are used. In such a case, there will be variant copies of the book, consisting of sheets printed from forms in both the earlier and later states, as is the case here.

[11] The copy with the misdated title-page in the Chabad-Lubavitch Library is attractively bound in a soft brown leather, the cover stamped כתר שם טוב ב”ק אדמו”ר שליט”א, that is, it was in the private library of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, R. Menachem Mendel Schneeersohn (1902–94). The reading room librarian, R. Zalman Levine, informs me that to his knowledge this is the only book so bound, and that it “was given to the rebbe with this binding.

[12] Keter Shem Tov (Brooklyn, 1972), p. v [Hebrew].

[13] Cecil Roth, “Moses Montefiore, 1784-1885,” in Essays and Portraits in Anglo-Jewish History (Philadelphia, 1962), p. 262.+

[14] As an aside, Jewish settlement in Lieignitz can be traced to the Middle Ages, interrupted by pogroms, the first in 1447 due to a dispute between Elżbieta, Duchess of Legnica with Jewish bankers, who demanded that she return a loan. Liegnitz is best remembered for a battle that took place there in 1241, when a Polish-German Army lead by Duke Henry II of Silesia engaged invading Mongol near the town. The Mongols were victorious, collecting nine sacks of ears from their fallen enemies, all of whom perished.

[15] Klatzkin, Jacob and Ismar Elbogen, editors, Enyclopaedia Judaica: Das Judentum in Geschichte und Gegenwart 10 (Berlin, 1928-34), p. 619.

[16] The signatories are R. Abraham ben Alexander Katz of Kalisk; R. Matthias ben Hayyim; R. Moses ben Menahem Mendel; R. Jehiel Michal ben Hayyim; R. Moses ben Abraham Segal; R. Eliezer Sussman; R. Asher ben Eliezer; R. David he is the Katan, rav of Bohava Yeshain; R. Joshua ben Noah Altshuler; R. Israel ben Jacob; R. Israel ben Judah; R. Judah Leib ben Joseph; R. Moses ben Uri Shapira; R. Jehiel Michal ben Abraham; R. Joseph of Zimigrad; R. Samuel ben Isaiah Segal; R. Aryeh Leib ben Nathan; R. Aaron ben Isaac; R. Aaron ben Meir; R. Joseph of Poloskov; and R. Nathan Nata ben Eli of Brod.

[17] Avraham Yaari, Sheluhei Eretz Yisrael II (Jerusalem, 1951, reprint Jerusalem, 1997), pp. 619-28 [Hebrew].

[18] http://learning.mandelbaum.usyd.edu.au/about-us/alan-crown/