Further On A Forged Letter of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik

Further On A Forged Letter of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik

By Mosheh Lichtenstein

Rabbi Mosheh Lichtenstein is a co-Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Har Etzion.

He is a grandson of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik.

It was recently brought to my attention that various readers of the Seforim Blog have expressed skepticism regarding the determination that the letter found in President Chaim Herzog’s archives and supposedly written by my grandfather, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zt”l (hereafter, “the Rav”), is a forgery.

Moreover, some of the commentators have engaged in various conspiracy theories regarding the motivation and the accuracy of the claim that this is a fake letter. See here. Although I do not usually attempt to argue with such claims or engage conspiracy theorists and strongly suspect that penning this response will not necessarily convince those who refused to accept the original clarification, I will, nevertheless, attempt to present the evidence that the letter is indeed a forgery since I fear that future researchers may also question the denial and view the letter’s status as an unresolved issue.

Moreover, since there may be sincere individuals who are indeed skeptical of a forgery claim regarding a letter whose subject is a controversial figure and may suspect that there is an agenda behind the denial of the letter’s legitimacy, I am presenting the evidence for their review and evaluation. Thus, if those who expressed skepticism are indeed sincere and open to evaluating the evidence, it is my hope that they will review the evidence presented below and recognize that the letter is fraudulent.

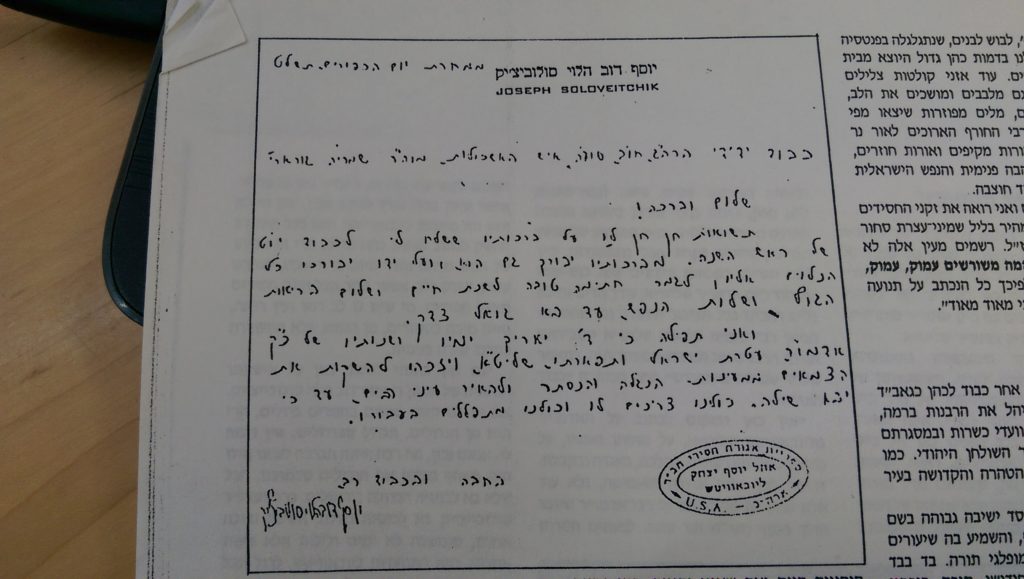

At the outset, I must re-emphasize what was clearly stated by the editors of the Seforim Blog (here); i.e. that the determination of our family members who saw this letter and judged it to be a “crude forgery” was entirely based upon an examination of the signature, stationery and other such considerations and totally independent of any opinion, positive or negative, regarding the subject of the letter. Having stated for the record what should be obvious, I will now present the considerations themselves.

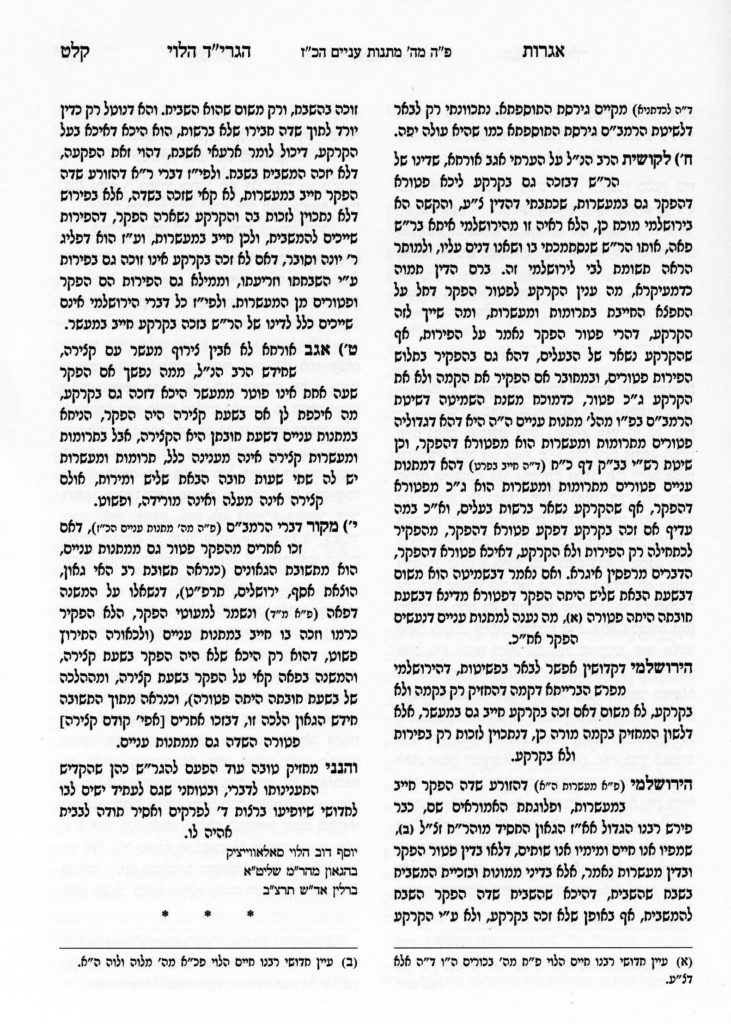

1. First, and this alone should suffice, is the error in the spelling of the name. The Rav spelled his name דוב with a vav in the middle and not דב without a vav. I have never seen a signature of the Rav without the vav and I challenge all of those who doubted our claim to produce a signature of the Rav, in his handwriting, without a vav. As there are a multitude of “semikhah klafim” signed by the Rav, as well as numerous letters that he wrote, I assume that this can be readily verified. I would add that, unlike dates or plain text, it is rare indeed that people make typos in their signature.

2. The Rav’s signature in the letter contains an additional conclusive indication that the Rav didn’t write it which is the mention of his father and his title. The Rav would use the title אבא מרי when referring to his father in his halakhic writings and famously utilized it in the title of a major work, Shiurim le-Zekher Abba Mari (Jerusalem: Mosad ha-Rav Kook, 1984). However, he never used it when referring to his father, Reb Moshe Soloveichik, in his signature. Usually, the Rav signed his name without mentioning his father but if he did mention him, he always used the Brisker title of הגאון החסיד or variations of it and never אבא מרי. Thus, he might sign בן הגאון החסיד or בהגאון מהר”מ – see Iggerot ha-Grid pp. 139-140 for two such examples – but not אבא מרי as in the letter under discussion.

The vast majority of the letters that I have had occasion to see, as well as those published in *Community, Covenant And Commitment: Selected Letters And Communications*, ed. Nathaniel Helfgot (Jersey City, NJ: Ktav, 2005), and originally written in Hebrew, contain the Rav’s name alone without any reference to his father whatsoever. Moreover, my impression is that the younger the Rav was and the more “rabbinic” and traditional or ceremonial the context (such as HaPardes), he might refer to his father, while in more political or non-rabbinic settings and the older he gets, he rarely signs as his father’s son. This is doubly true of the years when he had physical trouble writing (for examples of 2 late letters in very rabbinic settings in which his father is not referenced in his signature, see the letter published in the beginning of the first volume of the first edition of the Shiurim le-Zekher Abba Mari and/or the letter written to Rabbi Shemariah Gourary in October 1978 and published in a Chabad journal upon his petirah in 1993).

The bottom line is that the vast majority of all his letters don’t mention his father and this is esp. true in the later years. Thus, the very reference to his father in a very late letter to a secular political figure like Chaim Herzog might already raise suspicions about this letter, but the crucial point is that even when mentioning Rabbi Moshe Soloveichik, he is never referred to as אבא מרי. Presumably, the person who wrote this letter was aware of the Abba Mari title because of the book (which had just been published a year earlier), but unfamiliar with the Rav’s normal signature mode and thus blundered into applying the wrong title to Rabbi Moshe Soloveichik.

In an aside, I’ll also mention that the person who wrote this letter was not only woefully unequipped with knowledge of the Rav’s signature, he also didn’t know how to spell אבא מרי properly. Unlike the Rav, who was aware of the phrase’s origin in the Shas (Kiddushin 31b and Sanhedrin 5a) and its usage by the Rambam in Mishneh Torah (Hilkhot Talmud Torah 4:3 and Hilkhot Shehitah 11:10) to refer to his father and, of course, spells it properly, the writer of this letter can’t even spell the title that he chose properly (although I can’t rule out the possibility of a typo, I cannot but have the impression that this is yet another instance of the work of someone who simply doesn’t know what he’s doing).

3. The letter includes the title איש בוסטון together with the signature. I’d love to see another letter of the Rav in which he signed himself as איש בוסטון. Until such a letter is produced, I regard this as an additional example of the fraudulent nature of this letter since the Rav didn’t use such a title to identify himself. He was not Paul Revere and apparently did not consider איש בוסטון to be a defining characteristic.

4. A crucial element in assessing a signature’s authenticity a graphological examination. In our case, the signature of the Rav in the Herzog letter simply fails the most basic graphological test. Since a graphological analysis is by definition subjective, I preferred to present the verifiable objective evidence regarding the Rav’s signature prior to raising this point. I also feel obligated to preface my claim with two preliminary comments about the legitimacy of handwriting comparisons:

a. Halakhah and the American banking system that has utilized handwritten checks for decades as a prime form of payment rely upon comparison and recognition of an individual’s signature. The concept of kiyum shtarot, a major legal mechanism in Halakhah which is crucial to all legal documents, is predicated upon comparing signatures.

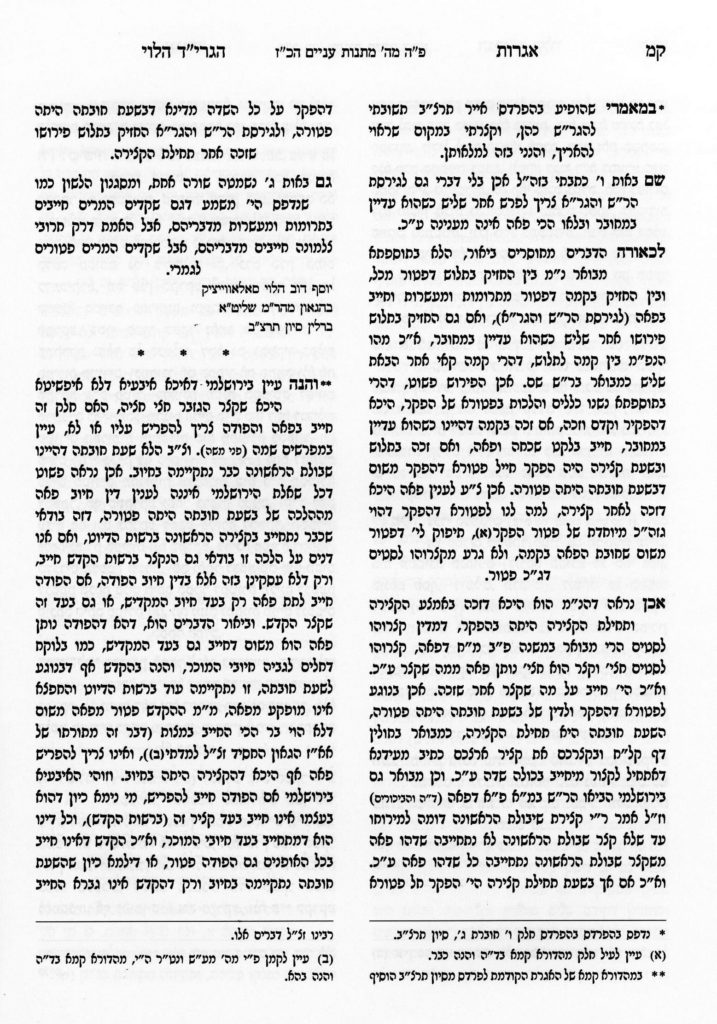

b. The Rav’s signature is quite distinctive and remained consistent throughout the years. A clear line runs between all his signatures, from youth to old age. In his later years, the signature is more frail and less forceful than his earlier signatures, but the basic form is constant and readily recognizable. The signature that appears in the Herzog letter is so starkly different from his recognized signature that this is a plain case of black and white and not a grey area. Had it been a grey area which required a judgement call, I would never make such a subjective claim, but the contrast here is so great that it does not require a judgement call. To utilize a Talmudic concept from a somewhat different case of graphological assessment, an average ינוקא דלא חכים ולא טפש could easily make this call.

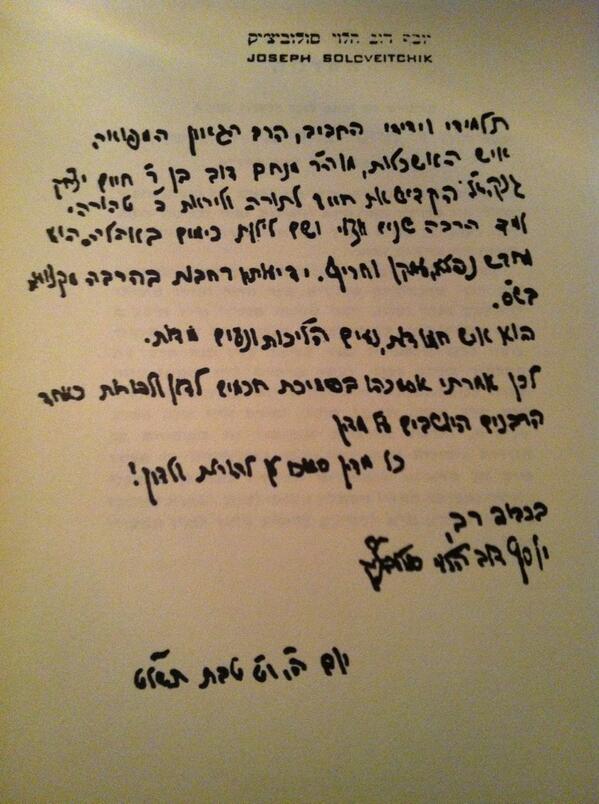

To back up this claim, I suggest that the interested reader see for himself examples of the Rav’s signature in these years. An example from June 1983 is the letter printed in the first volume of Shiurim le-Zekher Abba Mari (first edition).

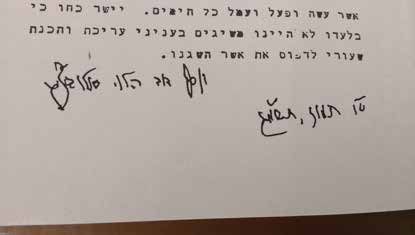

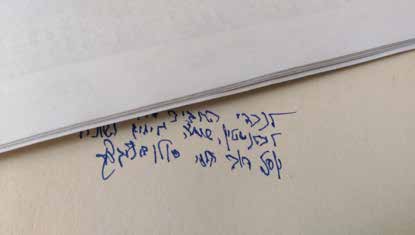

A later example, and even more relevant example, from Winter 1984 (probably January-February 1984) is this (from a dedication he inscribed to me in the Shiurim le-Zekher Abba Mari that he sent me):

One can notice 2 things in this signature: 1. Its basic consistency with his younger signatures 2. the frailty of his writing. The signature in the letter to President Herzog, in contrast, is inconsistent with all of the Rav’s signatures and does not express the frailty of his aging motoric skills, despite supposedly being written months later.

For a somewhat earlier, albeit still late, example, one can see the signature in the haskamah published by Rabbi Menachem Genack in his sefer ברכת יצחק, written in Jan. 1979.

In summary, the signature itself in the document under question is so full of errors that if it were a get, you could say that it contains almost all possible פסולים as it includes א. שינה שמו ב. ושם אביו ג. ושם עירו ד. ואינו מקויים .

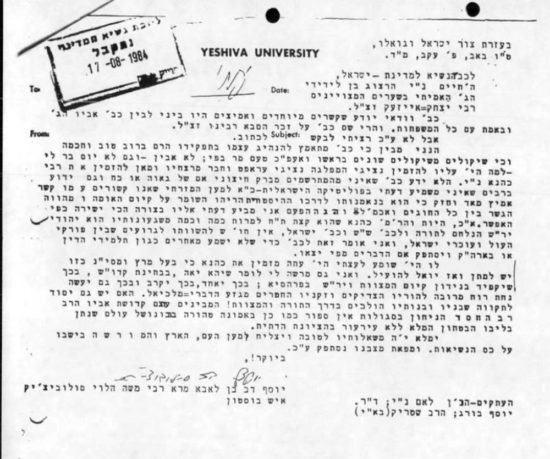

From the signature, let us turn our attention to the stationery. Anyone who has seen letters of the Rav knows that the letterhead is always the Rav’s name and usually, but not always, his address as well. He does not use Yeshiva University stationery nor RIETS stationery. I have never seen a letter written by the Rav on a YU letterhead. He was not the Rosh Yeshiva of RIETS or president of YU – he was Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, the Rav, and his stationery reflects this.

It must also be emphasized that this particular letter is purported to have been written in Boston where the chance that the Rav used YU stationaey is nil. I was with the Rav in Boston during the summer of 1984 and I can attest to the fact that he did not have YU stationery in his study that summer (nor at any other time that I was in Boston).

Thus, it seems fairly obvious to assume, although I cannot verify this, that ‘the writer of this letter’ had access to YU stationery which is dispensed to hundreds of locations but not to the Rav’s private stationery and, therefore, chose to present the Rav as writing on YU stationery, unaware that by doing so ‘he’ is undermining rather than bolstering the credibility of his forgery.

Actually, what ‘the writer of this letter’ is doing is even more bumbling since ‘he’ is not using proper YU letterhead stationery either; if one looks carefully at the letter that was reproduced at the Seforim Blog, it can be noticed that it is written on paper designed for internal correspondence as a memo and is not formal institutional stationery of the sort that is appropriate to use in correspondence with a head of state.

Another suspicious element is the copies of the letter that supposedly were sent to Rabbi Norman Lamm, Dr. Burg and Rabbi Michael Strick. Aside from the fact that to the best of my knowledge, it was not the Rav’s custom to copy others on his letters and this alone is room for additional suspicion, it is unfathomable to think that he would have Rabbi Strick’s name as one of those copied to his letter. Was the Rav even aware that Rabbi Strick worked in YU’s Israel office? Even if so, why would he copy him on a letter to Herzog which does not deal with YU affairs? For that matter, why would he copy Rabbi Lamm?

Since the Rav did not ‘CC’ people and was unaware of Rabbi Strick’s position, this, too, is an additional reason that at least parts of this letter must be considered inauthentic and the work of others. [If one were to argue that this anomaly is reason to support the letter’s authenticity as a lectio difficilior, I would counter that such an argument would be reasonable, if it could be established that the Rav was aware of Rabbi Strick’s role in YU Israel, but since this is definitely not the case, he couldn’t have copied on a letter someone who he was unaware of his position. Thus it is not a more difficult reading, but rather an impossible one and, therefore, proves its inauthenticity rather than its authenticity.]

Next, let us turn our gaze to the top of the page and the salutation of בעזרת צור ישראל וגואלו. Once more, I challenge anybody to produce a letter or document in which the Rav used such a phrase to refer to the KBH in a similar context (or any context, for that matter).

Although one could conceivably argue that he did not normally do so but changed his custom when writing to the president of Medinat Yisrael, I would not accept such a line of reasoning because of the reasons outlined below, but I would also emphasize that the Rav’s letter to Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion does not contain such a phrase nor do any of his other letters to various Israeli Religious Zionist leaders. All of these letters were published in *Community, Covenant And Commitment: Selected Letters And Communications* and are readily available for examination. If one were to argue more ingeniously that he used the phrase only in a letter to Chaim Herzog because of his father, Rav Yitzhak Isaac ha-Levi Herzog’s involvement in the formulation of Tefillah Leshalom Hamedinah, he would have not only to claim that the Rav was attempting to compliment Herzog but also to establish that the Rav was aware of Rav Herzog’s role in the formulation of that text. Personally, I am quite skeptical of this for a variety of reasons, but I will not insist upon it in this discussion.

The crucial point regarding the use of צור ישראל וגואלו is that the Rav would never use such a phrase. Without entering into a protracted discussion of the Rav’s attitude to Zionism in general, a topic that much has been written upon, I will allow myself to state that while undoubtedly supportive of Religious Zionism, he was deeply opposed to three elements of Israeli Religious Zionism that he encountered in his contacts with the Israeli Religious Zionist sector. The first was the ideological position that Jewish Nationalism and its political expression are of the highest religious value. The second, not entirely unrelated to the first, was the perspective that viewed the establishment of the State of Israel and its subsequent achievements as highly significant stages in the Redemption. Regarding those who held to a position that he described as the attachment of “excessive value to the point of its glorification and deification” [of the State of Israel] (*Community, Covenant And Commitment: Selected Letters And Communications*, page 164), he defined them as delusional (the original Hebrew uses the phrase “הוזים” which is translated in the published text as “dreamers,” but which actually has a much stronger connation of delusion within it) and in total error. He was also very distant from a historical appraisal that saw the Geulah as imminent. As anyone who has read *Kol Dodi Dofek* or *Hamesh Derashot* is well aware, the Rav emphasizes the Man-God relationship in the context of Zionist history rather than the imminent realization of the promised Redemption.

An additional element that the Rav strenuously objected to was various expressions and formulas in liturgical or halakhic settings that were disconnected from traditional forms of expression and exuded a strong sense of a break with the past and the creation of a new religious language. I would not overstate the case if I stated that such expressions actually caused him to cringe. He certainly was emotionally distant from such phrases and did not use them. A famous example of this was his insistence upon the term “Eretz Yisroel” rather than “Israel,” but there were many such examples, some better known (e.g. translating the text of the ketuba into Hebrew), some not so well known. Even wearing a white shirt on Shabbos (“Israeli style”), rather than a suit, would sometimes annoy him if he sensed that it was an expression of non-traditionalism and “anti-Galut” sentiment. I can attest to this first hand כי מבשרי אחזה זאת. I spent time with my grandfather, the Rav, as a wide-eyed 17 year old youth who often expressed his Zionist sentiments in front of him and occasionally raised his ire by doing so. Once, discussing a related topic, he admitted to me that reciting a certain text was rationally the proper thing to do, but, nevertheless, expressed a personal emotional reluctance to do so because of its novelty and lack of traditional moorings.

Therefore, although this is admittedly a subjective criterion that I am attempting to avoid, I cannot believe that any letter that the Rav wrote or authorized – even to a head of state whose father was Rav Herzog – would contain the phrase בעזרת צור ישראל וגואלו.

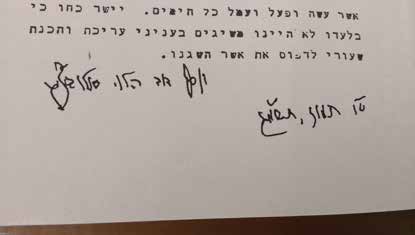

Finally, I must point out an issue of content regarding the letter. As I stated at the outset, I am not judging the letter based upon any presumed attitude of the Rav regarding Rabbi Meir Kahane. However, the content of the letter is extremely problematic for totally other reasons. As can be seen, the letter concludes with a clear admonition and rebuke to President Herzog in no uncertain terms regarding his level of observance. Not only does the writer allow himself to criticize Herzog’s standards of public observance, an obviously sensitive topic for someone raised as an observant Jew, he also doesn’t shy away from introducing the extremely sensitive and intensely personal issue of Herzog’s relationships with his parents and children in light of his problematic observance of Mizvoth.

I will allow myself to state that the Rav that I knew, and I assume many of the Seforim Blog’s readers as well, would never enter into such personal matters and grant unsolicited advice and judgement upon his correspondent’s personal life and relationships. For that matter, I cannot imagine that any rational individual who is requesting a favor from a person of stature would conclude his message by rebuking the person and making it clear that he is a disappointment to his parents. Why the writer of this letter thought that this is a reasonable text is beyond me, but if he chose to concoct such a text, I do claim that the Rav would not, and could not, have written such a text. While this is admittedly subjective and, therefore, I do not rest my case upon it but rely upon the above-mentioned considerations, I do believe that the Seforim Blog’s readers should be alerted to this perspective as well.

I will not continue to discuss this letter, although much more could be said about it. In conclusion, I will add that I believe that many of the points that I raised above suffice to individually prove that this letter is utterly false; however, it is also important to emphasize that there is a significance to their cumulative effect. Thus, even if one can argue or suggest alternatives to a particular claim, the accumulation of so many suspicious characteristics is an additional consideration to recognize that the text is much too problematic to be trusted or relied upon.

Ironically, whoever thought to send this letter to President Herzog and to appeal to his zekhut avot as part of a letter requesting support for Rabbi Kahane was probably barking up the wrong tree by doing so. Rav Yitzchak Isaac ha-Levi Herzog, whose authority is celebrated in the letter, had the following to say about the issue of retribution and Jewish-Arab relationships in times of terror attacks, published on the front page of the newspaper Davar, Friday, July 8, 1938, and translated into English several months later in Contemporary Jewish Record 1:1 (September 1938):

Why did someone want to counterfeit a letter in the Rav’s name is a question that may be unanswerable, even if we were to identify the person who wrote the letter. It is certainly unanswerable without identifying the writer. It should be recognized, though, that the primary motivation may not have been a political agenda to validate Rabbi Kahane, although it is obvious that the writer’s opinion of him is somewhat favorable and that he is attempting to advance the Kach party’s agenda, but may be rooted in other realms. For instance, the writer may have had a psychological need to empower himself to speak as the Rav, for a variety of reasons, and realized this by counterfeiting a letter in the Rav’s name and sending it to a prominent and famous person.

Whatever the motivation may be – political or psychological – we must recognize that this is a letter that that was not signed or authorized by the Rav and that is what matters.